An advertisement for a theatre production about urban Affichistes inspired this image of two Affichistes who walk the streets decorating walls with strips of tattered manifestos, creating beautiful works of art that are urban and non-conforming. The city lives off all the new ideas that emerge from these moments, ideas that often completely upset the logical sense of the things. The idea of the Affichiste has existed since the 1960s, when a group of artists calling themselves Affichistes emerged in France, Germany, and Italy. Their principal exponents were Jacques Villeglè, Raymond Hains and Mimmo Rotella.

Il manifesto di un opera teatrale sugli attacchinatori di manifesti, ha fatto nascere l'idea che tali due individui andassero ad attacchinare pezzi strappati di manifesti creando splendide opere d’arte dal gusto urbano e non conforme. La città vive di tutte le idee nuove che ogni giorno nascono al suo interno e spesso tali idee finiscono per stravolgere totalmente il senso delle cose. E' storicamente esistita dagli anni sessanta una corrente artistica chiamata "Affichistes" tra Francia, Germania e Italia i quali esponenti principali sono stati Jacques Villeglè, Raymond Hains e Mimmo Rotella.

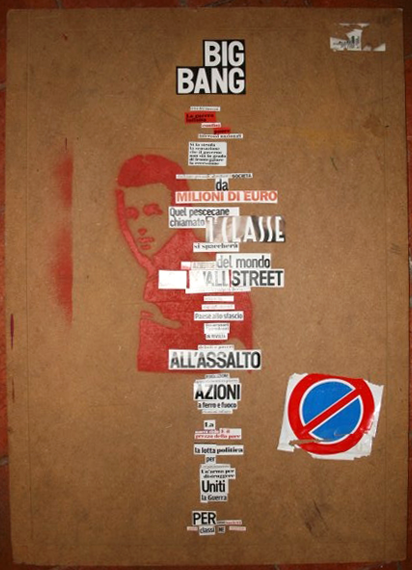

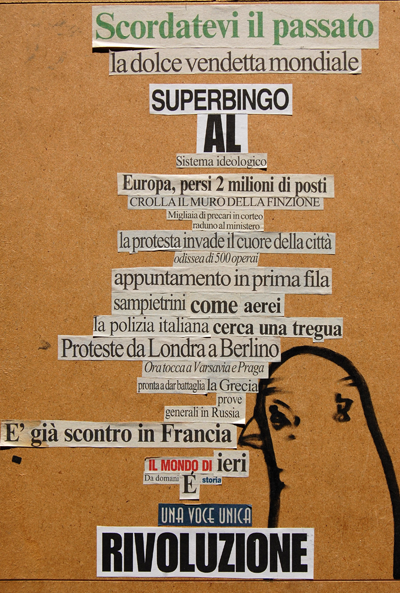

This artwork is realised on a piece of plywood using the collage technique. It is incredible how one single sheet of newspaper can – almost casually – make sense of so many different concepts like civil war, revolution, demonstration, politics, money, corruption, poverty and so forth. All these terms adjusted in their consequential and temporal dispositions give a very different view on the stories the media tells, making it possible to extract interesting scenarios of rebellion, of organisation and protest, as well as revolutionary outbreaks from liberal democracy. Let’s not forget that we would have every reason to do this in our own contexts as well.

Quest'opera è statarealizzata con la tecnica del collage su una lastra di compensato. E' incredibile come un solo giornale quotidiano, preso a caso, contenga tanti termini come, guerra civile, rivoluzione, manifestazioni, politica, soldi, corruzione, povertà, etc. Tutti questi termini, ordinati secondo la loro giusta disposizione temporale danno una visione molto diversa da quella proposta dai media, si può in tal modo estrarne interessanti scenari di ribellione, di organizzazione politica e di piazza, come anche di travisamento rivoluzionario della democrazia. Ricordiamoci che avremmo tutte le buone ragioni dalla nostra per agire in tal modo all'interno del nostrocontesto sociale e politico.

Here, coloured strips of manifestos are applied to an old commercial billboard poster. The lines of the manifestos enable the colours to converge into geometrical figures, mostly cubes. This creates a kind of minimalist landscape that the woman on the left-hand side seems to be claiming for herself in her appreciation of the street art.

Per questa immagine è stato utilizzato un vecchio cartellone pubblicitario unito a strappi di manifesti lacerati. I colori e le linee riconoscibili su ciò che resta del manifesto vengono fatte convergere in modo da creare figure geometriche, cubi in particolare, formando un panorama minimalista che la donna sembra reclamare, con uno sguardo di simpatia per l'arte di strada.

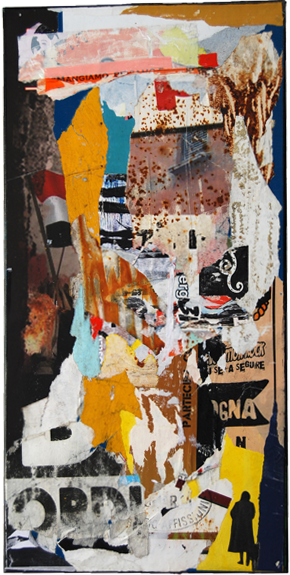

This work is realised on canvas with the remains of tattered manifestos that have been molten together with glue. The strips of paper are from walls in Bologna and Florence. The piece reveals the elements that determine its structure – the composition of the paper strips and the colours that are used provide the balance between colours and images. Anyone can see whatever they want to in this image. Yet, what is interesting is that it is possible to find so much stuff on the walls and in the streets that can be used for art without having to spend a penny. One can simply reuse materials that others have discarded as junk. In this case, instead of putting something into the street, you take from the street the materials with which you then give back to society in the form of art.

Questa opera e stata realizzata su tela con soli strappi di manifesti poi incollati tra di loro. I manifesti provengono dai muri delle città di Bologna e Firenze. Ognuno in quest'immagine può vedere cosa desidera anche se sono presenti alcuni elementi che ne determinano la struttura. Gli strappi di manifesti non sono messi a caso, sono il risultato del bilanciamento tra colori eimmagini. La cosa interessante però è che si può recuperare dalla strada molto materiale per la creazione artistica senza spendere un penny, riutilizzando qualcosa che gli altri reputavano spazzatura o degrado. In questo caso al posto di mettere nella strada, ad esempio pitturando su un muro di dominio pubblico, si prende dalla strada per ridarlo alla società in forma di arte.

RESPONSE BY

Begüm Özden Firat

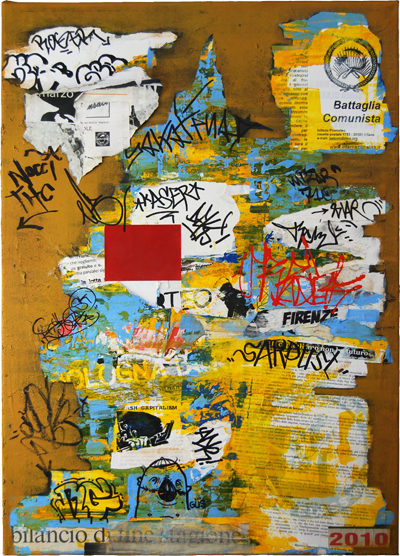

This piece is realised on canvas with a background of manifestos and political flyers covered with applications of clear blue and yellow colour, as well as tags by several graffiti artists. It was created with a street near the University in the centre of Florence (Italy) in mind, where the walls are painted on by street artists, where commentary on the most recent political issues and 'the movement' are sprayed on the walls and manifestos are fly-posted by the different political persuasions in a war against hostile authorities that spend their time ripping off manifestos and covering up the texts and paintings. In this picture, the colour wins back space from behind the monochromatic 'white-washing' of the authorities, so that the manifestos can appear once again.

Questo pezzo é realizzato su tela con sfondo di manifesti e volantini politici poi elaboraticon applicazioni di colore azzurro e giallo. In seguito sono state apposte firme di "Writers" dagli stessi. E' stato creato pensando a una delle strade del centro di Firenze vicino all'università. Là vengono fatte scritte a bomboletta sui più recenti fatti del movimento e della politica, affissi manifesti di tutti gli schieramenti politici e studenteschi e pitturati i muri dagli "Street Artists" in una guerra con le autorità che ostinate continuano a cancellare e ripulire quei muri. In questa immagine il colore torma a farsi spazio da dietro le cancellature facendo riemergere scritte e manifesti.

The composition reads: BIG BANG / market crisis / infinite war / borders / fears / national interests / the feeling that the government is not able to face the recession advances / Individuals are at risk in the same way as firms worth millions of Euros / that shark called the 'upper class' will break apart / the corporations of the world fall with Wall Street as the stock exchange strikes / liquidity crisis / wage freeze / country in ruin / revolting employees / the weak and the poor/ attacking/ revolution / square meetings / actions / fire and sword / endless meetings / civil war/ is the price of peace / political struggle for organisation / the weapon to destroy / united / the war / for a classless and borderless society.

La composizione recita: BIG BANG / Crisi dei mercati / La guerra infinita / Confini / Paure / Interessi nazionali / Si fa strada la sensazione che il governo non sia in grado di fronteggiare la recessione / Rischiano privati /e altrettanto / Società da / millioni di euro / Quel pescecane chiamat / 1° Classe / si spaccherà / Le / Aziende / del mondo / con / Wall / Street / cadono sotto i colpi di Borsa / Crisi di liquidità / Stop ai salari / Paese allo sfascio/ Lavoratori dipendenti/ in rivolta/ Deboli e poveri / all’assalto Rivoluzione / Appuntamenti in piazza/ Azioni/ a ferro e fuoco/ Riunioni infinite / La guerra / civile / E'il prezzo della pace / La lotta/ politica per l'organizzazione un' arma per distruggere Uniti / la guerra Per / una / società / senza / classi / né / frontiere.

COMMENTARY

Gavin Grindon - Visual and Material Culture - Kingston University

Though this first 'intervention' (though it is more an extraction) evokes the busy space of the street only to move it onto canvas, its approach is quite distinct both from the mid-century affichiste aesthetic of Dufrêne, Hains or Villeglé, and from the common street-art aesthetics that echo them. They had ripped posters from walls to create a 'new realist' aesthetic of spatial collage which rearranged strips of barely-legible fragments of everyday life, placing the vitality of these quickly torn strips and the competing bold designs and bright colours of different advertisements on the inside walls of the gallery. But despite its ambiguities, this aesthetic, reiterated by street artists across gentrifying neighbourhoods from Brooklyn to Hackney, has come to evoke not a simple 'new' urban vitality but a spectatorial and ‘autonomous’ (and, inevitably, speculative and opportunist) attitude to urban poverty and material decay as 'picturesque.' Their new realism long since absorbed by what Fisher (2010) has termed a 'capitalist realism.'

Elsewhere, Dellatonio evokes this historical movement in playful terms with a neo-affichiste montage. In two pieces, the aesthetic of affichisme is used not as an intervention into the matter and materiality of urban printmaking, but as a signifier of a particular artistic practice, within a larger montage that constructs a narrative around it. In one, against a bright blue sky background, a female figure from what seems a rather dated advertisement shouts cheerfully, in what in this context seems a Western commodified and domestic response to Rodchenko’s famous 1924 publishing house advertisement depicting Lilya Brik shouting. But now rather than advertising revolutionary textbooks, or washing powder, her shouted bubble caption, "now even better!" doesn’t interpellate us as consumer or revolutionary subject but ironically leads our eye only to a an indiscernable rough, angry affichiste mess of torn colours which jar with this bright cheerful scene. Rather than a sincere announcement of an unproblematic renewed affichiste vitalism, it seems a brute statement of impossibility. Elsewhere, the point is pressed home, as a poster advertising a theatre production about two street artists finds itself placed on a canvas, but now the extradiagetic visual play of the original poster - which depicts the fictional pair putting up a poster which actually advertises the show they are in - is undone. They and their poster-brush extending across the piece remain intact, but the poster they are putting up is impossibly already torn and layered by other posters before it is even affixed. And while this affichiste signifier sits within this image below it to create a new playful narrative meaning, it also begins to break outside of the top edges of the frame of this original image, asserting itself as the dominant outer conceptual frame. In each case these more narrative constructions assert the historical distance between this aesthetic and its present uses.

Returning to the first image, it is now not affichistes or competing advertisers, but council employees - who do not rip the posters or replace them with other bigger posters, but simply paint over this heteroglossic space in monochrome blocks of colour, a simple closure of debate and representation which echoes the close control of the media in Berlusconi’s Italy. Dellantonio's move from political flyers and street-posters to canvas doesn’t invoke 'the street' in celebratory fashion as an abstract ideal of political participation, as it often has been for artists and writers since '68, but indicates a specific, historical space, a street near the university in Florence used for wheatpasting popular political posters, flyers and announcements, often graffiti’d with critical or supportive responses. This specificity manifests itself not only in the minimal pictorial content, but in the large areas of detailed text left visible. In her essay, 'concrete needs no metaphor,' Feigenbaum (2010: 120) argues that fences, so often turned into makeshift collective canvases in protest situations, do not function simply as a pictorial or discursive surface, however heteroglossic. Instead, these surfaces affect the bodies of those who write, paste or attach things to them, in a moment of 'communicative struggle.' Such moments of struggle are micropolitical, often invisible. Dellantonio's piece recalls public space in these terms, not the street as ideal public sphere or open democratic space so much as a marginal and ephemeral location of struggle, in which the authorities simply remove or bluntly paint out heteroglossic debate. In the next piece in the series, this process is evoked in more tragic terms. The canvas is composed of fragments of manifestos pasted in the streets of Bologna and Florence, but torn and reposted without text, as abstract shapes and colours, or fragments of images, no longer legible as anything but vague impressions, and smeared and spattered with rust or mud. Political participation here - in close attention to the wall - is not heroic but contingent, vulnerable and ephemeral. In the first piece, the informal frame of rough oblong squares of colour impinging on the text suggest casual brushstrokes, as if what we can read is momentarily to be swallowed by the next movement of the brush wielded by a council employee. Or, perhaps now finding itself on canvas in the more reflective, and fantastical, institutional space of art, we might imagine an alternative movement in which, spectre-like, the claims, hopes and promises of the movement have pushed their way through repression into visibility. While evoking this moment in which the materials of social movements come to haunt public space and are extinguished, the canvas itself functions as an echo of or memorial to this moment of posters and flyers on this wall, both specific and local yet common to the experience and growth processes of movements across the urban West.

In two other pieces, Dellantonio presents a similarly fantastical visual act of sabotage, in which the text of a newspaper is cut up and rearranged into a poetic ransom note which releases the submerged histories held captive within the reductive hegemonic narratives of the mass press, through which protest and social movement action events are normally represented. The same words burst forth in a new order, a return of the repressed in a fantasy of revolutionary organisation, "that shark called first class will break apart/ the companies of the world with wall street fall at the strikes of the stock exchange... the weak and the poor/ attacking / revolution/ square meetings / actions/ fire and sword / endless meetings / civil war / is the price of peace."

Across these pieces, there is a focus on submerged narratives of organisation, on the work and relations whose material traces are lost soon after the event, left in barely-visible fragments either on the repainted walls or buried in the simplified repetitive narratives of the mass media. What is really interesting here is that this approach suggests a more intimate reflection than the most common representational strategies used in figuring social movement. In the first image, finally, there is no heroic moment of visibility, the street pictured as filled by a massed crowd pictured from an elevated height. Instead, there is text without people, and a focus on the small, hand-held materials of movements, in an earlier and usually far-less visible moment of invocation and organisation.

Feigenbaum, A. (2010): 'Concrete Needs No Metaphor: Globalized Fences as Sites of Political Struggle,' Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organisation, 10:2, pp.119-133.

Fisher, M. (2012): Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? London: Zero Books, 2012.

top

Begüm Özden Firat - Sociology - Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul

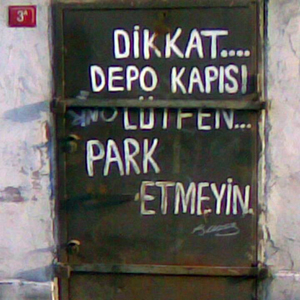

The writing on the building number 3A reads: "BEWARE...STORAGE DOOR PLEASE...DO NOT PARK."

It is quite common in cities across Turkey for ordinary people to write such statements on the walls of buildings. By doing so, they communicate their requests, wishes, and sometimes their anger. What makes this one distinctive is the signature of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, sprayed below the text by an another anonymous passerby. One can run into Ataturk's signature in different urban settings – schools, monuments, or hospitals – adorning his countless aphorisms which usually glorify the Turkish nation. Yet, never in the form of what we can call an 'urban intervention'. Here, I am not going to delve into a discussion of how acts of detournement, such as this one, gain political significance.

What interests me in this image in relation to Alexander Dellantonio's Urban Interventions series is that it clearly demonstrates that shared urban walls produce a sense of publicness through continuous acts of collage and decollage. Walls are contested and negotiated spaces of encounter where people communicate with each other – from their intimate feelings to agitational revolutionary slogans. This is why the powers that be want to take total control of urban space through the implementation of laws and regulations and the development of techniques and technologies designed to shorten the life of such interventionist practices. After all, public space should be planned and regulated, and it should be orderly and safe.

Political and social movements must continually claim their presence in public space, if they ever are to be seen and heard. One of the main aims of dissident movements is to occupy public space and retrieve it from the Colonisation of capital and political authorities so as make it an open space for all. In this quest for emancipation, walls appear to be one of the sites of struggle where the confrontation takes the form of graffiti, stencils, stickers, murals, posters and the like. Yet, such inscriptions are always tainted by ephemerality. In order to counter their transient existence, activists deploy different tactics.

There is an almost forgotten tactic in the long history of flyposting. You break a couple of light bulbs, mix them with glue and then plaster your posters wherever you want them. Broken light bulbs make it difficult to remove the posters. The hope is that this practice can also deter the authorities from removing the posters. It seems like the new generation of activists and street artists have developed different strategies for prolonging their interventions, such as using durable chemicals as well as documenting them by taking photographs. The Urban Interventions series can be seen as yet another way of making street art endure.

The Urban Interventions series consist of collages of urban word- and image-scapes (posters, graffiti tags, newspapers, advertisements). The desire is to preserve the ephemeral by fixing whatever remains from the street on a manageable surface. We can read this act of preservation as a humble attempt to make sense of street politics and poetics, archiving the traces of what was once there. However, it seems to me that this urge to capture the potentially passing in such a manner misses the very politics of the street: a politics based on a constant struggle that produces alternative and unanticipated meanings. The writing on the building adorned with the signature of Ataturk is a good case in point for such struggles, where the concerns of the common clash with those of a public taboo. The everyday world confronts the official world and opens up a third level of understanding that offers an estranged vision of both of them. This clash between heterogeneous elements (and violently separated worlds-of life and arts, aesthetics and commodities) is indeed the basic tenet of the aesthetics and politics of the collage - from Braque to Dada all the way to the works of Martha Rossler and Barbara Kruger. In such works, a dialectic between the heterogeneous parts opens up the space of the 'interval', which is the realm of shock and provocation, and of thought. In Urban Interventions, it seems rather like the collage form produces a homogenous and cohesive unity between the assembled pieces (tags, manifestos, leaflets, newspaper cuttings and advertisements). The pieces suspend the act of confrontation so dear to the politics of collage in favour of representing the dissident's voice and visuality. Theodor Adorno once criticized 'committed art' for bleating what everyone is already saying or at least secretly wants to hear. This is why, for him, such art runs the risk of becoming an empty slogan and preaching the converted. In a similar vein, when we see the manifesto with the title "battaglia communista" for example, our hearts may move a little faster, but it does not necessarily provoke us to think or act.

One must admit that there is something politically motivating about the Urban Interventions series, as it brings together bits and pieces of 'signs' of comrades in other parts of the world. It makes you feel like the movement is indeed everywhere. Yet, the series also shows us that we should try to find ways of making sense of our struggles beyond the limits of representation. Experimenting with creative ways of fabricating antagonisms on canvases is as revolutionary as producing them in the streets.