“I can sell my body if I wanna,” shamelessly snarled Kathleen Hanna, front woman of the 1990s feminist punk band Bikini Kill and cofounder of the riot grrrl movement, in the song “Jigsaw Youth.” A movement intentionally vague so as to be inclusive, riot grrrl’s impetus was to combat patriarchy and to empower young women to connect with one another and take up space in unprecedented ways, in the punk scene and in the world. The band that aimed to create a participatory feminist youth culture that would change society1 and the grassroots movement that it was a part of used consciousness raising, creative resistance, and cultural production to realize its goals. While specific methods varied, reflecting both a political commitment to fluidity and plurality and the neoliberal ideology of individualism and “personal responsibility,” the performance of shamelessness underscored this movement of feminist resistance.

Many of riot grrrl’s methods have been polemical. On one hand, “riot grrrls foreground girl identity, in its simultaneous audacity and awkwardness—and not just girl, but a defiant ‘grrrl’ identity that roars back at the dominant culture.”2 Defying the male gaze by shamelessly embracing sexuality was a form of self-definition appropriate to a movement that viewed sociocultural reappropriation, personal transgression, and personal transformation as revolutionary (which the name “riot grrrl” suggests). On the other hand, reappropriating the norms of femininity was a fraught process that was delimited by white middle-class privilege, and the focus on individual transformation reflected a neoliberal framing of the failure to take “personal responsibility” as the cause of inequality, oppression, and violence. Leaving the structural sources of inequality, oppression, and violence intact, this reduces transformation to an individualized project. Riot grrrl was also criticized for perpetuating patriarchal objectification by embracing sexuality in some conventional ways, such as through stripping and other forms of sex work.

Riot grrrl also galvanized young women, evident in interviews with and in the cultural productions of its members, the increasing prevalence and variety of female musicians, girls’ rock camps, the proliferation of academic and popular writing on riot grrrl, and ongoing feminist activism on the ground, in the academy, and online. Hanna has also had success with her subsequent bands Le Tigre and The Julie Ruin, and was recently immortalized in 2013 biopic The Punk Singer. The place of riot grrrl in US feminisms is unequivocal, and today its legacy (and prevalence in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies syllabi) connects new generations to the movement and continues to influence and inspire its veterans. At the time of writing, searching the George Mason University library database for “riot grrrl” produced 743 hits; entering it into Google produced 1,030,000 and there are numerous extant riot grrrl or riot grrrl-inspired groups throughout the world. One could hardly say that (the initial) riot grrrl movement did not have some salutary impact on the lives of many young women.

This essay has three goals. First, by focusing on word reclamation via body writing, it examines how riot grrrl attempted to utilize the performance of shamelessness—that is, the performance of alternative forms of young female value—to resist patriarchy and the brutalities of neoliberal capitalism. Second, it shows how riot grrrl performances—on stage, in other cultural production, and in the daily lives of young women—also inadvertently embraced neoliberal tropes. I argue that while riot grrrl performances of shamelessness resisted the gendered politics of respectability, they did so in a way that was not accessible to women of color, who historically have been already cast as hypersexual and sexually deviant; women of color did not have the same binary between being respectable or disrespectable. In failing to consider how women of color have been shamed as hypersexual and sexually deviant, these practices recuperated white privilege and class privilege in ways that are characteristically neoliberal. In other words, in eschewing white privilege and also middle class privilege—specifically in relation to individualized/individuals’ performances of shamelessness via body writing—riot grrrls supported (or at least failed to undermine) neoliberal hegemony.

At the same time, understanding media and performance as polysemous sites where there is an ongoing negotiation of meaning between institutions, texts, and audiences,3 and in the spirit of riot grrrl, I am interested in the productive potential (if any) of performing shamelessness. Thus, finally, this essay is a call to action or at least a call for a discussion around the perils and possibilities of shamelessness. Is performing shamelessness an untenable form of feminist resistance? Are there ways that shamelessness can be revised or reconstituted to be truly accessible, and thus to effectively roar back at racism, patriarchy, and neoliberalism?

Why Shame/lessness, Why Then?

Shame as a prevalent manifestation of the brutalities of neoliberal patriarchy galvanized young women in the 1990s; in accordance with Foucault’s assertion that power creates and shapes resistance to it, shamelessness was a key method of resistance utilized by riot grrrls. While adolescent women, simultaneously dismissed as children and sexualized as women, have long been disciplined by discourses and practices of shaming, the punk movements and women’s movements of the 1970s and the neoliberal conjuncture of the late 1980s and early 1990s set the stage for riot grrrl’s emergence, and the movement’s deployment of shamelessness. Given that my focus is on body writing/word reclamation particularly as performed by Hanna, I cannot do justice to these rich, nuanced movements here. The following gives just a sense of the contours of punk and earlier feminisms.

Punk, a series of movements that emerged in the 1970s, is described by Kevin Dunn and May Summer Farnsworth as, “a major disruptive force within both the established music scene and the larger capitalist societies of the industrial West. Punk was generally characterized by its anti-status quo disposition, a pronounced do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, and a desire for disalienation (resistance to the multiple forms of alienation in modern society).4 Punk, which included independent cultural production including often loud, aggressive music, art, writing, and fashion, was especially conditioned by class politics and working class cultures in the US and UK.5 However, the history of punk and its manifestations is more complex than this common description conveys. For instance, punk scholars such as Dick Hebdige, Paul Gilroy, and Fiona Ngo re-place punk within a transnational context rather than framing it as something that was exported, like imperialism, out to the rest of the world.6

Though it was not entirely inhospitable to women and feminism, punk has also been widely criticized as a white masculinist form of rebellion. This is perhaps especially true of the hardcore subgenre, which came to the fore in the 1980s and often manifested a more specifically macho aesthetic. As Gale Wald and JoAnne Gottlieb note, “Among male punk and hardcore performers, there is a long tradition of this rebellion being acted out at the expense and over the bodies of women.”7 While hardcore is not a monolithic subgenre, “its aggressively masculinist, mid-1980s incarnation stymies any easy historical progression from early women punk rockers to contemporary riot grrrls;”8 in fact challenging sexism in the punk scene was part of the impetus of riot grrrl.9 At the same time, the hegemonic history of riot grrrl as a response to patriarchy in the punk scene often overlooks the importance of women in early punk and post-punk music (Poly Styrene, Siouxsie Sioux, Exene Cervenka, Lydia Lunch, Nina Hagen, the Slits, and the Raincoats to name a few),10 and the ways in which early punk women challenged the male gaze by manipulating the tropes of disrespectable or fallen womanhood,11 a tactic riot grrrl inherited. Moreover, many young girls sought out punk culture as a supportive space in which to reject gender norms and resist patriarchy.12 The standard riot grrrl historiography in mainstream media and often from members/within the movement itself overlooks these nuances, relegating the movement to a mere response to patriarchy. Naturalizing and commodifying gender difference, that narrative also treats women as novelties in accordance with standard practice in rock and popular music, particularly at a time when women rock musicians were a hot commodity.13

Conventional historiography also contains and downplays the issue of race, despite its importance in and to punk. For instance, negation of or distance from whiteness was often considered shorthand for punk authenticity, or analogies were made between being/looking punk and/or working class and being a person of color. (Patti Smith’s “Rock n’ Roll N-” and the Avengers’ “White N-” exemplify this.14) Along with perpetuating the colonial fetishization and surveillance of people of color, such analogies reinforce white privilege by failing to understand racism as a social structure that places people in vastly different proximities to oppression, poverty, and violence. The contributions of people of color to punk have also been erased or overlooked. Relevant here is a special issue of Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, “Punk Anteriors: Genealogy, Theory, Performance,” that centers on “punk anteriors;” that is, as editors Fiona I. B. Ngo and Elizabeth A. Stinson state, the issue retells punk stories to reflect the “foundational disruptions” of critical race and feminist thought in punk music, ethics, and aesthetics.15 The writers in the issue remind scholars that women and other people of color were already creating punk cultures, aesthetics, and performances, despite the prevalence of white men in mainstream genealogies. For instance, Ngo shows how the imperial logic of the US in the 1970s following the Vietnam War “creates the means for understanding and producing punk’s resistant subjectivities…For punks, this meant that the creation of resistant subjectivities happened over and against the real and imagined personages of Southeast Asia.”16 Mimi Thi Nguyen, arguing that women of color were essential to the formation of riot grrrl, exposes the ways that the dominant historiographies of riot grrrl in mainstream media and within/from the movement itself contain the disruptions of race.17

Conventional historiography in the mainstream media likewise tends to overlook or erase the influence of lesbian feminism and queercore punk, though these influences are more visible within riot grrrl. Mary Celeste Kearney argues that the mainstream media narrative of riot grrrl as a response to misogyny in the punk scene reifies the movement as all about music and fails to consider the influence of lesbian womyn’s separatist practices and community that developed out of the radical wing of feminism in the 1970s and included DIY efforts. Kearney shows that riot grrrl descended from lesbian separatist ideology that aimed to resist patriarchy by creating alternative institutions and cultural expressions separate from the mainstream. These included zines and independently produced music, record labels, and music festivals.18 Mainstream accounts have also elided the influence of queercore punk, a subgenre of punk that focused on the oppression and alienation of LGBTQ persons and explored gender and sexual identities. Riot grrrl and queercore bands such as Tribe 8, Team Dresh, Random Violet, and The Mudwimmin emerged at the same time, the two movements engaged each other and overlapped, and for some riot grrrl provided a refuge from homophobia in the punk scene and from the conformism of mainstream gay culture.19 Kearney points out that the erasures of links between lesbian feminism, queercore, and riot grrrl in media are “somewhat obvious attempts to distance this radical female youth culture from the taint of homosexuality.”20

The more mainstream gains and rhetoric of earlier US feminisms also undergirded the rise of riot grrrl. While a thorough discussion of the impact of earlier feminisms and particularly those of the “second wave” in 1960s and 1970s21 is beyond the scope of this essay, a very brief, general history provides important context. Riot grrrl was formed in a world in which the previous generation of feminists had gained certain reproductive rights (especially the right to choose abortion, with Roe v. Wade) and welfare rights; the fight for equal pay was ongoing. Riot grrrl inherited the tactic of consciousness raising, and with the second wave insight that “the personal is political,” riot grrrls also inherited a powerful language to address the violences of patriarchy, to form a collectivity, and to assert autonomy. At the same time, the mainstream second wave agenda of equal pay and reproductive rights, largely the concerns of white middle-class women, alienated many women of color, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer women, working class and poor women, women from developing nations, and young women.22 Moreover, framing the women’s movement in this particular way occluded other important feminist efforts such as the work of women of color to secure welfare rights23 and the DIY efforts of lesbian separatists. There were other points of contention as well. In the 1980s, debates over pornography, censorship, and sex work consumed and had divided the mainstream feminist movement. Andrea Dworkin and others zeroed in on porn and sex work as the key means and ends of patriarchy. Meanwhile, radical and Pro-Sex feminists such as Pat Califia argued the that women’s relationships to porn, sex work, and BDSM were complicated, particularly for queer women, and could challenge patriarchy in exciting ways and be pleasurable. Pro-Sex or Sex Radical feminists, like many punk women, challenged the de/valuation of women based on notions of respectability. Other feminists pointed out that these concerns were once again white and middle-class and called for attention to the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, nationality, etc.24

Academic feminisms also both fueled and failed riot grrrl. On one hand, attention to difference and diversity (a legacy of women of color feminisms), an increasing consideration of young women, and the influence of postmodern theories of fluidity and the instability of identity (what would come to be known as queer theory) were becoming more prevalent in academic feminism.25 Third wave feminists were influenced by and living the realities of such ambiguity, for many of them had benefitted from the gains of second wave feminisms and come of age in a time of extreme political conservativism and backlash. Many also grew up identifying as bisexual, transgender, and interracial.26 On the other hand, many riot grrrls felt that academic feminism did not speak to their needs and was not pragmatic in terms of improving the material realities of young women’s lives.27

The neoliberal backlash against feminism(s) also influenced the emergence of riot grrrl. Karen Orr Vered and Sal Humphreys have canvassed how and why postfeminism, which is constituted through previous feminisms, is prevalent in media in the neoliberal conjuncture.28 As an analytical tool, the term, “describes the political moment in which the material and ideological gains of second-wave feminism have been accepted and incorporated into our mainstream values and common ambitions at the same time as neoliberal economics and its associated social policies—including a reduction in social welfare support—have become entrenched.” Assuming that equal opportunity, wage equity, and autonomy (the goals of mainstream second wave feminism) have been established, agency for change is placed on the individual rather than with collective action or on society; women are “encouraged to concentrate on their private lives and consumer expression as the sites for self-expression and agency.”29 By the early 1990s, neoliberalism, with its ethos of personal responsibility, individual freedoms, and consumerism, was ostensibly a postfeminist and also “colorblind” system.

Yet in the 1990s tangible proof that feminism was necessary and that women were taking notice was building. There were multiple high-profile acts of violence towards women in the 1980s, such as the Green River Killer’s murder of over forty girls and young women, the 1989 rape of a female jogger in Central Park, and the 1989 massacre of female engineering students in Montreal by a man who, only after asking all the men to leave the room and then declaring that the female students were all feminists and he hated feminists, opened fire.30 The Clarence Thomas hearings in 1991, in which the victim of his sexual harassment, black American Anita Hill, was interrogated and dismissed by a panel of white male senators, provoked new national interest in feminism or at least women’s rights. With the 1992 presidential election, women’s rights and especially women’s right to abortion were under fire as the Republican Party collaborated with the religious right; sexual harassment and “date rape” were ubiquitous;31 and given the ongoing wage gap and gender gap in education, women and people of color were especially impacted by declining income and standards of living. Although Susan Faludi’s 1992 Backlash, an examination of antifeminism in the 1980s into the early 1990s, was a national bestseller, the moralism of the Right combined with neoliberal personal responsibility rhetoric to place blame—for harassment, date rape, violence, poverty, etc.—squarely upon individual women. In other words, postfeminist ideology conveyed the message that if women were experiencing violence, sexual harassment or any iteration of misogyny or sexism, they had somehow eschewed personal responsibility for their life and actions and should be ashamed of their behavior. Shame and shaming disciplined women and concealed the systemic operation of power in the “postfeminist” United States of America.

Finally, young women were directly experiencing the violences of misogyny and sexism. The neoliberal system’s absorption of the rhetoric of second wave feminisms led to the superficial appearance and ideology that girls could do or be anything they chose, that feminism had done its job and removed sexist barriers. Yet as Sara Marcus puts it, teenage girls, “living some of the thick residuals of sexism the feminist movement hadn’t managed to destroy,” had been told that they

could do anything except walk down the hall by the shop classroom, anything except stop shaving their legs, anything except wear that skirt to the party, anything except play drums without being exclaimed over like some sort of circus seal, anything except choose sex and not get whispered about as a slut.32

In the wake of earlier feminisms, many girls had an awareness that things should and perhaps could be different.

Thus the punk movements and feminist movements and the complexities of neoliberalism set the stage for riot grrrl. Following Nguyen, as well as Ngo and Stinson’s “concerns about the often unequal distribution of punk’s resistant stances,”33 what follows in this essay evaluates riot grrrl uses of shamelessness as feminist resistance, specifically through body writing as an act of sociocultural reappropriation and as emblematically performed by Kathleen Hanna, arguably the most visible riot grrrl. As has been the case with other iterations of punk and feminism, race-based exclusions and inclusions shaped politics and performances, though in dominant historiography this is erased or downplayed.34 In the 1990s the erasure or minimizing of attention to race and also class occurred in forms specific to neoliberalism. As such, this interrogation of riot grrrl performances of shamelessness contributes to discussions of punk and feminist racial formations in the context of neoliberalism. My hope is that it will generate a productive dialogue.

“When she talks, I hear the revolution.”

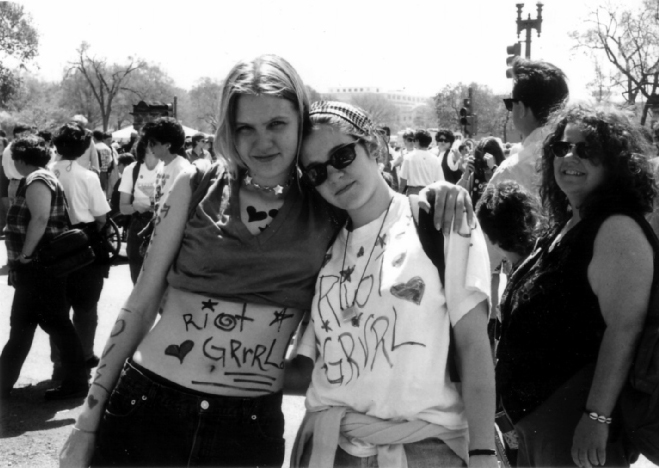

Riot grrrl formed in 1991 in punk communities in Washington, DC, and Olympia, Washington, and from the start DIY shameless feminist cultural production was its primary method of resisting patriarchy. Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman, members of the band Bratmobile, worked with fanzine editor Jen Smith to establish the collectively written feminist zine Riot Grrrl. Zines are homemade publications that include articles, art, poetry, fiction, and manifestoes that are photocopied and distributed. Simultaneously, Hanna, creator of the feminist zine Bikini Kill, which preceded the band, began organizing weekly “riot grrrl” meetings.35 In the 2013 biopic The Punk Singer, Hanna said that the band, and the movement it was a part of, wanted to reclaim girlhood.36 Although Hanna—who penned the lyric, “When she talks, I hear the revolution” for the Bikini Kill song “Rebel Girl”—has resisted her designation as the “leader” of the movement, I focus on her because she was one of its founders and significantly shaped its methods and legacy. She is the best-known riot grrrl, and her performances of shamelessness with Bikini Kill were also the most visible; in fact it was she who inaugurated the practice of body writing/word reclamation. While many bands in addition to Bikini Kill were important to the movement, and while there were many 1990s bands involved in leftist political causes, in-depth exploration of all of these is beyond the scope of this analysis.

The grassroots feminist movement, which was intentionally loose, never centralized, and which proliferated all over the US and the world, was about politically empowering and mobilizing young women, particularly through independent cultural production that challenged notions of feminine respectability and disrespectability. Riot grrrl sought to create and sustain space for an inclusive feminism that could, as Rebecca Walker said of third wave feminism in general, “accommodate ambiguity and our multiple positionalities: including more than excluding, exploring more than defining, searching more than defining.”37 In fact Hanna pointed out in a 2014 lecture at New York University that the Riot Grrrl Collection at NYU’s Fales Library and Special Collections reflects intentional flexibility, with multiple narratives and types of materials,38 and its inclusion in a library is itself a form of resistance.39 Meetings held from 1991 through about 199640 provided a place for girls, most of whom were in their teens and early twenties, to connect and find support: meetings normalized the experiences of girlhood under patriarchy, taking young women out of the isolation of the capitalist narrative that there was something wrong with “me” that might be “fixed” with a commodity and/or more self-discipline or modesty or discernment or less assertion or aggression or feminism. In other words, these meetings, along with DIY cultural production/consumption that allowed girls who were geographically distant to connect, empowered girls to politicize what they previously experienced as only personal. Breaking silence within a supportive community of girls was personally transformative for many, and was meant to be a starting point for collective social action and political change41—though the latter did not necessarily follow from the former: as Nguyen has pointed out, what she calls riot grrrls’ “politics of intimacy” (that is, girl love and self-referentiality) had racialized, classed contours that upheld rather than challenged the neoliberal status quo. While I explore this in depth below, first I provide an overview of the movement and its practices.

Riot grrrl used a variety of methods to connect, support, and mobilize girls. As Hanna said, “punk is an idea, not a genre;” the idea is that we can create culture, and corporations are not going to tell us what culture is.42 Zines were one key way that riot grrrls created and disseminated their own culture. While the origins of zines are unclear, from the late 1980s through the mid-1990s (when the Internet began to dominate communication), zines proliferated as way to create and share information without permission, rules, or restrictions.43 Zines anticipated the democratizing aspect of the Internet, in that at minimal cost, and without the interference of elite publishers and corporate gatekeepers, almost anyone could create and distribute a text that would find an audience.44 Zines often looked intentionally crude, literally involving cutting and pasting text, images, etc., so that the form itself reflected a rejection of the “status quo of professionalization.”45 Content was equally resistant: like most zines in the 1990s that aimed to exchange information,46 riot grrrl zines were a way to form support networks and create safer spaces to examine and challenge sexism creatively, and shamelessly.47 To challenge the “passive consumption mindset produced by mainstream capitalist media,” zines “intentionally attempted to interrupt assumptions about femininity and force the reader to reconsider how femininity and pleasure interface;” therefore, “zines are playing in the spaces between resistance and complicity and as such are creating third wave tactics.”48 The zine distribution network Riot Grrrl Press was created in 1993 in Washington, DC, by Erika Rienstien and May Summer to combat the media’s appropriation of riot grrrl, while spreading the word about the movement, at minimal cost and zero profit.49

Yet participating in zine culture, while more accessible than playing in a band, required leisure time to create zines, access to photocopy machines, money for supplies and stamps, and “enough self-esteem and encouragement to believe that one’s ideas and thoughts are worth putting down for public consumption—all marks of a certain level of privilege.”50 And while women of color and working class women created zines, the zines that have received the most attention were disproportionately created by white, middle-class young women.51 Thus zines were not and could not be (feminist) utopian cultural productions, but rather were polysemous, their production (and consumption) both subverting and supporting the status quo.

Music was also an important part of riot grrrl and was equally polysemous. Along with Bikini Kill, bands such as Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsey, Sleater Kinney, Team Dresch, 7 Year Bitch, Sta-Prest, Tribe 8, and Huggy Bear were also key to riot grrrl. Hanna, who was well-versed in feminist theory and feminist art history, formed Bikini Kill, her third band, with the same impetus underscoring the zine of the same name: getting her feminist message out to young women, and encouraging them to take control of their own cultural production. She put “girl” and “power” together to combat sexism and the feminist erasure of girls that followed from the 1970s focus on empowering “women.”52 Along with Hanna on vocals, Tobi Vail was on drums, Kathi Wilcox on bass, and Billy Karran on guitar. Like other punk bands, the sound was aggressive, energetic, and loud. Unlike most other punk bands (though part of the legacy of women in punk rock), Hanna and the other two female band members were at the center, boldly taking up space as they decried sexism and embraced aspects of normative femininity with their songs, words, and performances. Hanna showed young girls that it was possible and acceptable to be angry, smart, sexy, loud, and ugly in uneven and contradictory ways; being a young woman was all of these things. Communicating with women and men about sexism underscored all of Hanna’s art, zines, and music, and with Bikini Kill she did this by often singing to “an aggressive asshole male.”53 For instance, in the song “White Boy,” Hanna calls out a white boy/man for treating women like objects and like they are “asking for it”—that is, rape and/or sexual harassment—with what women wear and how they act. “White Boy” assailed slut-shaming and sexist victim blaming, a facet of the neoliberal rhetoric of personal responsibility that so chillingly masks structural causes of rape, violence, and oppression. Unlike most music aimed at young female audiences in the 1990s, which tended to focus on heterosexual romance while affirming patriarchal norms, riot grrrl bands focused on violence against women and female empowerment via “girl love”—that is, connecting with and supporting one another.

Riot grrrl bands also encouraged young women to play in bands, and wanted women to be safe from sexual harassment and violence at shows. These concerns are evident in the riot grrrl imperative, “girls to the front.” At shows, women were invited to come up to the front of the stage and directly engage with bands without being intimidated, harassed, or abused by men in the audience, as was common at 1990s punk and hardcore shows. Interest in bands also helped young women to connect even when they were geographically distant. In this way, bands reclaimed female fandom as transgression and encouraged young women to be subjects rather than passive consumers, even if they did not play instruments.

Yet being a musician required capital, ability, and leisure time. Many could not afford instruments or lessons, could not spare the time to practice, or simply were not musically inclined. White cis-gendered women also populated most of the bands inspired by riot grrrl; this was certainly true of those that received the most recognition. Though riot grrrl’s culture of music was meant to be participatory and active, like zine-making, racial and class privilege circumscribed access.

Riot grrrls were also active in more traditional forms of protest, though personal transformation via a “politics of intimacy” and cultural production was at the heart of the movement. Many participated in marches and benefits (there were numerous pro-choice marches and benefits in Washington, D.C., in the 1990s, given that Roe v. Wade was under attack). Other actions included escorting women to and from abortion clinics, and distributing flyers and zines to women in a variety of inventive ways.

Body writing/word reclamation was one of the most controversial ways that riot grrrls conveyed their messages and connected with one another, and it encapsulates the pitfalls and possibilities of shamelessness in the context of a “politics of intimacy.” It is this practice that I am most interested in evaluating as an emblematic riot grrrl method of shameless feminist resistance.

******

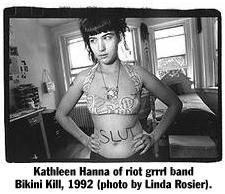

“A girl’s body was contested territory; this was a way to rewrite its meaning.”54

At a show in Washington, D.C., in June of 1991, at the end of Bikini Kill’s first tour, Hanna performed with “SLUT” written in black magic marker across her exposed stomach; she shamelessly bore and thus reclaimed the label so often used to shame young women in a patriarchal culture that simultaneously normalizes the sexual objectification of women and devalues women for being too sexual or inappropriately sexual. Gottlieb and Wald observed that riot grrrl’s deployment of the body in performance functioned as an antidote to violations of women’s bodies—overdetermined femininity, rape, incest, physical abuse, and eating disorders, to name a few—in a sexist society.55 Bikini Kill epitomized this tactic, as they

encourage[d] young, predominantly white middle-class girls to contest capitalist-patriarchal racism and sexism, precisely through acts of individual transgression against the implicit or explicit norms of “ladylike” or “girlish” behavior. The band linked these individual challenges to private (that is, domestic, local or familial) patriarchal authority to collective feminist resistance and struggle.56

With her inaugural individual act of sociocultural reappropriation, Hanna established a paradigm for riot grrrl word reclamation as a protest performed through the body.

Body writing comes out of the legacy of feminist art history (which Hanna had studied as an art student at Evergreen College) and 1980s radical activism. Female artists in the 1960s and 1970s had made their bodies sites/works of art to call attention to women’s roles, limits, and possibilities. In the 1980s, much like advertising (and thus pointing directly to the role of commodification/consumerism in creating social injustice and violence), some feminist artists and ACT UP used images of clear language and words to convey their messages. For example, an ACT UP protest poster featured a photo of Ronald Reagan’s face and the word “AIDSGATE” printed across the bottom,57 criticizing Reagan’s lack of action and honesty in the AIDS crisis by likening it to Watergate.

Hanna, intentionally combining feminist art and activist visual forms, invited girls to use their own bodies to talk back to the politics of respectability and gendered shaming. Body writing was soon taken up to allow riot grrrls to publically proclaim things (about sexism, girlhood, and really any topic they chose) and to help them identify and thus connect with one another; in fact there was a specific call to do so in the article “Let’s Write on Our Hands” in a 1991“female revolution” flyer created by D.C. riot grrrls. While Hanna most frequently wrote “SLUT” on her own body, girls were invited to choose the words and images, such as hearts and stars, which resonated with them. This practice, which also nods to the straightedge punk practice of writing large X’s on the backs of one’s hands to signify drug-free status,58 encapsulated third wave feminism’s new attention to individuality while also helping young women to recognize and connect with each other, and helping those who were geographically isolated knew that others were doing the same thing. Given the impermanence of magic marker (as opposed to the permanence of tattoos), what one wrote could change and was thus fluid, making body writing an especially apropos act of resistance within a movement that embraced contradictions and fluidity.

Body writing was also perhaps the most materially accessible means of participation in riot grrrl. It was free (one could easily use or steal a magic marker) and far less labor-intensive and immediate than creating a zine or playing in a band or even acquiring a zine or a tape; in that regard, body writing is a strong example of the punk DIY ethos that invites all to participate. Moreover, unlike zine-making and playing in a band, body writing is essentially outside of exchange value. While zines and bands may not have been motivated by profit, they were created and distributed within/under the constraints of capitalism, whereas with body writing there is no product or an organization of labor. Additionally, given that magic markers come in a variety of colors, it was potentially inclusive to people with a variety of skin tones.

However, access to body writing as a performance of shameless feminist resistance was limited by the socioeconomic systems that made it legible; body writing/word reclamation was quintessentially neoliberal. Angela McRobbie describes the neoliberal “disarticulation of feminism” in British culture, in which feminism has been reshaped into an individualistic discourse that reestablishes traditional ideas about women and as such combats the formation of a new women’s movement. Women must consent to this in order for it to reproduce itself.59 By failing to consider how race and class shape gender deviance, word reclamation via body writing disarticulated feminism and could perhaps be considered postfeminist, as it exemplifies a broader neoliberal thread.

Nguyen proposes that the movement’s “politics of intimacy” and aesthetics of access to the means of production, creative labor, and expertise and knowledge “through which the personal and political are collapsed into a world of public intimacy”60 reproduces white middle-class privilege, and conceives of change as an individual rather than collective endeavor.61 This model of intimacy was celebrated in early scholarship on riot grrrl, as seen in Jessica Rosenberg and Gitana Garofalo’s 1998 interview with several riot grrrls, published in Signs. The piece is tellingly called “Riot Grrrrl: Revolutions from Within.” In their introduction to the transcript, they note that the movement “focuses more on the individual and the emotional than on marches, legislation, and public policy. This creates a community in which girls are able to speak about what is bothering them or write about what happened that day.”62 For instance, eighteen-year-old interviewee Lailah Hanit Bragin states, “If writing is revolutionary, just being honest and talking about your life is revolutionary. If everyone did that, it’d change things. If you start to chip away at walls that are within you, you’ll eventually get revolutionary writing.”63 “Revolution” therefore begins and ends with individual awareness and action. Lailah even goes as far to state, “The revolutions are revolutions from within:” riot grrrl allowed her to change core things about herself and things around her. She does not specify what this latter part means, and the piece ends with her words.64

Nguyen is not at all dismissive of the power of riot grrrl’s new iteration of “the personal is political,” nor am I. It allowed young women to realize that their personal experiences and feelings could be political and ideological; intimacy in terms of violence, rape, incest, and simply dating in a patriarchal world were explored in depth, and self-knowledge and disclosure, framed as opposition to capitalism, misogyny, etc. provided a foundation for connection that was accessible to many adolescent women. Additionally, intersectionality was not invisible, nor did all women of color feel marginalized, or at least not always. In Rosenberg and Garofalo’s interview, for instance, Madhu Krishnan, who identifies herself as “an indian [sic] of American descent,” the child of immigrants who “have done wonderfully well, by any standards,” states that “the main thing about riot grrrl that I find so attractive is how it made me feel connected with all these girls from hundreds of miles away.” Madhu notes that intersectionality is necessarily a part of the movement,65 a point other interviewees noted as well.66 Many interviewees likewise stressed that the movement allowed them to politicize what they thought was merely personal, and that in connecting with other girls via zines, bands, and online communities, they found community and hope.67 Others made the point that the confessional form of girls writing about really personal issues builds trust, and is underscored by “girl-love.”68 This is ostensibly inclusive. Yet as Nguyen points out, the focus on aesthetic forms and intimacy

emerging during the 1990s to now, register how neoliberalism and its emphases on the entrepreneurial subject shapes even progressive or feminist adjustments to the structural determinations that constitute the historical present, engendering an emotional style, and a rhetorical practice, that sometimes glossed intimacy for reciprocity, experience for expertise, and misrecognized how forces work through these idioms.69

The ways that shame and shamelessness functioned within the movement as modes of resistance are indicative of this neoliberal pitfall. Zines often included public “confessions” of privilege (white, hetero, skinny, etc.) and “calling each other out” on privilege was common. For instance, Erin A. McCarley, interviewed by Rosenberg and Garofalo, states, “I find so much more girl-love with girls who’ve called me on being classist or racist.”70 The confession of shame functioned as accountability, the confessor allegedly transformed by it.71 While “calling each other out” is a communal practice, it engendered only an individual declaration without any attendant structural action or critique; the acts of “calling out” and confession were themselves considered transformative.

Performing shamelessness via body writing and also sex work was similarly problematic in terms of its exclusivity and preclusion of structural critique and action. Women of color within the movement

wondered out loud for whom writing “SLUT” across their stomachs operated as reclamations of sexual agency against feminine passivity, where racisms had already inscribed such terms onto some bodies, and poor or criminal-class women argued that feminists “slumming” in the sex industry (through stripping, for the most part) as a confrontational act implied that other women in this or other tiers of the industry were otherwise conceding to patriarchy.72

Failing to consider that women of color and poor women often lacked the choice to claim gender deviance as transgression, given that they are often characterized as always already deviant and disrespectable, white, middle-class privilege was reproduced. Body writing/word reclamation, a variation of the public confessional, also runs the risk of substituting an individual act for actual connection with a collectivity and social action.

The way that class likewise overdetermines women’s sexual choices was also underexamined. As noted earlier, a “politics of pleasure” and prosex politics were one of the strongest threads of feminism in the 1980s into the 1990s.73 Including and beyond riot grrrl, many third wave feminists zeroed in on the radical potential of sex work, understanding it as more than an instrumental result of patriarchy and focusing on choice (some women choose to do sex work), financial stability, and the pleasure and power that can be had in sex, sexiness and control of one’s own sexualization. Like body writing/word reclamation, performing sex work was often considered “objectification as anticipatory retaliation: they were taking back that male gaze and making money off it to boot.”74 Hanna was a stripper and considered it a choice she had made, and many riot grrrls worked as strippers. However, the de-materialized rhetoric of choice erases the women who lack choice; that is, women who, because of poverty or abuse, and who were often disproportionately of color, had to do sex work to survive. Like gender deviance in general, it overlooks the casting of women of color as always already deviant; for instance, black women and Latinas are rendered “unrapeable” because of stereotypes of hypersexuality/sexual availability, lingering legacies of slavery and colonialism. Moreover, only individual women may benefit from the wages they earn, while the system not only remains intact but also is supported by their actions. The fact that selling her own body is one of the most profitable things some women can do also indicates that we are not a society that no longer needs feminism. Additionally, third wave prosex politics were quickly commercialized in a “do-me feminism” in which any sort of sexiness or really any choice a woman made could be labeled “feminist,” even if that “choice” was to adhere to patriarchal norms. A woman who chose to wear conventionally sexy clothing to please a man, for instance, was framed as feminist. This is postfeminism, or the disarticulation of feminism.

Nguyen also shows how riot grrrl’s politics of intimacy circumscribed productive, meaningful critiques of racism within a movement that sought to combat it. First, efforts to eliminate distance from racial Others with confessionals and intimacy (thus ignorance and distance are posited as the causes of racism) is aligned with colonial, imperial histories in which surveillance required certain people to reveal themselves so that white people could learn about “difference.” This notion of antiracism burdens people of color as educators, and interventions are stuck at the “personal” level, at overcoming ignorance and perhaps making some friends of color. In other words, taking personal responsibility is, again, posited as the solution to structural oppression. Second, just as white ethnic feminists in the 1960s and 1970s asserted commonality with people of color and recent immigrants75 and as is common in punk, with this politics of intimacy “the authentic (white) self is enhanced through proximity to the racial, colonial other.”76 Third, as in earlier feminisms, women of colors’ critiques of racism were dismissed as divisive, and this characterization persists, for example in Grrrls to the Front.77

Additionally, body writing/word reclamation was easily commodified in the mainstream media and could be considered an early iteration of “do me” feminism. This points to the complicated relationships between bands, fans, and the music industry and media that exploited riot grrrl for profit and the polysemy of texts and performances. While this complexity calls for more in-depth exploration than I can provide here, the mainstream representation and cooptation of riot grrrl body writing is revealing. Summer points to the publication a 1993 Spin article that depoliticized riot grrrl as a critical moment that motivated the formation of Riot Grrrl Press. What cofounder Reinstein told a reporter was distorted in the article, and in the photo spread the magazine used a thin, conventionally attractive model to portray a riot grrrl: topless, with words such as “bitch” and “slut” written on her body. The political practice of body writing/word reclamation was thus presented as a fashion statement, and riot grrrls were portrayed as sex objects, their message domesticated and commodified.78

On the other hand, negotiation of the meaning and value of media is fostered by the commercial logic of mass media (designed to be popular and “relevant” to consumers);79 by the inevitable disruptions intrinsic to hegemony, given that it is produced rather than natural or given—“there are always cracks and contradiction, and therefore opportunities;”80 and by the “wild card” of audience reception—stereotyping and marginalization in media may acculturate viewers to the status quo or provide them with a means to resist it.81 The mainstream presentation of riot grrrl may have introduced young women to riot grrrl and/or empowered them in other ways,82 and the formation of Riot Grrrl Press shows that it (re)galvanized women already in the movement. In fact, riot grrrls enacted a media blackout to resist the commodification and consolidation of their identities. In 1993, when the media blackout became official, riot grrrls agreed to share with reporters only the address of Riot Grrrl Press, so that information about the movement could still get out.83 When some did opt to engage with mainstream media, they emphasized that riot grrrl was not about a particular kind of girl, not about the individual (which is what the media emphasized, usually in the most unflattering terms). Grrrls stressed that the movement was meant to be an inclusive, collective feminist revolution.84

Body writing/word reclamation itself could also be considered polysemous. When, in the Q&A of her May 2014 lecture at NYU, I asked Hanna directly about her feelings about the efficacy of it, she said that at age forty-five she feels sad when she looks at the famous picture of her with “SLUT” written across her stomach because “you feel like someone is going to punch you in the face, so you punch yourself in the face.”85 Hanna acknowledged that this was no game-changer; body writing/word reclamation did not alter the oppressive social structure that created a need for feminist resistance and in a sense it actually echoed it. Additionally, the signifier cannot be controlled; there is the “wild card” of audience reception, so that spectators might take this performance of shamelessness literally. These issues, combined with the white middle-class privilege delineating the contours of body writing/word reclamation, indicate that it is a problematic performance of feminist resistance.

Yet Hanna also acknowledged the power and possibility of body writing/word reclamation in terms of taking control of one’s own body, talking back to patriarchy, and forcing others to confront the male gaze.86 I too wonder about the productive potential of the practice, if any, given that it does directly respond to and trouble the age-old patriarchal division of women into respectable and disrespectable categories that are always already racialized.

In accordance with third wave ambiguity and intersectionality, body writing/word reclamation invited spectators, viewers, and co-travelers to question and explore rather than define. What is problematic is that it is a racialized, classed invitation that is accessible only to white middle-class women. Ironically, the reclaiming of pejorative words is connected to and part of the practice of minoritized groups reclaiming words used to insult and stigmatize them, as with the reclaiming of the word “queer” to signify a fluid, flexible sexuality and political identity that rejects binaries, categories, and the fiction of stable identity. “SLUT” was not claimed as a political identity, but it was another instance of the shameless reclaiming of a label used to discipline and control a population, a rejection of the politics of respectability, and an instance of girls taking control of their own bodies at a moment in which social institutions were working assiduously to interpellate them in perhaps new ways. It is a limited, exclusive tactic of resistance that gels with neoliberalism’s blindness to structural oppression (a la “colorblindness,” personal responsibility/the politics of intimacy, and postfeminism). But word reclamation through body writing was meant to expose rather than reproduce blindness and inequality, and it did rather directly growl back at aspects of patriarchy, connect if not galvanize some young women, and engender insightful and ongoing critique about the racialized politics of gender respectability. Therefore, is body writing/word reclamation entirely useless as a form of shameless feminist resistance? Is there any productive potential in the practice? Can performing shamelessness through body writing/word reclamation be reimagined and deployed as a viable form of queer feminist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist protest? If not, what alternatives are possible?

Smashing/Furthering a Neoliberal Agenda?: The “Daughters of Riot Grrrl”

The transnational grassroots SlutWalk movement, which began in Toronto in 2011 and is ongoing, is a direct descendant of the riot grrrl practice of body writing/word reclamation and its impetus to challenge the patriarchal politics of respectability.87 As such, it is similarly polemical. The discussions around race and gender respectability that SlutWalk has engendered suggest that performing shamelessness could potentially be re-imaged in ways that meaningfully combat the gendered and racialized violences of neoliberalism.

The movement protests rape culture and victim-blaming; specifically, SlutWalks began in response to Toronto police officer Michael Sanguinetti’s remarks to law students. While giving a talk on health and safety he said, “Women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimized.”88 SlutWalk’s impetus is to challenge rape culture—that is, a culture that supports and rationalizes objectification of and violence against women—and its name is a direct response to Sanguinetti’s statement.89 Like neoliberal culture in general, within rape culture the victim rather than the social system that produces and justifies violence is blamed; the rape culture narrative asserts that women are victimized because they fail to take personal responsibility to not look like or act like sluts; they are disrespectable.

SlutWalks usually take the form of traditional marches and may include women wearing revealing attire and with body writing words such as “SLUT” (though this is not required). Events often also feature speakers, workshops, music, dance, and other activities to create connection and community, all with the goal of taking collective action against victim-blaming and supporting the survivors of sexual assault, and with attention to how intersections of race, sexuality, dis/ability, and class make women vulnerable to violence in specific and often disproportionate ways.

Like riot grrrl body writing/word reclamation, with performance (in this case a public march) the SlutWalk movement attempts to challenge people to confront their biases and prejudices by calling attention to slut-shaming as a pervasive form of sexist violence that is carried out by individuals and sanctioned by social structures. SlutWalk has also been credited with making feminism “cool” or at least compelling to a new generation of young women.90 It has been critiqued by a host of women as well for failing to consider race, for simply perpetuating patriarchal objectification, for not rendering a proper structural critique of the sex industry and sexual violence against women, and for substituting acceptance of dress and the term “slut” and the act of marching for structural change. In short, it has been critiqued along the same lines as riot grrrl body writing/word-reclamation.

In terms of race, although the SlutWalk movement also aims to address intersectionality, it has been a topic of much debate among women of color and especially black women. On one hand, SlutWalk, like riot grrrl body writing/word reclamation, is predicated on gender deviance that overlooks the historical and present-day hypersexualization of women of color; for some women of color, an always already assumption of sexual shamelessness is the problem, not its antidote. In “An Open Letter from Black Women to SlutWalk Organizers,” posted on September 23, 2011, by Black Women’s Blueprint and signed by a number of organizations and individuals, the issues are made clear:

As Black women, we do not have the privilege or the space to call ourselves “slut” without validating the already historically entrenched ideology and recurring messages about what and who the Black woman is. We don’t have the privilege to play on destructive representations burned in our collective minds, on our bodies and souls for generations. Although we understand the valid impetus behind the use of the word “slut” as language to frame and brand an anti-rape movement, we are gravely concerned. For us the trivialization of rape and the absence of justice are viciously intertwined with narratives of sexual surveillance, legal access and availability to our personhood. It is tied to institutionalized ideology about our bodies as sexualized objects of property, as spectacles of sexuality and deviant sexual desire. It is tied to notions about our clothed or unclothed bodies as unable to be raped whether on the auction block, in the fields or on living room television screens. The perception and wholesale acceptance of speculations about what the Black woman wants, what she needs and what she deserves has truly, long crossed the boundaries of her mode of dress.91

Others have countered that this line of criticism falls back on rather than challenges racist patriarchal violence that de/values women based on a politics of respectability. On the Ms. blog for instance, Janelle Hobson wonders about the potential of reframing the movement with the use of the term “Ho,” to center the shaming term more readily applied to black women, and she points out that being “respectable” does not prevent a woman from being raped.92 Andrea Plaid, while acknowledging that SlutWalk “came off as another word-reclamation project that seemed to recenter white cisgender women’s sexual agency and bodies (sort of the way ‘feminist issues’ tends to reincarnate a little too often as ‘white (cis) women’s issues’),” was also concerned with criticisms of the movement that supported a politics of respectability. She too argued that the movement’s concerns and impetus did apply to and have the potential to empower women of color. Consequently, she chose to join the movement along with several other women of color and volunteered to speak at the then upcoming SlutWalk NYC.93 Hobson concluded that feminists have not effectively taken on the splitting of women into respectable and disrespectable and “as long as that split remains, it will encourage the dehumanization and disposability of women framed as ‘sluts’ and ‘hos,’ while encouraging other women to be complicit in order to hold onto their ‘respectability.’” She asserts that SlutWalk “boldly” takes on a word used to shame and thereby silence women “and in doing so, invites us to empty it of its power and its racist, classist, hetero/sexist meanings.”94

A sustained discussion of whether or not subsequent SlutWalks can, as Black Women’s Blueprint put it, “develop a more critical, a more strategic and sustainable plan for bringing women together to demand countries, communities, families and individuals uphold each others [sic] human right to bodily integrity and collectively speak a resounding NO to violence against women,”95 is beyond the scope of this analysis. It is worth noting that some efforts have been made to be more inclusive. For instance, the Chicago march was promoted in Spanish and English, and organizers expressed a desire to avoid the mistakes—that is, racial exclusions—of previous feminist movements.96 This example seems to run the risk and perhaps did succumb to the pitfalls of riot grrrl and other feminist movements in terms of failing to radically incorporate the concerns of women of color, centering them rather than including them as add-ons meant to enhance privileged feminisms. This is what neoliberal “inclusion” and “equality” looks like: tokens of “difference” added without any structural changes, it is merely cosmetic inclusion or equality, the status quo enhanced with an update of “difference.” As Nguyen says, an important lesson learned from riot grrrl is that “feminist futures cannot look like feminist pasts, in which the interventions of women of color are incorporated as a brief disruption into a feminist teleological time that emphasizes origins, episodes, and successions.”97 Whether or not SlutWalk can move past this remains to be seen, though I am in agreement with Hobson and Plaid in that it seems that the potential is there.

Moreover, the need for truly inclusive feminist futures is extremely important given extant riot grrrl movements. In the 2014 Philadelphia Inquirer article “Daughters of Riot Grrrl,” current feminist activists and artists, many of whom came of age during the 1990s and were part of riot grrrl or heavily influenced by it, such as the group Pussy Division, discuss their work as part of the movement’s legacy. A traveling art exhibit called “Alien She,” the title of a Bikini Kill song, is billed as focusing on riot grrrl’s impact today, and features women’s art, zines, and band posters. The Russian feminist punk group Pussy Riot directly traces their lineage to riot grrrl and bands such as Bikini Kill; riot grrrl groups continue to exist and form all over the world,98 and the Internet continues to support and expand the movement. The curators of the “Alien She” exhibit, Astria Suparak and Ceci Moss, also invite viewers to participate in a riot grrrl census to map groups and to describe how the movement has impacted their lives.99 We can do the same at http://riotgrrrlcensus.tumblr.com. Riot grrrl and its performative tactics of resistance are still with us. So where does all of this leave us in terms of feminist futures?

Conclusion

Riot grrrls were indeed largely white and middle class, as were the movement’s concerns. This is the version of riot grrrl history that dominates; it is the version that is told as the authoritative riot grrrl history, and to an extent it is a history I have retold here. As noted, the movement was not monolithic and did attempt to address intersectionality. In response to accusations of exclusivity, Dunn and Farnsworth noted that many riot grrrls came from lower middle-class and working-class backgrounds; many were women of color; many in college worked to pay their way through school; some worked low-paying jobs, lacking time to produce zines and providing one reason for the formation of Riot Grrrl Press; many worked in the sex industry; and access to photocopying equipment was either the perk of a job or illicitly acquired rather than necessarily a mark of privilege.100 And also, as Nguyen chronicles, women of color were a foundational part of riot grrrl, though that history has been elided in mainstream and riot grrrl accounts. Issues of race, class, sexuality, body size, nationality, and ableism were taken seriously by many riot grrrls. These issues were frequent topics in zines, at meetings, and at the two riot grrrl conventions,101 though unfortunately this usually occurred in problematic ways that perpetuated exclusivity, privilege, and inaction.102

Although intersectionality was not absent in riot grrrl, it was not centered or thoroughly theorized; instead, the concerns of cis-gendered white women counted as “riot grrrl issues.” Too often, merely acknowledging or talking about racism was counted as doing something about it. Riot grrrls’ use of the “self-centered language of adolescence” and the personal story in lieu of a narrative of group oppression103 drew on and perpetuated the neoliberal imperative to take personal responsibility for oneself; it drew on a language that lends itself to victim-blaming, which was antithetical to the movement’s goal to empower women and combat patriarchy and other forms of structural oppression. Body writing/word reclamation and sex work were likewise individualistic and recuperated white privilege and class privilege in the midst of challenging the gendered politics of respectability. In short, riot grrrl politics of intimacy were neoliberal and body writing/word reclamation poignantly emblematizes this.

What may be usable for feminist futures is that riot grrrl performances of shamelessness via body writing were backed by the recognition that individual experiences were all systemically shaped, and the movement’s call for active, material resistance as part of a collectivity was not meant to be narrowly defined. Wald and Gottlieb, reflecting on riot grrrl performances as a whole, said (in 1994):

Rather than reducing the political to issues of self-esteem, riot grrrls make self-esteem political. Using performance as a political forum to interrogate issues of gender, sexuality and patriarchal violence, riot grrrl performance creates a feminist praxis based on the transformation of the private into the public, consumption into production—or, rather than privileging the traditionally male side of these binaries, they create a new synthesis of both.104

Though more critical of privilege in her later work on riot grrrl, Kearney concluded her early study of the influence of lesbian separatist movements on riot grrrl by asserting that the movement was “formed to express rage and ignite female youth” to combat all forms of inequality and oppression, and was doing just that.105 These evaluations were overly optimistic, given the racialized, classed neoliberal limits of riot grrrl’s “politics of intimacy.” But it seems that performing body writing/word reclamation had more than semiotic weight and has productive potential, which the embrace of it by the SlutWalk movement suggests. With radical revision that centers the complex and varied concerns of women of color and also queer women, disabled women, im/migrant women, and women from the global south, body writing/word reclamation seems to have productive potential. In other words, with radical revision that de-centers white, Western, cis-gendered women and is founded in true intersectionality and committed to following with collective action that takes on systemic oppression, properly radical feminist transformation via the performance of shamelessness may be possible.

Epilogue

Then, our attempts to reclaim girlhood were circumscribed by a failure to truly address racism and other forms of structural oppression. Now, the need for effective feminist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist resistance is as urgent as it has ever been, particularly given the prevalence of postfeminism and antifeminism and the myopia that a perhaps evermore-rapacious neoliberalism engenders. For example, there is the current fad of young women, including some celebrities, virtually proclaiming that they do not need feminism. There is a popular, best-selling book that promotes the notion of “leaning in” to negotiate systemic oppression rather than trying to change it, and a host of other examples of postfeminism and overt antifeminism abound. All take up the neoliberal mantle of “personal responsibility.” And as the SlutWalk polemic over race indicates, the erasure of women who are not white, cis-gendered, and middle-class is extant within feminisms. We have much work to do.

Therefore, in the spirit of the riot grrrl practices of consciousness raising, creative resistance, and community building, I invite Lateral readers/viewers to engage in a dialogue about the productive potential of performing shamelessness to resist patriarchy, racism, and the violences of neoliberalism. Can or should shamelessness be reframed, reconstituted? How can young girls, and for that matter women of all ages, cis-gender and gender nonconforming, challenge the violences of patriarchy in ways that honor individual and collective experiences and do not recuperate other forms of structural oppression? What are you doing/what can we do to shamelesslessly resist neoliberal immiseration? What about your students? How can we help them resist? I invite you to weigh in and perhaps even create your own declarations or virtual performances of shameless feminist resistance.

At the risk of being (riot grrrl) clichéd, I double-dare ya.

My Confessional #1

I took up this practice as a teenager at my suburban high school as well as at punk shows. While I found writing “SLUT” across my chest or down my arm or across my stomach empowering, I was blind to the race and class privilege underscoring my use of gender deviance as resistance (I identify as a white queer cis-gender woman). It was only when I first encountered bell hooks’ work as a freshman undergraduate that I began to understand white privilege, class privilege, and intersectionality. I also failed to recognize that I had done nothing to overturn patriarchy, homophobia, racism, classism and was actually inadvertently supporting the status quo with my one-woman performance of sociocultural reappropriation. ↩

My Confessional #2

As problematic as the practice was, it provided me and many other young women with entry into feminism as action rather than just ideas, and it did counteract the queer-bashing and sexism that I encountered daily by improving my self-esteem and thus my willingness to take up space in the world. It also connected me with and eventually to other feminists, intersectionality, and more effective means of protesting structural inequality. With this confessional (as with the others), the problem of collapsing the personal and political, the private and public, in characteristic neoliberal form, remains, but I wonder, is it entirely problematic? What if young girls did not have this tactic of resistance? Without it, would I and other women of my generation be more interested in leaning in than in teaching to transgress? ↩

“White Boy”

There is arguably a direct line from Bikini Kill’s critique of slut-shaming nearly twenty years earlier in the song “White Boy.”

The song, which excoriates rape culture, misogyny, and idealized respectable, passive femininity with biting sarcasm, begins with a recording of a Hanna asking a young man why he thinks women ask for rape or sexual harassment:

Kathleen Hanna: How do they ask for it?

White Boy: the way they act, the way they… I… I can’t say they way they dress because that’s their own personal choice.

Some of these dumb hoes, those slut rocker bitches walking down the street,

they’re asking for it, they may deny it but it’s true.

***

Lay me spread eagle out on your hill, yeah

Then write a book bout how I wanted to die

Its hard to talk with your dick in my mouth

I will try to scream in pain a little nicer next time

WHITE BOY… DON’T LAUGH… DON’T CRY… JUST DIE!

I’m so sorry if I’m alienating some of you

Your whole fucking culture alienates me

I can not scream from pain down here on my knees

I’m so sorry that I think!

WHITE BOY… DON’T LAUGH… DON’T CRY… JUST DIE!

Bikini Kill, “White Boy” Lyrics Plyrics.com (accessed on August 12, 2014) <http://www.plyrics.com/lyrics/bikinikill/whiteboy.html>. ↩

My Confessional #3

A fellow “daughter of riot grrrl,” I view my academic labor as part of the legacy. While I am decades removed from the fiery rage that underscored my actions and activism as a teen and young adult, my feminist punk rock fist remains in the air in new but consistent ways. In 2010 I taught the 100-level undergraduate course “Women’s Voices Through Time” at American University, which non-WGSS students often took to fulfill a General Education requirement, i.e. most of the students were new to WGSS, new to feminism, and did not necessarily have any interest in the course outside of checking a Gen Ed off their list of requirements. I had my class of 40 students (39 cis-women and one gay-identified cis-man) read Sara Marcus’s then just published Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. I was nervous the day of the class discussion given my biased relationship to riot grrrl as my own beloved introduction to feminism; I worried that my students would not “get it,” and would be especially hostile to body writing /word reclamation and the “ugliness” many of us intentionally embraced to talk back to sexism. I worried that I would not give them enough space to form their own opinions. Also, after spending a great deal of time considering the pedagogical and punk rock implications of doing so, I managed to not show up to class with “SLUT” scrawled on my body. In short, I feared they would be hostile or at least dismissive of the thing that so poignantly changed my life and really made it possible for me to be standing at the front of that classroom, and I hoped they too might be galvanized. I was also curious about whether or not they would find riot grrrl to be effective, particularly in terms of body writing.

I was pleasantly surprised to see my racially mixed, international students thoughtfully evaluate and connect with the impetus and the practices. After the riot grrrl unit, I had groups create zines, which they all did with enthusiasm. And several white and nonwhite students chose to perform revisions of body writing in their final projects (they were required to do a final creative project that “said something” about women/women’s place in the world, in historical context). Sensitive to the polysemy of the signifier with riot grrrl body writing/word reclamation, one female student tweaked it: she invited young women to write onto their bodies words or names that they had been called, and to hold up signs stating their responses to the insults and labels used to shame and silence them. She did a photo shoot of this on the AU quad. She reported that she and the other women (whom she did not know prior but who had responded to her call for participants) felt empowered by the project, and no longer felt isolated or a/shamed of/by the sexist, racist, homophobic, size-ist things they had been called. The women at least for that moment were part of a collectivity and aware of the structural nature of sexism and racism. All smile broadly in the pictures.

To this viewer, that signifies a familiar and powerful feminist shamelessness that directly talked back to the politics of respectability in ways that were meaningful to each individual participant. This did not overturn the heteropatriarchal, racist violences of neoliberalism. But it broke silence around sexist oppressions and its languages; its dialectical critique is a start. ↩

[Editorial note: The article has been edited by the author to redact violent language in song titles.]

Notes

Notes

- Sara Marcus, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (New York: Harper Collins, 2010), 272. ↩

- Gayle Wald and Joanne Gottlieb, “Smells Like Teen Spirit: Riot Grrrls, Revolution, and Women in Independent Rock,” in Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture, eds. Andrew Ross and Tricia Ross (New York: Routledge, 1994), 266. ↩

- See John Fiske, Television Culture (New York: Routledge, 1987),and John Fiske, Power Plays, Power Works (New York: Verso, 1993). ↩

- Kevin Dunn and May Summer Farnsworth, “‘We Are the Revolution’: Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing,” Women’s Studies 41 (2012): 136. ↩

- Dunn and Farnsworth, “‘We Are the Revolution,’” 137. ↩

- Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (New York: Routledge, 1979); Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t no Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987); Fiona I. B. Ngo, “Punk in the Shadow of War,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 22.2–3 (July–November 2012): 203–232. ↩

- Wald and Gottlieb, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” 252. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The Punk Singer: A Film About Kathleen Hanna. Directed by Sini Anderson (New York: IFC Films, 2013). ↩

- Mary Celeste Kearney, “The Missing Links: Riot Grrrl—feminism—lesbian culture,” in Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender, ed. Sheila Whiteley (London: Routledge, 1997), 218. ↩

- Dick Hebdige, “Posing… Threats, Striking… Poses: Youth, Surveillance, and Display,” SubStance 37–38 (1983): 83. ↩

- Lauraine Leblanc, Pretty in Punk: Girls’ Gender Resistance in a Boys Subculture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2002). ↩

- See Wald and Gottlieb, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” 254, and Kirsten Schlit, “‘A Little Too Ironic’: The Appropriation and Packaging of Riot Grrrl Politics by Mainstream Female Musicians,”Popular Music and Society 26.1 (2003): 5-16. ↩

- Ngo, “Punk in the Shadow of War.” Patti Smith’s and the Avengers’ song titles are spelled out in each artist’s discography. ↩

- Fiona I. B. Ngo and Elizabeth A. Stinson, “Introduction: Threads and Omissions,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 22.2-3 (July-November 2012): 165. ↩

- Ngo, “Punk in the Shadow of War,” 204. ↩

- Mimi Thi Nguyen, “Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival,” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 22.2-3 (July-November 2012): 173-196. ↩

- Kearney, “The Missing Links,” 218. ↩

- Ibid., 223. ↩

- Ibid., 222. ↩

- Scholars have questioned the standard narrative of “waves” of US feminism, preferring instead a more complex and continuous history. For instance, see Dorothy Sue Cobble, Linda Gordon, and Astrid Henry, Feminism Unfinished: A Short, Surprising History of American Women’s Movements (New York: Liveright, 2014). ↩

- Ellen Riordan, “Commodified Agents and Empowered Girls: Consuming and Producing Feminism,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 25.3 (July 2005): 279. ↩

- Linda Gordon, “The New Feminist Scholarship on the Welfare State,” in Women, the State, and Welfare, ed. Linda Gordon (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 9-35, and Teresa L. Amott, “Black Women and AFDC: Making Entitlement Out of Necessity,” in Women, the State, and Welfare, ed. Linda Gordon (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 280-300. ↩

- For path-breaking examples of women-of-color critiques of marginalization within mainstream feminism and a call to consider intersectionality to correct this, see Gloria Anzaldua and Cherrie Moraga, eds., This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (Berkeley: Third Woman Press, 1981), and Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, “Race Reform, Retrenchment: Transformation and Legitimation in Anti-Discrimination Law,” Harvard Law Review 101.7 (1988): 1331-1387. ↩

- Riordan, “Commodified Agents and Empowered Girls,” 279-280. ↩

- Ibid., 281. ↩

- Marcus, Girls to the Front, 90. ↩

- Karen Orr Vered and Sal Humphreys, “Postfeminist Inflections in Television Studies,” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 28.2 (2014): 156, 159. ↩

- Ibid., 157. ↩

- Marcus, Girls to the Front, 40. ↩

- Natalie D. Smith, review of Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, by Sara Marcus, Affilia: Journal of Social Work and Women 27: 2 (2012): 227. ↩

- Marcus, Girls to the Front, 113-114. ↩

- Ngo and Stinson, “Introduction: Threads and Omissions,” 167. ↩

- Elizabeth A. Stinson, “Means of Detection: A Critical Archiving of Black Feminism and Punk Performance,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 22.2-3 (July-November 2012): 275-314. ↩

- Dunn and Farnsworth, “‘We Are the Revolution,’” 139. ↩

- The Punk Singer. ↩

- Rebecca Walker, To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism (New York, Anchor, 1995), xxxiii. ↩

- Kathleen Hanna, “On Language” (lecture, New York University, New York, NY, March 6, 2014). ↩

- Jenna Freedman, “Grrrl Zines in the Library,” Signs: Journal Of Women In Culture & Society 35.1 (September 2009): 52-59. ↩

- Marcus, Girls to the Front, 326. ↩

- Hanna, “On Language.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jennifer Bleyer, “Cut and Paste Revolution: Notes from the Girl Zine Explosion,” in Women’s Voices, Feminist Visions, 4th edition, eds. Susan M. Shaw and Janet Lee (New York: McGraw and Hill, 2009), 543. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Riordan, “Commodified Agents and Empowered Girls,” 288. ↩

- A. Wolfe, “Archiving Riot Grrrl’s Zine History,” Broken Pencil 46 (July 7, 2011): np, accessed July 16. 2014, http://www.brokenpencil.com/issue-46/grrrlblud. ↩

- Kristin Schilt, “‘I’ll Resist with Every Inch and Every Breath’: Girls and Zine Making as a Form of Resistance,” Youth and Society 35.1 (Sept. 2003): 71-97. ↩

- Alison Pipemeier, “Bad Girl, Good Girl: Zines Doing Feminism,” in Women’s Voices, Feminist Visions, 5th edition, eds. Susan M. Shaw and Janet Lee (New York: McGraw and Hill, 2012), 499. ↩

- Dunn and Farnsworth, “‘We Are the Revolution,’” 142-143, 146, 150. ↩

- Bleyer, “Cut and Paste Revolution,” 545-546. ↩

- Ibid., 546. ↩

- Hanna, “On Language.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Marcus, Girls to the Front, 147. ↩

- Wald and Gottlieb, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” 268. ↩

- Ibid., 267. ↩

- Marcus, Girls to the Front, 146. ↩

- Ibid., 147. ↩

- Angela McRobbie, The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture, and Social Change (New York: Sage, 2009). ↩

- Nguyen, “Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival,” 174. ↩

- Ibid., 174-175. ↩

- Jessica Rosenberg and Gitana Garofalo, “Riot Grrrl: Revolutions from Within,” Signs 23.3 (Spring 1998): 810. ↩

- Ibid., 825. ↩

- Ibid., 841. ↩

- Ibid., 815. ↩

- Ibid., 817. ↩

- Ibid., 820. ↩

- Ibid., 821. ↩

- Nguyen, “Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival,” 177-178. ↩