Since the millennium, there has been a growing global awareness about the business of human trafficking as it has exponentially expanded in relation to the neoliberal economic climate, the vast displacement of people through wars and conflict, and the growth of tourism and e-commerce. Because theatre and performance studies work through an epistemology of embodied practices and symbolic codification, it is an exemplary site for commenting on and contributing to public knowledge about the trafficking issue. Highly visible public issues, such as trafficking, typically generate and maintain coded and symbolic rules of appearance for the bodies they describe. As those who are trafficked are in reality mostly invisible, missing, and silent, this can be seen as a substantial contradiction that goes to the heart of performance: the absent presence of all representation, the governmentality of biopolitics with its categories and classifications, the actual person who remains unknown beyond the performances that make her intelligible.

Jenny Edkins, writing about missing persons, has made an important distinction between the what and the who of such persons. If the “what” is the already perceived, intelligible set of characteristics or markers that can be grasped by reason of the existing order, the “who” cannot be captured: “But the who is what is lost and what is absolutely irreplaceable when someone goes missing. It is not just that there is no one there, but that that particular unique being, that particular someone, is not there. And this is why missing people disturb administrative classifications.”1 I appreciate Edkins’ work not only for the reminder that all official statistics, laws, and institutional attention do not make visible the subjects of human trafficking, but also for emphasizing that the “who” emerges in a relationality that often exists beyond the regimes of public visibility.

Nevertheless, the effort to leverage justice for trafficked persons necessitates struggle in realms both visible and invisible, as attempts to legislate, criticize, or shape public policy operate in the visible and indeed bureaucratic domain, while attempts to address, heal, and recover from trauma may occur elsewhere. Performance scholars can contribute in both realms: providing (performance) analyses of scenarios and roles governing the business of trafficking, public policy, and the law can yield insights into how the politics of trafficking determine definition, exclusion, and prescribed behaviors. Examination of representations of trafficked victims and survivors reveals a performative dimension embedded in the repetition and sedimentation of familiar tropes as well as occasional glimpses of what is barely discernible. Performance practices are instrumental in therapeutic approaches to recovery, as both dance and theatre provide a relational context for survivors whether in private settings or in situations of public activism through art. However, each of these areas raises complex issues, well beyond my ability to fully address here. I will focus on the policy issues informing discussions of trafficking in several locations around the world (the US, Australia, and Europe primarily, followed by a focus on California) in order to show how matters of labor and exploitation play out in the trafficking scenarios in those regions. Because trafficking is deeply entwined with migrant labor and immigration control, it is an especially appropriate focus for examination at this time of heightened hostility to immigration and increasing awareness of trafficking. Other essays in this issue (Castillo, Noriega, Santana) describe and discuss in detail some representational strategies that have been created in theatrical performances, and Urmimala Sarkar Munsi describes how performance, specifically dance, can become a means of healing trauma. Together I hope our work can address both the visible and the elusive aspects of this issue and gesture to a program of further research appropriate to performance scholars who want to join the struggle to end trafficking.

In what follows, I’ll look first at problems of definition and legislation, then examine some of the divisions among feminists and activists concerning how best to respond to women trafficked for sexual exploitation. The status of trafficked women, both as victims and as survivors, will be described in terms of performance, from two aspects: the construction of the public face of these women “on stage,” and the private and often invisible predicaments they face behind the scenes. I’ll look at one organization that uses the arts to address recovery, and finally, I’ll suggest some ways that theatre and performance scholars can actively participate in efforts to end human trafficking and to help its survivors.

A Question of Counting

Consider the following two accounts:

The U.N. crime-fighting office said Tuesday that 2.4 million people across the globe are victims of human trafficking at any one time, and 80 percent of them are being exploited as sexual slaves….$32 billion is being earned every year by unscrupulous criminals running human trafficking networks, and two out of every three victims are women.2

The International Labour Organisation [ILO] estimated in 2012 that 18.7 million people are exploited in the private economy, by individuals or enterprises. Of these, 4.5 million (22 per cent) are victims of forced sexual exploitation, 98% of whom are women.3 Human trafficking has been estimated to generate 150 billion dollars a year, two-thirds of which is income from human trafficking.4

The United Nations and the ILO are the most authoritative sources of global data on this topic, because they are international in scope and data management, and presumed to be “objective.”5 Even so, one can hardly reconcile the two sets of statistics I have reported above. The UN and the ILO do not agree on the total number of persons trafficked, nor how much of it is sexual exploitation, nor even the number of women involved, since 98% of the ILO’s 4.5 million estimate would still be nearing double the count of total trafficked according to the UN. How are we to grasp the problem?

First, looking more closely at these resources, the UN figures came from a 2012 briefing at a special meeting on trafficking at the General Assembly by Yuri Fedotov, the head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, who was quoted by an AP reporter, who, we can conjecture, might have misquoted him. Alternatively, although this meeting was held in 2012, perhaps the 2.4 figure came from the 2008 “Fact Sheet” of UN.GIFT (Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking), which estimates 2.5 million people are in forced labor, 43% are victims of sexual exploitation, of whom 98% are women and girls. However, it turns out that the UN source for these figures is actually the International Labour Organization figures from 2007,6 revised by the ILO in 2012 based on a more robust methodology as described in their report. Even so, 43% of 2.5 million people would not come close to the ILO revised figures of 4.5 million victims of sexual exploitation.

This confusing and circular investigation of the data is typical of attempts to quantify and describe the scope of the human trafficking problem worldwide.7 There are at least three good reasons why it is difficult to collect and verify this data. First, the characteristics of trafficking include that it is an underground practice, often unreported, and outside normal channels of demographic data. Second, the differences in legislation covering trafficking across nation states are substantial, and moreover most victims have only a weak legal status in most countries under these laws, often caught between their countries of origin and the country to which they were trafficked—they are virtually stateless in this circumstance. Third, the absence of comparable cross-nation statistics of reported crimes, indictments, and court cases means there is no global database. Also missing is comprehensive data on organized efforts at support, treatment, and survivor outcomes.8

The instability and incommensurability of data across the globe creates serious problems for the coordination of efforts to combat trafficking and also creates a political weakness in the case that trafficking is an important problem needing public attention. Some readers may be thinking that the ability to accurately survey the scope of the problem may not be so critical since the numbers are high and rising in most accounts: “So who cares how many precisely—there’s enough to demand a response!” However, this is not always a persuasive view, as we shall detail below. (A self-reflexive observation: in order to indicate the approximate scope of some aspects, I will myself quote statistics below, sometimes without comment—even having made the argument about their unreliability.) The double-bind is that to persuade and inform, one needs to say some concrete things about these issues, while knowing full well that any one statistic might be challenged. In order to see how this issue comes back to haunt anti-traffickers, it is necessary to consider one other factor: the definition of terms as they have come to be accepted internationally.

The agreement on a definition of human trafficking that can be accepted across the world was concluded in 2000 when the United Nations General Assembly adopted the “United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children.” It defines trafficking as:

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, or fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.9 [Emphasis mine.]

In negotiating among many states, organizations, and NGOs to develop this definition, a number of ideological struggles came into play, chiefly focused on the phrase, “exploitation of the prostitution of others.” This phrase is ambiguous as to its exact meaning because it represents a compromise following extensive disagreement over whether the protocol should cover only forced prostitution or all prostitution. Questions of consent and coercion were at the heart of this distinction, and particular nations and international organizations such as the “Coalition Against Trafficking in Women” (CATW) lobbied to have the protocol include opposition to legalizing prostitution.10 Disputes over the legitimacy of prostitution almost prevented the convention from passing, but this compromise language allowed it to pass, and as of 2016, 117 UN member states have signed the protocol and 169 are parties to it, consolidating it as the internationally-authorized definition.

The policy debates within different nation-states over human trafficking legislation and programs are marked by these divisions between different groups of actors. In the United States, for example, the anti-trafficking lobby is often made up of coalitions of feminists and evangelical Christians.11 During the Bush presidency they were a strong political pressure group, responsible for shaping language in several important bills, including the “Trafficking Victims Protection Act” (TVPRA), the federal anti-trafficking law in the United States. They tend to be moralistic about the evils of sex work and abolitionist in terms of policy and law—meaning they see prostitution as correctly illegal and consider trafficking a problem growing out of prostitution. On the other side, sex worker groups and feminists of a more libertarian persuasion oppose the harsher penalties for prostitution sought by this lobby, and attempt to downplay the seriousness of the trafficking problem by pointing out the unreliability of the numbers, and the intrusion of the government into the lives of its citizens. They have gained ballast in recent years after 9/11 by complaining about heightened surveillance of individuals and the management of trafficking under the Department of Homeland Security, the defense body that targets terrorism. The irony is that the welfare of trafficked women and children is compromised by the political differences among groups who might be thought of as natural allies. So, why do scholars and activists who proclaim themselves to be Left or feminist try to thwart government’s efforts to intervene in trafficking to identify and protect victims?

The Sex and Labor Question

At the heart of the matter is the disagreement about considering sex as work, and whether or not prostitution harms all sex workers. Perhaps more broadly, it is a dispute over whether harm is implicit in the exchange of sex for money. In countries such as the US where prostitution is illegal, many anti-trafficking activist groups are “abolitionists,” a term used to indicate an anti-prostitution stance against either legalizing sex work or granting employment protections and recognition to sex workers—note the rhetorical connection to the early abolitionist movement against slavery in the nineteenth century. The use of slavery language to describe forced labor effectively hearkens back to the global slave trade and has particular resonances for countries like the US with specific histories of institutionalized slavery.

In other countries such as Australia, where sex work is legal in parts of the country, some anti-trafficking activists sharply distinguish sex work from the forced labor of trafficking. Organized sex workers in both countries are often against anti-trafficking measures because of the impact on their efforts to secure work-related rights and benefits. For example, Janelle Fawkes, the CEO of Australia’s Scarlet Alliance, an organization that represents and supports sex workers, points out that policy discussions referring to the sex industry are now always linked to the trafficking issue:

[The s]ex industry law reform discussion is no longer about the occupational health and safety of sex workers. It’s no longer about incentives to comply. It’s no longer about increasing safety or looking at the real issues for sex workers. It’s now about this perceived set of [trafficking] issues.12

The term “perceived” signals the argument that the numbers associated with trafficking have been inflated and that it might not be a large social problem but rather a “moral panic,” and, like the nineteenth century fear of so-called “white slavery,” largely imagined. Not that all sex workers deny the exploitation of trafficking. It is more complex—seeing their own labor issues displaced in legislative and policy debates, sex workers understandably try to re-center advocacy of their own reforms. In The Politics of Sex Trafficking; A Moral Geography, the Australian authors (who are feminists) illustrate the force of argumentation concerning these issues contrasting the US to their own context.13 Erin O’Brien, Sharon Hayes, and Belinda Carpenter argue that “abolitionist” coalitions of right-wing religious groups and feminists have linked sex work and trafficking together in ways that have hurt sex workers’ struggles for employment recognition and protection. They also rely on the charge that statistics are inflated, and that only worst case scenario stories (narratives) are published and stressed in the media and in lobbying the government. There is also an argument that poor women and women from developing countries are not accorded the respect of acknowledging the possibility of agency and choice on their part, and so are discriminated against. Legalization of sex work, and regulating it to protect its workers is the more important activism, and ultimately more effective against trafficking as well, from this point of view.

However, there is some evidence that trafficking increases when prostitution is legalized, although it is contested and not conclusive.14 A 2012 empirical study by German and British economists looked at 150 countries to assess whether legalizing prostitution increases human trafficking. They identify two competing theories: the “scale” effect holds that legalizing prostitution leads to an expansion of the prostitution market and thus an increase in human trafficking; the “substitution” effect holds that domestic workers will fill the demand in place of trafficked persons when domestic workers can work legally and are protected under the law. The results of their study, however, indicate that the scale effect is the stronger: “Our quantitative empirical analysis for a cross-section of up to 150 countries shows that the scale effect dominates the substitution effect. On average, countries with legalized prostitution experience a larger degree of reported human trafficking inflows.”15 The researchers are cautious about this result, calling for more research and lamenting “the clandestine nature of both the prostitution and trafficking markets” (which makes the data base somewhat unreliable). Moreover, when you separate the low income countries from the high, “the effect of legal prostitution is no longer significant.” And democracies have a 13.4% points higher probability of receiving high reported inflows. At best, we might consider these results a snapshot of the situation pre-2012, and most notably strongest with respect to high-income democracies with already high demand (US, Europe, and select others).

In other countries, some laws and policies are now targeting the consumer, following the “Nordic solution” which bans prostitution but prosecutes its customers rather than sex workers (notably in Sweden). While this approach improves the legal treatment of some sex workers, it also attempts to interfere with and shut down the trade itself, and many sex workers still oppose this. However, from the point of view of countries such as the US, Australia, and other democratic countries with high levels of income, targeting the customers has a special suitability to contesting trafficking since the exploited are mostly women and children from the developing world while the consumers are often first-world men. According to some accounts, only 10% of all trafficked people worldwide come from industrialized nations yet 50% of worldwide profits are made in industrialized nations. Asian countries have the highest total number of persons trafficked for sex, but Europe is the top destination for traffickers, and the US is one of the ten countries identified as having the most profits.16 Thus in terms of redressing the problem, a number of activists, not all of whom are abolitionists, support the prosecution of consumers of services from trafficked people as it targets the male privilege of first-world individuals who tend not to see themselves as contributing to a problem like trafficking, in spite of their implication within it. Longitudinal research of the impact of this approach will be needed to provide more conclusive proof of its effects on demand for the sex industry.

The human trafficking predicament becomes further complicated when we turn to issues of migrant labor in this time of global flows. Women are heavily affected by the flexibilization of low-wage labor in service and informal economies such as domestic, care, and sex sectors. As Rutvica Andrijasevic writes in Migration, Agency and Citizenship in Sex Trafficking (2010), “The demand for low-wage labour in the service sector, which is both gendered and racialized, encourages women’s migration and represents an alternative economic global circuit.”17 However, the benefits of such cross-border mobilization are not equally distributed. The condition of undocumented migrants was worsened when the Netherlands became the first EU country to legalize prostitution (in 2000). While the Dutch parliament acknowledged prostitution as a commercial activity subject to the same labor regulations and occupational guidelines as any other sector, undocumented migrant sex workers were not entitled to any of the new rights or protections. Andrijasevic points out: “In legalizing the work of EU nationals while keeping the work of non-EU nationals illegal, the sex sector followed the larger pattern of opening up markets and labour in Europe to the EU citizens and severely restricting the labour mobility of non-EU citizens.”18 In addition, Andrijasevic, puts yet another spin on this situation—she regrets the discouragement of eastern European women from making the cross-border journey, not as trafficked women, but as women who might seek their own advancement. She argues that anti-trafficking campaigns “equate women’s informal labour migration with forced prostitution and indirectly encourage women to stay at home.”19 According to her, this reinforces traditional notions of womanhood, the gendered division of labor, and consolidates the old exclusions of women from the world outside the home.

In concluding this part of our discussion, I would emphasize that the tensions that cut across the analyses of this issue are three-fold: first, the ideological battle over prostitution/sex work divides women against themselves, and contains the historical baggage of puritanism, but also the neoliberal baggage of entrepreneurialism and individual choice. Second, the argument over statistical accuracy can be used by either side to further their positions, but is most often used to undercut advocacy that draws attention to a wide-spread and growing problem by denying or minimizing it. Third, the issue of coercion emerges as a troubling knot of undecidability. For the abolitionists, all sex work is coercive since no woman would choose this demeaning practice. For others, choice is relative to other available options. Coercion, still others argue, may be present even in cases where persons seemingly give consent, or are coerced when they realize that consent entails forced labor and often violence. In order to decide the adequacy/inadequacy of these interpretations, the statistics and categories of governmentality will not provide answers: what is needed are the elusive and mostly invisible lives of real persons who have been trafficked. For these insights, we must turn to local scale narratives, ethnographies, interviews, and self-disclosure. Some of our evidence will by its nature be anecdotal and partial, but nevertheless powerful and persuasive.

From Macro to Micro: Focus on Local Immigration and Law Enforcement

Beyond the large NGOs that work nationally and internationally to educate the public and their legislators about human trafficking (such as CATW or the Polaris Project), there are a large number of smaller organizations working locally or regionally. I turn now to northern California, where I live, and to what I have learned about trafficking within the state and my particular location in the bay area. Gena Castro Rodriguez is the Head of Victim’s Services for the City of San Francisco, and a source of reliable information for the region. In a public presentation in January 2015,20 she identified California as a major site of trafficking within the US, and reported that the trafficked here are overwhelmingly young, often between fourteen and sixteen years old. She said about 85% have experienced child abuse or incest before they were trafficked; 80% come originally from other countries, and speak 41 languages. Her office is directly tied to the District Attorney’s office—in fact, she works for the current DA, George Gascón. I began to understand that getting support services in California almost always involves law enforcement.

Women are trafficked in California in a variety of ways. A number of young women are recruited by traffickers when they run away from abusive families or other family difficulties and are living on the streets. Others are seduced by older men who become “boyfriends” and leave home to follow them, eventually finding themselves sold into sex work and unable to leave. Women who have been trafficked from Mexico or other countries are often brought to California by members of their family or the family’s associates. All of these circumstances complicate the issues of coercion and consent in the legal definitions of trafficking, and can complicate motivations to leave the forced labor situation, and also to prosecute the traffickers.

In her briefing, Rodriguez spoke about a special kind of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that survivors of trafficking undergo.21 She connected the experiences of trafficked women to a chain of abuse in their lives. “Trafficked persons, especially those sexually exploited, usually have repeated and overlapping experiences of trauma, sometimes for years, which need unique and specific approaches to healing.” This disorder does not follow the etiology of soldiers with PTSD, who often have a circumscribed period of trauma which comes to an end. This helps to explain why many times trafficking victims will return to their abusers. Survivors need sustained support to recover from this kind of PTSD.

Shortly after hearing Rodriguez, I went to the Asian Women’s Shelter (AWS) to meet Hediana Utarti, the community projects director. The Asian Women’s Shelter is one of the oldest agencies of its kind in San Francisco. It started in 1988 as a domestic violence shelter and at the time one of only three nation-wide that provided language services for Asian women. Over the years, trafficking victims have also become part of its mission. AWS helps between eighty and one hundred clients a year. Sometimes women come with their children and stay at the “safe house” for as long as nine months or a year. Utarti commented that a number of clients return to their former lives, and explains that she has followed some clients over a number of years. The agency provides shelter in a secret location, runs a crisis line, takes clients to get medical treatments, translates, interprets in court or in police situations, arranges therapy, and a variety of other healing practices—what is called “case management” in the field of social services. They have a small full and part-time staff, and eighteen volunteer staff speak fourteen languages.

The AWS describes itself as “survivor centered.” This has implications for the way they operate and how they approach their work. Alive to all the nuances and entailments of language, Utarti told me that at AWS they do not claim to “save” or “rescue” their clients; they “assist” them. They do use the language of victimization and exploitation, but also of agency and choice. The goal is to acknowledge the full personhood of the survivor, recognizing both the victimized aspects of their experiences but also their full human abilities to develop and implement their own plans for safety, care, and action. Utarti said that when clients are too afraid to press charges or decide not to because of ties to family members who trafficked them (not an uncommon scenario), her staff accepts these decisions as the client’s choice. She told me of one young girl who was trafficked from Mexico to Los Angeles by a relative. She lived as a sex worker for several years, suffering abuse and violence and fearing for her life. However, during this time, she was part of a closely knit group of tightly controlled girls, and became a member of a gang. She finally managed to escape and came to San Francisco, to the AWS. She cooperated with law enforcement in bringing charges against her traffickers, and was relocated and supported in her recovery. However, she was terribly lonely, missing Los Angeles, friends, and family. She knew if she went back, she would put her life in danger of retaliation, but after a long period in the north, she decided to return. Utarti said it was very painful to see her make this decision, and she did everything she could to advise against it and to provide all the support AWS could offer. Finally, however, she had to accept the girl’s decision. This example was offered as a glimpse into the realities of the difficulties of survivors and the “two-steps-forward, one-step-back” dance of providing hands-on help to trafficking victims (cf. Estrada Fuentes’ interview with Sohini Chakraborty for comparison to India).

In speaking with Utarti, I learned about other agencies in San Francisco working with trafficking clients. She told me, for example, about city-wide efforts to develop some special programs for trans youth because they are particularly susceptible to abuse and violence (this conversation occurring as trans rights was becoming a visible national issue, and one year before the North Carolina “Bathroom law” ignited public debate in spring 2016 ).22 Huckleberry House serves a large LGBT population in San Francisco, large because young people often run away from their abusive situations to seek a new life in supposedly liberal San Francisco. St. James Infirmary was started in 1999 as an occupational health and safety clinic for sex workers, and is named after Margo St. James, the San Francisco sex worker who founded COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), the first labor organization for sex workers in San Francisco in 1973. It is now also a resource for trafficked persons providing legal aid, mental health services, and support groups as well as medical services. (Importantly, it also demonstrates that supporters of sex workers can also support trafficking survivors without ideological contradictions.)

In the city of San Francisco, the police department and the judicial system through the District Attorney’s office are implicated in most efforts to provide support services to victims. The Asian Women’s Shelter gets most of its referrals from the Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach group—and they work closely with the DA’s office and the San Francisco Police Department. Often clients first approach legal aid organizations for help rather than law enforcement or other agencies, when, for example, it is a question of whether or not they can be protected under the law. It is almost impossible for a trafficking client to get help without becoming involved in the legal and law enforcement agencies of the state. Even in the shelters, the law requires reporting of clients. To get T-visas, special visas giving trafficked persons permission to stay in the US, cooperation with the District Attorney’s office is required. For many, this is a frightening connection, one that may discourage them from seeking assistance. In addition, many anecdotal tales circulate of people taken into custody by the police in a raid, and then deported back to their country of origin whether this is safe for these victims or not. No wonder clients are afraid to come forward and ask for help if they may be imprisoned and deported.

The San Francisco Police Department has a stated policy of not arresting prostitutes (although prostitution is against the law), but does take people into custody when involved in a raid or other anti-trafficking operations. Sage, a survivor services NGO in San Francisco, now defunct,23 had successfully worked with the police department to train officers to take women into custody without using hand cuffs or referring to them as prostitutes. This accomplishment remains in place according to the District Attorney George Gascón.24 It is difficult to know whether to see San Francisco law enforcement as exceptional or standard practice, or whether officers really follow this protocol. In the past year, the SF police department has suffered two texting scandals in which officers have been revealed texting racist, sexist, and homophobic remarks to each other, and just as I was finishing this article, two San Francisco police officers were under investigation for possible connections to a (neighboring) Oakland Police Department sex trafficking scandal.25 Certainly elsewhere, the relationships between police and sex workers, including the trafficked, have been documented as hostile and violent. In a New York survey conducted by the Sex Workers Project, 30% of sex workers interviewed who worked on the street told researchers that they had been threatened with violence by police officers, while 27% actually experienced violence at the hands of police. In a similar survey, for those working indoors, 14% of sex workers reported police had been violent toward them, and 16% reported police initiated a sexual interaction.26

The Role of the Arts

I asked Hediana Utarti whether AWS used any performance-based activities as part of their support programs with clients, and told her about Sanved, the dance movement therapy program in Kolkata, described elsewhere in this issue (see Sarkar Munsi’s essay, and the Chakraborty interview, Estrada-Fuentes’s journal, and the annotated Sanved presentation in the “Appendix.”) She said they had nothing formal, but that sometimes in the evenings, after long days with lawyers, or in court, or at medical clinics, she and the clients staying at the shelter put on music and danced, or “some of them may simply move. It feels good, for the girls and for me too,” she smiled.

Some months later and closer to home, I became aware of ARM of Care, a small NGO that works specifically with art-based programs to help women and girls who are survivors of violence and trafficking. In Contra Costa County where I live, the community has only recently begun to be aware of local trafficking. Largely occupied by an upper-middle class population living in a prosperous bedroom community, it has not been a highly visible space of trafficking. However, according to Contra Costa County Prosecutor Nancy Georgiou “since January 2011, the problem of trafficking started to become more and more obvious. In 2011 she had four cases to review, and in 2013, thirty-two cases.”27 In 2015, in the neighboring city of Danville, police broke up a trafficking ring of three people who had been capturing women, raping them, and forcing them into prostitution for over fourteen years.28

ARM of Care was founded in 2012 by Amy Lynch. The organization operates without state support, and funds its work through donations and grants. They offer programs to other social service agencies working with sexually exploited youth, or are approached by the agencies to partner. Typically, the agencies do not pay ARM of Care: sometimes an agency will submit a grant proposal with ARM written into the proposal—this has happened three times, but none of them were successful. The acronym ARM stands for art, recreation, and movement, the main strategies employed by the organization to address “healing, restoration and empowerment to those who have experienced trauma.”29 To date, they have worked with eight different agencies who work with sexually exploited youth. Some of these are faith-based and while ARM of Care is not affiliated to any religious group or denomination, they are faith-friendly, and employ religious elements within some of their programs (example below).

Lynch has degrees in Somatic Movement Education and Recreational Therapy, and has worked for over thirty years with these skills serving a variety of populations.30 The staff also consists of a theatre specialist, a visual arts specialist, and a director of administration. Lynch and her small band have started their grass-rooted organization with the support of a local Board of Directors made up of concerned citizens, educators, and professionals. The slideshow ARM uses to educate public groups provides examples of several of the projects they have designed for clients, including “body mapping,” sewing and crafts, movement workshops, and cultural events for which tickets have been donated.

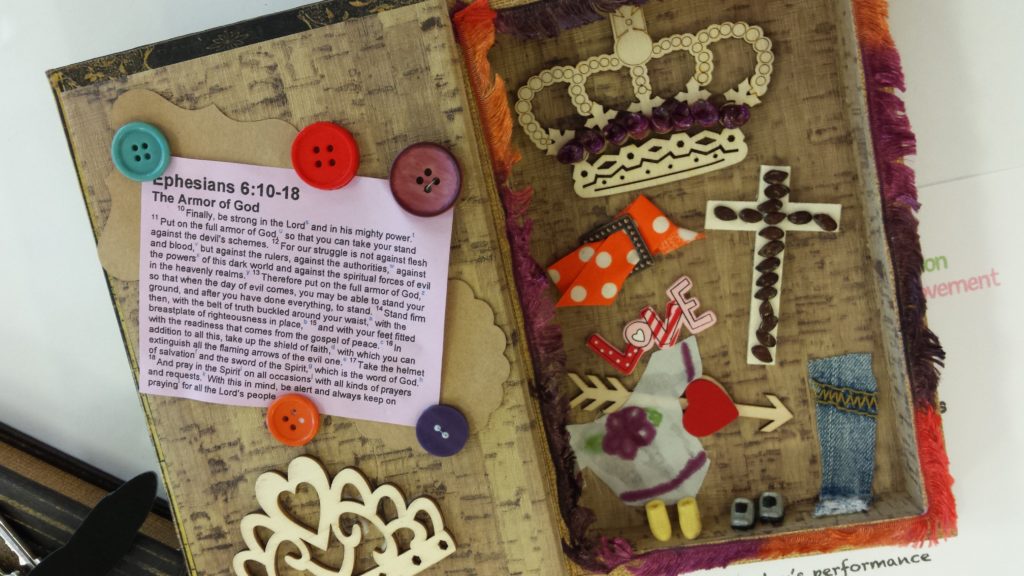

In one extended project, ARM took eighteen young clients to a local theatre production of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.31 Before the performance, staff conducted a workshop based on a bible text (Ephesians 6:10-18) that counsels, in part, “Therefore put on the full armor of God, so that when the day of evil comes, you may be able to stand your ground, and after you have done everything, to stand. Stand firm then, with the belt of truth buckled around your waist, with the breastplate of righteousness in place, and with your feet fitted with the readiness that comes from the gospel of peace.”32 Staff led movement exercises connecting some symbols from this text used by characters in the play to protect themselves and the young women’s own bodies. In a follow-up art module, they were asked to design their own wardrobes in response to the prompt, “What do you wear, or put on, every morning to prepare for the day?”

After the play, they discussed the performance over lunch, and at the end of the day, they each received a gift bag with a copy of the original book, a stuffed lion, and some Turkish delight (which features in the novel/play). This kind of project is tailored for the particular population of survivors that ARM is working with, depending on the organization it supports, and the ages and situations of the clients.

Although this example and other projects ARM carries out may seem very simple and concrete, ARM does an excellent job of explaining the links between creativity and healing. For example, a recent newsletter (July 2016), describes this connection:

We also provided a program [. . .] on what it felt like to be a woman. The girls did a brain map where they shared words of qualities and experiences. Our movements connected with our bodies and femininity, and then they drew about what they were thinking and feeling. One of the women arrived that morning at this facility for the first time in the middle of the program. She sat down with us in time to do the movement exercise and draw with us. To be in a new environment and out of reach of her perpetrator was relieving for her, but being in a place where you don’t know anyone was also scary. Trauma has been part of what she has known for way too long. What she shared of her story through her words and drawing rattled us.33

On that first day of being rescued, she drew a picture of herself with a patch of yellow and a huge hand (see http://armofcare.net/anablepo/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ARM-of-Care-Newsletter_3.1-Summer-2016.pdf). The newsletter notes of the image, “The yellow at the bottom is her child, which she shared is the only bright spot in her life. The hand is of her pimp who had control over her body.” Two weeks later, after she had participated in group dance, she was able to say, “The parts of me that I negatively associate with from my trafficking experience now move, and I see it as freedom to move and to use those parts for freedom. For me to use my body for ME and NOT on demand for someone else.”34

Slowly, the elusive subject, the missing person, the trafficked survivor begins to emerge from a compilation of what we can learn about the big picture and from the embodied lived experiences of victims/survivors. The constraints on self-representation are formidable, and any representations by others must be ethical and protective of their identities and vulnerabilities. I began with Jenny Edkins emphasizing that the “who” emerges in a relationality which often exists beyond the regimes of public visibility, and have tried to traverse the geography of the “what” while providing glimpses into the “who.” ARM gives a glimpse into the relationality that can exist in situations of support and therapeutic practices. To conclude, I turn to a formal performance designed for the public sphere which features self-representation in an effective attempt to educate and to activate others.

In 2012, Proposition 35 on the California state ballot called for strengthening California laws against trafficking in the following seven ways:

- Higher prison terms for human traffickers

- Convicted human traffickers would be required to register as sex offenders

- Registered sex offenders would be required to disclose their internet accounts to authorities

- Fines would be increased from traffickers and used to pay for victims’ services

- Mandatory human trafficking training for law enforcement officers

- Strengthened victim protection in court proceedings

- Removal of the requirement to prove force to prosecute child sex traffickers.35

As part of the campaign in favor of Prop 35, an NGO in San Diego, California Against Slavery, produced a series of short videos of “Survivors’ Stories” available on their website and on YouTube.com. These solo performances are just over 2 minutes long. Please view the two stories below before continuing with the reading:

There are many issues involved in publicly exposing trafficking survivors in such a manner: Identifying the person by image and name is the first danger. Voyeurism and consumption of their stories as commodities from the safe space of the computer screen is a second. Re-activating trauma by repeating it is a third. In the case of these particular videos, the physical and emotional threats are somewhat—but not, I think, completely—assuaged by the circumstances: the subjects appear to be recovered women who have agreed to make the videos and disclose themselves. The stories are frank but relatively free of melodrama or other inappropriate affect. The narratives can help people understand how coercion and consent are not unambiguous legal or ethical categories by providing situated experiences. The videos capture agency and activism in the making: these survivors are fighting back as strong women supporting a legal ballot proposition that will improve the lives of others who are being trafficked. They thus model the ability to survive, and indeed to flourish, and to join the political struggle to end trafficking. The ballot proposition passed by 83% of the California electorate and is now law, except for the provision on disclosure of internet accounts, which has been challenged in federal court and found unconstitutional because of violation of free speech rights. This decision is now under appeal, and the rest of the bill’s provisions are being implemented.36

This essay has been dedicated to describing the complexities of the human trafficking phenomenon as it impacts victim/survivors and also the public. I have used a performance studies lens to suggest ways we theatre and performance scholars might contribute to anti-trafficking activism by employing our analytic skills to assess the public discourse around trafficking, and to critique hegemonic distinctions between, for example, coercion and choice. We can also analyze representations of the plight of trafficked victims in public spaces and on media to extend the search for more complex narratives and characterization than currently dominate those spaces. We can analyze and also create performances to see what new imaginaries might be able to evoke survivors’ lives and the appropriate ways of enhancing them, leveraging justice in a modest way in our scholarship, artistry, and activism.37

Notes

- Jenny Edkins, “Temporality, Politics, and Performance: Missing, Displaced, Disappeared,” in The Grammar of Politics and Performance, ed. Shirin Rai and Janelle Reinelt (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 145. ↩

- Associated Press (AP), “U.N.: 2.4 million human trafficking victims,” USA Today, April 3, 2012, accessed July 12, 2016, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/world/story/2012-04-03/human-trafficking-sex-UN/53982026/1. ↩

- International Labour Organization, “2012 Global Estimate of Forced Labour,” accessed July 12, 2016, http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/publications/WCMS_181953/lang–en/index.htm. ↩

- The International Labour Office, “Profits from Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour,” 2014, accessed July 12, 2016, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_243027.pdf. This report presents an increase over the 2005 estimate of $32 billion. ↩

- A third significant source is the annual report of the US State Department, the “Trafficking in Persons Report.” US Department of State, “Trafficking in Persons Report,” July 2015, accessed July 14, 2016, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/245365.pdf. While it does not specifically present a quantification of the problem, it does provide an annual ranking of countries of the world based on their efforts to meet the goals of the UN Protocol. I have not emphasized it because, being a nation-based resource, it is considered by some others outside the US to be an arm of US imperialism. I have cited it below in note 8, where useful illustrations or supporting information might apply. ↩

- UN.GIFT (Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking), “Human Trafficking: The Facts,” 2008, accessed July 13, 2016 https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/labour/Forced_labour/HUMAN_TRAFFICKING_-_THE_FACTS_-_final.pdf. ↩

- For a good sample of research specifically in the area of evaluating data collection with respect to human trafficking, see Ernesto U. Savona and Sonia Stefanizzi, ed. Measuring Human Trafficking: Complexities and Pitfalls (New York: Springer, 2007). ↩

- The US Department of State’s “Trafficking in Persons Report” comes closest to a global data base. The 2015 version uses the ILO figure of 32 million but does not give a figure or percentage for numbers trafficked for sexual exploitation. Different annual reports highlight a different dimension: in 2015 the report emphasizes the place of trafficking in the global labor supply chain, and singles out extractive industries such as mining to highlight the special connection to sex trafficking. Not only are the miners themselves often trafficked, but women are then provided to them in remote locations for sex: “Sex trafficking related to extractive industries often occurs with impunity. Areas where extraction activities occur may be difficult to access and lack meaningful government presence. Information on victim identification and law enforcement efforts in mining areas can be difficult to obtain or verify. Convictions for sex trafficking related to the extractive industries were lacking in 2014, despite the widespread scope of the problem.” US Department of State, “Trafficking in Persons Report,” 19. ↩

- The text of the protocol can be found under its full name: United Nations, “United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime,” article 3(a), 2000, accessed July 12, 2016, http://www.osce.org/odihr/19223?download=true. ↩

- CATW is one of the oldest and most powerful international organizations involved in the anti-trafficking movement. It is also one of the strongest “abolitionist” groups. This is clear from its current homepage which features three leading stories attacking efforts to decriminalize prostitution. See http://www.catwinternational.org, accessed July 14, 2016. ↩

- For example, Concerned Women for America and the National Association of Evangelicals. ↩

- Quoted in Erin O’Brien, Sharon Hayes, and Belinda Carpenter, The Politics of Sex Trafficking: A Moral Geography (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 8-9. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Seo-Young Cho, Axel Dreher, and Eric Neumayer, “Does Legalized Prostitution Increase Human Trafficking?” World Development 41 (2013): 67-82. ↩

- Ibid., 75-76. ↩

- Siddharth Kara, Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), location 555, Kindle edition. ↩

- Rutvica Andrijasevic, Migration, Agency and Citizenship in Sex Trafficking (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 6. ↩

- Ibid., 2. ↩

- Ibid., 9. ↩

- She was keynote speaker at the conference, “Out of the Darkness: Awareness, Protection and Services for Victims of Human Trafficking,” sponsored by the San Francisco Mental Health Education Funds (SFHEF). ↩

- See interview with Sohini Chakraborty in this issue for more on the use of Dance Movement Therapy (DMT) in the treatment of PTSD in survivors of sex-trafficking, among other at-risk communities. ↩

- Joe Sterling, Eliott C. McLaughlin, and Joshua Berlinger, “North Carolina, U.S., Square off over Transgender Rights,” CNN, May 10, 2015, accessed July 18, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/09/politics/north-carolina-hb2-justice-department-deadline. ↩

- Sage was the first anti-trafficking service organization I visited when beginning to research this topic in summer of 2013. The program manager Jadma Noronha told me about the police training, and also several other important projects including a “Nordic” style John’s School for first offenders, who could attend a session in lieu of prosecution, and an “Early Intervention Prostitution Program” designed to help individuals design and develop plans to “exit the criminal justice system.” When I returned a year later, the organization had more or less closed because of fiscal problems—one of the difficult things about small, on the ground programs—they too are fragile, just like their clients but in a different realm. ↩

- Gascón spoke at the “Out of the Darkness” conference cited above. ↩

- Jonah Owen Lamb, “SF Police Investigating Second Officer for Link to Oakland Sex Trafficking Scandal,” San Francisco Examiner, July 15, 2016, accessed July 18, 2016, http://www.sfexaminer.com/sf-police-investigating-second-officer-link-oakland-sex-trafficking-scandal/. ↩

- This research is published by the Sex Workers Project in two reports: “Revolving Door: An Analysis of Street-Based Prostitution in New York City,” 2003, accessed July 17, 2016, http://sexworkersproject.org/downloads/RevolvingDoorFS.html; and “Behind Closed Doors: An Analysis of In-door Sex Work in New York City,” 2005, accessed July 17, 2016, http://sexworkersproject.org/downloads/BehindClosedDoorsFS.html. See also a more recent report critical of using raids as a tool against human trafficking, “The Use of Raids to Fight Trafficking in Persons,” 2009, accessed July 17, 2016, http://sexworkersproject.org/publications/reports/raids-and-trafficking/. ↩

- Darya Esipova, “DA Says Human Trafficking Exists in Contra Costa County,” The Martinez News Gazette, January 19, 2014, accessed July 17, 2016, http://martinezgazette.com/archives/11146. ↩

- Gary Peterson, “Human Trafficking Ring Busted in Danville,” The Mercury News, August 26, 2015, accessed July 18, 2016, http://www.mercurynews.com/my-town/ci_28701211/danville-human-trafficking-ring-busted. ↩

- ARM of Care website, accessed July 18, 2016, http://armofcare.net/about. ↩

- Lynch works part time for the Juvenile Hall in Contra Costa County, a maximum-security detention facility for juvenile offenders up to age eighteen. She said an estimated 20% of their charges have been sexually exploited, and that the foster care system in California had 40-80% rates of juvenile sexual exploitation. Also corroborated by a 2012 study reported in the US Department of Health and Human Services Children’s Bureau’s, “Human Welfare and Human Trafficking Brief,” July 2015, accessed July 18, 2016, https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/trafficking.pdf. ↩

- A children’s fantasy novel by C.S. Lewis (1950) that has been fashioned into a successful play for the theatre and television by a number of adapters, and into a Disney film in 2005. ↩

- Holy Bible, New International Version, accessed July 18, 2016, https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Ephesians%206:10-18. ↩

- ARM of Care Newsletter 3 (Summer 2016): 6, accessed July 18, 2016, http://armofcare.net/anablepo/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ARM-of-Care-Newsletter_3.1-Summer-2016.pdf. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- For the details of the bill, see an analysis and summary: Attorney General of California, “Proposition 35: Human Trafficking. Penalties. Initiative Statute.,” accessed July 18, 2016, http://vig.cdn.sos.ca.gov/2012/general/pdf/35-title-summ-analysis.pdf. ↩

- For more information concerning the history of the suit and the current state of play, see California Against Slavery website, accessed July 18, 2016 http://www.casre.org/prop-35/lawsuit. ↩

- For more analyses, including critique of three theatrical representations, see Janelle Reinelt, “Is a Trafficked Woman a Citizen? Survival and Citizenship in Performance,” in Gendered Citizenship: Manifestations and Performance, eds. Bishnupriya Dutt, Janelle Reinelt, and Shrinkhla Sahai (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming 2017). ↩