Come what may the house enables us to say: I will be an inhabitant of the world, in spite of the world.1

This essay presents a piece of performance research that brought together a theatre-maker/performer and a theatre researcher to explore the relationships between theatre and poverty. Our collaboration was just one part of a broader research project, led by Jenny Hughes, that examined contemporary theatre initiatives in sites of poverty and economic insecurity, and that also undertook a historical study of theatre’s engagements with the poor. 2 The use of performance practice as a research method, represented by our collaboration, is common in theatre and performance studies. During our research, this involved the use of techniques from the field of devised performance to engage imaginatively with fragments of information drawn from historical archives, aspects of autobiographical experience, and contemporary accounts of welfare. Practice-based research generates knowledge from working in creative and embodied ways with real and imagined objects, experiences and subjects placed in relationship and dialogue with each other. It can lead to written outputs, as in the reflection that follows here, as well as knowledge and understanding wholly produced and disseminated as performance—in the form of a piece of theatre, or as rough improvisations in the rehearsal room. Our practice-based research took place over two years and led to a solo performance called The House, performed by Carran Waterfield to audiences at four different sites between November 2015 and January 2016.

Carran is an independent theatre-maker and trained teacher who—as she does with The House—creates performances inspired by her family history. Alongside this autobiographical work, Carran has led a range of experimental and educational theatre projects, both independently and as part of the award-winning performance company, Triangle Theater. Working from a Poor Theatre tradition that privileges the performer’s voice and body as a primary medium (dispensing with extraneous theatrical or technological input),3 Carran’s performances create intimate encounters between performer and audience, an approach that combined well with our research imperative here, especially when complemented by the use of solo performance, with its demand that the performer expose herself to vulnerability and risk.

Jenny Hughes is a University researcher and teacher with a history of working in applied and social theatre, and at the time of this collaboration was leading a research initiative exploring theatre and poverty. The selection of performance as a research tool arose from a desire to understand the relationship between the performing body, poverty, and economic inequality, as part of a broader investigation of the political economies of theatre and performance practice. Performance was employed to examine both the experience of poverty and the visual and embodied regimes in which the poor have to appear in order to access social support. These visual and embodied regimes, often stigmatizing and limiting, are reproduced across the contexts of social welfare, including inside social theatre practice.

Built around ten photographs depicting an imagined and theatricalized “pauper concert,” a concert performed by and in aid of the poor, this essay provides an overview of the research process and its outcome. The pauper concert, staged in a Victorian workhouse that becomes a contemporary employment agency, was the central theatrical motif of The House. “Pauper,” a word prevalent in the Victorian period, refers to those in need of public support—government aid or charity—because they do not or cannot earn a living through their labor. The photographs provide an insight into Carran’s autobiographical story, an important source for the research, with her family ancestry (as we discovered during the process) featuring engagements with systems of welfare dating back to the UK’s New Poor Law of 1834. Carran also drew on her experiences of growing up on a social housing estate in Coventry in the 1970s and her working life as a freelance theatre-maker in the decades that followed. It is worth noting at the outset that our shared experiences of growing up in family contexts characterized by economic hardship—of not having enough to go around—was a subject of repeated conversation between the two authors, and provided an important frame through which we reflected on research materials arising from interviews with welfare professionals and activists, visits to archives and workhouses, and work-in-progress viewings. Mirroring the importance of such conversations in our collaboration, the essay is presented as two voices engaged in dialogue, other than in this introduction and the conclusion, where our voices are combined. We hope that this approach shows how our distinct research modalities informed the investigation.

The research traversed a connected array of times and spaces, different “houses” of welfare, and mapped these onto clues left in memories and archives relating to the female lineage in Carran’s family. In his exploration of the resonances of the word “house” for theatre, Marvin Carlson draws on a biblical citation to support his observation that “the theatre—though home to few—has for centuries been a house for the multitudes…the theatre seeks to come as close as any human institution to the term in which Job describes Heaven itself: ‘the house of meeting for all living.’”4 Carlson’s evocation of the house of theatre, considered in the light of Gaston Bachelard’s suggestion that images of the house express dreams of shelter, stability, and intimacy for human life, is extraordinarily resonant for our reflection.5 The citation Carlson uses here is from the Book of Job in the Old Testament, which tells the story of Job, a wealthy and devout citizen who, by order of god, is stripped of everything of value and cast into the wilderness, exposed to disease and hunger, living with and humiliated by the most excluded orders of society.6 Through his ordeal, Job learns of the presence of god in places of suffering, cruelty and death. The phrase “house of meeting for all living,” from Job’s monologue at the heart of the story, is a desperate exclamation of faith in the face of abject dispossession. This dream of a house as a place of exposure and shelter for all, and Carlson’s suggestion that theatre offers such a dream, evokes our critical exploration of the capacity of theatre to create points of encounter with the diverse shapes and forms of life that constitute the disavowed underpinnings of the economic order. The dreams of the house that follow move from the house as place of work and mobilizer of economic growth to the house as shelter for vulnerable life; from the house of theatre as a site of disciplined performance to the house of theatre as refuge for assorted forms of life. By placing the body of a female performer at the center of a pauper concert inside such houses—what kind of “meeting for all living” is materialized? What points of tension between the body and economies of care become identifiable? What relationships between theatre and the economic domain emerge, and how do these mediate between forms of social life and social death?

In our search for a relationship between theatre, performance, and poverty that might contribute to understanding theatre’s role in leveraging social and economic justice, we encountered troubling but also hopeful outcomes. We found that performance is problematically implicated in disciplinary measures that continue to make precarious the lives of those people unable to “perform” in accordance with the exclusionary discourses of good citizenship embedded in liberal and neoliberal economic regimes 7. Here, performance plays a role in maintaining the appearances of justice. However, theatre can also trigger affects that are in excess of its appearances, and provide opportunities for affective encounters with a diffusely shaped social body that is fluid, multitudinous and made up of radically equal parts. Here, performance contaminates, traverses categories and limits, personalizes and inspires—opening up convivial, intimate, and playful spaces for encounter. Perhaps performance does not leverage justice in a direct way, but it can create affective spectacles that determinedly position the spectator inside rather than outside a network of relations with the economically excluded other.

1. The “Home Kids,” 1944

Carran: This image shows a group of girls living in Eastward Ho, Stowmarket children’s home in Suffolk in 1944. The children are having their photograph taken and are in various states of readiness for photographic capture. Some are stood on the ground, some on a tree trunk. Someone is standing to attention, someone else is sucking her thumb, others are running round. The children are all wearing uniformed pinafores and holding gifts. Three soldiers stand behind the girls. One of these might have handed out the gifts. My mum is the fifth from the left standing on a tree trunk and so higher up, to the side of the soldiers. She’s the one with black curly hair.

Her mum—my grandmother—had admitted herself into what was referred to literally and in the local imagination as the workhouse. It was in fact a former workhouse turned into a hospital in the 1930s. My grandmother gave birth to my mum there around nine years before this photo was taken. Mum spent her formative years in a variety of children’s homes and my grandmother—who we called “Nana-in-hospital”—spent most of her life in institutional care, suffering bouts of mental distress before and after the birth of my mum.

The children in the home, known locally as “home kids,” would put on regular concerts for the soldiers, who brought them chocolate. Mum said that the chocolate was kept in a cupboard and not given to the children until it had gone off. Tommy, the Assistant Matron, ran a regime of cruelty and she was the one who trained the children for the concerts, organizing each concert in military style and making the girls sing with nails in their mouths during one party piece. The soldiers were American, from a military base nearby, and they were always visiting. Each soldier “adopted” a girl and on this occasion mum’s soldier had not turned up so she was cross, she says. You will see she is frowning. It was sports afternoon. I asked mum if the children did a concert for the soldiers that day. She said “we were always doing bloody concerts.” Mum said that the matron used to be really nice to them in front of the soldiers but was horrible when no one was there.

2. Dearnley Workhouse (2015 [1877])

Carran: During the research, I visited Dearnley Workhouse (later Birch Hill Hospital) in Rochdale, a small town in Lancashire (UK), as well as other workhouse sites. I used the straight lines you can see in the architecture of the workhouse—corridors, rows of windows, working from shifts in perspective and scale created by the height and sightlines of these structures. The workhouses are so massive in relation to the human form, they make you small, and it must have been terrifying to look up at them, especially for a child. I worked with the terror of being a little person in this huge place, with its corridors and keys. My movements became institutionalized. To find points of physical and emotional connection to the building, I went to the “workhouse” every day to do my job and I found that both inside and outside the rehearsal room I was walking down corridors or going through a particular door in the same way because that was what my work demanded. Even the porters in the university, the location of the rehearsal room, formed part of my imaginary workhouse world as I requested rooms to be unlocked. I carried heavy props from room to room, becoming my own porter. The world of the workhouse fused with the university institution, and both buildings became collaborators in the research. When I carried all my gear I allowed myself to feel that the actual porters were not pulling their weight. It began to help my process that I was alone and “helpless” and it was not a big leap of the imagination to find a role for Jenny as “my visitor” in that world.

We met people who remembered Dearnley when it was still close to a workhouse in operation and had experienced its transformations through the twentieth century, providing human voices connecting the rich fabric of this transforming building. These voices provided a layer of oral history that combined with voices from my own family history.

Jenny: Dearnley Workhouse is a larger version of the workhouse Carran’s mother was born into, but connected to the same history of welfare. The building, originally opened in 1877 to accommodate 900 paupers and described as a “credit and an ornament” to the town, is a fine example of the Victorian workhouse.8 Architecturally spectacular, the Victorian workhouse represented the first centralized system of welfare in England, and it aimed to encourage habits of work in the able-bodied poor whilst improving standards of care for the frail, abandoned, orphaned, and disabled.

The New Poor Law of 1834, which triggered the Victorian program of workhouse building, supported the historical emergence of a competitive labor market required by new modes of industrial work. Here, the poor were expected to act as self-sufficient economic agents, with public aid a last resort.9 As Mary Poovey notes, the New Poor Law introduced “disciplinary individualism as the normative model of agency” and demanded “a peculiar form of self-government from the poor.”10 The New Poor Law also introduced the workhouse test, whereby entrance to the workhouse became the only form of social support on offer, with conditions in the workhouse “less eligible” than the houses of the self-sufficient, laboring poor. Workhouses prevented “moral contagion” by separating paupers into classes according to age, gender, and fitness to work, with a regime of time and place crafted to encourage habits of work and good character through the performance of closely monitored and monotonous forms of labor. The Victorian workhouse is a legislative and material architecture of importance in the history of welfare, including the histories of social theatre. In the decades following its opening in 1877, for example, Dearnley Workhouse became a site for fledgling kinds of social theatre practice that often mapped onto new discourses of work, subjectivity, and identity.11

Part of a rash of interventions into the lives of the poor in the nineteenth century, the New Poor Law helped to conceive the idea of the social arena as a distinct entity, separate from the economic and political domain, what Poovey describes as a “social body.” The “social body” is founded on a separation of the poor, who are included as an isolated part, held in a state of specular and conditional relation to the whole: “The phrase social body therefore promised full membership in a whole (and held out the image of that whole) to a part identified as needing both discipline and care.”12 For Poovey, this social body was a domain in which appearance and the visual became epistemologically dominant, with statistical and scientific methods of observation and accounting legitimizing “ocular penetration” into the lives of the poor.13 This led to the marginalization of the body and its stories as an authoritative basis for knowledge, and its replacement with numerical measures that enabled “every phenomenon to be compared, differentiated, and measured by the same yardstick.”14 The impersonal administrative machinery of the New Poor Law was a particularly stark example of such measures. However, Poovey also argues that the representation of gender often produces a “fault” in the social body “that exposes the contradictions among rationalities and domains.”15 This can be seen in the ways that poor women, particularly single women with children, seen by Poor Law legislators as partly responsible for the newly visible mass of poor reliant on the public purse, became “malleable icons” in the citizenship contests of this period. On the one hand, single mothers were fraudulent, immoral, and in need of rectifying interventions and on the other, they were seen as innocent and defenseless victims of new economies of austerity.16

Our research, which imagined and dramatized the performances of poor women engaging with welfare, traced such points of tension in the social body, revealing their political and economic underpinnings, and their stakes for social life. The resonances of the word “house” are interesting here, as they help identify a strange juncture of fault-lines associated with discourses of female productivity. This juncture is characterized by interweaving discourses of over-productivity (women, as reproductive agents, create a surplus of life), scarcity (women, in their under-productivity or over-productivity—take your pick—are a drain on the economy), and absence (women provide the invisible labor that mobilizes the prosperity of an economy). Interestingly, the etymological root of the word “economy,” oikos, refers to “household management,” an economic system famously explored by Aristotle in The Politics, and in a way that reveals the tensions in the social domain created by the female body especially vividly. For Aristotle, the household represents an ideal economy, as it is a system that produces necessary and useful objects rather than accumulates through speculation. Aristotle’s account of this ideal economy, however, is founded on an extended justification of slave labor and there is also a fleeting mention of its reliance on the subservience of women.17 The Aristotelian dream of the house, then, relies on a disavowal of the work of the body and on cancelling the possibility of prosperous life for a mass of bodies. The workhouse dream, with its sparse rooms and disciplinary lines, supports the survival of a reserve army of labor, but exposes those bodies to humiliation, subjection, and work, eliminating spaces for conviviality and intimacy (at least in official discourses of the Poor Law). In the workhouse—and in contemporary houses of welfare—the dream of shelter is inflected by a demand to perform worth according to narrow measures of economic value. As we will see, this dream regularizes forms of social death, but also materializes performances in excess of itself, in which bodies seek more reciprocal relations with space and inchoate life leaks at borders.

3. Nana-in-hospital, singing (1971)

Carran: This is my Nana-in-hospital singing in 1971—notice her shiny scarf, her pearl necklace, and the flowers on her hat. This photograph was taken at Christmas in her sheltered accommodation, Beech House, where she moved from the hospital. The popular light entertainer Roy Hudd used to attend some of the events organized by Beech House.18 Nana loved singing and during the research, I became attracted to the idea that at the end of the day if you have lost everything you have not lost your imagination or your singing voice.

My mum encouraged us to attend a Non-Conformist Wesleyan Chapel with a strong tradition of singing and amateur dramatics. We learnt anthems and songs with parts. The posh people played in the small orchestra and the children, many of us from the social housing estate, sang in the choir for the Sunday School Anniversary, an annual celebration when everyone got new clothes. The chapel was a place for social mixing, an equalizer. Stricter people in the congregation had problems with “radical” forms of worship like dancing and acting because they drew attention to the body and so displayed the ego. However, singing was always embraced. This meeting of the concert turn and chapel worship also happens in The House. When I look at this photograph what I notice is the sparkle of Nana’s scarf and wonder whether sparkle and singing marked freedom or escape for her.

We move now to reflect on the performance itself, starting with an introduction to four personas who took shape over the course of the work in the rehearsal room. The audience meet these three personas early in the performance, and each, in her own way, sets the stage for the pauper concert that follows.

Hello. Welcome. Well, I think we can say that the house is well and truly open. It’s a good turn out. I’m very pleased that you’ve all turned out so well.

4. The Pauper Portress

Carran: The Pauper Portress, in a strict, matter of fact way, greets the audience and sets the space for the pauper concert. She fetches and carries. She is in the system and of the system. A pauper who has become part of the furniture—literally, she carries it—the Pauper Portress has worked her way up and now works for “them,” the authorities on the other side, because “if you can’t beat the system, just join the system.” Presenting the best face of the institution, she is disciplined, workful, a demonstration of the regime’s success. The audience witness her regular and routine work on behalf of the institution. She’s the rule-reader, playing everything by the book, but there is also an occasional hint of defiance—a mock bow or grimace that she never allows the powers-that-be to see. There is a terror in her and of her, and a sense that she could be violent if she needed to be. At the opening of the performance she is holding all the cards, and threatens to subject the audience to sharing the burden of her work.

In the performance, the Pauper Portress organizes the audience into three groups: the charitable rich, the deserving poor, and the undeserving poor. She initiates two onstage traverse audience groups—the deserving and undeserving poor—into the workhouse regime. She instructs them to stand and fires questions concerning their names, birthplaces and date of last attendance. There was no requirement for the audience to say anything: they simply stood whilst subjected to the initiation, watched by the offstage audience of the charitable rich. The aim here was to imagine and conjure the feelings of a pauper entering the system for the first time.

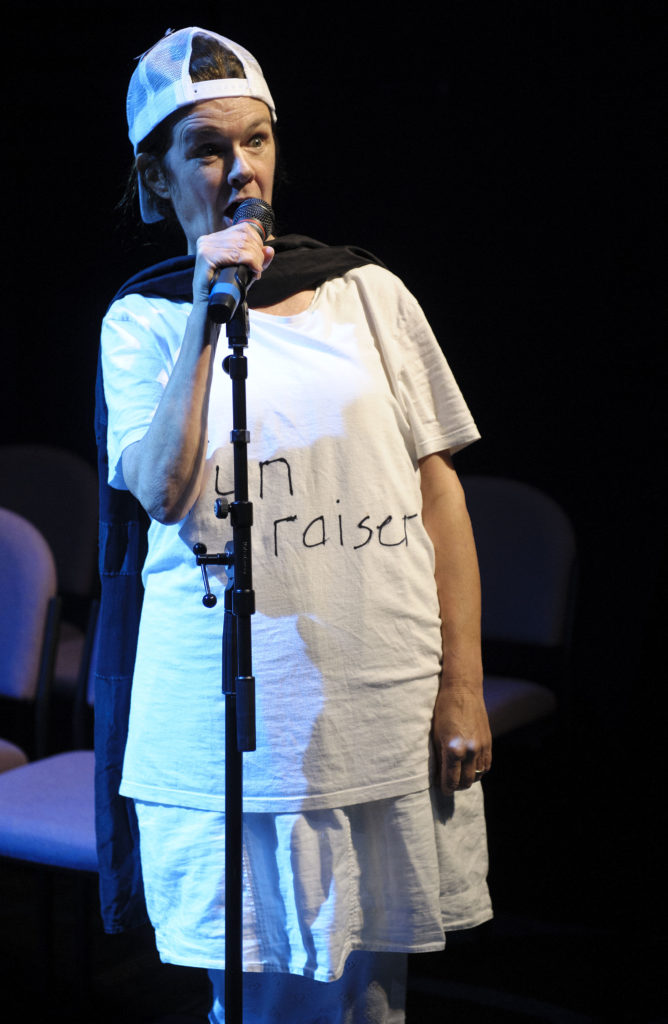

5. The Funraiser

Carran: The Funraiser allowed me to retain the connection with the audience, by turning to address the charitable rich, framed as official visitors and potential benefactors. The Funraiser/Fundraiser is a charity entrepreneur. She welcomes the guests and asks them to contribute to the fun/fund-raising effort. She is deeply patronizing. Keen to show that the money is being spent well she describes the importance of the institution’s three-step improvement program that moves from levels one to three of “the work,” which some of the paupers demonstrate in the concert. Hailing from the great and the good, she is the enterprising patron wheeled out at important events. She is titillated by encounters with those on the other side of society. She does not have to work for a living and owns plenty of posh dresses but wears a cheap tee shirt and cap, on sale during the pauper concert as part of the fund-raising effort, to show that she really cares about the poor.

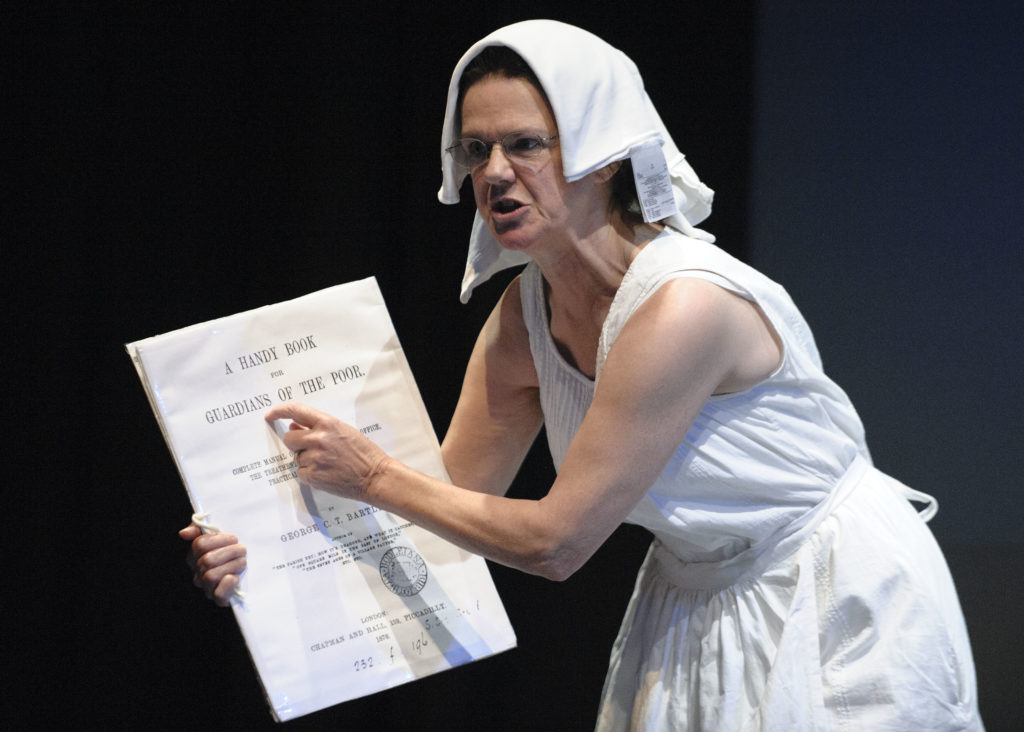

6. The Matron

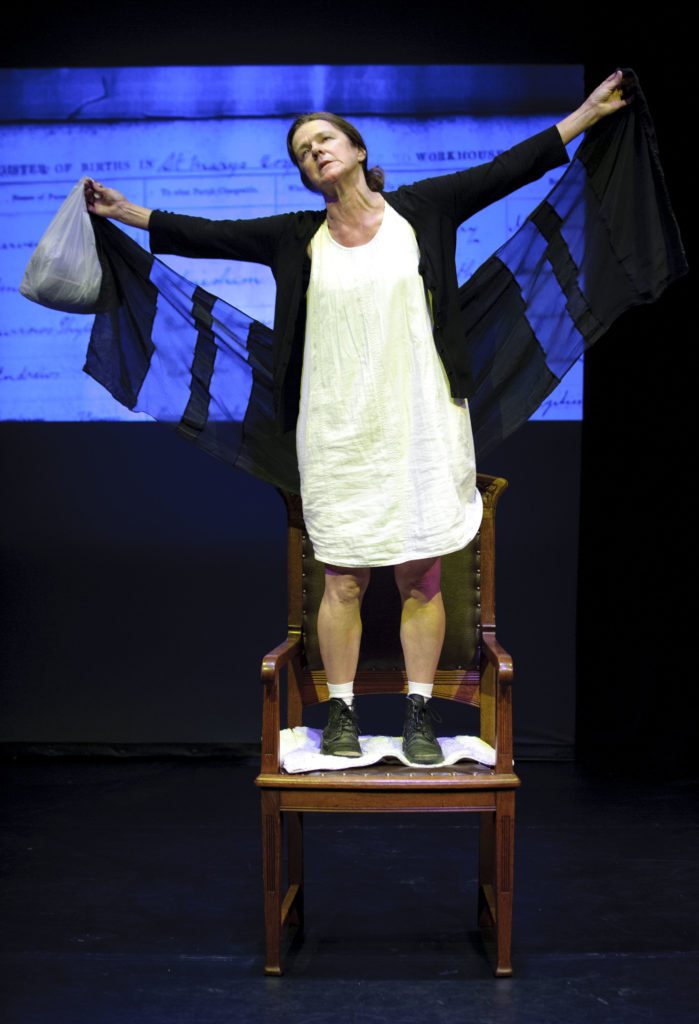

Carran: The Matron of the workhouse recently lost her husband and is about to be redeployed. She wants to better herself and is studying Poor Law administration in the hope of becoming, like the Funraiser/Fundraiser, one of the Guardians of the poor. She has worked at the coalface of the institution but she knows that is not enough—she is not from the elite and so would not look right around the Guardian’s table. She both fears and pretends to embrace her potential scrap-heap demise by being reticent to take the platform herself, yet at the same time ensures that the paupers put on a good show. Almost despite herself, Matron sings a Christian song for the concert—“As the Deer Pants”—a modern Christian hymn, and this moment begins the process of transition from the Victorian era to the present-day. However, the Christian song reveals to her the problem that she has, in that she toes the line about a conventional marriage contract, of being subservient to her husband, and finds she cannot exist on her own in a man’s world. She knows that the next pay check is the last one. In response, the Matron stands on the master’s table, and, by inserting her own words into the hymn, creates a picture of a world in which—as Jenny says—all are equal and queer kinds of caring relationships abound. Jenny describes this as a moment of utopic abandonment during which the world of order falls apart—I agree, but could not have said it in the same way.

7. The Data Protector/Accountant

[Carran?:] The Data Protector/Accountant collects evidence of effectiveness, and ensures that the money in the house is well spent. She appears in the contemporary and historical contexts of welfare in the performance, moving from nineteenth century book-keeper, associated with the ledgers of old workhouses, to twenty-first century hybrid of accountant, health and safety officer, social worker and archivist. She controls the records and keeps them up to date, making cuts where necessary, ensuring that everything adds up and appearances are maintained. She keeps the house in line with quality benchmarks. In many senses, she is a figure of cruelty, the “magpie” to the more emotional figure of the matron, and she is concerned about the “pigeons,” the gutter people—strutting about the streets, “on the make, trying to get something for nothing.” Data Protector/Accountant is a new kind of Master, heralding the changes in welfare practices to come, a kind of Chancellor of the Exchequer brandishing scissors that threaten to cut “some … maybe … some … maybe,” poking at the inmates/visitors/audience. Both Matron and Data-Protector/Accountant sing the same tune: “there’s just too many of them” observes Matron when explaining the problem of the casuals—freelancers, self-employed, migrant workers. The Data-Protector/Accountant emerges from the workhouse ledger, born out of Matron’s rib, delivering herself onto her office chair with a thump. She shrieks as she motors around the space wielding her manifesto of calculated cuts and punitive sanctions. She wages war on the poor. Her starting assumption is that the paupers get more than they deserve and her role is to ascertain evidence of need and monitor the efficacy of the program of improvement in the house. In the piece the slippage between Data-Protector and Matron is keenly worked, and it forms a point of transition from past to present.

Jenny: Welfare regimes in the global North, the context for this research, mobilize technologies of citizenship that produce a narrow spectrum in which the poor must appear, and performance is a medium by which those technologies of citizenship are enforced and resisted. Demanding that the poor appear as economically productive bodies in suspension or in the making, welfare regimes create conditions on appearance that construct what I have come to call a “performance-poverty bind” capturing both recipients and disseminators of welfare in cycles of performance, which in turn mobilize evermore pernicious forms of economic inequality. On the one hand, there are demands for performances of self-entrepreneurship, self-care, and self-investment—the presentation of self as an autonomous and creative unit, in the process of “moving on” into profitable life. On the other—there are demands for “authentic” exhibitions of self as damaged goods—as unfit for work, as bodies that do not work. At both ends of the spectrum, the poor are constructed as in need of civilizing interventions, interventions that may include arts and theatre projects. Here, a female performer—Carran—inhabits the performance-poverty bind, and imagines and embodies modes of self-presentation that reproduce as much as trick and expose the technologies of citizenship that call the poor into appearance.

Taken together, the four characters introduced above describe the technology of citizenship in the house, which moves from caring to punitive forms of discipline with their inherent demands to perform. The characters set the scene for the pauper concert, the specular platform on which the paupers later appear, each trying—and failing—to demonstrate their successful completion of the program of improvement. In her study of welfare agencies in the US through the 1990s, Barbara Cruikshank explores how welfare programs “work on” our capacity to act on our own behalf, via a “will to empower.” The poor are subject to “empowering” interventions that rectify “deficiencies” in “self-acting” energies, but this appeal to act voluntarily in our own interest is also a coercive demand.19 Each turn in the pauper concert holds these “empowering” interventions, with their infusions of coercion and self-agency, up to view. But here, the Pauper Portress’s exaggerated performance of acquiescence, the Funraiser’s parody of the “will to empower,” and the Matron’s ecstatic hymn, materialize self-acting energies that also create fractures in the smooth performances of good citizenship that, as the performance proceeds, collapse into outright chaos.

What is notable about the social domain in which contemporary welfare programs exist is the replacement of discourses of empowerment with the precarious performances of self demanded by contexts of economic neoliberalism. Wendy Brown shows how, with neoliberal forms of economic governance, the “citizen” becomes “an intensely constructed and governed bit of human capital tasked with improving and leveraging its competitive positioning and enhancing its (monetary and non monetary) portfolio value across all of its endeavors and venues.”20 Here, those engaged in welfare regimes are no longer citizens working for or receiving from the common good, nor are they simply creative or entrepreneurial “self acting” agents. They are also, and predominantly, investment portfolios, focused on developing modes of “self care” and “self appreciation” based on speculations of future value.21 For Brown, this leads to the removal of social protections associated with liberalism in its positive sense, adding up to the end of citizenship as we know it. Here, the citizen, formerly protected by political rights to self-determination and a welfare safety net, is perpetually potentially dispensable and at risk of redundancy or abandonment: “the neoliberal subject is granted no guarantee of life (on the contrary, in markets, some must die for others to live).”22 In the UK, as part of the reform of welfare practices, we have witnessed such rituals of sacrifice enacted to a shocking and utterly disgraceful degree. In 2015, after receiving successive freedom of information requests, the UK government released statistics that showed that nearly ninety people were dying per month after a controversial assessment procedure found them “fit for work,” leading to a reduction or removal of their disability benefits.23

Liberal democracy is a project that expresses ideals in excess of itself according to Wendy Brown,24 ideals that she equates with the histories of political liberalism but which, for me, are positioned at a fault-line rather than point of critical potential associated with liberalism. This fault-line is produced by the intense forms of presence generated by the performances inside the pauper concert. Arguably, this fault-line signals the domain of a “common” self as well as a common system of value, beyond the ideal of the autonomous and economically productive, self-acting, disciplined individual who contributes to the prosperity of a liberal economy. Evoking the discussion of Aristotle’s household economy above, (neo)liberal welfare regimes fail to capture the ways in which those deemed unfit for work, marked as bodies that do not work or do not work hard enough, or bodies whose work is not appreciated and does not “appreciate,” might provide the underpinnings of both liberal and alternative systems of value. For example, as Brown herself points out, in neoliberal economies these elided bodies are often feminine, providing invisible and unwaged forms of social care that comprise the “invisible infrastructure sustaining a world of putatively self-investing human capitals.”25

We move in the final section of this reflection to a consideration of the pauper performers, moments of performance that represent our attempt to include the voices of the poor in the research, voices that are often absent from the historical record or only present in disembodied form, as marks in lists and ledgers.

8. The Pauper Chorus

Carran: The emotional fulcrum of The House, the Pauper Chorus, is made up of a series of voices, personas, gestures, and postures that I encountered when physically exploring the word “poor.” The Pauper Chorus leads to a crescendo where these voices come together to recite the hymn “Jesu lover of my soul,” overlaid with the thematic phrase “public money.” These are the voices in the workhouse walls—the forgotten ones, the ghost chorus, sensed in the etched markings left by inmates—neither performer nor audience know who they are and we never see or hear them as distinct characters. There are three shadow paupers in the chorus, defined by age: the child pauper, the adolescent pauper, and the aged pauper. Here, the license created by a physicalized mode of performing allows me to generate “many out of just one.” As a performer, I see this moment of performance as a state of evocation, or “speaking in tongues” to use a Christian reference point, creating the sound of the mass. Towards the end, Matron slides in again, conducting the choir, bringing it to order, so that it ends beautifully tuned and ringing in the air. When performing the Pauper Chorus, I turn on a spiral, shifting through different images of the poor—baby, child, beggar, pointing the finger—accusing, feeling shame, hitting out, internalizing blame. Physically, I am working with a principle of opposition to deal with contradictions in ideas. A fracture occurs, the tension is stretched in both directions, and various emotional and physical states are configured. This part of the performance can be uncomfortable and anxiety-provoking to witness. I am not following a script here, instead I am in a state of evocation of experiences and encounters, and words and fragments that left their presence during the process of research.

Through the recollections of two former members of staff of Dearnley Workhouse in Rochdale, we encountered three women. They were called Beattie, Phyllis, and Alice—we do not know their surnames, and we never met them in real life. They were Rochdale women who spent their whole lives in institutional care and lived parallel lives to my Nana-in-hospital. From reading further, we discovered that this entrapment in regimes of care over decades of life is a story common to many women in this period. Working as a solo performer, I was looking for a cast to be in the play, and these women became part of the performance. They are not represented as “characters” but they are present and, like the workhouse buildings, became collaborators in the process of making. They are like amoeba, raw material, never distinct, and as I walk down the workhouse corridors in each performance they accompany me. The little I was able to find out about their stories begins to unfold in the pre-performance soundtrack, where the audience hear something about their lives in hospital through the recollections of those responsible for their care. More of these descriptions reappear in the final soundtrack, and here they merge into my nana’s story as the piece concludes. Throughout the performance, the human presences described in these recollections inhabit me, and I hope the performance gives voice and body to those forgotten people.

9. Pauper Three (Job-Seeker)

[Carran?:] The confrontation between Data Protector/Accountant and Pauper Three (Job-Seeker), the penultimate image in this essay, represents a shift from workhouse setting to contemporary employment center. Whilst Pauper Three (Job-Seeker) has her historical roots in the Pauper Chorus, especially the adolescent pauper shadow, she is also a child of the 1970s. When it comes to her turn to demonstrate the three-step program, what Pauper Three (Job-Seeker) thinks she should be doing is dancing riotously to a Neil Young track—a track originally released in 1970, when I was fourteen years old, “Only Love Can Break Your Heart.” Unimpressed, the Data Protector/Accountant makes her go back to “level one” and show that she has successfully completed her first step. Pauper Three (Job-Seeker) tries to argue that she can do her dance and her demonstration, but her appeal fails. She wants to be in the concert but she does not quite understand the audition procedure. She is beside herself—she tries to control her movements through her level one demonstration, but is too full of energy. The cling-filmed overturned desk in the photograph, shortly to become a Perspex barrier in a 1970s-style employment center, is a machine that she tries to control in order to demonstrate her level one competence—weaving the cling-film threads around its legs (an evocation of picking oakum, a form of labor in the workhouse, reinvented here as “shit job”). But she cannot contain herself and the machine spirals out of control. At each attempt her offers to the Data Protector/Accountant are turned down because she does not wholly conform to the rules of the game, and at the end of the sequence she finds herself sanctioned and without money or food. This is a picture of totally frustrated creativity and intelligence, with the only avenue of resistance being self-destruction.

Jenny: The system of accounting for the poor employed in the performance research is very different to the system of accounting represented by the Data Protector/Accountant. At one point in the process, Carran said that the Data Protector/Accountant makes the poor accountable and legible by directing them to “come up here, let’s have a look at you, don’t cross the barrier, don’t come too close, stand there, wait there, now you can come in, it will be good for you.” This form of processing avoids contamination by the other whereas, and in her own words, Carran “allows the contamination.” If for Cruikshank “in the strategic field of welfare everyone is accountable but there are no bodies,”26 Carran’s performance amounted to placing the body, and most importantly, a sense of interrelation and interdependence between bodies, into a “bodyless” system of accounting.

The ways in which the lives of the poor are accounted for in the historical record make a pure form of documentary performance inappropriate, just as the photograph could not provide a secure account of the experience of the girls in the children’s home. Instead, The House drew on spectral presences in memories and archives, and left over from actual encounters. As such, the performance is akin to modes of exemplification, vivification, and intense kinds of visibilization that for Miranda Joseph, extending Poovey’s discussion of the abstract representational practices that created the nineteenth century social body, might provide a foundation for a critical practice of accounting. Whilst Poovey reads abstraction as tending towards totalization, Joseph draws attention to a dialectic between particularity and abstraction that directs attention toward “the lived immanence of what is absent, invisible, abstract, and potent” in every form of measure and value.27 By staging a pauper concert to account for the life of its pauper performers, and by deliberately identifying and exaggerating fractures in those performances, The House attends to the credit-worthiness of all its subjects, young and old, frail and robust, excessive and unproductive. Performance does not leverage justice here, perhaps, but it ensures that systems of accounting for and assigning value to life do not settle into narrow identifications on the one hand, or totalizing, flattening and exclusive generalizations on the other.

In part, the issue here relates to the need to map performance’s relationships to power in subtle ways, especially in the domains of social welfare where, as Cruikshank insists, the coercive and voluntary technologies of citizenship mean that “acquiescence and rebellion are not antithetical but can take place in the same breath.”28 The House returns the body to the fold and—in the eruptions of suppressed energy that bring about collapses and breaks—it materializes refusal. But this refusal is terrifying, as we learn from Pauper Three/Job-Seeker. As much as she is frustrated, she desperately wants to prove herself worthy of being included in the concert, of being part of the social domain and guaranteed a life that matters. The dream of the house at this point in the concert is one of cruelty, with the body remaining on a perpetual threshold between inclusion and exclusion. Pauper Three (Job-Seeker) is determined to perform her worth inside the program but always exceeds its constraints and so is told to go away, work more, invest more, try again, try harder. Pauper Three (Job-Seeker) is productive and creative, but cannot fit to the narrow regimes of productivity on offer—she is left outside, furious, face pressed into the cling-film, exhausted by the effort of self-control, spitting and suffocating as she makes her demand for a benefit payment through the impenetrable barrier.

The willful figure, as Sara Ahmed suggests, is often female and her errant energy appears in literature as deviant, wayward, and misbehaving body parts.29 The willful body parts in this scene—the stamps of Pauper Three (Job-Seeker)’s dancing for example, the wild swinging of her hair, her raucous shouting of her song, repeatedly evokes the fault-line between the voluntary and coercive in technologies of welfare that capture the poor female citizen. Here, the body who does not work for a living—spitting, breathing, sweating, and stamping—dances a line between accommodating the demand to perform work and self-destruction. The riotous moves of Pauper Three (Job-Seeker), failing to successfully demonstrate her level one because she wants to dance, show that the project of work on the self always fails, because there is always more work to do. It is, paradoxically, perhaps at this point of despair that the house of theatre provides its most potent dream of shelter. Bachelard notes that dreams of being inside in the face of the outside, or outside looking in, have “the sharpness of yes and no.”30 But he also suggests that there is circularity here, as “outside” can only be understood in relation to “inside” and that a “threshold god” creates porousness in every door.31 Such a threshold god exists here in the form of the audience, who feel for and with Pauper Three (Job-Seeker). In the same moment that the three-step improvement program attempts to discipline her errant energy, Pauper Three (Job-Seeker)’s energetic returns, through creating moments of visceral and affective opening to the audience, highlight the limits of closure.

10. A Fairytale Conclusion

The pauper concert ends with a performance by the aged pauper, drawing on Carran’s research into the life of her Nana-in-hospital and inspired by the photograph of her singing described above. Here, the aged pauper stands on a chair and sings a popular music hall song about a fairy that nobody loves because she is too old and has lost her glitter.32 She tries to fly into the sky, but this fairytale conclusion does not offer any final liberation. The fairy refuses to sing any more verses, falls from the chair, and returns to the institution. But at this point The House moves into a series of readings of lovingly archived fragments from records of Nana-in-hospital’s life, building a moving picture of a life lived in care. This closure situates the one who “failed” to act in her own interests, who did not make an economic contribution, who could not complete “the steps,” in a regime of appreciation, care, and value that is populated by a desire to find points of common connection and association, and that admits all shapes and forms of life.

In reflecting on this research, we acknowledge performance’s implication in exclusive constructions of economic citizenship but also search for an activist theatre practice—one that might contribute to understanding the value of performance for leveraging justice. What did we learn? From the perspective of social practice—including social theatre practice—our discoveries point to the need to think carefully about the regimes of appearance in which we participate as artists—what forms of accounting are we acting out? There is a need to work inside our “projects” and “programs” in ways that open up possibilities for common relation and that also mobilize alternative forms of identifying and distributing value and resource. As part of this, there is an imperative to nurture a social theatre practice without a plan, without a project, as well as to create programs and projects that provide the protective cover needed whilst we build houses for multitudes (to refer again to Carlson). We need time and space for privileging stories of false starts, failure, and collapse over narratives of recovery, only drawing on narratives of redemption and survival to develop a different kind of practice, a practice that might take years rather than weeks to materialize. Here, instead of chasing bodily and social forms that “work” in the short-term we might gather together willful parts and allow for creative contaminations via ghostly encounters across time and place. To return to Sara Ahmed, such gatherings might create conditions for new kinds of relationship: “Wandering parts can wander toward other parts, creating fantastic new combinations, affinities of matter that matter. Queer parts are parts of many, parts that in wandering away create something new.”33

The House does not work without its audience. It does not work for itself. In that sense it is just like any other piece of theatre—it needs an audience, but an audience of a particular kind. The piece has been carefully framed within a research context and outside of that context it may be misconstrued, dismissed, and even misrepresented. It is not a commercial piece. Perhaps it should be performed for free, supporting protest campaigns, fundraising on behalf of the “small fish” in the “Big Society” or performed in heritage sites, whispering amongst the walls of disused Victorian buildings. Or maybe it should be performed at lunchtime in the House of Commons in the UK Parliament. We do not know but we are pleased that the performance has a life beyond itself. As part of this, we are pleased that the performance and its errant bodies have to some extent escaped imprisonment in an archive at the mercy of the next data protector. The House is a representation of a life’s journey and it is the first declaration of a set of unknown stories, not yet researched, which have much more to tell.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mary Wade and the Waterfield family for generously sharing their experiences. The research was supported by an Arts and Humanities Research Council Early Career Fellowship (grant reference AH/L004054/1).

Notes

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994 {1964}), 46-7. ↩

- Outputs from the “Poor Theatres” research project include a series of academic publications as well as an online resource containing documentation of social theatre projects engaging with issues of poverty and economic inequality nationally and internationally. This resource can be found on a research website, where readers can also view Carran’s “Working Diary” on the practice-based research: http://www.manchester.ac.uk/poortheatres (accessed March 25, 2016). A detailed account of the performance practice as research methodology, together with a script and audience responses to the performance, can be accessed via: Jenny Hughes and Carran Waterfield, “The House: A Curated Portfolio in Five Parts. A Practice-Based Research Project Exploring Theatre, Performance, and Poverty,” Studies in Theatre and Performance 37, no. 1 (2017, forthcoming). ↩

- Jerzy Grotowski, Towards a Poor Theatre (London: Methuen, 1969). ↩

- Marvin Carlson “House,” Contemporary Theatre Review, 23, no.1 (2013), 31. ↩

- Bachelard, Poetics, 3. ↩

- Job. 30 (New American Standard Version). ↩

- As will become clear, our thinking about citizenship has been influenced by Wendy Brown’s account of the challenges posed to liberal discourses and practices of citizenship by neoliberal economic regimes (see discussion below). ↩

- Rochdale Observer, December 22, 1877. Available via the microfiche archive held at the Local Studies Centre in Rochdale (Lancashire, UK). ↩

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001 {1944}), 86-7. ↩

- Mary Poovey, Making a Social Body: British Cultural Formation, 1830–1864 (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 112. ↩

- For an account of theatrical entertainment in Dearnley Workhouse, see Jenny Hughes, “A Pre-History of Applied Theatre: Work, House, Perform,” in Critical Perspectives on Applied Theatre, eds. Jenny Hughes and Helen Nicholson (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 40–60. ↩

- Poovey, Making a Social Body, 8. ↩

- Ibid., 35. ↩

- Ibid., 9. ↩

- Ibid., 16. ↩

- Lisa Forman-Cody, “The Politics of Illegitimacy in an Age of Reform: Women, Reproduction, and Political Economy in England’s New Poor Law of 1834,” Journal of Women’s History 11, no. 4 (2000), 150. ↩

- T.A. Sinclair, trans., Aristotle: The Politics (London: Penguin Books, 1951). See in particular: Books IV–VI. ↩

- Roy Hudd is a stand-up comedian, radio host, and television actor, well known in the UK. ↩

- Barbara Cruikshank, The Will to Empower: Democratic Citizens and Other Subjects (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1999), 38-9. ↩

- Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (New York: Zone Books, 2015), 10. ↩

- Ibid., 33-4. She draws here on Michel Feher, “Self-Appreciation; or, The Aspirations of Human Capital,” Public Culture 21, no. 1 (2009). ↩

- Ibid., 111. ↩

- Patrick Butler, “Thousands Have Died after Being Found Fit for Work,” The Guardian, August 11, 2015, accessed March 15, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/aug/27/thousands-died-after-fit-for-work-assessment-dwp-figures. ↩

- Brown, Undoing the Demos, 206. ↩

- Ibid., 106–07. ↩

- Cruikshank, The Will to Empower, 117. ↩

- Miranda Joseph, Debt to Society: Accounting for Life under Capitalism (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 15. For Joseph’s discussion of Poovey’s abstraction, see xviii-xix. ↩

- Cruikshank, The Will to Empower, 41. ↩

- Sara Ahmed, Willful Subjects (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014). ↩

- Bachelard, Poetics, 211. ↩

- Ibid., 223. ↩

- “Nobody Loves a Fairy When She’s Forty” by Arthur Le Clerq (1934). ↩

- Ahmed, Willful Subjects, 193. ↩