Note: This work includes discussions of childhood sexual abuse, incest, domestic violence, rape, and self-harm. None of these traumatic events in my life are discussed in detail in this piece but rather are represented as memories/flashbacks in the art I have created. If these topics are triggering for you as a reader, this may not be a piece that is right for you to engage with at this time.

Introduction: assembly required

This art was made in bed. As Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha explains, “writing from bed is a time-honored disabled way of being an activist and cultural worker.”1

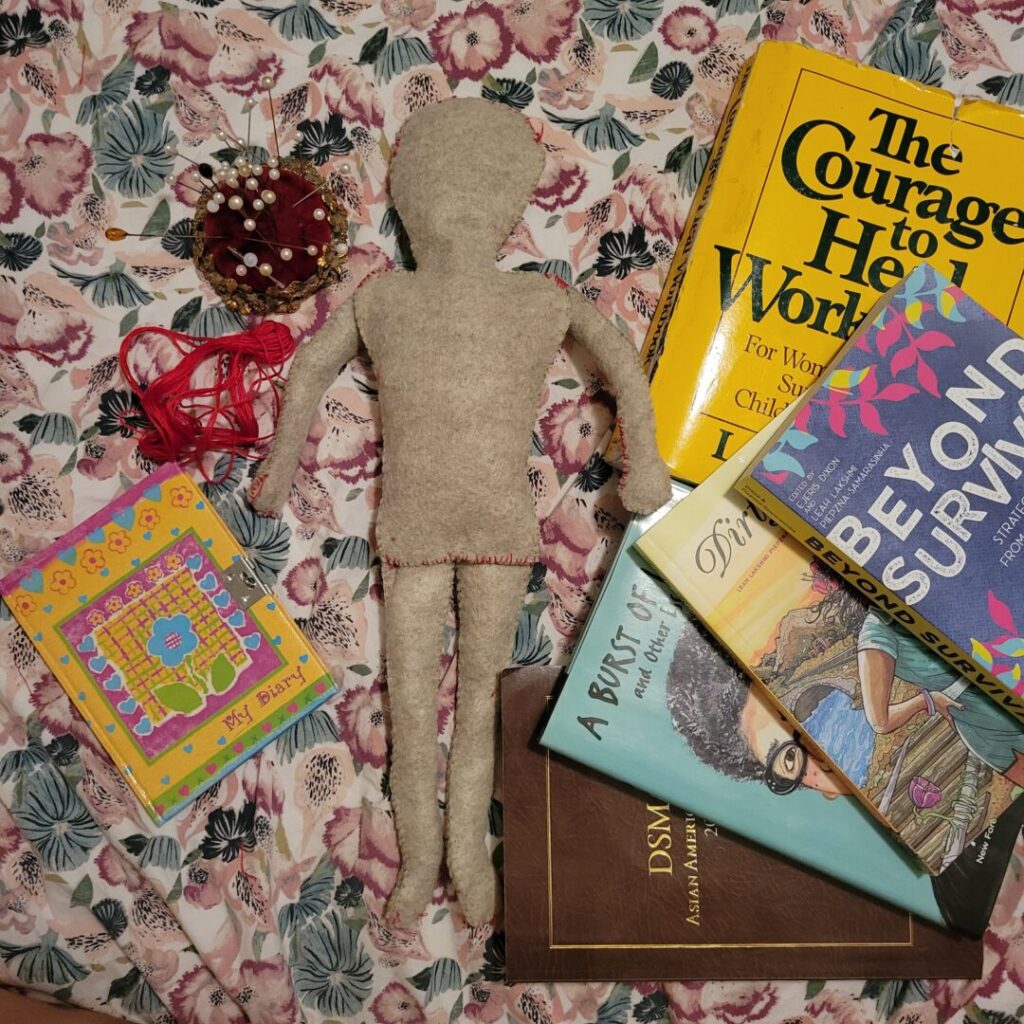

Last summer I slowly read through Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s edited collection, Beyond Survival (2020), in the midst of experiencing PTSD flashbacks, hallucinations, paranoia, a barrage of memories of childhood sexual abuse (CSA), and an overwhelming feeling of isolation during the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic.2

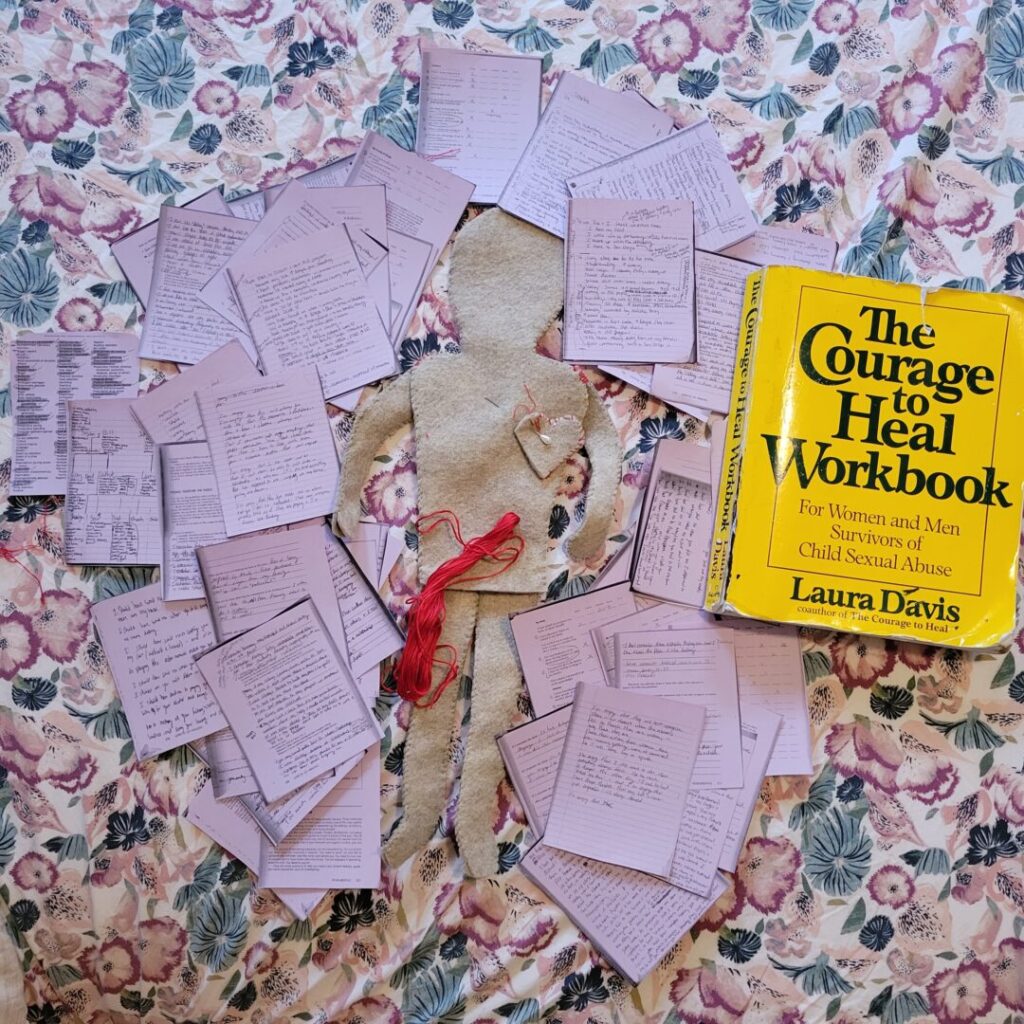

After months of increasing paranoia, visual and auditory hallucinations, intrusive thoughts of self-harm, and severe anxiety, I reached out to a therapist for the first time since 2013. From there I joined a CSA group therapy and we have just now concluded our group after over a year and a half. We worked through the Big Yellow workbook, a.k.a. The Courage to Heal, meeting once every week.3 I will admit I still often felt a pang of hesitancy in this group, but it is also the only space where I have been able to simply speak and show my thoughtfeelings relating to my childhood sexual abuse without shame or discomfort.4

I have found support through transformative justice perspectives, my childhood sexual assault support group, new psychiatric medications (although none of them actually ended up helping me), and the many necessary mad and disability community virtual events. These have helped me grow with my madness, and to build out my care web or pod.5 And importantly, these resources/supports have given me space to practice reaching out for help when I need it6—especially during a global pandemic that physically and emotionally isolated me.7

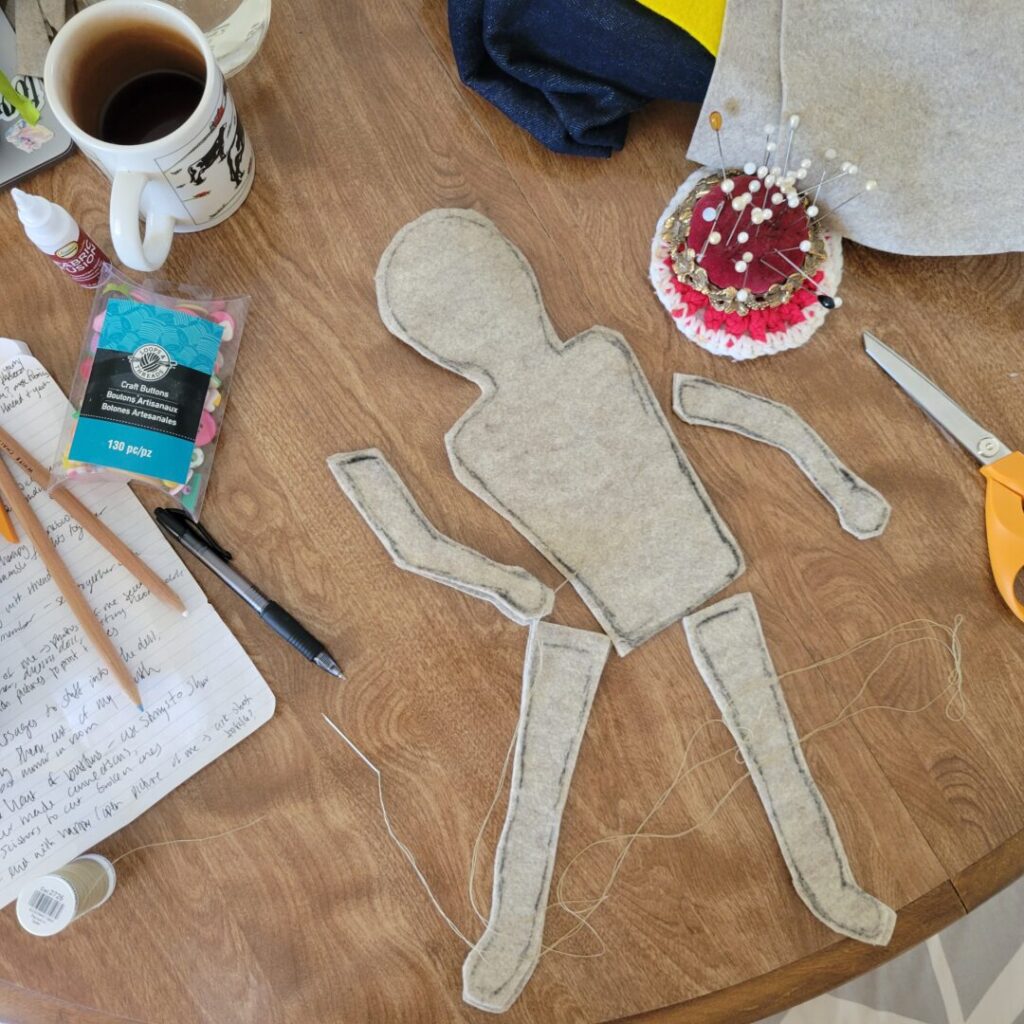

This art has taken years to formulate, and years to process the trauma and abuse I have experienced—yet it feels like now it has all spilled out of me at once, and this is my way of stitching myself back together. This imagery draws from Anzaldúa’s concept of “the Coyolxauhqui Imperative.” She describes Coyolxauhqui as “your symbol for both the process of emotional psychical dismemberment, splitting body/mind/spirit/soul, and the creative work of putting all the pieces together in a new form, a partially unconscious work done in the night by the light of the moon, a labor of re-visioning and re-membering . . . . With the loss of the familiar and the unknown ahead, you struggle to regain your balance, reintegrate yourself (put Coyolxauhqui together) and repair the damage.”8

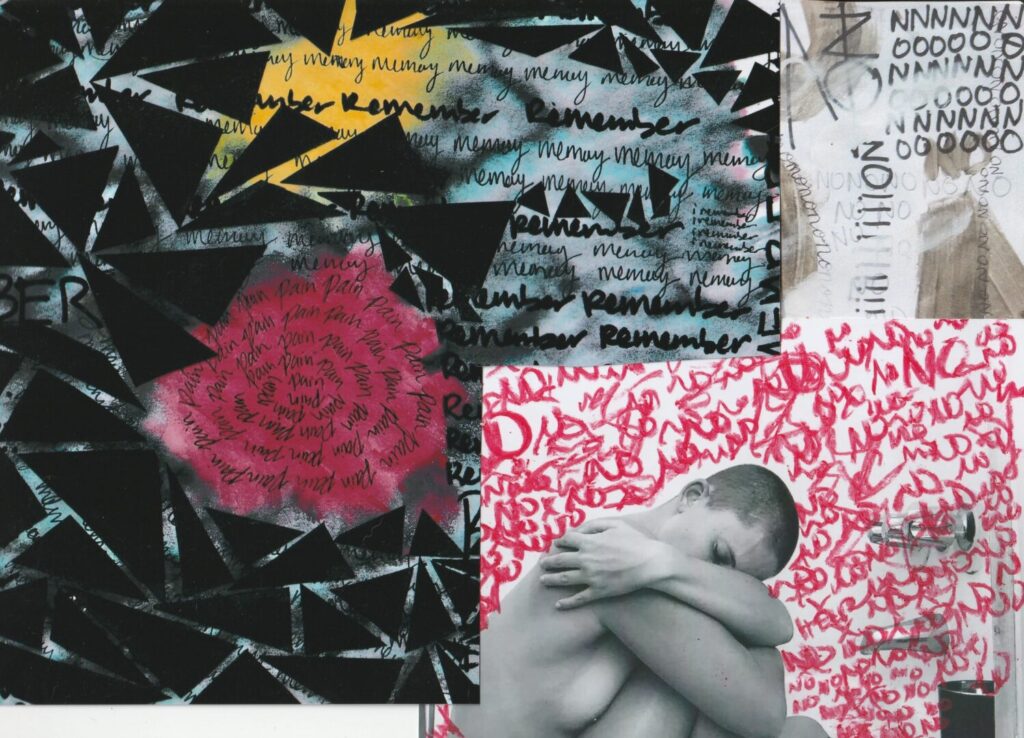

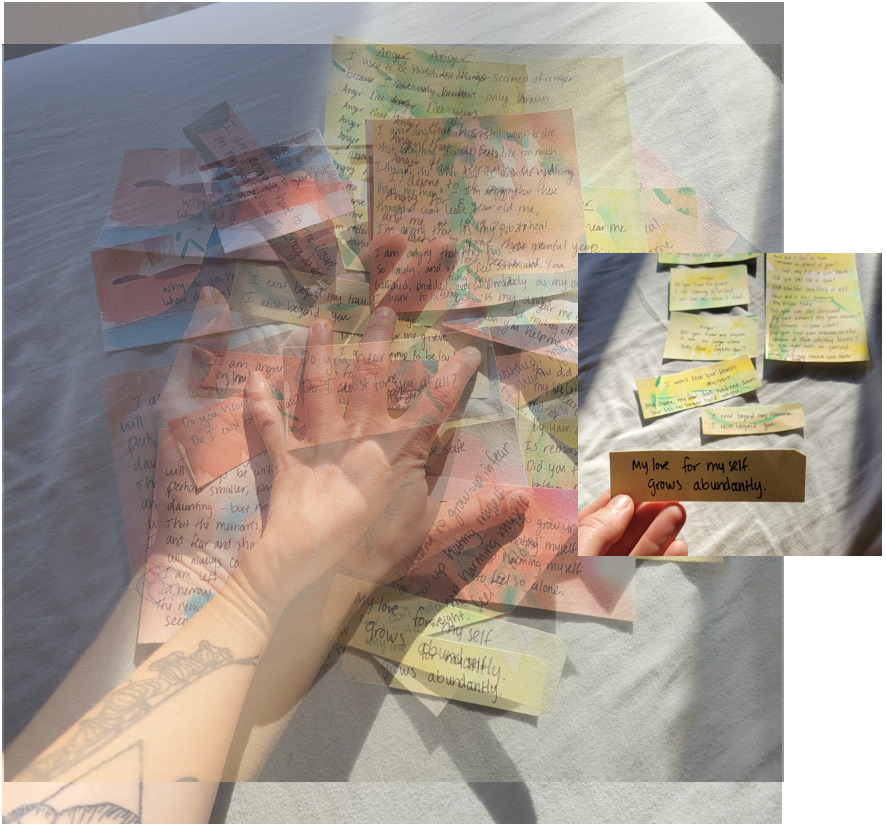

To represent my thoughtfeelings, I have utilized short journal entries, poetry, photos, marginalia9, mixed-media art, collaging and hand-sewing/handcrafting. Through this assemblage of art-making styles I want to accurately represent the overwhelming and overstimulated experiences I had, and continue to have, during this ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This layering and usage of multiple textures, fabrics, and materials represents the muddling of time and the overwhelming experience of “crip time” in a chronically ill and mad bodymind.10

More specifically, I have chosen to bring in photographs of these art pieces, because, as Laura Lee writes in her memoir “A History of Scars,” “as a writer I see trauma can’t be captured in isolation – it can be measured only in images, quantified only in its aftereffects.”11

Moreover, the experience of madness does not allow itself to fit into traditional academic structures.12 This assemblage aims to highlight the dual actions of the destruction of language by physical pain,13 where I am at a constant lack of words, and yet also drowning in the over-abundance of them. A symphony of ways to say I am hurting, please listen.

Yet also, a space where I have found joy in creating art, to find joy in my madness, and to find joy in “slow growth” or “minimums” as self-care.14 A slow piecing back together of myself, the building of my support system, and the joy of finding mad and survivor communities during this pandemic.

This art was created intentionally, with every hand stitch, brush stroke, or the slow precise placement of collaged documents and photos onto my scanner in my bedroom. I reflected on my slow climb out from the shame and overwhelming sadness, anger, and pain from the abuse. I reflected on how I am able to offer care for myself, to connect with past and present me on my own terms.

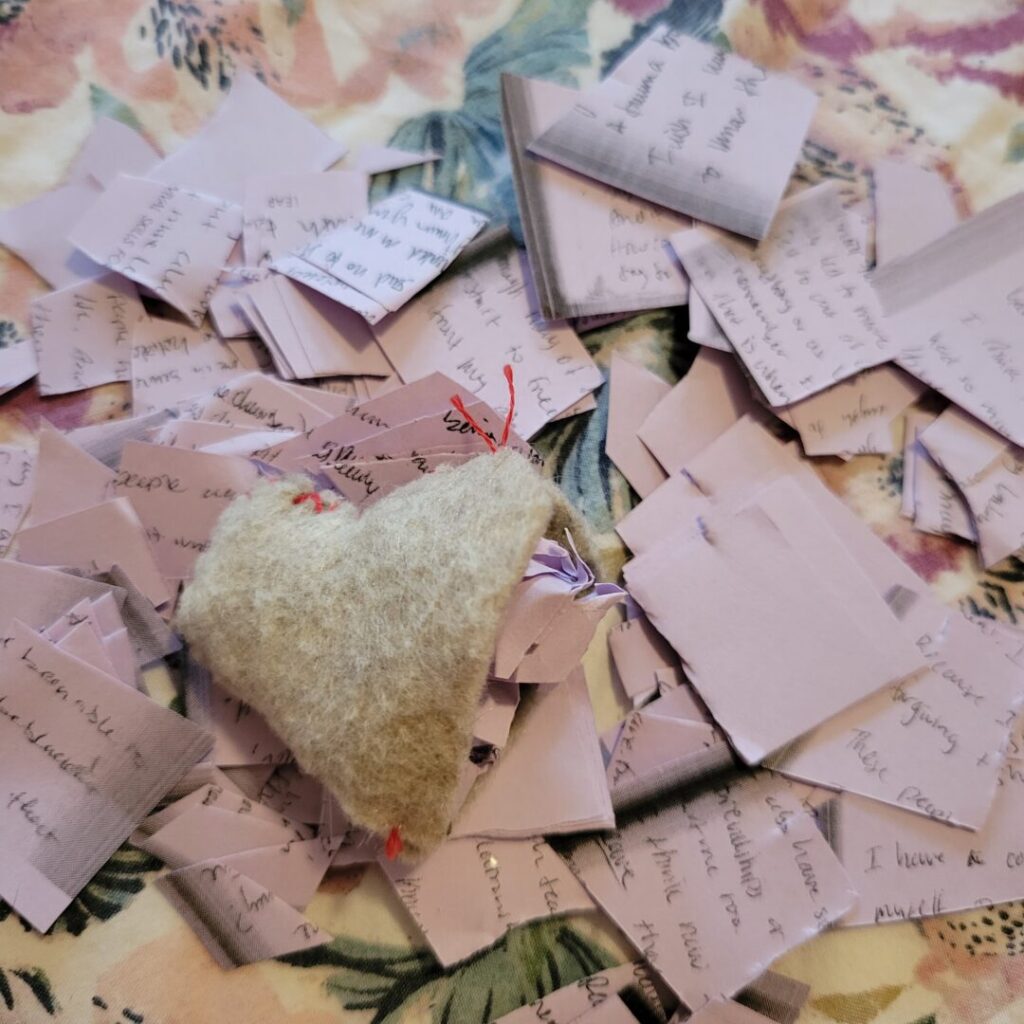

Figure 1d. Trauma is memory, re-memory,15 lack of memory. Trauma studies tells us that while we may forget, our bodies remember. How can we teach ourselves to also remember to heal, to care, to love ourselves. A set of three photographs taken by the author, of them filling a light tan felt doll with photocopied pages from their CSA group workbook, The Courage to Heal Workbook. From left to right: (1) The felt doll is on Sav’s bed surrounded by small purple sheets of paper of photocopied pages of The Courage to Heal.16 The large bright yellow workbook is next to the doll, and there is red string on top of the doll; (2) A close up photo of the felt heart being filled with photocopied writing entries from the workbook. These entries are comprised of Sav sharing their story of their abuse; (3) A photo of the felt doll next to shredded pages of the purple photocopied pages of The Courage to Heal before being used to fill the cavity of the doll.

Paranoia

Your shadow has followed me since I was child.

Then, You were my grandfather. Or perhaps the old man who died in Our childhood home. Perhaps You are all of Them, lurking in the corner of mine and my sister’s room.

Us

Huddled on her bed, the top bunk. Scared.

Trying instead to focus on the local radio station playing from the stereo in Our room.

Us

Watched at night by the rows of porcelain dolls lined up on the top shelf until we begged our mom to move them.

I wonder where they ended up.

Probably in the basement among the towers of boxes and bins filled with dead relatives’ belongings my mom won’t bear to part with.

Haunting Us from beneath the foundation.

Us

Now living together again in Tucson in a different kind of haunted house. One full of family secrets and shame finally spoken. One with two inhabitants trying, willing, themselves to forget the abuse.

Paranoid.

You followed me here. Watching me at night, sidled next to the saguaro outside my window.

Now my sister is upstairs and there is no bed to share. You and Him and Him and…

Now there is too much pain between Us.

We yell, and try to hide in our Quarantine house. Everything is suffocating. There is too much noise and too much silence and too much weight between the two levels of our home. We now have too much in common, and yet nothing at all.

There You are, waiting still. The flash of shadow across the walls while I do the dishes, the crawling bugs on the floor – morphing in size as they move. I double check my room, my closet, my bed. I feel crazy. I hear your nonsense whispers, and flashbacks to Bad memories. It is too much noise inside my head. I am being watched, enveloped.

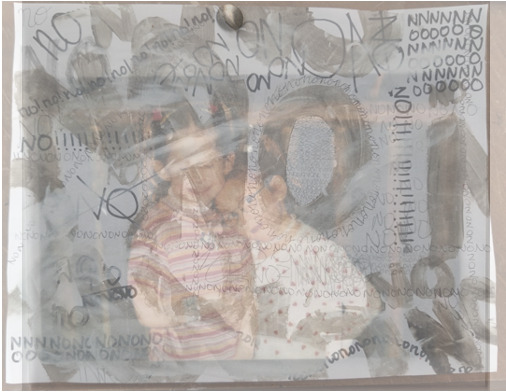

Figure 2b. How does it feel to be enveloped, swallowed whole, by your trauma? To be trapped? Watched? Haunted? From left to right: (1) A self-portrait of Sav taken in April 2020 in the “quarantine house.” Sav is sitting on their bed facing their large window and wearing a gray sweatshirt and rose-colored underwear. Around the photo, Sav has used acrylic and oil-based paints to draw out shadows surrounding them coming in from the window. There are many plastic eyes adhered to the photo and around Sav, with a large red figure made with acrylic paint sitting next to them. (2) A photo taken of the “quarantine house.” Many trees, desert brush, and cacti envelop the house and the sun is setting. Sav has used acrylic and oil-based paints to draw out a large shadow figure enveloping the house, with watching eyes. There is a red figure made with acrylic paint from within the shadow figure. The two photos taken by Sav have been painted over to depict the visuals and sensations felt by Sav. There are several photos from this series overlaid on top of each other to create a blurred and disorienting feeling.

I am transported back to my childhood room, and that closet that He made with the sliding doors that often fell off their hinges. The room is lit by the church parking lot lights next door. I am willing my eyes to say shut, hoping to fall asleep quickly.

Back to that sad apartment with [redacted] and the collapsing walls. With all my things in boxes, just like my mother’s basement.

Except now I am the only dead one inside them.

Except now my mother is repulsed by this site—the day she moved me out, with everyone quickly walking up and down those rotting back stairs—My mother tells me she vomited in the parking lot, sick to her stomach at what has become of my life. Of what [redacted] had done to me.

Back to my Grandparent’s home in the suburbs, hiding in a closet, my mother’s childhood closet to be precise. Watching [redacted] outside the window. He has found me. I never gave him this address and he has found me. The home where that summer I slept in the same room my uncle lived in before he died. Some of his things are still on the dresser. The house with the closets full from my grandmother’s hoarding. This house too is haunted, filled with grief hidden in mountains of things.

Back to the apartment with the ivy, and me, pacing the floors watching the windows waiting for Him to come home. Later, curled into a ball on the bed—please don’t touch me. I’m sorry. Please don’t yell. I had hoped this home would be different.

Back to the apartment in San Diego, sitting in my bathtub, flooded by memories I didn’t know I had forgotten. Rewriting the childhood I had convinced myself I had.

Now, in Our Quarantine Home, with the rats in our air ducts and You outside my bedroom window—sometimes touched by the bright moonlight in the Sonoran Desert, and other times plunged into darkness among the javelinas, coyotes, and the two tarantulas who have burrowed in Our backyard next to the mesquite tree.

I am afraid I will be found again. I am afraid for my sister. I mourn the distance between Us now. I mourn the fact that we weren’t given a childhood without pain. I mourn that I couldn’t protect her.

I am reminded that I often would try to sleep in the hallway between all of Our rooms as a child. Listening to the breaths of the 7 other people in the house alongside the quiet radio chatter. Hoping to keep everyone safe and where they should be.

But they weren’t safe.

And now here I sit.

Watching the walls, waiting for You.

Thoughts on anger.

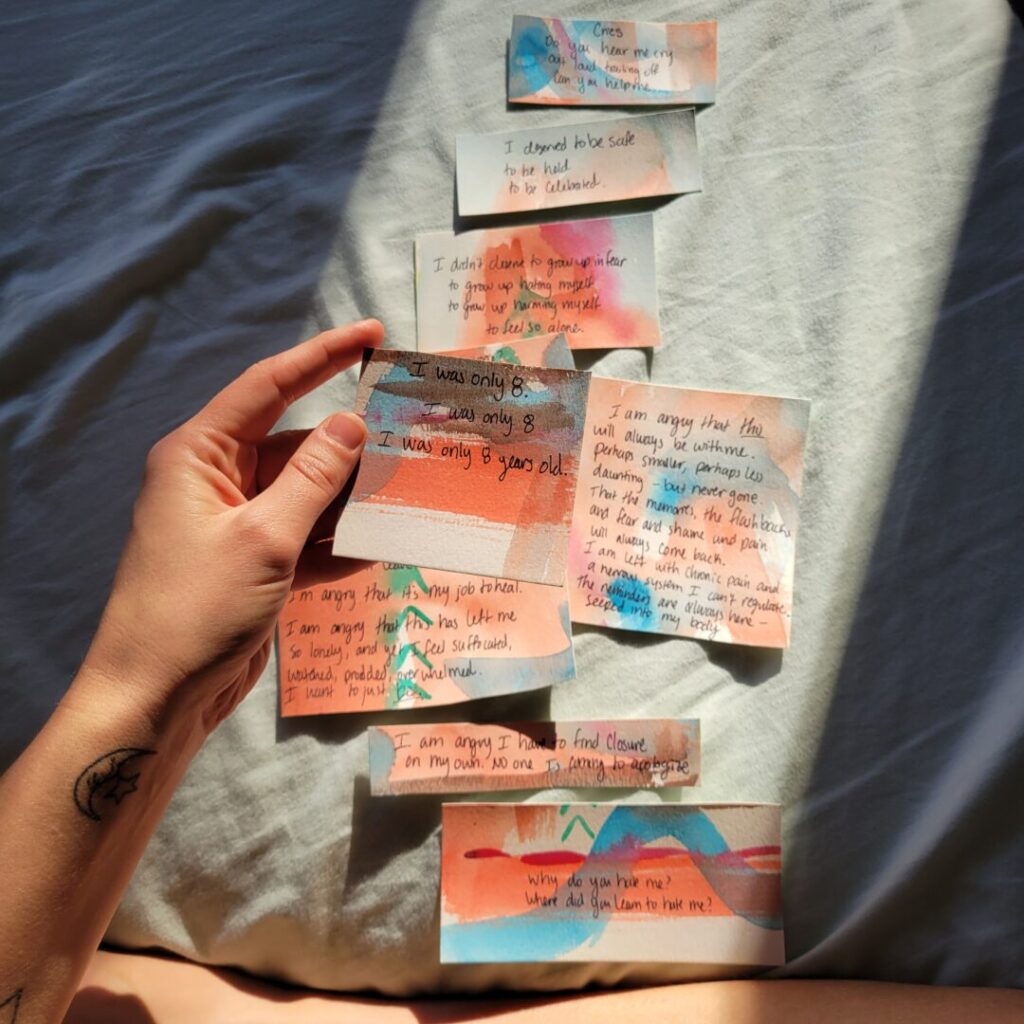

Cries

Do you hear me cry

Out loud trailing off

Can you help me17

I was only 8

I was only 8

I was only 8 years old.

I deserved to be safe

to be held

to be celebrated.

I didn’t deserve to grow up in fear

to grow up hating myself

to grow up harming myself

to feel so alone.

Do you hear me?

Do I exist for You at all?

I am angry.

I am angry that I still want to die

that everything always feels like too much.

I thought the other day “I wish he had killed me then” –

I’m angry that these thoughts won’t leave.

I’m angry that it’s my job to heal.

I am angry that this has left me so lonely, and yet,

I feel suffocated, watched, prodded, overwhelmed.

I want to just be.

I am angry that this will always be with me.

Perhaps smaller, perhaps less daunting – but never gone.

That the memories, the flashbacks, and fear and shame

and pain will always come back.

I am left with chronic pain and a nervous system I can’t regulate.

The reminders are always here – seeped into my body.

I am angry I have to find closure on my own.

No one is coming to apologize.

Why do you hate me?

Where did you learn to hate me?

Anger.

I used to be so scared of anger because I had only known Anger like Yours.

Anger that hurts

Anger that destroys

Anger that seeps into everything.

I deserve to be angry.

Angry for 8 year old me

And me at 18, 19, 20, 21….

I deserve to grieve those painful years.

The time I lost because of You.

I am reclaiming my body as my own

I am taking back my anger.

Anger.

Do you hear me?

Do I exist for you at all?

How did it feel to have someone so afraid of you?

To hold my life in your hands?

Did you feel like a God?

Do you feel anything

at all?

How did it feel dragging

my lifeless body

Did you ever feel disgusted by your actions?

By your desires?

Is remorse in your orbit?

Did you find your answers at the bottom of that whiskey bottle?

Do you look at yourself in fear?

When did you realize you never loved me?

Anger.

Do you hear me grieve

I am learning to be loud

I will take the space I need.

Anger.

Do you hear me mourn

I am no longer alone

Does that frighten you?

I won’t keep your secrets

Anymore.

My shame, my fear, don’t hold me down.

Your lies no longer hold weight.

I exist beyond my trauma

I exist beyond You.

My love for myself grows abundantly.

Before/after

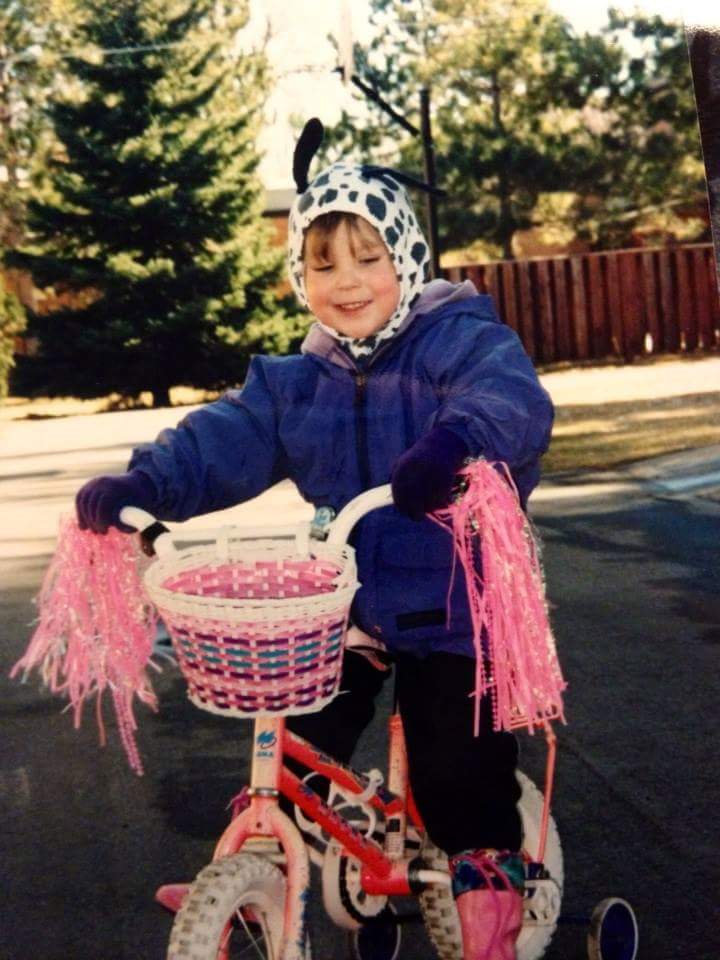

My therapist said that you can often tell in pictures when the abuse started by looking at someone’s eyes.

That something has left, or perhaps, nestled in to stay.

Before.

I remember as a kid going to my dad’s optometry office and having him project our irises onto a small television screen. My siblings and I would all huddle around it imagining a new landscape among the green, blue, and brown textures in our eyes.

My eyes are the exact same gray/green as my father’s . . . and his father’s.

This fact is unsettling.

After.

In middle school my dad started carrying colored contacts at his practice.

Dark greens, browns, vibrant blue, purple.

I wore these with an immense sense of happiness.

Happy.

I keep photos of me before surrounding the ornate full-length mirror in my room.

To connect to the joy of preschooler me on my hot pink bike with training wheels, rolling down the driveway of my childhood home wearing a 101 dalmatian hoodie—complete with actual dog ears. Happy.

I see this now in my adult sparkly hot pink bike, which I ride for miles through the desert. Every month I go to a WTF ride,18 and we ride together down the streets of Tucson—with music coming from the portable speaker someone has brought. I can see so many stars in the sky here. I know preschooler me would have loved this. Happy.

Figures 4b & c. There’s something here about the body remembering how to ride a bike and muscle memory, or inner-child work, or reframing my “after.” Not all afters need to be sad. we can have so many afters that are full of happiness. I can re-write the green of my eyes to be connected to the ever-green bark of the palo verde tree, and start a new familial connection. Top: a photo of Sav when they were in preschool, riding their bike in the driveway of their childhood home. There are many tall pine trees in the background. The bike is bright pink with a woven pink, white, blue, and purple basket, with pink streamers coming from the handles. Sav is wearing a Dalmatian hoodie under their puffy winter coat. They are smiling. Bottom: A photo taken of Sav from 2021 from a community ride in Tuscon, Arizona. Sav is standing with their pink sparkly bike. Behind them, there is an old town fountain and a community mural depicting the Sonoran Desert. Sav is wearing a white tank top, brown dress pants, green cloth mask, fanny pack, and baseball hat.

Mending: a commitment to myself

Naomi Ortiz explained in a workshop I attended this last year that they don’t use the term healing, but rather mending.

Mending.

This is me pulling myself back together19 “after” trauma – if you believe that there is ever truly an “after” or a “post” that exists for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Mending.

This is me, reconnecting to myself without fear.

Mending.

This is me taking the time to care for myself, to listen to my needs.

This is me, still existing. Beautifully. Lovingly. Joyfully.

Figure 5: Rupture provides fertile grounds for new possibilities. A set of three photos of an in-progress cross-stitch piece made by Sav of a large red heart. In the leftmost image, there are two superimposed images of scissors cutting the heart down the middle. In the middle image, the heart has been mended with black thread. In the rightmost image, small yellow flowers have been stitched along the edges of the black thread, and a yellow marigold flower has been sewn next to the heart.

Moments of Joy During a Global Pandemic

Notes

- Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. (AK Press, 2018), 15. ↩

- Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, eds., Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement (AK Press, 2020). ↩

- Laura Davis, The Courage to Heal Workbook: For Women and Men Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse (Harper Perrenial, 1990). ↩

- I draw the use of thoughtfeelings from Laura I. Rendón’s Sentipensante Pedagogy meaning of sensing/thinking and from work in a graduate course on Feminist Pedagogies with Dr. Irene Lara. Laura I. Rendón, Sentipensante (sensing/thinking) Pedagogy: Educating for Wholeness, Social Justice and Liberation (Stylus Publishing, 2009). ↩

- For “care web,” see Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work; for “pod,” see Mia Mingus, “Pods and Pod Mapping Worksheet,” Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, 2016, https://batjc.wordpress.com/resources/pods-and-pod-mapping-worksheet/. ↩

- “I am not ashamed to let my friends know I need their collective spirit—not to make me live forever, but rather to help me move through the life I have. But I refuse to spend the rest of that life mourning what I do not have.” Audre Lorde, “A Burst of Light: Living with Cancer,” A Burst of Light: And Other Essays (Courier Dover Publications, 2017). ↩

- “Who taught you to sort out your pain in silence?

To stop crying so loud, too often, too much.

When crip time is chronic, it means learning to live in a state of listening to your bodymind.

This act of listening isn’t easy.

But does it have to be done alone?

My chronic pain and illnesses have filled me up with aches and loneliness.

But have also taught me how to tend and care for others.

To listen to their pains.

To help make them laugh.

To sit, or lay, in crip time together.

We experience so much of this in the same timespace, but I find myself retreating inward when I become overwhelmed.

To hoard my pain until it becomes a hard rock in my stomach and weights down my limbs.

Until my bruises bloom on the surface of my skin.

My body shouts out my pain for me when I hold my words back.

I’m lonely.

I need care.

I too need someone to listen.”Originally presented at “Making Sense Conference” in 2020, drawing from Ellen Samuels, (2017). “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time,” Disability Studies Quarterly 37, no. 3 (2017): https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5824/4684. ↩

- G. E. Anzaldúa, “Now let us shift . . . the path of conocimiento . . . inner work, public acts,” in Light in the Dark/ Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, ed. G. E. Anzaldúa and A. Keating (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2015), 124–125. ↩

- Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020; Mimi Khúc, ed., “Open in Emergency,” special issue, Asian American Literary Review 10, no. 2 (2019); Alison Kafer, “After crip, Crip Afters,” in “Crip Temporalities,” special issue, South Atlantic Quarterly 120, no. 2 (2021), 415-434. ↩

- Ellen Samuels, (2017). “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time,” Disability Studies Quarterly 37, no. 3 (2017): https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5824/4684; Alison Kafer, Feminist Queer Crip (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013); Margaret Price and Stephanie Kerschbaum. (2016). “Stories of Methodology: Interviewing Sideways, Crooked and Crip,” in “Telling Ourselves Sideways, Crooked, and Crip,” special issue, Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 5, no. 3 (2016): 18-56. ↩

- Laura Lee, A History of Scars: A Memoir (Simon & Schuster: 2021), 50. ↩

- Therí Pickens, Black Madness :: Mad Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke

University Press, 2019). ↩

- Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and

Unmaking of the World (Oxford University Press, 1985), 4. ↩

- Naomi Ortiz in Sustaining Spirit: Self-Care for Social Justice writes in the chapter “Slow Growth,” “what would it be like to focus on the minimums? Those super small acts that have no immediate pay-offs but make a great difference in the long term?”Naomi Ortiz, Sustaining Spirit: Self-Care for Social Justice (Reclamation Press, 2018), 68. ↩

- I am drawing this term from M. Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); and Alice Miller, The Body Never Lies:The Lingering Effects of Hurtful Parenting (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004); as well as Stephanie Foo’s recent memoir, What My Bones Know (New York: Penguin Random House, 2022). ↩

- Davis, The Courage to Heal Workbook . ↩

- This poem was originally written by me around 2003 for my mom while she was hospitalized. This poem was mailed to me by my mother during the summer of 2020, serving as a catalyst for these memories. ↩

- Women, Trans, Femme. This is an acronym used by many cycling groups, in an effort to create a safer space for women and trans people to ride bikes together, away from cisgender men, who often overtake bike shops and cycling spaces. ↩

- This imagery of putting oneself back together draws from Gloria Anzaldúa’s essay “Now let us shift . . . the path of conocimiento . . . inner work, public acts.” Anzaldúa writes about these cycles of trauma, the ruptures, the splitting of self, and the journey to put ourselves back together again (Coyolxauhqui Imperative) as part of the seven stages of conocimiento. ↩