Background

For this reflection for Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry, we staged a dialogue over Zoom to reflect on the Masks for Crips project. Our hope was that engaging in a more informal dialogue would be an accessible way to introduce the reader to our shared practice and collaboration dynamic. Prior to the conversation, we developed questions that we thought would highlight some important aspects of the project. While this project may have appeared similar to other mask projects that emerged during the pandemic, we wanted to use these questions to illuminate some of the unique crip sensibilities and practices that we imbued into this work, and to create opportunities to discuss the ways that care, access, and disability justice were integral to the project.1 When we met virtually for the conversation, we allowed the conversation to unfold organically, each of us sharing memories and reflections that addressed the questions, and allowing other questions to emerge as well. Over the course of the conversation, we realized that many of our memories from the early pandemic were blurry, and that we were uncertain about some of the dates and the order of the events that took place. However, engaging in this conversation allowed us to further care for each other as we worked together to fill in these blanks. As we reflected, we resurfaced memory while also acknowledging that a part of a crip process is being ok with not remembering perfectly. With this in mind, we acknowledge that this is a partial reflection—a snapshot of a moment in time that we want to document to honor the ways that disabled people help each other survive.

Conversation

What was Masks for Crips to you and why does it matter (both on an individual and collective level)?

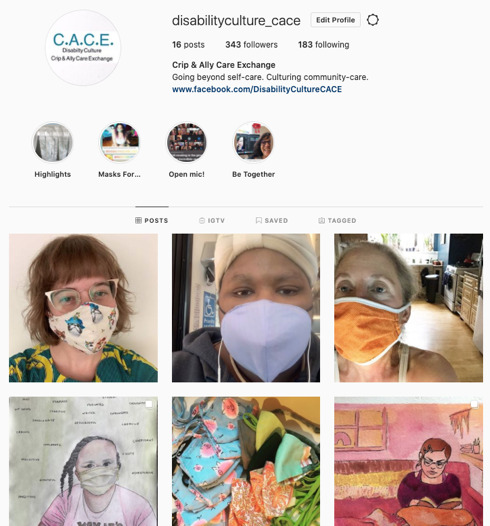

Sandie: At the beginning of the pandemic, I was in the mid semester teaching a Fieldwork class to graduate art therapy students in the art therapy and counseling department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. My art therapist colleague, Katharine Houpt and I initiated a temporary platform on Instagram and Facebook called, “Crip & Ally Care Exchange” for students and disability community members to team up as art-making buddies over Zoom or Google Meet. This platform matched participants and provided ideas for them to make art. For example, one person could rest comfortably, engage in household chores or talk while eating dinner or reading a book, then the other person creates art based on the conversation. They could also create art about each other. The purpose of this exchange was to create an opportunity for companionship and to explore ways to document the human connections during the initial quarantine in the city of Chicago. Participants were invited to share images of their work on our Instagram and Facebook. As the semester came to an end, more mutual aid groups began to emerge in the city. The Crip & Ally Care Exchange platform remained open, but instead of organizing art-making buddies, it was available to support other initiatives, such as Masks for Crips.

Masks for Crips started with shared conversation—sending each other memes and pictures that people were circulating about mask-wearing. We were creating a space for the two of us to vent and make sense of the moment and think through what we could do. Before we figured out what that “something” was, the text messages were a form of being in community with each other from a distance during isolation. It was a place for us to say “Look at this!!!” [in frustration] and also to try and bring some humor into this difficult situation. As we made attempts to contribute or help our friends’ well-being, our communication exchange became a way for us to survive together by being creative while acknowledging each of our capacities to be of service. We were honest about the limitations of the project —we did not want to make anything big and we weren’t thinking this project would apply to EVERYONE. The beauty of it was that we got to practice what it means to center access needs and live into the disability justice principle of collective access. We weren’t trying to operate from a capitalist mindset.

Alison: For me, this project was a way of staying in touch with other disabled people during an isolating and scary time. It was a mutual aid project that tried to fill gaps and address the needs that were not fulfilled by the government or other mask-making projects that surfaced at the onset of the pandemic. Masks for Crips was a way of reaching out to disabled people in Chicago and letting them know that they were not forgotten. And in creating that space, we created a home and practice space for disability justice. It was a space for blending artwork and activism.

Figure 2. Chun-shan (Sandie) Yi, a Taiwanese woman with dark hair and brown eyes, holds a green and blue-striped mask up to her face in her two-fingered hands. There is a speech bubble below her mouth that says, “Hello, there!!!” The image is a still from a film that Yi made to generate outreach for the Masks for Crips project. Photo credit: Sandie Yi, April 2020, https://www.facebook.com/DisabilityCultureCACE.

How was Masks for Crips different from other mutual aid mask projects that surfaced at the onset of the pandemic?

Alison: There were many mask-making projects operating through Facebook and other channels at the beginning of the pandemic that had a lot of people involved and had very high mask production and distribution. But many of these mask groups were making masks for people in institutions and hospitals—as if that’s the only place where disabled people would be—and the projects functioned more as charity. However, we knew there were also people living independently outside of institutions. Filling this need was a part of being in solidarity with that part of our community and supporting interdependence and deinstitutionalization.

Sandie: Exactly. A lot of the other mask projects were developed with healthcare workers and people who live in nursing homes and group settings in mind. You and I have always had the interest in working with people who live outside of the nursing home systems. It was natural that we started noticing that our crip siblings and their care workers were not getting support. I don’t think I was consciously thinking about my [disabled] identity. That was more in the background. It was more about “I want to look out for MY people,” and for practical reasons, we limited this to people in Chicago. We considered people whose labors are unseen, like care workers and PAs [personal assistants] and were thinking, “How are disabled people who are living in the community getting protected?” They weren’t! We could have helped create masks and sent them to mask collection groups, but given the fact that we are both in the disability art and culture community here in the metropolitan area of Chicago, it’s natural that we decided to have a small scale project within our local network.2

What was the role of your friendship in this project and how did you work together?

Sandie: There’s an instinctual and organic quality in the way we work together and it feels like it doesn’t matter what medium we’re working in or what creative disciplines that we are each in. It’s about how we align politically. Sometimes it’s challenging for people to work together, especially if they work in different media. But in this project, we were able to be open about how to let things flow. And that flowy-ness, that space, was the beauty of the project—that organic building process was the highlight on an individual level and a collective level for me.

Alison: Yes! We created a rhythm together with tasks, community engagement, and checking in. For the four month period, we shared consistency and the gift of communication and shared structure. This was meaningful at a time when it was difficult to stay connected to people. Even though we work in different mediums—I am more of a movement artist, and you, Sandie, are more of a visual artist—our political alignment, which started the project in the first place, made it feel easy. Plus, this project allowed us to call on and combine our different strengths. I can’t sew for shit, so I used my other skills like creating systems, access strategizing, and outreach, which allowed you to focus on mask production.

What was the disability community’s response to this project?

Alison: Our friends, supporters of Bodies of Work [a Chicago network of disabled artists], and crip siblings were excited to contribute, and we absolutely could not have done it without their support. There was so much enthusiasm and willingness from our community to provide support through mask-making, mask-delivery, and monetary donations, so we pooled resources. Once the mask orders started coming in, we were able to call on and collaborate with other people in our disability community networks who were excited to contribute homemade masks and offer delivery support. Sandie provided some sewing patterns as options, but we were open to whatever masks volunteers gave us. The range gave us some flexibility, too, to match the mask with the access requests of each recipient. I think in those early pandemic days a lot of us felt really helpless and scared, and so there was a strong desire to be a part of a process and for people to feel like they were building forward momentum. People also seemed eager to make personal connections and stay in relationship, since we were not seeing each other at disability culture events or at school. While we did get several hundred masks out to people, I think the personal level of being in community and feeling like people could contribute meant it was equally as generative on a personal level.

How was disability justice central to this project?

Alison: Disability justice is what scaffolded this project and allowed us to build it quickly. By learning from the work of activists and artists and our crip siblings and elders, we could politically align the project with past projects we knew about [such as Mask Oakland] and build from there.3 I think one of the biggest realizations for me was that at every moment when we had a question about how to manage the project, what boundaries we needed to set to make it sustainable, and what structures would care for us, we looked to disability justice principles and projects for the answers. Instead of taking hours to agonize over decisions, having this support and internalized knowledge allowed us to make decisions very clearly and quickly. It lent this beautiful decisiveness and freed us up for other things. It shows the brilliance of disability justice. For example, when we were deciding if we wanted this to be a Chicago-based project or a wider project throughout the country, we thought about sustainability—related both to our own capacity and the environment—and we knew we had to keep it small and local. When we were worried that the project was not reaching enough people, we reminded each other that a part of working within an anti-capitalist politic—another principle of disability justice—is that our value as people is not determined by productivity, and we needed to keep it sustainable for ourselves and others. It was clear we were bolstered by this practice that was so much bigger than ourselves. And that was profound.

Sandie: Often, disability justice itself may seem to be a philosophy or direction—almost like a dreaming state—and through this project, I feel like I got to practice disability justice in action with you. We got to test it out. Yes, this is disability justice. It’s not about writing or reading about it—we learned and felt it in action. There was room for us to wait and see how we were feeling, to evaluate and reevaluate our access needs, mask-recipients’ needs, and needs of people delivering and producing masks. We allowed our collective actions or strategies to be informed by a commitment to cross-disability solidarity and a passion for interdependence.

Alison: Yes! And like you’re saying, artistic imagination and mutual aid are not mutually exclusive. It’s interesting how sometimes there’s this idea that there’s mutual aid work on one side, and that’s tangible and practical and somehow void of imagination. And then there’s dreaming—more nebulous work that engages our imagination. This was very practice- and resource-oriented in a pretty straightforward, tangible way—get masks to people who need them—but there was still space to dream! There was creativity and a spaciousness in the resource-driven project.

Sandie: Being in helping professions—for example, art therapy—we tend to think about “What is it that I can do for people in need?” but we often don’t talk about “What are the things that I do not need to do, so I can allow more possibilities to take place?” In this process, we were able to free up space and check in with ourselves about our capacity so we didn’t drown ourselves by diving into deep water to help others. I have had so many moments where I don’t feel like I can help everyone and that can feel like I am not being helpful, but I like what you said about the decisiveness. It is about setting boundaries.

How does this relate to your academic work?

Sandie: There are a lot of questions of, “Is this professional work? Personal work? Some service work that you do for community engagement?” For you and I, there are a lot of overlaps, and sometimes it almost feels like there is no boundary. And there shouldn’t be. Because it’s not that we hold this academic position higher than everything else. We recognize that it’s a part of our privilege and access, but at the same time, there’s no hierarchy—the mask project wasn’t higher or lower than our other art or academic practice. We didn’t talk specifically about “we need to practice because we’re writing about it”—it wasn’t an expectation or a rule—but we write about what we practice. And we practice because we write about it, too. For us, the focus is that we recognize this is a space we are in—academia—and our art and activism practice there is tangible. It’s the fabric of our work.

Alison: We are both aware of the ways that disability studies scholars have written about disability justice by engaging with it as a theoretical framework without taking it up in practice. This is harmful and appropriative—it’s not disability justice! It’s important to both of us not to reproduce this pattern as scholar-activists situated in disability justice work. We’ve both been involved in practice-based manifestations of disability justice throughout our academic careers. There was a moment early on in the project when I realized I hadn’t touched my dissertation in a week or two because we were busy with this project, and I started to feel like I was procrastinating. And then I realized, “No, this is the work—it’s not a distraction!” Making that connection was a big shift for me.

How did our own disability embodiments play a role in this project?

Sandie: There’s something unique about masks made by the crip hand. The masks don’t look any different from any masks that other non-disabled crafters make. In my practice, I often make one-of-a-kind wearable items that could only fit one specific person. But in this project, the patterns were created by someone else. The masks I created here would not necessarily show any “crip signature”— unique artistic markings or obvious adaptive design techniques. But by doing this project, I realized that the crip signature took place during the process of making. So the signature is embedded. So it’s about knowing that as I create this piece, I have a specific person in mind, thinking about them and what their fabric or their fashion style may be. In addition, I think about their place in the world at this very moment of time during the pandemic. We couldn’t accommodate everyone, but did the best we could to pick a fabric that would match their personality (if we happened to know them in person) or to stay close to what they requested in their order form. It wasn’t done arbitrarily—we knew many of these people, so in a way it was like the care we put into the project was in the handmade process. “I wish you to be protected. I wish you receive this care and protection” was a message embedded in the project and in each mask.

Alison: A big part of the way disabled embodiment played a role is in the internalized knowledge that we needed to keep access and sustainability a priority throughout. Because we need that for ourselves, and we knew our group of mask recipients, mask production team, and mask delivery team would all need that. And those considerations, that scaffolding, was already patterned for us because of our disability experiences and time that we spend in cross-disability spaces. Someone asked us early on, “How are you finding people to send masks to?” We thought it was a funny question. They were the people in our network! We had personal connections! We were not dropping down from the sky to help “them”, we were checking in with our friends about what they needed. It wasn’t an altruistic gesture. We had built trust through our disability community relationships, and so it was easy to connect to people who needed masks and also to ask for support in outreach, delivery, and mask-making.

How did access play a role in different facets of the project?

Sandie: Access practices were a part of our doing—we provided options, and we knew delivery people would have access needs, too — access is integrated into the ways we communicate already. It’s definitely not like we’re doing this to be thoughtful and from our “good hearts” (this sentiment is often used to describe people who volunteer or work with disabled people). We participate actively in disability organizing and are a part of the community of disabled artists and activists in Chicago, so we wanted to check in with each other, and wanted to know what people’s preferences were.

Alison: A favorite experience of mine was thinking through how to make mask delivery go smoothly. Because we pulled from our community, most mask recipients and delivery drivers were disabled. So, how might we assign routes to drivers who need accessible parking? How might we coordinate communication between a mask recipient who cannot text and needs phone communication and a delivery driver who is Deaf? Are there routes that allow people to avoid downtown or higher stress drives? And something I’ve learned so much from you, Sandie, and also from working with Sky [Cubacub] of Rebirth Garments is that making something accessible and functional and making something fashionable are not mutually exclusive!4 You paid so much attention to different access needs in each mask, but also moved them away from being medical devices, and put care into thinking about the aesthetic.

How do you feel about the project, reflecting on it two years later?

Sandie: It was a short lived project. We weren’t trying to fix everything and knew it was temporary. It was ok for it to be short. Our hope was that we wouldn’t have to keep doing it, because it would mean that people were getting the care and resources they needed. We were not thinking of disability justice as one go-to or method that will save us all. But it provided an anchor for us then.

Alison: In the time of this project [early pandemic], there was a layer of deep fear, but also a layer of hope, that larger society would learn from disabled people. There was hope that we would all get closer together, but I think those disparities have gotten even deeper. Now, it’s still the pandemic and such a bleak moment [January 2022]—we are in a huge surge brought on by the Omicron variant, and hospitals are, once again, full or nearing full. It’s hard to feel hopeful. Disabled people are not prioritized—not by governmental structure or by larger society. Eugenic practices have become illuminated to an even further degree and have sharpened through the pandemic. A part of my interpretation and practice of recognizing wholeness [the disability justice practice] is not forcing myself to feel optimistic or any certain way. You’re a whole person and there’s wholeness in the experience and we can honor the ways we feel, even if the experience isn’t always packaged really nicely with a lot of optimism.

Sandie: It’s ok for us not to be hopeful. And also, disability justice is a hope, in a way, and our process has taught us that we may never know the effects of our practice. Maybe right now we are not hopeful, but maybe that’s just a part of the process. So many people are asking “What do we want to keep from the pandemic?” I hate to end this on “there’s more work for us to do,” but it is true! What I’m thinking about is how do we take a disability justice spirit into the work we create moving forward?

Notes

- For information about the origins, principles, and practice of disability justice, read “Disability Justice: A Working Draft,” on Sins Invalid’s blog at https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-working-draft-by-patty-berne. ↩

- To view the Google form where people requested masks, visit https://tinyurl.com/ymw4ue7p. ↩

- Mask Oakland is an environmental justice initiative that began in 2017 as a way to get masks and shelter to people during wildfires on the West Coast. Mask Oakland expanded its initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic. For more information about Mask Oakland, visit https://maskoakland.org/. ↩

- Sky Cubacub is a queer, disabled Filipinx designer and creator of the accessible fashion line Rebirth Garments. For more information on Rebirth Garments, visit http://rebirthgarments.com/. ↩