When the pandemic combines with personal upheaval, what do we turn to? While safety feels distant and difficult for many disabled people, what small ways do we work to create security in our daily lives? Knitting has been my survival practice for pandemic times. I was knitting for about eighteen months prior to the pandemic, but as my life changed with the pandemic’s onset, I found myself knitting even more incessantly, sometimes even without purpose, knitting something that I knew would later be unraveled. I came to realize that knitting was how I moved through trauma in a way that was in keeping with neurodivergent sensation and meaning-making. Through knitting, I crafted not only sweaters and such, but my own identity as an autistic artist and researcher.

To be autistic is to be figured as not quite there or absent. Autistic rhetorician Remi Yergeau describes this as being thought of as an “absent presence, an embodied state impervious to knowing.”1 This positioning denies autistic peoples’ epistemic capacity to accurately narrate our experiences. Autistic people are then seen as not-quite-human and with our communication “lacking in meaning, purpose, or social value.”2

The stakes of this are significant. Autistic people become visible not as knowing communicators, but as the targets of the cultural “war on autism,” which present the only possible good future as being through the early detection, intervention, and eventual cure of autism—a future in which autism, and therefore, autistic people, no longer exist.3 Autistic people therefore face not only rhetorical absence but also the threat of existential erasure.

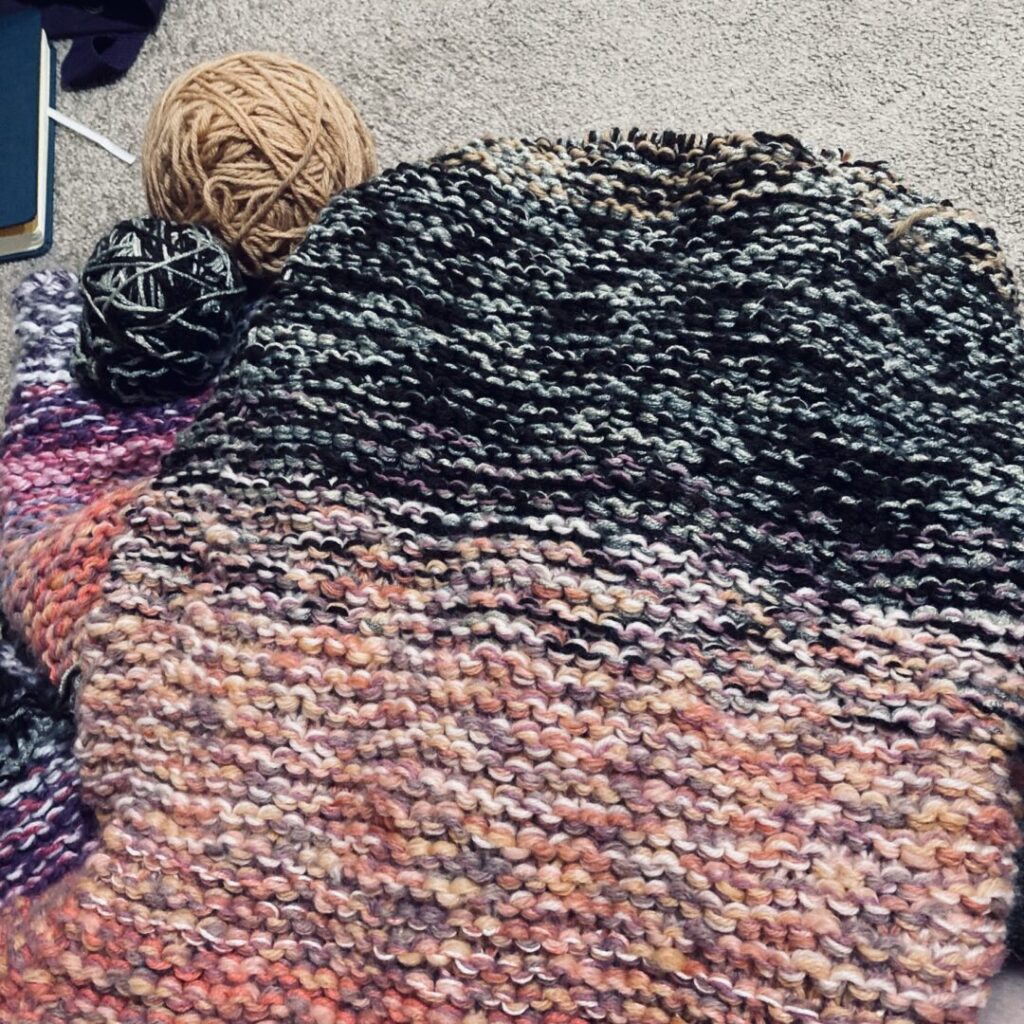

To counter this, I have developed a scholarly-activist commitment to materializing autistic presence in refutation of those who would view autistic and other disabled people as lacking. I believe that not only do we need to tell new stories of autism, but that changing our cultural narratives of autism requires telling these stories in new ways. Knitting is an extension of this commitment, a way of turning autistic experiences into knitted form. One of these projects is this piece, which I title “Security Blanket.”

This blanket is theoretical material. In asserting this blanket as theory, I am arguing that neurodiversity should not only refer to many types of “embodiminds,” but also a diversity of knowledge-making practices, including cripistemologies.4 I turn to cripistemologies to challenge not only what we know about disability but how we know and represent such knowledge, particularly in moments of crisis that might destabilize our knowledge. With thousands of stitches, this blanket evidences the many minor gestures that make up the daily micro-practices we use to make ourselves feel a little safer.5 In the many rows of marled yarn, I find a testament to my continued survivance through ongoing and overlapping crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

My pandemic life, like many people who were fortunate enough to have access to remote work, was marked by staying at home. In this context, I found I was no longer constrained by the portability of the knitting projects that previously accompanied me to campus. I could also keep a knitting pattern open on my screen while I was in Zoom meetings, supporting more complex projects.6 As I participated in the first year of my doctoral program from out-of-state, knitting and my academic growth intertwined until they became inseparable, happening in overlapping crip spacetime.7

In the summer of 2021, my relation to knitting and spacetime shifted again when I began the process of relocating to my university. The move came during one of the lapses in the intensity of the pandemic, but other stressors kept me on edge. As a queer and disabled person, the challenges related to moving were daunting, exacerbating the everyday inequities and pandemic worries, and I found myself wondering how I would make it through.

One day, my body tensed with anxiety, I decided to begin the pre-moving task of untangling my yarn. I had several drawers of yarn that had begun to unwind itself out of its skeins, and a layer of rogue yarn blanketed my closet floor. Reluctantly, I faced the jumble, telling myself that it would at least be a good distraction, and if I wanted, I could take my frustrations out on the yarn by ripping it apart. As I sat on the floor surrounded by these tangles, I came to realize how much yarn I had acquired over the pandemic, how much yarn I would have to find space for in my packing, and just how scared I was.

As I was faced with the sheer amount of yarn that I had accumulated, I decided that if untangling yarn counted as packing, knitting it into something so that it didn’t re-tangle also counted as packing. What started out as a bit of a joke quickly grew into the edge of a blanket, as I started knitting. Over the next few days, I sorted through my yarn, grouping it by color, holding as many as five strands together at a time as I worked my way through a color gradient. When I ran out of one strand of yarn, I simply tied on a new piece, and kept going. However, beyond the logistics of packing, these literal loose ends came to represent deeper entanglements.

I found myself reflecting on the challenges of self-representation, particularly in times of crisis, particularly, when one tends to be denied rhetoricity in the first place. Yergeau proposes that autism queers rhetoric and that autistic people create neuroqueer rhetorics that “articulate alternate spaces and knowledge for inter/relating.”8 Such rhetorics can contribute to and expand cripistemological projects.

Knitting offers a neuroqueer rhetoric, one that defiantly stims and gestures, fabricating autistic existence. This blanket is marked by neuroqueer excess, as moments of feeling too much combined with my piles of yarn.9 Excess, redundance, and intensity are frequent elements of a cripistemology of crisis.10 The material excess of this blanket is odds and ends of leftover yarn, yarn that didn’t quite work out for its originally intended project, and yarn given to me by friends. Not only was the practice of knitting this blanket a marker of my experiences during the moving process, but it became a way for me to acknowledge my connections and past experiences as I prepared to relocate. This excess yarn entangled with my emotions to create a record of me moving through crisis and moving while in crisis.

Neuroqueer knitting, as I have come to understand my practice, is a playful approach to subverting meaning, while insisting that autistic people can, in fact, create meanings of our own. In thinking through this process as not only an exercise in crafting, but as a way to think with(in) crisis, I foreground my neurological queerness. Not only does it mark how my neurodivergence and queerness meant that I experienced crisis in particular, situated ways, but it indexes the epistemological struggle of asserting that autistic communication is valid.

Knitting has a storied history as a form of textile politics—a way of making political commitments material—particularly in relation to gender and queerness.11 While craft is often dismissed as women’s work or considered less significant than fine art, it also has been used as a way to subvert ideas of what counts as meaningful knowledge. Craft is not only a category of objects, but a way of making and doing. As a queer-feminist practice of surviving in an often-hostile world, fiber arts are a vehicle for crafting one’s self and community.12

Through this history, knitting becomes a way to advance a set of ideals and queerly challenge expectations. As neuroqueer subjects, autistic people are frequently denied narrative agency and competence.13 Autistic communication is always already queered, and in further queering autistic communication through craft, I draw attention to types of narratives that are frequently overlooked. Knitting offers a material commitment to neurodivergent cripistemologies through expanding what might be taken as meaningful knowledge making practices.

I did not finish the blanket before I moved. Too large to fit in any bag, the blanket instead occupied the front seat of my car and, later, the second bed in the hotel room midway through the trip, where I lived for a week, doing archival research at a nearby college and completing the blanket. The blanket, even when finished and neatly folded, still refused to be contained in any of my bags, and I triumphantly rolled it out of the hotel on a luggage cart to complete the final leg of the trip.

As much as knitting has been an activity initiated by trauma, the deeper I dive into the theoretical material it provides, I realize it is also an entry point for thinking about autistic joy and crip creativity. Knitting is a sensory activity; it helps me make sense of my experiences.

I approach joy hesitantly. As a Mad person, intense emotions other than joy frequently mark my life. Yet I find excitement in the framework of autistic joy, a framework I encountered through the artwork of Jen White Johnson, who formulates joy as a mode of resistance, especially in the context of Blackness.14 Joy is subversive because experiencing joy is counter to expectations of autism, which is, in foundational medical language a “disturbance of affective contact” and more recent diagnostic criteria includes “reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect.”15 Diagnostic criteria for autism are predicated on the autistic person experiencing distress, and the mainstream logic of autism intervention tells us we should feel fear or anger about autism, certainly not joy. Autism, and autistic flourishing, is at odds with typical conceptions of what a good life can look like.16 Given the cultural logic of autism as tragedy, foregrounding autistic joy has political stakes.

Knitting brings me a type of autistic joy that comes from engaging in a deep passion and sensory pleasure. This joy is not irrelevant to trauma and crises; it is part of how I live. Knitting is not only a mode of occupying space that helps process trauma; it is a way of insisting that as disabled people, we are creative and have the knowledge to move through crisis. As I create by knitting, the steady growth of the knitted fabric indicates that I have, in fact, survived.

Notes

- M. Remi Yergeau, Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 54. ↩

- Yergeau, Authoring Autism, 15. ↩

- Anne McGuire, War on Autism: On the Cultural Logic of Normative Violence (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016). McGuire describes how practices of autism advocacy frame autism as an urgent crisis to be combatted, as well as how these practices position autism as incompatible with any sort of life worth living. ↩

- Sara M. Acevedo Espinal, “‘Effective Schooling’ in the Age of Capital: Critical Insights from Advocacy Anthropology, Anthropology of Education, and Critical Disability Studies,” Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 9, no. 5 (December 20, 2020): 265–301, https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v9i5.698; Merri Lisa Johnson and Robert McRuer, “Cripistemologies: Introduction,” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 8, no. 2 (2014): 127–47. I use Acevedo’s term “embodiminds” to signify that neurodiversity and knitting are experienced in felt ways that trouble a mind-body divide. “Cripistemologies” explores ways of thinking with disability through personal and social experience, while also recognizing that disability itself is an unstable and contingent category. ↩

- Erin Manning, The Minor Gesture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). ↩

- Given the ongoing stakes of remote access as a disability accommodation, it’s important to note that remote access is not an inherently inferior mode of connecting but can lead to generative modes of engagement. ↩

- Margaret Price, “Time Harms: Disabled Faculty Navigating the Accommodations Loop,” South Atlantic Quarterly 120, no. 2 (April 1, 2021): 257–77, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8915966. See also Margaret Price, Crip Spacetime: A Re-orientation to Disability Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, forthcoming). ↩

- Yergeau, Authoring Autism, 86-87. ↩

- Neuroqueer/ing as a concept and practice was coined by several autistic scholars, both independently and in collaboration with each other. See Nick Walker, Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities (Fort Worth, TX: Autonomous Press, 2021), as well as Yergeau, Authoring Autism. ↩

- Theodora Danylevich and Alyson Patsavas, “Cripistemologies of Crisis: Emergent Knowledges for the Present,” Lateral 10, no. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.25158/L10.1.7. ↩

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art + Textile Politics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 7. On the history of gender and knitting, see Bryan-Wilson, Fray, as well as Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (New York: I. B. Tauris, 1989); Beth Ann Pentney, “Feminism, Activism, and Knitting: Are the Fibre Arts a Viable Mode for Feminist Political Action?” Thirdspace: A Journal of Feminist Theory & Culture 8, no. 1 (2008); Lacey Jane Roberts, “Put Your Thing Down, Flip It, and Reverse It,” in Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, ed. Maria Elena Buszek (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 243–59. ↩

- Daniel Fountain, “Survival of the Knittest: Craft and Queer-Feminist Worldmaking,” MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture, 2021, https://maifeminism.com/survival-of-the-knittest-craft-and-queer-feminist-worldmaking/. ↩

- Yergeau, Authoring Autism; Rua M. Williams, “Falsified Incompetence and Other Lies the Positivists Told Me,” Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 9, no. 5 (December 20, 2020): 214–44, https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v9i5.696. ↩

- See https://jen-white-johnson.square.site. ↩

- Leo Kanner, “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact,” Nervous Child 2, no. 3 (1943): 217–50; American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2017). ↩

- Robert Chapman and Havi Carel, “Neurodiversity, Epistemic Injustice, and the Good Human Life,” Journal of Social Philosophy (2022): 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12456. ↩