On a crisp January 20, 2009, across the United States, innumerable inauguration day revelries took place. The celebration at the Lincoln memorial boasted over 400,000 attendees, and the inauguration itself was the most attended in United States history. The President of the United States of America was a Black man, and his name was Barack Obama.

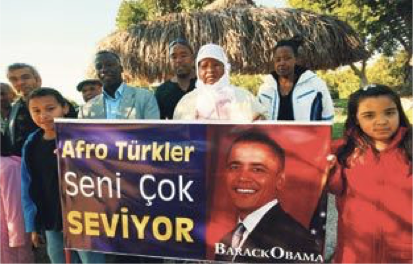

These celebrations were not confined by border or by time. One month after the forty-fourth president of the United States was sworn in, 5,252 miles away from Washington D.C., on the Aegean coast of Turkey, a humble yet fervent series of celebrations were also taking place. Starting February 7, and ending February 9, 2009, the Afrikalilar Kultur ve Dayanisma Dernegi (Afro-Turk Culture and Solidarity Organization, or AKDD) gathered together to commemorate Barack Obama’s election. Though the fête did not receive much attention from the Turkish national news, one outlet did cover the event. According to a report offered by the Turkish Journal’s Muğla correspondent Kenan Gürbuz, signs that read “Afro Türkler Seni Çok Seviyor” and “Seni Muğla’da Bekliyoruz”— “Afro-Turks Love Barack Obama” and “We Await You in Mugla”—were hung up on the insides and outsides of the restaurant.

Gürbuz’s report offers a slight glimpse into the complex ways Turks of African descent simultaneously tie themselves to Turkey and distance themselves from Turkey. His report revealed how Turks of African descent imagine themselves as both of Turkey and of “elsewhere”—of Africa and of Turkey.

In this article, I begin with background on African diaspora scholarship and the nominative challenge of identifying and naming an African diasporic community that sits outside of the traditional purview of the transatlantic slave trade, the primary orbit of African diaspora scholarship. I then move into an analysis of slavery in the Ottoman Empire and how slavery figures into the public and private iterations of African presence in Ottoman Turkey as well as contemporary Turkey. Finally I conclude with a look at the new rituals and rites that have been established by the same communities with which I open to frame this article in order to celebrate themselves as Turkish people who are of African descent and articulate their own vocabulary of what it means to be African descended in Turkey.

Situating African Diasporas in Post-Ottoman Turkey

Recent decades have seen a rise in scholarship that has been centered on exceeding the limitations of geographies, nation-state boundaries, and ethnic and linguistic differences to answer questions of the African diaspora. This scholarship has predominantly focused on the transatlantic slave trade and as such has established a link between Black identity and the African continent. This assumes an a priori “Black”-ness identifiable irrespective of the contexts within which the individuals are situated. While such a connection is not inherently harmful, engaging the geographically specific socio-cultural and historical factors that discursively construct “Blackness” or “Black” bodies within nation-state contexts exposes the specificity of how identity emerges. The representations of Turks of African descent within the context of the Turkish nation-state provides one such example. In this, both the representations that Afro-Turks they themselves make—as in the Afro-Turk Culture and Solidarity Organization’s meeting house above—as well as those caricatures made of them in mainstream Turkish popular culture are relevant. Despite the efforts of Aegean African Turkish communities and foreign researchers, dominant Turkish discourse continues to narrate the presence of “Africans” within Turkey only in terms of recent immigration.

It would be incorrect to assert that the history of Turks of African origin begins and ends with slavery. The point is not to make visible the connection between Turks of African origin and slavery. Rather it is to emphasize that the enslavement of African peoples operates as a framework within societies for which slavery was a regular practice. This metric continues to be the standard frame by which subjects of African descent are remembered. Within the field of Ottoman Studies, the vast majority of literature concerning slavery in the Ottoman empire has focused on Janissaries and Mamluks—slave soldiers taken from the Balkans and the Caucasus through the fourteenth century.1 Africans enslaved in this realm, beyond the occasional Janissary, were the Ethiopian eunuchs used by the sultan to guard the harem.2 Research regarding slavery that is not focused on the sultan’s domestic sphere has focused on the Circassian and Georgian slaves, largely young women, that were brought into the Ottoman Empire by slave dealers for “service” in urban elite harems.3 Analyses of the enslavement of Africans and their forced relocation that did not pertain to the sultan’s personal army or personal harem are far less abundant.

Another factor that complicates research into the presence of African slaves in the context of Turkey compared with the transatlantic slave trade is that the Ottoman Empire was organized according to a framework known as the millet system, which guaranteed the protection of non-Muslim groups by the sultan. This system allowed non-Muslim groups to continue practicing their own religious rites without having to convert. Religion was the primary metric of identification within the Ottoman Empire and subjects were labeled according to religion rather than to origin. In Ottoman archives, Africans also appear according to their religious association rather than their place of origin or race. Such archival documentation is unheard of within African diaspora scholarship of the transatlantic. In that context, subjectivation occurred through place of origin. Esma Durugönül notes that since “African Ottomans and African Turks were considered Muslims and Turks, respectively, they are, virtually statistically nonexistent in the official demographic records of the Empire and the later Republic.”4

Thus, it is incredibly difficult to trace enslaved Africans within the Ottoman world. Sparse research and data pieced together by various Ottoman historians offer an estimated sixteen thousand to eighteen thousand men and women who were forcibly transported into the Ottoman Empire each year during much of the nineteenth century.5 All forms of slavery in the Ottoman world were abolished at the end of the nineteenth century.6

Semantic Figurations of Blackness

Even though the presence of Africans in the Ottoman Empire is not a particularly constitutive part of the Turkish national historiography, the fact remains that Turks of African descent are embodied vestiges of this history. One key element of this embodiment are the semantic designations that have emerged throughout history to refer to those that are considered, for lack of a better term, as “something” “African.” Such terms are siyah, zenci, and arap. Siyah and zenci operate as derogatory terms that specifically refer to the color black (siyah) and black-skinnedness (zenci). Arap on the other hand means Arab. These three terms are often used interchangeably. The distance in meaning between black as a physical color and arap as a group classification—which holds no bearing on the histories of these particular bodies—prevents siyah, zenci, and arap from collapsing into a singularly defined racially “Black” category—despite their so-called positions as people of the African Diaspora.

Recognizing the mobilization of these terms in everyday life helps to illuminate that there is a linguistic and social awareness of phenotypic particularity among subjects within the Turkish nation-state despite a cultural amnesia around how these subjects might have already been incorporated into the national and historical body. In the next section, I provide a visual analysis of three figures performed on Turkish television: Arap Baci, Dadi, and Baci Kalfa, as examples of how the semantic designations used to identify Africa in the Turkish imagination renders itself visible in Turkish popular culture.

Arap baci, dadi, and baci kalfa all refer to specifically gendered work titles which referred to enslaved, as well as manumitted Ottoman African women who were put to work as domestic workers. The word baci directly translates to “sister” and the word kalfa loosely translates to “journeyman.” Together, the words baci and kalfa refer to a type of “sister” or “auntie” figure that took care of domestic tasks and chores within Ottoman homes. Similarly the the title dadi translates to “aunt.”

Arap Baci, Dadi, and Baci Kalfa

In 2016, the Turkish cleaning supply company Vissmate released a commercial promoting the sale of their Dogal Sivi Arap Sabunu (Natural Liquid Soft Soap). The commercial is a thirty-second conversation between an off-camera voice and an arap baci. Vissmate’s Arap Baci is played by Turkish actor Alper Can Aydin. When not costumed to signify the Arap Baci, Aydin’s hair is loose-textured and grey. His body is round and fat and his skin very light brown. To become Vissmate’s Arap Baci, he is covered in what appears to be dark brown—almost black—paint. A black skirt, blue floral button-up, and stockings drape his body. On his head he wears an afro-style wig.

The commercial opens with the off-screen voice saying, “We asked Arap Baci.” As the camera focuses, Aydin’s Arap Baci can be heard responding, “If you didn’t ask me who would you ask, my child? Soft soap is ‘our’ business.” Aydin then opens the top of the soap and inhales deeply, grinning widely as the fumes reach his nose. As he stares at the camera he blinks excessively acting, in a way, that almost seems to suggest that although he is obviously an actor within a commercial who has been hired to act out a part in a commercial, his character is somehow naïve, unaware, and has no prior acting skills. His affectations are exaggerated and his voice particularly high. Unmoving from her position on the couch, Vissmate’s Arap Baci is rooted in the home. She is both domestic and domesticated. Her endearing reference to the off-camera voice as “my child” suggests that she is everyone’s mother. The Ottoman classical music playing in the background contrasts the contemporary position from which the viewers are meant to look, fixing Arap Baci in an always already Ottoman past. This commercial and its construction of Arab Baci presents a cogent visual example of the ways in which blackness in Turkey is imagined.

During Ramadan of 2015, the show Zeyrek ile Ceyrek appeared on Turkish national television for the first time. The twenty-nine part series characterized as an “absurdist Turkish comedy” by its producers was pushed as a spin-off of the famous Turkish television series Filinta. Where Filinta follows the stalwart police officer Filinta Mustafa around nineteenth-century Istanbul as he investigates crimes and falls in love with the daughter of his arch nemesis, Zeyrek ile Ceyrek zooms in on the lives of Filinta’s less adroit colleagues Zeyrek and Ceyrek. In the tenth episode of the series, Zeyrek and Ceyrek’s brother-in-law Sefik develops a crush on a young woman in town by the name of Gulhan. Sefik approaches her in an effort to court her, but much to his chagrin he finds that Gulhan is completely uninterested. Sefik thus devises a plan to convince Gulhan that she and Sefik are meant to be. Upon hearing that Gulhan’s family is looking to hire new house help, Sefik decides to disguise himself as a potential employee, go to Gulhan’s house, and apply for the position with her family. He gets the job. What is of particular interest to my analysis here is the visual signification that Sefik selects for deception.

Onur Yaprakcı plays the part of Sefik. Like the actor Alper Can Adyin in the Vissmate soap commercial, Yaprakci’s complexion is a very light brown. His body is large, his hair a dark brunette. Onur Yaprakci, playing the part of Sefik, disguising himself within the reality of the show as a baci kalfa by painting himself with dark brown (almost black) makeup, padding his stomach to create an enlarged belly, putting on a wig, and covering his head with a headscarf. Sefik spends the entirety of the episode trying to avoid detection as Sefik. I will focus here on the opening scene wherein the viewer is introduced to Sefik as Baci Kalfa. It is of particular interest for two reasons. First, it is the scene where Gulhan’s family is also introduced to Sefik (disguised as Baci Kalfa). Secondly, in the background of the scene sits another Baci Kalfa. However, within the realm of the show, this secondary background Baci Kalfa is not “fake” or “pretending” as Sefik is even though she is played by a male actor.

The scene opens with Gulhan’s brother asking the disguised Sefik, “Where do you see yourself in ten years?” The camera shifts to a dark, almost tar black, matronly Sefik. He wears a white scarf atop his head and a white blouse underneath a large blue sweater. He looks back at Gulhan’s family and responds, “Mutfakta, banyoda, odlarada, yani temizlik ve yemegin oldu her yerde efendim” (In the kitchen, in the restroom, in the bedroom. Or rather, wherever there is cleaning to be done or food to be made). The interview continues. Gulhan’s sister asks, “You are stranded on a deserted island. What three things do you have with you?” Sefik’s Baci Kalfa responds, “Bir tane mandira alirim süt ve süt mamulleri icin. Bir de firin. Eh ekmeksiz olmaz neticede” (A cow for milk, milk products, and an oven. After all you can’t be without bread). Sefik in disguise goes on to add another oven as her final item because you could “never be without too much bread.” Gulhan’s family, delighted by Sefik’s responses, urges Gulhan’s younger sister to show the old Baci Kalfa the door. The Baci Kalfa on her way out is also played by a male actor in women’s clothes, body padded with pillows and painted black. But unlike Sefik, within the realm of the show, that baci kalfa is presumably “real” whereas Sefik is merely in disguise. Therefore the displacement of the previous Baci Kalfa and subsequent replacement with Sefik’s disguise suggests that a Baci Kalfa’s authenticity lies in her capacity to perform a complete domesticity. Gulhan’s family delights in the fact that, in ten years Sefik’s Baci Kalfa sees herself in the kitchen, in the bedroom. She occupies a domesticity that projects itself into the future. Her domesticity is always already ready to be in service. This example is different than the first in that it exaggerates the Arap Baci performance of satisfaction and contentment by being connected to the home. While in the first example, the Baci Kalfa holds in her hands a household cleaning product and demonstrates sustained expertise regarding household cleaning, this Baci Kalfa is accepted because her spectacle of service renders her more real, tying a humanization of her blackness to her domestic availability.

The third and final object under my analysis is the Dadi figure embodied in a 2013 commercial released by the candy company Eti Benim O. The commercial itself is 35 seconds long.

It opens with a shot of a portly figure wearing a dark green dress, a white apron, and a white scarf. The figure’s body is a dark black color that does not quite seem real. The figure is humming, dusting a table in what appears to be a living room. A voice is heard off screen calling out to the figure. “Dadi!” it says. The voice turns into a young woman carrying a packet of Eti Benim O, approaching from some off-screen hallway. Upon arriving at the door to the living room, the young woman pauses, and says to the figure we can now understand as Dadi, “Oylesine mutsuzum ki, seninle paylasmam lazim” (I am sad that I have to share with you). She eats a piece of candy. Moving into the living room, the young woman approaches the Dadi figure. The Dadi attempts to reach for the candy but the young woman quickly pulls it away. The Dadi cries out in a familiarly high voice, reminding the young woman that she promised to share her Eti Benim O with her that day, asking “dadı,gel bugün de benimo’mu paylaşayım dedin mi ha?” The young woman refuses. In exasperation the Dadi figure drops onto the couch, wiping her forehead and crying out “Yoo bu benim alinyazim!” (Oh, this is my destiny). As she wipes her forehead, a streak of black paint comes off, revealing light brown—almost white—skin underneath. For the remainder of the commercial, the Dadi figure chases the young woman around the living room trying to obtain a piece of candy but is continuously denied.

This exchange between the Dadi and the young woman reveals the power dynamics at play in everyday blackness in Turkey that I have been examining. The young woman enters the commercial from off screen. However, for the duration of the commercial, the Dadi figure is confined to the living room. The young woman continuously denies the Dadi access to the Eti Benim O candy even though she had apparently promised to share. In this way, the Eti Benim O becomes a stand-in for pleasures that lie outside of the domestic sphere at the same time that the young woman who brings the candy becomes a stand in for those who are presumed to be deserving of those pleasures, carrying the power to grant or deny access to it. The Dadi figure is denied the pleasure of the Eti Benim O until the very end, muttering even that such a position is her “destiny.” She is confined to the domestic sphere and it is from this sphere only that she is to derive her pleasure. That the Dadi figure wipes off some of her own coloring as part of the commercial suggests that what makes the Dadi believable as a Dadi within the realm of this scene, is not confined to her costuming. The wig, the dark green dress, the white scarf and apron, the dark black body paint, the high voice, and the large padding on the body all animate her as the Dadi. They also animate her position as one fixed to the domicile, as the duster. The one that can be teased with gifts that are never given is what authenticates her as the Dadi. This portrayal of the Dadi figure underscores how Africa and Blackness are made visible in the public sphere despite being rendered invisible in the private historical imagination.

Given that the characters of Arap Baci, Baci Kalfa, and Dadi are all referents that emerged out of an Ottoman history of enslaved African women used as domestic laborers, it might be easy to say that their deployment by the soap company Vissmate, the confectioner Eti Benim O, and the series Zeyrek ile Ceyrek is simply a recuperation of their historicity. But the figurative similarities suggest something else is at play. Yes, Arap Baci, Baci Kalfa, and Dadi all existed historically, but the particular choices that are used to bring them to life within a Turkish visual landscape obliterate their capacity to operate as innocuous historical subjects. The Arap Baci, Baci Kalfa, and Dadi figures deployed in the sites of contemporary Turkish television that I have analyzed here are not enslaved African women used as domestic laborers. They are Turkish men clad in traditionally women’s clothes, adorned in wigs, and painted black. Their sole job it is to take care of the home. Their figuring ultimately reveals the way the Turkish popular imagination cannot make a feminized African figure real. She is forever a caricature whose labor makes the cleanliness and the order and the smooth functioning of a Turkish domestic sphere possible.

In the first section of this article I situated a history of Africans in Turkey within a context of slavery. I demonstrated how Africa is left out of the common memory of Turkish history yet present in the everyday linguistic referents that signal a connection to the past. In the second section of this article I analyzed scenes from three different Turkish popular television programmings—two commercials and one television show. My analysis covered the use of gender transgression as well as the use of makeup to cake each actor’s body in black-colored paint, in order to address how the performance of Blackness on television screens reveals how figures of African descended people are incorporated into the popular screen. By way of conclusion, I turn to a revived celebration brought to life by the living descendants of Ottoman Africans resettled into Turkey. This celebration opposes the caricatured ways Africans are incorporated into Turkish memory by being African Turks doing the work of reviving history.

The Calf Festival

The history of African enslavement in Ottoman Anatolia turned Turkish nation-state is not only instrumentalized by Turkish culture brokers vis-à-vis Turkish television and the multi-media visual space but also by living, alive, African-descended Turkish people, operating in their own right as history brokers. One important example of this is the revival of the Calf Festival. The exact time that the Calf Festival emerged is unknown but what is revealed by the historical record is that it was the culmination of a set small festivities practiced by emancipated Africans in the Ottoman Empire. On one particular Friday, the community would gather together and decorate a calf. They would then make their way to the cemetery and surround the tomb of a person by the name of Yusuf Dede. Here the festivities would culminate and the calf would be sacrificed, its blood collected and placed in pans. Each of those present at the ceremony would then dip their fingers into the pan and mark themselves with it.7 These activities of emancipated Africans in western Turkey continued uninterrupted until sometime between June 14, 1894 and April 22, 1895 when the governor of Izmir, Hasan Fehmi Pasha, banned the festival. The prohibition was lifted the next year but it marked the beginning of increased regulation and surveillance of communities of emancipated Africans in the Ottoman Empire. The festival was completely suppressed by the early twentieth century.

In 2011, Mustafa Olpak revived the Calf Festival in his hometown of Ayvalik, on the western coast of Turkey. Drawing upon his own research, Olpak organized a large gathering of Turks of African descent as well as non-African descended peoples to partake. A series of internet videos document the event from each year that the festival took place from 2012 to 2019. By reviving the festival, Mustafa Olpak mobilized the tools of what might be referred to as “the past” to make present his contemporary existence as simultaneously a Turkish subject, an African subject, and a subject in relation to others making meaning for themselves within a particular nation state. The Calf Festival, as a spiritual practice, as a ritual, as a rite, breaches time and takes up space. Those Turks of African descent who practice, partake in their own way of establishing their relationship to Turkey—one that requires Turks not of African descent to confront the ways they have formulated understandings of who is and who isn’t, what is and what isn’t, a Turkish type of thing. The Calf Festival works to revive not history as past but being as present by calling on the physical presence of Turks of African descent within a specific geography.

Reading the Calf Festival together with the commercial representations of Arap Baci, Baci Kalfa, and Dadi makes two moves. It points to how the visual landscape in Turkey hinders African-descended Turkish people—making monsters out of real enslaved African women that existed within Turkish history, on the one hand. On the other hand, at the same time, this history is being leveraged by Turks of African descent to bring themselves into presence within the Turkish popular imagination. The visual is a powerful place for Turks of African descent to display themselves and create themselves. It is a site of invention and reconstitution. The nuance in the visual rendering of these caricatured figures is understandable only within the specificity of this historical context. It behooves African diaspora scholarship to value this site of identity formation. As I have demonstrated here, discussions of Blackness outside of the context of the transatlantic slave trade provide invaluable foils to mechanisms of identity production—such as race—that are often considered already fully understood. Where we think Blackness is certain and fact, the proliferation of idioms of Blackness allow us opportunities to see otherwise.

Notes

- Both Mamluks and Janissaries were slave soldiers but emerge in distinct times and places. The Janissaries were an institution implemented within the Ottoman Empire in the early fourteenth century under the reign of Murad I and were comprised of an elite cadre of young Christian boys—primarily from the Balkans—forcibly removed from their families and educated within Janissary academies. This sort of slavery can be named slavery that was put in service of the sultan. Mamluk slaves predate the fourteenth century but both forms were abolished by the end of the seventeenth century. Ehud R. Toledano and Y. Hakan Erdem, Suskun Ve Yokmuşçasına İslam Ortadoğusu’nda Kölelik Bağları (İstanbul: Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2007). ↩

- George Junne, The Black Eunuchs Of The Ottoman Empire (London: I. B. Tauris, 2016). ↩

- By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the Balkan wars made it increasingly more difficult to draw Circassian and Georgian slaves into the Ottoman Empire. This resulted in a decrease in Circassian slaves as well as an increase in enslaved Africans being brought into the Ottoman Empire. Ehud R. Toledano, As If Silent and Absent: Bonds of Enslavement in the Islamic Middle East (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). ↩

- Esma Durugönül, “The Invisibility of Turks of African Origin and the Construction of Turkish Cultural Identity: The Need for a New Historiography,” Journal of Black Studies, 33/3 (January 2003): 289, based on Günver Günes, “Kölelikten Özgürluge: Izmir’de Zenciler Ve Zenci Fokloru” Toplumsal Tarih 62 (1999): 4–10. ↩

- Toledano, As If Silent and Absent. ↩

- As mentioned above, the past ten years have seen a rise in scholarship bringing the history of Africans in the Ottoman Empire into public discourse. Scholars such as Ceyda Karamursel, Aysegül Kayagil, and Michael Ferguson have led the charge in this regard. Ceyda Karamursel, “The Uncertainties of Freedom: The Second Constitutional Era and the End of Slavery in the Late Ottoman Empire,” Journal of Women’s History 28, no. 3 (2016): 138–161; Aysegül Kayagil, “Vocabularies of (In)Visibilities: (Re)Making the Afro-Turk Identity,” Antropologia 7, no. 1 (2020): 1–22; and Michael Ferguson, “White Turks, Black Turks, and Negroes: The Politics of Polarization,” Jadaliyya, June 29, 2013, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/28868. ↩

- Michael Ferguson, The African Presence in Late Ottoman Izmir and Beyond (PhD diss., McGill University, 2014). ↩