We need these traditions, not only to know who we are, but to know who we can become.1

Margaret Nelson, the former President and CEO of the Alaska Native Heritage Center (ANHC), made the above statement in Qayaqs & Canoes: Native Ways of Knowing, a 2001 publication detailing a yearlong collaborative boat-building project at the center. The ANHC is a nonprofit heritage center located in Anchorage, Alaska, created to celebrate the cultures of Alaska’s Indigenous peoples, known as Alaska Natives.2 Nelson’s statement demonstrates the perspective that tradition should be instructive and future-oriented, making a place like the ANHC especially important for Alaska Natives. That said, the Alaska Native Heritage Center thrives as a site for non-Native tourists visiting Alaska. For its tourism and traditional teaching functions and the particularity of its founding, the ANHC should be understood as a site of indigenous cosmopolitanism.

Today more than 100,000 Alaska Natives live in Alaska and comprise roughly 10 percent of the state population, making them an important minority population.3 Although it opened to the public in 1999, the Alaska Native Heritage Center was conceptualized much earlier; the center was the result of a decade of planning.4 The Alaska Federation of Natives, the largest and most powerful statewide organization representing Alaska Native interests, approved by unanimous vote the concept for a culture center for Alaska Natives from all over the state in 1987.5 The Alaska Native Heritage Center (ANHC) was formally founded in 1989 as a nonprofit and from 1989 to 1999, the ANHC raised a total of $14.5 million in funds from local, state, federal, and private sources.6 According to its website, “A 30-member Academy comprised of Elders and Tradition Bearers was formed to help guide the Heritage Center staff in program and building design.”7 The current staff members are identified on the website with their name, title, and Alaska Native culture’s name if they are Alaska Native such as “Loren Anderson, Director of Culture Programs, Alutiiq.”8 The majority of the board and the staff—12 of the 14 member board and 13 of the 16 employees—are identified as one or more Alaska Native culture, only one staff member is Native American from outside Alaska.9 From this information, I argue that the Alaska Native Heritage Center was initiated, curated, and is now run by Alaska Natives rather than non-native anthropologists or historians, as is the case for many cultural heritage sites. The center should thus be understood as broadly authored by Alaska Natives.

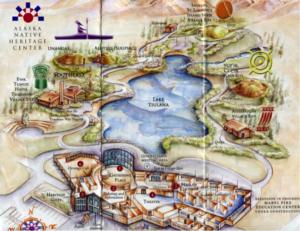

The Alaska Native Heritage Center is an architecturally and conceptually expansive site meant to cater to diverse audiences. The center is open to the public seasonally, typically from Mother’s Day to Labor Day, which is peak tourist season in Alaska.10 It occupies a twenty-six acre site with indoor and outdoor components focusing on history and culture (Figure 1).11 The eleven major Alaska Native cultures are organized into five groups based on traditional territories and lifestyles: Athabascan, Unangax and Alutiiq (Sugpiaq), Yu’pik and Cu’pik, Inupiaq and St. Lawrence Island Yu’pik, and Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian (Figure 2).12 The Village Sites, full-size traditional dwellings of each cultural grouping, take up the majority of the utilized outdoor space. The main building, or indoor component, is composed of a “Gathering Place” for talks and performances, a theater, and the Hall of Cultures (Figure 3). There is also a gift shop to the left of the entrance specializing in Alaska Native-made art and crafts. The main building also houses classrooms that are not part of the visitor experience. They are used for year-round enrichment programs for children from the Anchorage area as well as summer artist residencies and internships for high school students from all regions of Alaska. Despite its breadth and high volume of visitors, the Alaska Native Heritage Center has not yet been the subject of any extensive academic scholarship.13 Its founding did not prompt diverse critical responses such as those that occurred after the 2004 opening of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Washington, D.C.14 The various critiques of the NMAI were linked by some to its location in the capital of the United States15 and its (initially) sanitized, uncritical perspective US history in relation to Native peoples.16 By comparison, the Alaska Native Heritage Center has been discussed relatively positively by a few scholars in the years after its initial opening.

Despite its relatively small population, Alaska is important for its vast size, oil resources, and tourism industry. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline, built from 1974–77, sparked an oil boom in Alaska that greatly increased state revenue and brought some individuals immense wealth.17 Anchorage became the de facto urban center and the recipient of much of the state’s newfound wealth, especially in terms of arts and culture.18 As the state of Alaska is comprised mostly of small villages, Anchorage’s population of nearly 300,000 is over 40 percent of the state’s total population.19 Anchorage should be understood as the cosmopolitan center of Alaska, its major city with many museums and variety of recreational offerings not found in most of Alaska.20 Similar to Robin Delugan’s assessment of San Francisco as an “epicenter of national and international indigenous activism,” Anchorage has become the epicenter of culture in Alaska.21 The Alaska Native Heritage Center has greatly contributed to the cultural tourism landscape of Anchorage and benefitted from its existence, demonstrated by the choice to locate the center in the city, rather than a more geographically central location in the state.

By situating Anchorage, the city, as a cosmopolitan center, I am seeking to situate the Alaska Native Heritage Center as a site of cosmopolitanism, as it acts as a center of living culture.22 The cosmopolitanism of the Alaska Native Heritage Center is two-fold; based on its stated purpose and authorship, the ANHC is a site of indigenous cosmopolitanism and appeals to a kind of cosmopolitan curiosity based on the tourist experience of the center. As there is limited scholarship about the center, I will use my own experience as visitor at the site to consider the ANHC in terms of nostalgia and cosmopolitan curiosity. The ANHC as a site of cosmopolitan curiosity adheres to Natasha Eaton’s term “modernist nostalgia,” meaning, “a return to mythic memory (as opposed to History) and a certain empathy for timeless yet fragile primitive cultures.”23 However, once at the site, the conceptualized timelessness of Alaska Natives is effectively shattered. For my discussion of cosmopolitan curiosity, I turn broadly to Anthony Kwame Appiah, cited by many scholars for his critical work on cosmopolitanism.24 Indigenous cosmopolitanism is distinct from Appiah’s conception of it and has been addressed recently by many scholars including Maximilian Forte and Robin Delugan. To give proper attention to these two strands of cosmopolitanism, I will discuss indigenous cosmopolitanism conceptually and how it is evoked at the ANHC. I will also consider the concepts of heritage and tradition and how they are central to this definition of indigenous cosmopolitanism.

Indigeneity and Hospitality

To many indigenous peoples, indigeneity and cosmopolitanism, which can certainly include hospitality, are intimately linked in practice if not specifically named as such.25 Alexis Celeste Bunten, an Alaska Native scholar and anthropologist, has argued that the ANHC is the major site of cultural tourism for Alaska Native cultures.26 In Bunten’s work, the ANHC is not a major topic, but a reference point for the potential scale and draw of cultural tourism.27 Bunten approaches cultural heritage in part from a Marxist perspective, questioning the commodification of Alaska Native identity and people, yet acknowledges the tangible financial and cultural benefits.28 Her approach does not interrogate heritage, but instead considers heritage as a given for the cultural tourism generally. One of the ANHC’s key terms is “heritage,” and its meaning in relation to the site is fundamental to understanding the center overall. James Clifford, an anthropologist who has written extensively on indigeneity, briefly discussed the Alaska Native Heritage Center five years after it opened, honing in on its heritage work.29 Clifford writes, “Broadly defined, heritage work includes oral-historical research, cultural evocation and explanation (exhibits, festivals, publications, films, tourist sites), language description and pedagogy, community-based archaeology, art production, marketing, and criticism.”30 In this definition, heritage work is wide-ranging and the ANHC engages with many of the activities listed by Clifford. For Clifford, the site is significant because it is Alaska Native-run and not dependent on academic experts and generally, he views the site very favorably.31 Perhaps important to consider is that heritage work does not necessary need to be done by people of the heritage that is portrayed. The first few activities listed, “oral-historical research, cultural evocation and explanation,” are familiar as practices of anthropology. Until quite recently, anthropologists were typically not descended from or related to the people they studied; often anthropologists were Euro-American and studied non-European peoples globally.32

Clifford provides a list of heritage work activities but, within that article, does not deeply consider their impact, generally or specifically through the ANHC. Art historian Nadia Sethi, who specializes in Alaska Native art, has argued that heritage centers in Alaska can “work to reclaim knowledge about Indigenous culture that has sometimes been controlled or silenced by dominant cultures,” pointing to the decolonial possibilities of this heritage.33 Heritage centers in the US, including the ANHC, still operate broadly in the context of the dominant Euro-American culture. Anthropologist Michael F. Brown, considering heritage from an ethical perspective, argues that, “Cultural heritage, whether embodied in places or stories, is a shape-shifting, protean thing whose contours may be contested even by those who create it.”34 Brown points out that the work of a heritage center need not be onerous and that different individuals of the same heritage might have different beliefs about its depiction or study of it. As mentioned above, the ANHC was initially founded as a gathering place for Alaska Native groups, a somewhat modest and insular goal in comparison to its current state. Although the ANHC still serves as a gathering place for Alaska Native peoples’ festivals and events, its activities are expansive and serve an audience of non-indigenous Alaskans and tourists from outside of the state. Heritage as defined by the ANHC, or its founders and current employees, is forward-thinking, bringing these markers of heritage to future generations through education, and historical, highlighting traditional lifeways, beliefs, and cultural objects.35 This concept of heritage necessitates a discussion of tradition, central to the ANHC.

The mission statement of the Alaska Native Heritage Center is, “Preserves and strengthens the traditions, languages, and art of Alaska’s Native People through statewide collaboration, celebration, and education.”36 From this statement, tradition can mean all attributes outside of the languages and arts that characterize Alaska Native cultures, anything from activities to food, song, dance, or clothing. Returning to Sethi, tradition can be conceptualized as “the characteristics that make a culture distinct.”37 A useful definition, provided in the context of Alaska Native art, is that “tradition is the dynamic enactment of values and forms (what folklorists refer to as expressive culture) by all human beings.”38 This fits with Brown’s notion of heritage as protean, that tradition is not static but dynamic. The goal of strengthening traditions rather than just preserving them coincides with this dynamic possibility for tradition. Scholar Ian McLean, who works primarily on Indigenous art, has argued that, “Tradition is only of any use if it is a launching pad into, and a way of engaging with, the contemporary globalizing world.”39 This is a rather negative way to view tradition, but it nonetheless still fits with the ANHC. By pursuing the continuation of tradition through “collaboration, celebration, and education,” the ANHC is using tradition, the specific traditions of different Alaska Native cultures to connect with the larger world.40 The tourism and outward facing components are the major activities of the site, but not by any means its only activity. The focus on language learning and teaching traditional ways of making to younger generations express a belief in the intrinsic value of tradition at the ANHC.

The emphasis of the mission on preservation of language specifically is understandable considering the current demographics of Alaska Native peoples. The eleven major Alaska Native cultures listed above speak twenty distinct languages and of these, seventeen of them have fewer than three hundred remaining fluent speakers.41 Instead of the people “disappearing” or dying out, there is the real danger of languages dying out based on so few speakers. The Language Project at the ANHC is the result of a grant project to survey the language landscape of Alaska and then use this information to connect Alaska Natives in Anchorage with resources throughout the state.42 The ANHC hosts language camps, gatherings held in Alaska Native languages to help speakers and learners utilize these language skills.43 Language learning is a tangible, easily measured way to achieve the ANHC’s goals. Language and its preservation are highlighted in the mission, but traditions and art are equally important and comprise a larger part of the center’s current programs.

Moving beyond the mission of the center, it is worth considering the uniqueness of the ANHC as an indigenous cultural site. The Hall of Cultures aspect of the ANHC is the most similar space to a traditional museum. The ANHC is a highly interactive site emphasizing heritage over history, relating to concepts of museums as cultural machinery. Tony Bennett, considering exhibition practice in relation to difference and culture, states that “museums are best understood as distinctive cultural machineries that, through the tensions that they generate within the self, have operated as a means for balancing the tensions of modernity.”44 Machines can be understood in technological terms as things that make a task simpler, easier, or faster. In this case, the spread of culture, or its preservation and strengthening, can be done more effectively by an institution than individuals or groups. The ANHC is rooted in the place of Anchorage and specifically in its various buildings on its site, so it has the physicality of a machine with its activities rooted in a geographical location. Through its community and school-aged education programs and occasional large gatherings, the ANHC functions as a cultural machine. However, this could also be said of a museum which was not specifically focused on promoting indigenous cultures.

The point of distinction for the ANHC is its role in promoting Alaska Native cultures—which can be seen as a form of resistance to dominant Euro-American culture—through the decolonial possibilities of heritage work. Anthropologist Arthur Mason argues that “today, in Alaska, heritage work has become an integral part of creating a greater sense of Alaska Native self-awareness and identity.”45 Mason is concerned specifically with Alutiiq heritage work, yet his statement demonstrates the importance of heritage work in Alaska. Scholar Moira Simpson argues that the history of Native American resistance to dominant American culture can be traced back to the Ghost Dance movement of the 19th century, a performative, artistic response to colonialism.46 She writes, “One manifestation of this self-determination movement was the establishment of Native American museums and cultural centers.”47 This concept of self-definition has also been considered in response to the National Museum of the American Indian. Amanda J. Cobb described the institution as “[an] instrument of self-definition and cultural continuance,” through its Native American curators and director.48 The concept of an “instrument” of self-definition is especially important when considering the ANHC. Many of the museums Simpson discusses were founded to convey information about Native American peoples not by them.49 Though the non-Native scholars and curators perhaps did research and collaborated with Native people, the distinction of about rather than by is significant. Self-determination and decolonization, though related, are not synonymous. According to Amy Lonetree, a Native American scholar and outspoken critic of the NMAI, to be truly decolonial, a museum would have to acknowledge the true brutality of colonialism.50 The ANHC does in part by referencing in its exhibitions the limited numbers of certain Alaska Native groups and speakers. The ANHC, like the NMAI, does not emphasize the trauma of colonialism, but instead allows a setting for Alaska Natives to present themselves. Like Bennett’s notion of the machine, the ANHC is useful as an instrument of self-determination.

These concepts of the museum, tradition and heritage, foreground the cosmopolitanism of the ANHC, specifically indigenous cosmopolitanism. Many sources point to the seeming dichotomy between indigeneity as highly localized and spatially bounded, and cosmopolitanism, at its roots meaning citizen of the cosmos who is somehow simultaneously above the cosmos. Scholar Elizabeth Povinelli, who has written extensively on Indigenous issues, asks succinctly, “Are indigeneity and cosmopolitanism two different ways of being a citizen of the earth?”51 Povinelli does not conclude her article with an answer to this question but rather focuses on the concepts of ethics and obligations that are required in being a cosmopolitan or an indigenous person. Indigeneity, though necessitating local ties, is a global identification, exemplified by the 2007 United Nations Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted and related to Indigenous peoples worldwide.52 The renewed focus on indigeneity and cosmopolitanism simultaneously have spurred several articles on indigenous cosmopolitanism as well as the anthology Indigenous Cosmopolitans: Transnational and Transcultural Indigeneity in the Twenty-First Century (2010). In this anthology’s introduction, anthropologist Maximilian Forte, writes, “The point is that the idea of ‘indigenous cosmopolitans’ is part of a growing understanding of vernacular cosmopolitanism, that is, real-life, actually lived, everyday practice rooted in specific cultural formations.”53 Forte cites many scholars who have emphasized the highly localized possibilities of cosmopolitanism and how it can be a useful framework for many circumstances of situated relationships and exchanges. In his own contribution to the anthology, Forte argues that tying cosmopolitanism to indigeneity deepens both concepts, allowing for possibilities of understanding the connectedness of the world and of articulating indigeneity.54 For the ANHC, this means not only being a host to the world, but allowing young people and elders to communicate their culture to visitors. Cultural guides at the ANHC are mostly Alaska Native young people. As part of their training, they must learn about cultures outside their own, deepening their conceptions of Alaska Native cultures. Visitors engage in many ways with the ANHC but mostly through these guides, modern young people who live in Anchorage and are trained to present traditional knowledge.

Most articles on indigenous cosmopolitanism use a people, site, or artistic form or style to demonstrate indigenous cosmopolitanism in action, like my positioning of the ANHC as a site of indigenous cosmopolitanism. Mark Goodale, detailing indigenous rap youth culture in Bolivia, defines indigenous cosmopolitanism as “a way of reclaiming modernity as a cultural category and what it means to be modern in Bolivia.”55 Goodale uses the term modern as a counter to the position of indigenous peoples outside of modernity and situating them as modern through the use of rap. His choice of the concept of cosmopolitanism as a starting point is based its connotation of belonging in the world.56 This sense of belonging is indigenous because it combines “an emergent indigeneity with other, more global forms of inclusion.”57 To Goodale, indigenous cosmopolitanism is based in the projection of worlds which can be transnational, regional, or even local and still be cosmopolitan.58 Anchorage, Alaska, and by extension the Alaska Native Heritage Center, can be conceptualized as cosmopolitan in its regional location as well as through tourism, which is mostly intranational though international visitors frequent the site as well.59 Visitors must go to the ANHC to experience a sense of belonging in indigenous culture, but they return to their homes with this new knowledge.

The centrality of the ANHC in culture is paralleled by the Alaska Federation of Natives’ importance in the economic and political realm. The Alaska Federation of Natives has membership spanning across Alaska Native cultures and can be seen as both political and cultural, supporting economic and land rights for Alaska Natives while simultaneously emphasizing its support of institutions and groups that promote Alaska Native cultures.60 Its headquarters are in Anchorage, the major city, rather than Juneau, the state capital.61 Although the Alaska Federation of Natives is political in its aims, the Alaska Native Heritage Center is tasked with presenting Alaska Native culture. The ANHC’s cosmopolitanism functions much in the way Ian Mclean describes the term in relation to Australian Aboriginal flag, albeit physically spatialized. Mclean describes the Aboriginal flag, a symbol of Aboriginality across Australia, as “much more like a cosmopolitan space, a series of localities organized in a network of relations, than a nation. If they have a sense of unity it is not political but cosmological.”62 As a symbol, the flag highlights a different sense of indigenous cosmopolitanism, a sense of belonging in relation to similar peoples, while acknowledging the distinctions between and among them. Similarly, ANHC acts as a unifying pan-Alaska Native identity situated in Anchorage. The term Alaska Native, used to describe several mostly unrelated indigenous peoples in Alaska, and Alaska Native identity’s prominence in an institution like the ANHC suggests that Alaska Native peoples are connected mainly through shared history, based on colonial groupings that have then become means of self-identification, presented to the world.

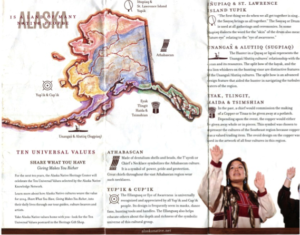

So how does one ethically teach outsiders about Alaska Native cultures? The ANHC provides a potential answer in its “Ten Universal Alaska Native Values,” placed below its mission on its website.63 The values, taken from the Alaska Native Knowledge Network, emphasize sharing, patience, connections, and respect for elders.64 These values like the ANHC’s mission underlie and guide its programs and exhibitions. The anthropologist Susan W. Fair suggests similar but simplified values when she writes, “Attachment to place, sharing, and respect for others are perhaps the most honored of Native values.”65 The repetition of these similar values in statewide publications and organizations suggests their universality in the context of Alaska. By ascribing to these values through cultural activities at the ANHC, Alaska Natives in Anchorage and beyond can have a sense of belonging to a broader Alaska Native culture. The ANHC, a specific place of the enactment of these values through tradition and heritage, can thus be seen as a site of indigenous cosmopolitanism. But the values as described above are not particularly contrary to many other cultures, and they may, in fact, seem quite universal. They are, however, claimed as Alaska Native, placing them into the space of belonging to a group of diverse Native people in the geographic location of Alaska. People of other cultures can be incorporated into this belonging by visiting and submersing themselves into the ANHC experience, taking away new cultural knowledge that is always identified and understood as being Alaska Native, specifically and generally belonging to the Alaska Native cultures.

The Tourist Experience, Cosmopolitan Curiosity, and Nostalgia

My initial experience with the Alaska Native Heritage Center was as a tourist, visiting the site for a day during the summer. I have since been back multiple times on subsequent trips to Alaska. As there is snow and frigid temperatures in Alaska most of the year, the seasonal opening of ANHC allows visitors to fully experience the Village Sites. Separated by region and culture, each Village Site is distinct from non-Indigenous Alaskan or American culture as well as from other Alaska Native cultures. The experience is immersive with a high level of interaction with the cultural guides. Without knowing the Alaska Native founding and authorship of the site, I was initially skeptical, as its advertisements feature mostly much older Alaska Native people in traditional clothing. It takes some digging on the website to understand its founding. The concept of Alaska Natives as guides of their culture could call to mind 19th-century world’s fairs and problematic instances of non-European peoples performing culture for white audiences. This is not the case with the ANHC. Knowledge is shared at the site through personal interaction; by watching performances and having conversations with cultural hosts, high school- and college-age men and women employed by the ANHC.

The visitor’s guide serves as primary document for my discussion of the ANHC experience (Figures 4–6). The indoor Gathering Place is the center of the site, directly across from the main entrance with a large window to view the Village Sites. The visitor’s guide includes a daily schedule for the Gathering Place which cycles through a few different types of performances throughout the day (Figure 5). The four major activities held are “Introduction to Alaska Native Culture,” “Alaska Native Games,” “Alaska Native Storytelling,” and “Alaska Native Dance Performance.” Upon entering the ANHC, one is drawn to the Gathering Place as there is typically a small audience and some type of performance occurring during opening hours. On my first visit, there was an “Introduction to Alaska Native Cultures” presentation followed by an “Alaska Native Dance Performance” (Figure 7). The introduction serves as an overview of Alaska Native cultures—supported by the map behind the stage, color coded to represent each culture—and to the major logic of the site, the cultural richness of Alaska Native cultures, with great diversity yet much commonality. The diversity is geographic, language, and lifestyle-based. The commonality is the shared values detailed above as well as the experience of being Alaska Native. The performances are mostly by the ANHC cultural guides, high school and college students from Anchorage and all over Alaska who eloquently explain traditions, dances, or stories with the skill of experienced docents. They also wear traditional outfits belonging to their Alaska Native cultures.

Front cover and back cover of Alaska Native Heritage Center Visitors’ Guide. 2014. The Alaska Native Heritage Center Museum, Anchorage, Alaska. © 2011.

Interior of Alaska Native Heritage Center Visitors’ Guide. 2014. The Alaska Native Heritage Center Museum, Anchorage, Alaska. © 2011.

Interior of Alaska Native Heritage Center Visitors’ Guide. 2014. The Alaska Native Heritage Center Museum, Anchorage, Alaska. © 2011.

Photograph of Alaska Native Dance Demonstration, Alaska Native Heritage Center, Anchorage, Alaska. 2014. Photograph by Marina Tyquiengco.

I highlight the presentation of the cultural guides as a pathway to discussing modernist nostalgia. The website includes pictures of various employees and cultural guides in traditional clothing, which could serve as a draw for tourists seeking an authentic experience with “real” Alaska Natives. The cultural guides may wear traditional Alaska Native clothing and many speak Alaska Native languages, but interactions with them are much like what one would expect from any museum guide. They are well-spoken and quite knowledgeable. Natasha Eaton’s modernist or imperialist nostalgia is described as a kind of homelessness which makes Others of everyone who is non-Western.66 Eaton’s version of cosmopolitanism is tied to India and the enactment of nostalgia for India in England.67 To Eaton, the exotic becomes cosmopolitan through, “travel and translation.”68 The majority of visitors to the center, especially in the summertime, come via cruise ships.69The Director of Marketing for the ANHC has stated that, “The cruise industry has been involved with the Alaska Native Heritage Center since inception.”70 To conceptualize cruise visitors as agents of this kind of modernist nostalgia is a somewhat literal reading of Eaton. However, the costuming of most employees at the site seems to support this sense that one is receiving or participating in an authentic experience. Visitors expecting guides to perform their culture will not be disappointed, but they will also realize how much the guides are like other millennials, steering the conversation to topics they are especially familiar with and checking their cell phones between visitor groups.

Cruise guests travel as part of their vacation both on cruise ships and to various locations while in port. The size of the ANHC grounds can support the visit of many cruise ship tourists.71 At the ANHC, they can get an immersive experience, in part through the performances which continue each day the center is open. When visiting the ANHC, a cruise guest would come in and immediately be drawn to the Gathering Place, attracted first to the center and then to the performance of culture. Alaska Native peoples to a non-Native American tourist could seem exceptionally exotic and easy to understand through the exhibitions and tours. For many visitors, the draw of the ANHC is likely modernist nostalgia, a cosmopolitan longing for initially unknown “timeless yet fragile primitive cultures.”72 Yet, the ANHC combats this notion by having visitors interact with Alaska Native peoples at the center, where they exist firmly in the contemporary.

Photograph of Alaska Native Games Demonstration. 2014. Alaska Native Heritage Center, Anchorage, Alaska. Photograph by Marina Tyquiengco.

The “Alaska Native Games” and “Alaska Native Dance Performance” coincide with Kwame Anthony Appiah’s definition of cosmopolitan curiosity. To Appiah, cosmopolitan curiosity is about shared experiences among people, interests, or activities that are not necessarily universal but are shared, experienced, or carried out by different people.73 Dances and physical games could serve as two entry points in Appiah’s conception of curiosity. They offer a way for people who are not Alaska Natives to connect with these cultures. This notion of cosmopolitan curiosity is taken from Appiah’s chapter on “Imaginary Strangers,” and it is worth noting that Alaska Natives such as the cultural guides cease to be imaginary strangers to non-indigenous tourists and visitors. According to Appiah, after this cosmopolitan curiosity is enacted, “We can learn from one another; or we can simply be intrigued by alternative ways of thinking, feeling, and acting.”74 Many performed Alaska Native games are more akin to completing difficult physical tasks than to typical sports or games; the main competition is against one’s own abilities rather than an opposing team. My photograph demonstrates one such game, the high kick, where athletes try to spring up from a ground position to kick the ball that dangles from above (Figure 8). It sounds relatively simple, but in the demonstration I watched, an athletic young man could not quite kick the ball. This moment showed the audience that the cultural guides are learning just as visitors learn, but by doing instead of listening. This moment did not detract from the guide’s expertise but rather enforced his humanity—a perhaps unintended, important result of this exchange. The ANHC serves to pique visitors’ interest in Alaska Native cultures by presenting a breadth of cultures and acknowledging that each presentation does not cover every aspect of a culture.

The main outdoor component of the ANHC, the Village Sites, is perhaps the center’s most interactive component. The Southeast region of Alaska is represented by a traditional long wooden house called a Naa Hit in Tlingit. This is one of the largest structures and typically the first on the self-guided tour. Although there is no written record of it, each dwelling is the work of specific Alaska Native groups, initiated and created as a collaborative project of artists and communities. When I visited, the Tlingit house cultural guide, who was of Tlingit descent, explained that each log in the house was set with a series of cuts made by hand with a very specific knife that took hours to complete on one log.75 The dwelling is quite sizable and thus was the result of a considerable number of hours of work. The interior has large carved poles that support the heavy wooden roof. The Tlingit pole is in the typical formline design style, with bear and raven iconography (Figure 9). The guided tour option seemed to provide more general histories while the self-guided tour allowed more time to talk to cultural guides and move at one’s own pace. The Tlingit cultural guide shared an interesting anecdote about her dance cloak. It had four rows of buttons, instead of the typical three rows, as she was related to Tlingit royalty and therefore allowed this distinction. After this visit, I saw many more Tlingit dance cloaks as part of museum displays, and without exception, each had two or three rows of buttons. This dwelling and my conversation with the guide provided me with very specific information that I recalled easily nearly a year later. She shared her sense of belonging to the Tlingit people, particularly through her practice of dance. She showed me an image of her dance cloak on her iPhone. This interaction could be a micro-example of the enacting of indigenous cosmopolitanism, expressing indigeneity through a contemporary medium, accessible in a form visitors would be accustomed to, yet showing traditional culture. Her knowledge interested me and left me with tidbits of information that stuck, but they could have just as easily triggered simple appreciation. Again, as Appiah suggests, cosmopolitan curiosity can lead to learning.76 By working at the site, she was enacting her own kind of indigenous cosmopolitanism, using the job to teach outsiders about important aspects of her culture as well as to learn about and engage with other Alaska Native cultures.

Interior of Main Dwelling of Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian Village Site, Alaska Native Heritage Center, Anchorage, AK. 2014. Photograph by Marina Tyquiengco.

The five other dwellings are all typically overseen by cultural guides (Figures 10–13, Yup’ik and Cup’ik Village Site not pictured). On my initial visit, the Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) dwelling was closed for renovations, but the similar Unangax dwelling was open. The map on the visitor’s guide provides an artistic rendering of the site. Outside of each of them, there are small information panels which explain the traditional names and building methods for each dwelling. The cultural guides are thus not the only sources of information on the Village Sites; these panels and a selection of objects inside also provide information, as in a museum. The cultural guides are typically assigned to dwellings of cultures to which they belong and thus can provide information about more than just the dwelling itself. In my recent visit in June 2018, this was not the case with the Athabascan house. The cultural guide was Inupiaq but very informed about the site, responding enthusiastically when I asked his favorite aspect of the site. He then detailed the ingenuity of Athabascans fashioning rockers out of hanging baby boards. Through the cultural guides, the ANHC is site of living cultures in a way that museums with only static displays cannot really be.77

Although there are typical text panels, the cultural guides are the major sources of information about each dwelling. The information one gets about each site is dependent on the personal interaction with the cultural guides. The guides are well trained and talking to them can be highly informative, but these encounters are highly variable, dependent largely on the questions one asks or how talkative the cultural guide is.

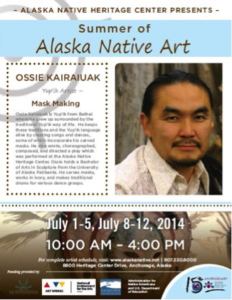

Poster for Summer of Native Art, 2014, Ossie Kairaiuak Artist Residency, 2014. Alaska Native Heritage Center, Anchorage, Alaska. The Alaska Native Heritage Center Museum, Anchorage, Alaska. © 2011

As the cover of the visitor’s guide from summer attests, the 2014 season was the “Summer of Alaska Native Art” (Figure 14). For most of the summer, there were resident artists creating artwork daily in outdoor demonstrations. On my first visit, the artist Ossie Kairaiuak was carving outside of the Qasig or traditional dwelling of the Cup’ik and Yup’ik cultures. Kairaiuak is identified as a Yup’ik artist, and he was in the process of carving when I visited. While carving, he made small talk with visitors, asking them where they were from, before answering questions about his art. He had a tent with several examples of his work. He was carving an ivory mask of a wolf and when asked about his process, he shared that he lets the material dictate what he creates. Rather than giving any specific cultural lesson, while working in traditional materials, he answered perhaps exactly as one would imagine his role as an artist would dictate. The press release on his residency emphasizes his cultural work in terms of song and dance, which he did not talk about specifically. Instead, the tent was like a typical artist studio and visitors to the ANHC were his studio guests. He talked about his art but not himself.

The “Summer of Alaska Native Art” highlights the emphasis on art from ANHC’s mission statement. Art is another example of a shared experience, often cited as a potential source of indigenous cosmopolitanism.78 The artist demonstration and residency program offers interaction with a contemporary artist, which dispels any notion of mythic indigenous artists. Visitors are exposed to another way of interacting in the world, specifically as an Alaska Native contemporary artist. The ANHC focuses specifically on artists who work in traditional mediums, enacting their local or specific Alaska Native cultures. By bringing these artists to the site, however, with its sense of wider belonging, their cosmopolitanism is being enacted simultaneous with their indigeneity.

View of Hall of Cultures Exhibition, Alaska Native Heritage Center, Anchorage, Alaska. 2014. Photograph by Marina Tyquiengco

The section of the ANHC that is perhaps most like a typical museum is the Hall of Cultures which is comprised of installations on the major cultures of Alaska (Figure 15). Unlike the Gathering Place or the Village Sites, there are no cultural guides for this section. There are images of contemporary Alaska Native peoples as well as historical photographs to detail microhistories about each culture. Like a traditional museum, there are objects on display in cases that relate to specific cultures and they are described in relation to their use and meaning for the culture. These objects are all newly made versions of traditional pieces.79 The choice to use primarily contemporary objects is significant as a demonstration of living cultures. Much like the center overall, the Hall of Cultures acts quite opposite of museums by non-Native peoples, made without thought to who created these objects.80 Traditional objects are still valued, but by using only newly made versions, the center can credit makers. This sense of authorship of objects, displaying them with the names of their creators, is unthinkable for artifacts collected much earlier, when the names of these indigenous artists typically went unrecorded.81 After watching performances and walking through the Village Sites, the Hall of Cultures is rather static. Perhaps this is a pitfall of a site that fits so well with the conception of a living culture; its sections seem uninteresting in comparison to the type of unique personal interactions that define most of the experiences of the ANHC.

Concluding Comments

The Alaska Native Heritage Center is a unique site of indigenous cosmopolitanism. Through its cultural guides, it provides visitors with a glimpse into to Alaska Native cultures. It celebrates the positive and mostly apolitical aspects of Alaska Native cultures such as clothing, food, dance, games, and languages. There are still Alaska Natives in poverty, and there is a history of displacement of Alaska Natives like the histories of Native Americans more broadly.82 The wealth of each community is largely dependent on its natural resources, so the equal representation of cultures at the ANHC does not necessarily represent groups’ relative power in the state. The Alaska Federation of Natives and its history suggest that Alaska Native peoples are politically powerful and influential. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 created regional and village corporations, some of which are extremely prosperous and provide well for their shareholders, while others still have not realized profits.83 These native corporations function to profit off the land and resources of specific regions, traditional lands of distinctive Alaska Native peoples, which then benefit those peoples. Some of these regional corporations have provided support to the ANHC. From visiting the site, there seems to be equal attention given to all the major cultures, and it is not so apparent which groups (as corporations are regional) are particularly better off. Very little of the colonial past and history can be gleaned from visiting the ANHC.

The lack of attention to colonial history and past was one major criticism of the National Museum of the American Indian.84 C. Grieg Crysler suggested that the NMAI displays are, “jarringly detached from the larger political and economic realities of the native communities they represent.”85 Similar criticism could be leveled against the ANHC, but it does not aim to be a museum of a people or even a history museum, but rather a heritage center. The emphasis is thus on heritage, culture, and tradition rather than history. The limited context can be viewed as a conscious choice to celebrate culture rather than victimize Alaska Native peoples. A focus on contemporary circumstance might give the visitor a different, perhaps less idyllic version of Alaska Native peoples. But the somewhat benign foci of the ANHC—the dance, language, music, and games that provide the most entertainment to the visitor—also allow the Alaska Native elders who oversaw the initial site to determine how they wanted to be seen, in a positive light through traditions. The longing initially evoked of some mythic past of Alaska Native people, a cosmopolitan nostalgia, is challenged by the ANHC as a site of living culture. Interaction with the cultural guides reinforces that Alaska Natives are a contemporary people, as teenagers with smartphones can show visitors their traditional dance costumes. This evocation of tradition as a contemporary practice is perhaps the most striking aspect of ANHC’s cosmopolitanism.

I came to appreciate from subsequent conversations with Alaska Native peoples in Anchorage, Athabascan land, that the lack of claiming of the ANHC on Athabascan land is striking. This is particularly true for the performances, which often demonstrate Inuit traditions instead of local Athabascan practices. Despite its limitations, the ANHC is a rare example of a Native heritage site authored by Native peoples. Attention to this site can open possibilities to being in the world as a cosmopolitan and an indigenous person, and to relate these ethical ways of being.

Notes

- Margaret Nelson, foreward to Qayaqs & Canoes: Native Ways of Knowing, comp. Jan Steinbright (Anchorage: Alaska Native Heritage Center, 2001), vii. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “About Alaska Native Heritage Center,” accessed on October 2, 2018, http://www.alaskanative.net/en/para-nav/home/. ↩

- Libby Roderick, ed. Alaska Native Cultures and Issues: Responses to frequently asked questions (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2010), 3. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “The Center’s History,” accessed on October 2, 2018, http://www.alaskanative.net/en/main-nav/about-us/centers-history/. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “The Center’s History.” ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “The Center’s History.” ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “The Center’s History.” ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “Board of Directors and Staff,” accessed October 2, 2018, http://www.alaskanative.net/en/para-nav/contact-us/board-of-directors/. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “Board of Directors and Staff.” ↩

- Anchorage.net, “Anchorage Facts and Figures,” accessed on October 2, 2018, http://www.anchorage.net/media/anchorage-facts. ↩

- Anchorage.net, “Anchorage Facts and Figures,” accessed on October 2, 2018, http://www.anchorage.net/media/anchorage-facts. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “The Center’s History.” ↩

- As I will detail below, a few articles on Alaska Native culture, heritage, and tourism have mentioned the ANHC either in passing or as a counter to the main subject of the passage. ↩

- C. Grieg Crysler, “Comparative Alterities: Native Encounters and the National Museum,” in Colonial Frames, Nationalist Histories: Imperial Legacies, Architecture, and Modernity, ed. Madhuri Desai and Mrinalini Rajagopoalan (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2012), 105–136. ↩

- Jacki Thompson Rand, “Museums and Indigenous Perspectives on Curatorial Practice,” in Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives, ed. Susan Sleeper-Smith (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2009), 129–131. ↩

- See Amy Lonetree, “Missed Opportunities: Reflections on the NMAI,” American Indian Quarterly 30. no. 3/4 (2006): 632–645. ↩

- Julie Decker, “1975–1995 and the Post-Pipeline Boom in Alaskan Art: Some History and Personal Overview,” in Icebreakers: Alaska’s Most Innovative Artists. ed. Julie Decker (Seoul: Decker Art Services, 1999), 21. ↩

- Decker, “1975-1995 and the Post-Pipeline Boom,” 21. ↩

- Decker, “1975-1995 and the Post-Pipeline Boom,” 21. ↩

- Anchorage.net, “Anchorage Facts and Figures.” ↩

- Robin Maria Delugan, “Indigeneity across Borders: Hemispheric Migrations and Cosmopolitan Encounters,” American Ethnologist 37, no. 1 (2010): 88–90. ↩

- Douglas E. Evelyn, “The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian: An International Institution of Living Cultures,” The Public Historian 28, no.2 (2006): 55. ↩

- Natasha Eaton, “Nostalgia for the Exotic: Creating an Imperial Art in London, 1750–1793,” Eighteenth Century Studies 39, no. 2 (2006): 228. ↩

- I primarily reference Kwame Anthony Appiah, Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2006). ↩

- “After all, hospitality is inherently indigenous.” Alexis Celeste Bunten, “More like Ourselves: Indigenous Capitalism through Tourism,” American Indian Quarterly 34, no. 3 (2010): 306. ↩

- Bunten, “More like Ourselves,” 290. ↩

- Bunten, “More like Ourselves,” 290. ↩

- Bunten, “More like Ourselves,” 287–288. ↩

- James Clifford, “Looking Several Ways: Anthropology and Native Heritage in Alaska,” Current Anthropology 45, no. 1 (2004): 5–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/379634. ↩

- Clifford, “Looking Several Ways,” 8. ↩

- Clifford, “Looking Several Ways,” 15. ↩

- See Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object (New York City: Columbia University Press, {1983} 2002). ↩

- Nadia Jackinsky-Sethi, “Celebrating Heritage Traditions in Alaska’s Indigenous Communities,” Cultural Survival Quarterly 37 (2013): 4–5. ↩

- Michael F. Brown, “The Possibilities and Perils of Heritage Management,” in Cultural Heritage Ethics, ed. Constantine Sandis (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2014), 171. ↩

- Nelson, “Forward,” vii. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “ANHC Mission and Vision,” accessed October 2, 2018, http://www.alaskanative.net/en/main-nav/about-us/anhc-mission-new/ ↩

- Jackinsky-Sethi, “Celebrating heritage traditions,” 4–5. ↩

- Susan W. Fair, “Traditional and Contemporary Native Art: Inventions, Opinions, Mysterious Disappearances,” in Icebreakers: Alaska’s Most Innovative Artists, ed. Julie Decker (Seoul: Decker Art Services, 1999), 104. ↩

- Ian McLean, “Double Desire: Becoming Aboriginal,” Broadsheet 42, no. 4 (2014): 71. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “ANHC Mission and Vision.” ↩

- Roderick, Alaska Native Cultures, 6. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “Language Project,” accessed October 2, 2018, http://www.alaskanative.net/en/main-nav/education-and-programs/language-project/. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “Language Project.” ↩

- Tony Bennett, “Exhibition, Difference and the Logic of Culture,” in Museums Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations, ed. Ivan Karp, Corinne A. Kratz, Lynn Szwaja, and Tomas Ybarra-Frausto (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 46–69. ↩

- Arthur Mason, “Whither the Historicities of Alutiiq Heritage Work Are Drifting,” Indigenous Cosmopolitans: Transnational and Transcultural Indigeneity in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Maximilian Forte, (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), 78. ↩

- Moira G Simpson, “Native American Museums and Cultural Centres,” in Making Representation: Museums in the Post-Colonial Era (New York: Routledge, 1996), 135. ↩

- Simpson, “Native American Museums,” 135. ↩

- Amanda Cobb, “The National Museum of the American Indian as Cultural Sovereignty Review,” American Quarterly 57, no.2 (2005): 486. ↩

- Simpson, “Native American Museums,” 143–169. ↩

- Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2012), 164. ↩

- Elizabeth A. Povinelli, “Citizens of the Earth: Indigenous Cosmopolitanism and the Governance of the Prior,” in Varieties of Sovereignty and Citizenship, ed. Sigal R. Ben-Porath and Rogers M. Smith (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 213. ↩

- “United Nations, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007,” accessed on February 14, 2015, http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf. ↩

- Maximilian Forte, ed., Indigenous Cosmopolitans: Transnational and Transcultural Indigeneity in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), 6. ↩

- Forte, Indigenous Cosmopolitans, 22–24. ↩

- Mark Goodale, “Reclaiming Modernity: Indigenous Cosmopolitanism and the Coming of a Second Revolution in Bolivia,” American Ethnologist 33, no. 4 (2006): 649. ↩

- Goodale, “Reclaiming Modernity,” 634. ↩

- Goodale, “Reclaiming Modernity,” 634. ↩

- Goodale, “Reclaiming Modernity,” 641. ↩

- Anchorage, “Anchorage Facts and Figures.” ↩

- Alaska Federation of Natives, “About AFN,” accessed October 2, 2018, http://www.nativefederation.org/about-afn/. ↩

- Alaska Federation of Natives, “About AFN.” ↩

- McLean, “Double Desire,” 71. ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “ANHC Mission and Vision.” ↩

- Alaska Native Heritage Center, “ANHC Mission and Vision.” ↩

- Fair, “Traditional and Contemporary Native Art,” 104. ↩

- Eaton, “Nostalgia for the Exotic,” 228. ↩

- Eaton, “Nostalgia for the Exotic,” 227. ↩

- Eaton, “Nostalgia for the Exotic,” 230. ↩

- Cruise Line Industry of Alaska, “Stanley: Support from Cruise Tourism Helped Make Alaska Native Heritage Center a Reality,” February 4, 2015, http://www.cliaalaska.org/2015/02/stanley-support-from-cruise-tourism-helped-make-alaska-native-heritage-center-a-reality/. ↩

- Cruise Line Industry of Alaska, “Stanley.” ↩

- Cruise Line Industry of Alaska, “Stanley.” ↩

- Eaton, “Nostalgia for the Exotic,” 228. ↩

- Appiah, Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, 97. ↩

- Appiah, Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, 97. ↩

- I follow Alexis Celeste Bunten’s approach in identifying but not naming guides specifically, see Alexis Celeste Bunten, “More like Ourselves,” 285–311. ↩

- Appiah, Cosmopolitanism, 97. ↩

- Evelyn, “The Smithsonian’s National Museum,” 56. ↩

- One great example of this is Carolyn Butler-Palmer, “David Neel’s The Young Chief—Waxwaxam: A Cosmopolitan Treatise,” in Indigenous Cosmopolitans, 63–76. ↩

- Clifford, “Looking Several Ways,” 15. ↩

- Simpson, “Native American Museums,” 148. ↩

- Cobb, “The National Museum,” 492. ↩

- Roderick, Alaska Native Cultures, 4. ↩

- Roderick, Alaska Native Cultures, 4. ↩

- Crysler, “Comparative Alterities,” 123. ↩

- Crysler, “Comparative Alterities,” 123. ↩