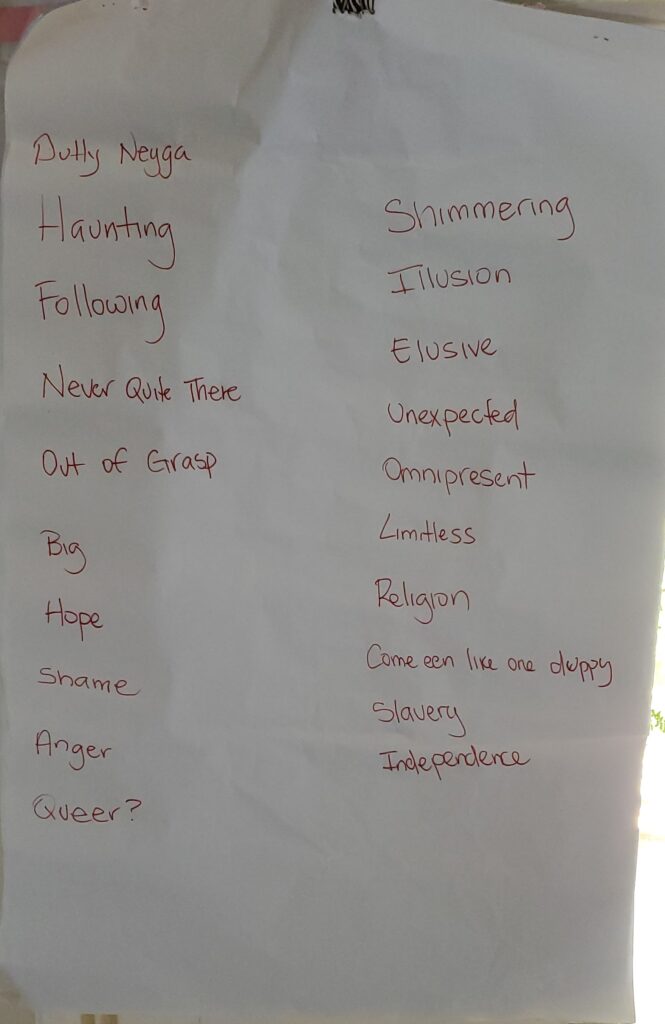

Abstract If asked, many Jamaicans will adamantly state that the country does not have a race problem; rather, it (openly) has a class problem. This series of “meditations on race” explore the tensions of living, loving, and dying in a “paradise” tenebrously held together by the country’s motto “Out of Many One People.” The excursion starts at the feet of an Indian grandmother, the counterpoint against which the writer’s earliest understandings of her own Blackness were formed. Along the way, it onboards and unpacks the experiences of the BlackPoor, the BlackQueer, the BlackWoman, the BlackChild, and Jamaica’s mostly Black diaspora, to grapple with the complex and far-reaching anti-Black reality of colonial and contemporary Jamaica. What does it mean when Black death is so normalized that it redefines grief and an entire genre of music? What decisions must be taken by people living in the chokehold of racism and cultural imperialism, as a matter of survival? And how do even the most intimate aspects of human existence deflate and reform under the pressure of persistent poverty, supported and exploited by the “Global North”? Through prose-like and poetic explorations of the every-day and extraordinary experiences of Black Jamaicans, this piece unsettles the easy equivocation of a majority Black population with a Black-accepting nation. It shifts the façade of “paradise” to explore the depth of its colonial roots. And it amplifies the breathless, relentless question of “should I stay or should I go?” that has haunted the writer and many like her for decades.

Part 1: Jamaica doesn’t have a race problem

Jamaica gained independence in 1962. By 1977 we had entered our first agreement with the IMF. Swapping our old colonial masters for our new “managers.”

– Kill manufacturing

– Deflate the dollar

– And move towards a service-based economy—from producers to providers of cheap labor.

Today that means Business Process Outsourcing, call centers.

Back then it meant, among other things, hotels.

Why not? It’s warm year-round and the beaches can’t be beat.

Did you know that you could only work at the front desk of a hotel if you were light-skinned with “good hair”?

Yes.

Even today the light-skinned girls with the good weave are preferred.

In my mother’s time you couldn’t even work at the bank if you were dark with kinky hair.

Always the smart one, she processed her afro before the interview.

(Nonsense, the bank was run by Black people, how could they believe that?)

Anti-Blackness seeps in, regardless of the color of your skin.

But don’t worry, hotels are equal opportunity employers when toilets need to be scrubbed—skin tone only matters when you must speak to the tourists, not when you have to clean up after them.

Skin tone also counts when you must represent the brand—JAMAICA.

You know the ad?

Light-skinned Indian woman with straight hair emerging from the water, wet red T-shirt clinging to her fantastic frame.

It was so magnificent even Alicia Keys had to recreate it.

Here’s a fun fact, the original model isn’t even Jamaican, she’s Trinidadian. She was selected when the American advertising agency, responsible for promoting Jamaica overseas, failed to find a “buxom and voluptuous Chinese Jamaican girl” who would capitalize on Americans’ growing interest in China by luring them to an Asia closer to home.1

Think of it as “West Asia” . . . kind of like the “West Indies.”

History repeats itself.

Sintra Arunte-Bronte is gorgeous and her 1972 poster put Jamaica on the map and became a collector’s item.

She certainly doesn’t look like the majority of Jamaicans.

(That’s kind of the point of the campaign.)

The advertisement certainly doesn’t represent Jamaica’s mostly Christian, sexually conservative culture.

I mean, sex work is illegal, and the gyrations of dancehall are considered lewd and improper, so what are we selling here?

For now, let’s just treat the law as a story countries tell about themselves to other countries, as opposed to any kind of fact.

. . . The same way anal sex (interpreted as homosexuality) is illegal in Jamaica, while queer Jamaicans continue to shape Jamaican culture both locally and on the world stage.

. . . The same way abortion is criminalized but there’s an entire ward, in a government-run hospital, dedicated to caring for women suffering the complications of illegal abortions.

Jamaica’s laws are a (British colonial) story we use to project what we’d like to be, rather than what we are.

Sun, Sand and Sex is what keeps Jamaican tourism moving—and that last S keeps many Jamaicans alive. When minimum wage is US$85 per week, you have to sell something else to survive. Love is only free for people with generations of wealth behind them. For the rest of us, it is a tool: to eat, to have somewhere to sleep, to send our children to school with the hopes of something better. Besides, Jamaican penis is a whole brand unto itself, and Rent-A-Dreads are at a premium, a holdover from slavery when Black men were hypersexualized studs.

But, let us keep to the present.

And the ad is sexy.

And even if she doesn’t look like most Jamaicans, she does look like some.

Because we are a melting pot of African, English, European, Asian, Syrian, and Indigenous peoples.

Except, much like the processed cheese we enjoy with our version of hot cross buns at Easter, it never quite melted.

The Africans and South Asians who came over as the enslaved and indentured servants are still more likely to be poor and working class, while the Asians and Syrians that came over as merchants and businessmen float somewhere between the middle and the top. That’s to say nothing of the English and European people who either owned slaves or showed up with enough money to become land barons or merchants themselves. They were the forerunners for the Spanish who have returned as hoteliers, building thousand-room resorts on beaches that used to be free.

Now locals must pay to touch the Caribbean Sea, and the government is okay with it.

And we’re all still here. Melting. As climate change rocks our small island developing state, and the big countries in the Global North live in air-conditioned luxury.

We are here, melting together(ish), in Paradise.

But Out of Many One, right?

The country’s motto: “Out Of Many One People”

One what?

One thousand four hundred and ninety eight murders in 2022

One hundred and four people killed by police officers on active duty that same year.

Fifty police officers killed in the last year.

(But that’s not a race problem, they’re all Black there.)

No, we’re not.

And you know it.

And you like it too.

You only have to look at TikTok to understand.

The “exotic” white girls with the Jamaican accent reach 500,000 views every time they say bumboclaat.

While little Black children are punished in school for speaking their mother tongue.

“Slave language.”

“Backward.”

“Patois has no place in the thinking man’s vocabulary.”

Patois is what happened when the enslaved mashed all their languages together and used them to beat the English, that had been forced onto them, into submission.

And yet, it is still treated as a marker of ignorance—too African, too Black—while Nicki Minaj peppers her songs with it to rounds of applause.

Parents’ lips quirking upwards as their children sound like cast members on Peppa Pig and Cocomelon.

Anything is better than sounding like you were born here on the Black backward salty rock that somehow fascinates the world.

*Whisper* (Jamaican boys are failing exams because they refuse to learn English. They think it’s too white, and for them white = feminine. English is for girls, real men speak patois. Real men are Black men.

Jamaica, to the world.

We aren’t all Black

But . . .

Where are the white people in the jails?

And where are the white people being gunned down by the police ?

Where are the white police officers being gunned down by criminals?

Overwhelmingly the people dying seem to be . . .

Black

Black (and poor)

Perhaps in Jamaica, both are the same.

Perhaps our class problem is deeply rooted in race.

Black

When the news cameras capture the mothers crying for justice, screaming that their sons were good boys.

Black (and poor)

“Mummy say sonny, nuh bother wid di copper. Me never listen but it never matter, from you is a ghetto yute dem have yu as a shotta, my badness and me mother prayer mek me deh yah”2

Obviously, they weren’t all good. But who could be? When generation after generation of grueling work and poverty is all your family has to show for itself. When it’s impossible to fully grasp the exploitation and abandonment by the state.

How long can you see violence against people who look like you before you learn to be violent to people who look like you?

(Black)

When the daughters come up pregnant at fourteen

Black (and poor)

“Almost half of all sexually active females in Jamaica between the ages of 15 and 24 years old were forced into their first sexual encounter.

The same is true of 16 per cent of adolescent boys between 10 and 15 years old, as they did not consent to their first sexual encounter.”3

They’re forced into sex, and forced to have sex for things.

Age works differently here, but you may already know that.

Did you know that some tourists believe that the Caribbean sun makes girls ripen faster? Like fruit. So thirteen years old here is the equivalent of eighteen in the States. Bet you they don’t pack that truth in their suitcase. Just a red, green, and gold shirt with “Jamaica No Problems.”

Mango gyal, spoiled, left to rot after your departure.

When the men make songs about killing each other that stay at number one for months and turn them into millionaires.

“Skeng and Tommy Lee Sparta’s Protocol holds the number one position, based on YouTube views (46,329,405).”4

Have you ever heard “Protocol”? It goes like this:

Hey boy, don’t ramp with the shift

People we kill

Bomb brain bleach a you yard with a bill

Stuck the lass in a him chin, yow, a evil graphic, no

Fully yeng-yeng and breach the traffic

Man psychopathic, now light up a spliff

Now, gunman me will kill the granny

Diss me, dat a me,

me no left nobody

Ratty Spartan, man dark up the shift

An ode to murdering the Black (and poor).

It’s not that life doesn’t matter here.

It’s just that Black life matters the least.

How did we get here?

(On a boat! Ha! Too soon?)

Too soon.

Part 2: My Black Is Indian

It may seem strange to start a mediation on anti-Blackness in Jamaica by mentioning my Indian grandmother, but here we are so intertwined that it is almost impossible not to. My first understanding of myself as Black came from being the Black child of a half-Indian woman living in an Indian community.

My grandmother was born on a boat coming from India.

Married at 8.

Separated when her father-in-law hit her with a stick for failing to produce a child.

She had my mother with a dark-skinned maroon man.

He wasn’t around. Many fathers are not around.

My mother learned to speak Hindustani so she could understand what they were calling her.

The Black one.

Hair curled too tightly whereas my aunt’s could not hold a clip.

The Black one.

Skin too dark even though she was lighter than my uncle.

But he was a man, and his father was Syrian.

The little Black one.

My mother watched my grandmother die.

After eighty-nine years of making us milo to drink and fixing us sandwiches while we studied.

After baking us roti and teaching me how to sew.

After peeping through my door to pray for me and make the sign of the cross while she thought I was sleeping.

She died in my mother’s house while my mother shrieked and howled a mix of grief and something else. Something . . .

My mother, the little Black one.

And who am I?

I am the child my mother had with a man the same coal-black as her own father.

The only daughter in a world full of sons.

I was the one holding my pale skinned fine haired grandmother as she took her last breath.

I am Maragh Moore Lindsay Williams.

I am slavery indentureship sugar plantation orange orchard bridal jewelry pawned to start a shop estate overseer on white horse anything too Black nuh good I love you me baby.

In the Caribbean we are haunted by death, duty, decisions, departure, and delusion.

Everyday, something else to do or choose, someone else to save, and the pontification of some obvious delusion that demands that you tek bad ting mek laugh, and someone to tell goodbye.

The earth is good here. Our products are “organic” by default. We are brilliant by all world standards. But it’s hard to grow with the weight of colonialism around your neck and leaders who learned too well from those who left.

Death.

Duty.

Delusion.

Decisions.

Departure.

DEATH

The specter of death haunts most Jamaicans daily. Our news programs are often headlined by shootings, stabbings, or houses set aflame. It is a quiet weight that settles on us, sits beside us as we drive. Causes us to scramble for the phone with heart in chest when somebody calls after 10:00 p.m. Becoming desensitized is almost a matter of survival. Being hypervigilant is the norm. How to avoid death? Who controls death? And what you must do to get your children through safely—to the other side of twenty-three—the age at which you’re considered an elder in some communities because so few make it there? How much must you bend them to ensure somebody else does not see them as something to break?

Black Pickney Must Be Obedient

November 26, 2016

black pickney must obedient

especially when being raised on a median behind a crate of box juice and sugar buns

tying grass to lizard tail

while her mother dodges sun rays and groping hands from car windows at the stop light

one misstep is bawling tire and red-red blood

white shirt with rainbow pony flying out behind child falling

nobody remember next week

poor black child

the negro child must listen the first time

especially when under the sunset of light blue eyes

cane piece burning mellow in the back

while his mother swallows the bile in her throat because missus looking at her child playing where him nuh supposed to play

one more step and is her hand that inna him back a grab him

whip inna him skin like dirt path through bauxite country

nobody charge her fi the body lidding flat unmoving mark up like map

this a the third child this year

not my child5

who cyan hear must feel

especially when your mother told you she had a bad feeling in her stomach

cooked you macaroni and chicken to make you stay home

flipping through photo albums with you, telling you the same stories again and again

she heard the ambulance as sure as she heard you crack the chicken bone and chew it to ash and spit

no real reason for the hot lead merging with your spine

save for your face . . . the skin of it . . . the thin of it . . . hungry nigger

nobody guilty really, just the cost of the thing . . . the safety of us all

you will lose some along the way

nobody calling his name outside of the internet and they’ll soon grow weary

or another nigger will die . . . on Facebook

her one boy child

the black child must be broken for their own good

especially when they’re bright . . . precocious is a characteristic for the white

facetious enough to feel they have the right to speak to people like dem a size

like they are equally human

the safety of the black child depends on their ability to act like they aren’t there

to hide in storage closets while their mothers clean used condoms from hotel beds, no wrapper

to say yes sir and no sir as people speak in their face, close enough to feel the spit, loud enough to shake them

to always appear exuberantly grateful even when being handed things that are rightly their due…even when they had to work double hard for it…even when they broke their backs

black invisibility is survival

a damning skill for a black child

we will lose more along the way

nobody remembers anything but the audacity (pass dem place)

the courage (bring it down pon demself)

the death (as one gone a next one born . . . me gone me have work a morning yah)

another nigger pickney

just another child.

DUTY

The irony of living in paradise is most of us work too hard to ever fully enjoy it. And relaxing on the beach in the blazing sun with a piña colada in hand is very different from serving that piña colada in black dress pants and a cotton button-up shirt for 12 USD per day. Until you have to mix cement at nearly 100 degrees. Until you have to cross the burning hot sand with worn down shoes on your feet to sell cowrie shell jewelry to wary tourists while security guards chase you away. But we do it, because we must. And yes, sometimes we go with our families to other beaches, and there—the warm and glorious sun, our beautiful country—we enjoy it.

The Sun Is Wonderful Until You Have To Work In It

June 27, 2016

the sun is wonderful until you have to work in it

you come here to tan

while we sweat in embassy lines hoping to go there and get a job in a/c

i have watched one side of my father’s body grow darker and darker as he sat in his taxi day after day waiting to earn minimum wage.

i do not need anymore sun

i guess how you feel about it depends on how happy you are to see each coming day

happy, not grateful

at the feet and under the back-hand of our grand mothers

who have finally aged their way to the front of the church

we learned to be grateful for life

no matter how unlivable

to judge the people who choose not to continue here

while giving praise to Africans who swallowed their tongues or hurled babies into the hungry sea

the sun has never protected us

your mama raped under its indifferent glow

just as she was pushed out under it’s setting

with no fanfare

another baby with nowhere to hide under the burning sun

you go to our beaches and lay out like lobsters

while we serve you food and drink

you tell us how lucky we are, while forgetting to tip, life in paradise is all-inclusive you see, and you already paid too much to be here, but it’s all worth it because of the sun.

i suppose the sun is quite beautiful when you choose when and how you take it

when your days are more than walking the stop light median with donuts and car chargers and orange hung in a box around your neck.

when your real life is lived in the shade the sun is a welcome respite

but we have always been pushed out before dawn and gone home well after dusk

the sun-light hours are just another part of the day for us

who work regardless

and see no rest even when it goes

breathing hard into phones and cleaning office bathrooms while our babies sleep across the road with a woman we kind of trust

but kind of know we can only leave them with while her boyfriend is away from home

you think these things are because of the night? no.

it has always been dark for us

under the glare of your gaze and the cloud of your expectations

a blackness from which the sun has never saved us

despite burning us mercilessly

DELUSION

One of the things I love most about Jamaicans is our approach to nicknames, especially rural Jamaicans and those from low-income communities. It’s neither politically correct nor particularly considerate of other people’s feelings. But we understand it in a way you only would if you were raised here—there is no malice behind it. If you are chubby your name is Biggs, if you look South Asian, your name is Indian, and if you are light enough your name is “White Man” or “Reds.” Despite the presence of “Reds and White Mans” in the ghetto, there are very few Caucasians. I think about this every time somebody says Jamaica doesn’t have a race problem. Because if we didn’t, shouldn’t Black people be equally represented among the wealthy and white people equally represented among the poor?

Why Are There No White People In The Ghetto?

February 25, 2017

why are there no white people in the ghetto?

since Jamaica nah nuh problem wid race

and the whole a we a one

weh di white one dem weh a live inna di prison dem well far from the sun

or else sell chamois a day time pon the donkey jaw bone of the equator a bleach til dem black

or dem peach

or pink or khaki or speckled like di back a old people hand

why are there no white people in the ghetto?

We are a proud multicultural nation

(but weh bout the nuff a we weh black!)

we have a rich heritage, a veritable meting pot

(but wah bout we weh bwile out fi gi body to di soup)

we are among the most awarded beauty queens in the world

(so why dem nuh look like the most a we!)6

Jamaica land we love

(no weh nuh better dan yaad) . . .

statistically

i mean

logically

i mean if yu really pree

the country supposed to mek up equally

across all a di parts

right?

right?

since we only problem is class

so why when me see thin nose straight hair light eye

me just know me a look inna one rich face

why dumpling and butter only pass thick lip

and digest inna dark brown belly

behind di ring a fat weh rest down over the fruits weh sell a market

or back a di ribs weh lift cement a day time

why?

why are there no white people in the ghetto?

and why we allow it?

still buy them face cream weh di woman nuh even look like we

still beg off Mr Brown X amount a trust fi him goods

but pay full price plus tax to di man wid di Syrian name we cyan pronounce

why we still teach we pickney dem fi talk soft to fi dem children

who younger dan fi we

as if we a prepare dem from early

fi sell inna dem wholesale

as if even before dem born

greatness inna dem DNA

and fi we full up a failure, or at least impending poverty

struggle inna we blood

di whole a we a one

di whole a we a one

out of many one people

di whole a we one

so how come

how come

how come

there are no white people in the ghetto?

DECISIONS

For many Jamaicans, the decision to stay or migrate is on a constant loop playing in the back of their minds. It’s estimated that as many Jamaicans live outside the country as in it. And there is a running joke that no matter where you go, you’ll find a Jamaican—often wearing Jamaican colors at that. It’s complicated, many of the people who remain do it as a labor of love, an investment in the country that they know will cost them in the end. When I was at school in Canada I went into a cookshop to buy food and the man serving it waved the spoon and warned me I should never go home, because anywhere was better than Jamaica. He said this while standing in front of a Jamaican flag and serving curry and oxtail, happily dancing to reggae music as he dished my meal.

The Unbearable Burden Of Blackness

October 26, 2016

the unbearable burden of blackness settles itself on my chest and spreads around my rib cage

it compresses my lungs until i exhale the conspiracy

i am thinking about leaving

this place

home

the thought of leaving is the crease that has appeared by the side of my nose

and the haunt pacing just above my floors at night

i know that if i leave i walk backwards across the sea

following the trail of unpaid money and labour for free

i complete the story about my country and people like me:

nothing good can stay there

even the sugar had to leave

i do not want to tell this story about my country.

staying starts to feel like a waiting

to die

at the hands of some young poor black man who never knew me

to die

bitter and unaccomplished but grateful to the Lord for long life to know sufferation and worship

to die

years before my body is in the ground as a matter of survival

to die

watching the people who have it worse than me

die.

the black country is no place to live unless your family is newly black or only slightly black affiliated

the enormity of the colour makes no difference to its place

we are still niggers here

i grow tired of the breathless feeling that introduces me to each day

the knowing i am already late by over 200 years

i’ll never catch up

but maybe if i leave i can catch on to the what-leff of the good life over there for me

i was born an existential crisis and three decades later it has worn through it’s teeth on me, and i my muscles on it

i wake up wondering where to be black since i can’t avoid it

perhaps to be exoticised

anything but this giving up my soul for the sake of being home

no part of me wants to leave

i am awake again

the load has crushed my lungs and ripped me from sleep

today i must go to work and in between the things i must do that they never pay me for

i must think again and again

stay or go

thrive of survive

give in or resist

the burden of blackness

DEPARTURE

Often, there are things in life that we think are universal. Love being one of those things. But love is very different and calls one to do . . . unique things . . . when one is living in poverty and in the developing world. When the steadiness of love must somehow follow the ever-moving black body. When love is a tool to change nationality. Love for love’s sake is often for the rich and the white—but even they may marry for power and politics. When death is at your door and there are five flights to Miami a day, separation and survival intertwine . . . lovingly.

Separation Anxiety (Life In The Third World)

June 16, 2016

The truth is, if you live in the Third World, near permanent separation is always a moment away.

Not because we love differently

Not because we lack consistency

But because when the ships left the planes remained.

We are raised in the shadow of impending goodbye.

We are always mobile here.

I wonder if people from big countries with money know what this feels like:

The settling like the interlocking of teeth when you finally know you will leave your baby behind to be raised by strangers who will hopefully be good to her.

Because there is no money here, and no jobs.

Because she will need uniforms and food and a chance better than you were given.

And the only way you can do that, is to leave her.

To pray her away from the grasping hands of neighbourhood mans

To listen as she grows less interested in talking to you and calls her auntie mummy.

To always remember her three years younger than she is because that is when you last saw her

When you are raised in the Third World family is a thing that convenes around weddings and funerals.

Your grandmother marks the pages of her Bible with a scratched off phone card and calls your absent uncle by his full name.

Nephews visit with foreign accents desperate to learn how to climb trees and talk like you.

You wish you had half their clothes and even a quarter of their freedom

They always seem younger than you were at their age though they are all bigger than you.

Your sister has a passport that lays the world at her feet, you cannot enter her country with yours.

These are the choices we make here, in this place.

When you love in the Third World the soft edges come off and are replaced by steely determination. The softest loves are saved for people who have had full bellies for five generations back, and halls lined with college degrees. Here, love is a thing that bends and extends across seas.

Fidelity means ‘he sleeps only with his wife from the business marriage and me’

Commitment is two trips to western union per week and another woman wearing what should have been your last name.

Next month he will send for your son. He has told his wife his boy is being raised by his grandmother. Even American public school is better than what we can get for free here.

When you learn in the Third World you understand that the people learning alongside you are birds in mid flight. They will not be here long and neither should you, if you are smart. Even if you are not smart you should try to be accomplished. Your 10 year high school reunion will most likely take place in Toronto and three quarters of your class will attend, married mostly to girls from the school down the road from yours. Home is a place you do charity for, snow bound kindness for a hot world.

These are the choices we make here, and the things we do to survive.

It is still life, we just do it differently. Togetherness is a privilege reserved for the few with enough land to house their kin and enough money to keep them safe.

For the rest of us . . . apart is a simple conversation and a nodding of heads. Nothing is promised in this place. Forever together least of all. Sundays are for phone calls and the other days are work. It takes money to live and our countries have none.

Final Thoughts

I’m writing this final paragraph from St. Elizabeth (St. E or St. Bess), a parish on Jamaica’s south coast.

St. Elizabeth produces a significant amount of Jamaica’s fruits and vegetables and is one of its least “developed” spaces. Lots of boutique hotels run by expats. Burning hot sun and rocky seaside. Strangely some of its terrain looks very much like the plains of the Serengeti.

St. Elizabeth is also home to numerous light-skinned, blue eyed, low-income Jamaicans. As history has it, a Scottish ship capsized on a reef just off the coast and the sailors swam ashore and settled. They mixed with the indigenous Taino people, and later German settlers, creating the light eyed, freckled,”Red” people who are more populous in the area than any other in Jamaica. Another theory is that in the past, mulatto and quadroon families intermarried for years to maintain their light skin.

I am in St. Elizabeth to facilitate a workshop on gender-based violence and decided to add a day for my friend and I—another Black woman who works in social justice—to rest.

As the boutique hotel’s British owner smiles at me, and the white Portuguese general manager makes witty small talk, I am reminded of the novelty of rest for Black women like us and the fact that my presence in this space was made possible by the staggering rates of gendered violence in Jamaica. One in three women will experience intimate partner violence in her lifetime, but we suspect it’s more like one in two because when men lack the social and cultural resources they’ve been told they should have as men, their pursuit of masculinity plays out on the bodies of Black women, other Black men, and themselves.

Looking out over the dry yet green terrain, this is my own haunting and hope. Haunted by the persistence of anti-Black violence.

Hopeful for a life of rest.

Exhausted by the pursuit of it.

Sitting in the crucible of violence that is Jamaica.

Mojito and murder.

Rape and reggae.

Haunted and hopeful.

Out of many conflicting experiences and emotions. My favorite rock. Jamaica . . . or as we call it “Yaad.”

Notes

- Dave Rodney, “Sintra Back on the Block with Her World-Famous Wet T-Shirt Poster,” Gleaner, August 11, 2015, https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/outlook/20150816/sintra-back-block-her-world-famous-wet-t-shirt-poster. ↩

- “Any Weather,” MP3 audio, track 1 on G6ixx Riddim, Shabdon Records, 2019.” ↩

- Nadine Wilson-Harris, “FORCED RIPE! Scores of Jamaica’s Children Are Being Pushed into Their First Sexual Encounters,” Gleaner, July 10, 2016, https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/lead-stories/20160710/forced-ripe-scores-jamaicas-children-are-being-pushed-their-first. ↩

- “Top 22 Dancehall Songs of 2022,” Gleaner, January 6, 2023, https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/entertainment/20230106/top-22-dancehall-songs-2022. ↩

- In 1669, Charles II, King of England, declared that a slave owner could not be charged with murder if a slave was killed in the course of punishment. A lesser known fact is this law was primarily to protect white women who would often punish enslaved children to death. “Act of the Commonwealth of Virginia,” Slavery and the Making of America, Thirteen, 2004, https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/living/docs1.html. ↩

- Denise Lee, “Jamaica is One of 5 Countries with 4 or More Beauty Queens Holding Miss World Titles,” https://jamaicans.com/jamaica-is-one-of-5-countries-with-4-or-more-beauty-queens-holding-miss-world-titles/ ↩