Resumen Reflexiono sobre mi experiencia con la discriminación silente hacia nuestras comunidades, abogando por la solidaridad entre ellas. Además, exploro la herencia del trauma colonial y cómo este se manifiesta en la desigualdad actual. En la lucha contra un sistema opresivo, señalo que la guerra no solo es contra fuerzas externas, sino también entre individuos que perpetúan la desigualdad. Destaco la existencia de privilegios que limitan el acceso a oportunidades básicas, convirtiendo derechos en exclusividades para algunes. El texto critica la estructura económica donde las grandes fortunas se mantienen protegidas, sin ceder a la equidad. La dificultad de escapar de un techo invisible que mantiene a ciertos grupos subyugados, creando una sociedad de pecera donde las oportunidades de crecimiento, limitadas. Abordo la idea de que una mejora materia materiall, no garantiza un avance espiritual ni la curación de las heridas ancestrales. Advierto sobre la pérdida de motivación para luchar colectivamente al integrarme en un sistema que ignora otras formas de resistencia. En el apartado sobre la colonia, exploro cómo la herida colonial sigue afectando la percepción colectiva, marcando una geografía racial que limita la autonomía. Desarrollo la idea de la ciencia moderna que categorizó a ciertos grupos como no humanos y cómo la lucha por ser reconocidos se convierte en una batalla contra la ignorancia y la explotación. Concluyo destacando los problemas sistémicos en el Caribe, la corrupción política y el discrimen, como reflejos de una realidad atrapada. La sombra del poder se manifiesta en la violencia policiaca y la exclusión a través de las leyes. En resumen, abordo la importancia de la solidaridad entre comunidades marginadas, cuestionando los privilegios y explorando las raíces del trauma colonial que persisten en la sociedad actual.

English translation by Khalila Chaar-Pérez

Habitamos el mundo de las comillas en donde las palabras no alcanzan a nombrar, a traducir, donde éstas pasan a ser provisorias por su inadecuación.

–Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso, “No existe sexo sin racialización”

¿Cómo no entender el despojo de tierras como una expresión de racismo si los despojados son los pueblos negros, indígenas y las comunidades campesinas? ¿Cómo no entender la composición humana de los ejércitos (legales e ilegales) como una expresión de racismo si los que combaten en primera fila son negros, indígenas y campesinos? ¿Cómo no entender las violencias que los monocultivos y la extracción de hidrocarburos han traído a los territorios negros, campesinos e indígenas como una expresión de racismo? ¿Cómo no entender esta guerra como un problema racista si las personas racializadas somos constantemente la carne de cañón?

–Jorge Ramos, líder social y activista por los derechos humanos en la Orinoquia, Comisión de la Verdad, 2020

El racismo polivalente

Son tantas y tan diversas las circunstancias donde los comportamientos discriminatorios encuentran terreno que parecería que no puede haber una sola definición que englobe el significado de racismo. Hablamos de un racismo que puede manifestarse más allá del discrimen de una a otra persona por el color de piel, siendo el color de la piel solo una de sus tantas acepciones. Es sabido que en su polivalencia el racismo puede presentarse a través de segregaciones sistémicas sutiles, Por ejemplo, Ebony Bailey explica que “cuando se desarrollaba los primeros rollos analógicos de color, la piel clara era la línea de base. A mediados del siglo XX, las tarjetas “Shirley” de Kodak, imágenes de mujeres blancas, eran utilizadas para calibrar luces, sombras y tonos de piel. Se utilizaban estas tarjetas alrededor del mundo y resultaba en que los tonos más oscuros quedarán sobre o subexpuestos. Kodak empezó a arreglar ese problema cuando unas compañías de muebles y chocolates se quejaron de la mala exposición en las fotos de sus productos. No fue la desfiguración humana lo que les hizo ver su error, fue el chocolate”. (Bailey, 2020) Existen situaciones más violentas como la inequidad laboral y salarial, el maltrato, las exclusiones y la invisibilización, pudiendo llegar incluso a la persecución, la agresión física y el exterminio de una etnia. El racismo puede cercenar la vida de una persona hasta su aniquilación o, lo que es peor, conducir a que la persona racializada se sienta inferior. Logra su objetivo no sólo cuando alguien impone sus derechos sobre los demás, sino cuando el discurso racista se internaliza y asienta como verdad en el imaginario de los pueblos racializados.

El racismo es una doctrina que defiende que un grupo étnico se sienta superior a otro, justificando así su discrimininación, segregación y explotación. Sin embargo, tener una definición de diccionario no da cuenta del entramado de escenarios donde puede aflorar el racismo. Es común que algunas personas confundan o nieguen sus comportamientos racistas no sólo por no reconocerlos en sus acciones, sino también por no querer asumir procesos de desconstrucción donde se pongan a prueba sus privilegios.

El racismo institucional está imbricado con asuntos de clase, género, ideología, etnia ambiente, que son algunas de las bases ideales para el despliegue camuflado de estas conductas discriminatorias por parte del Estado y el tejido social. Lo versátil de este término radica en que en cada una de las acepciones que acuerpa el racismo cambia en su modo de manifestarse y ser percibida.

Por ejemplo, está el racismo ambiental, que se hace visible mayormente en comunidades donde residen personas negras, indígenas, empobrecidas, donde no existe regulación para el asentamiento de fábricas y vertederos que contaminan el ambiente, que así afectan la salud y la calidad de vida de la comunidad, o en un barrio donde no recogen frecuentemente la basura, se instaura el mal olor y la podredumbre como parte de la estampa, y les más jóvenes del pueblo crecen consumiendo un ambiente inhóspito y descuidado. Eso se instaura en el subconsciente como ”lo normal”, perfilando ópticas sobre sí mismes: “Vivimos entre basura, somos la basura”. Antes que el Estado tenga la transparencia de reconocer que sostiene un modo de operar racista. Según Jorge Ramos, “el racismo atraviesa y determina el funcionamiento de la sociedad y del Estado. Tiene alcances estructurales. Opera de diferentes formas que a veces pasan desapercibidas o que no se entienden como una manifestación de racismo”. (Ramos, 2020) El Estado lo justificará como un problema económico-presupuestario y jamás como una decisión política. El Estado evade su responsabilidad de dirigir los recursos que velan por las condiciones de higiene y protección ambiental de todas las comunidades en su territorio. El Estado atiende de facto las zonas donde reside la clase alta. Asimismo, ubica los vertederos públicos cerca de las comunidades empobrecidas. Generando un sinnúmero de consecuencias, que lejos de ser un asunto económico es una conducta racista que se repite globalmente, convirtiendo el acceso a vivir en un espacio limpio y sin contaminación en un privilegio o asunto de clase y no en un derecho

Fuimos y somos migrantes

Nuestros tránsitos dan cuenta de una historia de migración forzada, de explotación, saqueos e invisibilización. Las realidades espaciales que vivieron esos cuerpos aún hoy nos acompañan. Cuando se mira la historia como un cúmulo que espiritualmente tizna, ya poco importa si une fue testigue ocular o no de los hechos. Conocer la historia nos fomenta un entendimiento macro. Somos hijes de la colonia y el cruce entre indígenas y migrantes esclavizades. Somos.

Ahora también somos locales desplazades de este Caribe cotizado por las agendas neoliberales que responden al capital. Como dice Bad Bunny, “Ahora todos quieren ser latinos.” (El apagón/Aquí vive gente, 2022)

Mi voz se enuncia desde un Caribe diaspórico y fragmentado. Nací en la República Dominicana, migré junto a mi familia de manera clandestina y crecí en el Puerto Rico de los noventa. Fui criada por dominicanas y cubanes migrantes. Crecer en la diáspora trae consigo la dicotomía de que lo que entendemos por hogar se ubica en el lugar de desarrollo y no en el de nacimiento. Mientras el racismo internalizado y la xenofobia que existe hacia les dominicanes en Puerto Rico no dejo de recordarme que no soy de acá. Mis paisanes cuestionaron mi dominicanidad por el acento o la jerga boricua que abracé mientras crecía.

Algunas generaciones diaspóricas ubicamos nuestra procedencia en un ”no lugar”. Aprendí a temprana edad a abrazar al otre y armar frentes comunes de resistencia. No hubo opción. Convivir con las minorías es una escuela de supervivencia. Vi de cerca el hambre, gente viviendo en la calle, racializades, empobrecides, migrantes indocumentades y comunidades lgbttqia+ marginadas. Crecer siendo parte de una estrata con ningún o contados privilegios te esculpe el pensamiento. Se decía en el barrio donde crecí que ”la necesidad tiene cara de hereje”. Ante tanto atropello y segregación externa no nos quedó de otra que desarrollar, a falta de todo, una conciencia antirracista en el hogar. No puedo decir que esto fue la norma del barrio, pero sí que tuve la suerte de que me enseñaron a no mirarme(nos) con el desprecio que aún hoy nos profesa la sociedad.

Las luchas adyacentes

Me siento más cerca de la lucha antirracista que de cualquier otra en este momento de mi vida. La intuición me dice que, venciendo esta batalla, mucho de lo que hoy nombramos como violencia no tardará en caer cuando se erradique el racismo.

Parece que es urgente que sigamos acentuando las semejanzas y similitudes de nuestras condiciones humanas y vayamos dejando atrás pensamientos nacionalistas e individualistas excluyentes. Reconozco que ya no encuentro representación en las voces radicales de los independentistas del país donde crecí. Esos discursos de izquierda que antes me despertaban el patriotismo diferido y que me erizaban la piel se disiparon. Sigo en desacuerdo con las prácticas coloniales que circundan la realidad que se vive en esta isla; conozco la sombra del estado benefactor que oprime, desplaza y explota nuestras tierras. Continúo apostando por la autonomía de nuestros pueblos. Sin embargo noté que ese discurso nacionalista que por tantos años defendí, no hizo un lugar para mí, ni les míes. Dejó fuera de su retórica y excluyó sin miramientos a las comunidades lgbttqia+, a les migrantes residentes, a la gente empobrecida. No hubo cabida para pensar en nuestras diversidades y entendernos como un mar de islas. Desconfíe de su capacidad para ver y atender un país diverso y me alié a otros tipos de saberes y activismos. Aquí en Puerto Rico se discrimina a les dominicanes, en la República Dominicana a les haitianes, en Costa Rica a les nicaragüenses, en Argentina a les bolivianes y así sucesivamente vamos por el mundo odiando al pobre más cercano. No hablo solo del Caribe, pero desde aquí me asiento y miro el mundo. Veo lejos una victoria contra este gran monstruo de odio que generó la blanquitud. Habría que mirar dos veces a nuestres vecines, abrazar sus luchas y hacer frentes comunes. Tendríamos que hermanarnos.

A prueba de balas

Puede que no tengamos nunca una imagen vívida del secuestro que vivieron nuestres ancestres racializades, pero bajo nuestra piel espiritual está el rastro. El trauma se hereda. Resabios tan profundos en la historia que marcaron un modo de ver y vernos en el mundo. Nacemos con la estampa de la percepción de un otre blanco que se presenta superior y que nos sugestiona. Dentro de esta sociedad donde no nos son accesibles a todes las mismas oportunidades, los derechos se convierten en privilegios para algunes: acceso a una vida y vivienda digna, un buen sistema de salud y educación, el salvaguardar que luego de pasar por procesos formativos podamos tener acceso a trabajos bien remunerados, se tenga o no aquel contacto que suele abrir los caminos. Se vuelve privilegio el derecho a ser integrades y respetades en una sociedad sin que importe el color de piel, el género, la preferencia sexual, la procedencia o los rasgos que exhibe nuestro cuerpo. Sobrevivir en estos ecosistemas regidos por el discrimen se ha convertido en un deporte de alto rendimiento. Vivimos en un pasado presente que aún late y reverbera con visible capacidad de repetirse para mantenernos al margen.

Es sabido que estamos en guerra unes contra otres, que hay miles que no dan cuenta de una estrata grande de existencias y que incluso están preparades para asentarse encima de ellas, explotando toda esa fuerza y vida hasta que vivamos mal y nos apaguemos sin revelarnos. Nuestras políticas se rigen a través de intereses etnocéntricos. Una rebelión significa la desestabilización de riquezas que están diseñadas para ser intocables, a prueba de balas. Hay familias con caudales económicos tan grandes que no van a poner en juego jamás el bienestar de su estirpe y descendencia. No hay ideas ni empatías que logren hacer que ese caudal se divida y promueva la equidad entre todes. La conciencia de la desigualdad encuentra su límite cuando toca el privilegio. Es la norma que conozco, aunque subterráneamente hoy pueda dar cuenta que están emergiendo otras, vengo aquí a hablar de lo que he visto. Ojalá que podamos seguir desaprendiendo como especie.

Es fácil llegar a olvidar que hay un techo invisible que busca mantenernos subyugades, bajo la raya de la desigualdad, vigilándonos entre nosotres, para que no queramos ni podamos ser más.

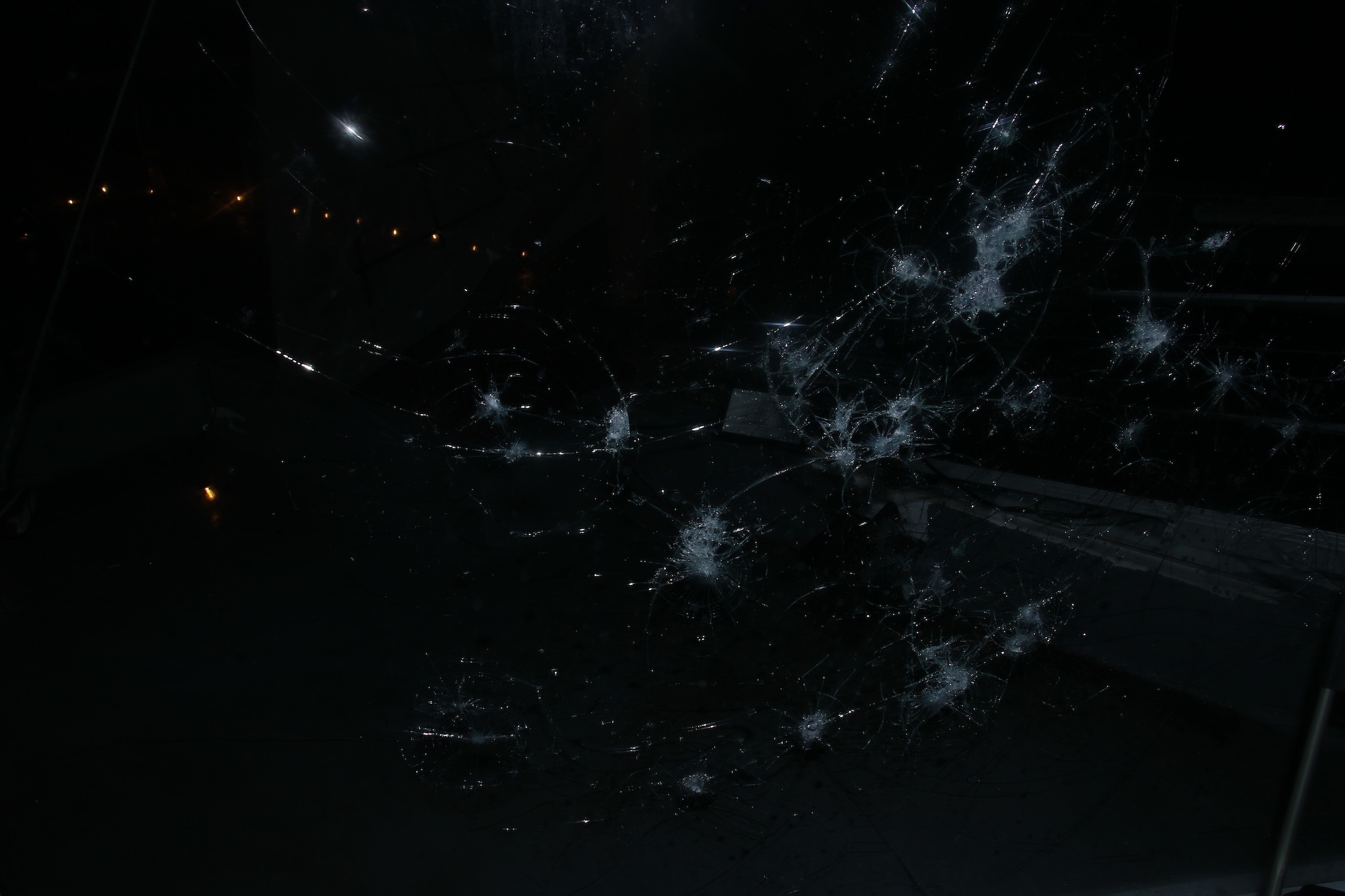

Es como un techo de cristal a prueba de ganas y balas, donde no se nos permite salir por ser quienes somos. Sin acceso a esos espacios de desarrollo donde podríamos aportar de muchas maneras nuestra sabiduría ancestral. Vivimos en una pecera. Nos hacen creer que tenemos igualdad de condiciones, pero no. Hay un andamiaje sólido y bien pensado que hace que nosotres vivamos circunscrites a unas realidades raciales que no nos permiten alzar vuelo. Si algune de nosotres logra salir de abajo y atravesar las grietas que tiene el sistema, le toca no inmolarse, inevitablemente blanqueade por la sed del capital y el deseo de querer agenciar una mejor calidad de vida y desde ahí jugar las cartas. Como explican Hilda Beatriz Quintero Corrales y Alexander Murillo Moreno sobre el caso de Colombia, “[Las] ideas racistas son promovidas desde narrativas públicas lideradas por referentes y políticos de la élite nacional cuyos juicios dan mayor sustento a la segregación. Los estereotipos han modificado costumbres y creencias de los segregados alterando su idiosincrasia; algunos cansados del asedio eligen parejas blancas para que sus descendientes tengan piel más clara, alejándolos de la segregación y facilitando el acceso a mayores oportunidades, aunque en el proceso tienden a perder su identidad”. (Quintero, Murillo, 2021)

Está claro que ese logro no necesariamente garantiza un avance espiritual o la restauración de la herida ancestral, sino al contrario, sólo evidencia que somos capaces de descodificar el sistema de odio y jugar el juego, aceptando la desigualdad como fuerza inevitable, mientras cada cual se agencia un bienestar individual que ignora por falta de medios otras vías de acción. Terminamos sumándonos a las fuerzas de la “matrix”, a veces perdiendo las ganas de luchar en el camino y callando a falta de verbos colectivos. Quiero terminar este pensamiento con un oximorón más optimista, porque aunque considero cierta la data que acabo de compartir, el cimarronaje que traigo encima no me deja aceptarme en amargura y resignación. Soy hija de mis tiempos, vine a gastarme la vida erradicando todas las desigualdades que pueda de este sistema. No está todo perdido.

La colonia

La colonia es un trauma, una herida matriz, un lente desde donde vemos el mundo, incluso sin querer. Esa cosmovisión se empieza a desconstruir en la medida en que nos vamos acercando a la historia negada, la que nos nombra como personas afrodescendientes, entre muchas virtudes, espiritualmente poderosas.

Sucede que vivir con el pensamiento colonial asentado en el inconsciente nos hace transitar el presente desde un lugar físico y espiritualmente inferior a ese otre. La ciencia moderna nos categorizó como no humanos, mientras el sistema político colonial puso nuestros derechos en la periferia de su agenda. Hubo que abrir camino a pico y pala. No existíamos según ellos. Hubo derramamiento de sangre para llegar a esa agenda y escribir en ella nuestros nombres. Cuando aparecimos en la historia se nos nombró para succionar de nuestros cuerpos su energía vital. Nos desarrollamos parasitades por gusanos blancos que se reproducen en serie y, sin conciencia de ello, se nutren de nuestra gesta. Amparades en la ignorancia, desde el supuesto no saber, nos chupan la sangre. Ver pieza audiovisual Comen de mí por Helen Ceballos (2023).

Nos recuerdo que el pensamiento blanco neoliberal no vive únicamente en cuerpos fenotípicamente blancos. Habló de la injerencia que tienen algunos sobre asuntos por los cuales no se ven afectados. Nos invito a vivir cada vez más lejos de la política identitaria blanca que nos pone a competir entre nosotres según el porciento de melatonina que haya en la piel. Que reduce nuestra experiencia a ver si soy o no visiblemente negro, tratemos en la medida de lo posible no pecar de miope y recordar que el sistema blanco colonial no conoce el colorismo. Va tras cuerpos racializados, pobres migrantes, latinos, indigenas, blancos, mestizos, o negros, nos racializan.

Vivimos un presente con un pasado latente que se repite como si la esclavitud y la segregación nunca hubiesen desaparecido. Se crearon leyes antidiscriminatorias que costaron vidas, pero no desapareció el racismo. Nos hacen creer que tenemos las mismas posibilidades pero que no trabajamos lo suficiente, creando unas olimpiadas de sacrificios entre nosotres (Baca, 2013). Parece que seguimos frente a la imagen de la realidad sin poder ver los píxeles que la componen.

Podemos nombrar instituciones y sistemas que antes de la abolición tenían un rol y ahora tienen otro similar en su perpetuidad. El feudalismo puso a producir la tierra con mano de obra de personas esclavizadas; hoy miles de personas siguen siendo explotadas en fábricas, plantaciones, minas y espacios donde ponen en riesgo su vida y salud, por encontrarse en situaciones desventajosas a causa de estas prácticas de explotación.

Las estadísticas dicen que las personas negras son más fácilmente procesadas y criminalizadas y reciben sentencias más severas que cualquier otro grupo. Angela Davis llamó a las cárceles el sistema esclavista moderno, en su perpetuación en su libro Are Prisons Obsolete? (Davis 2003, 37) . Hace sentido histórico que el trabajo que desempeña hoy la policía, surge del rol que desempeñaban quienes vigilaban a las personas esclavizadas para que no huyeran de las plantaciones donde eran explotades. Perseguidores de cimarrones ayer y hoy: Es un oficio con orígenes racistas. ¿Por qué todavía se perpetúa en el cuerpo policial esa tendencia de apresar a las personas negras?

Navegamos una especie de burbuja histórica donde aseguran que formamos parte de la sociedad en igualdad de condiciones. Incluso la fragilidad blanca nos tilda de ser racistas a la inversa, de que estamos obsesionades con la idea persecutoria de que estamos siendo marginades. Nos tildan de paranoiques; sin embargo nadie comprende cómo se traduce a la piel vivir la exclusión. Como aclara Jorge Ramos, “ Los discursos que imponen la superioridad de unas personas, de unas familias y de unas clases sobre otras son mucho más que palabras. Esos discursos se traducen en muertos, en masacres, en desplazamientos forzados, en hambre, en despojos. El racismo – como ideología, como sistema de ideas, como discurso- es el motor de esta guerra en la que los exterminados, los humillados, los heridos, los reclutados, los despojados y los abandonados son, en su mayoría, personas racializadas, negras, campesinas, indígenas, pobres: los que en la pirámide racista ocupan el último lugar” . (Ramos, 2020).

Las personas empobrecidas trabajan duro hasta morir, para sobrevivir bajo la sombrilla del estado racista que socava el desarrollo individual y colectivo desde antes de nacer.

Resistencias ancestrales

Es importante poner el oído en la tierra y entender las intersecciones que cortan las líneas de lo binario. Nuestro propósito es dirigir las fuerzas hasta conseguir que la política pública en el planeta sea antirracista e inclusiva. No basta con no ser racista; hay que ser antirracista, le escuché decir a Mayra Santos Febres alguna vez.

Apostamos a la revolución del placer y la libertad. Reconociendo lo efímero de nuestras vidas, lo fugaz que es el paso por la tierra, apostamos a vivir el ahora, conscientes que no habrá libertad política sin libertad sexual. Nos toca defender nuestras identidades y generar los espacios seguros que el sistema dinamita: construir el país donde queremos vivir.

Mi generación y las más recientes, honrando la ancestralidad, celebran la diversidad como un acto de resistencia. “Vamos a ser felices solo por joder” me dijo una vez mi madre. Hablemos de libertad de género, de personas intersexuales, transgénero y personas no binarias. Hablemos de siembra, de cuidar la tierra revolucionando la manera de vincularnos, de afectarnos para bien, de construir cosmovisiones de amor en resistencia a la pulsión de acostumbrarnos a normalizarlo. No podemos normalizar el racismo. Nosotras que lo conocemos no podemos normalizarlo. Veamos el racismo y las políticas del odio como algo finito y lo serán. De querencias a largo plazo, hablemos de un contraataque en colores, de sacar a un gobernador corrupto, perreando. De hacer valer nuestros derechos sin hacerle oda a la cuadrícula de cómo deben verse las personas respetables hoy, rompiendo el sello de la apariencia y trayendo temas sobre prejuicios y derechos al centro.

La labor del arte

Convengamos que el rol de les artistas con sus obras es alquímico. Supone bajar a tierra ideas que inviten a imaginar otra realidad posible. Partiendo de un tiempo cíclico le artista habla desde un lenguaje creativo que traduce lo literal a lo figurado a través de metáforas.

Nos pienso como el riñón del tejido social, ese órgano que va filtrando, en el mejor de los casos con pensamientos críticos, la historia diaria. Filtramos sucesos que el organismo ingiere por decisión propia o por falta de ella. La labor está en encontrar cómo esa traducción tiene llegada e interpela a otres, convocando maneras distintas de pensar.

A muchos tipos de expresiones artísticas no les interesa hablar sobre las polémicas del mundo, incluso se asientan en discursos que oscilan únicamente alrededor de ideas resueltas. Es decisión de cada artista ser perfume, filtro o deshumidificador en su oficio. Hay artistas que prefieren que su arte abone a la reverberación de lo bello, ser perfume. Hay otres que se comprometen con temáticas sociales que tienen que ver con políticas de cambio, artistas que filtramos a veces yendo a esos lugares que ”no huelen bien”, siendo quien inhala y exhala el hedor, y comparte su obra, traducida en metáforas. Este oficio puede ser un laburo denso de donde es difícil salir incólume La violencia de género, las desigualdades, la trata, el racismo, la xenofobia, y la sangre en el mar y en las fronteras son realidades pesadas, y hablar desde ahí ha sido un aprendizaje profundo.

Otres prefieren neutralizar ambas posturas y deciden acompañar la historia. Artistas que optan por ser periódicos de lo que pasa. Hay quienes persiguen los avances de la tecnología, y de la mano con la vanguardia crean piezas que parecen ser traídas de otras temporalidades, todas prácticas imprescindibles.

La sociedad está poblada de temas y asuntos que atender. Desde el calentamiento global hasta la muerte de los pandas. Les artistas somos de alguna manera les intérpretes causales para abrir nuevas conversaciones. Hacemos falta, aunque el mercado y el capital nos quieran presentar como prescindibles, es precisamente nuestro poder lo que espanta al sistema de control. No subestimo la fuerza y alcance que puede tener el arte hacia les seres vives, e intuyo que sanar esta herida que ha dejado el racismo en la historia de la humanidad es un trabajo espiritual, casi chamánico, y es oficio de las gentes sensibles bajar a tierra gestas que apoyen esta urgente reparación.

Cultural Constructions of Race and Crystal

We inhabit the world of commas, where words cannot be named, translated, where words are provisional due to their inadequacy.

–Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso, “There is no sex without racialization.

How can we not understand the displacement of land as an expression of racism if the people displaced are black, Indigenous, and farmers? How can we not understand human composition of (legal and illegal) armies as an expression of racism if those who fight in the front lines are people who are black, Indigenous and farmers? How could we not understand the violence that single-crop farming, and hydrocarbon extraction has brought to black, Indigenous, and farmer communities as another expression of racism? How can we not understand this war as a racist problem if racialized people are constantly the cannon fodder?

–Jorge Ramos, social leader and human rights activist in the Orinoquia, Truth Commission, 2020

I. Polivalent Racism

There are so many diverse circumstances where discriminatory behaviors find ground that it would seem that there cannot be a single definition that encompasses the meaning of racism. We are talking about a racism that can manifest beyond discrimination beyond the color of our skin, with skin color being one of its many meanings. In its versatility, racism can present itself through subtle systemic segregations. For example, Ebony Bailey explains, “When the first analog color rolls were developed by Kodak in the mid-twentieth century, images of white women were used to calibrate lights, shadows, and skin tones. These cards were used worldwide, resulting in darker tones being over or underexposed. Kodak began to fix that problem when some furniture and chocolate companies complained about poor exposure in their product photos. It wasn’t human disfigurement that made them see their mistake, it was chocolate.” 1 There are more violent issues, such as inequality in salary, mistreatment, exclusions, invisibilization, even up to persecution, physical aggression, and the extermination of an ethnic group. Racism can diminish the life of a person to the extent of annihilation, or worse, lead the racialized person into a position of feeling inferior. That is where racism wins: it achieves its objective, not just when one person imposes their rights over those of others, but when racist discourse is internalized and established as truth in the imagination of racialized peoples.

Racism is a doctrine that enables one ethnic group to feel superior to another, justifying its discrimination, segregation, and exploitation. However, having a dictionary definition doesn’t account for the framework of scenarios where racism can emerge. It is common for some people to confuse or deny their racist behaviors, not only because they don’t recognize it in their actions but also because they are not willing to undertake the process of deconstruction where their privileges are put to the test.

Institutionalized racism, intertwined with other issues of class, gender, ideology, ethnicity, environmental issues, just to name a few, are some of the ideal bases for the camouflaged deployment of these discriminatory behaviors by the state and the social fabric. The versatility of this term lies in the fact that in all of its meanings that racism embodies, it is a way of manifesting itself and being perceived changes.

For example, environmental racism is visible mainly in communities where Black, Indigenous, and impoverished people reside, where regulation for setting factories up and landfills that contaminate the environment are non-existent, even if they affect the health and quality of life of the community. In neighborhoods where garbage is not collected frequently, bad smells and rot are accepted as part of the picture, and younger people grow up inhabiting and consuming an inhospitable and neglected environment. This is established in their subconscious as normal, forming perspectives about themselves. “We live among garbage; we are garbage.” Before the state has the transparency to recognize that it sustains a racist way of operating, it will first justify and excuse its actions as an economic-budgetary problem, never as a political decision. According to Jorge Ramos, “Racism runs through and determines the functioning of society and the state. It has a structural scope. It operates in different ways that sometimes go unnoticed or are not understood as a manifestation of racism”. 2 The state evades its responsibility of directing resources that look out for the communities’ conditions of hygiene and environmental protection in their territory. In actuality, the state will tend to zones where upper-class people reside. The state assigns public landfills closest to impoverished communities. Generating endless consequences. Far from being an economic issue, this is racist conduct that repeats itself at a global scale, where access to living in a clean space without contamination is converted into matters of privilege and class and not a human right.

Il. We were and are migrants.

Our transient movements reveal our history of forced migration, exploitation, looting, and, in the end, an invisibilization of migration. The spatial realities that these bodies experienced still accompany us today. When we view history as an accumulation that is spiritually corrupted, it matters little if one was an eyewitness or not of these causes. Knowing history encourages a broader understanding. We are children of the colony and the crossing between enslaved Indigenous people and migrants.

Now, we are also displaced locals of this Caribbean, sought after by the neoliberal agendas that respond to capitalism. As Bad Bunny says, “Now everyone wants to be Latino.” 3

My voice is drawn from a diasporic and fragmented Caribbean. I was born in the Dominican Republic and migrated clandestinely with my family. I grew up in Puerto Rico in the nineties. I was raised by Dominican and Cuban migrants. Growing up in the diaspora brings with it a dichotomy that what we understand as home is located in a place of development and not in a place of birth. While the internalized racism and xenophobia that exists towards Dominicans in Puerto Rico was a constant reminder that I am not from here, fellow countrymen denied my Dominicanness because of my accent or because of the Boricua jargon that I embraced while growing up. For whatever reason, they denied it.

In many diasporic generations, we locate our origin from a non-place. From a very early age, I learned to hold and embrace the other and build a common front for resistance. There was no other option. Coexisting with other minorities in a school of survival, I saw from up close hunger, people living on the streets, radicalized, impoverished, undocumented migrants, and marginalized LGBTTQIA+ community. Growing up in a social stratum with no or few none privileges shapes one’s way of thinking. In the neighborhood where I grew up, it was said that “necessity has the face of a heretic.” I will add that amongst so much external abuse and segregation, we had no option but to uplift ourselves. In the absence of everything, we had an antiracist conscience at home.

I can’t say that this was the norm for everyone in my neighborhood, but I was lucky that I was taught not to look at myself and ourselves with the disdain that society still thrusts upon us today.

III. Adjacent struggles

At this moment in my life, I feel closer to the fight against racism than anything else. My intuition tells me that to win this battle, what we name today as violence won’t take long to disappear when racism is eradicated.

It seems that it is urgent to keep accentuating the likeness and similarities of our human conditions and leave behind nationalistic and individualistic discriminatory thinking. I recognize that I no longer find representation in those radical voices from the independent parties in the country where I grew up. Those leftist speeches that used to awaken my deferred patriotism and give me goosebumps, dissipated for me. I still am against colonial practices that surround the reality that exists on this island. I know very well of the shadow casted by the welfare state that oppresses, displaces, and exploits our lands. I continue to support the autonomy of our pueblos; nevertheless, I realized that the nationalist discourse that I defended for so long didn’t hold a space for me or my people. This discourse excluded any consideration for people in the LGBTTQIA+ community, resident migrants, and people who are impoverished. There was no room to include our diversities and understand us as a sea of many islands. I distrusted their ability to see and attend to a diverse country and allied myself with other politics and activism. Here in Puerto Rico, Dominicans are discriminated against; in the DR, it is the Haitians who are discriminated against; in Costa Rica, the Nicaraguan people; and in Argentina, it is Bolivians, and so on. We go around the world successively hating the nearest poorest person. We who want a different world would have to join forces. I think victory against this great monster of hate that whiteness generated is far away. We must look at our neighbors twice, embrace their struggles, and build a common front.

IV. Bulletproof

Perhaps we’ll never have a vivid image of the violence that our racialized ancestors lived through, but the traces of it remain within us spiritually, beneath our skin. Trauma is inherited. Remnants so deep in history that they marked the way we see ourselves and the world. We are born with the perception of a white other that appears superior and that influences us. Within a society where the same opportunities are not accessible for everyone, human rights become privileges only available to some: access to a dignified life and home; a good health system and education; the security that after formative years, we can have fair paying jobs, whether or not you have the connections that tend to open these opportunities. The right to be integrated and respected in a society, regardless of skin color, gender, sexual preference, origin, or the features of our body, becomes a privilege. Surviving in these ecosystems governed by discrimination has become a high-performance sport. We live in a past that still beats and reverberates with a visible capacity to repeat itself to keep us marginalized.

It is common knowledge that we are at war with each other, yet there are thousands who do not take into account the existence of large social groups. They are even prepared to position themselves above them, exploiting all that force and life until we live poorly and shut ourselves down without showing ourselves. Ethnocentric interests govern our politics. A rebellion would mean a destabilizing of riches that are designed to be untouchable and bulletproof. There are families with such great economic wealth that they would never put the well-being of their lineage and descendants at risk. There are no ideas or empathies that could reach this wealth to divide and promote equity to all. This is the norm I know. I hope before I leave here, I can find others.

It is easy to forget that there is an invisible ceiling that seeks to keep us subjugated under the line of inequality, policing each other so we don’t desire or be able to be more.

It’s like a bullet-proof glass ceiling, where we cannot leave because of who we are, without access to spaces of social development, where we could contribute our ancestral wisdom in many ways. We live in a fish tank. They want to make us believe we have equal conditions but we don’t. There is a very well-thought-out framework that confines us to living a racialized reality that doesn’t permit us to fly higher. If any of us manage to make it through the cracks in the system, rise from below, we must not destroy ourselves, inevitably whitewashed by capitalism and the desire to obtain a better quality of life, and from there let the chips fall where they may. As Hilda Beatriz Quintero Corrales and Alexander Murillo Moreno explain in the case of Colombia, “Racist ideas are promoted from public narratives led by leaders and politicians of the national elite whose judgments give greater support to segregation. Stereotypes have modified the customs and beliefs of those segregated, altering their idiosyncrasy; Some, tired of the siege, choose white partners so that their descendants have lighter skin, keeping them away from segregation and facilitating access to greater opportunities, although in the process they tend to lose their identity”. [4 Hilda Beatriz Quintero Corrales and Alexander Murillo Moreno, “El racismo como ideología y su negación en nuestras sociedades,” tradd. Mariposa Divina. Revista Perspectivas de Ciencias Sociales 6, no. 11 (2021): 97, https://doi.org/10.35305/prcs.vi11.434.]

It’s clear that this achievement doesn’t necessarily guarantee a spiritual advantage or a restoration of ancestral wounds; on the contrary, this is just evidence that we are capable of playing the game and cracking the code of this system of hate, accepting inequality as an inevitable force, meanwhile each one of us negotiates on our individual wellbeing that ignores other avenues of action due to lack of means. We end up joining the forces of the “matrix”: Losing the will to fight in our journey and falling silent, no longer using collective verbs.

V. The colony

The colony is a trauma, a wounded womb, a lens from which we see the world, even unintentionally. This worldview begins to deconstruct as we get closer to the history that has been negated, a history which names us as Afro-descendants, spiritually powerful people.

Living with colonial thought found in the unconscious makes us move through the present with the idea that the past accompanies us, which makes us relate to each other from a place of inferiority that we assume, even if we don’t believe in it. Meanwhile the political colonial system places us on the outskirts of their agenda. Modern science categorized us as non-human. We had to clear the way with sweat and tears and blood to belong to this agenda and be able to write our names in it. We didn’t exist. When we appeared in history, we were appointed to have our vital energy drained from our bodies. We developed parasites from mass-producing white maggots and without consciousness of it, fed from our achievements. Protected by ignorance, from the assumption of not knowing, they suck our blood. See Helen Ceballos, “Comen de mi,” 2023.

We are talking about some privileged people meddling in issues they are not affected by. In other words, there is a suppressed past that repeats itself as if slavery and segregation had never stopped existing. Non-discriminatory laws were created that cost people’s lives, but racism did not disappear. They make us believe we are given the same opportunities but that we don’t work hard enough, creating between us, sacrificial olympics. 4 We find ourselves faced by the image of truth yet unable to see the pixels that make it up.

We can name institutions and systems that had a role before the abolition of slavery and now have a similar role in their perpetuity. Feudalism put the land to production with enslaved people’s labor; today, thousands of people keep being exploited in factories, fields, mines, and spaces where their lives and health are at risk.

Statistics show that black people are more criminalized and prosecuted and receive longer and harsher sentences than any other group. Angela Davis named prisons modern-day enslavement in their perpetuity in her book Are Prisons Obsolete? 5

It makes historical sense that the work carried out today by police comes from the vigilantes whose role was to keep enslaved people from running away from where they were being exploited. Persecuting cimarrones (runaway slaves) yesterday and today. A job with racist origins. Why is this tendency to arrest Black people still perpetuated in the police force?

We are navigating a kind of historical bubble where they (the powers that be) ensure we form part of society under the same conditions. Even white fragility has accused us of reverse racism and of being obsessed with the persecutory idea that we are being marginalized. They call us paranoid, yet no one understands how the lived experience of exclusion can possibly translate to the skin. As Jorge Ramos states “The discourses that impose the superiority of some people, some families and some classes over others are much more than words. This discourse translates into deaths, massacres, forced displacements, hunger, and dispossession. Racism—as an ideology, as a system of ideas, as discourse—is the driving force of this war in which those exterminated, the humiliated, the injured, the recruited, the dispossessed and the abandoned are, for the most part, racialized black people. Farmers, indigenous, poor: those who occupy the bottom place in the racist pyramid”. 6

People who are impoverished work hard until they die to survive under the umbrella of the racist state that undermines the individual and collective growth since before they were born.

I want to end these thoughts with an optimist oxymoron. Even though I consider the data I share accurate, the cimarronaje that I carry on me does not let me accept myself with bitterness and resignation. I am a daughter of my times. I came to spend my life fighting against the system’s inequalities. Not everything is lost.

VI. Ancestral Resistances

It is important to put your ear to the ground and understand the intersections that cut the lines of the binary. Our purpose is to direct the forces until we get public policy across the planet that is antiracist and inclusive. It is not enough to not be racist; we must be antiracist.

We are betting on a revolution of pleasure and freedom. Recognizing the ephemerality of our lives, how fleeting passing through this world is, we commit to living in the now, with an awareness that there will be no political freedom without sexual freedom. It is our turn to defend our identities and generate those safe spaces that the system destroys. Build the country we want to live in.

My generation and most recent ones honor ancestrality. We celebrate diversity as an act of resistance. My mother told me once, “We will be happy, just for fuck’s sake.”Let us talk about the liberty of gender, of people who are intersex, transgender, and non-binary. Let’s talk about sowing, of taking care of the earth in ways that can revolutionize the way we connect with each other, of changing each other for the better, of constructing worldviews of love just as strong and everlasting as those built before by racism and politics of hate. Let’s talk about long-term desires, about a counterattack of colors, about removing a corrupt governor by twerking. Let us have our rights valued without supporting the script telling us what respectable people are supposed to look like, breaking the prescription of appearances, and bringing themes of prejudice and human rights to the center.

VII. The role of art

We can agree that the role of artists with their work is one of alchemy. It entails bringing down-to-earth ideas that invite us to imagine other possible realities. Starting from a cyclical time, the artist speaks from a creative language that translates the literal to the figurative through metaphors.

I think of us as the kidney of the social fabric, an organ whose work is to filter—in the best cases, filtering with critical thought—daily history. We filter situations that the organism ingests by its own decision or for lack of it.

The job is to find how that translation reaches and challenges others, summoning different ways of thinking. Many types of artistic expressions aren’t interested in talking about the controversies of the world; some even settle on discourses that only oscillate around resolved ideas. Every artist has the choice to be a perfume, a filter, or a dehumidifier in their craft. There are artists that prefer to be perfume, that prefer their art to subscribe to the reverberation of beauty. Others commit to social themes that have to do with political change. Artists who are filters sometimes go to those places that don’t “smell good,” inhale and exhale the stench, and share their work, translated into metaphors. This profession can be arduous labor and getting out unscathed is challenging. Gender violence, inequalities, trafficking, racism, xenophobia, and blood at sea and on borders are heavy realities, and speaking from this place has been a profound learning experience for me.

Others prefer to neutralize both postures and decide to accompany the story. Artists that prefer and opt for being newspapers of what is happening. There are those that pursue advances in technology and alongside the avant garde create pieces that appear to come from different eras, all practices are indispensable.

Society is overwhelmed by and issues to attend to, from global warming to the killing of pandas. Artists are in some ways the casual interpreters that can open new conversations. We are needed, even if the market and capitalism want to make us seem disposable. Our power is precisely what scares the people in control. I do not underestimate the force and reach that art can give to living beings, and I sense that healing this wound that racism has put on the history of humanity is spiritual work. It is almost shamanic, and it is the job of artists, among other people to channel down to the earth these works that support this urgent need for repair.

- Ebony Bailey, “Racismo en la fotografía,” Pie de página, July 4, 2020, https://piedepagina.mx/racismo-en-la-fotografia. ↩

- Jorge Ramos, “El racismo es una ideología que contribuye a prolongar y a degradar la guerra,” tradd. Mariposa Divina, Comisión de la Verdad, July 31, 2020, https://web.comisiondelaverdad.co/actualidad/noticias/el-racismo-es-una-ideologia-que-contribuye-a-prolongar-y-a-degradar-la-guerra. ↩

- Bad Bunny, “El apagón / Aquí vive gente,” directed by Bianca Graulau, Rimas, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1TCX_Aqzoo4. ↩

- Susana Baca, vocalist, “María Landó,” by César Calvo y Chabuca Granda, YouTube, June 6, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c8xuRPIdDjc&list=RDc8xuRPIdDjc. ↩

- Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Open Media, 2003) 37. ↩

- Jorge Ramos, “El racismo es una ideología que contribuye a prolongar y a degradar la guerra,” tradd. Mriposa Divina, Comisión de la Verdad, July 31, 2020, https://web.comisiondelaverdad.co/actualidad/noticias/el-racismo-es-una-ideologia-que-contribuye-a-prolongar-y-a-degradar-la-guerra. ↩