For a roughly eight-year period beginning in 2005, around fifty thousand African refugees crossed into Israel.1 Most of them were fleeing war and violence in Eritrea, South Sudan, and Darfur, and their path to Israel involved an often perilous journey across the Sinai Peninsula where they dealt with hostile Egyptian authorities, harsh environmental conditions, and predatory bands of smugglers and human traffickers. Israel still refuses to classify these African asylum-seekers as refugees and instead sees them as “economic migrants” or even as “infiltrators” (mistanenim), a term that appears not only in right-wing hate speech but in standard Israeli legal discourse. They have been locked up by the thousands in the Holot Detention Center, an open air prison in the Negev Desert, and many have also been deported—sometimes back to the very countries from which they fled. Israel’s treatment of the refugees thus flies in the face of international law, specifically the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention—ironically, an agreement that Israeli delegates played a key role in passing in the wake of the Holocaust.2

These asylum-seekers are certainly not the only Black community in Israel to have fought racial discrimination. Here, one may be reminded of the Mizrahi Jews who formed their own Black Panther Party in the 1970s or the Ethiopian Jewish activists today who decry their treatment as second-class citizens. But, as a Black community that is not even Jewish, the situation of these asylum-seekers is particularly precarious. Their plight first caught my attention in 2012. That year, there was a dramatic rise in hate speech and racist violence against them. After one demonstration, a mob of anti-African protesters descended upon Hatikva, a South Tel Aviv neighborhood where many of the refugees live. Chanting “The People Want the Africans to Be Burned!,” they bombed a kindergarten and smashed the windows of several African-run shops.3 Around the same time, former Israel Defense Forces (IDF) spokesperson Miri Regev gave speeches calling the Africans a “cancer.” She later apologized for this comment—not to the asylum-seekers but to Jewish cancer survivors; she was sorry for comparing them to Black Africans.4 Similarly, Interior Minister Eli Yishai of the Shas party told a reporter that “this country belongs to us, to the white man.” He vowed to use “all the tools [necessary] to expel the foreigners, until not one infiltrator remains.”5 Here, it is worth noting that both of these politicians have their origins in North Africa. Regev’s father is a Moroccan Jew; Yishai’s family is Tunisian. As is so often the case, those whose claim to whiteness is the most tenuous—in this instance, Mizrahi Jews—turn out to be the racial pecking order’s most virulent enforcers.6

But Israel’s population of African refugees are not just passive victims. They have fought back, staging protests with their bodies and voices. In 2013, several hundred Africans incarcerated in Saharonim Prison went on a hunger strike to protest their unjust treatment.7 Others took to the streets, and in the same year some twenty-five thousand people marched in the largest such protest.8 In some instances, the refugees have created protest spectacles. At a 2018 demonstration in Tel Aviv, for instance, they painted their faces white to call attention to Israel’s supremacist racial hierarchy. On another occasion, they staged a mock slave auction. This was done as a response to the Israeli government’s deportation policy which effectively sought to bribe the refugees into leaving with a few thousand dollars in cash and a one-way plane ticket back to Africa.9 Those without ownership of the media thus attempted to take command of it, and their activism did not go unnoticed. As a result of both the amplification of racism against the migrants and the increase of coordinated resistance against it, some Israeli citizens took action. Since the early 2010s, the plight of the refugees has inspired a number of philanthropic initiatives and cultural productions, including journalistic exposés, novels, and documentary films.10 In this way, the African asylum-seekers became the subject of an Israeli philanthropic gaze: Black skins in front of white cameras.

In the last decade, there have been five Israeli documentaries produced about the African refugees: Sound of Torture (2013), directed by Keren Shayo; African Exodus (2014), directed by Brad Rothschild; Ethnocracy in the Promised Land: Israel’s African Refugees (2015), directed by Lia Tarachansky and Jesse Freeston; Hotline (2015), directed by Silvina Landsmann; and Between Fences (2016), directed by Avi Mograbi.11 All of these films champion the cause of the refugees, and their appearance on Israeli screens might therefore be welcomed as a humanitarian counterweight to the violent rhetoric and actions of Israel’s racist Right. However, while the discourse of liberal inclusion is certainly preferable to overt bigotry, it is not necessarily all that radical. Indeed, as Wendy Brown and Ghassan Hage have argued in the context of two other white settler-colonial states—the United States and Australia, respectively—multicultural tolerance can function not to overturn existing racial hierarchies but to extend their reach. In Brown’s words, “tolerance . . . manages the demands of marginal groups in ways that incorporate them without disturbing the hegemony of the norms that marginalize them.”12 Zionists, too, can play the game of multicultural colonialism, and their closet of white sheets can also contain a coat of many colors.13

In these documentaries, then, the belligerent language of anti-African hatred is replaced by the benevolent words of liberal tolerance, but this does not necessarily mean that whiteness itself is challenged. Indeed, while all five of these films are critical of Israeli government policies vis-à-vis the asylum-seekers, they couch their criticisms in very different terms. If some leave the racial hierarchies of Zionism intact, others attempt to shatter them—two dueling tendencies which I will explore in the films Hotline and Between Fences. Thus, while the racial dynamics of Israel are usually examined with respect to intra-Jewish tensions (i.e., Ashkenazi supremacy) or the Palestinian issue (i.e., settler-colonialism), in this essay, I want to consider Israeli whiteness with respect to the African refugees.14

Hotline follows the activities of a small Tel Aviv-based non-profit organization, the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants. The women who work there face numerous hurdles as they navigate Israel’s complicated and sometimes Kafkaesque bureaucracy in order to assist the refugees—in town hall meetings, in special sessions of the Knesset, and in the Israeli courts. Inspired by cinema vérité and specifically the work of Frederick Wiseman, Hotline’s director Silvina Landsmann sought to give viewers a fly-on-the-wall look at Israeli institutions—a style she also adopted in her earlier film Soldier/Citizen (2012).15

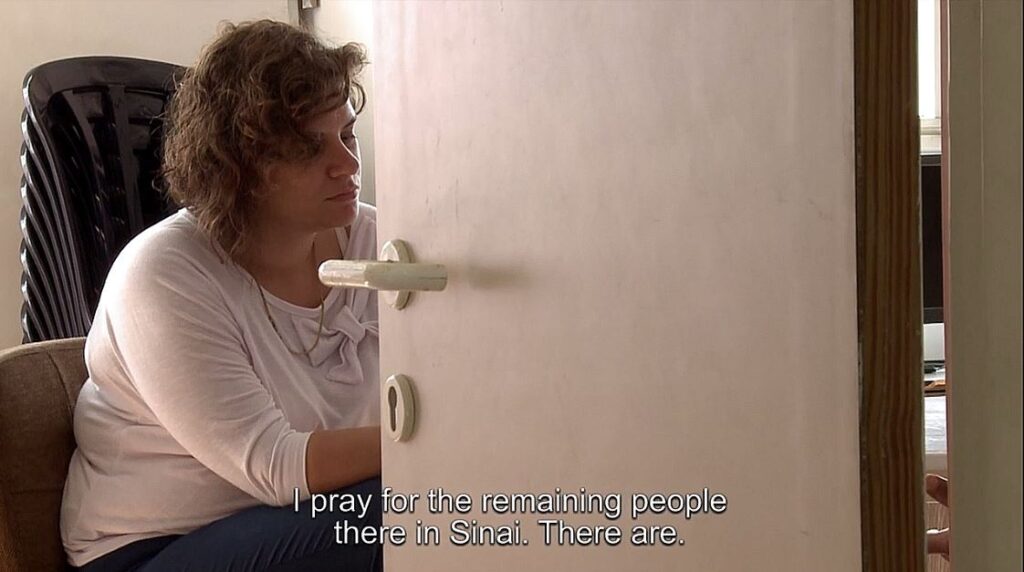

Hotline thus refrains from overt commentary. There are no talking heads, no charts or graphics, and no voice-over narration. Such an approach to documentary has sometimes been lauded for its ostensible neutrality. Indeed, at least one of Hotline’s reviewers praised the film for its “non-editorialising approach” and its “detached observational stance.”16 As is always the case, however, objectivity is not really so objective, and whether the director intended it or not, her authorial voice does emerge throughout the film.17 Towards the end of Hotline, for instance, there is a very revealing sequence. A worker from the organization sits across from a refugee and listens to him recount his harrowing journey across the Sinai. They are positioned behind a partially open door, and the film frames them so that while we can clearly see the face of the Israeli, the African remains completely obscured. All we can see of him is an occasional hand gesture through the crack in the door. One can only assume that he was hidden to protect his identity, but this very deliberate framing nevertheless demonstrates a troubling tendency. The film’s attention is always on white Israeli women. They are the heroes, not the asylum-seekers. Hotline is not a film about Black liberation; it is a film about the empowerment of white Israeli women.

To be clear, my critique here should not be construed as an attack on the Hotline agency itself. Rather, my critique has to do with the way this agency is framed, the way the film foregrounds Hotline’s staff members without recognizing how their positions are part of the same racial regime that oppresses African refugees. By emphasizing the Israelis’ agency over that of the Africans, Hotline suggests that salvation can come from within Israeli civil society without in any serious way transforming that very society.

In Hotline, there are two major groups of antagonists. The first is the audience that viciously confronts one of Hotline’s organizers in a South Tel Aviv auditorium. The crowd is mostly made up of Mizrahi women who accuse her of being a rich Ashkenazi, and one of them even curses the Hotline representative to her face: “I hope your girls get raped.” Simply put, in Hotline, the Mizrahim are monsters. In this way, the film gets caught up in that old blame game, displacing the symptoms of structural racism onto individual scapegoats. Israel’s foundational racial hierarchy—a European fantasy of phallic white supremacy—is thus projected onto the Mizrahi devils. Anti-African bigotry is ironically presented not as a problem endemic to Zionism but as a problem stemming from those Israelis who are not yet fully Israeli; the solution is not a dismantlement of whiteness but further assimilation into it.18

Hotline’s second group of antagonists is the condescending male politicians who smugly dismiss the Hotline representative at a special session of the Knesset. One of them even jokes about deporting her along with the African “infiltrators,” and his colleagues all laugh at his offensive comment. In Hotline, these two antagonistic groups—the angry Mizrahi women and the patronizing patriarchal politicians—end up serving the same function as the Africans; all of them are props that the film uses to bolster the heroism of white women. Thus, Hotline fashions itself as a social justice-minded feminist film, and it was treated as such on the international film festival circuit. If Hotline is feminist, however, is a very particular type of feminism—a feminism that glorifies the actions of white women without pausing to reflect on the privilege of their racial position.19 The Africans are treated sympathetically, but only in a way in which members of Israeli civil society emerge as the true heroes.

Between Fences is a very different kind of film. Taking place almost entirely at the Holot Detention Center, the film follows a group of African refugees as they work together with an Israeli filmmaker (the director himself, Avi Mograbi) and an Israeli theater director (Chen Alon) to perform scenes of “theater of the oppressed”-style drama.20 If other documentaries, including Hotline, treat the Africans primarily as victims, Between Fences takes a different approach, and in their interviews, conversations, and performances, the Africans exhibit fuller personalities and more creative spirits than in any of the other films. Indeed, of all of the Israeli documentaries about the asylum-seekers, Between Fences is the only one in which they are allowed to laugh.21 While the film certainly does not ignore or deny the tremendous injustice these refugees face, neither does it let that injustice completely dominate them. If social justice documentaries often try to prove the humanity of their oppressed subjects, Between Fences presumes their humanity from the outset.22 In a very Rancièrian way, then, Between Fences presupposes equality as a given.23

As a result, the Israelis presented in the film are not treated as particularly heroic. Their actions, including their participation in the performances and their apparent solidarity with the refugees, is not the point of the film. If anything, the film works not to glorify but to humble the Israelis—that is, to indict whiteness itself.

Unlike Hotline, Between Fences makes no claims to detached neutrality, and if Landsmann uses cinema vérité methods to disguise her own authorial presence, Mograbi does the opposite and puts himself directly in the film. Even though he is present, however, he is not the center of attention, and when he does appear, it is often in a very self-depricating way. At one point in the film, for instance, Mograbi tells the African performers that he will not be coming to their next meeting because he has to travel abroad. Mograbi does not try to hide his privilege. He merely states the facts of the situation without trying to camouflage or sugarcoat them. By including this uncomfortable moment in the film, Mograbi invites audiences to reflect on the injustice of the situation. As an Israeli man, he can freely travel abroad, while the main stars of the film, the Africans, are stuck in the desert. This contrast between Mograbi and the Africans—between the privileged and unprivileged, between the mobile and immobile, between white and Black—could not be any starker. Mograbi thus appears to be using himself to criticize the power and privilege of white Israelis.24

This tactic connects Between Fences to Mograbi’s larger filmography. Early on in the film, there is an awkwardly long sequence in which he speaks to an African refugee sitting behind a fence. It is an image that closely resembles shots in his other films. At the end of August: A Moment Before the Eruption (2002), for instance, Mograbi takes his camera north to Israel’s border with Lebanon. On the other side of the fence, a boy looks at Mograbi while Mograbi looks at him. They exchange a few words, the boy in Arabic, Mograbi in Hebrew. The boy then shouts some slogans about Hezbollah, throws a few rocks at Mograbi, and saunters away. Similarly, the first Palestinians to appear in Avenge But One of My Two Eyes (2005) are also stuck behind a fence. They are workers in the West Bank, people simply attempting to go to their jobs, but Israeli soldiers have arbitrarily closed the gate shut. The Palestinians find themselves waiting with no end in sight.

In all three of these examples, Mograbi lets the camera linger on the fence—a barrier separating the Israeli from the African, the Lebanese Arab, and the Palestinian. Significantly, it is a barrier which Mograbi himself does not cross. One does not get the impression that Mograbi is looking into a cage, like a tourist at a zoo. Rather, one gets the impression that Mograbi is himself in the cage, looking out at a bigger world around him. His Israeli passport may give him certain privileges and international mobility, but in terms of his identity, he is trapped. These sequences highlight the fences, borders, and manufactured divisions that Israel has constructed between the white, Western Jew and its various racialized Others. In this way, Mograbi is once again using himself to criticize his own position.25

To be sure, Mograbi is not denying his own identity as an Israeli Jew, and his approach therefore stands in contrast with others like Shlomo Sand whose critical views of Zionism have led him to renounce his own Jewishness.26 But neither does Mograbi make the mistake of so many other white activists who reject the centrality of their own identity so loudly that they ironically end up putting themselves at the center once again. If other films end up treating the African refugees as props in order to bolster existing elements of Israeli society, Mograbi’s self-deprecating approach shatters this possibility. As such, screenings of his films are increasingly rare in Israel. There is little wonder, then, that while Hotline received top prizes at prestigious Israeli film festivals, Between Fences was not picked up by any Israeli distributors. It was simply far too subversive, its message far too scandalous. Israelis do not seem to have a stomach for Mograbi’s documentaries, and in a recent interview, he even suggested that he makes his films for himself and for people abroad.27 In some way, he seems to be giving up on Israeli society and along with it, the power and privilege of its supremacist racial regimes.

In this paper, I have argued that the African refugees provide an important starting point for the examination of Zionism’s racial hierarchies. While some Israelis have openly opposed the presence of African asylum-seekers, others have taken a more inclusive approach. This latter group includes several filmmakers, and the documentaries that have been produced about the treatment of African refugees in Israel seek to humanize them, to criticize Israeli government policies against them, and to champion the philanthropic efforts of white Israelis. As we have seen in Hotline, however, such efforts easily slip into another kind of racism, and while the tone of these films sharply contrasts with that of Zionism’s more explicitly white supremacist defenders, they usually fail to criticize whiteness itself. In this way, whiteness is not dismantled; it is reinforced. Between Fences is the exception, and rather than glorifying the position of white Israelis, this film indicts it.

Notes

- Although I am using the term “Israel” for convenience, the territory currently administered by the Israeli government is, together with the West Bank and Gaza, part of Palestine. ↩

- Gilad Ben-Nun, Seeking Asylum in Israel: Refugees and the History of Migration Law (London: I.B. Tauris, 2017), 19–50. See also Mya Guarnieri Jaradat, The Unchosen: The Lives of Israel’s New Others (London: Pluto, 2017); and Sarah S. Willen, Fighting for Dignity: Migrant Lives at Israel’s Margins (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2019). ↩

- See Yotam Gidron, “World Refugee Week: A Community Deported, in Pictures,” +972 Magazine, June 22, 2012, https://www.972mag.com/world-refugee-week-a-community-deported-in-pictures/; and Max Blumenthal, Goliath: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel (New York: Nation, 2013), 344. ↩

- Quoted in Ali Abunimah, “Israeli Lawmaker Miri Regev: ‘Heaven Forbid’ We Compare Africans to Human Beings,” Electronic Intifada, May 31, 2012, https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/ali-abunimah/israeli-lawmaker-miri-regev-heaven-forbid-we-compare-africans-human-beings. ↩

- Quoted in Dana Weiler-Polak, “Israel Enacts Law Allowing Authorities to Detain Illegal Migrants for Up to 3 Years,” Ha’aretz, June 3, 2012, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-s-new-infiltrators-law-comes-into-effect-1.5167886. ↩

- On the Mizrahim, see Ella Shohat, “Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Jewish Victims,” Social Text 19–20 (1988): 1–35; and Yaron Shemer, Identity, Place, and Subversion in Contemporary Mizrahi Cinema in Israel (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2013). ↩

- Noam Dvir, “Saharonim Detainees Go on Hunger Strike,” Ynet, June 27, 2013, https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4398026,00.html. ↩

- Lee Yaron, “25,000 Protest in Tel Aviv Against Israel’s Asylum Seeker Deportation Plan,” Ha’aretz March 24, 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/25-000-protest-in-tel-aviv-against-deportation-of-asylum-seekers-1.5938048. ↩

- Abdi Latif Dahir, “African Migrants Are Painting Their Faces White to Stop Israel from Deporting Them,” Quartz Africa, February 26, 2018, https://qz.com/africa/1215813/photos-eritrea-and-sudan-migrants-paint-faces-white-to-protest-rwanda-deportation; “State Said Set to Tell High Court Migrant Deportation Deal to Uganda Still on,” Times of Israel, April 8, 2018, https://www.timesofisrael.com/state-to-tell-high-court-that-deportation-deal-with-uganda-still-on-report. ↩

- See the novel, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, Waking Lions, trans. Sondra Silverston (London: Pushkin, 2016). First published in Hebrew in 2014 by Kinneret Zmora-Bitan Dvir (Or Yehuda, Israel). Also of relevance here is the short film The Ambassador’s Wife (dir. Dina Zvi-Riklis, 2016), discussed in Rachel S. Harris, Warriors, Witches, Whores: Women in Israeli Cinema (Detroit: Wayne State University, 2017), 235–36. ↩

- Two of these documentaries are Israeli only insofar as their directors hold Israeli citizenship. African Exodus was directed by Brad Rothschild, a dual US-Israeli citizen who once worked as a speechwriter for the Israeli delegation to the UN, and Ethnocracy in the Promised Land was co-directed by Lia Tarachansky, an investigative journalist-turned-filmmaker who grew up on a West Bank settlement before breaking with Zionism and immigrating to Canada. The Israeliness of the other three films is more firmly established. Not only were they helmed by Israeli directors, but they were produced by Israeli companies and financed at least partially with Israeli funds. ↩

- Wendy Brown, Regulating Aversion: Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire (Princeton: Princeton University, 2006), 36. Likewise, for Hage, “White multiculturalism and White racism, each in their own way, work at containing the increasingly active role of non-White Australians in the process of governing Australia.” Ghassan Hage, White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society (1998; New York: Routledge, 2000), 19. Emphasis in original. See also Slavoj Žižek, “Multiculturalism, or, the Cultural Logic of Multinational Capitalism,” New Left Review 1, no. 225 (1997): 28–51. ↩

- For an example of Zionist multiculturalism, see Gil Hochberg, “Forget Pinkwashing, It’s Brownwashing Time: Self-Orientalizing on the US Campus,” Mondoweiss, November 28, 2017, https://mondoweiss.net/2017/11/pinkwashing-brownwashing-orientalizing. ↩

- Recent discussions of race in Israel include Ronit Lentin, Traces of Racial Exceptionalism: Racializing Israeli Settler Colonialism (London: Bloomsbury, 2018); and Yasmeen Abu-Laban and Abigail B. Bakan, Israel, Palestine and the Politics of Race (London: I.B. Tauris, 2019). See also David Theo Goldberg, “Racial Palestinianization,” in Thinking Palestine, ed. Ronit Lentin (New York: Zed, 2008), 25–45. ↩

- Eric Cortellessa, “‘Hotline’ Film is Hands-Off Yet Intense Look at Rights Group,” Times of Israel, July 27, 2015, https://www.timesofisrael.com/hotline-film-is-hands-off-yet-intense-look-at-rights-group. ↩

- Jonathan Romney, review of Hotline, Screen Daily, February 9, 2015, https://www.screendaily.com/hotline/5083023.article. ↩

- For an earlier critique of documentary cinema’s truth claims, see Brian Winston, “The Documentary Film as Scientific Inscription,” in Theorizing Documentary, ed. Michael Renov (New York: Routledge, 1993), 37–57. ↩

- For a discussion of the African asylum-seekers that takes into account the Ashkenazi-Mizrahi divide, see Nir Cohen and Talia Margalit, “‘There Are Really Two Cities Here’: Fragmented Urban Citizenship in Tel Aviv,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, no. 4 (2015): 666–86. ↩

- The racial blindspots of white feminism have been widely acknowledged. See, for instance, Ruth Frankenberg, White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1993). For critiques of Israeli feminism along these same lines, see Nahla Abdo, Women in Israel: Gender, Race, and Citizenship (London: Zed, 2011); and Smadar Lavie, “Mizrahi Feminism and the Question of Palestine,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 7, no. 2 (2011): 56–88. ↩

- Between Fences can be compared to similar movies from the region that involve performances by other oppressed communities: the Palestinian torture victims in Raed Andoni’s Ghost Hunting (2017), for instance, or the Lebanese prisoners and kafala workers in Zeina Daccache’s 12 Angry Lebanese (2009), Scheherazade’s Diary (2013), and Shebaik Lebaik (2016). The African actors eventually took their show on the road, and they gave a number of performances elsewhere in Israel. See Sonja Arsham Kuftinec, “Holot Legislative Theatre: Performing Refugees in Israel,” TDR/The Drama Review 63, no. 2 (2019): 166–72; and Ofer Perelman, “How a Sudanese Asylum Seeker Caught the Acting Bug in Holot,” Ha’aretz, March 17, 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-how-a-sudanese-asylum-seeker-caught-the-acting-bug-in-holot-1.5911079. ↩

- Although not discussed in detail here, the documentary Ethnocracy in the Promised Land also deserves credit for taking an explicitly critical position vis-à-vis Zionism. ↩

- Palestinian filmmaker Annemarie Jacir similarly criticizes this tendency on the part of some filmmakers to humanize Arabs. As she argues, “To make work that will essentially ‘humanize’ or ‘explain’ Arabs is so limiting and, in fact, insulting, and I think it kills the potential of what I consider art. People who still don’t get that Arabs are layered, complex ‘humans’ are simply not the audience I am interested in.” Annemarie Jacir, et. al., “‘I Wanted That Story to be Told’ (Interview),” Alif 31 (2011): 246. ↩

- In his writings, Jacques Rancière seeks to fundamentally redefine our notion of equality. For him, equality is not a policy decision or a piece of legislation, but a supposition to be made from the outset. This view has very important political implications. For Rancière, it is not that there would be no equality without a preceding struggle; rather, there would be no collective struggle against inequality without a preceding supposition of equality. That is, inequality is properly opposed only because equality is first presupposed. Rancière’s argument thus directs our attention towards the real, everyday existence of equality in the present, and his work can therefore be compared to the thinking of other scholars like bell hooks and Wendy Brown who similarly argue that emancipatory politics is subverted as long as it is based on wounds or brokenness. By treating the African asylum-seekers as equals from the outset, Between Fences performs this same act. The film does not seek to prove their equality; it just assumes it. See Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, trans. Julie Rose (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1999). First published in French in 1995 by Éditions Galilée (Paris). See also bell hooks, “Lorde: The Imagination of Justice,” in I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde, ed. Rudolph P. Byrd, Johnnetta Betsch Cole, and Beverly Guy-Sheftall (New York: Oxford University, 2009), 248; and Wendy Brown, “Wounded Attachments,” Political Theory 21, no. 3 (1993): 390–410. ↩

- Writing about Mograbi’s earlier films, Shai Ginsburg similarly claims that “the filmmaker often serves as a primary figure of identification, as the audience is drawn to admire his (or her) courage, honesty and integrity. Mograbi works hard to undercut this tendency.” Shai Ginsburg, “Studying Violence: The Films of Avi Mograbi,” Zeek, October 24, 2009, https://zeek.forward.com/articles/115717. ↩

- As a Tel Aviv-born Israeli, Mograbi refers to himself as “white” in the film, but it is important to note that he is Mizrahi. As Mograbi explains in his previous documentary Once I Entered a Garden (2012), his family’s origins are in Beirut and Damascus. ↩

- Although Sand claims to reject all forms of ethnic or racial essentialism, he nevertheless seems to advance a very essentialist understanding of Jewishness when he fails to see how it can be articulated in non-Zionist terms. See his book, How I Stopped Being a Jew, trans. David Fernbach (New York: Verso, 2014). First published in Hebrew in 2014 by Kinneret Zmora-Bitan Dvir (Or Yehuda, Israel). ↩

- Mograbi: “My films…interest me and people abroad. They don’t interest the audience in Israel that much. I continue making films because I can’t stand idly by…to give it up, for me, is to give up on life.” Quoted in Dror Dayan, “The Manifestations of Political Power Structures in Documentary Film,” (PhD diss., Bournemouth University, 2018), 111. ↩