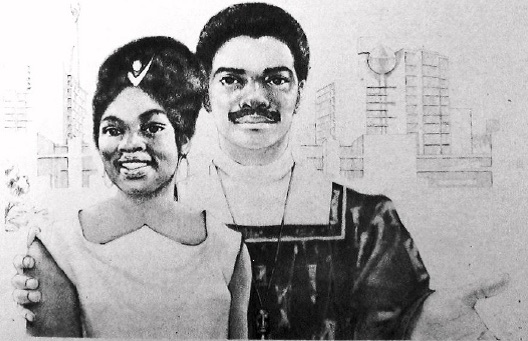

The illustrated couple stands welcoming, perhaps beckoning, members of the captive New Afrikan nation to join the struggle for independence. Resembling Christian faith leaders in their demeanor and posture, the two request willing laborers for a cause greater than what any one individual can achieve and for the elevation of all humans to a new material standard of living and dignity. To those who meet the request, a promised land awaits. Importantly, the promised land is not beyond the reach of humanity on the planet earth. No. The land is available to anyone who is willing to work toward New Afrikan statehood and the common cause of global revolution. Not content with offering unrealistic utopian fantasies to skeptical, though potential, participants, the two provide a concrete vision upon which volunteers can model their future communities and nation. The high-rise buildings behind them resemble the urban realities of many. Within that landscape, the couple is careful to offer kernels of hope within a familiar setting. Just behind the New Afrikan woman, a statue of a victorious figure rises from one of the buildings. Perhaps the building is a government headquarters where the New Afrikan leadership meet to chart the next steps in their ongoing revolutionary agenda, as an independent nation and as part of a multinational coalition. The New Afrikan woman embodies the victory of that agenda. Her proud smile and her headwrap bear the symbol that stands directly behind her. Rising from one of the buildings behind the New Afrikan man is a sphere or globe. Resembling the afro-futurist aesthetic of Sun-Ra’s Space is the Place, it may symbolize the results of a planetary power shift generated by the rise to power of previously colonized and oppressed nations. These two are partners in struggle. Their liberation is tied into the success of the nation, which is their most immediate goal, and liberation of the nation both depends on and helps to fortify the global revolution and creation of a new world.1

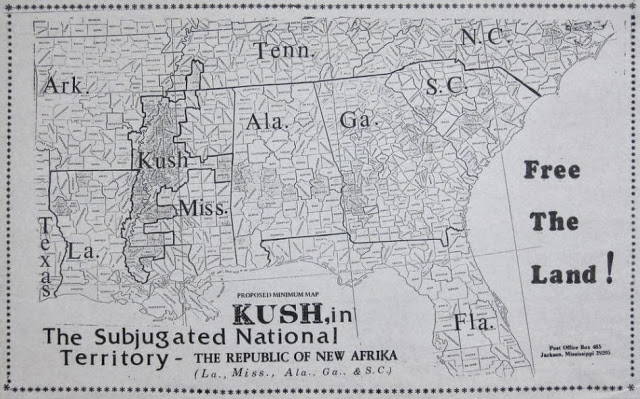

In 1968, the year the New Afrikan couple’s revolutionary mission began, the world was changing. New nation-states were forming as former colonies revised relationships between Africa, Asia, and the West. Some fought hard for their liberation, and some were still fighting. From Vietnam to Zimbabwe, bloody struggles against western capital and racist settlers clarified the tenacity white supremacy and imperialism. Other nations were “peacefully” exchanging white political leadership for parties and personalities rooted in local soil. All excited the US Black left which welcomed the changes as the ideal condition for their own liberation. Among them were activists who, beginning in March 1968, decided to pursue the creation of an independent nation-state that would occupy land in the US Deep South. Considering Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, and Georgia as the rightful territory of their Republic of New Afrika, those who championed independence sought to replicate the apparent successes of Tanzania and other newly formed states, while contributing to the complete overthrow of western hegemony.2

The ongoing New Afrikan struggle for land and independence is ripe with opportunities to explore how its advocates negotiated their African ancestry and a perceived colonized status with their distinctly American position within geopolitics. In asserting their right to self-determination, New Afrikans complicated the meanings of captivity and Third World solidarity in ways that were unique to the Black Power era but that continue to have resonance. Even as they built on the Black internationalism of predecessors, from the African Blood Brotherhood, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the Civil Rights Congress and more, and worked alongside their Black, Brown, and Indigenous domestic and international contemporaries, New Afrikans helped to put forth a vision of international decolonization as essential to Black liberation. Simultaneously, New Afrikans have viewed the destruction of western global hegemony as partially dependent on their own movement for land and independence. Therefore, they viewed solidarity between historically oppressed peoples as crucial to global revolution. Such ideas continue to guide the New Afrikan Independence Movement (NAIM) and provide a useful framework for anyone who is concerned with modern-day “Third Worlding,” or the creation of a geopolitical order that values the wellbeing of people and the planet over capitalist models of never-ending economic growth and the hyper-individualist accumulation of power and profits.

Visions of New Afrikan Independence and a New Geopolitical Order

New Afrikans began working toward their vision of statehood during the final weekend in March 1968 when hundreds of the leading activists and thinkers of their era convened in Detroit, Michigan to determine a new political agenda for Black people in the United States. Called together by brothers Gaidi and Imari Obadele, dignitaries of the Black nationalist left, including Betty Shabazz, Amiri Baraka, Herman and Iyaluua Ferguson, and honorable elder “Queen Mother” Audley Moore participated in the convention. Also present were dozens of other men and women who were playing important roles in their local communities and across the country. During their time together, participants discussed some of the most important topics of the movement. Everything from working with captured revolutionary activists and denoting them as political prisoners and prisoners of war to demanding reparations and struggling over sexism and ingratitude toward women in the movement received some consideration. The space they made for critical dialogue of this nature led up to the creation of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika and the discussion and acceptance of a declaration of independence. With Queen Mother Moore leading the way, well over one hundred people signed on. The document signaled their intent to guide their people to struggle for liberation and statehood. In addition, the document committed those who signed on to fight against “oppression wherever it assaults mankind in the world.” New Afrikan independence, therefore, was framed as a project of international solidarity and global revolution.3

These ideas took root within the strategies and tactics of the NAIM and would have implications well into the twenty-first century. In 1973, with the systematic imprisonment of many freedom fighters from the United States to South Africa and elsewhere, New Afrikans and their comrades from several well-respected organizations created International Solidarity Day for African Prisoners of War. Recognizing people at home and abroad who were imprisoned due to their political beliefs and their actions in pursuit of liberation, these activists helped solidify the foundation upon which ongoing efforts for the release of political prisoners would build. Activists put these activities in motion even as the Provisional Government was circulating its demands for financial restitution as partial payment to Black people for centuries of oppression, including enslavement and its aftermath of segregation, economic exploitation, and unrelenting anti-Black violence. The language of the New Afrikan reparations demand and the consistent efforts of independence activists helped bring about the 1987 call to establish the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. And through praxis around these and other issues, the Provisional Government and other New Afrikan formations such as the New Afrikan People’s Organization struggled internally to identify and challenge sexism within their formations. As with similar struggles in other organizations, such efforts were driven by the women in the movement and initially resulted in increased representation of women in key leadership positions. However, over time and in step with broader societal trends, efforts to destroy misogyny, sexism, and patriarchy continued to challenge activists to internalize the idea that simple visibility of women cannot replace much-needed comprehensive change. On all three fronts—political prisoners and prisoners of war, reparations struggle, and challenging sexism—New Afrikans continue to struggle.4

Paper-Citizens in the US Settler State

New Afrikan understandings of solidarity are rooted partially in the view that the Republic of New Afrika is the “captive” Black nation in the United States. According to the main theorists behind the independence movement, they are African-descended people who, due to human trafficking and enslavement, and ongoing racist and economic oppression, had been deprived of their original nationalities even as they continued to be victimized by the US empire. In other words, the Republic of New Afrika are those whom we commonly refer to as Black people or African Americans. At the same time, RNA theorists made space for more recent African and African-descended immigrants and non-African peoples. Japanese American activist Yuri Kochiyama’s New Afrikan citizenship is a prime example of how race and ancestry were not the only criteria for inclusion within the New Afrikan nation. New Afrikans have made claims to the five-state territory that also goes by the name Republic of New Afrika. Therefore, the RNA includes both people and territory.5

Gaidi Obadele explained that New Afrikans had a right to the five states based on legal analysis, historical study, and their understanding of repair. Accordingly, New Afrikans formed from a composite of various African peoples. As human commodities in the global trade of Africans, these disparate groups were forced together in bondage and enslavement. Theft of their bodies, labor, and intellectual gifts placed them in close proximity with assorted Europeans, as well as captives from Indigenous nations (some who also were enslaved and trafficked globally), and Native peoples who continued to variously negotiate between, collude with, and wage war against European settlers. As these groups came into contact, they built relationships through violence and assent (ostensibly) that led to progeny who, over time, formed a unique position and political group as a captive African nation in the United States.6

With this historical background in mind, the original New Afrikan independence theorists contended with the contradictions of being forced denizens within the US empire. Their claims exposed a number of important conditions that deserve attention. Foremost, is the New Afrikan claim that they are “paper-citizens.” The term indicates that, although federal law has considered Africans born in the United States as citizens, that legal designation belies a history of captivity and a forced, yet incomplete, inclusion within the US nation-state. Imari Obadele wrote that the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution ended the practice of legal slavery except as a punishment for a crime, effectively making African and African-descended people a free nation. At that point, they should have been given reparations for all that the United States and its citizens stole from them, and they should have had ample opportunity to determine what their best options were with regard to where to live and under whose government. However, New Afrikans have claimed that the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment robbed their ancestors of the power to make that determination on their own terms. Because the amendment applied the concept of birthright citizenship on them, it effectively recaptured Black people and made the briefly free nation vulnerable to continued violence and exploitation by actors at all levels of government. They were called citizens on paper; but in reality, they did not enjoy many of the rights and responsibilities that came with that designation.7

Being paper-citizens calls into question what it has meant to exist as an oppressed people within a settler colony-state. What has characterized the complicated relationships between African and African-descended peoples, European settler-colonizers and their progeny, and the diversity of Indigenous nations? It is commonly understood that the conditions through which New Afrikans began to struggle for liberation originated in a pan-European invasion and conquest of lands now called the Americas.8 Within the unfolding of “discovery,” settlement, and expansion, a number of historical imaginaries emerged. The mythos propagated from the view of the colonizer claims that noble communities escaping religious and political persecution arrived on “virgin” shores where they were able, through individual hard work, ingenuity within adverse conditions, and resilience in the face of ever-impending disaster, to build the most powerful and free nation the world has yet seen. In the process, they tamed “uninhabited” wild lands, produced the world’s leading democracy, and became the beacon of liberty for all who care to join in their honorable project.9 Historian Lorenzo Veracini makes clear that the establishment of the US nation-state depended on the constant negotiation of multiple relationships, not least those with “indigenous Others” and “abject Others.” African and African-descended people fall into the last category. He writes, “These people are disconnected from their land and communities, are the subject of segregative practices that are construed as enduring, and are principally characterized by restrained mobility (the absolute opposite of a settler capacity for unfettered mobility).”10 As victims and survivors of a settlement colony-state, the ancestors of self-proclaimed New Afrikans had to overcome the overwhelming challenge of existing in daily (re)negotiation with those who were in the process of forging and developing a new nation, as well as the Indigenous peoples who experienced genocide, dispossession, international enslavement, and a cycle of treaties, broken promises, and war. Under such conditions, the precarity of Black captivity was clear and helped guide New Afrikans toward a framework of solidarity that attempted to find justice and repair for themselves and those whom they identified as having common cause domestically and internationally.

Solidarity and the Praxis of Liberation

Because they were brought into the American project primarily as enslaved captives, African people’s position within the settler colony-state was complicated, and troubled how Africans would interact with their captors and with the Indigenous nations whose own dealings with European settlers were also complex. On the one hand, history shows the various ways that African and Indigenous peoples collaborated in opposition to a common Euro-American enemy. New Afrikans point to the development of the Seminoles as an important moment of solidarity and cooperation.11 On the other hand, this history is also saturated with examples of mutual mistrust and hostility. As historian Tiya Miles explains, some Indigenous peoples participated in the enslavement of Africans. There is also evidence that significant numbers of Black people were loyal to expanding white settlement and participated in wars against and massacres of Native peoples. Examples from pre-Civil War Texas to the Buffalo Soldiers during the era of General Custer’s campaigns in the American West confirm that not all African Americans saw it as in their interest to side with the Comanche or Navajo against forces such as Texas Rangers and the United States military.12 Honest assessment of the history meant that New Afrikans could not use myths about a perfect Black-Indigenous friendship to help justify their claims to the five-state territory. Instead, they had to develop a projection of their struggle that considered the reality of their historic condition while clearly laying out the possibilities of solidarity moving forward.

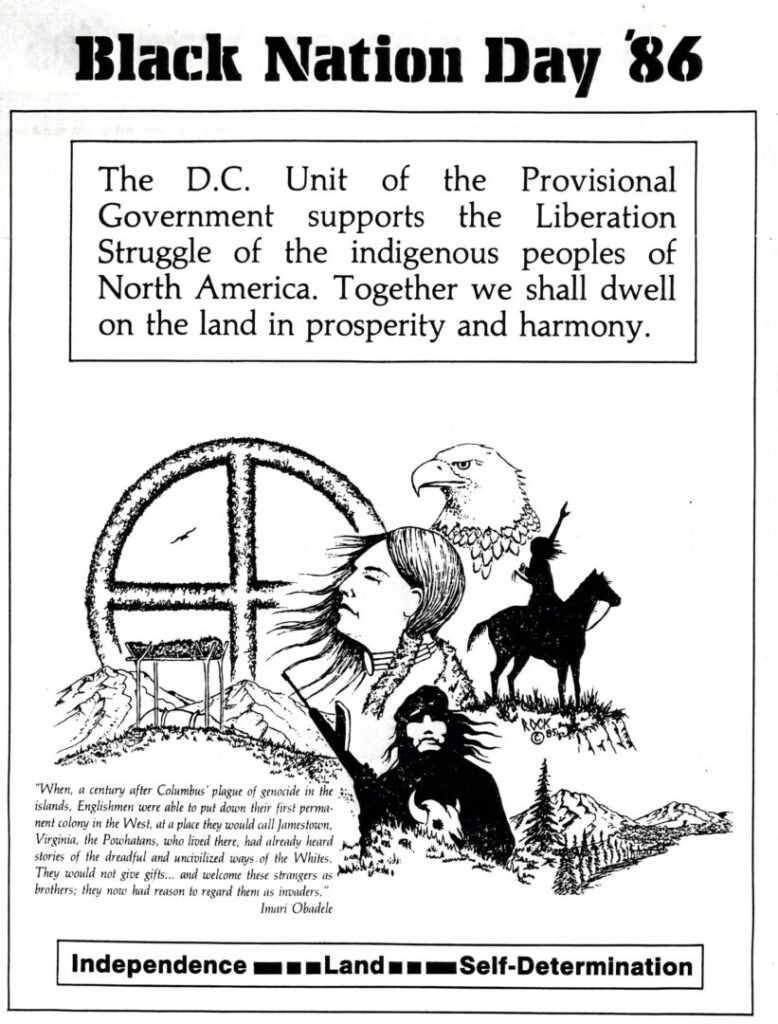

The Code of Umoja, or the New Afrikan constitution, attempts to do just that. Therein we see that “It shall be the policy of the Provisional Government to recognize the just claims of the American Indian Nations” which conflict with New Afrikans’ territorial interests.13 New Afrikan Ahmed Obafemi articulated the notion this way: “Soaked in New Afrikan blood and cultivated in New Afrikan labor, for three hundred years the birthplace of New Afrikan babies, and the burial places of New Afrikan ancestors, this land became New Afrika, portions of the land subject only to the just claims of the Native American population.”14 Both statements affirm the overlapping interests in the land, even as they put forth a vision of cooperation that could undermine the legacy of settler colonialism. Instead of fighting over stolen land, New Afrikans suggested a peaceful resolution. Importantly, the suggestions here do not and cannot fully restore either group to its pre-colonial status. Instead, repair put into focus the injustices perpetrated by European settlers as a way to anchor support for mutual claims and efforts at self-determination. According to Obafemi, “We must support each other in our drive to liberate our respective nations. In solidarity our respective liberation struggles must tear the guts out of this imperialist state, thereby serving our people, and indeed, serving the world.”15 In other words, because the United States has been a hegemonic global entity, successfully liberating the Republic of New Afrika and returning various lands to Indigenous nations would fatally injure the US empire. The successes of oppressed peoples in the United States would create opportunities for the colonized elsewhere to likewise overcome Western hegemony and build.

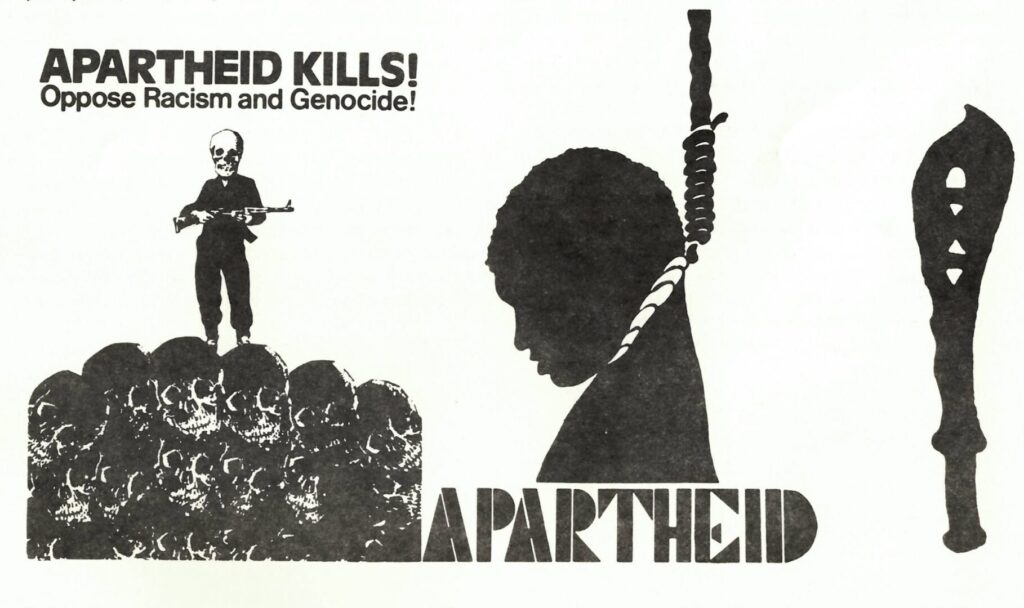

The ideas that New Afrikans wrote into their founding documents continued to resonate, even as the political conditions changed over time. From decades old New Afrikan print media to modern-day social media, onlookers can discern how independence activists have consistently theorized solidarity as key to global revolution and the creation of a new world. The New Afrikan Journal of the 1980s, for example, included an international section that offered analysis of how domestic oppression was just one aspect of worldwide white supremacy. Much like their counterparts in other Black Power era formations, New Afrikans remained attentive to brutality of US military campaigns abroad. Calling for a halt to wars of imperial aggression in Asia, Central America, and elsewhere, New Afrikans made clear that they stood in opposition to the US war machine. Besides being a driving force of imperial violence, US militarism also absorbed disproportionate numbers of Black youth, sending them to fight for Uncle Sam overseas as the US state continued to wage war against New Afrikans at home. By the 1980s the victory of Zimbabwe and the fever-pitched struggle against South African apartheid were visible in New Afrikan print culture.16

More recently, New Afrikans have used social media platforms such as Facebook and to highlight and encourage international solidarity. As part of its Black August Resistance programming in 2020, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM) hosted a panel of New Afrikan, Caribbean, and South American activists. It provided space for international and multilingual explanations of what was happening on the ground in the panelists’ respective areas; and the activists expressed and encouraged practical terms for maintaining solidarity while unifying around common issues and concerns. Importantly, this panel and the breadth of Black August Resistance online offerings were intergenerational, reminding viewers that protracted struggle requires the constant collaboration of elders and youth, even as they build relationships with comrades of various nations.17

These are just a few ideas upon which the diversity of current day intellectuals and organizers may draw upon for inspiration as they continue to challenge oppression domestically and globally. New Afrikan independence activists teach us that solidarity cannot be based on oversimplified narratives that ignore the very real harms that oppressed peoples have perpetrated against one another, either as active agents or as complicit bystanders. True solidarity must confront such harms, promote interpersonal healing, and encourage the reimagining of how the world may look in the aftermath of an interlocking and multifaceted struggle for the liberation of all. Although New Afrikan praxis took as guaranteed the existence of nation-states, modern-day activists must determine whether such formulations need remain in place. In fact, even within the NAIM, that question has come up. New Afrikan freedom fighter Kuwasi Balagoon was an anarchist who theorized New Afrikan and Third World liberation, even as he challenged the assumption that the nation-state must remain the primary mode of organization in the aftermath of revolution.18 New Afrikans’ historical praxis, along with independence activists’ modern-day efforts to build on the legacies of these revolutionary forebears, offer ideas that current-day activists can rework as needed to fill their specific needs.

Conclusion

The development of international solidarity among historically oppressed peoples has been a central key feature of the NAIM since its founding in 1968. As such, New Afrikans helped carry a black internationalist politic that preceded them from the Black Power era into the twenty-first century. Conceived during a moment of global anticolonial movements, the New Afrikan approach to solidarity was based on careful historical analysis and practical strategizing. As African and Asian peoples fought for independence on their own terms, New Afrikans sought ways to develop a praxis of liberation that would benefit all who were seeking to build new nations while simultaneously bringing an end to Western hegemony.The New Afrikan model of solidarity has the potential to inform the current efforts of people who are concerned with Third Worlding, in this case developing and maintaining mutually beneficial power relationships outside the capitalist and white supremacist framework. Working together across cultural and national boundaries is an important project for people who are interested in bringing about a society and world that is based on international cooperation, respect for human rights, upgrading human dignity, and slowing the devastation of capitalist-driven climate change.19 The New Afrikan Independence Movement offers one example of building international solidarity and stands in line with other Black Power era and modern-day efforts. The Black Alliance for Peace, Pan-African Community Action, independent media such as The Real News Network, and Breakthrough News, and more all provide complementary and highly accessible models for learning about and connecting to the global struggles against oppression. Like the most recent efforts of Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and other New Afrikans, they build upon a centuries-long legacy of activism while compelling us to continue the struggle for the creation of a better world.

Notes

- Space is the Place, directed by John Coney (San Francisco: North American Star System, 1974), 85 min., YouTube, https://youtu.be/bCalqwsicls. ↩

- The founders of the movement originally spelled Africa with a c. They began using the k in the mid-1970s. See Edward Onaci, Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 106–107. For Black Internationalism, see Charisse Burden-Stelly and Gerald Horne, “From Pan-Africanism to Black Internationalism,” in The Routledge Handbook of Pan-Africanism, ed. Reiland Rabaka (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 69–86; Minkah Makalani, “Internationalizing the Third International: The African Blood Brotherhood, Asian Radicals, and Race, 1919–1922,” Journal of African American History 96, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 151–178; and Cynthia A. Young, Soul Power: Culture, Radicalism, and the Making of a U.S. Third World Left (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006). ↩

- “Congressional Hearing, ‘Riots, Civil and Criminal Disorders,’” reel 16, ser. 12, frames 397–402, RAM; Proposal: The Provisional Government,” reel 10, group 1, ser. 4, frame 138, ROB; and The Republic of New Afrika, “Declaration of Independence,” Courtesy of General Kuratibisha X Ali Rashid. ↩

- Letter from Leslie Ann Tolbert, 19 February 1973, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Box 1, Series 1, Folder 2; National Coalition of Blacks For Reparations in America, “About Us,” http://ncobra.org/aboutus/index.html; Republic of New Afrika, “Declaration of Independence,”; and “Revolution without Women Ain’t Happening,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bsrk4hBtVeA. ↩

- Onaci, Free the Land, 59–71; Diane C. Fujino, Heartbeat of the Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2005). ↩

- Gaidi Obadele, “An Independent Black Republic in North America,” in Black Separatism and Social Reality: Rhetoric and Reason, ed. Raymond L. Hall (New York: Pergamon, 1977), 33–39. For historical analysis of this process and its accompanying violence and theft, see Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1998); and Jennifer Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004). ↩

- Imari Abubakari Obadele and Atty. Gaidi Obadele ({slave name} Milton R. Henry), The Article Three Briefs: Establishing the Legal Case for the Existence of the Black Nation the Republic of New Africa in North America, June 25, 1973, 13–21, courtesy of Ukali Mwendo. For the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, see Constitution Annotated: Analysis and Interpretation of the U.S. Constitution https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution. ↩

- For example, see Gerald Horne, The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in Seventeenth-Century North America and the Caribbean (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2018). ↩

- Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, December 14, 1893, esp. 221–222. ↩

- Lorenzo Veracini, Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (London: Palgrave Macmillan Publishers Limited, 2010), 28. ↩

- Akinyele O. Umoja, “Settler-Colonialism and the New Afrikan Liberation Struggle,” The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2019), 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91206-6_78-1. ↩

- Tiya Miles, Ties That Bind: The Story of An Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005); Kenneth Wiggins Porter, “Negroes and Indians on the Texas Frontier, 1831–1876,” The Journal of Negro History 41, no. 4 (October 1956): 285–310; Theda Purdue, Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700–1835 (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998). ↩

- The Republic of New Afrika, The Code of Umoja, courtesy of General Kuratibisha X Ali Rashid. ↩

- Ahmed Obafemi, “Building Strategic Alliances and People’s War: National Liberation Inside the u.s. Imperialist State,” in New Afrikan Institute for Political Education, Toward the Liberation of the Black Nation: Organize for New Afrikan People’s War!, 1981, 17–22, Freedom Archives Online, https://www.freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC515_scans/515.naipe.peoplesWar.81.pdf. ↩

- Obafemi, “Building Strategic Alliances.” ↩

- For example, “Provisional Government Demands U.S. Halt Panama Aggression, Dis-engage Black Troops and Pay Reparations,” The New Afrikan Special Issue (Spring 1990): 14, courtesy of Nkechi Taifa; “The National Committee for Pan-Afrikan Democracy and Prosperity Host His Excellency and Our Brother Robert Mugabe, Prime Minister of the Republic of Zimbabwe,” The New Afrikan Journal, no date, 27, courtesy of Nkechi Taifa. ↩

- Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, “International Solidarity: Connecting Struggle for Self-Determination” August 17, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/events/678409293021275. For international news and multi-national solidarity from New Afrikan Independence Movement perspectives, see also Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, BAMN News Journal, https://freethelandmxgm.org/media; and Xinachtli (Alvaro Luna Hernadez), “Statement of Solidarity,” Re-Build 2, no. 2 (Winter 2020/21): 6–7, https://www.rebuildcollective.org/events-1. ↩

- See Kuwasi Balagoon, A Soldier’s Story: Revolutionary Writings by a New Afrikan Anarchist, 3rd ed. (Montreal, Quebec: Kersplebedeb Publishing, 2003); and Akinyele Omowale Umoja, “Maroon: Kuwasi Balagoon and the Evolution of Revolutionary New Afrikan Anarchism,” Science & Society 79, no. 2 (April 2015): 196–220. ↩

- Ron Whyte, “Why We Should Care About Environmental Justice,” BAMN News Journal 1, no. 4 (December 2019): 22–24, https://freethelandmxgm.org/2020/06/bamn-vol-1-issue-4/. ↩