The Cruise Ship as Campus

In 2016, the Crystal Serenity became the largest luxury cruise liner to sail the northwest passage above North America.1 This sea route linking the Atlantic and Pacific ocean has been unnavigable for centuries due to unpredictable variations in Arctic sea ice. But warming northern waters now welcome a new era in Arctic tourism that seeks to showcase remote indigenous communities and pristine glaciated landscapes even as they are threatened by climate change in the new century. In fact, threat is the appeal of the spectacle. Michael Byers refers to this new type of high-end travel as “extinction tourism” where travelers seek to experience species, cultures, and landscapes as they confront environmental crisis, a crisis born of high-fuel emission activities such as the cruise ship industry itself.2 Contradictions such as these once served as a ready point of departure for critical pedagogy, but where does one begin once the critical ironies of capitalist processes are overshadowed by their sheer marketability?3

Meanwhile aboard the Crystal Serenity, pedagogy abounds. Crystal Cruise Lines offers passengers access to the Creative Learning Institute which partners with the Cleveland Clinic, Tai Chi Cultural Center, and the Society of Wine Educators to bring comprehensive instruction in languages, music, wellness, and art.4 The Institute features programs with celebrity experts who offer TEDx-like lectures in a range of categories. Many luxury cruise lines now incorporate enrichment and educational programs as part of their sailing experience, and cruises can be found incorporating specific themes like cooking, computers, history, finance, astronomy, or art.5 Colorado State University’s Semester At Sea offers college credit to 1,500 undergraduates a year across seventy-five courses in humanities, business, and science. The floating campus of the MV Explorer, complete with classrooms, computer labs, and a nine thousand volume library, claims to make “the world your classroom” by circumnavigating the globe twice a year, making stops in different regions of the world in conjunction with course syllabi.6

The image of floating campuses networking learning environments around the world denotes how “knowledge economies” have made any dissociation between education and economics untenable.7 With the transition from Fordism to flexible accumulation, as universities shift from national to international protocols to redefine their operations, scholars have mapped the contours of an emergent hegemonic education paradigm that removes the logistic clash between democracy and market demand, links the interests of the state with global capital, and positions students as entrepreneurial actors in every sphere of life.8 Although implemented as a measure of social control and a reaction to perceived political fears after World War II, the mid-century cultural institution of the American university initiated affordable and accessible mass education as a functional cornerstone of democracy and articulated a form of liberal arts motivated by preparing a diverse citizenship capable of engaging national and international problems as its prime objective.9 Facing economic and cultural realities of neoliberal governmentality, the same institution now reframes knowledge, thought, and training toward developing human capital, and higher education now adopts corporate protocols to define its content and purpose, physical appearance, financial structure, evaluation metrics, management style, advertising, organization, and promotion.10

The impact of this evisceration of a mass liberal arts education over the past forty years demands ongoing rigorous attention. Equally important will be avoiding the paralysis of pedagogical imagination that follows from this expanded role of education as an instrument suturing globalized urbanization and the nation-state to neoliberal economic policy. I want to suggest that the conversion of students and state universities into subjects of the economic imagination works both ways, and knowledge production today—in the form of Crystal’s Creative Learning Institute, as much as biometric turns in organizational studies, quantifications of selfhood, smart cities, and parametric urbanism, to name a few—arises as a staple of economic value and a driving force of global production and consumption processes, while the university itself, far from crumbling in ruins, ascends as a key protagonist in the development of multinational economies, globalized urban space, and prestige networks for individual success.11 In an era when urban space is theorized as an educative science to enhance productivity, business, and management, we witness the act of educating, perhaps for the first time in the history of capitalism, as a dominant productive force of economic expansion.12 Indeed the advent of knowledge economies references the scale to which education mediates the spatial restructuring of nation-states into new global economic regimes harnessing flexible systems of accumulation and broad interdependent networks, transnational migration, and regional urban development premised upon deterritorialized flows of capital, often anchored precisely by university and corporate campuses that distinguish regional cultures.13 In this historical context, a critical pedagogy must emerge from how the material and discursive production of education practices, whether on cruise ships, college campuses, or “cities of knowledge,” instantiate social relationships that have implications for the state’s formation, or disintegration, in regard to processes of globalization and neoliberalism.14 If the cruise ship today is a metonym of the corporatized campus, we may do well to search for such a critical pedagogy within its unique spatial formations in which multinational capital functions omnipresently over local decisions, governments, and urbanization.15

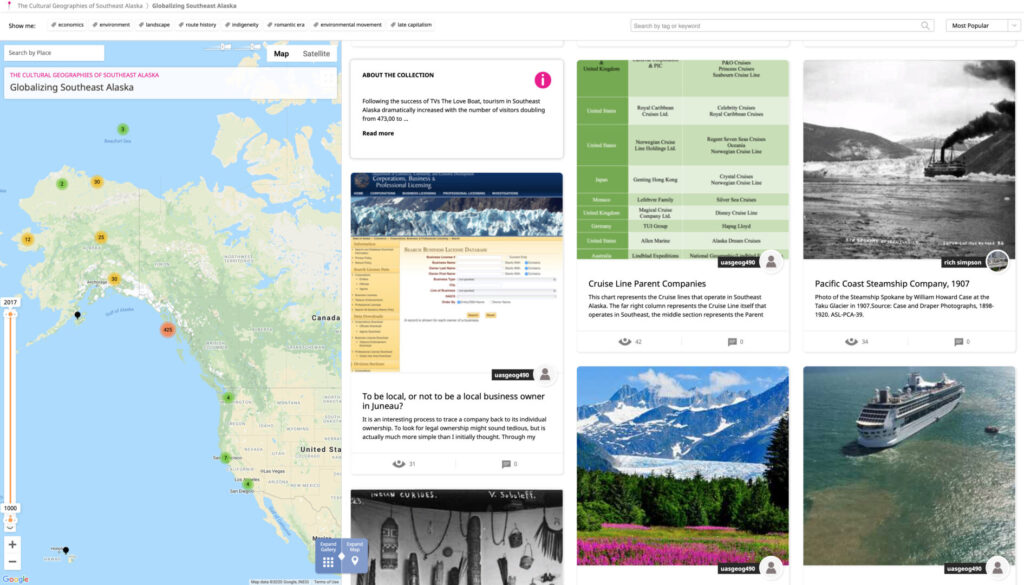

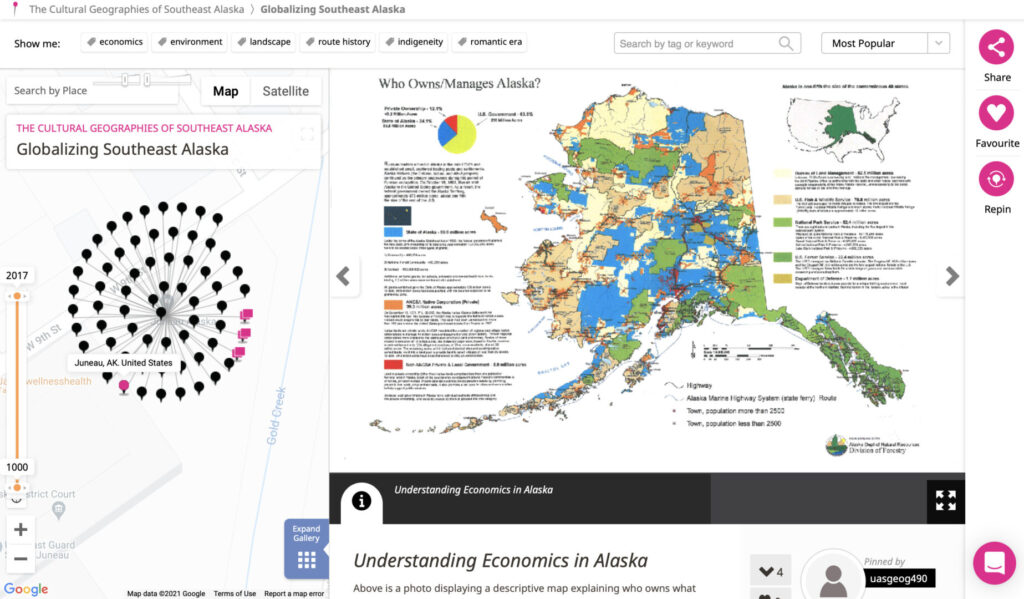

At the University of Alaska Southeast, my students and I approach the transformation of downtown Juneau as an argument and contestation over the right to the city, as well as an active public discourse producing and circulating polemical images and popular practices of a region currently in the throes of cruise ship “touristification.” Identifying the specific contours of this living process—framing the cruise ship industry as a constitutive system fusing discourse, urban space, and social identity to restructure local history, nature, and region—became a means of questioning and revising the otherwise generalized theories often brought to bear on tourist landscapes, on Alaska, and on critical pedagogy itself. Over the course of a fifteen-week semester, our digital cartographic website, entitled Globalizing Southeast Alaska, became an active space for political formation and the collective production of knowledge as students engaged the impact of cruise ship tourism—that is to say the cultural, rhetorical, and material resonance between their everyday lives, abstract flows of the global economy, labor, and state, federal, and international policy in southeast Alaska—as constitutive of spatial inequalities, uneven social relations, and systemic racism and classism. My purpose in analyzing this project in this article is to extend its productivity, to learn something from it, which is the goal of pedagogical practice, by applying its lessons not so much as a model of critical pedagogy, but as a cultural practice for a particular place and time. The cartographic itineraries of the Crystal Serenity seizes opportunities for remapping the northwest passage and establishing a future that monetizes the newly accessible landscapes incurred by climate change while at the same time doubling down on the logic and impact of carbon capitalism (see Figure 1).

The following counter-mapping project confronts this form of globalized urbanization by forging a progressive classroom practice that merges the digital with the residual materials of tradition and nostalgia animating the regional rhetorics of Alaska.

In the following case study, I use critical regionalism to frame a digital pedagogy capable of establishing three discursive connections or “joints”: first, students’ own spatial knowledge about their home and everyday life situated within their own struggles over space as it pertains to class, race, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity; second, the non-representable, abstract processes of late capitalist globalization; and third, the situated discursive and material rhetorics of space in southeast Alaska. In the act of mapping these connections, my students identify the ways their own lives are interpellated into a place-making process in Juneau, both as local subjects and objects of global determinations, and they develop a sense that they are a part of social and political change. I pay particular attention to the process of student collaboration to examine visual spatial tactics as instruments that facilitate shared knowledge, collective interpretive framing, and political formation. I conclude by addressing the educative potential of a critical regionalist pedagogy as an interdisciplinary and transnational educational theory for analyzing the interurban rise of the cruise ship city and neoliberal global formations.

The task of a transformative pedagogy involves the reconfiguration of the relations of dominant spatial processes, the necessity to reinvent urbanization in ways designed to maximize human freedom. This involves much more than democratic access to public resources such as education. In The Right to the City, Henri Lefebvre insists that access and equal distribution are not enough—the ultimate political stake involves the collective right to engage landscape as an artistic human practice, that is to say as a pedagogical project, which includes the potential to make and remake identity and collectivity itself.16 In this work, I identify the way in which the right to the city includes the act of writing the city. As such, I show how a critical regionalist pedagogy contributes to an understanding of urbanization as a social right by creating a learning process whereby students write the city as a social production, and in doing so, grasp urbanization as indispensable to social change through its capacity to link global relations, practices, and structures to the struggles of everyday life.

Toward a Critical Regionalist Pedagogy

In his analysis of the cultural logic of global market capital, Fredric Jameson asserts that one of the integral features of postmodernism is its open tolerance for an aesthetics of didacticism, and as such, the work of identifying creative and critical possibilities within this expanded realm of art and culture becomes urgent.17 Given the pervasive educative motive embraced by the cruise ship industry, and multinational capital in general, it becomes necessary to distinguish sites of teaching not solely in terms of their ideological position, but also in terms of their relational position, that is, the way historical, social, and lived dimensions function within a setting as a productive and constitute practice. As such, in the era of globalization, new organs of analysis capable of relationality and association become vital, and regionalism has emerged as a valuable spatial category precisely due to its mediating role between urban, national, and international signification. Through a rhetorical lens, region does not mark a bounded space or territory, but rather emphasizes what Doreen Massey calls “relational space,” or heterotopias characterized by relationships between and among places.18 Massey argues against neatly defined distinctions between the local and global that are implied when scholars theorize global cities as having a particular set of distinct properties. Instead emergent spatial forms of globalized urbanization demarcate dialectical relationships between collective actors through a variety of global, regional, and local flows that actively negotiate these scaled topographies.19

Building on this relational approach, critical regionalism has emerged as an aesthetic paradigm across a range of disciplines, a development that may signal its value as much as its failure, given that this polemic was precisely called upon to challenge disciplinary boundaries.20 Yet theoretical emphases on relational flows and practices over and against static conceptions of place and identity have proven to have limitations. Barbara L. Allen calls for a rethinking of theoretical approaches to critical regionalism by implementing performative modes of action in which place is given meaning based upon the unique forms of relationships that geographically locate identity.21 Allen takes up Judith Butler’s performative theory to push beyond simply identifying scaled flows, activities, and practices as a basis for conceptualizing place-based identities, and toward directly addressing the “glaring omission” that socially-constructed “practices” and “interactions” remain under-theorized and under-represented in the body of regionalist and critical regionalist literature. “What is needed,” writes Allen, “are more robust tools for understanding the intersection of cultural practices and regional places.”22

The concept of “region” has additionally received attention from urban studies where scholars have sought place-based approaches to the global city. Ananya Roy argues that area-based knowledge deepens theoretical attempts to articulate a relational study of space and place and that theories of the global city must be developed in specific places and require a “rather paradoxical combination of specificity and generalizability: that theories have to be produced in space (and it matters where they are produced), but that they can then be appropriated, borrowed, and remapped. In this sense, the sort of theory being urged is simultaneously located and dislocated.”23 This dilemma of representing that which is located and dislocated, I argue, involves the sort of theory that may also be called an allegory. That is, a way of producing the placed-based specificity of contemporary global interurban networks as well as the material transformations, consequences, and implications of their dislocated practices. These interventions demand pedagogical tools that conjoin seemingly oppositional forces of material forms and discursive practices within a specified placed-based approach to dislocated processes of globalized interurbanization.

To advance these lines of research seeking to strengthen regionalist approaches to global urbanization and to develop critical regionalism as an interdisciplinary pedagogy, I want to briefly examine Fredric Jameson’s discussion of this “architecture of resistance” to address how its intersectional dynamic may differentiate an aesthetic practice outside the ideological constraints of postmodernism.24 In The Seeds of Time Jameson identifies critical regionalism’s repudiation of corporate hegemony, yet notes that this aesthetic does not seek recourse within the provincial as in the sentimentalization of the local one finds, for example, in the practice of neoregionalism.25 Instead, the residual practices and traditions of a region, or culturally coherent zone, that stand opposed to the homogenizing processes of globalization are taken up as the very means to establish an environment where “the body as a whole is seen as being essential to the manner in which it is experienced.”26 The link here between the representational space of the body and the experience of the body, or between the visual and experiential, becomes a productive or constitutive practice. Indeed this relationship between the visual/representational and the tactile/experiential becomes Jameson’s primary interest in critical regionalism, as it does not aim to pin these variables against each other, but rather offers a language that permits us to reconfigure their synesthetic relationality in a number of unexpected ways. Critical regionalism challenges the primacy of the visual by shifting attention to the non-representational category of the pressurized joint as the primordial element of architecture and indeed of space itself. Any building, structure, or space comes into being precisely through the configuration of a set of fundamental tensions locked into a play of union and disunion in which one material or system exists and gives way to another. In drawing attention to the relation of oppositional forces that brings a site into being, critical regionalism opens an interpretive practice of architecture and landscape that avoids isolating any one category, or system of knowing, and prioritizes the diverse range of oppositional, yet telluric conditions of the site itself as fundamental to its composition. The goal is not to establish realism or authenticity of the local, but rather to site locations in such a way that constitutes the act of acknowledging spatially and temporally limited compositional factors at work in the production of space and its modification.27

Jameson’s formal assessment of critical regionalism’s differentiation from postmodernism provides a pedagogic method that integrates a place-based conjuncture of diverse registers—scientific principles, metaphor, materiality, and affect—conventionally held in opposition to one another or rejected outright as inauthentic. This practice identifies forces in opposition as its constitutive structural framework, marking a conceptual shift toward identifying moments of both collaboration and disjunction, as a means to identify an interdisciplinary pedagogy capable of relating systems of knowledge otherwise perceived as incompatible. Diverse knowledge systems and scaled relations are inescapable site-specific determinants of any critical regionalist practice, and therefore before addressing my case study, it is necessary to articulate the regional rhetorics that site this neogeographic project within the constraining forces of a particular time and space.

Late Capital Juneau

One of the premises of this essay is that educative spaces or pedagogical landscapes, such as what I am calling the cruise ship city, have emerged as imaginary geographies necessitated by current forces of production and the structural practices of contemporary urbanized globalization.28 Representations of space as ‘frontiers’ or ‘hinterlands’ outside the reach of capital are inaccurate and deceptive.29 Narratives about the periphery, however intensely authored by the cruise ship industry, must in fact be grasped as dominant mechanisms subordinating space to capital, and analyzing this located and dislocated process strengthens our theorization of globalized urbanization among, within, and beyond studies of New York, Mumbai, and London.30

In 2019, cruise ship tourism marked the fastest growing segment in global travel with an increase of 8.4% per year in the number of passengers worldwide.31 In the past decade, tourism has been southeast Alaska’s largest private industry both in terms of jobs and workforce earnings.32 Since 2016, 90 percent of all tourists arrive in Southeast by cruise ship. Over the past five years, downtown Juneau, the state capital, overhauled its entire commercial district to prioritize tourism and cruise ship travel as a source of economic prosperity premised upon the income of visitor shopping, commercial passenger vessel revenues, employment opportunities, and lodging and sales tax ushered in by expanding the capacity and frequency of cruise ship tourism.33 With this goal in mind, city officials financed a complete reconstruction of the downtown marina to vastly increase ports of call and to accommodate larger cruise ships by installing floating Panamax docks capable of supporting two thousand-foot ships at a time, repaving streets and rerouting traffic to produce commercial corridors for tourists, and commissioning a series of artworks, sculptures, museums, tours, way-finding systems, and a mile-long Seawalk leading to a forty-five-foot bronze statue of a humpback whale breaching an infinity pool overlooking the channel (see Figure 2).34

Juneau maintains a population of 32,000 people, and between the six months of May and October, the city receives one and a half million tourists from approximately 600 international cruise ships.35 In a historical moment marked by depreciating oil prices, this restructuring toward the spatial vernacular of cruise ships has been given a legitimized sheen, even as money generated by tourism remains a marginal percentage of the state’s income.36

Yet this spectacular urban investment designed to attract larger and more frequent cruise ships occurs at the same historical moment as the full-blown dismantling of state services, including Head Start, Medicaid, public transportation, cruise-ship pollution oversight, mental-health services, and higher education. Governor Mike Dunleavy introduced these cuts in an effort to increase the annual oil revenue dividend that the state pays to every resident, thereby shifting state support for public resources into the decisions of private individuals resulting in a complete transformation of the production of space in Alaska.37 For example, the state’s drastic reduction of the ferry system will be fatal for many rural communities in the state who rely on marine transportation forcing these populations, many composed of Alaskan Natives, into the three major cities of the state.38 While national media coverage readily documents the relocation of Alaskan villages as a result of geographic effects of climate change, often incorrectly constructing narratives of disempowered Alaskan Natives, many more will be forced into displacement due the reduction of funding to the state ferry system.39 Thus with a struggling state economy, government officials utilize the urban core of Juneau to secure Alaska’s hand as a top destination for Carnival, Norwegian, and Royal Caribbean, while simultaneously eliminating state services and public resources, systematically undermining the needs, access, and survival of Native populations throughout the state. The increasing mobility of tourists in and out of the state weakens the already precarious position of rural communities in Alaska, and one wonders what options the state will provide displaced residents facing higher costs of living in the urban centers with reduced state services. Additionally the primary means of socio-economic mobility, higher education, will be less accessible and available. The University of Alaska, the education system in which I currently teach, has been issued a $70 million budget cut, forcing the university to declare financial exigency and the board of regents to initiate a task force to consolidate three regional institutions—located at Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau—into one accredited university. In the summer of 2019, John Davies, the UA board of regents chairman, described the state university system as “grappling with survival.”40

“Survival” is not simply an economic issue in Alaska as the term carries environmental, cultural, and colonial dimensions as well, and given our focus on points of oppositional forces, the rhetorical figures at work defining this region at a particular historical moment substantiate the raw material from which a critical regionalist pedagogy must emerge. As we have already seen with “extinction” tourism, “near-death” and “survival” are given increased cultural purchase in an era defined by environmental crises. Susan Kollin identifies this trope of survival as central to the literary and cultural history of Alaska, whose regional identity, often premised upon the depiction of a place removed from the rest of the world, now deploys a setting of extremity that provides cultural value to adventures in remote regions. Film and television shows such as Grizzly Man, Into the Wild, and Survivor, and the recent surge of extreme sports such as climbing Denali, heleskiing, and Arctic surfing, have become wildly popular cultural phenomenon premised upon human encounter with extraordinary places, animals, and landscapes. Access to treks into the wild characterize a popular outdoor lifestyle, once the basis of a counterculture resistance, that grant consumers—typically white, affluent men who need not worry about any other form of physical survival—a high degree of cultural capital. Kollin situates these narratives and representations by reminding us that, just as Western imperialism was originally shaped by economic expansion into the interior of the Arctic, today the popularity of extreme adventures further expands capital’s domain into the last remote enclaves of untouched nature, now prized for their ideological position as seemingly closed off from the rest of the world, thereby charging voyages of survival as powerful rhetorical devices capable of concealing the material, economic, racialized, and gendered bias of such “natural” encounters.41

While these experiences on modernism’s imagined periphery reveal social privilege, they also register larger geo-economic practices which no longer situate Alaska as a remote enclave of Western imagination, but rather as a central battleground of oppositional forces that permit a clearer understanding of the circuits of production and consumption of global capital. As fleets of cruise ships look to subsume new territories in the subarctic to stage encounters with the extreme species and spaces, we find new narratives of “interiority” in which human development and socialization are possible only through encounters at the boundaries of the human and non-human. We may consider Into the Wild and Grizzly Man as representations of cultural expansion in which humans attempt to push further and further into an interior space. While Chris McCandless’ and Timothy Treadwell’s experiences fit the genre of the “Alaska death tale,” they are more precisely stories about the desire to connect with nature, and in the process, die by or as food sources in the Alaskan wilderness. McCandles unknowingly foraged Hedysarum alpinum seeds which contain deadly neurotoxins and Treadwell mistakenly imagined a kinship with grizzly bears which led to his mauling and consumption.42

In each instance, surviving involves reaching toward a new reality, one that extends inward as an attempt to “find oneself by losing oneself,” or outward, to forge a domestic relationship with wild species. In such acts of survival premised on an imaginary, remote, and interiorized space located deep in the Alaskan backcountry, we glimpse a desire for forms of knowledge that have been scrubbed of cultural influence as ideas of unspoiled nature come to define the character of this extra-aesthetic, nonmeaningful locale. This imaginary extra-urban interior zone premised upon scenes of survival open the hope for a kind of anti- or pre-modernist space.43 Yet this desire to commune with an imagined interiority is of course no less stylistically produced than the urban metropolis it seeks to condemn.44 In representing Alaska as a wild and timeless region, this last ‘frontier’ now conjures a secular sacredness that isolates this place from human history and in doing so inscribes familiar narratives of ‘discovery’ that historically legitimized Western capital development and the dispossession of land from Native populations through scientific discourse.45 Thus we find the trope of survival now pedagogically motivating a range of political ambitions from the desire to locate a last vestige of interiority removed from urban decay and cultural influences, to the narratives of extinction that justify settler colonial practices, to doom tourism providing education and entertainment value for a multinational cruise ship industry.

Without a space for the social production of nature—that is, a concept of human freedom and social development through production and reproduction of the earth—the desire to imbue a deep and vast interiority with stories of survival, in the name of antidote or industry, brutally subordinates these spaces to capital where one is then forced, by capital, to have no choice but to neurotically eat away at the borders of the human and non-human. These two documentaries, perhaps the most viral representations of Alaska in late capitalism and undoubtedly responsible for increased tourism, anticipate the kinds of cross-species exchanges that now occur on a much larger global scale through intensified agribusiness expansion in the global south which induce the development of exotic species on wet markets, seemingly causing zoonotic transfers of the kind originating COVID-19.46 Indeed this urgent desire for survival in the interior hinterlands arises precisely as both a counter-therapy to intensified urbanization as well as a commercial and industrial operation that exposes the overlapping interface between socio-economic production and the biological substrate of the natural world. We cannot understand or experience nature today apart from global production and consumption demanded by capital. Alaska’s current dominant thematic of hinterland survival becomes a powerful discourse contributing to its urbanization as a theater of human engagement with macro- and microbiological organisms that erode the boundaries between the human and non-human world as if both were not already immanent to the global market.47

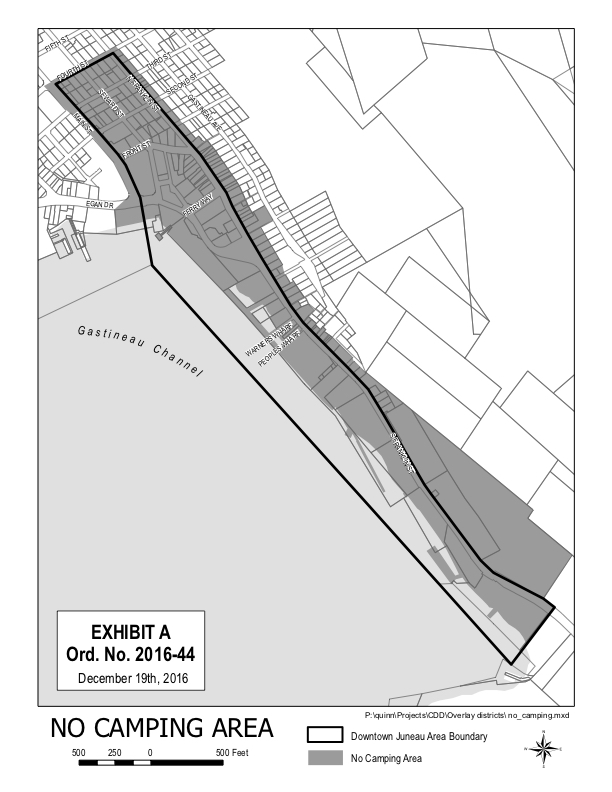

Narratives of survival in Alaska may thus be understood as formative of what Jessica Enoch calls the rhetorics of space or “those material and discursive practices that work to compose and enhance a space.”48 In the pedagogical section to follow, I show how my students began the semester by collecting patterns of the regional rhetorics of Juneau and how they forge relationships between cultural activities, urban planning, city, state, and federal policy. These material and discursive practices compose a rhetorics of space that create the urban core of the city, and students engaged this composition to map the way identity in Alaska, including their own, is edified and produced in the current historical moment.49 While Alaska’s representation of an imaginary biosphere outside urbanization inculcates survival-within-a-vast-interiority as a form of cultural capital, it also has consequences beyond the privileged practices of recreation, education, and self-discovery. On a local scale in Juneau, this discourse bears upon even those who do not seek the outdoors but are forced to survive outdoors, as they too are reframed through this popular language of recreation. The massive urban redevelopment of the Juneau marina required the removal of the city’s homeless population away from the major commercial thoroughfare of downtown to erase the unpleasant sight of the destitute and eliminate the harassment of tourists within the shopping district. To do so, city officials enforced what they called a “no camping” ordinance allowing the police to evict people sleeping on private property in specific districts downtown (see Figure 3).50

In addition to proximity to free meals provided by the Glory Hole kitchen, the homeless have historically congregated downtown once the tourist shops close in order to turn the entryways of diamond, souvenir, and T-shirt stores into temporary sleeping quarters due to the stream of heat that leaks through the cracks of their entryway doors. The forced removal of the homeless from resources downtown is then neutralized by determining homelessness as a personal choice, as simply choosing a recreational lifestyle.

Given that the majority of Juneau’s homeless are Alaskan Native, the no-camping ordinance may be understood as a regional spatial practice, or “specific social formation” of the settler colonial structure in which an indigenous population is effectively dominated and displaced on Native land.51 The particular insidiousness of the no-camping ordinance is the way the language of leisure is deployed to validate the colonial structure and entrench this urban landscape with a policing apparatus that serves the interests of the cruise industry to an unprecedented degree. By extending the idea of camping to include the activities of the most precarious segment of the city’s population, homelessness is identified by the state as a lifestyle practice on par with any other extreme outdoor activity. Hand-to-mouth survival in the alcove of diamond stores becomes relative to the risk of skiing black diamond slopes. By reframing a multi-million dollar urban infrastructure as a wilderness campsite, homelessness in Juneau can be associated with Alaska’s recreational lifestyle, not a failure of the state to provide resources, employment, mental health service, and affordable housing to its citizens.

Identifying the homeless as campers enacts a rhetorics of space through framing modes of belonging and thus may more accurately be understood as a regional rhetoric of space.52 This discourse of outdoor recreation is not simply the imbrication of the ideological aesthetics of REI and Patagonia onto Alaska, but a discursive practice that effectively shapes the material landscape and thereby determines who can and cannot survive within this urban setting. In addition to the no-camping ordinance, we witness the full force of outdoor lifestyle narratives on the lives of Alaskans when we ask how the state ranking second in the nation for methamphetamine deaths, holding the highest suicide rate, and having double the national average of rape and sexual assault today emerges as a premier destination for self-discovery and an escape from the ills of urbanization and all of the alienating effects of modern society.53 In the face of these sobering statistics, the portrayal of Alaska as a pristine wilderness and natural environment indeed requires a profound act of imagination. Any regional studies today thus requires a means to integrate such local contradictions within the framework of larger historical and social processes and their implications.

Having provided an overview of how regional rhetorics of southeast Alaska function as educative spatial strategies contextualizing the project, I turn now to my implementation of a place-based interdisciplinary pedagogic approach to digital counter-mapping that seeks to address how a multinational cruise industry actively produces material, social, and political effects on the way both tourists and Alaskans think and act in this landscape. My students and I wanted to map the rhetorical process by which multinational cruise ship corporations actively create textual representations about Alaska today, and in doing so, shape and construct the landscape, identities, and practices of the state in a moment of environmental crisis. The object of study became defining the specific forces of opposition within circulating discourses, individual needs, and spatial power-geometries that are articulated in the social relationships that define southeast Alaskan tourism. By actively siting the cruise ship industry as a constitutive system producing discourse, materiality, and social acts that restructure history, landscape, and tradition, students enacted visual spatial tactics to develop collaborative formations of shared knowledge, interpretive regionalist framing, and ultimately their own political formation.

Juneau Visual Spatial Tactics

The distinction between strategy and tactic outlined in Michel de Certeau’s Pratiques Quotidiennes (1980) remains a powerful means of analyzing the intersection of practices and places.54 Strategy describes the calculation of relationships that physically “take place” and, as such, advantageously positions itself to manage and influence future relations. Strategy presupposes the formation of a sustained power through a “congealed historical configuration” and, once given a proper place, establishes a readable environment that legitimates educational or ideological practices and ultimately determines the social characteristics of knowledge itself.55 The culmination of Juneau’s urban revitalization described above in which a transnational cruise industry, city developers, and state policy restructure land use and urban space to accelerate and intensify global capital pathways into the city are projections of de Certeau’s concept of strategy. Maps also derive power precisely from the rhetorical weight of abstracting socially contingent relationships and making them strategically appear as stable hegemonic representations of territory and property. Scholars and activists have responded by developing a practice of counter-mapping, allowing those that live in a mapped area to create representations of themselves by developing place-making practices that often challenge and subvert the categories of intelligibility of traditional cartography.56

As strategies imply hierarchies of power, they generate corresponding tactical practices. Tactics have no proper place and no autonomy as they are predicated on the absence of power and therefore mark momentary misuse of an existing imposed upon terrain. As kairotic gestures, tactics advance opportunistically in relation to the present set of power relations, much like the way the Juneau homeless use the alcove of a jewelry store as a temporary place to sleep. De Certeau regards tactics as acts of evasion or resistance by marginalized individuals toward their surroundings. The value of this term for me is not to romanticize transiency or mobility, or even the appropriation of space, but rather the way tactics reveal specific needs, desires, and activities that are otherwise unavailable within communities. When contextualized by the historical and spatial specificity of regional rhetorics, tactics allow us to become sensitive to area-based practices and critiques that may form the basis of emergent social and political relationships. Indeed mapping the scaled intersectional joints of places and practices composing the regional rhetorics of Juneau ultimately demonstrated a performative mode of political subject formation precisely by understanding this process as one that involves its own strategies and tactics.

Sarah Elwood and Katharyne Mitchell have retooled tactics for educational purposes within the context of popular forms of volunteered geographic information, or VGI. By democratizing access to mapping practices, VGI dramatically differs from traditional cartography in that it emphasizes augmenting conventional forms of geographic information with the knowledge of citizen-driven data collection.57 The growing availability of cheap and free positioning devices, fine resolution imagery, and mapping software enable the ability to create maps that reflect personal and temporary needs, in contrast to the strategic purposes of traditional cartography. Elwood and Mitchell identify “visual spatial tactics” as digital practices that rework the spatial norms of a cartographic interface and the restrictions of strategic place-making.58 Given the development of neogeography as an arena of emergent place-based digital practice, I want to contribute to the critical potential of visual spatial tactics by discussing how my students situate knowledge production arising from the circulating discourses that define the production and reproduction of cruise ship tourism in southeast Alaska.59 In turn, these visual spatial tactics enable us to identify how critical engagements with hegemonic spatial strategies within a region elicits political and educational formation.

Many of my students grew up in Juneau or Alaska and are familiar with the cruise industry because of summer jobs trail guiding on glaciers or leading animal-based excursions such as whale-watching or fly fishing.60 They are primarily working and middle-class young adults who enroll with the intention of obtaining a BA or BS degree, thereby gaining an employment advantage in a tourism, park service, or government position throughout the state. Their initial perception of the cruise industry, like many, was positive in that cruises offer much-needed employment opportunities that would otherwise be unavailable. One student’s recollection of the collapsed timber industry in the 1990s informs the way in which tourism is understood as a means of survival for many in the state:

I can vividly remember the timber industry vanishing, almost overnight in some places. Many people lost their jobs, homes were repossessed, people moved out of the region by the thousands, and there was this angry fog that settled in most of the communities. The dark presence is still felt in some places. This was the transition time between timber and tourism, marking the end of one era and the beginning of another. I am relieved that tourism has created a way for the region’s people to make a living and provide for their families. People have to eat and bills need to be paid. Tourism has filled this need in many places.61

Given the recent intensity with which the Alaskan state has committed itself to increase the size and number of ships, as well as my students’ own obligatory position vis-à-vis the industry, our initial goal was simply to conduct research that would identify how these ships produce space in southeast Alaska. In the first five weeks of the semester, we read cultural and historical analyses of representations of Alaska and then students turned to research cruise ships in the library and in the city. We visited state archives and city museums, collected newspaper reports and policy regulations, conducted personal interviews with local tour guide companies, shop owners, and government officials, and researched scholarship on the cruise ship industry. This work was not meant to be exhaustive, but to initiate a collection of materials relevant to the industry in hopes of engaging the public in dialogue on the state’s recent total commitment to cruise ship tourism. In addition, students focused only on subjects that were of personal interest and, after our initial readings, we identified five categories of analysis: economics, environment, landscape, history, and indigeneity.

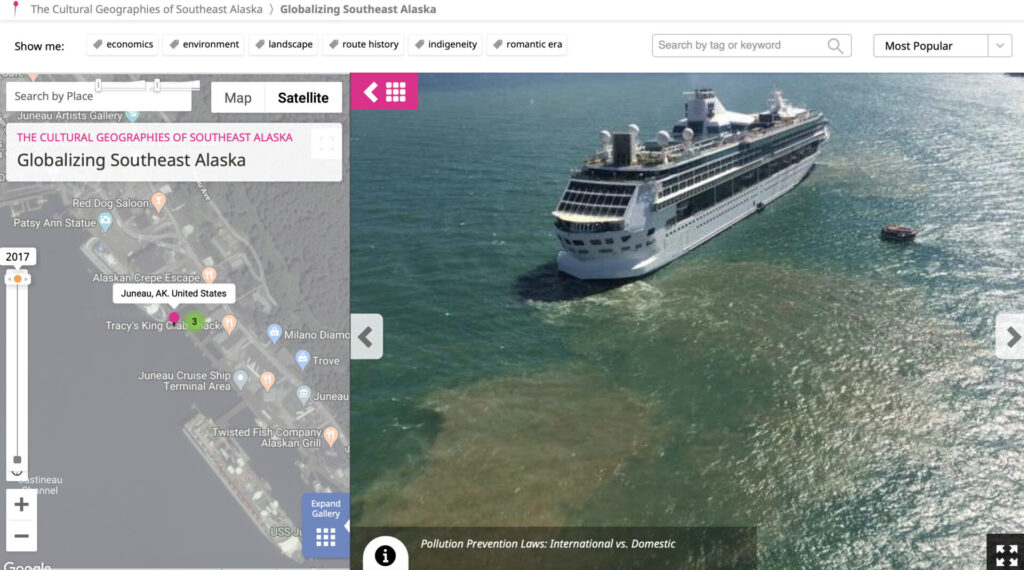

To map how the cruise ship industry impacts southeast Alaska in terms of these categories, we used the online geomedia platform Historypin. This website allows users to “pin” images, texts, and video onto latitudinal and longitudinal sites of a shared interactive map. Each pin can also be placed within a particular year as the map contains a toggle that allows users to view locations within particular time periods. Setting the timeline from 1990–1995, for example, will display pins of events occurring within that temporal window. The map also zooms from a street view out to a continental view of the world, again altering the pins on display according to movements of the map scale (see Figure 4).

The act of pinning thus involves acknowledgment of the spatial and temporal context in which each pin’s content, events, and practices are modified or come into being (see Figure 5).

In this project, pinning constitutes a visual spatial tactic in that students articulate the processes and experiences that are often invisible, unknown, or disregarded in dominant representations and narratives about Alaska. We emphasized collaborative authorship by having students utilize one sign-in name, which gave an aesthetic uniformity to the pins and provided a way to signal the baseline research of this student collective to future authors who may add to the project over time. I understand this project’s use of Historypin as a form of neogeographic praxis in that it constitutes a social form of mapmaking as well as in the way students interacted with one another’s mapping process. By collaborating to write the regional rhetorics of southeast Alaska, they became aware of how the everydayness of the cruise ship industry shapes their own perceptions and beliefs as well as how social, economic, and cultural inequalities are embedded in the landscape. These insights are fundamental to the formation of political subjects, as students came to perceive their lives as part of a larger collective process of global capital, recognized how social and spatial inequalities produced aspects of their own identities and how these identities, in turn, reproduced themselves through their own everyday practices within the landscape.

In effect, this collaborative approach to map-making allowed students to assemble and create an understanding of the region and themselves within it. Students began to discern patterns based on their shared findings and this provoked new conceptions of the city precisely by understanding the multiple ways the cruise ship industry plays a determining role in the regionalization of their community.62 For example, in the process of mapping stores that are owned by cruise lines, one student noted the way in which the ships literally compose the form and logistics of urban space. Students learned that the cruise-owned souvenir stores are strategically located in the immediate shopping district that tourists encounter after deboarding:

Because these businesses are on the front lines of South Franklin street, they spark the initial interest of buyers and receive the majority of the profits the tourist is willing to spend. The cruise lines themselves tailor maps to exclude many local, year round businesses and promote those businesses that they own.63

This detection of the spatial advantage of corporate ownership along South Franklin street then resonated in stark opposition to the concurrent “no camping” ordinance instituted over the same area by the city government. The new downtown marina now emerges as a literal extension of the space of the cruise ships as this ordinance effectively insulates the street from the local poor who are criminalized for attempting to use public space for survival tactics. Students identified this urban strategy again in a lawsuit over head tax revenues that Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) filed against the city of Juneau in 2016. CLIA claims that the construction of the new coastal Seawalk bears little or no relation to serving passengers or crew and therefore violates an eighteenth-century tonnage and commerce clause prohibiting states from taxing vessels in port.64 Here, a multinational corporation seeks to challenge the constitutionality of the tax in hopes of setting a precedent for eliminating those levied in other municipalities. The lawsuit reiterates the battle over urban space usage, and students identify the spatial and historical patterns of political opposition at work through the landscape. Another student writes,

For decades, large multinational corporations have been fighting the state of Alaska to get more freedom without having to pay. Oil companies, mining companies, logging companies, and now cruise lines are fighting to pay less for their presence in the state.65

Through the scenographic practice of researching, composing, and geolocating discursive and material events layered within the composition of pins in and around South Franklin street, students conjoin ways in which multinational capital not only occupies prime territory downtown, but also leverages laws and policies to avoid paying for urban development it deems unsuitable to its own benefit. A historical and spatial pattern recognition emerges embedded in the landscape through the process of collaboratively pinning onto the map, demonstrating how visual spatial tactics teach students to recognize this landscape as a political site of struggle. In this example, the visual accumulation of pins juxtaposing the designated cruise-owned stores, the no-camping ordinance, and the CLIA lawsuit illustrates how regional identity is contingent upon tensions that reproduce advantages for multinationals. Student recognition of the embedded historical recurrence of companies “fighting . . . to get more freedom without having to pay” exemplifies the form of politics that emerge through visual spatial tactics.

Recognizing these oppositional tensions at work across this region involves a second visual spatial tactic, one that challenges modes of inquiry that separate urban space from global processes. A New York Times article reported that Princess Cruises pleaded guilty to illegally dumping oil waste, bilge, and grey water into the ocean from 2005 to 2013.66 One student wanted to incorporate this article onto our map; however such pollution practices do not lend themselves to isolating one location. The site is impossible to ascertain as the impact of the practice transcends spatial-temporal specificity and thus immediately engages the question of scale discussed above. This pin functioned therefore to mark another constructive joint of oppositional forces within the project and within southeast Alaska, in that, being neither inherently local or global, the student’s dilemma about where exactly to locate the pin registers the way in which it forces a break from choosing one of those two isolated modes of inquiry. Cruise ship activity at once pollutes across multiple oceans, including the ecosystem of Alaskan waters, and pumps damaging quantities of noxious nitrous dioxide into the atmosphere over extended durations of time.67 The student decided to pin the analysis of the report into the Juneau harbor (see Figure 6).

Here the student circumvents the geographic constraints of the map and brings within the space of the local these otherwise non-representational temporally-distributed practices. This polemical expansion of the harbor to include global violations extends the cartographic boundary of the local grid to incorporate the pollution of Princess Cruises and thereby absorbs this industry into the very composition of the natural environment of the Gastineau channel. In doing so, the student uses the pin as a visual spatial tactic to articulate the resistant act of extending the local to subsume the global environmental impact of multinational capital.

Perceiving such non-representational spatial impacts on the city also involved extending the temporality of pollution upon the region. Regarding this pin, the student explains the excessive and unseen duration of the presence of the ships by synthesizing several issues that arose in their research on cruise ship pollution:

The pollution will come full circle, it won’t just be some far off polar bear starving to death on a melting iceberg, it will be our coastline real estate washing away in the ocean or our Alaskan salmon populations poisoning our communities. Other industries such as commercial fishing operations and glacier tourism will cease to exist if cruise ship tourism continues at the rate it is going. Pollution creates human health issues like hormonal and reproductive problems, nervous system damage, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s and heart disease. . . . All of this in the name of what? It is clearly not a sustainable endeavor. There will be no pristine oceans or mountains for cruise ship tourists to gaze upon. Cruise ship tourism will implode from the inevitable degradation of the driving force of its income, the environment.68

In exhibiting this contradiction of capital through its environmental impact on southeast Alaska, this mapping is no longer one of an enclosed, static, interiorized, and isolated wilderness that we find in the survival tropes about Alaska. Instead regional rhetorics are deployed to define a practiced place composed of intersecting systems of knowledge, conjoining the material landscape to non-representational, and often effaced, spatial and temporal forces of the multinational cruise ship industry. Traditional cartographic practices and colonial relations between nature and culture, environment and economy, time and space are disrupted by mapping the city as a place undergirded by multinational industrial processes.

Placing pins as discursive joints of opposing forces throughout the map leads to my third example of visual spatial tactics as students posed critical questions about these current socio-spatial strategies with the intent of imagining an entirely different social arrangement. Students’ frustration at identifying the way these industries are detrimental to the future of their region and its people became a foundation for critique, and they began articulating questions regarding what can be done and how:

If cruise ships won’t follow laws put in place by state, federal, and international governments then why would they ever listen to small non-profit organization raising a stink about them dumping pollution into the ocean?; How do you maintain a thriving economic industry to be completely sustainable in a cultural and environmentally rich region of the world?; What would happen if we created a more complex narrative than “the last frontier”?69

In formulating such questions, students began to create collective interpretive frameworks of their city. For example, linking environmental pollution, land appropriation, health care issues, and racial and economic inequalities across history generated a critical perspective on the present moment as an extension of historic inequalities within the region. At this point, the negation of the cartographic grid is not simply an ideological stance advocating the local over the global, or place over space, but expresses a new value in its own right, one that establishes a differentiated, regional, colonial history through tactical and tactile construction. Several students reframed these contemporary inequalities in terms that they originally thought to be part of Alaska’s past. One reflected,

What I found the most shocking from this group’s research is how cruise ship tourism is a form of neocolonialism that is exploiting communities it benefits from. It is not just degrading the environment around it but also the cultures of these communities and rewriting the narrative or history of the places to benefit the stereotypical assumptions created by outside forces like tourists. . . . Through this project I began to understand how effective tourism was in altering, rewriting, and hiding this history.70

Another student writes, “ironically on the heels of the end of classic colonialism, we see the rise of international commerce and the birth of what we now call globalism.”71 Thus, as students pinned the various means in which ecological and geopolitical changes are brought on by the cruise ships, each citation or siting was juxtaposed and therefore spatially linked to nearby pins addressing other historical occurrences such as the displacement of villages and land dispossession in Alaska’s colonial era. Students expressed concern about the long-term impacts of environmental exploitation, and the ecological changes brought by the cruise ships emerged as indissociable from its colonial environments and memories, as the mapping process forcefully aligned these material and ideological continuities embedded in the region and challenged any desire to bracket the ongoing process of colonization out from the urgencies of climate change and economic sovereignty. The visual spatial tactic of shared knowledge collaborations revealed how historic, social, and spatial processes manifest themselves in contemporary forms, and the colonial legacy of Alaska became an active collective interpretive frame that enabled a critical regional history to make its presence felt. The production of the map became a fulcrum in which oppositional forces constructed a location in which an extended space and extended temporality marked a newly differentiated “neocolonial” region for students.

Synesthetic use of places on the map illustrates one last kind of visual spatial tactic. Students began placing pins regarding cruise ship industry practices—such as promotional brochures, state legislation, and public policy—at the site of the Federal Building, and this became the location with the largest number of pins (see Figure 7).72

In this usage we find a cartographic spatial swelling or amplification of meaning, so much so that this space on the map is assigned figurative meaning. The federal building located at 700 Post Street functions for this group of students as a synecdoche of the nation-state. The students’ need to tactically create such a space teaches users to become aware of the significance of this location and directs users’ attention to this site on the map. Students inscribe this location with a figural quality to emphasize the state’s active role in fortifying multinational capital onto the Juneau landscape, prioritizing cruise ship development over social services in southeast Alaska, as if employment were the only necessity for life. By collectively engaging in this figural practice, students shift senses in which they make meaning with the digital map by utilizing the interface’s representation of a literal location (700 Post Street) now as a figural representation of the nation-state. The students direct attention away from its meaning as a static signifier and instead utilize synecdoche to designate the impact of the convergence of nation-state polity with the interests of multinational capital, and in doing so, create their own map of meaning for a receiving audience. If measured against the imperatives of cartographic convention, this figural practice risks being identified as incorrectly placing pins that should perhaps be located in Washington D.C. However, by attending to these pins as a visual spatial tactic, that is by noting the authors’ intention to conjoin state and corporate practices and to use visual objects to alert users of this particular alignment, we become aware of the way this particular group of students’ collaborative regional map-making reveals their own pedagogic practice which would otherwise be ignored, unnoticed, or deemed inaccurate.73 It is important to note that these students are well aware of the decisions of the state legislature on the survival of their university, ferry system, and state resources in general, and therefore locating pins addressing the commercialization of the landscape onto the federal building exemplifies a cartographic modification that recombines multi-scaled regional rhetorics of Juneau through a synecdochic practice that emphasizes the material and social consequences of neoliberal state policies. In doing so, southeast Alaska doesn’t simply appear, but the past, present, and future is creatively and critically experienced by students as though for the first time.

The Production of Space as a Pedagogic Practice

The regional rhetoric of survival in the wilderness took on renewed meaning within the collaborative space of the Globalizing Southeast Alaska course. Students began to view the urban environment as an arena of contestation in which competing social forces and interests—from transnational firms, developers, state and federal government to workers, businesses, and the homeless—all struggle over urban design, land use, and public space. My students utilized visual spatial tactics to produce a social analysis of southeast Alaska and then exhibited this analysis in public. The final project exists as an ongoing public discourse that can be accessed by anyone and remains open for collaboration and feedback from the community and the world.74 By doing so, they created a form of vernacular criticism through which they began to understand themselves as political subjects who collectively mobilized to develop shared knowledge capable of generating critical insights and interpretive frameworks about their surroundings and their place in the world. Yet visual spatial tactics emerge here not simply from collaborating with each other, but rather from the site-specific way students engage the interactive functions of producing a spatial history of southeast Alaska. As such, they identify how learning involves an enactment, a performance, and an embodiment over and beyond cognitive reflection. In addition to facilitating an interactive space in which individuals can foster collaborative frameworks of shared knowledge and critical insights that mobilize politicized subjectivities, visual spatial tactics contribute to the formation of a critical regionalist pedagogy capable of conjoining the regional rhetorics of space with the contemporary processes of interurban globalization typified by the cruise ship city.75

Critical regionalism’s strength lies in reopening and transfiguring this relationship between the differentiated experiences of a particular place and the standardizations and placeless-making forces of corporate hegemony in such a way that outsmarts the latter and uses tactile, tactical, and technological production as a means to unveil the site itself, including its particular ideological and material practices. In a final reflection paper, one student indicates this process by identifying the cruise ship as the primary pedagogue of southeast Alaska:

I have learned a lot about myself from this project. This has really opened my eyes to the place in which I have lived my whole life. I have accessed new connections and understandings about indigenous peoples, economics, politics, and ecosystems here in my hometown. Ironically, the cruise tourism industry has made this interconnectedness very apparent and noticeable in my life and surroundings.76

To grasp the cruise ship industry as a producer of both urban space and self-identity enables a relational theory of the cruise ship city that is both specific and generalizable, located and dislocated, material and discursive. Indeed, the allegorical structure of critical regionalism permits each enactment to mobilize practices away from where its effects are felt, to be honed, appropriated, and reorganized accordingly. Any geopolitical potential of a critical regionalist pedagogy as a progressive aesthetic toward building spaces that permit us to teach and learn—a challenge now confronting all cruise ship cities that hope to avoid acts of survival from determining their own discursive and material spaces—relies on this varied adoption and translation into other local, social, and cultural practices aimed at securing a relational sense of autonomy in an era in which global industries make “interconnectedness very apparent and noticeable.” As a contribution to advancing critical regionalism as a pedagogical practice, Globalizing Southeast Alaska contains the possibility of expanding its political efficacy through its coordinated development in conjunction with the regional rhetorics of other cruise ship cities around the world as well as other neoliberal forms of urbanization.

In response to the call for “the right to nature” that emerged in the 1960s as a result of the perceived development of widespread alienating urban spaces, Henri Lefebvre instead demanded “the right to the city” as the reinvention of urbanization as a scientific, social, and artistic practice capable of producing identity and collectivity as a revolutionary humanist practice. Given the decisive role of knowledge production to contemporary globalized urbanization it becomes vital to not only identify a critical regionalist pedagogy that engages the production of space, but to grasp the production of space itself as a pedagogical practice. How exactly is your region produced—discursively, materially, emotionally—and how does this particular formation order the perceptions, desires, and energies from which you have no option but to learn?

Notes

- Karen Schwartz, “As Global Warming Thaws Northwest Passage, a Cruise Sees Opportunity,” New York Times, July 6, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/10/travel/arctic-cruise-northwest-passage-greenpeace.html. ↩

- Research has emerged in “climate tourism,” “doom tourism,” and “last chance tourism,” which Lemelin identifies as terms that broaden the field of dark tourism to include travel experiences motivated by the desire to encounter the death or extinction of non-human or nature-based tragedies of the anthropocene. See Harvey Lemelin et al., “Last Chance Tourism: the boom, doom, and gloom of visiting vanishing destinations,” Current Issues in Tourism 13, no. 4 (September 2010): 477–493. On dark tourism see, J. J. Lennon and M. Foley, Dark Tourism (New York: Continuum, 2000). On extinction tourism, see Michael Byers, “Arctic Cruises: Fun for Tourists, Bad for the Environment,” Globe and Mail, April 18, 2016, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/arctic-cruises-great-for-tourists-bad-for-the-environment/article29648307/. In June of 2019, Transport and Environment released a report showing that nitrogen oxide emissions from cruise ships in Europe was equivalent to only 15 percent of that emitted by all of Europe’s automobiles in one year. “One Corporation to Pollute them All: Luxury Cruise Emissions in Europe,” Transport and Environment, June 2019, https://www.transportenvironment.org/publications/one-corporation-pollute-them-all. ↩

- The Crystal Serenity offers a $600 shore excursion package to passengers entitled “Study in Global Warming” that includes a 250-mile round-trip flight to Shishmaref, Alaska, a village of 580 that is being lost to rising sea levels. The term critical pedagogy is first used in Henry Giroux’s 1983 essay “Theory and Resistance in Education”; however, the practice emerges from a long historical legacy of educational movements that aspired to link classroom practices to democratic principles of society and specifically to the interest of oppressed communities. For an account of the particularly American tradition of critical pedagogy and its key figures see Maxine Greene, “In Search of a Critical Pedagogy,” Harvard Education Review 56, no. 4 (November 1986): 427–441. ↩

- Crystal Global Public Relations, Crystal Cruises, Crystal Cruises’ Service and Onboard Enrichment Win in Porthole’s Readers’ Choice Awards, Press Release, November 18, 2019, https://mediacenter.crystalcruises.com/crystal-cruises-service-and-onboard-enrichment-win-in-portholes-readers-choice-awards/. The Cruise Web, Crystal Cruises Onboard Activities, accessed June 2020, https://cruiseweb.com/cruise-lines/crystal-ocean-cruises/experience-onboard-activities. ↩

- Tom Stieghorst, “Forging Fulfillment,” Travel Weekly, November 5, 2018, https://www.travelweekly.com/Cruise-Travel/Forging-fulfillment-Cruise-lines-bolster-enrichment-programs#article. ↩

- Semester At Sea, https://www.semesteratsea.org. ↩

- Bob Jessop, “Cultural Political Economy, the Knowledge-Based Economy, and the State,” in The Technology Economy, ed. Andrew Barry and Don Slater (London: Routledge, 2005); Manuel Castells, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture Volume 1: The Rise of the Network Society (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1996); Enrico Deiaco, Alan Hughes, and Maureen McKelvey, “Universities as Strategic Anchors in the Knowledge Economy,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 36, no. 3 (May 2012): 525–541. ↩

- On democracy’s reliance on affordable and accessible education see Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015). The dismantling of the public university is the subject of much academic energy. See Christopher Newfield, Unmaking the Public University: The Forty Year Assault on the Middle Class (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008); Colleen Nye, Christopher Newfield, and James Vernon, eds., “The Humanities and the Crisis of The Public University,” special issue, Representations 116, no. 1 (2011); Christopher Newfield, The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 2018). ↩

- Christopher Newfield’s dialectic approach to the mid-century American university’s institutionalization of humanism situates its practice as a historically specific theory of professional middle-class possibilities in the era of industrialization. This structural analysis of humanism within post-war academic and industrial settings thereby presents the significant political rediscovery that alongside its conservative legacy, liberal humanism also preserved within itself radical standards for developing human potential which at times, “persisted, and still persists, to unsettle professional and managerial life, often acting as a critical or antagonist position, jostling its institutional superior, the technosciences, while drawing on radical and noncapitalist traditions.” Christopher Newfield, Ivy and Industry: Business and the Making of the American University, 1880-1980 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 47. On “racial liberalism,” which frames antiracial discourse as an organizing strategy for US capitalist hegemony following the war and enables institutions like the American university to idealize, imagine, and anticipate but never achieve their espoused egalitarian and liberal values see, Jodi Melamed, Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). ↩

- In the process, public universities increased part-time academic labor, online instruction, and reduced general education requirements, subsequently cheapening costs, purging liberal arts curriculums, and weakening faculty governance. Neoliberalism describes a governing rationale capable of disseminating market values to all spheres of human life. Its economic features include the liberalization of government restrictions on market competition, weakening of the welfare state, and consolidation of flexible, specialized models of production, industrial organization and inter-firm relations regionally disseminated to intensify the globalization of capital. See David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1990); Aiwa Ong, Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logic of Transnationality (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999). ↩

- On biometric organizational studies, see Taemie Kim et al, “Sociometric Badges: Using Sensor Technology to Capture New Forms of Collaboration” Journal of Organizational Behavior 33 (2012): 412–427; On quantified selves see Deborah Lupton, The Quantified Self (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016); On smart cities see, Ayona Datta and Nancy Odendaal, “Smart Cities and the Banality of Power” Society and Space 37, no. 3 (2017): 387–392; On parametric urbanism, see Patrik Schumacher, ed., Parametricism 2.0: Rethinking Architecture’s Agenda for the 21st Century (London: Wiley, 2016). On the historical rise of the university as an anchor for state-sponsored regional economic development, see Margaret O’Mara, Cities of Knowledge (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); Enrico Delaco, Alan Hughes, and Maureen McKelvey, “Universities as Strategic Actors in the Knowledge Economy” Cambridge Journal of Economics 36, no. 3 (2012): 525–541. ↩

- Simonetta Armondi and Stefano Di Vita, ed., New Urban Geographies of the Creative and Knowledge Economies: Foregrounding Innovative Productions, Workplaces and Public Policies in Contemporary Cities (London: Routledge 2018); Casey M Lindberg et al., “Effects of Office Workstation Type on Physical Activity and Stress.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 75, no. 10 (2018). ↩

- Annalee Saxenian, Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996). On the unique urban forms arising from the cultural “deterritorialization” of land and earth through speculation and finance capital, see Fredric Jameson, “Culture and Finance Capital” The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998 (London: Verso, 1998). ↩

- Here I follow Katharyne Mitchell’s assertion that globalization and neoliberalism have placed “new pressures on the state from scales without and within the nation, and thus the education of national citizens in connection with both state formation and political economy, must now be considered within this global framework.” Katharyne Mitchell, “Educating the National Citizen in Neoliberal Times: From the Multicultural Self to the Strategic Cosmopolitan.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 28, no. 4 (December 2003): 391. ↩

- I use the term cruise ship city to refer to the set of spatial practices in which a local population is annually outnumbered by seasonal tourists via cruise ship ports-of-call, resulting in the development of urban environments built specifically to accommodate this transient population for entertainment, educational, and economic purposes. Current examples include Venice, Cozumel, and the Caribbean islands. For a recent documentary on the social impact of cruise ships on urban space see The Venice Syndrome. dir. Andreas Pichler (2012). ↩

- Lefebvre emphasizes the significance of this point further in The Production of Space: “A revolution that does not produce a new space has not realized its full potential; indeed it has failed in that it has not changed life itself, but has merely changed ideological superstructures, institutions or political apparatuses.” Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1991), 54. ↩

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 50. Cognitive mapping is of course one of many pedagogical tools proposed by Jameson. Fredric Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. Carey Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (University of Illinois Press, 1990), 347–360. ↩

- Doreen Massey, “Power-Geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place,” in Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures, Global Change, ed. Jon Bird et al. (London: Routledge, 1993). ↩

- Neil Smith shows that the category of scale is not simply to identify the ideas at work within a particular level of analysis, nor even the lateral relations between the body, home, community, city, region, nation, and globe, but rather how interpretations of scale function to shape and constitute each other. See Neil Smith, “Homeless/Global: Scaling Places,” in Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures/Global Change, ed. John Bird, Barry Curtis, George Robertson, and Lisa Tucker (New York: Routledge, 1993). ↩

- See for example, Neil Campbell, “Critical Regionalism, Thirdspace, and John Brinckerhoff Jackson’s Western Cultural Landscapes” in Postwestern Cultures: Literature, Theory, and Space, ed. Susan Kollin (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007); Rachel C. Jackson, “Locating Oklahoma: Critical Regionalism and Tranrhetorical Analysis in the Composition Classroom” CCC 66, no. 2 (December 2014), 301–326; Douglas Reichert Powell, Critical Regionalism: Connecting Politics and Culture in the American Landscape (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007). ↩

- Barbara Allen, “On Performative Regionalism,” in Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition, ed. Vincent B. Canizaro (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007). ↩

- Allen, “On Performative Regionalism,” 421. ↩

- Ananya Roy, “The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory,” Regional Studies, 43, no. 6 (July 2009): 820. ↩

- The term critical regionalism is introduced in Alex Tzonis and Liliane Lefaivre, “The Grid and the Pathway. An Introduction to the Work of Dimitris and Suzana Antonakakis,” Architecture in Greece (Athens, 1981), 15. Jameson’s discussion in The Seeds of Time addresses Kenneth Frampton’s argument in ‘‘Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (New York: The New Press, 1998), 17–34; Fredric Jameson, The Seeds of Time (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 129–205. ↩

- In its celebration of the provincial, neoregionalism imagines itself opposed to the homogenizing sterility of corporate gentrification processes. Ursula K. Heise traces the origin of this intensification of libidinal and political investment in the local as a site of resistance to the 1960s, where autonomy and self-sufficiency were championed as a political commitment to one place, while mobility and nomadism were rejected as the deterritorializing practices of “large-scale, abstract, and often invisible networks of authority, expertise, and exchange that structure modern societies.” Ursula K. Heise, Sense of Place, Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 2008), 31–38. ↩

- Frampton, “Towards,” 27. ↩

- Jameson, Seeds, 195–200. ↩

- Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979). Edward Said identifies imaginative geographies as those that arise from a poetic process whereby seemingly vacant and anonymous reaches of distant space acquire emotional and rational meaning. ↩

- Jason J. Moore, “The Capitalocene, Part I: On the Nature and Origins of Our Ecological Crisis.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44, no. 3 (March 2017), 594–630. ↩

- On the necessity to broaden theories of urbanization beyond developmental models, see Jennifer Robinson, Ordinary Cities: Modernity and Development (London: Routledge, 2006). ↩

- Cruise Lines International Association reported 27.8 million passengers in 2019 and an annual revenue of 41.6 billion dollars. The global estimation is on average 1.36 million new passengers every year. In Alaska, for the third year in a row from 2016 to 2019, the number of passengers set a new record with 1,233,735 passengers. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, CLIA forecasted an increase of 7.4% for the 2020 season. (“2020 Cruise Trends and Industry Outlook,” Cruise Lines International Association, 2020). Only three Alaskan cities have a population over 10,000. ↩

- Southeast Conference Board, “Southeast Alaska by the Numbers 2019”, 6, http://www.seconference.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20Southeast%20by%20the%20Numbers%202019.pdf ↩

- State report on the economic impact of cruise ships, 2017: https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/ded/DEV/TourismDevelopment/TourismResearch.aspx; “Promoting Alaska and Upgraded Infrastructure Needed for Continued Industry Growth,” Cruise Lines International Association Alaska, https://akcruise.org/about-clia-alaska/current-issues/.; City and Borough of Juneau website on the Cruise Ship Terminal Project, http://www.juneau.org/harbors/documents/DocksHarborscruiseterminalbrochure.pdf. ↩

- Jacob Resneck, “Juneau’s downtown cruise terminal preparing for bigger boats,” KTOO, January 27, 2017, https://www.ktoo.org/2017/01/26/juneaus-downtown-cruise-terminal-preparing-bigger-boats/; “Seawalk set to open this month,” Juneau Empire, May 8, 2017, https://www.juneauempire.com/news/seawalk-set-to-open-this-month/. ↩

- “CLIA 2019 North American Market Report,” https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/2019-year-end/2019-north-american-market-report.ashx. This is a 20 percent increase from 2018, up from a 14 percent increase the previous year. ↩

- Eighty-five percent of Alaska’s state budget comes from oil revenue. Alaska Oil and Gas Association, State Revenue Figures, 2011–2015, https://www.aoga.org/state-revenue/. ↩