[T]he boat is a floating piece of space . . . that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea . . . . The ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.

––Michel Foucault1

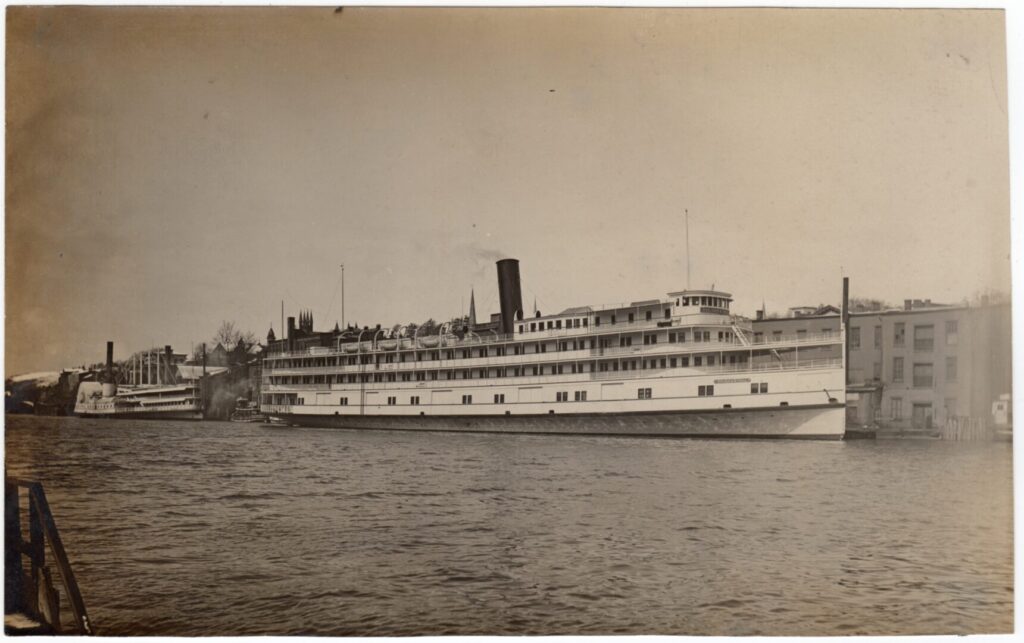

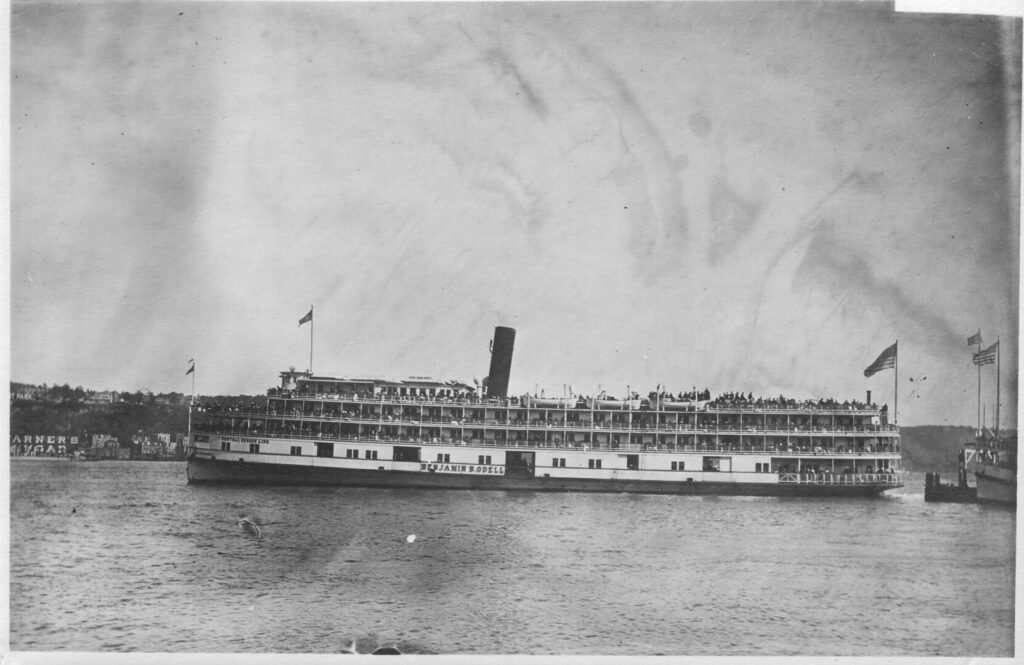

Around six o’clock in the evening on July 27, 1919, an undercover investigator boarded the Hudson River Steamboat Company’s palatial steamer, the Benjamin B. Odell, in Newburgh, New York.2 As the Odell cruised down the Hudson River towards her destination, Manhattan’s Franklin Street Pier 24, the investigator collected information regarding social relations aboard the steamer––anything that might be of interest to his employers, the members of New York City’s Committee of Fourteen (COF, 1905–1932), a powerful, privately-funded police reform and anti-vice organization. He observed the crowd of some three-thousand working-class pleasure-seekers, watching how they danced and interacted with one another in the Odell’s saloon and on the dining and observation decks, and noting the behavior of the boat’s musicians. He looked on as couples used her private staterooms for short intervals for apparently “immoral” purposes. He pumped the Odell’s crew for information, hoping to gain insights into the character of the vessel’s typical passengers and to suss out any suspicious or illegal activities. And he succeeded in “picking up” two wage-earning women, both of whom were employed in Manhattan that summer. When the Odell reached its final stop, he disembarked with one of the women, who enlisted his help in procuring liquor illegally (since enforcement of wartime prohibition, which banned the production and sale of intoxicating beverages, had commenced on July 1) and invited him to surreptitiously visit her in her room at the Cambridge Hotel in Brooklyn.

This article considers the undercover investigator’s written account of his experiences, reckonings, and observations aboard the crowded Odell that night in late July 1919. A close reading of the report enriches our understanding of the practices of courtship and pleasure-seeking that punctuated the heterosocial, segregated spaces of working-class leisure and amusement in and around New York City during America’s “Red Summer.”3

The investigator’s written account offers vital opportunities to examine how wage-earning women and adolescent girls carved out channels for attaining individual freedoms, love, companionship, and gratification in their leisure hours via weekend steamboat excursions on the Hudson, and how Progressive reformers monitored their activities in the hopes of securing new avenues of social control and bolstering systems of social protection. Consideration of the report reveals that the relatively unsupervised spaces afforded by steamboat excursions appealed to working women and girls partly because they offered access to desirable forms of male companionship and sexual satisfaction, minus many of the risks to reputation and disciplinary consequences that often accompanied the pursuit of such goods on the mainland.4 The fact that steamboat excursions made forms of sexual, romantic, and social autonomy available to wage-earning women and girls (and, sometimes, much to the chagrin of authorities, to sex workers) for the price of a ticket plus rental fees is particularly salient in the context of this report, given wartime prohibition’s onset just four weeks prior and, more broadly, given the intense escalation of efforts by various local, federal, and private authorities to surveil and control public sexuality in general, and “promiscuity” among wage-earning immigrant women and girls in particular, that crystallized in the lead-up to America’s declaration of war in April 1917.5

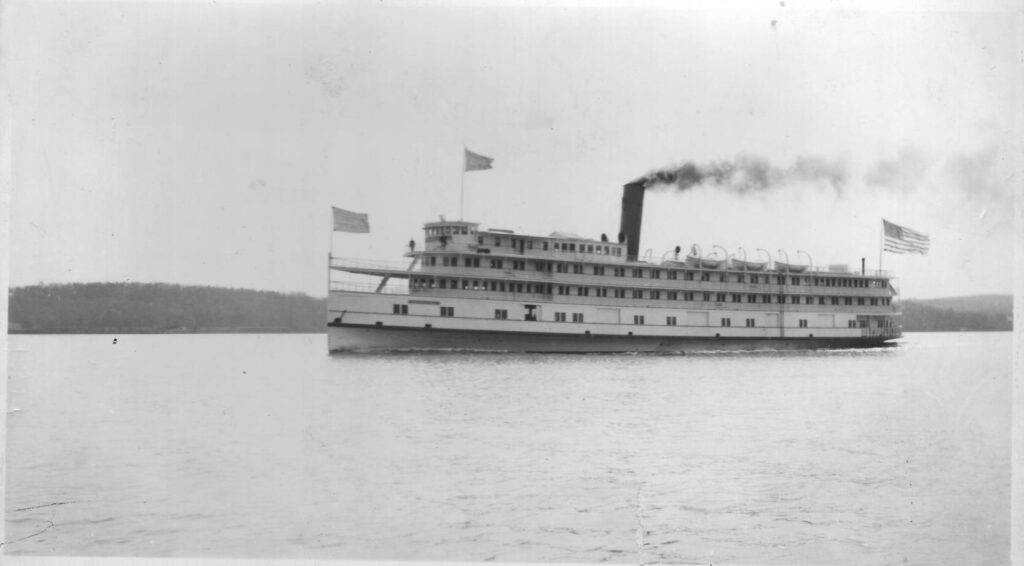

As they became increasingly commercialized around the turn of the century, steamboat excursions offered wage-earning women and girls compelling opportunities for “flirtations and amusement, without the chaperonage of parents.”6 Hudson River steamboats, which since the 1850s had faced increasing competition with trains in the freight and personal transport business, continued to attract passengers in the early twentieth century by providing comfort, well-furnished private staterooms, and top-notch entertainment options. They were fitted with fine furniture, dining rooms, live music, spacious observation decks, and dance floors. Yet the price of fare remained low enough that most visitors and residents could enjoy the experience. An armada of steamboats was devoted solely to excursions, moonlight sails, and charters, and during the hot summer months especially, masses of working people utilized these boats to escape the city heat and visit popular destinations like Bear Mountain, Orange Lake Park, and other beautiful outdoor recreation spaces scattered along the Hudson River.7

Massive, deluxe night steamers like the Benjamin B. Odell of the Central Hudson Line featured luxurious amenities comparable to those found in upscale hotels at the time.8 Their main business was running freight during the week, but they ran special passenger excursions on weekends during the summer months. Working people traveling to and living in New York who could not afford a stay at a mountain hotel or other more elaborate vacation outings could afford a getaway on the Hudson.9

Despite their immense popularity at the time, steamboat excursions have gone underexamined by social historians of the Progressive Era. Accordingly, scholars have also mostly overlooked the steamboat’s unique position within America’s urban recreation landscape during the First World War, along with the many successive attempts by Progressive social reformers both nationally and in New York to track and quell what they judged to be certain “immoral,” “dangerous,” and pestiferous types of social relations and pleasure-seeking afforded by steamboat excursions.

The first section of the article discusses relevant background contextual factors, including the commercialization of urban amusements at the turn of the twentieth century and efforts by Progressive reformers to use undercover investigation to monitor and intervene in social conduct aboard steamboat excursions. A comment on the report’s authorship is provided in the second section. The report is considered in the third section.

I. Amusement Resources for Wage-Earning Women and Girls

A “golden age” of public recreation and commercialized entertainment dawned in America’s cities in the 1890s, just as rapid industrialization and urbanization were restructuring everyday experiences of and assumptions about work and leisure for millions. Urban wage-earners, including a growing number of women and adolescents, sought a “necessary release from their increasingly regimented lives” in the realm of commercialized recreation.10 The widening array of working-class amusements offered workers subsumed under capital “a refuge from the dominant value system of competitive individualism.”11 Wage-earners forged a pseudo-autonomous domain where a degree of choice and/or agency was attainable at the level of the individual, and where distinct “alternative” (if not “oppositional”) working-class cultural practices and values could be fashioned into bulwarks against the despotic, disciplinary pressures of their working lives.12

In the expanding territory of commodified heterosocial amusement, wage-earning women and girls in their leisure time “experimented with new cultural forms that articulated gender in terms of sexual expressiveness and social interaction with men.”13 Their heightened visibility in public offered many female workers novel forms of “physical and psychological freedom.”14

Yet while wages earned outside the home afforded newfound independence, most young women still lived at home and did not get to retain much if any of their wages.15 A 1910 study concluded that the vast majority of Boston’s wage-earning women and girls lived at home and were expected to contribute “all their earnings to the family purse and receive back only so much as [was] necessary.”16 In 1916, Maude E. Miner, an influential Manhattan probation officer and secretary of the New York Probation and Protective Association, likewise reported that according to one of her Association’s institutional appendages, the Girls’ Protective League, “nearly all the young women living at home . . . gave their entire wage to their families,” with only “some receiving back a small allowance” for carfare, meals, clothes, and/or “a small amount of amusement.”17 Miner, who became a COF member in 1912, emphasized that most working women had to surrender “their unbroken [pay] envelope in return for . . . little more than their board and necessary clothing.” As a result, many were disposed to “seek their amusement in places frequented by dangerous people.”18

The continued prevalence of “treating” throughout the 1920s implies that many working women had cause to barter sexual favors in exchange for a portion of the higher male wage.19 If wage-earning women’s “free” participation in leisure culture was conditioned by their scandalously low wages and lack of spending money, it was also challenged by the dramatic escalation of the assault on female “promiscuity” that unfolded during the war years, culminating in the passage of numerous pieces of draconian legislation and the arrest and indefinite incarceration of thousands of women under the auspices of the so-called “American Plan,” which aspired to staunch the spread of sexually-transmitted infections via unprecedented policing measures.20

The fighting in France had stalled by the summer of 1919. But the moral panic over the spread of “venereal disease,” which emerged during Pershing’s 1916–1917 “Mexico Expedition,” and subsequently exploded in intensity following America’s declaration of war on Germany, lingered on stubbornly. It was stirred to the surface again by the prospect of many thousands of young soldiers, fresh from France and ignorant of city life, passing unsupervised through New York and other metropoles on their way home to various rural locales across America.21 Indeed, according to prominent Progressive reformers, the primary “social hygiene problem” of the war concerned not prostitution, but rather sexual relations between “the individual soldier and individual girl.”22

In the early twentieth century, America’s urban reformers assumed an increasingly unemotional, scientific posture towards crime, vice, and social disorder relative to their antecedents.23 Protecting working women’s right to “clean” recreation became “one element in the comprehensive effort to reconstruct community life and save the family.”24 Progressive urban reformers acknowledged that commercial leisure establishments filled legitimate needs felt by millions of working Americans. As one reformer focused on adolescents and childhood development put it, “After eight hours of activity as a cog in an industrial machine, the greater part of human nature [was] left over and pressing for utilization.” Hence, “the hours of leisure” were “far more significant for life as a whole” for the industrial working class than were “the hours of work.”25 “We must admit to ourselves,” exhorted leading dance hall reform crusader and head of New York’s Committee on Amusement Resources for Working Girls, Belle Lindner Israels, in 1909, that “play is not a luxury, but an absolute necessity to the working world to-day.”26 For Israels (a future COF member), it was natural for the workingwoman to want “to break away from the constraint of her cramped, unemotional life” by seeking pleasure and autonomy in the sphere of cheap and accessible amusements.27

Such pleasures were not free, however. Amusement reformers fretted that, as founding COF member, Greenwich House organizer, and prominent feminist thinker, Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, once explained, “the young men of the big cities” were “not gallantly paying the way of these girls for nothing.” In instances where women and girls were unable to “pay their cost,” “attendant circumstances” could arise, converting “natural channels of joy into debasement” in the process. While “the price” of the exchange might “not be that which leads to despair,” such transactions nevertheless contributed to “a lowering of the finer instinct and a gradual deterioration of” individuals’ “appreciation of personal purity,” thereby hastening the spread of the “social evil.”28

Sunday was seen by some leading recreation reformers as “the day of compensation,” which playground advocate Joseph Lee defined as “the day of fulfillment of those essential purposes of life for which the weekday has left no room,” and the day when “those things that belong to us not as industrial implements” but as civilized, fully realized human beings could be cultivated.29 Reformers recognized that for most women and girls making between five and nine dollars per week, music places, movie theaters, arcades, amusement parks, beaches, and railway or boat excursions, “with their doubtful attractions,” represented the only easily accessible leisure options.30 At the same time, commercialized leisure presented “a growing menace,” a corrupting force driven by morally unscrupulous, profit-hungry pleasure merchants.31 Finding cities without adequate “clean” recreational provision, predatory “private commercial interests” had stepped in to exploit the lacuna “for great financial gain,” utilizing “every possible method . . . to increase profits,” regardless of perceived hazards to workers, consumers, families, social order, and the moral character and physical welfare of the urban population.32 Progressive reformers worried the working girl’s “innocent love of pleasure” was being “transmuted through gradual corrupting relationships into a life of danger” in these commercial leisure spaces, which many parks and amusement activists perceived to lack the requisite levels of supervision by morally credible authorities needed to protect the population from the dangerous influences emanating therefrom.33

Commercialized leisure culture both “fascinated and appalled” a wide gamut of America’s leading Progressive settlement advocates, social scientists, and social workers. Though ideologically diverse, urban reformers broadly agreed that allowing the character of public recreation to be directed by unfettered commercial forces was both to deny wage-earning women a “legitimate outlet for their natural love of pleasure” and to force the working masses to seek restoration from the strain of industrial work life and cramped housing in the morally dangerous forms of gratification offered by these affordable attractions, where moral ends were subordinated to desire for profit-maximization. Because the realm of cheap amusements directly influenced the lives of millions of adults and adolescents, it represented by 1919 an even “more serious challenge to the moral order” than the threat of commercialized prostitution, the most visible and established forms of which had been effectively broken up and scattered to the margins in New York and other large metropoles by the mid-1910s.34 “Private amusement enterprises,” as Israels put it, were “the open door for the social evil.” Exposure to the “wrong kind of recreation,” argued Israels, spawned “disastrous results.”35 The average workingwoman’s “moral vigilance” was steadily “broken down” through exposure to immoral conditions in the amusement establishments accessible to her.36 The combination of “infectious music, the hot room, the exciting contact of her partner and the drink served during the intermission” inevitably induced her to relax her usual standards of conduct and morality until, “hooked by an illusory and perilous “ideal of amusement,” she finally embarked “upon a career of loose living.”37

The “pitfalls” for women, Israels and other recreation reformers believed, “were at their worst in the summertime, when beach resorts, amusement parks, picnic areas and excursion boats all made alcohol easily available,” and where rowdy music and novel dance styles characterized by intimate, cheek-to-cheek contact thrived unchecked.38 For many Progressive turn-of-the-century reformers, “the entire working class appeared as a group of children whose behavior needed to be reshaped and controlled” via undercover surveillance.39 As Elisabeth Perry has argued, leading dance hall reformers and other Progressive amusement activists “had a tendency to patronize,” or in some cases “‘matronize,’ those they wished to help, and to offer only palliatives rather than changes more central to working-class needs.”40 Relatedly, leading urban antiprostitution and anti-vice campaigns of the time found some success in reshaping “urban sociability” and diminishing “the volume and visibility of organized prostitution,” but largely failed to improve the life chances of many wage-earning and immigrant women.41

For wage-earners looking to sidestep the tightened grip of morality regulators over urban amusement spaces, a ride aboard the Odell afforded valuable opportunities for unsupervised entertainment, romance, and casual and transactional sexual commerce. Investigations into public conduct aboard steamboat excursions unfolded in large cities around the country, mostly without the heavy levels of press coverage afforded other similar investigations. Immorality was “a commonplace” on Baltimore’s popular excursion boats and around the shoreside parks and resorts regularly serviced by them.42 In Chicago, alderman George Pretzel reported witnessing “unprintable” sights aboard lake excursion boats. Women were allowed “to solicit openly” on the decks, he said, while the boat’s staterooms were “so busy” with immoral traffic it was “necessary to stand in line and await your turn.” Pretzel charged that many women who had been driven out of the city’s old red-light district by police action over the previous years were now “plying their arts among the passengers on excursion boats.”43 Investigators employed by Chicago’s Juvenile Protective Association, a prominent reform society founded by Jane Addams in 1901, took more than three dozen undercover journeys aboard the large excursion boats on Lake Michigan throughout the early 1910s. They discovered that while the boats seemed to provide “innocent enjoyment with fresh air and the holiday making which city young people so obviously need,” they were in practice “virtually floating houses of vice and a fruitful source of supply for the so-called ‘White Slaver.’”44 The Chicago Vice Commission, the first mayor-appointed urban vice commission of its kind, affirmed these conclusions in its 1911 report, The Social Evil in Chicago. The Commission found that holiday steamers operating in the city’s vicinity transformed into “floating assignation houses” during the summer; staterooms were rented out several times over the course of a three or four hour trip, sometimes by young couples who investigators observed to be lying on berths within in various states of undress.45 Gambling was practiced openly aboard the steamers, liquor was sold to minors, staterooms were rented out indiscriminately without regard for the marital status of couples, over and over again for short intervals during a single trip, and couples were exploiting the dimly lit, unsupervised decks to get physically intimate in ways offensive to reformers’ social hygiene-oriented sensibilities.46 Dancing aboard the lake boats was “vulgar, rough and indecent,” precisely the sort which reformers of the day worried could corrupt the moral character of otherwise innocent young amusement-seekers.47

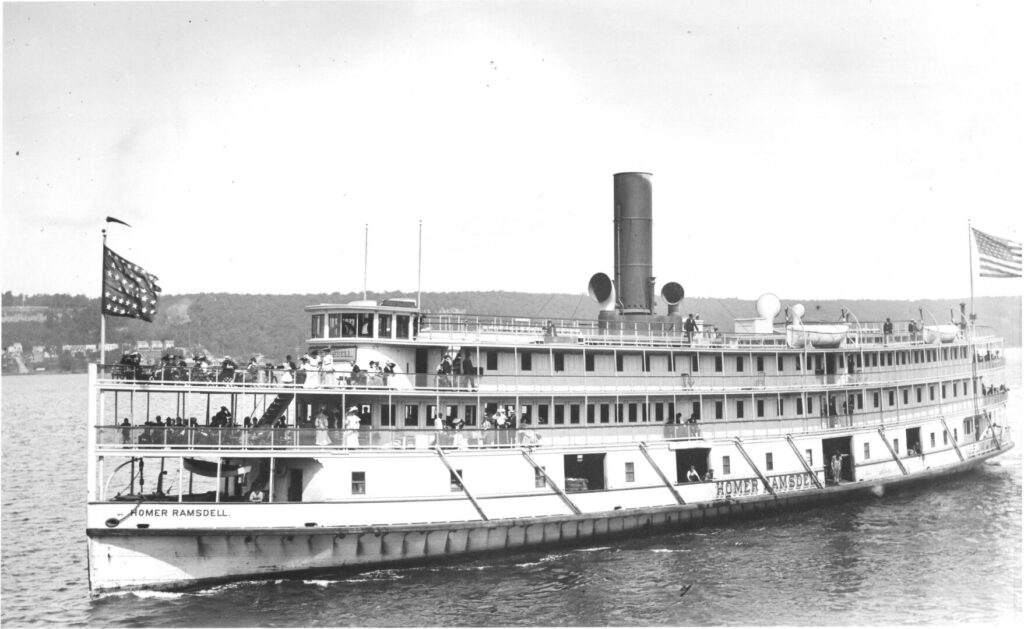

Similar “objectionable” practices of casual and for-profit “immorality” were also observed aboard Hudson River excursion steamers. Writing in 1909, Israels charged that behavior aboard the Central Hudson Line’s Homer Ramsdell was “far worse” than even that observed on the typical Coney Island excursion boats. The worst offenses, said Israels, pivoted on the use of these larger boats’ private staterooms, which were rented liberally to “anybody who [had] the price.”48 According to undercover investigators employed by Israels’s committee, many couples who rented the staterooms aboard the Homer Ramsdell “did not require the use of them all day,” since their purpose in renting them was “not one of rest or comfort.” So they engaged in a secondary speculation, renting them for brief periods. An interview with a ticket seller confirmed that even though all the staterooms had already been booked by the time the boat was underway, a room could nevertheless be acquired for twenty-five cents for the brief interval between the 129th Street stop and the final destination at Franklin Street pier.49 To make matters worse, from the perspective of concerned amusement reformers at least, there were “so many political and other interests” involved in the steamboat excursion trade––indeed, as Israels observed, an ex-governor of New York, Benjamin B. Odell (the namesake of the boat discussed in this essay), controlled the Central Hudson Navigation Company––that the problem of “how to legislate out of existence the bad features of the summer amusement places” appeared insoluble.50

By 1912, Israels’s group was pursuing a two-pronged strategy for opposing steamboat “vice,” namely cooperation with business enterprises and legislative reform.51 It had successfully partnered with eight steamboat lines and convinced the New England Navigation Company to put supervisors on boats to police moral behavior, and was actively attempting to push through federal legislation to address perceived problems related to dimly lit decks, the indiscriminate renting of staterooms, and the general lack of supervision of social conduct.52 Yet three years later reformers were still commenting that aboard the apparently respectable Hudson River steamboat excursions unfolded the “worst evils, including the use of staterooms on day boats for immoral purposes.”53 Styles of dance prohibited in the city, where restrictive dance hall legislation was enforced in the most popular places by a force of hard-nosed inspectors, were flourishing on the unsupervised, crowded dancefloors of Hudson River steamboats, especially those of the colossal, luxurious night boats that ran popular weekend excursions during the summer months.

“Floating Houses of Prostitution”

It was hardly news to the COF in July 1919 that certain “immoral” forms of social conduct could be found aboard the popular steamboat excursions on the Hudson River. Already in 1908, the COF’s chairman, pioneering archaeologist and rector of St. Michael’s Church on West 99th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, Reverend Dr. John P. Peters, wrote that undercover investigations had “shown that some of the steamboat companies, whose officers and directors are quite respectable persons, allow the staterooms on certain of their boats to be let by the hour, or similar periods, evidently for immoral purposes, these boats being in fact floating houses of prostitution.”54

The COF was the most powerful and successful private antiprostitution and police reform organization in New York City during the Progressive Era.55 Funded by wealthy New Yorkers, especially including (beginning in the 1910s) the nation’s chief anti-“white slavery” advocate, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and his Rockefeller Foundation, and consisting of well-connected clergy, sociology-trained social workers, lawyers, social settlement advocates, professors, and various other well-educated and often highly credentialed professionals, the COF worked to alter the “moral geography” of the city from above “by exploiting the mutability of consumer capitalism.”56

The COF’s original goal was a relatively narrow one: to close and/or effectively regulate the notorious so-called “Raines Law hotels.” Like its predecessor organization, the Committee of Fifteen, the COF and its allies emphasized that the moral and/or hereditary unfitness of “weak-willed” individuals was far from the only driver of “the social evil.” They believed that corrupt authorities and apparently respectable business enterprises and property owners who profited either directly or indirectly from forms of “commercialized vice” bore much of the responsibility for the perceived moral decay in America’s cities. The 1896 Raines Law aimed to curb drinking on Sundays by restricting alcohol sales to hotels, but instead inadvertently resulted in the conversion of hundreds of saloons into “badly run” “pseudo-hotels,” complete with bedrooms on the premises, which remained open all night, attracted unwitting tourists, enjoyed police protection, and relied on profits from gambling, prostitution, and other “vices” to offset higher operating costs.57 As its work against the “evil” of the Raines Law hotels progressed, the COF’s leaders came to see the battle against commercialized vice as having more and more ramifications. By the time of the group’s reorganization under a broader mandate in February 1912, its original desire to control “disorderly” saloonkeepers and property owners and break up related business connections had evolved into a more ambitious and far-reaching mission of gaining “control of public amusement” in general across the city.58

The COF pursued a savvy form of interest group politics to defend the “moral character” of the wage-earning population, protecting it from the perceived dangers of “vice” while cultivating new methods of social control and punishment. Its members tended to avoid the “emotional and moral valences” of old-fashioned “rescue work.”59 COF members were by no means always in agreement, but they generally concurred that “repressive laws produced better people and a more moral urban environment suitable for producing people with better ‘character.”60 The COF sought to “break the link between sex and commercialized leisure” and to clean up amusement culture as much as possible in general through surveillance of immigrant and working-class leisure spaces.61 This surveillance enabled COF members to covertly keep tabs on a variety of social actors simultaneously, including commercial workers, property owners, store managers, proprietors, medical professionals, “charity girls,” sexual minorities, police officers, sex workers, middle-class “slummers,” and working-class “toughs.”62

In addition to calling for an end to municipal corruption and for the construction of better, more efficient police and court systems, the COF argued for the “separation of recreation from vice.”63 To achieve this and other goals, staff members trained and commanded a force of amateur undercover investigators, men and women chosen for their ability to blend in or “pass” within various working-class leisure environments and solicit useful information without arousing suspicion. By using the information gathered by its investigators in various ways, the COF “made an end run around the law and the legislature and went straight to the source,” forging cooperative bonds with “insurance companies and liquor dealers, who were already on the offensive against temperance organizations.” In the process, it cultivated a formidable “mode of interest group politics” that accommodated business interests and forced “them to become partners in its (moral) program.”64

The police and the COF initially distrusted one another. But their relations gradually improved. By 1918, the COF was, in Peters’s words, “almost . . . an adjunct of the police force.”65

As Scott W. Stern notes, COF investigators “gambled and drank on the job, and possibly slept with some” of the individuals they were tasked with observing, though such events would be left out of the reports they submitted to their superiors, reports that were regularly passed along to various police authorities cooperating with the COF’s agenda.66 Indeed, undercover vice investigators were problematically tasked with being participants in the very “disorderly” activities they were supposed to report on.67 However, the “mantle of investigator” conveniently elevated them above moral scrutiny, as far as the COF’s leadership was concerned.68

As part of its regular work monitoring commercial amusement spaces, the COF attended to the peculiar forms of “immorality” observed aboard the large steamers servicing the city’s vicinity. In 1916, Maude Miner echoed Israels’s prior observation that steamboats operating between cities in New York and surrounding states were apparently being “utilized for immoral purposes.” “Indecent actions” and “the presence of professional prostitutes,” alleged Miner, had been registered on many such boats, which sported “dimly lighted decks,” and whose staterooms were noted to have been sometimes “occupied several times during a trip of less than twelve hours,” raising suspicions as to the nature of their usage.69 To combat the “moral dangers” facing working girls and women aboard these vessels, Miner argued that steamboat companies should enhance illumination of decks, impose stricter regulation of stateroom rentals, and employ an adequate number of matrons aboard each steamboat to more effectively supervise passengers’ conduct.70

Leaving aside a few scattered public utterances, the COF assumed a policy of no publicity when it came to its surveillance of steamboat companies, which tended to be owned and operated by highly reputable individuals and/or families, preferring instead to use information gathered by investigators in direct, behind-the-scenes negotiations with corporate management.71

II. Note on Authorship

The investigation report discussed in the next part of this article, an eight-page typewritten document housed in the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the New York Public Library, is unsigned, making the identity of the investigator a matter of speculation.72 There are good reasons, I think, to assume the report was penned by David Oppenheim, an experienced Jewish investigator active throughout 1919 whose fluency in Yiddish and German and affinity for fitting in among vastly dissimilar crowds made him a particularly useful investigator for the COF. At eight typewritten pages the report is exceptionally lengthy and contains comprehensive accounts of numerous conversations. This comports with how Oppenheim typically worked. Few investigators attempted such an approach to report writing, probably because it demanded the possession of a remarkably keen memory as investigators did not have access to any portable recording devices.73 Additionally, language used in the unsigned report is like that used in other reports Oppenheim wrote around this time. The two most convincing instances involve the use of the slang phrases “appeared to be game” and “pull off a piece,” which appear both in the report on the Odell and in at least one other report written and signed by Oppenheim within three months of the Odell report’s creation.74 Finally, Oppenheim, who owned a clothing store on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan, possessed remarkable capacities that few other COF investigators could match. His distinctive investigation style matches up well with how the unnamed undercover investigator behaved aboard the Odell.75 As historian Jennifer Fronc has observed, Oppenheim “was the most adept” of all the COF’s undercover agents “at establishing himself as a regular at neighborhood saloons,” because he took an “active role” relative to other investigators, “[chatting] up waiters,” talking “about (and with) women,” and “hold[ing] forth on horseracing, gambling, and other city pleasures.”76 For these reasons, although the report’s authorship is undoubtedly a matter of educated guesswork, I present the narrative as if Oppenheim were the author and label the unnamed narrator “Oppenheim.”

III. “A Chance to Pull Off a Piece”

David Oppenheim’s general impression of the crowd aboard the Benjamin B. Odell was that it was “fairly well behaved.” He “did not notice very many professional prostitutes,” and saw no “actual soliciting.” However, there seemed “to be quite a few unescorted questionable women and girls aboard.” The undercover investigator claimed in his report to have witnessed more than fifty “pickups” over the course of the evening. In the lower of the steamer’s two saloon decks there was live music, and couples were “shimmying and dancing real raw.” As many as thirty-five couples danced in a small, crowded area that had been cleared out near the piano, which in Oppenheim’s estimation was fit for no more than five couples. Not only was there “no one . . . to stop the couples from dancing as they pleased,” but “in fact the musicians were urging on the couples to shimmy,” and even made attempts later to “promote a shimmying contest between a few couples.”77 In the COF’s view, the fact that waged workers were encouraging passengers to engage in “disorderly” recreational activities this way, and that management neglected to intervene or prevent such behavior would indicate that the Odell’s owners bore a large degree of responsibility for the presence of the “social evil” aboard the packed river steamer. Enhanced methods of supervision were needed in order for the Odell to be transformed from a space of social contagion, a node for the spread of dangerous diseases and immoral attitudes and behaviors, into a sufficiently reputable and “clean” form of leisure.

The Odell had eighty-five to ninety staterooms available for rent that night, according to one crew member Oppenheim interviewed, all of which were occupied by the time Oppenheim had boarded. Sensing that these rooms might be used for “immoral purposes” in the kinds of ways discussed in the earlier writings of Peters, Israels, and others, Oppenheim “watched these staterooms carefully.” Men and women were “coming out of these rooms,” he noted. But he did not witness “any woman flirt with a man and then steer him to her stateroom.” These observations indicated that the staterooms were probably not currently being used for the purposes of organized exploitation of sexual labor.

Casual sexual interactions, however, seemed to be rampant in the Odell’s staterooms. Indeed, the COF probably would have concluded on the basis of Oppenheim’s account that it was possible or even likely given the lack of effective surveillance by management that the staterooms were being used to facilitate some small-scale, informal commercial sexual transactions between semi-professional or “casual” sex workers or “charity girls.” Unlike traditional “prostitution” arrangements, such forms of sexual labor and barter exchange might plausibly have been going on discretely and without the direct knowledge of the boat’s corporate managers. Such activities were camouflaged to a certain extent, since they were often indistinguishable from increasingly mainstream practices of pickup culture.78 The staterooms were private, ask-no-questions spaces. Working-class couples who did not have privacy at home could get intimate in these spaces without raising suspicion. This was useful whether one was looking to engage in casual sex or to transact an exchange of sexual labor for money. Several of the rooms, noted Oppenheim, were shared by two or three couples who were “all bunked together.” “The majority of the women” that he saw coming from these rooms “appeared to be game” (that is, they appeared to be “charity,” or women willing to exchange sexual favors for ticket fare, attention, drinks, food, companionship, or other goods). Oppenheim paid particular attention to room number 28, which was shared by three couples. The women were about eighteen to twenty years of age in appearance, while the men “appeared to be a lot of young toughs.” After watching the room for a while, he noticed that the couples were engaged in a kind of relay system: “two of the couples would leave the room” while the third “would remain there” for some time. “The two couples were giving the third a chance apparently to get away with something,” concluded Oppenheim. This procedure “was repeated till all the couples had had a chance to be in the stateroom alone” for anywhere between twenty-five to thirty minutes. If there was any doubt about what was going on in the room, a porter with whom Oppenheim engaged in conversation confirmed that the couples were “giving one another a chance to pull off a piece.” Later, after the boat had passed the first of two stops in Manhattan at 129th Street, Oppenheim peeked in on some of those staterooms which had just been vacated by disembarking passengers. “The conditions of the rooms,” he wrote, “showed to what purpose they were being used.” Beds were “mussed up very bad, not as if a person had just taken a nap,” but “more like a couple of people . . . had been wrestling on” them. Floors were littered with dirty towels that had “apparently been used for joy towels.”79

“Looking for a Woman”

While aboard the Odell, Oppenheim spoke with several Black employees of the Central Hudson Line, including at least two stewardesses and two porters. (As Belle Israels noted already in 1909, the grand night boats of the Central Hudson Line employed “respectable colored women” to act as “matrons,” but in practice they had no real authority or “moral effect” on the crowd.80) Through these conversations with employees, he learned about some of the surreptitious money-making schemes at work just beneath the radar on the boat, all of which were of potential interest to his superiors.

One porter, John, promised “to look around and see if he couldn’t find a woman” for Oppenheim. It was his first day on the job. Another porter, Cooper, said he regularly sees “a few professional hustlers” aboard the Odell every Sunday. He was, he explained, “on speaking terms” with one of these women, but she was not on board that night and thus he could not introduce her to him. Cooper also claimed that there were “a few” professional sex workers on the boat known to him “by sight.” These women were “out for the money,” said Cooper, but all of them “seemed to have men with them” already tonight. If Oppenheim did succeed in securing a room, Cooper assured him he could take any woman he liked there, since passengers did not have to specify the number of guests up front when renting a room. “It was no one’s business how many” individuals used a stateroom once it was engaged by a passenger, he said. Clearly the boat’s private staterooms provided employees ample opportunities to work hand-in-glove with individual sex workers, helping them secure clients discreetly on commission. Cooper promised he would “do his best to try to pick up a woman” for Oppenheim and to “see if he couldn’t get a stateroom for” him later on, explaining that passengers could remain in their staterooms overnight while the boat was docked at Fulton Street.81

One of the stewardesses, Jennie, told Oppenheim she would “look around and see if she couldn’t find a woman” to put him “next to” after he mentioned he “was looking for a woman.” She said there were “plenty of women” that Oppenheim “ought to be able to pick up on the boat.” Every Sunday there were “a lot of women” on the boat, she said, and she knew “their faces well and could easily tell their business.” She mentioned that “a couple of girls” living in Newburgh worked “this boat regularly,” and that “some of the colored . . . stewardesses on some of the boats of this company have also been doing this business.” They were all under surveillance now, however, “because one of the stewardesses” aboard the steamer Homer Ramsdell “had overdone it.” She had been “caught going into staterooms with men” by the management and discharged. Word on the street was that this woman “handled so many men on each trip” that she “was making more money than the company.” While he spoke with her, Jennie’s roommate approached and asked for the key to their quarters. A man was looking for a room to use “for a while,” the roommate said, and since all the staterooms were booked, she had offered to let the man use their room for a short time. Should he ask for it again, said the roommate, she would lend him the key, at which time Jennie should “stay around and look out.” Clearly the stewardesses were engaged in a side hustle of some sort, capitalizing on the boat’s limited bed space in ways the COF’s leadership would almost certainly reckon as morally dangerous. Though all the staterooms had been engaged by the time Oppenheim boarded the Odell in Newburgh, Jennie declared he would probably be able to remain on the Odell all night with whomever he liked, since the purser “re-rents the rooms again after the people that were occupying them leave the boat” at the 129th Street stop. If he waited for the final leg of the journey to Fulton Street, he could almost certainly get a room. There were a few detectives lurking about, she said, but Oppenheim would not have to worry; once he rented a room, it would be “none of their business who occupies” it. This system deviated greatly from how hotel rentals worked within the city proper. As Oppenheim knew well from personal experience, hotels in New York were barred from admitting guests without baggage, and clerks were supposed to refuse service to “suspicious” transients. On the Odell by contrast, no one was inquiring much at all about how rooms were used, or indeed about which passengers were coming and going from them or why.82

“Companionship and a Little Fun”

Oppenheim got “next to” two women while aboard the Odell that night. The first woman was introduced to him by an old acquaintance of his, Jack Bancroft, who happened to be working as a singer on the Odell. Bancroft worked as a waiter at several restaurants in the city, which is where he had met Oppenheim (whom he did not suspect to be an undercover vice investigator working for the COF). Indeed, Oppenheim’s intimate knowledge of working-class leisure culture made him a valuable asset to the COF, even as his approach necessitated greater participation in the activities its members hoped to inhibit. Because he became personally acquainted with many workers employed in various amusement and drinking establishments across the city, he enjoyed, in Fronc’s words, a “familiarity with the staff in many places under investigation” that often “yielded invaluable information that was otherwise unavailable.”83 It was Bancroft’s first day on the job, so he “didn’t know much,” but he said he would “try to get some girl” for the investigator anyway. At length Bancroft introduced Oppenheim to a young woman named Eva Gould, a recent transplant from Cleveland residing in a furnished room at 127 West 77th Street. According to the business phone number she provided Oppenheim, Eva worked at an office off Madison Square Park, probably as a stenographer, telephone operator, or secretary. Eva was “not a professional prostitute,” wrote Oppenheim in his report, but, as Bancroft separately confirmed, she appeared to be “game.” When Oppenheim told her he was “trying to get a stateroom,” Eva replied, “Haven’t you got one, I thought you had one.” This remark reinforced the investigator’s earlier assessment that the staterooms were ideal spaces for sex and were thus probably being used by couples of all sorts for what the COF considered to be “immoral purposes.” It also confirmed that Eva was probably “game,” that is, that she was willing to have casual sex without expectation of monetary payment. Eva told the undercover investigator she had “made several trips on these boats and always has a little fun.” Jennie, the stewardess with whom he spoke later in the evening, observed Oppenheim speaking with Eva and confirmed that she had indeed seen her on the boat a few times previously. Before parting from him, Eva told Oppenheim that any time he took “the night boat to Albany,” or if he “wanted to take a trip of that kind on a Saturday night, she would come along and stay” the night with him in Albany. She gave him her telephone number and they parted ways.84

The second “game” woman Oppenheim picked up aboard the Odell that night, Nellie, was a schoolteacher from a small town north of Boston who had been staying for a few weeks at the Cambridge Hotel, located at 37-42 Nevins Street, Brooklyn. Nellie explained that she had been “trying to make” Oppenheim all night but had seen him speaking with the other woman, with whom she assumed he had partnered up. Like Eva, Nellie was “not a professional prostitute,” but was instead a workingwoman interested in casual sex. Rather than waiting for him “to ask her what was doing,” she “started the subject,” bluntly stating that she was “lonesome and wants company.” “We are all human and want companionship and a little fun,” she said. Then she asked if the two of them “couldn’t get a stateroom” and “both stay over” aboard until the morning, when “it was time for her to get to work” at the office on Broadway where she was employed. Alternatively, he could accompany her back to the Cambridge Hotel. Though the place was “pretty strict,” she said, Oppenheim could come up there by himself, register a room separately, and then “come into her room” without raising suspicions.85

Though Nellie did not admit it directly, “from her talk” Oppenheim came to understand that “there had been someone in her room at the Cambridge before.” However, since apparently this had happened “without the knowledge of the proprietor” of the hotel, it did not appear that the management of the Cambridge was running the place in an openly “disorderly” manner––a key distinction from the perspective of COF members, for whom property owners’ willful participation in commercialized disorder represented the gravest danger to public health and morals. On the other hand, Nellie said she was “positive” that the hotel saloon remained open after one o’clock in direct violation of the late-night restrictions the COF and police department had actively been enforcing across the city since America’s entry in World War I two years prior. She also mentioned she was “overanxious for a little whiskey” and that she hoped Oppenheim might be able to score some once they arrived at Fulton Street.86

“Ain’t a Drop in the Place”

When the Benjamin B. Odell docked at Pier 24, Oppenheim and Nellie disembarked together. Rather than taking her directly back to the Cambridge Hotel where she was staying, Oppenheim set about trying to find her “a drink of whiskey” as she requested.87 He asked a few men on the street where he “could get something stronger than 2.75 beer.”88 After being refused entry to one establishment, the duo was admitted around midnight to the Press Café, located at 93 Park Row near city hall. When the server came for their orders, Oppenheim at first “didn’t ask for whiskey” directly, but instead said cryptically, “Do the best you can,” urging him to serve them “the strongest you got.”89

When the server returned some minutes later with port wine, Oppenheim, unsatisfied, asked whether he “couldn’t give” them “a little whiskey.” “There ain’t a drop in the place,” replied the server. But this did not sit right with Oppenheim; a stand keeper nearby had told him and his female companion that he was certain they “could get the stuff at the Press,” since it was well known in the area “that they [were] not a bit careful in handing out whiskey across the bar.” As they went to leave the café, resigned that the sever was not going to aid them in their search, Oppenheim stopped to speak with a man seated near the door whom he assumed was “connected with the premises.” He told the man that they had been “trying to get a little booze” but had been unsuccessful, then asked whether “he didn’t know of any place where [they] could get it.” The man responded by inquiring if they were looking for a pint or half pint of whiskey, to which Oppenheim simply replied, “yes.” The man said he would see what he could do, and reappearing several minutes later, he told them the place had no pints or half pints, but if Oppenheim “was willing to spend a dollar and a half,” plus twenty-five cents to the man “for the trouble,” they would fill a soda water bottle with the stuff for him. Oppenheim agreed, and around ten minutes later the man returned with a soda water bottle full of whiskey. Having found what they were after, Oppenheim escorted Nellie back to the Cambridge Hotel. Though she wanted him to rent a room so they could spend the night together, he excused himself, promising to call. It had been an uncommonly informative and eventful night.

Conclusion

There was “plenty of the charity stuff” aboard the Odell, concluded Oppenheim. While he had discovered vague indications that professional sex workers were regularly using steamboats to conduct business, there did not in his view “seem to be much of the commercialized vice aboard.” However, based on the limited information he was able to gather during the voyage, Oppenheim concluded confidently that he had “no doubt” that the management knew “for what purpose their staterooms [were] being used.”90

Examination of conditions aboard the Odell revealed to the COF the extent to which Hudson River steamers catering to weekend excursioners operated outside of the norms of behavior and systems of police surveillance prevalent in Manhattan, where liquor prohibition and a variety of overlapping draconian schemes of wartime social control and moral policing were actively working to discipline and restrict wage-earning women’s sexual autonomy, leisure-time activities, and heterosocial amusement and courtship practices in commercial amusement spaces.

In the eyes of Oppenheim’s employers, the apparent lack of regulation of dancing and entertainment by the boat’s management, the general absence of adequate systems for supervising passengers’ social conduct, and the observed practice of renting out staterooms (and, apparently, of staff quarters) indiscriminately for short periods would have constituted clear indications that the Odell––and, presumably, other Hudson River steamboats enjoyed by huge crowds of amusement-seekers––presented considerable hazards to public social and moral “hygiene.”

Summer steamboat excursions provided wage-earning passengers hailing from a broad cross-section of American society with valuable opportunities to socialize, find love, and/or get physically intimate. Shorn of mainland “protections,” relatively under-monitored steamers like the Odell constituted liminal, “heterotopic,” fringe spaces that floated in a state of pseudo-autonomy with respect to the dominant, repressive norms of social and sexual conduct enforced across New York City during the war years.

Notes

- Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” translated by Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 27, https://doi.org/10.2307/464648. For Foucault, heterotopias are transitory “counter-sites,” where, for particular historical reasons, certain cultural norms and practices regulating everyday social space are restaged, contested, and/or inverted. ↩

- The Benjamin B. Odell was a 280-foot steel propellor steamer that boasted ample capacity for freight and passengers. Its reinforced hull was ideal for cutting through frozen waterways. For additional photographs of the Odell, see “Latest Maritime News in Pictures,” Marine Review 46, no. 6 (June, 1916): 204, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112043103727?urlappend=%3Bseq=218%3Bownerid=115842177-224; William H. Ewen Jr., Steamboats on the Hudson River (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2011), 39, 41; “Steamer Benjamin B. Odell,” Hudson River Night Boat Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum, 1911, https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/hrmm/id/480/rec/1; “Sunday News: Steamer Benjamin B. Odell, 1911–1937,” Hudson River Maritime Museum History Blog, April 26, 2020, https://www.hrmm.org/history-blog/sunday-news-steamer-benjamin-b-odell-1911-1937. ↩

- The so-called Chicago Race Riot also coincidentally began on July 27, 1919, the same day the events in the report discussed in this article took place. The riot, which lasted more than three days and resulted in the deaths of more than twenty Black people at the hands of a mob, was sparked by conflicts over that city’s racially segregated beaches. Carl Sandburg, The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1919), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044020443180; Cameron McWhirter, Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2011). ↩

- For journalistic coverage of Hudson River steamboats as popular courtship spaces, see “Day Line Taboos Spooning,” New York Times, June 13, 1920, 11, https://nyti.ms/3AlVuEC; Helen Bullitt Lowry, “Wanted: A New O. Henry,” New York Times, June 20, 1920, Section 7, 4, https://nyti.ms/31YA2qw; Marguerite Dean, “Gotham’s High Cost of Loving!” Evening World Daily Magazine (New York), July 14, 1920, 21, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030193/1920-07-14/ed-1/seq-21/. ↩

- Scott W. Stern, The Trials of Nina McCall: Sex, Surveillance, and the Decades-Long Government Plan to Imprison ‘Promiscuous’ Women (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018). ↩

- Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986), 121. ↩

- State of New York, Twentieth Annual Report of the Commissioners of the Palisades Interstate Park (Albany: J. B. Lyon Co. Printers, 1920), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044097760516; Rand McNally Hudson River Guide to Places of Interest to Tourists and Excursionists (New York: Rand McNally & Co., 1915), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t84j11s0v. ↩

- Ewen, Steamboats on the Hudson, 17. ↩

- Allyne H. Lange, forward to Ewen, Steamboats on the Hudson, 7. ↩

- Andrew W. Kahrl, “‘The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness’: Steamboat Excursions, Pleasure Resorts, and the Emergence of Segregation Culture on the Potomac,” Journal of American History 94, no. 4 (March 2008): 1114, 1116, https://doi.org/10.2307/25095322. Kahrl notes that this “golden age” of urban amusements was based on the systematic exclusion of Black Americans. As Hartman observes, the COF, believing sociability across “the color line” to be detrimental to social order, employed undercover investigators and cooperated with business interests to enforce racial segregation extralegally in working-class recreation spaces “as a way to maintain the health and morality of the social body.” Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), 248. On the COF’s efforts to surveil Black commercial and private leisure spaces and furnished room districts, including both its independent efforts and its cooperative work with police officials, see Jennifer Fronc, “The Horns of the Dilemma: Race Mixing and the Enforcement of Jim Crow in New York City,” Journal of Urban History 33, no. 1 (November 2006): 8, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0096144206290263; Stephen Robertson, “Harlem Undercover: Vice Investigators, Race, and Prostitution, 1910–1930,” Journal of Urban History 35, no. 4 (May 2009): 491–492, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144209333370; Chad Heap, Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885–1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 144; Stephen Robertson, Shane White, Stephen Garten, and Graham White, “Disorderly Houses: Residences, Privacy, and the Surveillance of Sexuality in 1920s Harlem,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 21, no. 3 (September 2012): 443–466, https://doi.org/10.7560/jhs21303. ↩

- Peiss, Cheap Amusements, 4. See also George W. Alger, “Leisure–for What?” Atlantic Monthly 135, no. 4 (April 1925): 483–492, https://www.proquest.com/docview/203622608; Roy Rosenzweig, Eight Hours for What We Will: Workers and Leisure in an Industrial City, 1870–1920 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 64. ↩

- The saloon’s status as a site of “alternative” rather than “oppositional” working-class culture, that is, as an ameliorative space where class tensions were lessened and the dangerous, anarchistic ideas in the mind of the working man were “ironed out,” was reckoned by leading “wets” as a point against prohibition. Benjamin De Casseres, “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Unhappiness,” New York Times Magazine, January 18, 1920, 6, https://nyti.ms/3yPvOgV. ↩

- Peiss, Cheap Amusements, 6. As one influential reformer wrote of the attitude of New York’s wage-earning women and girls in 1909, “No amusement is complete in which ‘he’ is not a factor.” Belle Lindner Israels, “The Way of the Girl,” The Survey 22, no. 14 (July 1909): 486, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015027568255?urlappend=%3Bseq=506%3Bownerid=9007199255370796-516. “The working girl’s pleasures,” wrote the COF’s Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch in 1917, pivoted chiefly on “dancing, the theatre, and the young man.” Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, The City Worker’s World in America (New York: Macmillan Company, 1917), 131, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044014548242; emphasis added. ↩

- Elizabeth Alice Clement, Love for Sale: Courting, Treating, and Prostitution in New York City, 1800–1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 50. In Simkhovitch’s words, since “play, leisure, freedom,” were “all bound up in the word recreation,” to deny recreation to a large portion of the population was “to make men a means to an end––the one unpardonable sin for a democracy.” Simkhovitch, The City Worker’s World, 138. ↩

- Clement, Love for Sale, 51. ↩

- Susan M. Kingsbury, “Standards of Living and the Self-Dependent Woman,” Proceedings of the Academy of the Political Science in the City of New York 1, no. 1 (October 1910): 72, https://doi.org/10.2307/1171698. On women’s wages, work conditions, and living standards in early-twentieth-century New York, see Louise Bolard More, Wage-Earners’ Budgets: A Study of Standards and Cost of Living in New York City (New York City: Henry Holt and Company, 1907); Robert Coit Chapin, The Standard of Living Among Workingmen’s Families in New York City (New York: Charities Publication Committee, 1909); Annie Marion MacLean, Wage-Earning Women (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1910); Sue Ainslie Clark and Edith Wyatt, “Working-Girls’ Budgets,” McClure’s Magazine 36, no. 1 (November 1910): 70–86, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.47963802?urlappend=%3Bseq=78%3Bownerid=13510798902658783-92; Mary White Ovington, “The Colored Woman as a Bread Winner,” in Half a Man: The Status of the Negro in New York (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1911), 138–169; State of New York, Third Report of the Factory Investigating Commission, 1914 (Albany: J. B. Lyon Co. Printers, 1914), 100–101, 143–166, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t0cv4dp3q; Mary Van Kleeck, Women in the Bookbinding Trade (New York, Survey Associates, Inc., 1913), 72–100; Harriet McDoual Daniels, The Girl and Her Chance: A Study of Conditions Surrounding the Young Girl Between Fourteen and Eighteen Years of Age in New York City (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company), 11–13, 44–77, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t9765dr1q; Charles E. Persons, “Women’s Work and Wages in the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 29, no. 2 (February, 1915): 201–234, https://doi.org/10.2307/1884958; Simkhovitch, The City Worker’s World, 54–59. ↩

- Maude E. Miner, Slavery of Prostitution: A Plea for Emancipation (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1916), 297, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433075969083. ↩

- Miner, Slavery of Prostitution, 77. See also Simkhovitch, The City Worker’s World, 130. ↩

- On the practice of “standing treat” or “charity,” see Israels, “The Way,” 487–489; Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, “A New Social Adjustment,” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York 1, no. 1 (October 1910): 87, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1171699; Chicago Vice Commission, The Social Evil in Chicago: A Study of Existing Conditions with Recommendations by the Vice Commission of Chicago: A Municipal Body Appointed by the Mayor and the City Council of the City of Chicago, and Submitted as its Report to the Mayor and City Council of Chicago (Chicago: Gunthorp-Warren Print Company, 1911), 267, http://id.lib.harvard.edu/aleph/002172977/catalog; Winthrop D. Lane, “Under Cover of Respectability: Some Disclosures of Immorality Among Unsuspected Men and Women,” The Survey 35, no. 26 (March 25, 1916): 746, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101066882786?urlappend=%3Bseq=788%3Bownerid=27021597767051255-888; John G. Buchanan, “War Legislation against Alcoholic Liquor and Prostitution,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 9, no. 4 (February 1919): 526, https://doi.org/10.2307/1134127; Peiss, Cheap Amusements; Gilfoyle, City of Eros, 311; Kathy Peiss, “Charity Girls and City Pleasures,” Magazine of History 18, no. 4 (July 2004): 14–16, https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/18.4.14; Clement, Love for Sale. Some Progressive Era social scientists argued that the use of such terminology by reformers and social workers to describe emergent dating norms was inappropriate. For English sexologist Havelock Ellis, for instance, to use the term “charity girls” when referring to young women who engaged in extramarital intimacy was to “accept the prostitute’s standpoint.” Havelock Ellis to Frederick H. Whitin, July 16, 1925, “Ellis, Havelock,” Box 11, Committee of Fourteen records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library (hereafter “C14”). ↩

- On the COF’s wartime contributions to the federal government’s policing of sexual and moral conditions near military camps for the War Department’s Commission on Training Camp Activities, see William F. Sloane to the Committee of Fourteen, May 23, 1917, “Pfeiffer, Timothy N.,” Box 24, C14; Captain Timothy N. Pfeiffer to Francis Louis Slade, September 4, 1917, “Pfeiffer, Timothy N.,” Box 24, C14; Committee of Fourteen, Annual Report for 1916–1917 (New York, 1918), 7–10, 15–20. COF member Maude E. Miner organized and chaired the Commission’s committee on Protective Work for Girls. See Maude E. Miner, “The Girl Problem in War Time,” General Federation Magazine 17, no. 5 (May 1918): 13–14; Edna Huber Church, “Women Police of Military Camps Helping to Win the War,” South Bend News-Times, May 20, 1918, 9, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87055779/1918-05-20/ed-1/seq-9/; Maude Miner Hadden, Quest for Peace: Personal and Political (Washington, D.C.: Farrar, 1968), 161–176. ↩

- On the relation between wartime prohibition and demobilization, see A Woman War Worker, “Our Bad Boys in France,” New York Times Magazine, August 24, 1919, 7, https://nyti.ms/3ZhpT1l. Buchanan, “War Legislation.” On demobilization and “demoralization,” see Philip Gibbs, “Effects of the War on Soldiers’ Minds,” New York Times, June 1, 1919, Section 4, 1, https://nyti.ms/3H5pk0x. On shifts in New York City’s clandestine sexual economy wrought by wartime prohibition and the COF’s quest to track them, see Austin Gallas, “The Price of the Ride in New York City: Sex, Taxis, and Entrepreneurial Resilience in the Dry Season of 1919,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 31, no. 1 (January 2022): 89–114, https://doi.org/10.7560/jhs31104. On the wartime panic over “venereal disease” and promiscuity, see especially William F. Snow, “Social Hygiene and the War,” Social Hygiene 3, no. 3 (July 1917): 417–428, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3154437?urlappend=%3Bseq=439%3Bownerid=9007199274480081-453; John D. Rockefeller, Jr., “U.S. First to Organize Morally Against Enemy,” Trench and Camp (Admiral, Maryland), December 26, 1917, 7, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92068220/1917-12-26/ed-1/seq-7/; Raymond B. Fosdick, “The Program of the Commission of Training Camp Activities with Relation to the Problem of Venereal Disease,” Social Hygiene 4, no. 1 (January 1918): 71–76, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3154438?urlappend=%3Bseq=91%3Bownerid=9007199274480306-95; Seale Harris, “G. H. Q. Bulletin No. 54 on the Venereal Disease Problem,” Social Hygiene 5, no. 3 (July 1919): 301–309, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3154439?urlappend=%3Bseq=313%3Bownerid=9007199274480547-341. ↩

- Winthrop D. Lane, “Girls and Khaki,” The Survey 39, no. 9 (December 1, 1917): 236, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015013338176?urlappend=%3Bseq=252%3Bownerid=13510798884828139-272. See also Miner, “The Girl Problem,” 15–16. ↩

- Older criminological narratives emphasizing individual failure persisted, however. See especially Terry G. Lilley, Chrysanthi S. Leon, and Anne E. Bowler, “The Same Old Arguments: Tropes of Race and Class in the History of Prostitution from the Progressive Era to the Present,” Social Justice 46, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 33, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2439672126. ↩

- Peiss, Cheap Amusements, 178. ↩

- John Willis Slaughter, quoted in “Plans for Dry New York,” New York Times Magazine, June 8, 1919, 2, https://nyti.ms/3Emss6c. ↩

- Belle Lindner Israels, “Regulation of Public Amusements,” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York 2, no. 4 (July 1912): 126, https://doi.org/10.2307/1171971. In Israels’s words, “industrial activity demands diversion.” Israels, “The Way,” 486. For related Progressive theorizations of recreation, see Frances A. Kellor, “Protection of Immigrant Women,” Atlantic Monthly 101, no. 2 (February 1908): 253, https://www.proquest.com/docview/203576464; Lee F. Hanmer, “A Playground Meeting with Real Play,” The Survey 26, no. 9 (May 27, 1911): 333–337, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924065807103?urlappend=%3Bseq=379%3Bownerid=13510798902121217-437; Miner, Slavery of Prostitution, 79–86; Simkhovitch, The City Worker’s World, 52, 108–139. ↩

- Belle Lindner Israels, quoted in “Dance Halls to Prove Vice Is Not Fun’s Real Comrade,” New York Tribune, December 22, 1912, 4, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1912-12-22/ed-1/seq-24/. See “Supervision of the Dance Restaurants Frequented by Middle Class Girls (and their Mothers) is the Most Immediate Need of New York, According to Mrs. Henry Moskowitz,” New York Tribune, May 27, 1915, 7, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1915-05-27/ed-1/seq-7/. ↩

- Simkhovitch, “A New Social Adjustment,” 86–87. “The social evil” was a catch-all term favored by reformers and sociologists beginning in the postbellum period that retained wide usage throughout the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era. It denoted prostitution and other forms of illicit or “immoral” sexual activity and gestured to a wide spectrum of related “disorderly” behaviors and disreputable commercial practices seen as hazardous to moral, economic, and social welfare. Committee of Fifteen, The Social Evil: With Special Reference to Conditions Existing in the City of New York (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1902), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/dul1.ark:/13960/t05x7cm79; Research Committee of the Committee of Fourteen, The Social Evil in New York City: A Study in Law Enforcement (New York: Andrew H. Kellogg Company, 1910), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/dul1.ark:/13960/t48q13x3s; Maude E. Miner, “The Chicago Vice Commission,” The Survey 26, no. 6 (May 6, 1911): 217, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924065807103?urlappend=%3Bseq=251%3Bownerid=13510798902121217-281; Jane Addams, “A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil,” McClure’s Magazine 38, no. 1 (November 1911): 4, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924065818407?urlappend=%3Bseq=15%3Bownerid=13510798902588912-19; George J. Kneeland, “Commercialized Vice,” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York 2, no. 4 (July 1912): 127–129, https://doi.org/10.2307/1171972; Val Marie Johnson, “Defining ‘Social Evil’: Moral Citizenship and Governance in New York City, 1890–1920” (PhD diss., New School University, 2003), 4, 79, https://www.proquest.com/docview/288145190. ↩

- Joseph Lee, “Sunday Play,” The Survey 25, no. 1 (October 1): 58, 61, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924065807095?urlappend=%3Bseq=79%3Bownerid=13510798902121051-85. Lee was an outspoken eugenicist who publicly supported the reactionary Immigration Restriction League. A. T. Lane, “American Trade Unions, Mass Immigration and the Literacy Test: 1900–1917,” Labor History 25, no. 1 (1984): 21, https://doi.org/10.1080/00236568408584739. ↩

- Amy E. Spingarn, “Summer Vacations for Working Girls,” The Survey 22, no. 14 (July 1909): 521, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.32106005425118?urlappend=%3Bseq=635%3Bownerid=9007199273627428-671. ↩

- Peiss, Cheap Amusements, 179. ↩

- Miner, Slavery of Prostitution, 79. ↩

- Simkhovitch, “A New Social Adjustment,” 86. ↩

- Don S. Kirschner, “The Ambiguous Legacy: Social Justice and Social Control in the Progressive Era,” Historical Reflections 2, no. 1 (July 1975): 74, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41298660. On the assault on urban red-light districts and the decline in popularity of commercial sex in American culture during the early decades of the twentieth century, see Timothy J. Gilfoyle, “Undermining the Underworld,” in City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790–1920 (New York: Norton); Mara L. Keire, “The Vice Trust: A Reinterpretation of the White Slavery Scare in the United States, 1907–1917,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 1 (Fall 2001): 5–41, https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2001.0089. ↩

- Israels, “Regulation,” 125. ↩

- Israels, quoted in “Dance Halls,” 4. ↩

- Committee on Amusement Resources of Working Girls, A Report of the Committee on Amusement Resources of Working Girls (New York: Peck Press Printers, 1912), 6, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112098444026. ↩

- Kirschner, “The Ambiguous Legacy,” 75. On objectionable dancing styles and dance hall reform, see Belle Lindner Israels, “How We Broke the Curse of the Dance Halls,” Omaha Daily Bee, February 16, 1913, 19, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn99021999/1913-02-16/ed-1/seq-19/. ↩

- Rosenzweig, Eight Hours, 144. ↩

- Elisabeth I. Perry, “‘The General Motherhood of the Commonwealth’: Dance Hall Reform in the Progressive Era,” American Quarterly 37, no. 5 (Winter 1985): 733, https://doi.org/10.2307/2712618. ↩

- Keire, “The Vice Trust,” 21. ↩

- Lane, “Under Cover,” 749. ↩

- “Says Women Solicit Openly on Passenger Steamer,” Day Book (Chicago), September 9, 1913, 7, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045487/1913-09-09/ed-1/seq-7/. As a result of this complaint, a probe of moral conditions aboard excursion boats operating between Chicago and other cities was conducted by Charles F. De Woody, the Department of Justice’s chief “white slavery” investigator, whom Pretzel consulted following his much-publicized experience. “Local Doings in Tabloid Form,” Day Book (Chicago), September 11, 1913, 5, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045487/1913-09-11/ed-1/seq-5/; “Inquiry in Alleged Vice,” Prescott Daily News (Arkansas), September 12, 1913, 1, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90050307/1913-09-12/ed-1/seq-1/. ↩

- Louise de Koven Bowen, The Road to Destruction Made Easy in Chicago (Chicago: Juvenile Protective Association of Chicago, 1916), 4, https://archive.org/details/roadtodestructi00chicgoog. See Juvenile Protection Association of Chicago, Fiftieth Annual Report, 1915–1916 (Chicago), 19, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112107815380. ↩

- Chicago Vice Commission, The Social Evil in Chicago, 268. See also Jane Addams, “A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil: Chapter IV: Tragedies of Lonely and Unprotected Girls,” McClure’s Magazine 38, no. 4 (February 1912): 474, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924065818407?urlappend=%3Bseq=483%3Bownerid=13510798902588912-491. ↩

- Louise de Koven Bowen, Safeguards for City Youth at Work and at Play (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914), 38–39, https://archive.org/details/safeguardsforcit00boweuoft/mode/thumb?ref=ol&view=theater. ↩

- De Koven Bowen, The Road to Destruction, 4. Vice investigators worried male “cadets” preyed upon vulnerable women and girls aboard excursion boats. See especially George J. Kneeland, Commercialized Prostitution in New York City (New York: Century Company, 1913), 86, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t49p2z581?urlappend=%3Bseq=9. ↩

- Israels, “The Way,” 491. ↩

- Israels, “The Way,” 491–492. ↩

- Israels, “The Way,” 496. ↩

- Committee on Amusement Resources of Working Girls, A Report, 8–9. ↩

- Israels, quoted in “Dance Halls,” 4. ↩

- “Richard Henry Edwards, Popular Amusements (New York: Association Press, 1915), 121. ↩

- John P. Peters, “Suppression of the ‘Raines Law Hotels,’” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 32, no. 3 (November 1908): 96, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000271620803200311. ↩

- Gilfoyle, City of Eros, 304; Val Marie Johnson, “‘Look for the Moral and Sex Sides of the Problem’: Investigating Jewishness, Desire, and Discipline at Macy’s Department Store, New York City, 1913,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 18, no. 3 (September 2009): 461, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20542732. ↩

- Mara L. Keire, “The Committee of Fourteen and Saloon Reform in New York City, 1905–1920,” Business and Economic History 26, 2 (Winter 1997): 574, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23703041. See Kneeland, Commercialized Prostitution, 255; John P. Peters, “The Story of the Committee of Fourteen of New York,” Social Hygiene 4, no. 3 (July 1918): 347–388, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044011640745; Katherine Wright, “Sightseers End Women’s Night Court,” New York Tribune, August 11, 1905, 5, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1918-08-11/ed-1/seq-25/; Committee of Fourteen, Annual Report for 1919–1920 (New York, 1920), 6, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nnc1.ar01729594?urlappend=%3Bseq=9%3Bownerid=109705471-13. ↩

- On “Raines Law” hotels and the COF’s fight against “commercialized vice” within them, see John P. Peters, letter to the editor, “The Liquor Traffic,” Sun (New York), March 30, 1906, 6, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1906-03-30/ed-1/seq-6/; Peters, “Suppression,” 96; “Blow at Lawless Saloons,” New York Times, August 24, 1909, 2, https://nyti.ms/3EHmVsN; “Business Men Who Are Quick to Take Prostitutes’ Money,” New-York Daily Tribune, July 10, 1910, Part IV, 6, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1910-07-10/ed-1/seq-48/; Jacob Ruppert, Jr., “Closing Raines Law Hotels: Business Interests Working with the Committee of Fourteen,” no date, file “Brewers, 1909-1910,” Box 10, C14; Maude E. Miner, “The Problem of Wayward Girls and Delinquent Women,” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York 2, no. 4 (July 1912): 132, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1171973; George Haven Putnam, Memories of a Publisher, 1865–1915 (New York: George P. Putnam’s Sons, 1923), 351–352, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b4027349; Willoughby Cyrus Waterman, Prostitution and its Repression in New York City, 1900–1931 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), 32–34, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/inu.32000006213450. ↩

- Peters, “The Story,” 384. ↩

- Jennifer Fronc, New York Undercover: Private Surveillance in the Progressive Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 68, 93. ↩

- Thomas C. Mackey, Pursuing Johns: Criminal Law Reform, Defending Character, and New York City’s Committee of Fourteen, 1920–1930 (Columbus: Ohio State University, 2005), 203. ↩

- “Surveillance” implies systematized observation structured upon an uneven power relationship between viewer and viewed, with the former in a position of dominance. Mark Andrejevic, “Automating Surveillance,” Surveillance and Society 17, no. 1/2 (March 2019): 8, https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12930. On the COF’s “surveillance,” see Fronc, New York Undercover, 66–122; Johnson, “Look for the Moral,” 458, 477; Robertson, White, Garten, and White, “Disorderly Houses.” ↩

- Fronc, “The Horns of the Dilemma,” 5. ↩

- Graham Taylor, “Recent Advances Against the Social Evil,” The Survey 17, no. 24 (September 7, 1910): 861, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015010567710?urlappend=%3Bseq=874%3Bownerid=9007199255370507-890. ↩

- Fronc, New York Undercover, 68. ↩

- Peters, “The Story,” 366. The bond was so tight that Mayor Hylan publicly lambasted the COF’s unchecked authority over police. Gallas, “The Price of the Ride,” 99. The COF also oversaw the city’s Women’s Court, which was created following a COF investigation into New York’s lower courts. Frederick H. Whitin, “The Women’s Night Court in New York City,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 52 (March 1914): 181–187, https://doi.org/10.1177/000271621405200122; Peters, “The Story,” 370; Mackey, Pursuing Johns, 4, 206. Years later, the COF’s reputation suffered when this arrangement was excoriated by well-known police figures. “Committee of Fourteen Dictates Vice Arrests,” New York Times, March 27, 1931, 2, https://nyti.ms/3c9jEJ9. ↩

- Stern, The Trials of Nina McCall, 29. ↩

- On the ethical conundrums provoked by the COF’s undercover tactics, see Gary T. Marx, Undercover: Police Surveillance in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 30; Fronc, “The Horns of the Dilemma,” 21. For the COF’s publicly stated arguments in favor of entrapment in prostitution cases and lower standards of evidence in disorderly house cases, see Frederick H. Whitin, “Disorderly House Evidence,” Vigilance 25, no. 1 (January): 21–28; “Cleaning Up New York,” National Municipal Review 12, no. 11 (November 1923): 661, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ncr.4110121109. ↩

- Fronc, “The Horns of the Dilemma,” 7. ↩

- Miner, Slavery of Prostitution, 86. ↩

- Miner, Slavery of Prostitution, 263. ↩

- This aligned with John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s distaste for “sensational” methods. John D. Rockefeller Jr., The Origin, Work, and Plans of the Bureau of Social Hygiene (New York, 1913), 2, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112060096291; Keire, “The Vice Trust,” 10. Israels’s committee, of which the COF’s Frederick Whitin was a member, also promised the companies not to publish details of its investigations––unless “a more general scheme of education” was deemed appropriate. Committee on Amusement Resources of Working Girls, A Report, 9. ↩

- Report on “Steamer Benj. B. Odell, Central Hudson Line,” July 27, 1919, “Steamboats,” Box 24, C14 (hereafter “Benj. B. Odell, C14”). ↩

- On COF investigators’ writing and recording practices, see Fronc, New York Undercover, 78. ↩

- Report of David Oppenheim, “Street Conditions, Manhattan,” April 3, 1919, “1919 #3,” Box 34, C14; report of David Oppenheim on Orange Grove de Dance, April 9, 1919, “1919 #3,” Box 34, C14. ↩

- On Oppenheim’s schmoozing and information gathering skills, see Robertson, “Harlem Undercover,” 491–492. ↩

- Fronc, New York Undercover, 77, 82. ↩

- “Benj. B. Odell,” C14. ↩

- Heap, Slumming, 67. ↩

- “Benj. B. Odell,” C14. ↩

- Israels, “The Way,” 492. ↩

- “Benj. B. Odell,” C14. ↩

- “Benj. B. Odell,” C14. ↩

- Fronc, New York Undercover, 82. ↩