In February 2013, Coca-Cola released a promotional video showing a group of Singaporean taxi drivers surprised with a reunion dinner during the Lunar New Year, a festive tradition for the ethnic Chinese that the drivers had to forsake because of work commitments. These older, middle-aged drivers were lauded as hardworking “unsung heroes,” workers who sacrificed their reunion dinner to ply the streets to make a living for their families. “I have no rest,” expressed a sixty-four-year-old driver who drives twelve hours a day. “I only sleep for about five hours a night before I have to drive again.” This trope of the diligent, working-class, older family taxi-man—resonating with a national narrative of working-class moral luminosity—establishes their deservingness of the prize delivered at the end: a dinner with their families and cover of their earnings for the day.

This impression, however, would be challenged barely two weeks later upon Uber‘s entry into Singapore. In what would mark the beginning of a decade-long period of “disruption,” gig platforms and public discourse would repeatedly present the taxi driver as a relic of an outdated industry. As some of the earliest ads for Uber in Singapore suggest, the new driver was to be a younger, hipper entrepreneurial subject, someone who hustles for dreams rather than survival.1 Articles and commentaries would affirm this transition over the decade, establishing that “the elderly workhorse uncle is a dying breed” and asking “must taxi uncle give way to Uber driver” (fig. 1).2

By now, such Schumpeterian accounts of creative destruction should well be familiar. Writings on the harms of platform companies extend globally, marking the promises and pitfalls of platformed gig work.3 Yet, as thoughtful as these discussions are, less attention has been given to nuances of the alternate governmentalities coalesced around the “gig”: the capacity of the job, with its conjunct instability, to invoke familialist and nationalist subjectivities amongst the working classes. As the 2013 pre-Uber video and its dramatically altered aftermath suggest, what is central to the arrival of platformed gig work is not simply a transformation of work; it also opens a pressing question: what is gig work meant to do?4 In diagnosing the “taxi uncle” as a “dying breed,” a shift in the biopolitics of work is suggested.5 The change in the gig worker’s image also relates to who gig work is meant to support, and the kinds of lives imagined to be cultivated through this labor.

This article looks backwards into the historical development of the taxi industry in Singapore to contribute to discussions of platform gig work in the present. What taxis show clearly is that the gig work in Singapore, and to some extent its neighboring regions of Southeast Asia, cannot be narrowly understood as “work”—a means to make a living. Rather, it is a steering mechanism to create a particular kind of working-class subject and a family. In this sense, institutionalized gig work in Singapore began as a way to “make live,” the term referencing Michel Foucault’s argument that biopolitics is centered around encouraging particular formations of life through adjustments of security.6 Surrounding the idea of “gig work” is an imaginary of the gig worker’s life, and the purpose that gig work should serve towards encouraging these ends.

Histories and Biopolitics of Gig Work

For the large part, research around gig work has been characterized by what Bingqing Xia calls an “exploitation paradigm.”7 Etymologically, the “gig” refers to the temporary, usually one-night engagement of musicians and comedy performers in a club. In historicizing the term as it is used today, scholars have expanded the boundaries around gig work, drawing its connection to trends of outwork, homework, casualized and seasonal work, emphasizing precariousness, piecemealing, and the lack of legal and institutional support as its unifying thread.8 Here, a lineage of dockworkers, women and children outworkers in the garment trade, and agricultural seasonal laborers join modern platformed cloud and geographically tethered workers to make up the longstanding chorus of the gig, suggesting that the characteristics associated to platformed gig work are “as old as capitalism, perhaps even older.”9

This historicization is significant for it points to the longer project of class warfare, racial capitalism, and its influence on the biopolitics of work.10 Insecure labor has been the reality of many historically and in the present, and the burden of precariousness has never been evenly distributed. Immigrants, racial minorities, women and children, and those with disabilities are overwhelmingly likely to be caught in the negative insecurities of the gig in cottage industries and platforms alike. Further, the standard employment contract norm has historically been made accessible primarily only to men, particularly white men of the Global North.11

Here, we can see how gig work constitutes an insidious biopolitical technology. As Isabelle Lorey argues, the limits placed on access to the Fordist ideal of stable, dignified employment and the family wage reveal how work functions as a patriarchal and racist institutional apparatus of the welfare state.12 The standard employment relationship characterized of Fordism was not meant to provide protection and security to all, but to safeguard a selective portion based on intersectional valuations of life: “to control the precariousness shared among all by striating and positioning dangerous ‘others’ as the precarious ones at the ‘margins.’”13 From this perspective, the security marked in the standard employment relationship is that which makes live—it is a state apparatus that allows for the welfare of a group to be recognized and safeguarded. And gig work in formal and informal markets, constituted as the “outside” of the standard employment relationship, exercises the other facet of the biopolitical equation: it deliberately precaritizes under/unvalued populations through matrices like race, gender, citizenship so that they can be rendered subordinate and docile in relation to valued and protected populations.14

Making Live through the Gig

This study takes on this approach, but instead of examining the necropolitics of gig work, it focuses on the other part of the equation—the capacity to “make live”—to surface different kinds of capital–labor relationships that the gig cultivates. This approach responds, in part, to Alessandro Gandini’s observation that a focus on exploitation cannot fully account for the “ambitious objective of critiquing the relationship between capitalism, work and technology in the 21st century.”15 My suggestion is that the experimentality based around gig work platforms that are unfolding in Singapore needs to be understood through the broader experiments of the gig in the 1970s, which were first envisioned not just to create profit, but as a way to produce a particular kind of life for a specific group of working-class and their families. This was not just aimed to enable life but to create conditions by which life itself could be evaluated and adjusted.

The conception of biopolitics was developed by Foucault through a series of lectures where he spoke on how disciplinary power was complemented by a pastoral exercise of power from the eighteenth-century, delivered through the assignment of institutional resources that could influence the mortality of populations at scale.16 “Bio-power,” Foucault stated, “was without question an indispensable element in the development of capitalism: the latter would not have been possible without the controlled insertion of bodies into the machinery of production and the adjustment of phenomena of population to economic processes.”17 But here, biopolitics desired not only the brute insertion and adjustment of populations to work. Capitalism wants “growth” in control over populations to enhance economic processes: “it had to have methods of power capable of optimizing forces, aptitudes, and life in general without at the same time making them more difficult to govern.”18 “Making live,” or governmentality through the bios, by regularising populations to their environmental milieu, to safeguard their well-being by encouraging particular configurations of life, stood here as the new mechanism of governance and subjectivization.19

Taxi-driving in 1970s Singapore provides a striking example of how gig work can incorporate such biopolitics. This essay unpacks this by focusing on one Singaporean taxi company—NTUC Workers’ Co-operative Commonwealth for Transport (abbreviated as Comfort, later ComfortDelGro)—which was and remains one of the largest taxi companies in Singapore and the world.20 Starting in 1970, Comfort had invested its operations with a powerful vision of the transformative potentials of taxi-driving labor. Examining the biopolitics of this case allows us to consider how gig work can contribute to the construction of new population that could open possibilities of experimentation with the bios at its rawest: a hope for control over not only over workers (to make them hardworking and cooperative), but also over their family and the reproductive stock of the nation.

Comfort’s coincidence with the global spread of neoliberal governmentality in the 1970s makes this case all the more interesting.21 As Veena Dubal documents, the legal category of the “independent contractor” which underpins the gig ascended in the United States during the 1970s, driven by neoliberal ideologies. Courts in America at that time had mapped the figure of the “entrepreneur” onto the “independent contractor,” using the former to rationalize the latter. While this move was partly driven by a pragmatic response to changes in employment—by the rise of temping, outworking, and models of leasing—it was also underpinned by a liberal, pro-business rhetoric of freedom and efficiency. Workers “free” from the chains of employment were said to be more independent, efficient, and capable of entrepreneurially seizing opportunities in the “free market.”22 Argued this way, “risk and uncertainty are interpreted as the workers’ entrepreneurial opportunity and potential,” and the legal status of “independent contractor” ironically became a right to entrepreneurship that must be protected from employment.23 The influence of this argument can be witnessed in the taxi occupation in San Francisco and New York, which changed from employees to independent contractors after the 1970s. The gig, in this case, can be understood not as an objective category of work and workers, but as a socially constructed legal category that is produced through an intersection of business models, ideologies of work, and power dynamics between unions, companies, and government.

But while decades of Keynesian and welfare protections were undone in America, a different experimental model of the gig was taking place in Singapore. Like in America, a new cohort of Comfort taxi workers were understood as independent contractors, owning, at least in theory, the freedom of when and how much to work. However, unlike in the United States, the primary figure that guided this new impression of the gig was not the “entrepreneur” but the “family man,” a responsible man with a strong work ethic, who seeks to work hard not for himself but to enhance the potentials of his children. Taxi-work was understood here as gift and bargain: workers were promised uplift and entry into the rapid upward economic and social progression experienced by the country from the 1970s, but they had to, in return, transform themselves into ideal working-class family men.24

Returning to the question posed at the beginning—what is gig work meant to do—Comfort’s effort at “making live” involves not only the enablement of a particular population; it directs attention towards the milieu of what life and flourishing means and the concessions it demands. We analyze these terms to complicate existing discussions on gig labor, to highlight how the gig can function as a cultural institution, determining not only norms of work or experiences of precarity, but the hopes, values and practices of workers. “Workers’ interests are socially constructed and an outcome of distinct struggles informed by the times, places and scales at which they take place,” Hannah Johnston and Susanne Pernicka write.25 We suggest that Comfort taxis have played an important role in shaping a cultural narrative of what the gig can and should do—which remains relevant to understandings of the gig in Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Method

The historical portion of this essay, covering 1970 to 1993, relies on a heterogenous mix of materials. Comfort’s corporate magazine, Comfort News (CN), the primary internal communication tool employed by Comfort managers, provides a rich understanding of the company’s initiatives and rationales. The extensive collection of Comfort anniversary booklets supplemented these documents. We also drew heavily from news articles sourced from microfilms and digital archives. Most articles came from the Straits Times (ST), the newspaper with the largest readership in the country. Oral interviews, speeches, parliamentary proceedings, and theses amassed by the National Archives of Singapore and the library of the National University of Singapore triangulated the themes found in the news articles and corporate periodicals.

Our analysis focuses on the complexities involved in transforming the gig work of taxi-driving. In this regard, some background information had to be left out. For instance, Comfort and its links to the trade union is beyond the scope of this paper to elaborate at length; we offer only a simplified account to contextualize Comfort’s emergence. Further, we use the pronoun “he” to describe the generic taxi-driver. This is a deliberate choice. Almost all—if not all—Comfort drivers in the early years were married men.26 Gendering the occupation is a way of making clear that the effort of enabling life follows patriarchal and heteronormative norms.

Against other written histories, including the formal historical rendition of Singapore’s taxi industry,27 hagiographies emphasizing the Comfort’s role in providing jobs to thousands of drivers,28 and genealogies of gig work, centred on precariousness,29 we focus our narrative on the compromises involved in the gig’s capacity to make live, emphasizing the complex, mutable ways by which biopower can play out through precarious circumstances of labor.

Disruption: Pirate Taxis and the Arrival of Comfort

The emergence of Comfort must be understood in the backdrop of the late 1960s as the newly independent nation-state was ramping up efforts at modernization. Prior to the arrival of Comfort, Singapore was serviced by two major modes of taxi transportation. First, the country had about 3,800 licensed but disorganized taxi drivers.30 Second, this group was supplemented by a large grey market of an estimated 7,000 “pirate” drivers who drove illegally without licenses.31 Most pirate drivers rented diesel vehicles from taxi barons and went around plying in a car-pooling fashion, picking multiple passengers along the same route. Though illegal, pirate taxis were cheaper, more convenient, and covered a wider service area, making them an essential part of the everyday transportation.32

A dramatic shift was to take place in 1970, however, when a report submitted by Transport Advisory Board recommended the eradication of pirate taxis. Charging pirate taxis for contributing to the “traffic snarls and jams” in the city, the Board warned that “millions of dollars of public funds” invested into “major road development” could be nullified if this grey industry is not curbed.33 The infrastructural problem was then mapped onto a labor problem. “‘Pirate’ activities,” the report continues, “are not consistent with the Republic’s aim of building a law abiding, disciplined, tightly knit and organized society for Singapore.”34

With this, the clampdown on pirate taxis began in earnest. In what is likely the most intense instance of “disruption” in the taxi industry of Singapore, the traffic police began arresting pirate taxi drivers en-masse, at one point nabbing a thousand drivers in a day, leading to the almost complete eradication of the pirate taxi industry by July 1971.35 This clampdown operation is significant not only because of its effectiveness and scale. In his reflection, Leslie Wong, who headed the traffic police operations, described the arrests as a “very unpleasant job.” The punishments levied on pirate taxis were, in his view, “very harsh,” especially considering pirate taxis were more of a “social” problem than a criminal one.36 Those caught driving pirate taxis would be fined and have their vehicles confiscated, which would amount to a significant financial loss that could drive the drivers into debt. Wong even recalls pirate drivers bringing their wives and children to beg for mercy, stating that the arrests could destroy their families. “We are not a public nuisance,” pleaded a driver in a newspaper, explaining that there are many who are unable to take buses or licensed taxis, who pirate taxis service.37

This context is important because it highlights what the orchestrated arrival of Comfort was meant to do. During parliamentary sessions, the Minister of Communication acknowledged that pirate taxis were “providing an element of public transportation service” but their status of illegality was “harmful to the long-term planning of an improved transport service.”38 Comfort was its solution. In the initial years, Comfort especially focused on absorbing former pirate taxi operators into the company, seeking to transform former illegal workers into an organized, disciplined workforce which could represent the progressivism of Singapore’s economic aspirations.

For this reason, it is fitting that Comfort was described as a “rehabilitation project” from the start.39 Comfort was one of the first workers’ co-operatives set up by the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC), a large trade union which was making an important shift in identity in the late 1960s.40 As Soon Boon Chew writes, the problem of unemployment faced after Singapore’s independence in 1965 necessitated a change in NTUC’s purpose “from a wage-negotiating unit to a nation-building institution.”41 The Minister of Labor, Sinnathamby Rajaratnam explained in a 1969 landmark seminar that the “trade unionist had to be militant” under the colonial regime to combat the injustices exercised by the colonial government.42 However, the entangled interests of workers and the postcolonial state meant that modern unionist had to attend to issues of “national interest” and “national economy” instead.43 The battle no longer centered on “a life and death struggle between saintly workers and wicked employers” but issues of “modernization and economic development” which required collaboration between “government, entrepreneurs and workers” that forms the longstanding framework of tripartitism that remains today.44

Comfort, as such, was not simply set out to replace and legalize the profession of pirate taxis. Rather, it was an experiment into a new biopolitical model of work: this was a co-operative operating under the umbrella of a new-era labor union that is linked to the government and meant to foster harmonious relations between the government, business, and workers. As Chengara Veetil Devan Nair, the Secretary-General of NTUC, explained, Comfort was created “with the aim of providing a stake in society to taxi-drivers and pirate taxi operators,” a group that had previously “no stake at all.”45 This notion of work-as-work, work as merely a means of making a living, was deemed insufficient from the viewpoint of NTUC leaders. Comfort was an experiment into a new labor contract: Comfort taxi-drivers would continue to continue to be self-employed gig workers, but their welfare was promised to be protected by the organization.

Whether driven by the eradication of pirate taxis, or the promises of Comfort, the organization turned out to be a tremendous success. The initial ballot for close to 1,000 Comfort taxis held in January 1971 attracted about 3,700 applicants until the decision was made to restrict it to married men aged 21–45, which reduced the eligible applicants to 2,000.46 And Comfort would only grow from there, becoming the world’s largest taxi organization by 1986 with a fleet of 6,500.47

Making Live and Disciplinary Compromises

Comfort’s entry had a dramatic impact in changing the perception of the taxi gig. As example, three years after Comfort began operations, the newspaper raised Mr. Choo as an exemplar of the success that Comfort had “in rehabilitating former ‘pirate’ taxi operators.”48 Recalling his insecure livelihood in the past, Choo remarked on how he was subject to the whims of taxi barons who could raise or terminate his rental at will. Comfort marked a dramatic transformation. “More important than actual earnings,” he explained, “is that my livelihood is secure, my income regular and my future stable.”49 Regularity, stability, and security—these terms stand in stark contrast to the precarious ways gig work is understood today. But there was a concerted effort at this historical juncture to protect taxi drivers, even to imbue the occupation with a quality of what the chairman of Comfort describes as a “career,” something that drivers can be “fully committed to.50”

This possibility hung on middle-classed traits of proprietorship and acquisition, framed through a philosophy of “cooperative welfarism.”51 Up until Comfort’s corporatization in 1993, taxi operators could become owners of their vehicles after paying off their car’s installments. Unionist Thomas Harold Elliott explained that ownership fostered pride, skill, and earning potential: owners would take greater care of their vehicles, have the incentive to improve on their service, and receive a larger income over time once installments and rents end.52 Further, schemes by Comfort, like the compulsory saving scheme, would assist drivers towards accumulating savings for a new vehicle or home. These schemes were paternalistic in that they enforced habits of savings and thrift. But such paternalism also attached the working-class men to imaginaries centered around uplift and the good life—a vision of class mobility ensured through devotion to labor.

However, this is not to say that the transition to Comfort was all rosy. The taxi-gig was especially subject to major disruptive changes over the two decades. In April 1985, for instance, drivers were subject to an “island-wide taxi boycott” when the government enforced a doubling of taxi fares, which led to months of nearly negligible incomes.53 Policies imposed, like the diesel tax and certificates of ownership, also added significantly to the costs of operation, creating dramatic fluctuations in the income of drivers.54 The hours of work would have to steadily increase to keep pace with these costs. A driver noted that he needed only to drive eight hours a day to feed his family of four in 1983. A decade later, he needed to drive ten.55

Arguably, however, the most difficult challenge laid in the process of self-transformation that Comfort required. At an awards ceremony in 1979, the Minister of Communications, Ong Teng Cheong, remarked that taxi drivers had undergone a dramatic “metamorphosis” over the years.56 While drivers of the past likely wore “a singlet and scruffy pants with slippers,” Ong said, the driver of today is an “English-speaking well attired cabbie, who drives his own impeccable air-conditioned vehicle.”57 This illustration speaks directly to the kind of uplift and improvement that Comfort exacted.

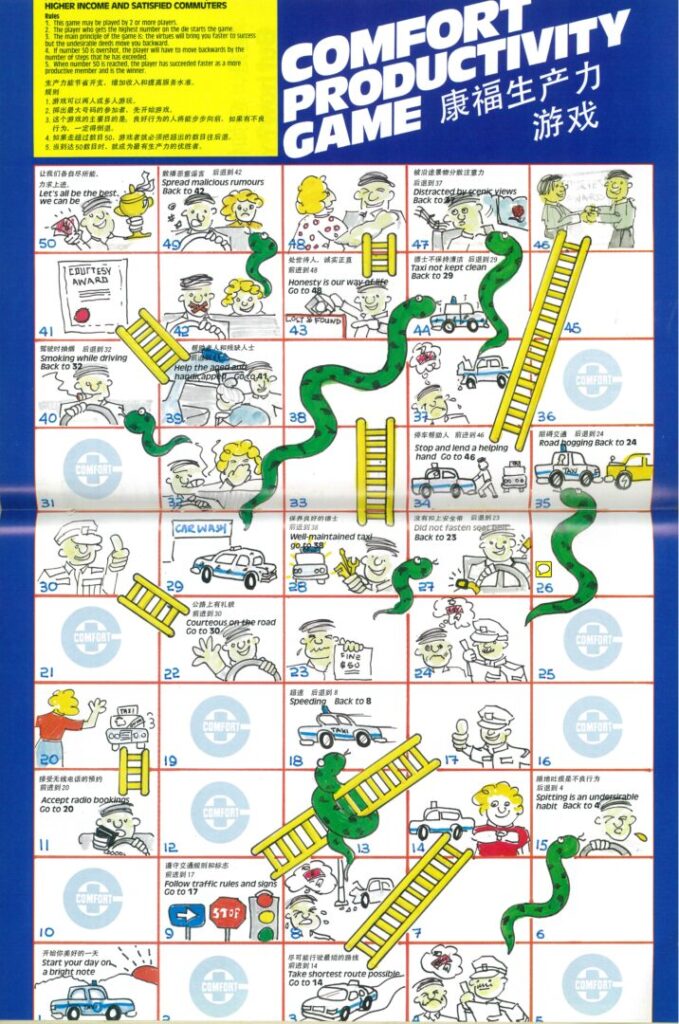

The “Comfort Productivity Game,” packaged with a 1985 issue of CN, provides a sense of the behaviors expected (fig. 2). Drivers were tasked to be courteous, accept radio bookings, avoid spitting, and to refrain from smoking while on the road. These behaviors are then subject to surveillance and enforced through merits and demerits. On a day-to-day basis, drivers can be booked, reported, and have their license suspended or revoked for not picking up passengers at the front of a taxi stop; parking and gambling at racecourses; and for speaking negatively of the co-operative and the Singapore government.58 These measures attracted controversy, prompting letters asking if personal choices for leisure should come under monitoring and if it is appropriate to curtail the rights to speech.59 But the measures continued regardless, deemed a requirement for professionalization.

This demand for improvement is primarily rationalized through an ideology of nationalism. At a taxi kiosk opening in 1982, Comfort’s general manager reminded drivers that they are a part of the national “labor movement.” And so, unlike the “ill-disciplined and disorganized” pirate taxi operators of the past, Comfort drivers should aspire to be a “well-organized, disciplined labor force.”61 Though “self-employed” and presumably “free,” drivers still had the social responsibility to “be well disciplined in their personal life as well as in the rendering of the services to the public.”62

All these expectations and disciplinary measures relate to the discourse of “weeding out.” Used to suggest that only a “small minority” of “black sheep” were harming the interests of Comfort drivers, the threat of “weeding out”—a revocation of licenses—was wielded to demand discipline of Comfort gig drivers.63 Enforcement of this came from different angles. In the 1970s, commuters were encouraged to write to Comfort to report unsatisfactory service, and traffic police were tasked to catch misdemeanors by taxi drivers.64 By the 1980s, Comfort would use data from taxi meters, driving records, and accident reports, to determine if licenses and vehicles would be renewed.65 Drivers were also solicited into this process. When a news agency published reports of “poor work attitudes” among drivers,66 Ong urged operators to identify the “black sheep in their midst,” offering merit points to those willing to inform on them.67 “No one is forcing you to drive a taxi,” Ong chided, “If you can find a better job, good luck to you.”68

The warning at the end indicates the disposability of the drivers, implying that Comfort is the last chance for these men to come into the fold of national progression. As previously mentioned, the biopower exercised by Comfort does not follow a straightforward process of “making live”—the promise of protection was coupled with expectations that reveals an ambivalent scene of what “progression” meant, even if one were enfolded into it.69 Most prominently here, protection was never used to displace the precariousness of the gig itself. In fact, to render the gig “productive,” capable of transforming working-class men, these drivers must be reminded of their proximity to a state of abandonment, their lack of worth in the marketplace and the ease by which they can be disposed. In this way, taxi drivers were coerced to internalize the standards expected of the co-operative, with the object of “security” being the stake of their assimilation.

Social Reproduction and the Whole Man

Who stands to benefit from Comfort’s initiatives? In this section, we pivot from the experiences of the gig to chart the imaginary of progression forged around taxi-driving. Although drivers were the clearest target of improvement, the transformation of their work ethic was assumed to have broader repercussions. Most prominently, the improvements to the taxi-man is envisioned to flow into a normative nuclear family: from patriarchal head, to wives who have finances to care for children, and then to the children who take on the values of hard work cultivated in their fathers. From there, hardworking children are expected to have the will to pull their families out of their working-class statuses, establishing the virtuous cycle of “hard work” itself. As a previous employee at Comfort, Tan How Ing explained, Comfort held on the premise that the “destiny” of the family will change “if their children are doing well through their education.”70 And the success of this vision, Tan suggests, can be seen in the many children that have entered the university.

From this perspective, core to taxi-gig is an attempt to engineer the social reproductive processes of working-class families: to protect families to preserve and hone their multi-generational potential in advancing the family and nation-state. When looking into social reproduction, most scholars have focused on the unwaged, invisible labour of the home—usually done by a woman—that grounds and subsidizes waged work and capitalist processes of production. The patriarchal norm of the male “family wage” in this case is often wielded as a source of power, a means by which the man gains control over family members.71 We see this enacted clearly with Comfort. Most reports on Comfort drivers suggest that the wives of drivers were housewives, and when Comfort started an initiative to have wives act as relief drivers while their husbands were resting, the drivers interviewed expressed reluctance to have their wives work. “If my wife becomes a taxi driver, who is going to bring up the children and look after my house? A house without a housewife will be chaotic,” a driver responded.72

Contained within the biopolitics of taxi-driving, as such, is the continued subjugation of women. Women were stopped and discouraged from being drivers (there were 170 men registered as drivers for every one woman in 1988),73 and they also had to partake in what Valeria Pulignano and Glenn Morgan call the “grey zone” of social reproduction, where families of precarious workers would have to adapt quickly to the fluctuations of their breadwinners’ income.74 Due to the nature of their work, for instance, the incidence of accidents that lead to disability, trauma, or death are not rare, and women left as widows or carers have to cope with raising a family under dire circumstances.

Still, the policies of Comfort highlight a politics of social reproduction that extends beyond gender. Here, the hope for class mobility is placed less on the driver himself than his children and the plasticity they represent. Because the taxi-gig is fundamentally understood to be an inferior kind of work for the less-educated, the promise of Comfort is not necessarily there to guarantee significant improvement to the lot of the drivers. Rather, the larger goal is to improve the conditions of the family that could preserve the potential of this populace found through their children. In this sense, though not perfectly aligned with the eugenic legacies of demographic and birth control exercised in the period, Comfort’s multi-generational view of uplift still holds to a particular reproductive position that targets the families of drivers.75

At the most basic, this stance is apparent in the exclusionary standards advanced by the organization. As mentioned, Comfort’s initial ballot in 1970 was restricted to married men, and this criterion would stay an ideal at least until 1984.76 Over the years, questions were raised about this preference in newspapers.77 One letter-writer to the papers, for instance, lamented that “bachelors will find themselves on the dole” if Comfort retains its exclusion of unmarried men.78 But the non-response to these inquiries suggested that the protection of married men is a matter of common sense: the family was to be the key target of Comfort’s protection, not the men. Second, the protection of the family was adopted as an organizing principle for Comfort’s welfarism. This plays out most clearly in the welfare programs targeted at children. Comfort invested heavily in study loans, education awards, and enrichment classes. In 1974, the bursaries and scholarships awarded by Comfort totalled $20,000.79 By 1989, these awards amounted to over $700,000.80

But the ideological fusion of the driver and the family went well beyond a monetary figure. Equally significant is the way that Comfort intervened into the non-work domains of both operators and children. For example, gambling was a popular leisure activity amongst drivers during the period, a predilection that rendered them the largest occupational group of illegal money borrowers.81 Both Comfort and the government had tried to curb this habit. Direct measures employed include a ban from parking at the horse races, the shuttering of taxi kiosks notorious for gambling activities, and an enactment of a moralistic play on gambling.82 More subtly, however, Comfort had sought to fill the leisure time of drivers with “wholesome,” middle-classed activities. Described as being targeted at the “well-being of the whole man,” Comfort organized events like donation drives, hobby gatherings, excursions, and family events throughout the year, encouraging the productive use of leisure time.83

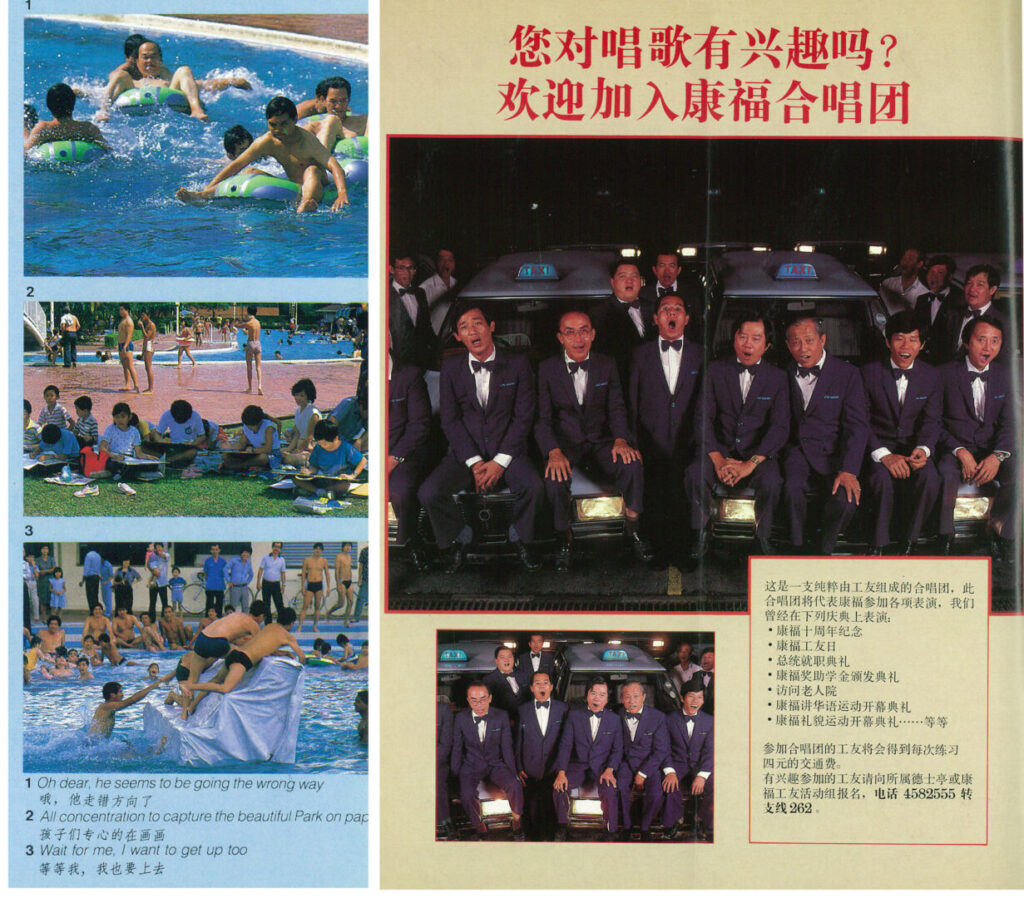

The photographic emphasis on the “family” in many of Comfort’s organized events, represented through CN, shows how the taxi-gig sought to engineer social reproduction not only through the patriarchal norm of the family wage. It had worked in a more thorough way: to school drivers in models of “good” fatherhood. In this model, masculinity is distanced from the antagonistic image of class struggle and attached to a more docile image of the hardworking, honest, responsible family-man. Success lies in providing for children, encouraging their educational attainment, and enabling them to move up the social ladder. Images of men playing with children, and engaging in wholesome hobbies like the choir, illustrates the thorough effort spent to divert working-class masculinity towards that of the family, so that their children can be fully developed in their potential (fig. 3).

This vision was especially reinforced with statistics provided by the Public Service Commission (PSC) in 1979, which noted that 39 percent of recipients of the most prestigious government scholarships over the last decade were children of parents with occupations of the lowest status—manual workers, taxi drivers, and hawkers.86 What is key to progression, explained the spokesperson of PSC, is not the wealth of families but the innate character of children properly nurtured: “a powerful brain, active glands, and the determination to achieve.”87 Speaking to drivers, Devan Nair expressed that the numbers reflect that “equality of opportunity is a fact of life in Singapore.”88

This expectation of protection for upward progression is so strong that drivers were often seen to have failed if their sons were to drive taxis too. During a parliamentary hearing, the spokesperson for a taxi association, Lim Kim Seng, was questioned when he raised his wish for a legislative measure to transfer his taxi license to his children. The committee appeared surprised by the suggestion, asking: “Would you not . . . like to see your children take up a job with better income, better status than continuing your traditional work as taxi driver? In other words, do you not want to see an upward mobility of your future generation?”89 This question is notable for its assumption of Lim’s request. For Lim, the transferability of licenses made perfect sense: his son would have a backup to make a living, and the license could be sold if it could be transferred out. But to the committee, the request seemed to encourage mediocrity. This was a view held of other drivers too. Most answered negatively when asked about an initiative that allowed family members to be relief drivers. One said, “Who wants his children to be a taxi-driver? I am sure every father wants his children to do better than him.”90

However, the investment in generational class mobility obscures how privilege is maintained and reproduced. In fact, the education system was undergoing a significant change in 1979, the same year that PSC released its report. As Michael D. Barr and Zlatko Skrbiš document, the new education policy had formalized a system of ranks and bands, where students were placed into different streams based on academic performance starting at age nine.91 This caused anxiety in parents who worried that their children would be labeled as “failures,” and that anxiety led to an intensification of academic pressure and the normalization of private tuition. Unsurprisingly, this shift disadvantaged working-class families who lacked the time and resources to provide extra coaching. Hence, when evaluating this policy, Barr and Skrbis had described it as “a refined system of elite selection and elite formation.”92 Those who could pour in more resources enabled their children to be streamed into elite schools, which added onto the educational resources they already had. Conversely, the disadvantage compounded for those with less resources and scored poorly. Therefore, contrary to the claim that the “equality of opportunity is a fact of life in Singapore,” class stratification was rapidly accelerating at that historical juncture.93

In Abolish the Family, Sophie Lewis describes the family as an “ideology of work,” stating that “the family is the reason we are supposed to want to go to work, the reason we have to go to work, and the reason we can go to work.”94 We see this ideology of familialism play out with Comfort drivers in a strong sense. Their protection and inclusion into the national narrative is not just founded on their breadwinner’s wage and supported by their families. More significantly, it is the family that rationalizes the value of the gig. The gig work of taxi-driving was important because it allowed for engineering the family. It enabled the social development of children, who were imagined to become the future workers that would bring continuity to the project set out by the state. At a scholarship award ceremony, a spokesperson said: “There has never been any difficulty in obtaining a good job” for those who are diligent in their education. After getting a job, he continued, most people would get married and “within a few years . . . be able to have a government-subsidized flat of their own.”95 The value of the gig came with alignment to the State project of human capital accretion and uplift.

Conclusion

Protected yet precarious, inclusive yet structurally exclusionary—the gig work of taxi-driving was rife with contradictions during this period. Taxi drivers did not only exist in the liminal zones between making live and letting die; they were guided towards seeing an alternative horizon of “better work” that their children should do. Unlike the “exploitation paradigm,” the taxi-gig in Singapore was explicitly designed to enable and foster certain kinds of life—the sort that would be included in an imaginary of national progression.96 But inclusion here did not substantially transform the way the gig is valued. Instead, the gig continued its negative status: it remains a form of work meant to preserve rather than flourish, a last resort for those left out of alternative employment to be enfolded into the Singaporean Dream.

This essay opened at a critical juncture in 2013 when Uber entered Singapore. For a while, the gig was imagined differently: a side hustle for young, single entrepreneurs to get some income while they try to get their business up.97 But as it became clear that ride-hailing platforms were used as an alternative to taxis, the regulations changed. Seven years later, in 2020, the minimum age of the ride-hailing driver was raised to 30—grafted onto the taxi-drivers who have the same minimum age.98 The new requirements, a spokesperson said, would “encourage young drivers to gain outside work experience that will enlarge their skill sets and provide them with long-term job prospects.”99

This regulation reflects the legacy of Comfort. Gig work is still contrasted against the “norm” of a standard employment contract, designed for middle-aged Singaporeans and meant to be taken up as a last resort. Further, the nation and family continue to structure popular imaginations of the gig. During the period of massive COVID-19 unemployment, the platform company Grab released several ad campaigns showcasing workers using gig work as a last resort to support their families. One covered a former flight captain who is praised for having “the courage to start over” to be a driver when flights were grounded.100 Another showed food delivery workers working and supporting their families, after being retrenched during the pandemic.101 The 2022 National Day celebration even featured a Grab food courier as the national symbol of an essential worker (fig. 4).102 In this way, the gig continues to simultaneously normalize and marginalize—it is acknowledged as part of our social and economic landscape, a source for the social reproduction of families, but insisted as a last resort and an inferior form of work.

If the past remains with us, we can also use it to critically evaluate the present. In the present, platforms like Grab have presented themselves as progressive, advancing welfare policies like accident coverage and paid medical leave as evidence of commitment towards inclusive economic empowerment. But these efforts, in many ways, mark only an impoverished reversion to the experiments taken up on gig work in the 1970s to mid-1990s, where union leaders had put in significant effort to reconsider how gig work can be used to “make live.”103 Though not elaborated here, in my interviews, gig workers have repeatedly described the initiatives—reskilling and accident insurance plans, for example—as confusing as best, and perfunctory and useless at worst. Insufficient effort had been undertaken to seriously build plans that show commitment to the lives of workers. Further, and more problematically, these limited efforts at welfare do not fundamentally change the valuation of the gig. The discrimination against gig work today does not gel with actual changes happening in the economy: gig workers may move from one platform to another, and from task to task, but such kinds of work are likely only to grow and continue being the main kinds of livelihood for many.

And herein lies the conundrum. We have been critical of many of Comfort’s shortcomings. But as an experiment for making live, Comfort did allow many working-class drivers to support themselves and their families and participate in a scheme of national progression. Still, the concessions made in exchange for inclusion cannot be ignored. Much had to be sacrificed to realize the possibility of uplift with Comfort: lives had to be disrupted, men forcefully transformed, and wives relegated to homemakers. The consequences of these concessions may not have been evident in the 1970s and 80s when there was rapid economic growth. But these promises would look frayed by the 2000s, as stagnancy, inequality, and class stratification grew. Here then, we see the most troubling legacies of Comfort. Comfort’s culture of paternalism and the suppression of class consciousness has left gig workers with limited collective bargaining power. So, unlike the ground-up strikes occurring in countries like Australia, Thailand, and the United States, gig work in Singapore has largely continued unhindered despite public concern.104 If workers do continue to work for their families today, it is more a manner of disillusioned survival.105

This is not to say that nothing positive is happening with gig work in the country. Singapore is the first in Asia to introduce new legislation for the protection of gig workers in cases of work injury.106 And there continues to be active interest, as with countries around the world, to remake gig work so that it can be rendered more sustainable. But focusing just on the limited legislative measures misses something important about the nature of gig work itself. If Comfort proved anything, it is that gig work is not just work. Gig work is a cultural institution, a space to reconfigure capital-labour relationships.107 Recall the question that guided this paper: what is gig work meant to do? Like how pirate taxis were enfolded into Comfort’s promise of security and progression, gig work today can be transformed in its value. And as cultural institutions, gig work influences not only the norms and experiences of work; it can be used as grounds for struggle, to embark on the radical reimagination of what work can do for its collectives.

This is a point worth insisting and repeating, lest gig work becomes yet another “problem” to be solved. Yes, it is undeniable that the gig embodies much of the worst problems with precariousness, and it is dangerous to be romantic about the revolutionary possibilities of the gig lest we project our own desires at the expense of the most vulnerable, who have the bear the brunt of the gig’s harms.108 But improvements in work can and should be struggled with for along with a demand for change in how the gig is valued. What is needed is a thorough engagement with the problems and possibilities of the Comfort experiment, and that requires inclusive commitment to the valuation of gig work, to see all lives as worthy of being protected and worthy of flourishing, regardless of the hours that gig workers put in and who the workers are.

Notes

- Uber, “Singapore | Uber Entrepreneur,” YouTube video, June 22, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7WAk0ATUU84. ↩

- Sam Hwang, Cabbies (Singapore: Anthony Ooi, 2017), 10; Adrian Lim, “Must Taxi Uncle Give Way to Uber Driver?” The Straits Times, January 12, 2017. ↩

- As examples see Jeremias Prassl, Humans as a Service (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018); Jamie Woodcock and Mark Graham, The Gig Economy (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2020). ↩

- This article builds off scholarship from the anti-work tradition that supposes work to be more than wages (as examples, see Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy, trans. Francesca Cadel and Giuseppina Mecchia (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext, 2009); Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); Renyi Hong, Passionate Work: Endurance after the Good Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022). The critique of workerism opposes the ways that work is used as a system of economic, social, and political integration. ↩

- Hwang, Cabbies, 10. ↩

- Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-6, ed. Mauro Bertani and Alessandro Fontana, trans. David Macey (New York: Picador, 2003). ↩

- Bingqing Xia, “Rethinking Digital Labour: A Renewed Critique Moving beyond the Exploitation Paradigm,” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 32, no. 3 (2021): 311–21, https://doi.org/10.1177/10353046211038396. ↩

- Matthew W. Finkin, “Beclouded Work, Beclouded Workers in Historical Perspective,” Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal 37 (2016): 603; Michael Quinlan, “The ‘Pre-Invention’ of Precarious Employment: The Changing World of Work in Context,” Economic and Labour Relations Review 23, no. 4 (2012): 3–24, https://doi.org/10.1177/103530461202300402; Woodcock and Graham, Gig Economy. ↩

- Jim Stanford, “The Resurgence of Gig Work: Historical and Theoretical Perspectives,” Economic and Labour Relations Review 28, no. 3 (2017): 382–401, https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304617724303; Veena Dubal, “Digital Piecework,” Dissent 67, no. 4 (2020): 37–44; Woodcock and Graham, The Gig Economy. ↩

- “The development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions, so too did social ideology. As a material force, then, it could be expected that racialism would inevitably permeate the social structures emergent from capitalism.” The term “racial capitalism,” derived from Robinson’s analysis in Black Marxism, has been used to advance arguments centering race as the primary stratifying factor in capitalism’s development. See Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1983). For a development see Susan Koshy, Lisa Marie Cacho, Jodi A. Byrd, and Brian Jordan Jefferson, eds., Colonial Racial Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022); Veena Dubal, “Wage Slave or Entrepreneur?: Contesting the Dualism of Legal Worker Identities,” California Law Review 105, no. 1 (2017): 65–123, https://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z38M84X. ↩

- Jeremias Prassl, Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩

- Isabell Lorey, State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious, trans. Aileen Derieg (London: Verso, 2015). ↩

- Lorey, State of Insecurity, 38–9. ↩

- See especially Peter James Holtum, Elnaz Irannezhad, Greg Marston, and Renuka Mahadevan, “Business or Pleasure? A Comparison of Migrant and Non-Migrant Uber Drivers in Australia,” Work, Employment and Society 36, no. 2 (2022): 290–309, https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211034741; Julietta Hua and Kasturi Ray, “Beyond the Precariat: Race, Gender, and Labor in the Taxi and Uber Economy,” Social Identities 24, no. 2 (2018): 271–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2017.1321721; Will Orr, Kathryn Henne, Ashlin Lee, Jenna Imad Harb, and Franz Carneiro Alphonso, “Necrocapitalism in the Gig Economy: The Case of Platform Food Couriers in Australia,” Antipode 55 (2023): 200–221, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12877; Stephen Walcott, “Victimization and Fear of Crime in the Gig Economy,” Police Foundation, November 2020, 31. ↩

- Alessandro Gandini, “Digital Labour: An Empty Signifier?” Media, Culture & Society 43, no. 2 (2021): 377, https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720948018. ↩

- Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended.” ↩

- Foucault, Society Must be Defended, 140. ↩

- Foucault, Society Must be Defended, 141. ↩

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books, 1990). “Governmentality,” developed from Foucault’s work, is described by Miller and Rose as a means of governing “at a distance.” Governmentality involves the creation of a political language used “not only to articulate and legitimate a diversity of programmes for rectifying problematic areas of economic and social life, but also enabled these programmes to be translated into a range of technologies to administer individuals, groups and sectors in a way that was consonant with prevailing ethical systems and political mentalities.” See Paul Miller and Nikolas Rose, “Governing Economic Life,” Economy and Society 19, no. 1 (1990): 1–31. ↩

- The NTUC Workers’ Co-operative Commonwealth for Transport is abbreviated by other writers as NTUC-COMFORT or COMFORT. For reasons of readability, we have chosen to name the co-op Comfort. ↩

- See as example, Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval, The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society, trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2017). ↩

- Insecurity, as Nickolas Rose explains, serves as the basis for the neoliberal formulation of freedom. Neoliberalism demands the restructuring of security, to “remove as many as possible of the incitements to passivity and dependency; make the residual social support conditional, wherever possible, upon demonstration of the attitudes and aspirations necessary to become an entrepreneur of oneself; incite the will to self-actualize through labour through exhortation on the one hand and sanctions on the other.” Nikolas Rose. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999). ↩

- Dubal, “Wage Slave or Entrepreneur?”, 94. ↩

- As we will elaborate later, Comfort was seen as a way to transform the idea of a working-class male collective. Instead of remaining a union that struggled for rights, the collective would be led by government officials, who would also promise to advance the interests of the collective. ↩

- Hannah Johnston and Susanne Pernicka, “Struggles over the Power and Meaning of Digital Labour Platforms: A Comparison of the Vienna, Berlin, New York and Los Angeles Taxi Markets,” in A Modern Guide to Labor and the Platform Economy, ed. Jan Drahokoupil and Kurt Vandaele (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2021), 310. ↩

- “More Women Cabbies Plying the Roads,” Straits Times, January 5, 1988. ↩

- Ilsa Sharp, The Journey: Singapore’s Land Transport Story (Singapore: SNP International Publishing, 2005); Looi Teik Soon and Choi Chik Cheong, “An Evolving Public Transport Eco-System,” in 50 Years of Transportation in Singapore: Achievements and Challenges, ed. Fwa Tien Fang (Singapore: World Scientific, 2006), 67–144. ↩

- COMFORT, NTUC Comfort’s 20th Anniversary (Singapore, 1990). ↩

- Finkin, “Beclouded Work.” ↩

- Sharp, The Journey. ↩

- Fong, “Days are Really Numbered.” ↩

- Sharp, Journey. ↩

- Transport Advisory Board, Reorganization of the Motor Transport Service of Singapore (Singapore, 1970). ↩

- Transport Advisory Board, Reorganization of the Motor Transport, 23. ↩

- Leslie Fong, “The Days Are Really Numbered for 7,000 Pirate Taxi Drivers,” The Straits Times, April 19, 1970. ↩

- National Archives of Singapore, “Leslie Wong Sze Ying – Oral History Interviews,” posted December 2, 2010, https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/oral_history_interviews/record-details/043af238-1162-11e3-83d5-0050568939ad. ↩

- Fong, “Days Are Really Numbered.” ↩

- Fong, “Days Are Really Numbered,” 10. ↩

- “Aid for Pirate Taximen Plan,” Straits Times, May 29, 1970. ↩

- Though Comfort is a co-operative, the organizational form differs from what co-op generally means today. Comfort drivers have to enroll as members to have a taxi, but their shares were used more as profit-sharing, rather than means to a vote. Generally, most decisions are made by managers. Management would also listen to issues on the ground and bring it to parliamentary discussion. This system is seen as superior in that union leaders, typically being government officials, could have direct access to government policy decisions. Explaining this, Ong, the Secretary-General of NTUC offered that “Singapore could not withstand the trauma of chaotic industrial relations” and that “to a small country like Singapore without national resources, the slightest cold or fever could become a fatal bout of pneumonia.” What Comfort offers is a stated commitment towards improving the quality of lives of workers, and the co-operative and union would function as an intermediary between rank and file, gathering the “pulse and feelings of the ground” and process it to a “strong voice in Parliament.” See Ivan Lim, “NTUC’s on the Right Track, Says Teng Cheong,” Straits Times, May 1, 1986. ↩

- Soon Boon Chew, Trade Unionism in Singapore (Singapore: McGraw-Hill, 1991). ↩

- Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, “The Crucial Role of Trade Unions in the Modernization of Singapore,” in Why Must Labor Go Modern: The NTUC Case for a Modernized Labor Movement, ed. NTUC (Singapore: Stamford College Press, 1970), 25–34. ↩

- Rajaratnam, “Crucial Role of Trade Unions,” 31. ↩

- Rajaratnam, “Crucial Role of Trade Unions,” 31. The success of the tripartite framework is mixed. Historically speaking, it is true that Comfort union leaders have had access to make strong appeals in parliament, offering a good basis for collective bargaining. However, not all appeals have led to the outcomes hoped for. The taxi price hikes of April 1985, for instance, were strongly appealed against but not changed, leading to the taxi boycotts that affected the livelihoods of many drivers. (Taxis were listed as a form of public transportation with the prices controlled by the government). The boycotts were so serious that the government was forced to reverse its decision a month later. See “Cab Fare Saga Won’t Be Forgotten Quickly,” Straits Times, June 2, 1985. What is clear, however, is that Comfort did become more corporatized over time. The increase in the price of vehicle ownership eventually made Comfort a lessor. The promise offered early on—that drivers would own their vehicles after years of driving and would experience a steady increase of incomes—would be taken away. ↩

- Chengara Veetil Devan Nair, “The Evolution of a Work Ethic—a Non-Simplistic Approach,” in Not by Wages Alone: Selected Speeches and Writings of C.V. Devan Nair 1959-1981 (Singapore: Singapore National Trade Union Congress, 1982), 190–99. ↩

- “NTUC Taxi Ballot: The Married Men Get First Go,” Singapore Herald, January 6, 1971. ↩

- “Big Comfort,” Business Times, February 21, 1986, 12. ↩

- William Campbell, “A New Breed of Owner-Driver Cabbies,” Straits Times, May 18, 1974. ↩

- Campbell, “New Breed of Owner-Driver Cabbies,” 12. ↩

- “Plan for the 1980s,” Comfort News 5, no. 4 (1980): 1. ↩

- “A Caring Cooperative,” Comfort News 14, no. 3 (1989): 2. ↩

- NTUC, NTUC Comfort Singapore Anniversary Souvenir (Singapore: Tiger Press, 1973). ↩

- B. J. Fernandes, “It Was an Island-Wide Taxi Boycott,” Business Times, April 4, 1985. ↩

- “Special Report: Mr Lew in Parliament,” Comfort News 14, no. 1 (January 1989): 5. ↩

- Maria Siow and Sharon Snodgrass, “Relief that Taxi Study’s on Hold,” Straits Times, October 16, 1993. ↩

- “Smart Cabbies a Far Cry from the ‘Scruffy’ Past,” Straits Times, August 30, 1979. ↩

- “Smart Cabbies,” 7. ↩

- See “Taxis: ROV Can Be Real Tough,” New Nation, November 28, 1974. ↩

- See Jilted, “Can’t We Cabbies Have Fun Too?” Straits Times, May 29, 1980. ↩

- “Comfort Productivity Game,” Comfort News 10, no. 11 (November 1985): 20. ↩

- “Comfort Operators Are Part of Labor Movement,” Comfort News 7, no. 2 (June 1982): 8. ↩

- “NTUC Comfort Scholarships 1977,” Comfort News 2, no. 6 (December 1977): 2. ↩

- “Impact of the Co-Operative Movement,” Comfort News 2, no. 1 (February 1977): 1–5. ↩

- “Taxis: ROV Can Be Real Tough,” 1. ↩

- “Drivers with Records Not Allowed to Replace Their Scrapped Taxis or Buses,” Comfort News 8, no. 2 (March 1983): 9. ↩

- Chua Ngeng Choo, “Cabbies Have Poor Work Attitudes,” Singapore Monitor, June 15, 1983. ↩

- Rav Dhaliwal, “Look for a New Job,” Straits Times, June 19, 1983. ↩

- Dhaliwal, “Look for a New Job,” 1. ↩

- Foucault, The History of Sexuality. ↩

- National Archives of Singapore, “Leslie Wong Sze Ying – Oral History Interviews,” December 2, 2010. ↩

- Lorey, State of Insecurity. ↩

- Ban Huat Tan, “6,000 Comfort Taxi Owners May Get Green Light,” Straits Times, August 29, 1981. ↩

- “More Women Cabbies Plying the Roads,” Straits Times, January 5, 1988. ↩

- Valeria Pulignano and Glenn Morgan. “The ‘Grey Zone’ at the Interface of Work and Home: Theorizing Adaptations Required by Precarious Work,” Work, Employment and Society 37, no. 1 (February 1, 2023): 257–73. ↩

- Michael D Barr, “Lee Kuan Yew: Race, Culture and Genes,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 29, no. 2 (1999): 145–66. ↩

- It remains unclear as to how the preference for marriage is applied on the ballot for vehicles. In fact, we were unable to locate past policy records that describe the requirements for obtaining a taxi vehicle. This argument is based on official statements found in newspapers. The last found record came from “Qualifying for a Taxi-Driver,” Singapore Monitor, November 30, 1984. ↩

- “Yellow Top Owners: That ARF Cut Is Unfair,” Straits Times, September 7, 1978. ↩

- “Why This Discrimination against Bachelors?,” Straits Times, August 21, 1979. ↩

- “Taxi Operators’ Future in Their Own Hands,” Comfort News 2, no. 2 (April 1977): 3. ↩

- “A Caring Cooperative,” Comfort News 14, no. 3 (March 1989): 2. ↩

- Brendan Pereira, “Taxi Drivers and Hawkers Mostly Like to Owe Money,” The Straits Times, October 23, 1990. ↩

- “‘Race Course’ Cabbies May Lose Licence,” Straits Times, April 30, 1980; “Under-Used, Abused Taxi Stands to Be Removed,” Straits Times, August 30, 1978; “Cabbies to Stage Play with a Moral,” Straits Times, November 20, 1981. ↩

- “Well-Being of the Whole Man,” Comfort News 9, no. 4 (July 1984): 2. ↩

- “Fun and Gaiety under the Sun,” Comfort News 11, no. 2 (February 1986): 9–11. ↩

- “Comfort Choir,” Comfort News 10, no. 9 (September 1985): 22. ↩

- Poteik Chia, “Devan on New Industrial Era,” Straits Times, May 28, 1979. ↩

- “Most Scholars Come from Modest and Poor Homes,” Strait Times, January 1, 1979. ↩

- Chia, “Devan on New Industrial Era,” 1. ↩

- Seventh Parliament Of Singapore, “Report of the Select Committee on Land Transportation Policy,” 1990, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/selectcommittee/selectcommittee/download?id=293&type=report. ↩

- Tan, “6,000 Comfort Taxi Owners May Get Green Light.” ↩

- Michael D. Barr and Zlatko Skrbiš, Constructing Singapore: Elitism, Ethnicity and the Nation-Building Project (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2008). ↩

- Barr and Skrbiš, Constructing Singapore, 122. ↩

- Poteik, “Devan on New Industrial Era.” ↩

- Sophie Lewis, Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation (London: Verso, 2022). ↩

- “Work Harder and Endure Greater Sacrifice to Enjoy Good Living, Pang Advises Students,” Comfort News 7, no. 1 (February 1982): 4. ↩

- Xia, “Rethinking Digital Labour.” ↩

- Uber, “Singapore | Uber Entrepreneur.” ↩

- Tessa Oh, “LTA Sets Minimum Age of 30 for New Private-Hire Driver Licence Applicants,” Today, September 15, 2020, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/lta-sets-minimum-age-30-new-private-hire-driver-licence-applicants-they-must-also-be. ↩

- Oh, “LTA Sets Minimum.” ↩

- Grab Official, “#Remember2020 – from Hardship to Hope,” YouTube video, posted December 18, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ndQUFLlUxGo. ↩

- Grab Official, “The Longest Thank You,” YouTube video, posted June 22, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45tWJ8-vCHk. ↩

- CNA, “NDP 2022,” YouTube video, posted August 9, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gpgpggKhTts. ↩

- Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended.” ↩

- Orr et al., “Necrocapitalism in the Gig Economy”; Thai PBS, “Grab Delivery Service Riders Protest against Allegedly Unfair Rule Changes,” November 3, 2022, https://www.thaipbsworld.com/grab-delivery-service-riders-protest-against-allegedly-unfair-rule-changes/. ↩

- Yufeng Kok, “Delivery, Private-Hire Platform Workers Risk Being Trapped in Poverty, Precarity: Study,” Straits Times, February 28, 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/delivery-private-hire-platform-workers-run-the-risk-of-being-trapped-in-poverty-precarity-study. ↩

- Han Yan Goh, “New Network to Develop Work Injury Compensation Policies for Platform Workers,” Straits Times, February 3, 2023, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/new-network-to-develop-work-injury-compensation-policies-for-platform-workers. ↩

- Gandini, “Digital Labour.” ↩

- Hua and Rey, “Beyond the Precariat.” ↩