Aesthetics, Affect, Politics

In late November 2022, a surge of protests emerged across mainland China, against the draconian quarantine measures against COVID-19. These cases of civil uprising were dubbed the “A4 Revolution” or “White Paper Revolution” because people took to the street with conspicuous homemade signage—pieces of plain white paper, cardboard boxes with hastily composed writings, and iconographies of past revolutions—to convey their democratic messages. Through an analysis of these visual messages, I work toward a critical imagination of democratic potential in an authoritarian state. I aim to map out and reflect on how the historical, political, and cultural memories from the past inform the voices of the present. I theorize aesthetics as a distinctive memory medium and mobilizing strategy, one that is able to (re)present visions of the past and, more importantly, afford a language of dissent that otherwise would be unspeakable. As I will show shortly, the 2022 protest is culturally, semiotically, and affectively conditioned by the thoughts, feelings, and images that were previously approved, or even promoted, by the Chinese party-state. These literary and visual signs co-opt and recontextualize a unique Chinese cultural memory and political landscape that can strategically bypass immediate state censorship and facilitate progressive alliances that transcend generation and class.

Theoretically, I borrow Jacques Rancière’s conception that aesthetic dimensions are central to democratic projects.1 The aesthetic dimension constitutes the system of appearances and utterances that make up the political community. This is what he calls the “distribution of the sensible”—the organization of visibility and sayability within the social order, or police order. In other words, for Rancière, the notion of “the police” is the systems of organization that establish certain regimes of legibility and calibrate the distribution of bodies, roles, and speech acts that make up the consensual frames of perception within a political community. Meanwhile, demos exists in opposition to the police, disrupts the distribution of the sensible, creates confrontational dissensus, and embodies the essence of democratic politics. Dissensus is, for Rancière, an aesthetically rooted political process that both disfigures and reconfigures the perceptual consensus of the social order. As he puts it, “Political activity is whatever shifts a body from the place assigned to it or changes a place’s destination. It makes visible what had no business being seen, and makes heard a discourse where once there was only a place for noise.”2

What Rancière’s theory does not substantively engage with, however, is the affective dynamics and process that actually evoke disruption. Affect, as Gilles Deleuze reminds us, is a preconceptual intensity that acts as a force that animates potentialities between bodies across multiple social and institutional territories.3 Informed by Deleuze, John Flatley concurs that artistic experience, such as literary imagery, is a site where affects become rearticulated and recontextualized in a disruptive way.4 This incorporation of artistic experience and its affective potential has been taken up by Stephen Duncombe. Duncombe identifies an “artful” turn in democratic protest over the past two decades, a move away from the “march and rally” model. Protests, he observes, take on the look and feel of “celebratory carnivals with costumes, props, and performances” as a response to the global neoliberal hegemonic.5 Inspired by his provocation, in this study, I explore how authoritarianism, like the global neoliberal hegemonic, relies on systems of meaning, comprehension, and legitimation. Therefore, it is sustained and, most importantly, could be dismantled by the flow of culture, images, signs, and symbols. Contemporary protests address this reality by using a corresponding strategy that employs mediated images of dissent to reveal injustice. These artful strategies prove to be particularly valuable within communication networks to affectively reach a broad audience. As the next sections will address, protesters of the 2022 movement are particularly invested in visually presenting their dissent via a certain look of their signage.

Furthermore, besides the artful dimension of the A4 Revolution, the movement introduces an additional layer to the protest’s literary imagery, signs, and symbols: historical citation. In the wave of uprising, specific strategies were used to co-opt images and materials deemed permissible by the state. The commonly seen signage of the movement—anti-imperial writings, images of the Cultural Revolution, and a piece of white paper—are all technically part of Chinese people’s routine repertoire; some are even endorsed by the state as important lessons of history. However, A4 protesters are able to repurpose and recontextualize this cultural imagery toward revolutionary ends in the twenty-first century. As Walter Benjamin reminds us, materialist historiography “does not choose its objects arbitrarily. It does not fasten on them but rather springs them loose from the order of succession. Its provisions are more extensive, its occurrences more essential.”6 From this perspective, the uses of the visual and textual signs of the movement precisely show that historical citation, as a method, disentangles the historical object from its contextual constraints, rendering it legible and accessible to a wider audience for a new purpose. Historical imagery and memories are freed from their original context in order to facilitate reinterpretation but are also reconstructed as elements that are comprehensible to a broader audience. In undemocratic environments like today’s China, where accessibility to historical narratives may be limited or controlled by the state, the strategic use of historical citation in the A4 Revolution becomes a powerful tool for mobilizing the masses, fostering emotional resonance, and carrying political significance.

Repurposing historical and cultural memories is politically significant, particularly in a Chinese context. Contemporary interpretations of historical events are shaped by conceptual and rhetorical frameworks that are inherently tied to the interests of specific groups.7 The strategy to selectively omit, decontextualize, or distort past occurrences becomes particularly pronounced when the legitimacy of a regime or the pride of a nation is perceived to be at stake. The Chinese historical narrative is said to be particularly involved in this project because of its association with authoritarianism, conventionality, cognitive rigidity, deference to authority, and traditionalism.8 Zhang and Schwartz point to the state’s “critical inheritance” practice by studying the state’s framing of Confucius.9 They argue that the state opens Confucius for reinterpretation without a wholesale acceptance of his doctrine; instead, his image is constantly recontextualized according to the state’s agenda at a given time. These studies of historical citation and collective memory, however, are all concerned with the top-down ideological projects imposed by the authoritative state. There is a significant gap in understanding “critical inheritance” from the bottom up. What national visual cultural references are mobilized in contemporary protests? What affective functions do these historical visual references serve in the movement, arrangement, and distribution of the sensible? How do people repurpose specific cultural idiosyncrasies to voice political dissent? And how do these references contribute to local political meaning‐making and community-making? The A4 Revolution is a case that participated in the critical inheritance from the bottom up, challenging and countering conceptualizations of the “official” uses of images and memories from the past.

Lastly, in examining the affective process’s disruptive innerworkings in the anti-zero-COVID policy protest, I am mindful that relations are to be carefully mapped out within their historical and cultural specificity. Many scholars have extensively studied the Chinese party-state’s crackdown on democratic protests and extreme surveillance on ordinary people and activists alike, especially in the digital age.10 Despite some scholars’ praise of the Chinese party-state’s ability to adapt and respond to complex social contradictions,11 being an activist in China means not only to voice dissent, but to take on the risk of long-term imprisonment, physical and psychological torture, and being made to “disappear.”12 Because of this, Chinese activists have been tasked with getting their message across while bypassing censorship and avoiding persecution, a “strategic protest.” Deliberate framing, linguistic, and visual strategies are used to adjust contentious discourse, in order to protect the participants, preserve the movement, and achieve large-scale mobilization.13 The A4 Revolution, as I will demonstrate below, embodies a unique mix of an “artful protest” and a “strategic protest” to maximize the affective capacity of the visual and to protect the momentum of the movement. These practices were intentional and self-reflexive attempts to bypass and even mock the biopolitical authoritarian regime.

The A4 Revolution

In the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in August 2020, conservative commentator and writer Hu Xijin suggested that the Uyghur region in China should be subject to more draconian quarantine regulations than others because of its history of East Turkestan dissent: “All cadres and masses in Xinjiang are paying the price for the struggle against terrorism, and they deserve the respect of mainlanders for this. Currently, it is difficult for Xinjiang to calculate the risks of COVID-19 calmly and meticulously like the mainland. The approach may seem a bit “extensive/rough” (cu fang) to outsiders. I think from a macro perspective, this is a sacrifice Xinjiang must make to contribute to the overall nation.”14 Although he does not explicitly explain the connection between historical Uyghur dissent and deserved more heavy-handed COVID-19 prevention measures, Hu ends his piece by promising that according to the experience of the mainland, the pandemic and the days of suffering in Xinjiang are coming to an end.15 However, his prediction of the imminent expiration of Xinjiang’s sacrifice did not come true. China’s so-called “zero-COVID policy,” in which whenever there is a positive COVID case, an epidemiological investigation is carried out to identify and isolate all persons who may have been in contact with the patient, persisted until early 2023.

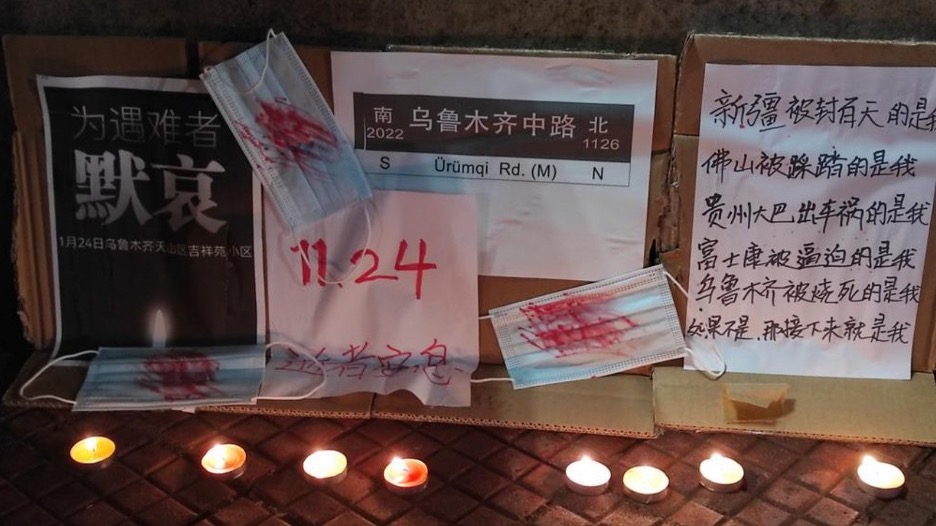

Under this draconian regulation, on November 26, 2022, a fire in an apartment building in China’s Xinjiang region killed 10 people and injured nine. The fire broke out in Jixiangyuan Community in the Tianshan District of Urumqi. Although the authority denies any correlation between the fire and COVID-19 quarantine measures, the tragedy ignited a wave of public outcry as many residents in the area were forced to stay inside their apartment buildings. Screenshots of online chat records among the residents showed that the community had a positive COVID case during one of the routine test samplings, and thus was subject to “fenced-in” quarantine measures. Residents of the community were forbidden from leaving their apartment buildings, with the front doors sealed by governmental orders. There have been speculations that the barricade was what caused the three-hour-long delay in putting out the fire, since fire trucks could only spray water remotely.16 China’s Zero COVID Policy, at that moment, had been ongoing for nearly three years. Many stories of police brutality, mass confinement, and animal cruelty have been reported.17 Just a little over a month ago on October 13, 2022, during the twentieth People’s Congress, protester Peng Lifa was arrested soon after he hung two banners protesting Xi Jinping’s COVID policy and authoritarian rule on Sitong Bridge in Beijing. However, his protest did not attract much attention within mainland China as it was quickly silenced.

On the last weekend of November, however, an unexpected “A4 Revolution” swept across China and gained widespread attention after the tragic fire. It started with the online circulation of a picture of a young college student holding a blank sheet of paper at Nanjing Communication University, which was quickly echoed by students from many universities to mourn the victims in Xinjiang and protest Xi’s COVID policy. On November 27, citizens across the country joined the protests, breaking through the blockade and taking to the streets. Residents of different cities gathered on Urumqi Road (in China, streets are named after major cities in the nation. Many cities have a Urumqi Road) to mourn the victims and demonstrate their dissent.

The visual moments of dissensus represented in the A4 revolution serve as an instance for understanding the distribution of the sensible within contemporary Chinese politics. These moments are not only demonstrative of dissensus within authoritarian orders of perception, but also the strategic and affective elements of dissensus rooted in Chinese political history and cultural memory. Aesthetic and affective function becomes a central concern of my project: how it looks, how it will be reproduced and distributed, and what sort of emotional resonance it will provoke. Through a qualitative analysis of such signs, I identify three loosely defined and sometimes overlapping types of cultural resources co‐opted in the protests in order to provoke affective reactions: 1) motivational slogans and symbols from the Cultural Revolution 2) literature from anti-imperial times, and 3) contemporary techniques to mock and bypass state censorship.

Dazibao

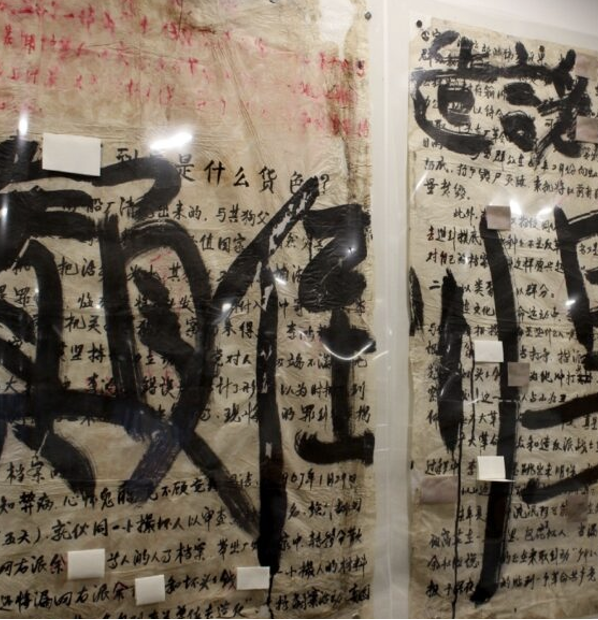

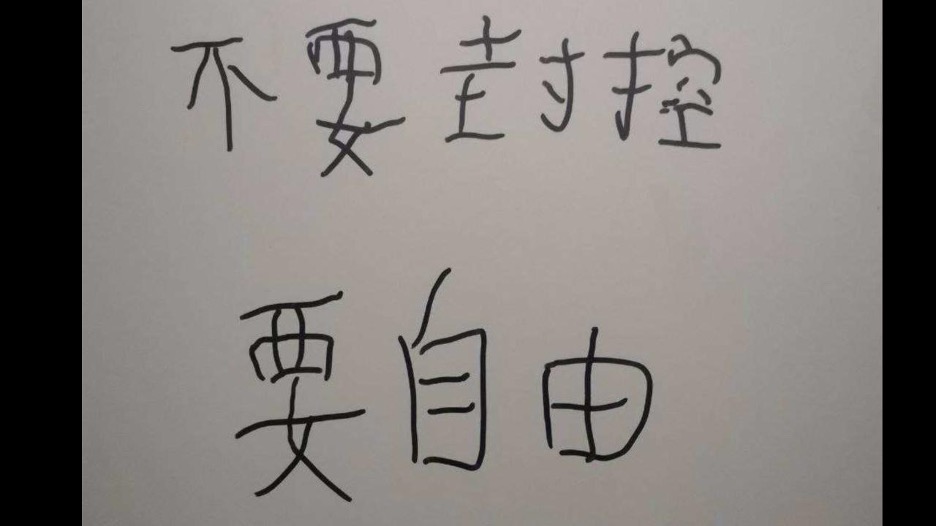

The first type of affective visual sign used in the protests was hand-written or hand-painted red or black lettering over a large piece of white canvas. The font of the lettering is childlike, with bold strokes usually laid out in an unprepared manner. The characters on the sign are written as if the writers are in a hurry: they are not uniform in terms of size, often smeared in many places, and not aesthetically pleasing (see Figure 1). These large, striking signs with blood-like letterings resemble greatly the “Big Character Poster” (Dazibao, 大字报) during the Cultural Revolution era. The big character posters were prominently displayed handwritten posters containing complaints about government officials or policies during the 1950s and 1960s. Dazibao functions as a public spectacle, suggesting a failed leadership and a disillusioned community.18 According to scholarship on Dazibao, the changes brought about by the development of big character posters not only added new forms to socialist democracy, but also served as a powerful weapon for the self-education of the masses.19

Dazibao, written in the form of a wall poster, creates not a private space, but a democratically open, public space for criticism. Although Dazibao may incorporate poetry, comics, etc., its reception and aesthetic cannot be equated with highbrow literature and art. Traditional Chinese art and calligraphy are distinguished by their emphasis on the elasticity of time and space. These artistic forms often require viewing from multiple angles to convey a consistently engaging experience. The technique of liubai or “leaving white space” is a crucial hallmark of canonical Chinese artistic practice. This technique aims to harmonize the composition of the artwork, preventing it from feeling overly crowded and reducing a sense of visual overwhelm. Liubai naturally guides the viewer’s gaze toward the subject, demonstrating intentional planning of space on the canvas as a primary form of expression.

The Dazibao aesthetic stands in direct contrast to canonical Chinese art. Because it relies primarily on the viewing public’s living space, the main objective of Dazibao is to attract attention and be easily readable. This led the Dazibao aesthetic to be inherently counter elitist. The appearance of Dazibao posters often incorporates bold strokes, inconsistent character sizes, and simple and even child-like fonts. The disorder, the appearance of being hastily written, and the conveyance of intense emotional states suggest a deliberate departure from established norms or dominant cultural and political canons. By rejecting the conventional norms of visual communication, Dazibao posters challenge prevailing elitist ideologies, making them a powerful tool for popular dissent and alternative expressions. This project, eliciting emotions and purposefully resonating with the masses, was one of the key foundations of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) successful mobilization of the masses.20 Practices such as “speaking bitterness” (suku)—publicly displaying one’s grievances to elicit empathy towards the speaker and anger towards those responsible for their hardship—are examples of how affective energy can be harnessed to political ends. As such, Dazibao provides a sensory and affective form of communication with the public through excess.

The 2022 protesters’ citation in the contemporary time of Dazibao aesthetic, a form previously used to solidify the authoritarian state’s rule, is a strategic citation of deeply embedded Chinese cultural memory, and one that is self-reflexive—a critical inheritance from the bottom up. The image of the hastily written, poorly organized characters functions at an iconographical level as it only involves a basic cultural knowledge to recognize the image. No matter the reader’s age, class, ethnicity, or gender, they are able to immediately identify this visual as a Dazibao, a form of public political writing associated with the Cultural Revolution. The use of Dazibao-esque aesthetic invokes the cultural memory of a chaotic and disorderly period in Chinese history. In this sense, the Dazibao aesthetic creates a mode of engagement that is extratextual and immediate, one that does not require close reading or mature literary and artistic taste; instead, it is designed to directly spur affect and compel instant judgment. It disrupts the orderly aesthetic of twenty-first-century China (see Figure 2) and offers a sense of democratically created disorder and chaos. The A4 Revolution strategically appropriates Dazibao aesthetics’ affective capacity and visual immediacy: upon viewing, the masses across educational backgrounds are able to realize the message and derive feelings and affects generated by the sensorial stimuli.

Besides Dazibao’s ability to provoke empathetic emotions from its viewers, it is also important to note that Dazibao was specifically born and widely used during the Cultural Revolution, a time of socialist fervor, class warfare, wrongful imprisonment, and nationwide poverty. Dazibao was initially meant to serve as a means of protest against governmental incompetence or corruption. The state used this technique as a way of soothing public dissent and thus stabilizing its rule. However, in practice, it became a way of persecuting the “political right” or the bourgeois and intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution, a time characterized by chaos, violence, and trauma. The legacy and memory of the revolutionary time largely reside in photographic images and other visual means, as the chaos and personal trauma were only experienced by people born before the 1960s. The political past is less a matter of experienced social reality but is important because of the affective impact it has on people via visual references: the iconography and aesthetic of the red classics—Mao’s portrait, the Red Army’s uniforms, and big character posters (see Figures 3–8). The disruptive quality of Dazibao aesthetic at the moment of civil uprising lies not only within its descriptive textual context that calls for a free and just nation, but also in its viewers’ desire to make sense of cultural trauma as it unfolds in the present time. Recycling such Dazibao aesthetics, the dissensus community evokes an unexpected and unnerving dimension to the current Chinese political landscape, one that, upon viewing, is reminiscent of the chaos and violence of the Cultural Revolution. The intensely emotional nature of the memory of the Cultural Revolution is further compounded by the use of blood-like paint on the signs, so as to make the viewing experience feel like a jarring and disconcerting disruption.

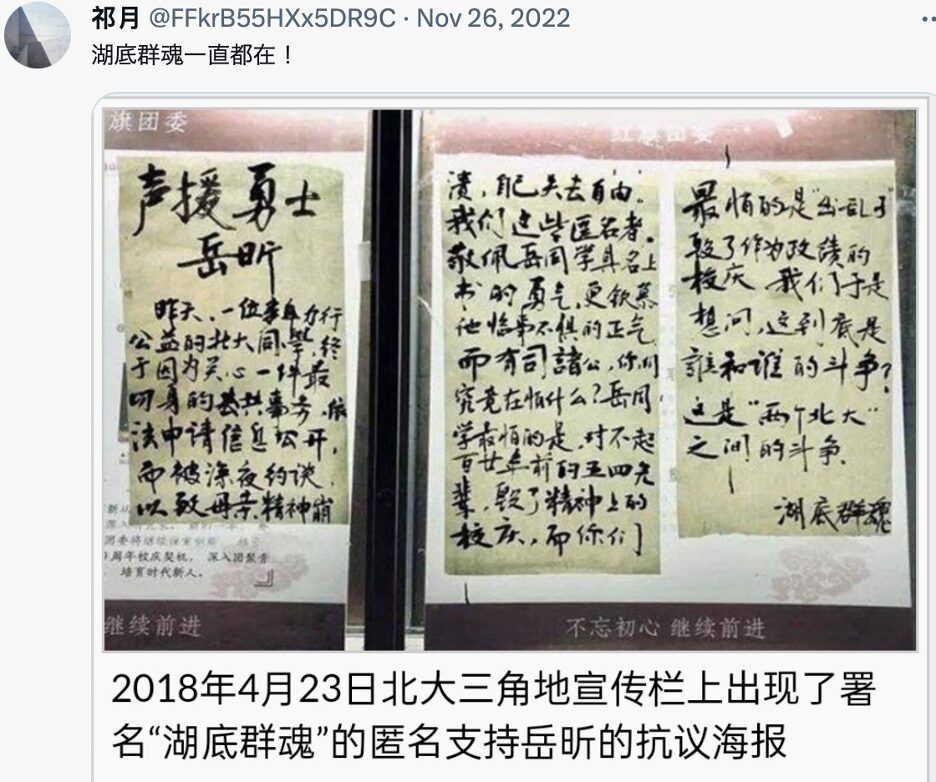

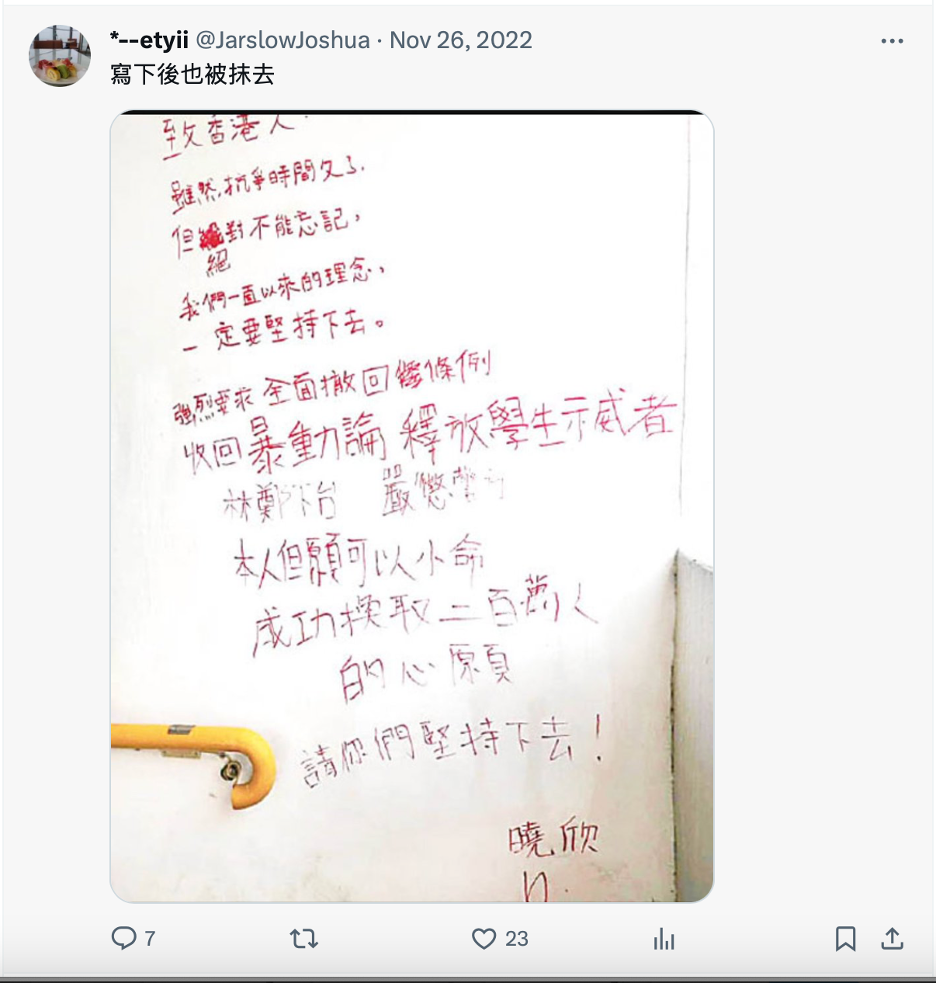

Internet users also showed a keen recognition and response to the Dazibao aesthetic by actively engaging in discussions and sharing similar visuals on online forums (see Figures 9–10). These pictures are often posted with very few words to accompany them. The act of citing visuals that align with the Dazibao style serves as a unifying language, fostering a sense of shared purpose and solidarity among online communities. This digital iteration of the aesthetic not only transcends physical boundaries but also enhances the collective identity and communication among participants in the broader sociopolitical dialogue. Since the key force of the A4 Revolution is the young, educated urban population, appropriating visual references from an era of national trauma can effectively induce the strong viscerality of shock, dread, and anxiety among older generations and the working class, and forge communities across generational and class boundaries. This process is an illustrative instance of critical inheritance from the bottom up. Although Dazibao was primarily used by the CCP in the twentieth century as a means to manage public dissent and solidify the authoritarian state’s rule, in its twenty-first-century citation, it instead serves as a medium for re-understanding the past, and reinterpreting in response to the present circumstances. Memory invoked by the Dazibao aesthetic is transformed into a counter-hegemonic cultural discourse in the present.

Figures 9–10. Online posts of Dazibao aesthetic.

Modern Literature from Anti-Imperial Times

The second type of affective visual signs is a repurposing of the anti-colonial literature and posters from the early twentieth century. Specifically, anti-imperial writing on personal freedom and liberty is frequently quoted. One of the most commonly seen signs during the protest originated in Liang Qichao’s provocative pamphlet “On Liberty” (1902) (see Figures 11–12). Liang Qichao (1873–1929) famously reused American politician Patrick Henry’s words, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” (不自由毋宁死!]). Throughout the piece, Liang expresses a strong emotional commitment to the importance of individual autonomy, the right to free expression, and the freedom to pursue knowledge and truth, and that this freedom is essential to the development of a strong and prosperous society.

Figures 11–12. Signs with a quote from Liang Qichao: “Give me liberty, or give me death!”

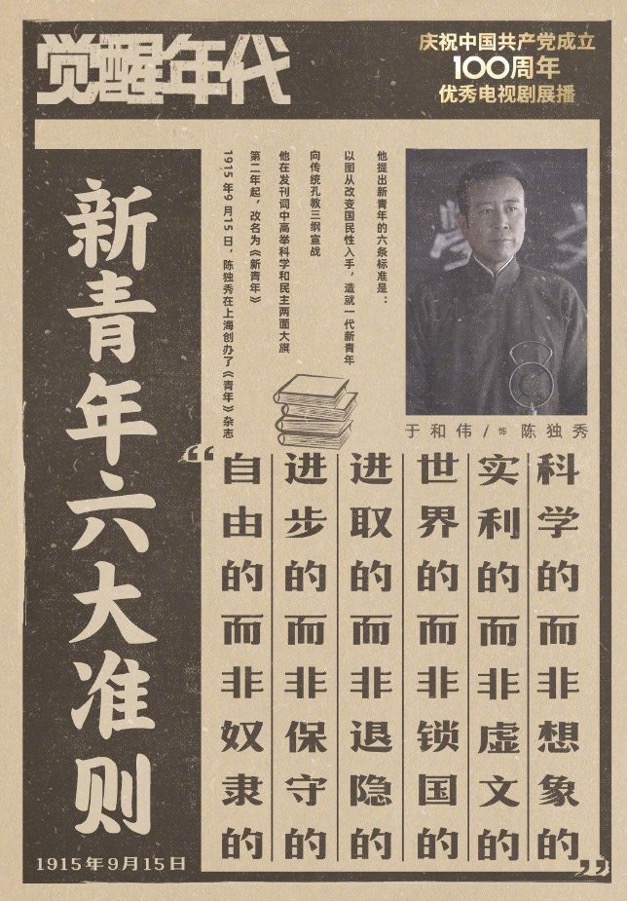

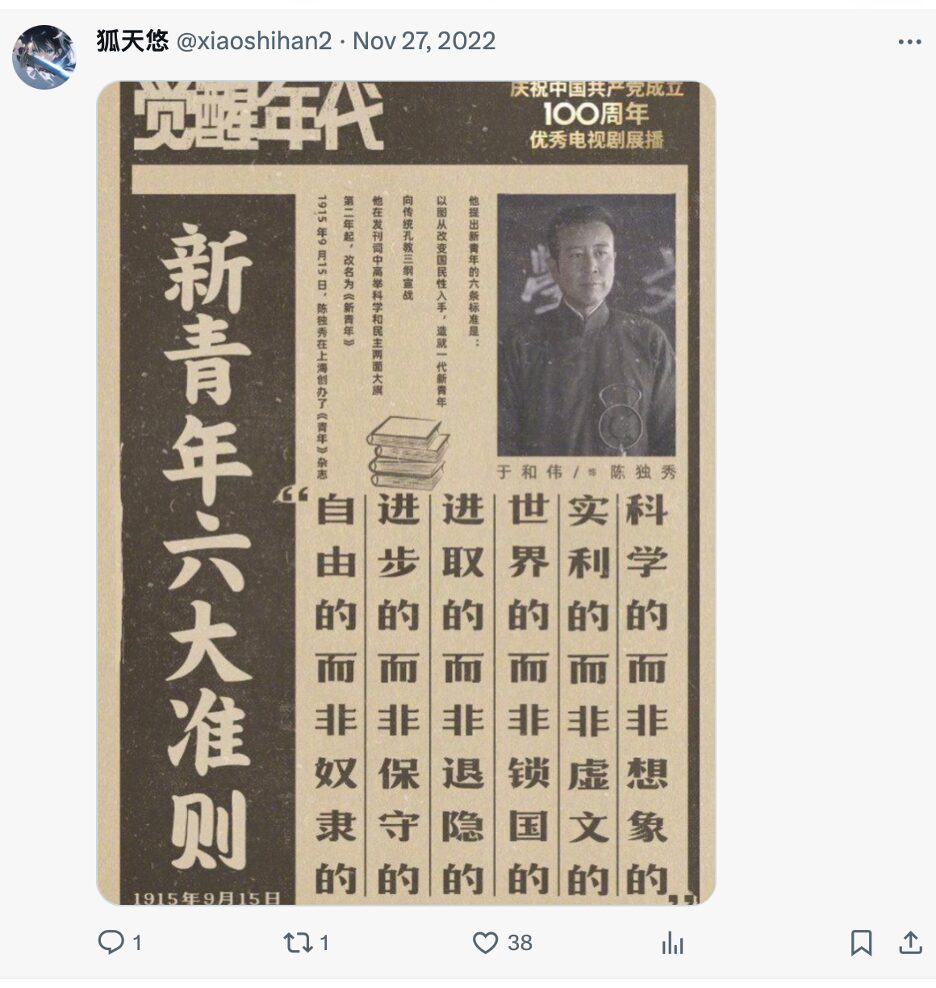

The cover page of the New Youth magazine is also one of the popular visual signs during the protest (see Figure 13). New Youth was a Chinese literary magazine founded by Chen Duxiu and published between 1915 and 1926. It strongly influenced both the New Culture Movement and the later May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1919) was characterized by a rejection of traditional Chinese values and a call for modernization, democracy, and social justice. The New Youth magazine was at the forefront of this movement, publishing articles and essays that criticized Confucian culture, advocated for the adoption of Western ideas and institutions, and called for social and political reform. One of the key emotions expressed by participants in the May Fourth Movement was frustration with traditional Chinese society and culture, particularly Confucianism. This frustration often manifested itself as anger, as participants in the movement criticized traditional Confucian culture and called for a radical transformation of Chinese society.

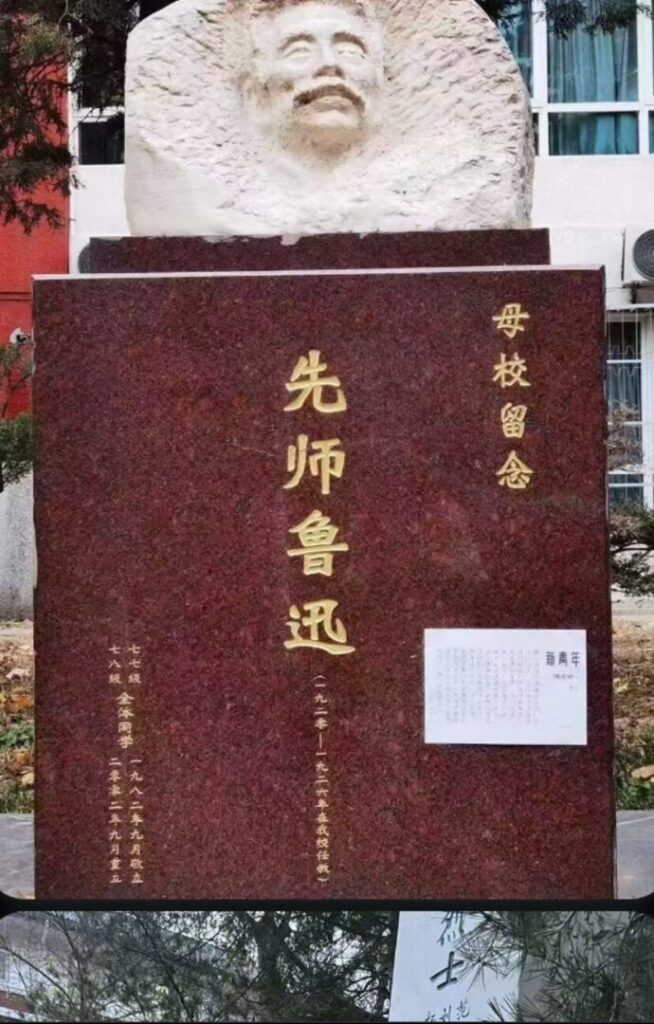

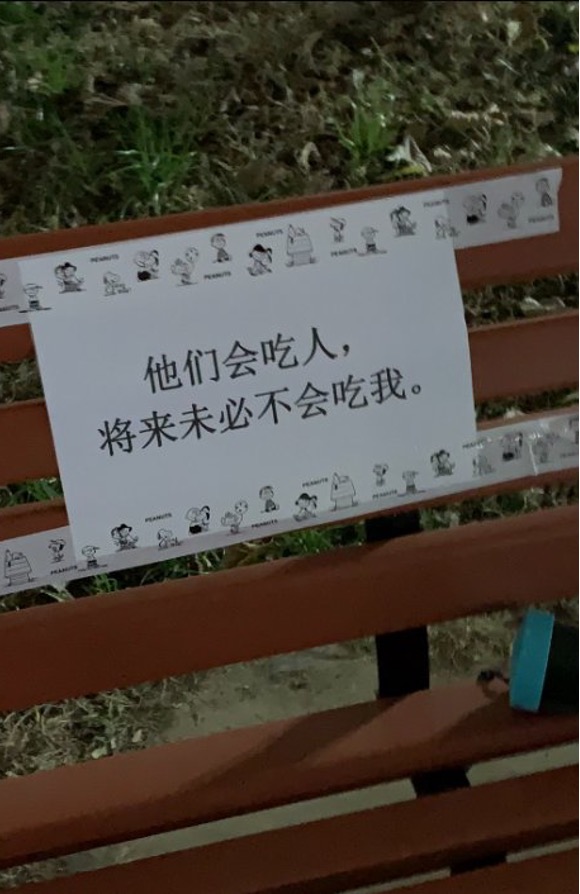

During the protest, quotes from Lu Xun’s 1918 “Diary of a Madman” ( 狂人日記) and 1922 “Call to Arms” (呐喊) are often seen on signs. “Diary of a Madman” was the first and most influential work written in vernacular Chinese in Republican-era China (see Figures 14–16). The short story is riddled with excessive fear and paranoia, as the protagonist is consumed by a growing conviction that the people around him are plotting to commit cannibalism against him. As a critique and social commentary, the protagonists’ fear, anger, and frustration are a metaphor for the madness of traditional Chinese culture and politics. Lu Xun (1881–1936) was one of the leading figures in left-wing political movements and a vocal critic of the ruling Nationalist government, and a symbol of Chinese resistance to oppression and exploitation. His writing is characterized by accessible language, heavy satire, and explicit outrage.

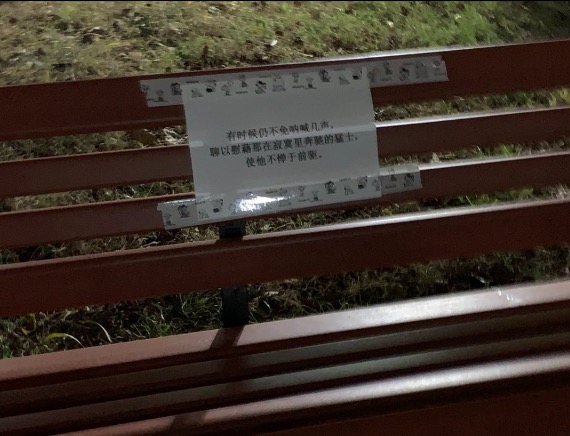

Figures 15–16. Two quotes from Lu Xun’s writings: (left) “Diary of a Madman” (1918): “They eat people. Can’t guarantee they won’t eat me in the future,” (right) “Call to Arms” (1922): “Sometimes I can’t help shouting a few times, talking to comfort the warrior who is running in loneliness, so that he will not be afraid of going forward.”

The anti-imperialists in the early twentieth century sought to replace the old-fashioned, pre-industrial glories of the Chinese empire with the industrial bourgeoisie’s New China. Early modern Chinese literature was in turn motivated by the implicit and explicit goal to overhaul Confucianism and modernize Chinese people, thoughts, society, and ways of life by introducing Western ideas of democracy and science.21 I do not intend to rehearse the abundant scholarship on early modern Chinese literature and its explicit and implicit connection with themes such as liberty, self-determination, science, and democracy. My interest, rather, is the ways in which the writing of the imperial past is constructed with heightened senses of anger, shame, and indignation. After all, Lu Xun, the founding father of modern Chinese literature believed that only literature has the capacity to “spiritually stir people and move them to action.”22

Emotional excess and the need to elicit mass affective reactions characterize anti-imperial writings. According to Haiyan Lee (2007), modern Chinese literature initially depicted grassroots society as emotionally detached (222). Lu Xun’s work, for instance, primarily aims to cultivate a sentiment-driven sense of unity among Chinese individuals, transcending familial and local affiliations. His work sought to foster a universal, emotion-based identity, encouraging compatriots to empathize with anti-imperial efforts and connect on a broader scale.

The symbols and iconography of early twentieth-century anti-imperial movements used in the twenty-first-century protests are not just intended to assert a particular form of cultural identity, but also to give a tangibility to deeply held, antagonistic political views involved in the early twentieth century—a form of critical inheritance initiated by the populace. Beyond their symbolic and aesthetic meanings, the signs convey a particular memory of past behavior and feeling—the urgent need to wake up the masses from their emotional detachment and conjure up the power of popular dissent against authority. Early twentieth-century literature finds its parallel democratic purpose today. Over a hundred years later, in 2022, the literary references represent the memory of unexperienced events. As Morphy and Morphy remind us, collective memory is dynamic and shaped by cultural practices.23 Rather than being a static repository, memories are actively worked on and adapted to suit present needs. The 2022 protesters use images of the past to draw parallel connections with the present, and the collective memory of the early twentieth century serves as a generator of meaning. The contemporary appropriation of these signs co-opts and re-engages the cultural memory of colonial indignation. The iconographies of Lu Xun, Liang Qichao, and New Youth magazine are extremely well-known within the Chinese standard education system as essential parts of national history, collective memory, and cultural references. The quotes from “On Liberty” and “Diary of a Madman” have been a fundamental part of Chinese literary education, therefore not requiring extensive knowledge or nuanced reading to grasp their intended meaning. These images and quotes hold significant meaning and can evoke shared experiences, emotions, or ideas across generations. They work as immediate and almost automatic affective memory triggers, exerting impact based on the feeling it provokes, not the reading it enables. Upon viewing these references, viewers identify with the emotions situated within the cultural memory of anti-imperial struggles and are invited to make connections with the status quo. This is the critical inheritance protesters were engaged in—to inherit the affective dimension of these works, and most importantly, to critically draw parallels between the imperial past and authoritarian present as they both are ultimately concerned with similar problems: the harm done by undeserved privileges, economic and symbolic oppression, and freedom taken away by force.

Under the social media posts of these images of anti-imperial signs at the protest, Chinese netizens recognize the strategic nature of citing history (see Figures 17–18). They often reiterate the slogan “Give me liberty or give me death” in the comment sections. Internet users’ comments include “Just like this, we need to learn to protest smart” and “This sentence has been around for so long, now it finally is said out loud across the nation.”24 Recycling these literary works and iconographies beyond the anti-imperial context becomes a moment of critical inheritance from the bottom up. Netizens demonstrate the ability to engage with and challenge established literary canons, extracting revolutionary energy and repurposing it for their own contemporary objectives. This act of repurposing serves as a form of cultural resilience, allowing individuals to reinterpret and adapt historical symbols and narratives to address current issues and express dissent or resistance. As Marx reminds us, revolutions “conjure up the spirits of the past to their service”—both of the two strategies elucidate the relationship between civil disobedience and national imaginings.25 Both Dazibao and anti-imperial literature aesthetic strategies in this protest draw on the affective dimensions by aiming to eliminate historical distance and draw connections between past and present. They achieve this by evoking a mood and atmosphere closely tied to the traumatic events and injustices of the twentieth century, while utilizing materials endorsed by the state.

Figures 17–18. Two social media posts of an anti-imperial student movement at Peking University (left) and the cover of New Youth online with no additional caption (right).

A Piece of White Paper

Lastly, another affective visual sign of the A4 Revolution is the namesake, a blank sheet of A4 paper. Demonstrators around the world hold a piece of paper over their faces, sometimes wearing masks, to protest the party-state’s violation of the freedom of speech (see Figure 19). Others posted white squares on their social media platforms (see Figure 20). As of May 2024, it remains unclear who was the first student at Nanjing Communication University to start holding white paper. According to the major information source on Twitter, dubbed Teacher Li (@whyyoutouzhele), the true identity of the initiator of the strategy is unknown.26 Li Kangmeng, a protester who was arrested in Shanghai, has allegedly been the initiator; however, this information is not confirmed by any credible sources. The political force of the aesthetic itself is embodied in this blurring of speakers and their identities. The A4 Revolution, characterized by its ambiguous start and mask-wearing participants, is a truly faceless movement. The collective holding of white paper creates a “sensory reality that would abolish the very distance . . . between one speaker and another speaker.” 27 This fosters a sense of collectivity among participants, as everyone is seen as part of a unified community rather than as individuals with varying backgrounds or statuses. It allows people from diverse backgrounds to come together and express solidarity, reinforcing a shared identity based on the issue at hand. Further, in an environment where political dissent is met with persecution or legal consequences, anonymity shields individuals from being easily targeted or identified, creating a sense of support, comfort, and empowerment among participants.

Perhaps the piece of white paper also cites the common internet slang “I’m being 404’d.” Error 404, an issue indicating the requested URL cannot be found on the server, accompanied by a glaringly white empty webpage, has become a codeword for Chinese censorship of the internet (see Figure 21). When scandals or misdeeds become exposed online, “404” becomes a tool for the state to manage public opinion and public relations by simply taking the information down from the internet. To “404” someone is a powerful course of action exclusively controlled by the state: the watchful eye and omnipotence to suppress all competing sources of information work to cement CCP’s rule. However, protesters in the A4 Revolution critically inherit “404” from the bottom up, reclaiming the right to “404.” Beyond affording a certain level of anonymity and protection, the protester’s holding of “404” symbols becomes an aesthetic because of the critical reflection involved in this visual. It plays the role of “a transformation of a certain state of relations between words and things, between words and the visible, a certain organization of the senses and the sensory configuration of what is given to us and how we can make sense of it.”28 A blank page, with no textual information beyond telling the viewer that the content they seek no longer exists, intentionally makes a mockery of the state’s elusive yet paranoid governing of speech. The simple visual of a piece of white paper over one’s face forms a community of dissensus comprised of those who have experienced being deprived of political discussions by means that go beyond linguistic availability. Although without any words, this aesthetic sarcastically asks the question: why are you afraid of a blank sheet of paper? And it gives the answer: whatever you are afraid of is what is written on the paper (see Figures 22–23).

In this way, the piece of white paper is profoundly strategic and satirical, “a new way of dealing with words—with words and meanings,” because no word needs to be said.29 This aesthetic is, on the surface, completely muted and silent, but is able to convey democratic messages loud and clear. Moreover, this mode of expression is remarkably accessible, transcending geographical and temporal boundaries. Participation is not confined to physical spaces or specific moments; it extends to anyone, anywhere, and at any time. Beyond the demonstrators physically holding plain papers on the streets, many online communities embraced a virtual iteration by sharing blank white squares in digital spaces (see Figure 20). The simplicity of this blank visual requires minimal language, yet it encapsulates profound emotions. Filled with frustration, anger, and contempt, the piece of white paper is configured by the mutual understanding between the public and the authoritarian regime about the unsayable message. The affects, feelings, and embodied responses are experiences that are forced out of precise verbal articulation within contemporary Chinese citizens’ everyday discourse. They exist in a realm that does not allow a linguistic expression, thus remaining somewhat ambiguous or challenging to capture fully in words. The task of dealing with this deeply felt indignation of being “404’d” is typically relegated to the privacy of the individual. A single post being taken down, a comment being deleted, a beloved website being no longer available, these common 404 encounters are usually limited to the individual and their mobile device. However, by publicly visualizing this collective vulnerability in everyday spaces—whether online or in person—the white papers carry a profound affective power. They became a language and resource for political solidarity and community formation, highlighting shared experiences and fostering a sense of community in these alienating “404” moments. The state’s “404” measures were intended to disband communities, yet the A4 Revolution’s aesthetic critically inherited these visuals, repurposing them to construct anti-authoritarian communities. This innovative use of the “404” symbol transforms a tool of suppression into a rallying point for collective resistance, demonstrating the power of creative reinterpretation of symbols to foster solidarity and unity among those challenging authoritarian regimes. As Rancière reminds us, politics is largely a struggle over visibility: over what and who can be seen, and in what ways. The moment the state started to censor blank paper, the paranoia and irrationality of its rule were exposed and a redistribution of the sensible took place. Demonstrating with the paper thus represents a strategic disruption of the hegemonic representational logic that is self-reflexive, pragmatic, and political. It renders visible the schema of visibility and sayability under the police order of the authoritarian regime, affectively reconfigures the social order by appropriating, mocking, and revealing the hegemonic violation against citizens’ rights and the material and social violence that they conceal.

Conclusion

A month after the Anti-Zero-COVID Protests, China ended its anti-COVID measures and reopened its door to the world. The debate over the contribution of the A4 revolution to this dramatic policy change is still ongoing. Some believe the protesters were successful in forcing the state to comply with its people,30 while others think the economic downturn determined that the reopening was inevitable regardless.31 After all, the authoritarian party-state holds absolute control of violence. Protesters are arrested and interrogated, and some may never be seen again, while Xi and his CCP remain untouchable by the civil uprising. However, the 2022 protests were still a historic occurrence under Xi’s iron fist rule because of their scale and depth. In their extensive review of the post-Tiananmen protests and their scholarship, Yen-Hsin Chen and T. David Mason (2023) demonstrate that there are three unique features: first, they are not national, small in scope, motivated by disputes over local issues; second, their demands are tangible and material, rather than political; third, they are usually spearheaded by peasants and workers, instead of student-led. However, the A4 Revolution is a nationwide and international movement that impacted at least twenty-one provinces in the country and overseas.32

Major cities, starting with Nanjing and Shanghai, followed by Beijing, Guangzhou, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Shenyang, Harbin, Changchun, Chongqing, Chengdu, Lanzhou, Hangzhou, Xi’an, Wuhan, Zhengzhou, Dali, Changsha, Jinan, Taiyuan, Urumqi, Lhasa, Foshan, and Zhuhai, all witnessed waves of street protests organized by students. Their goal was not only material—to speak against their mass confinement in the name of COVID and regain their physical freedom—but it was also distinctively political: to sympathize with their fellow minority Chinese citizens and to question Xi’s and the Party’s authoritarian rule. The A4 Revolution is explicit in its discontent with the party’s and Xi Jinping’s rule (see Figures 24 and 25). On the evening of November 26, 2022, Shanghai citizens protested on Urumqi Middle Road, calling for the CCP and Xi Jinping to step down.33 Particularly among Chinese diasporic communities, the signs demanding the end of authoritarian dictatorship were circulated on social media, inviting a “public gaze, serving as a mode of aesthetic communication not only with a national but also with a global audience.”34 Perhaps inviting a global audience to witness the protest is a strategy to archive the movement, a way to not be completely wiped off and wither away, though the effectiveness of it remains uncertain. Since the hashtag #WhitePaper (baizhi) was quickly censored on Weibo, the A4 Revolution heavily relied on Twitter to circulate images of dissent and evidence of police brutality. As some protesters were arrested and interrogated, the survivors of the protest started a Twitter account (@whitepaper_op) in the hope of reuniting with previously lost participants, continuing to pass on the spirit of the movement, and realizing democratic aspirations in mainland China.35 The account now circulates images and information not exclusively regarding anti-COVID measures, but anti-CCP discourse at large, including memorializing the 1989 protest victims, Hong Kong independence, and exposing ethnically motivated persecution, etc. Although the protests waned after the reopening of the country, the piece of white paper has morphed into a symbol of dissent against Xi Jinping and his rule.

In this sense, the A4 Revolution defies all three categorical features of post-Tiananmen protests, making it a historically distinctive and therefore significant case to study at the current historical conjuncture in China. The movement is unique in its strategic mobilization of visual cues with Chinese historical and cultural specificities. These simple yet striking visual signs critically recontextualize and reinterpret history and political reality, tapping into the affective energy of well-known stories and inspiring fresh political visions and possibilities. New perspectives, democratic voices, and previously suppressed narratives are afforded a newfound language and are able to come to the forefront. They enabled the community to emerge as an identifiable political subject through the traumatic history of colonialism and misguided socialism. These affective aesthetics are important disruptive forces of critical inheritance from the bottom up: they disfigured the distribution of perception by making visible the similarity between the current historical conjuncture and times of national trauma. These protests offer a valuable epistemology to delimit “spaces and times, of the visible and the invisible, of speech and noise, that simultaneously determines the place and stakes of politics as a form of experience.”36 Via affective and aesthetic dissensus, the wave of protest in China created a new form of communication and community across class lines, a new way of being in the face of authoritarianism, and thereby a new “distribution of the sensible.” Both artful and strategic, the protests critically inherit materials that were deemed permissible by the Chinese state, be it blank paper, canonical literature, or imaginaries common in history books, and reconfigure them into taboos that need to be censored. The A4 Revolution serves as a compelling reminder that aesthetics is a distinct medium of cultural memory and a mobilizing strategy to (re)present visions of the past and the political present. It is a crucial, self-reflexive, and strategic language crafted by the populace to articulate democratic demands within authoritarian settings, affording the transformative power of visual symbols and creative expression in shaping collective resistance.

Notes

- Jacques Ranciere and Slavoj Zizek, The Politics Of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004. ↩

- Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics And Philosophy, First Edition, trans. Julie Rose. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 30. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, trans. Robert Hurley (San Francisco: City Lights Publishers, 2001). ↩

- Jonathan Flatley, Affective Mapping: Melancholia and the Politics of Modernism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674036963. ↩

- Stephen Duncombe, “Affect and Effect: Artful Protest and Political Impact,” in The Democratic Public Sphere: Current Challenges and Prospects, ed. Henrik Kaare Nielsen, Christina Fiig, and Jorn Loftager (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2016), 438. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2002), 475. ↩

- Michael E. Hobart, “The Paradox of Historical Constructionism,” History and Theory: Studies in the Philosophy of History 28, no. 1 (1989): 43–58, https://doi.org/10.2307/2505269. ↩

- Kuo-shu Yang, “Chinese Personality and Its Change,” in The Psychology of the Chinese People, ed. Michael H. Bond, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 106–70. ↩

- Tong Zhang and Barry Schwartz, “Confucius and the Cultural Revolution: A Study in Collective Memory,” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 11, no. 2 (1997): 189–212, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025187406580. ↩

- James Griffiths, The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet (London: Zed Books, 2019); Margaret E. Roberts, Censored: Distraction and Diversion inside China’s Great Firewall (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018); Florian Schneider, China’s Digital Nationalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩

- Xi Chen, Social Protest and Contentious Authoritarianism in China (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139053310. ↩

- Ze Hua and Youyu Xu, In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon: Stories of Repression in the New China (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). ↩

- Sara Liao and Luwei Rose Luqiu, “MeToo in China: The Dynamic of Digital Activism against Sexual Assault and Harassment in Higher Education,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 47, no. 3 (2022): 741–64, https://doi.org/10.1086/717712; Cheryl Teh, “China Blocked Candle and Cake Emojis from Weibo in Order to Censor Anniversary Commemorations of the Tiananmen Square Massacre,” Insider (blog), June 4, 2021, https://www.insider.com/chinese-censors-blocked-candle-emojis-anniversary-tiananmen-massacre-2021-6; Jing Zeng, “You Say #MeToo, I Say #MiTu: China’s Online Campaigns against Sexual Abuse,” in #MeToo and the Politics of Social Change, ed. Bianca Fileborn and Rachel Loney-Howes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15213-0_5; Yuqiong Zhou and Yunkang Yang, “Mapping Contentious Discourse in China: Activists’ Discursive Strategies and Their Coordination with Media,” Asian Journal of Communication 28, no. 4 (2018): 416–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2018.1434803. ↩

- Xijin Hu, “胡锡进:乌鲁木齐已调整疫情防控政策,形势向好” {Hu Xijin: Urumqi Has Adjusted the Epidemic Prevention and Control Policy, and the Situation Is Improving}, Sina News (blog), August 25, 2020, https://news.sina.com.cn/c/2020-08-25/doc-iivhvpwy2876869.shtml. ↩

- Hu, “乌鲁木齐” {Urumqi}. ↩

- Austin Ramzy and Fan Wenxin, “乌鲁木齐火灾如何点燃中国各地的抗议之火” {How the Urumqi fire ignited protests across China}, 华尔街日报中文网 (blog), December 2, 2022, https://cn.wsj.com/articles/乌鲁木齐火灾如何点燃中国各地的抗议之火-11669874105; Sun Shengran, “新疆10死火警救援惹議 傳防疫圍欄阻消防車入小區水柱噴不到單位” {Fire causes 10 dead in Xinjiang provokes controversy. Rumor says Covid prevention fence prevents fire trucks from entering the community, and the water jet cannot spray the unit}, HK01 (blog), November 25, 2022, https://www.hk01.com/即時中國/840473/新疆10死火警救援惹議-傳防疫圍欄阻消防車入小區水柱噴不到單位; “网传新疆火灾消防救援被防疫措施延误” {It is reported on the Internet that fire rescue in Xinjiang was delayed by epidemic prevention measures}. Zaobao (blog), November 25, 2022. https://www.zaobao.com.sg/realtime/china/story20221125-1337064. ↩

- “中国防疫人员入民宅‘无害化处置’宠物狗,引发众怒” {Chinese anti-pandemic personnel enter private houses to ‘harmlessly dispose’ pet dogs, sparking outrage}, BBC News 中文 (blog), November 16, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/chinese-news-59289251; Initium Media,上海封城:市民被多名防疫人員追打,民眾不滿物資短缺,與防疫人員互相指罵 {Lockdown of Shanghai: Citizens Were Chased and Beaten by Anti-Pandemic Personnels. The Public Was Dissatisfied with the Shortage of Supplies and Blamed the Anti-Pandemic Personnel}, 2022, YouTube video, 2:45, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OW2BGLH1R0s.; Li Na, “富士康内部员工自述:混乱现象是怎么造成的?” {Foxconn Employee’s Self-Narration: How Did the Chaos Occur?}, Yicai (blog), October 31, 2022, https://m.yicai.com/news/101579289.html; Xia Xiaohua, “坚持清零 中国多地现文革式暴力防疫” {Insistent on Zero Covid: Cultural Revolution-style violent pandemic prevention in many places in China}, Radio Free Asia (blog), April 6, 2022, https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/huanjing/hx-04062022074626.html; Huimi Yang and Xinlu Chen, “西安警方通报2名防疫人员殴打他人:打人者道歉,被拘7日” {Xi’an Police: 2 Anti-Pandemic Personnel Beat Ciivlians: The Assailant Apologized and Was Detained for 7 Days}, The Paper (blog), January 1, 2022, https://m.thepaper.cn/rss_newsDetail_16115630. ↩

- Hua Sheng, “Big Character Posters in China: A Historical Survey,” Journal of Chinese Law 4 (1990): 234–56, https://doi.org/10.7916/cjal.v4i2.3106. ↩

- Hubei Caifeng Weiyuanhui, 大字报选集 {Selection of Dazibaos} (Hubei: 湖北人民出版社, 1959); Bing Zhou, “大字报文艺论略:以1958年前后为例的考察” {A Brief Discussion on the Literature and Art of Dazibao: Taking 1958 and Around 1958 as an Example}, Tian ya 4 (2013): 197–202. ↩

- Elizabeth J. Perry, “Moving The Masses: Emotion Work In The Chinese Revolution,” Mobilization 7, no. 2 (2002): 111–28, https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.7.2.70rg70l202524uw6. ↩

- Ming Dong Gu, Routledge Handbook of Modern Chinese Literature (Boca Raton, FL: Routledge, 2018). ↩

- Xun Lu, Lu Xun San Shi Nian Ji, di 1 ban (Xianggang: Xin yi chu ban she, 1968). ↩

- Howard Morphy and Frances Morphy, “The ‘Myths’ of Ngalakan History: Ideology and Images of the Past in Northern Australia,” Man 19, no. 3 (1984): 459–78, https://doi.org/10.2307/2802183. ↩

- @TOGETHER_CHG_CN, “這個口號。。。好久了,終於再次響徹整個大地,” X, November 27, 2022, https://x.com/Together_CHG_CN/status/1596836928615510017. ↩

- Karl Marx, “Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” trans. Saul K. Padover (1852, 1869), Marxist.org, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm. ↩

- @whyyoutouzhele, “目前可以确定的是,网传的李康梦和照片并不是南广的这名同学。 李康梦是一名在上海被捕的女子,关于她为何被捕,我亦正在求证更多准确的信息” {What can be confirmed at present is that the Li Kangmeng and the photo posted on the Internet are not the classmate of Nanguang. Li Kangmeng is a woman arrested in Shanghai. I am seeking more accurate information about why she was arrested.}, X, December 2, 2022. https://twitter.com/whyyoutouzhele/status/1598769745796505600. ↩

- Anne Marie Oliver, “Aesthetics against Incarnation: An Interview by Anne Marie Oliver,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (2008): 172–90, https://doi.org/10.1086/595633, 176. ↩

- Oliver, “Aesthetics,” 174. ↩

- Oliver, “Aesthetics,” 174. ↩

- Huang Yang, “黄杨:闲聊‘白纸运动’” {Huang Yang: Chatting about the ‘White Paper Movement’}, CND (blog), December 12, 2022. http://hx.cnd.org/2022/12/12/%e9%bb%84%e6%9d%a8%ef%bc%9a%e9%97%b2%e8%81%8a%e7%99%bd%e7%ba%b8%e8%bf%90%e5%8a%a8; Jody Rosen, “如何在审查中抗议?一张掷地有声的白纸” {How to protest during censorship? A piece of white paper with great sound}, New York Times China, December 23, 2022, https://cn.nytimes.com/china/20221223/white-paper-protests-censorship. ↩

- Keith Bradsher, Che Chang, and Chien Amy Chang, “中国抗疫政策‘大转弯’,大范围放松防控规定” {China’s anti-epidemic policy makes a ‘U-turn’, relaxing prevention and control regulations on a large scale}, New York Times China, December 8, 2022, https://cn.nytimes.com/china/20221208/china-zero-covid-protests. ↩

- Initium Media, “Update: The mourning event for Yintai in Lakeside Hangzhou was deployed ahead of time by the police, and the crowd was taken away and the venue was cleared,” Initium Media (blog), November 29, 2022, https://theinitium.com/article/20221127-mainland-students-protest; Yuting Liu, “白紙革命燒到布拉格!難得一見的中港台留學生齊聚示威,聽聽他們怎麼說” {The Blank Paper Revolution Burns to Prague! It’s Rare to See International Students from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan Gather to Demonstrate, Listen to What They Have to Say}, Crossing (blog), November 30, 2022, https://crossing.cw.com.tw/article/17030. ↩

- China Digital Space, “白纸革命 – China Digital Space,” accessed June 6, 2023, https://chinadigitaltimes.net/space/%E7%99%BD%E7%BA%B8%E9%9D%A9%E5%91%BD. ↩

- Charis Boutieri, “The Democratic Grotesque: Distortion, Liminality, and Dissensus in Post-Revolutionary Tunisia,” Cambridge Anthropology 39, no. 2 (2021): 59–77, https://doi.org/10.3167/cja.2021.390205. ↩

- WhitePaperRevolution {@whitepaper_op}, “我们是最初白纸革命抗议行动中的幸存者,我们的伙伴有许多被捕之后都下落不明,所以我们才成立了这个组织。 一是想与之前失散的伙伴重聚,二是继续将‘白纸革命’的精神传承下去,并期望能在中国大陆实现我们的诉求。” {We were survivors of the original White Paper Revolution protests. Many of our partners were arrested and their whereabouts were unknown, so we founded this organization. One is to reunite with our previously separated partners, and the other is to continue to pass on the spirit of the ‘white paper revolution’ and hope to realize our demands in mainland China.}, X, January 13, 2023, https://twitter.com/whitepaper_op/status/1613689826053881856. ↩

- Rancière and Zizek, Politics Of Aesthetic, 13. ↩