The sweet, musky smell of burning weed confirmed I was in the right place, an underground cannabis Christmas party in Los Angeles, at a recording studio near Boyle Heights called “The Void” (December 23, 2023). Parked in front was a Black owned taco truck called “All Flavor, No Grease” I’d seen before at similar events. After passing through security (bag check, pat down), I walked through the chain link fence and into the parking lot, a long line of people snaking out the venue (Figure 1). Except for a handful of white people, including my partner who tagged along, everyone was Black or Latinx. They were also young, with many in their twenties. But as a 60-year-old Chicano, I stand out, even with my scene-appropriate kicks and cannabis-branded hat. One young Black and Latinx couple stopped us to ask about our relationship and history with cannabis. Another patron asked to take my picture, good naturedly bemused to see someone there his grandfather’s age. At other events young cannabis enthusiasts have given me cannabis and cannabis swag seemingly for similar reasons. Black and Latinx recreational cannabis cultures in California are relatively intergenerational, including young and old consumers, and older cannabis growers and sellers, such as Cheech and Chong, who are in their seventies and eighties respectively.1

Inside, the Void’s two large rooms were lined with vendor tables displaying cannabis infused chocolates, boba drinks, beef jerky, and lots of weed (Figure 2). Smoke and street fashion were thick and dank (check out the light halos in the event photos). Several people wore cannabis-themed ugly Christmas sweaters, and one young woman was dressed as an elf while she smoked cannabis concentrates from a glass rig (Figure 3). The main room featured a large boxing ring, which alternated between boxing matches and rap performances, including by Theo Lewis, owner of Teds Budz, the cannabis distribution company I discuss later in this essay .

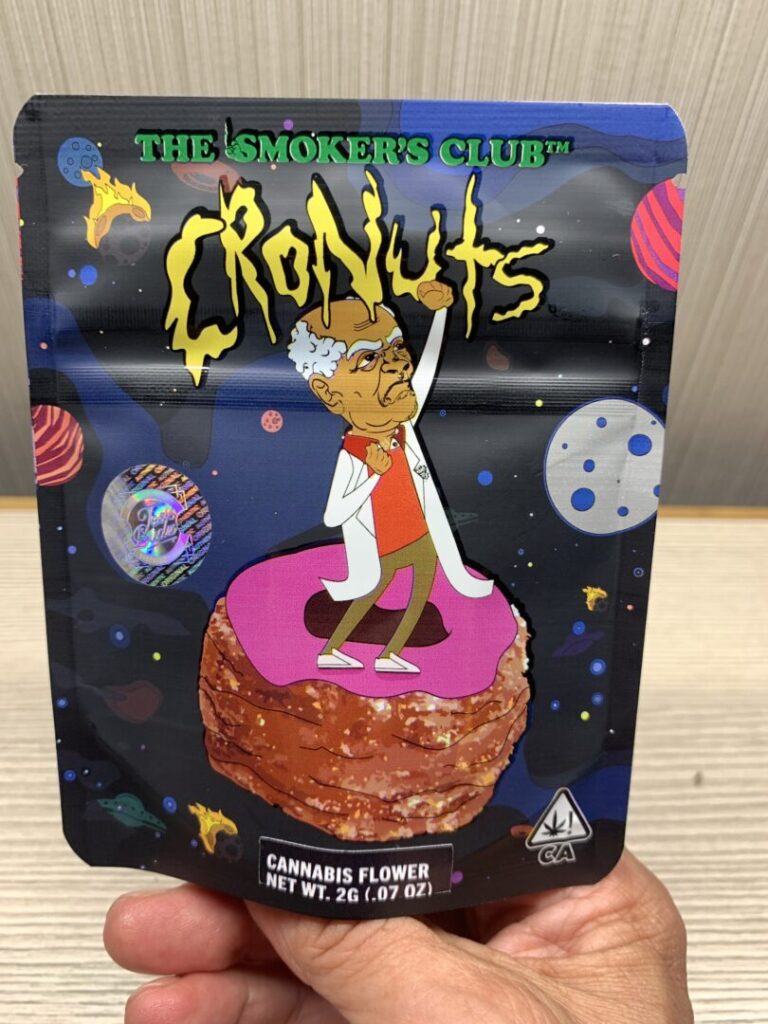

Cannabis observers in California distinguish between an illegal “black market” and a legal “white market,” but this event was grey. I would be surprised to learn that the event’s promoters had acquired the appropriate permits for boxing matches, and there didn’t appear to be any medical workers there in case of injury. Moreover, none of the vendors charged sales taxes or cannabis excise taxes as required by state law and hence may not have had a retail permit. Resistance to cannabis sales taxes by working-class Black and Latinx consumers is partly a response to their regressive nature: taxes imposed on cannabis brands marketed to working-class people of color represent a disproportiante burden for those consumers relative to wealthier, white cannabis consumers. Finally, venders used a mix of legal and illegal packaging. Some displayed pounds of cannabis in large plastic bags the size of office trash can liners, while others sold small, mylar bags filled with 3.5 grams of cannabis as required by law. In contrast with the plain plastic bags, the mylar bags became canvases for art advertising their contents. One vendor even had bags designed to look like abstract paintings in ornate gold frames (Figure 4).

Encouraged by state requirements for prepackaging, Black and Latinx producers and distributors of legal cannabis in California have developed novel, symbolically and socially significant forms of marketing. In the neighboring state of Oregon, a consumer at a dispensary encounters gallon-size jars of cannabis from which a budtender weighs out the desired amount and packs it in a nondescript, childproof plastic pill bottle with a simple label. That was the system in California during the era of medical marijuana, but with the legalization of recreational use the state requires cannabis to be prepacked, generally in 3.5-gram amounts. While not the aim of state regulations, the California requirement has led to the creation of increasingly elaborate packages and labels.

Black and Latinx cannabis industries have developed their own “commodity aesthetics,” using product packaging, for example, to entice buyers with a combination of attractive sights, smells, textures, and symbols that represent the contradictions of working-class Black and Latinx life in contemporary California. Commodity aesthetics is a term used by Marxist cultural critics to understand how advertising appeals to the senses. Often studied as paradigmatic commodities, stimulating and intoxicating products such as tea, coffee, alcohol, and tobacco have long and well-developed advertising histories. Although plantation intoxicants have historically been produced by slaves and low wage Black, Latinx, and Asian farm workers, the emerging legal cannabis industry in California is partly driven by Black and Latinx growers, entrepreneurs, and consumers. California’s commercial cannabis landscape includes boutique dispensaries and Las Vegas–style super stores; branded clothing and accessories; billboards and extensive and varied social media promotion; cannabis hotels, vacation rentals, consumption lounges, and spas; cannabis competitions, trade shows, music festivals, strain-launch parties, and dispensary pop-ups; and of course, cannabis packaging. Cannabis commodity aesthetics appeal to working-class consumers of color with discourses promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion. Consuming cannabis is often celebrated as honoring Black and Latinx communities, like Black History Month and Hispanic Heritage Month, two commemorations that businesses take advantage of to promote cannabis. Cannabis advertising not only affirms cultural identities and diversity but also eroticizes them, selling cannabis with images of young Black and Latinx bodies. Finally, marketing links cannabis consumption to idealized images of the good life and upward mobility that partly present critical reflections on the material limits of Black and Latinx lives.

Black and Latinx cannabis cultures combine images of freedom and transcendence with depictions of the low wage jobs that many Black and Latinx people work. This is because, rather than an impediment to work, cannabis consumption is a kind of support for or accessory to labor. Many consumers use it to dull the tedium and pain of labor and to sustain them throughout the workday. After a brief overview of the history of race, cannabis prohibition, and post-prohibition regulation, this essay provides a critical study of Black and Latinx cannabis marketing in California, and its targeting of working-class consumers of color. While I discuss several examples, my central case study is the successful Black and Latinx cannabis distributor Teds Budz. I draw on interviews, ethnographies of cannabis events, and visual studies of cannabis packages and social media, arguing that seemingly “escapist” qualities in cannabis culture critically foreground the material limits of the world from which Black and Latinx workers are trying to escape. Cannabis commodity aesthetics, I conclude, promise people of color an exit from the drudgery of work while more closely tying them to low wage labor.2 I conclude with a brief analysis of possible means of addressing such contributions by foregrounding cannabis unions.

From Prohibition to Regulation, or the History of Cannabis Racial Capitalism

California was the first western US state to criminalize cannabis in 1913.3 But federal criminalization of cannabis begins with the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937. From the 1930s though the 1950s and after, cannabis was caught up in complex racializations. Cannabis prohibition targeted Black people in the US south and, especially, Mexicans in the southwest, and as a supposed gateway drug, cannabis was ultimately articulated to China and to cold war anticommunism. In 1969, the Marijuana Tax Act was declared unconstitutional, and in response, the Nixon administration placed cannabis in Schedule I of the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, grouping it with heroin and cocaine as a drug without medical value but supposedly with significant potential for abuse. As it was previously linked to China, in the 1960s and 1970s cannabis was articulated, as a gateway, to heroin and framed by the anti-communist militarism of the Vietnam War. Nixon era criminalization, for instance, targeted rebellious Black people and anti-war hippies. In the late 1970s a number of states, including California, decriminalized cannabis possession, but the movement toward legalization was blocked by the Reagan administration, which again represented cannabis as a gateway drug, this time to cocaine. Hence the Reagan-era war on drugs used the racially coded threat of crack cocaine to police poor and working-class Black and Latinx people, who were disproportionately imprisoned for cannabis possession.4 As I argued in Drug Wars: The Political Economy of Narcotics, cannabis prohibition has been a means of controlling racialized labor by incarcerating or deporting surplus workers and disciplining those that remain. Drawing on my work and the work of others, Barney Warf thus argues that the regulation of cannabis represents a powerful form of biopower that states use to control racialized bodies and populations.5

In 1996, California decriminalized medical cannabis, but the law did not address or regulate cannabis production and sale, while the cost of acquiring a doctor’s recommendation excluded many poorer consumers. Given the historic stigmatization of cannabis and its continued criminalization at the federal level, others were afraid to go on record as cannabis consumers. Finally, in 2016, California voters passed Proposition 64: The Adult Use of Marijuana Act, which “legalizes specified personal use and cultivation of marijuana for adults 21 years of age or older; reduces criminal penalties for specified marijuana-related offenses for adults and juveniles; and authorizes resentencing or dismissal and sealing of prior, eligible marijuana-related convictions. The proposition includes provisions on regulation, licensing, and taxation of legalized use.”6

So-called legalization remains continuous with prohibition in many ways.7 Cannabis in California isn’t “legal” as in freely available but remains regulated and restricted. Indigenous nations are barred from participating in the cannabis market and threatened with federal raids and arrest.8 Meanwhile, criminal penalties for selling and consuming cannabis on the so-called black market, which accounts for most cannabis purchased in the state, remain in place. And while the total number of cannabis arrests in California have fallen post-prohibition, policing of the black market disproportionately targets Black and Latinx people. Given that cannabis culture skews young, it’s significant that Black and Latinx youth under 21, who are barred from the legal market, are disproportionately arrested for cannabis offenses.9 Such disproportionate policing is ideologically reinforced by the legal transition to “recreational” cannabis, which, disarticulated from medical justifications, retains the stigma associated with cannabis under prohibition, particularly when operating “underground.”

Meanwhile, Oakland, Los Angeles, and other California cities have instituted social equity laws that, among other things, provide preferential access to licenses for growing and distributing cannabis based on an applicant’s past cannabis convictions; history living in a community disproportionately impacted by the war on drugs; or identity as a woman or veteran.10 At the state level, the California Department of Cannabis Control employs a Deputy Director of Equity and Inclusion which waives licensing fees and provides technical support for navigating the licensing process.11 Such regulations have met with limited success in diversifying the industry since high start-up costs, as well as the costs of complying with state regulations, exclude most working-class Black and Latinx people from owning a licensed grow facility, retail dispensary, or distribution company.12 Hence most owners in the industry are white.13

Cannabis Social Equity and the Marketing of Diversity

Building on the practice and theory of social equity laws, however, a small number of Black and Latinx cannabis companies are thriving in California, where they market cannabis with images of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Latinx cannabis companies include Dr. Greenthumb, a vertically integrated company (with its own clothing line) founded by rapper B-Real from Cypress Hill; the Backpack Boyz, another vertically integrated company owned by MMA fighter Juan Quesada; Ciencia Labs, founded by Carolina Vazquez, which markets “Luchador,” a line of cannabis infused gummies in Mexican flavors like pitaya and chili lime (the company stages free Lucha Libre matches at dispensaries and other venues); Humo, whose slogan is “Craft Grown, Raza Owned,” led by brand partner Susie Plascencia, who markets cannabis strains with names like “Cajeta” and “Pulque”; Dope Flavors from the Bay Area, a company that sells a strain named “Dr. Che,” after Che Guevara; Loopy Sanchez, whose advertising slogan is “Barrio Grown”; and POLA, which markets the cannabis-infused beverage brand Agua de Flor and a line of cannabis infused chocolates called La Familia.14

Jay Z’s Monogram, the biggest Black-owned cannabis company in California, brands cannabis as part of a luxury “good life,” while also emphasizing equity. Monogram employs acclaimed grower Deandre Watson as Culture and Cultivation Chief at the company’s massive San Jose warehouse. Watson, who was previously arrested for growing cannabis, claims:

We all know that the War on Drugs disproportionately victimized people of color and I am one of those people. It was a major challenge to break into legal cannabis. I never thought it would be a legitimate business and I’m blessed to be living a dream that I never even dreamed. Working with Monogram has been so fulfilling because of what we’re doing to increase social equity within this industry. That starts with creating more above-board opportunities for people like me.15

On a smaller level, University of California, Berkeley graduate Chris Ball from Rialto, California, successfully applied for social equity licenses to grow and distribute cannabis for his company, Ball Family Farms around 2014. Before that, he had been arrested by the DEA for distributing cannabis across state lines and spent months in jail. Ball now markets cannabis strains named after Black film characters such as “Laura Charles” (The Last Dragon) and “Nino Brown” (New Jack City).16 There are also dispensaries that use representations of Black feminist icons in their marketing. The South Central Los Angeles dispensary called “Josephine & Billie’s” was founded by Whitney Beatty under a social equity license in 2021. Focused on women of color cannabis consumers—especially Black women—the dispensary is named for Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday who feature prominently in the company’s branding. As the dispensary’s mission statement explains, “Our name pays homage to Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday, two women of color who were persecuted for their cannabis consumption and yet used their art to fight against injustice, rejected the mainstream, made their own rules, and most importantly, held the door open for other women who will come after them.” 17 The dispensary has attracted investments from Jay-Z. Finally, the Los Angeles dispensary chain called Sixty-Four & Hope is owned by Aja Allen and Rhavin Klein under equity licenses supported by investments from Queen Latifha and Nas, with plans to open a total of 21 such dispensaries.18 Echoing social equity laws and discourse, these entrepreneurs brand cannabis in DEI terms.

The largest force for commercial, DEI cannabis in California and the world is the Cookies Company, founded by Latinx rapper Berner, the stage name of Gilbert Anthony Milam, Jr. Profiled in Forbes in 2022, Milam grew up in San Francisco, where his father managed a Mexican restaurant, before moving to Arizona. His company is vertically integrated, producing, distributing, and selling cannabis in its chain of 40 storefront dispensaries in several US states as well as in Israel, Spain, Portugal, and Thailand. There are 22 dispensaries in California—Southern California and the Bay Area, but also throughout the San Joaquín Valley. The Cookies Company is inspired by and employs Latinx and Black multicultural, urban imagery reminiscent of Sesame Street, as suggested by its ubiquitous baby blue branding, the color of Sesame Street’s beloved Cookie Monster. Because it remains illegal at the federal level, cannabis is a cash industry without ready access to credit and financial institutions. While this creates difficulties for everyone in the industry, it produces special barriers for Black and Latinx people. As one anonymous Black cannabis entrepreneur explained:

You will not get into this industry if you are black and do not have a $1 million. Good luck finding an investor who is not a predator. We cannot go into a bank and get a business loan because cannabis is illegal on a federal level. Limited access to capital has nothing to do with not knowing where to get money or having no money available. Many investors, even black ones, look at us as a risk because of our race.19

As a work around, Berner discovered that while weed can’t be copyrighted, other Cookies products could, so the company began to market a line of clothing, bags, and accessories. As Berner told a video blogger in 2021, the Cookies clothing line alone earns $55 million a year.20

Berner markets both clothing and cannabis with ideas and practices of diversity. Like other Black and Latinx growers and distributors, “equity” is one of his keywords, foregrounded on the company’s “social impact” web page, titled “Stronger, more equitable communities through cannabis.”21 As he told Forbes, “Black and brown communities set trends. It’s important to realize that our personality and our aura brings a lot to the table…So make sure you get your equity, that your value is recognized. Use your aura to get through the door and work with someone, and work hard. And get equity, ask for something that can last forever.”22 Berner here uses the term “equity” to explain the commercial value of POC culture: because people of color set cannabis trends, they should have a share of cannabis wealth. These ideals regarding equity inform Berner’s “Cookies University,” a Humboldt County summer school introducing working-class Black and Latinx students to the cannabis industry. The school is on the site of a historic road-side attraction on Highway 101, “The One Log Tree,” a giant redwood tree that was hollowed out in the 1930s and turned into a tiny house (Figure 5). The refunctioning of a former logging attraction as part of a cannabis attraction suggests the extent to which cannabis has replaced logging as the region’s most important industry. Berner bought the property, including the log house (which visitors can tour for a nominal fee), and built a gift shop, dispensary, consumption lounge, outdoor cannabis farm, underground genetics library, and classroom (Figure 6). Students live there in modern, tiny houses (Figure 7).

Figures 5–7. Sign for Berner’s One Log cannabis complex in Humboldt County, A-frame sign for the One Log Cookies Dispensary, and tiny houses for “Cookies U.” Photos by author.

Cookies U echoes equity licensing laws. To be eligible for admission, applicants must meet one or more “social equity criteria,” such as cannabis arrests, low income, housing insecurity, homelessness, US military service, or being a woman, person of color, and/or an LGBTQ+ person who has worked in the cannabis industry. The school graduated its first class of four in summer 2022. Cookies U was advertised with a half hour video, widely circulated on social media, documenting the CEO’s visit to the school and his meeting with students.23 The company also maintains three Instagram accounts devoted to the summer school and other “social impact” programs.24 And Berner plans more schools in Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York City.25 In these ways, Berner’s company has rearticulated the language of social equity for marketing. The company even markets what it calls “social impact” strains such as Cake Mix, advertised with the stylized image of a woman of color smoking a joint. In his analysis of Colorado, Marty Otañez argues that the social responsibility programs of cannabis corporations can become forms of “greenwashing” that distract from questions of worker wages and health and safety.26 Most jobs in the cannabis industry are low wage and unregulated. Employee comments on job review websites such as glassdoor.com and indeed.com complain about the lack of job security and prospects for promotion, and that the Cookies Company seems to put profits over people.27

In his Forbes interview Berner suggests that cannabis is a racialized product that radiates Black and brown “auras,” indicating that the success of the Cookies corporation is partly based on the appropriation and commodification of racial identities.28 The Instagram account for its flagship clothing store in San Francisco includes images of lowrider cars and bikes; rappers with tattoos, grills, and oversized medallions; and attractive young Black and Latinx men and women in Cookies clothing. While not always the case, the young women are often dressed in revealing ways, emphasizing a conventionally gendered appeal to consumers. While usually wearing more clothes, however, the young men of color in Cookies ads are also eroticized, offered up to the viewer as attractive product spokesmodels. The sensual appeal of the company’s marketing is in keeping with a longer history of commodity aesthetics. As Wolfgang Haug writes in Critique of Commodity Aesthetics: Appearance, Sexuality and Advertising in Capitalist Society,

a whole range of commodities can be seen casting flirtatious glances at the buyers, in an exact imitation of or even surpassing the buyers’ own glances, which they use in courting their human objects of affection. Whoever goes courting makes themselves attractive and desirable. All manner of jewelry, fabrics, scents and colors offer themselves as means of presenting beauty and desirability. Thus, commodities borrow their aesthetic language from human courtship; but then the relationship is reversed and people borrow their aesthetic expression from the world of the commodity.

Haug concludes that in commodities, “powerful aesthetic stimulation, exchange-value and libido cling to one another,” and I would add race to that mix since Cookies appeals to consumers by eroticizing Black and Latinx styles and identities.29 The company effectively sells Blackness and brownness to both white consumers and consumers of color.

Teds Budz: Selling the Working-Class Good Life

The small Los Angeles based company Teds Budz, founded by Theo “Ted” Lewis, is named after Lewis’s grandfather and namesake, whose disapproving cartoon face appears on its logo, product labels, promotional materials, and even the tattoo on Lewis’s left arm (Figures 8–9). Raised in Omaha, Nebraska, the younger Lewis relocated to southern California over a decade ago. At that time, he began turning distressed houses into boarded-up grow spaces. In 2015, he was arrested for running an illegal dispensary and growing facility, barely avoiding federal prison. Lewis attended California State University Northridge as a Black studies major; when we met in summer 2022, he was reading Malcom X. Aware of his college background, I gave him a copy of my book, Drug Wars: The Political Economy of Narcotics; he’s half my age and interacts with me like someone who has talked to professors before. Later I learn that Lewis promoted his cannabis events on a podcast by saying “You got gang members coming out, cholos coming out, professors coming out.”

Figures 8–9. Theo “Ted” Lewis (right) posing with a fan (left) at a Teds Budz event at a dispensary in the industrial, working-class Latinx city Maywood, in Los Angeles County. An image of Theo Lewis’ grandfather and namesake on a cannabis package. Photos by author.

Lewis’s ambition to distribute legal cannabis was shaped by his working-class Black background and its disproportionate vulnerability to policing and incarceration. As he told LA Weekly, “The cannabis industry is saturated with trust fund kids who have not had to risk their lives in order to see this opportunity . . . . After I found out how social equity opportunities were being stolen from the true grassroots entrepreneurs I attended town hall meetings, protests, and audits for different rounds of social equity licensing.”30 When I interviewed him, Lewis told me he was a cannabis distributor and no longer a grower because the equipment for indoor grows is too expensive: “Sorry I don’t have rich parents, none of that shit, to help me fund a grow . . . . LED lights two Gs a piece.”31 His arrest made him eligible for an equity license and Teds Budz was incorporated in 2020. “I’m glad it worked out this way” he told me, “or I could be dead or in jail.”32 The company distributes cannabis from several growers, including Black, Asian, and Latinx producers.

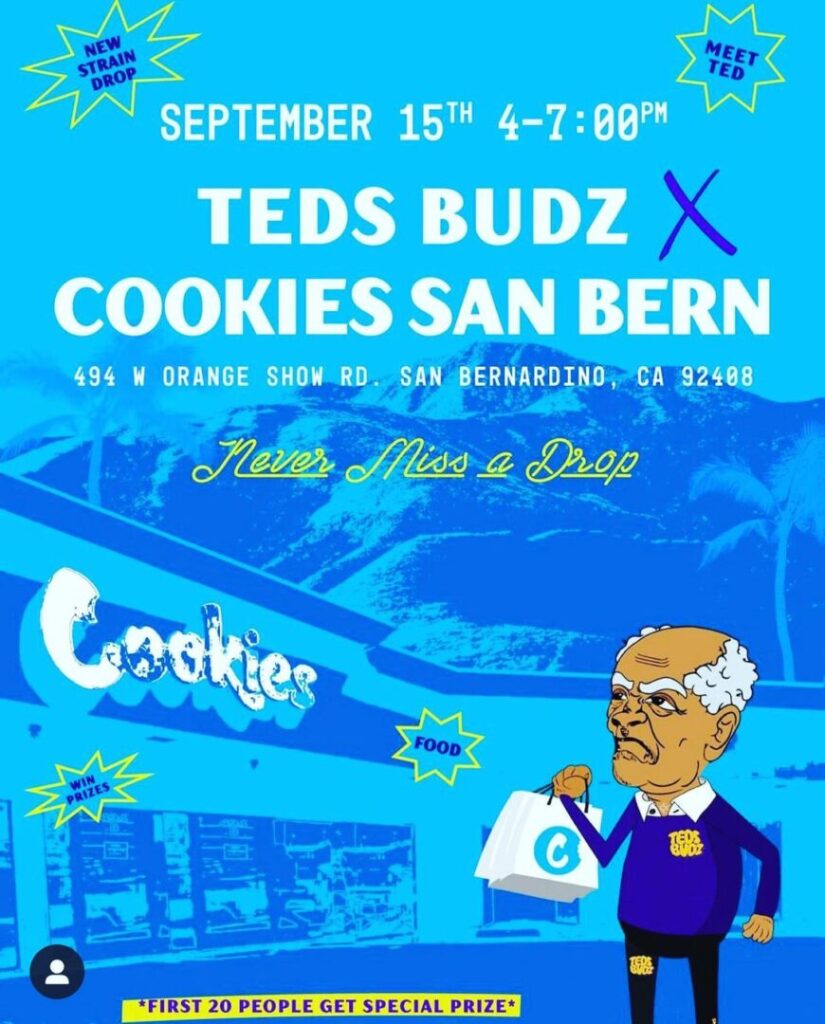

The distribution routes for Teds Budz map working-class Black and Latinx California. Social media announcements about new drop locations include relatively wealthy places like Los Angeles’ Melrose Avenue and West Hollywood, and San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury, but also many other, more precarious places in the state—working-class Black and Latinx towns and cities in the Inland Empire, South LA, East LA, and the San Joaquin Valley. Teds Budz has hosted in-store events at dispensaries in Southern California (San Bernadino, Maywood, Long Beach, La Mesa, Riverside), the Central Valley (Fresno, Modesto, Sacramento), and Oakland. At the six events I’ve attended, the other customers were mostly young, working-class Black and Latinx cannabis enthusiasts, the majority men but with significant numbers of women. Teds Budz events are formally different than those of most other companies, which often send a single employee with a table and some samples to a “patient appreciation day” event organized by a dispensary. Lewis and his staff put on much more elaborate events, and they discovered that when Lewis was present, many more people would come out to meet the charismatic distributor.33

Fall 2022, I saw an Instagram invitation for a Teds Budz meet-and-greet at a dispensary called “Cookies San Bern” in San Bernadino, a city that’s 12.6 % Black and 68% Latinx, with over 30% of its population living below the poverty line (compared to the national average of 11 percent)34 (Figure 10). It’s over 100 degrees Fahrenheit when I arrive at a strip mall just off the freeway in a busy commercial area. I’m half an hour early for the 4 p.m. event but there’s already six enthusiastic young brown people waiting in the punishing Inland Empire sun: four boys and one couple, the girl with braces on her teeth. One kid looks like a brown version of Dustin from the TV show Stranger Things, but with a nose ring, a Teds Budz T-shirt, and a biohazard-orange trucker hat. He works security somewhere nearby, and everyone seems to know him. People in line talk knowledgeably about recent Teds Budz drops, which can sell for over $70 an eighth with taxes. They seem to spend a lot on cannabis, which partly explains the party vibe, in expectation of free weed, free food, and swag.

The line is soon joined by two Latinos dressed cholo style. One is a handsome young man who could have been a Calvin Klein model back in the day. His friend is a little older, with a shaved head, goatee, and neck tattoo, and he parks a baby blue Mustang in the strip mall lot with a sticker across the top of the windshield reading “Mike’s Stang.” Impatient for the event to start, they smoke a joint in the car. Filling out the line is a young Black woman wearing a black baseball cap with the word “Issues” stitched on it in white; another Black woman passing out flyers for her upcoming art show; a young Black man with dreadlocks in a wheelchair; and a big friendly white guy wearing American flag Crocs. Most people look under 30, so I’m the oldest person in line.

A Cookies San Bern worker tells us Ted’s stuck in traffic and offers everyone branded lighters or bandannas while they wait. Ted’s staff arrives around 4:30, including his graphic designer Jacqueline Wallace, a photographer/videographer, and Ted’s partner Anthony Garcia. They buy bottles of water from the 7-Eleven next to the dispensary and hand them out to the crowd. Next, the “All Flavor, No Grease” food truck rolls into the lot and tickets for free tacos are distributed. Ted arrives shortly after, with the Black Thai rapper from Detroit named Eastside Eggroll, his collaborator on a new strain called “Duck Sauce.”

As Ted sets up, the line is hustled into the Cookies San Bern worker break room, where everyone is given a pink post-it with a number. The first twenty people are eligible for a “BOGO” deal—buy an eighth an ounce of cannabis and get a second free. On entering the showroom, customers spin a wheel for prizes, including branded hats, shirts, sweatpants, and of course cannabis. Ted signs them all and poses for pictures. Singly and in groups, young Black and Latinx people exit to the parking lot as the sun mercifully begins to set and Friday night begins. The event was memorialized in a Teds Budz Tik Tok video (Figure 11). It reminded me of collective working-class pleasures like rent parties, carnivals, and barbecues. Which is to say that Teds Budz at Cookies San Bern fed Black and Latinx desires for “the good life,” a world of freedom and plenty beyond existing restrictions and privations.

In its day-to-day operations, Teds Budz projects a working-class identity. The company is in an industrial section of the Latinx neighborhood of Boyle Heights, in a small warehouse that formerly housed a Korean clothing manufacturer. Most of the staff is Latinx or Black, including Lewis’s mother, who works on accounts receivable, and his sister, who works in the packing room (Figure 12). Seven people work there weighing, packing, and labeling cannabis. Also on staff are the previously mentioned photographer/videographer and graphic designer Wallace who works on promotional art, the Ted Budz clothing line, and the company’s social media, as well as a compliance officer (Figures 13–14). The workers at Teds Budz thus resemble the people who smoke Teds Budz. Lewis self-consciously pitches his products to working-class Black and Latinx consumers, who, he argues, drive cannabis trends in the state. He and his staff recently traveled over five hours to Modesto because the city with the large, working-class Latinx population is California’s largest consumer of Teds Budz. Reflecting a similar working-class constituency in Southern California, Lewis promotes “stash n dash” events where he posts videos of himself on social media hiding a bag of cannabis in an urban location and then posts a subsequent video when someone finds it. As Lewis explained to me, he only does that in “ghetto” neighborhoods, because “Brad and Chad don’t need free weed.” He insists “I’m not bougie” and believes he’s been successful partly because he comes from the same “demographic” as his customers. “I feel like I do speak for the black and brown, the streets in general, what people want, because I’m just like them.”35 As a result, growers ask him to evaluate the potential appeal of different strains for the Black and Latinx market.

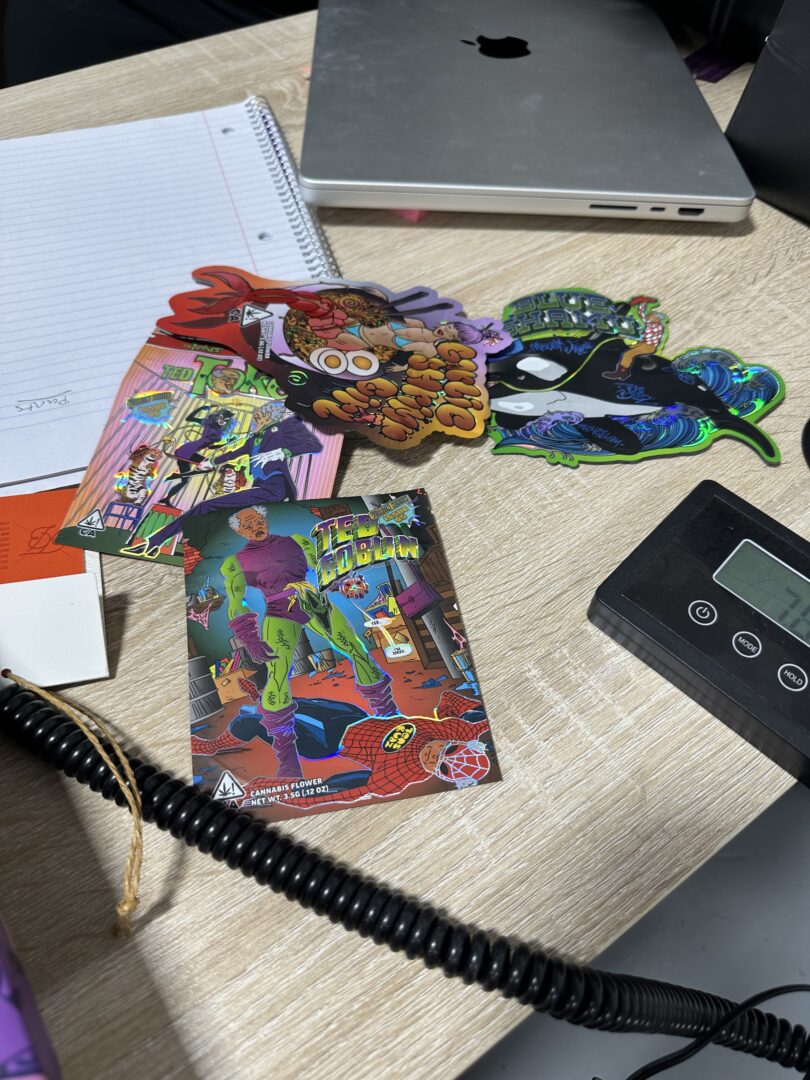

Figures 12–14. Graphic design and packing rooms in the Teds Budz warehouse. Desktop with packages for forthcoming strains, including “Blue Shamu,” featuring Grandpa Ted riding a killer whale. Photos by author.

This thriving cannabis scene is represented in eye-grabbing cannabis packaging, with different designs and imagery reflecting regional and demographic differences in production and consumption. Some cannabis branding is implicitly white and directed at white consumers as the default, while other branding is marked as Black and/or Latinx. Examples of the former are brands in white jars that resemble Apple designs, with intimations of high-tech efficiency that have historically been associated with white masculinity. Dispensaries that specialize in those brands incorporate elements of “white” interior design in their showrooms such as earth tones, reclaimed wood, and digital tablets at product viewing stations reminiscent of Apple Stores (Figure 15). These elements of interior design were well represented in the TV sitcom titled Disjointed (Netflix, 2017–18) featuring a dispensary called “Ruth’s Alternative Care” owned by a white boomer hippie and medical cannabis activist played by Kathie Bates. Modeled on a real dispensary in West Los Angeles, Ruth’s Alternative Care is brightly lit, with stained glass windows and blonde wood bars and display cases. Meanwhile, Ruth’s competitor, “Bud, Bong and Beyond,” features white tablets on wood display tables, as well as a “Greenius Bar” in imitation of Apple’s “Genius Bar.” The “white” dispensaries that inspired Disjointed often don’t sell the Black and Latinx brands that are the focus of this essay.

The container of choice for Teds Budz and other Black and Latinx cannabis brands is the mylar bag. It’s an inexpensive material for making resealable packages that are lighter and easier to transport than glass jars, and which take up significantly less warehouse space. Mylar bags are also an aesthetic medium, covered in images like tattooed bodies or luxury fashion goods. The interiors of Teds Budz bags are often embossed with thematic images or grower logos, while bag exteriors are sometimes covered in ornate “TB” monograms and cross hatching that mimic patterns on designer handbags, symbols of the good life. The fronts and backs of mylar bags are also used as surfaces for elaborate art aimed at working-class Black and Latinx consumers. Lewis collaborates with graphic designer Wallace, and sometimes his tattoo artist, to design the packages. A fan of anime and other cartoons, he’s an avid sketch artist, who tries out ideas on whiteboards and on walls in the warehouse media room where he spray-paints murals (Figure 16). Lewis shares sketches with Wallace, who realizes the final version, but often after much back and forth. He showed me images on his phone of multiple drafts of the art for the strain “Big Squid,” for example, featuring a cartoon squid riding a surfboard.

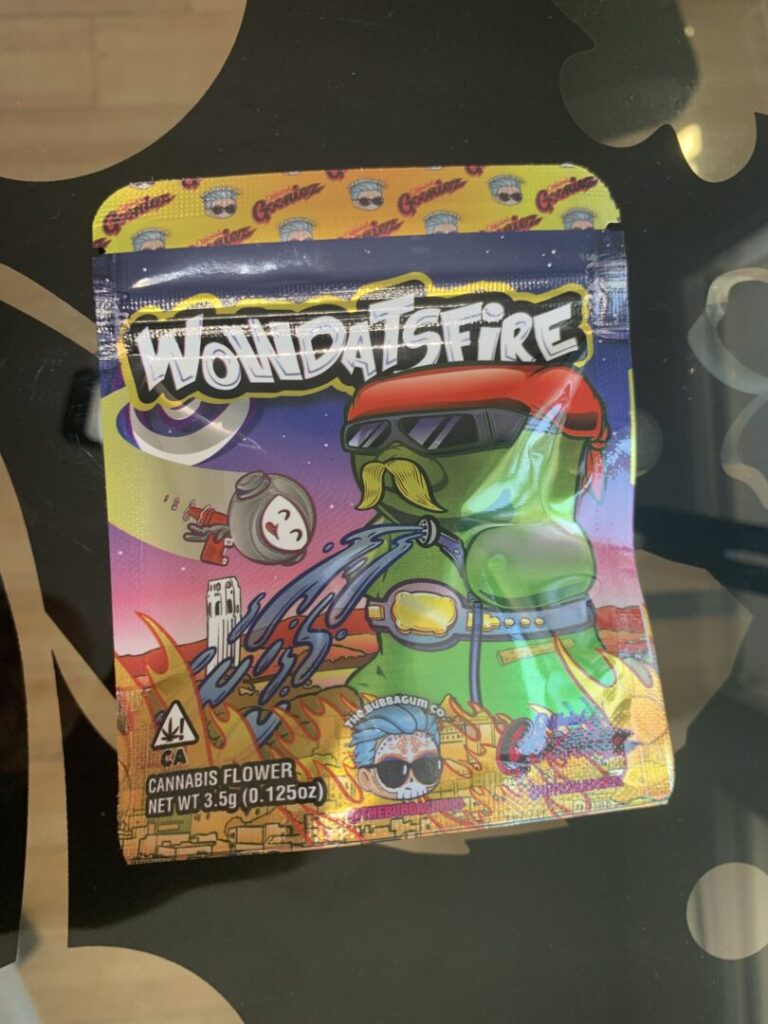

Cannabis labels represent Black and brown working-class life not with realist images but in fantastic forms. The label art for the Teds Budz distributed strain called “WowDatsFire” depicts a cartoon Latinx landscape worker spraying water from a hose on a fire raging across an urban landscape (Figure 17). “Fire” is one of the most common honorifics applied to good cannabis both verbally and graphically, as in the “fire” emoji on Instagram. Many Latinx people in Southern California also work in fire abatement, removing weeds and other debris to protect homes and businesses.36

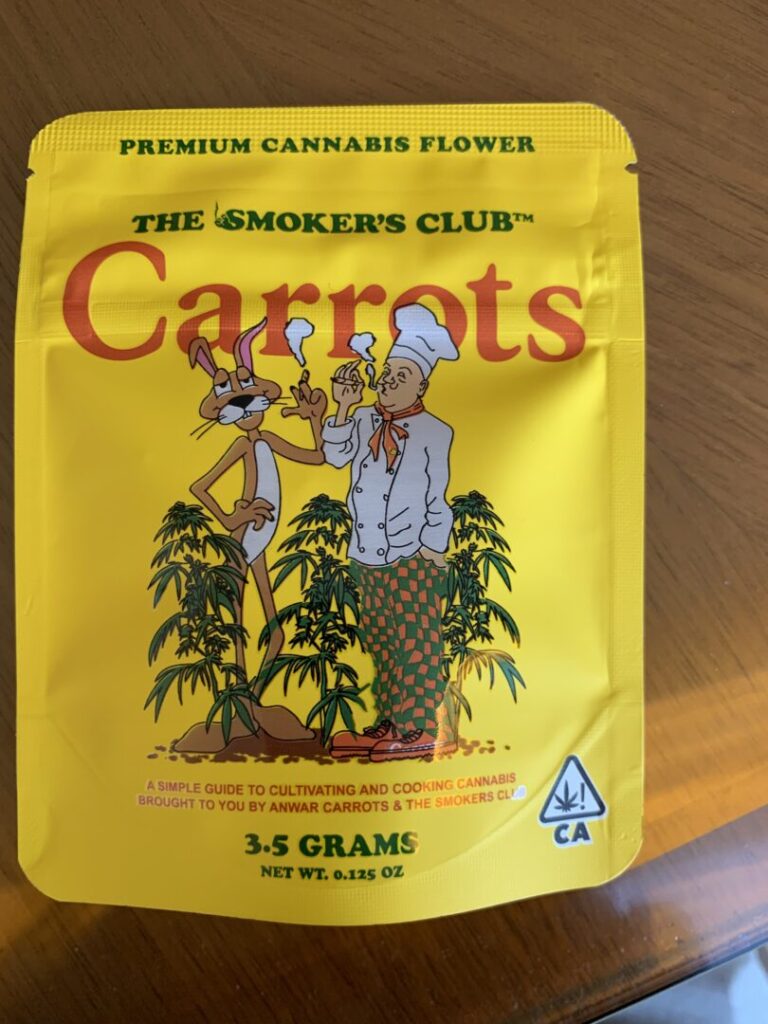

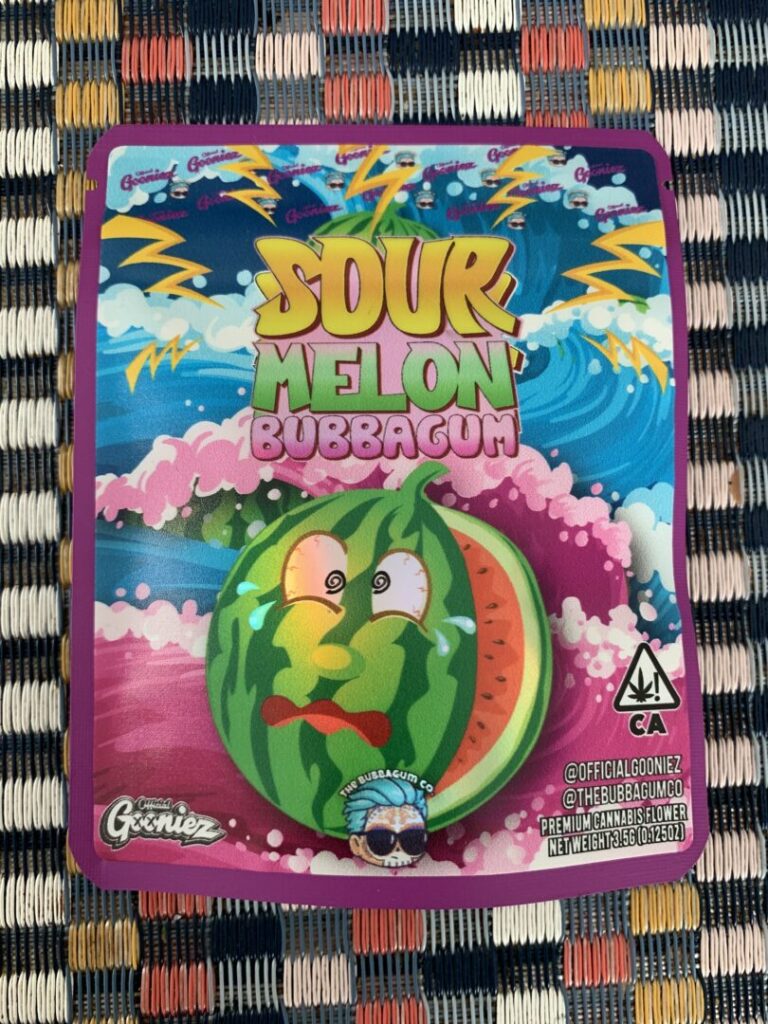

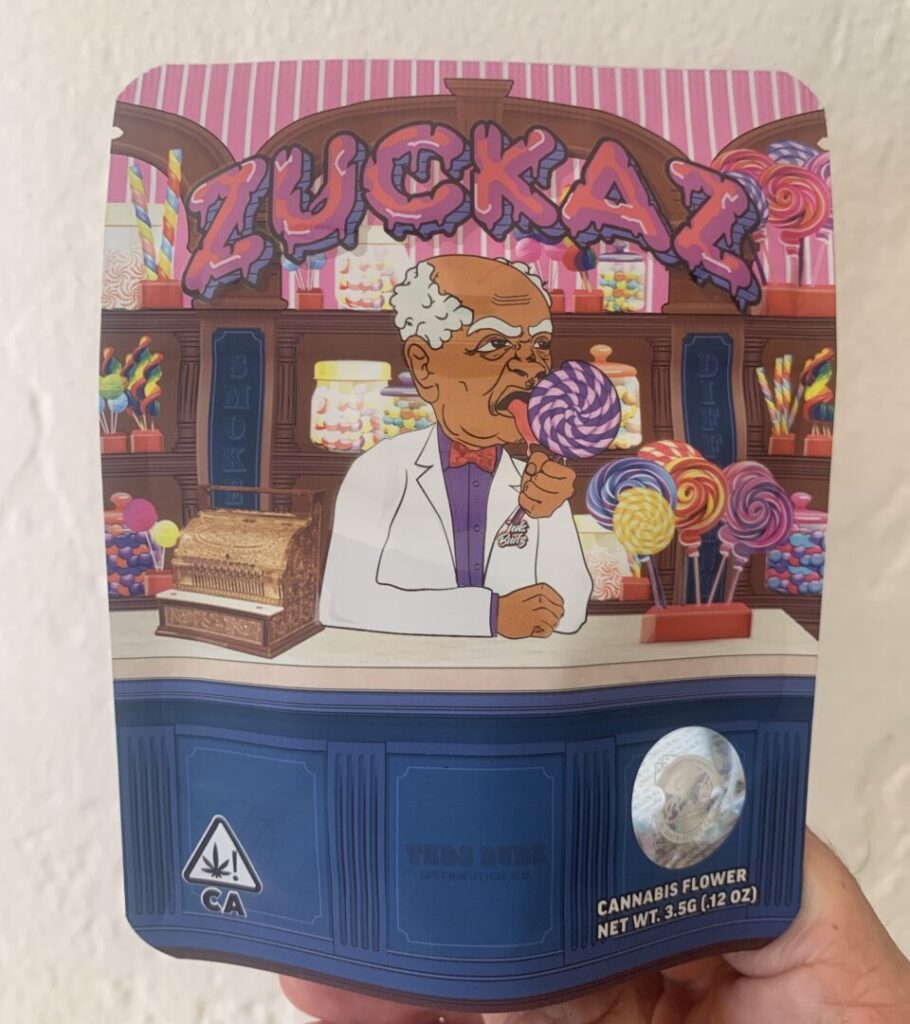

The package for the strain “Carrots” similarly features a cartoon representation of food service: a giant rabbit and a restaurant worker both smoking blunts (Figure 18) Many other packages promote fruit flavors with images reminiscent of California fruit labels and the history of Latinx farm labor behind them, as in the mylar bags for “Sour Melon Bubbagum [sic]”37 (Figure 19). Another occupation is depicted on the “Zuckaz” strain label, where Grandpa Ted appears as a salesperson in a candy store (Figure 20).

Figures 17–20. Cannabis packages representing a landscape worker and a food service worker, recalling historic labels for produce harvested by farm workers, and depicting Grandpa Ted as a retail worker. Photos by author.

Black and Latinx consumers and their family members and friends may well have worked in landscaping, food service, farm labor, or retail, making cannabis labels imaginative reflections on their own labor histories. My final example of a fantastic depiction of work is the package for the strain Z-Rilla, depicting a green zombie in blue jeans and a blue work shirt over a white t-shirt. The label humorously teases the powerful effects of the cannabis inside (the zombie’s exposed brain suggests comparison to Cypress Hill’s stoner anthem “Insane in the Membrane”), while also referencing the history of zombies as representations of workers of color (Figure 21). Such packages take for granted that cannabis consumption is integral to Black and Latinx working class life.

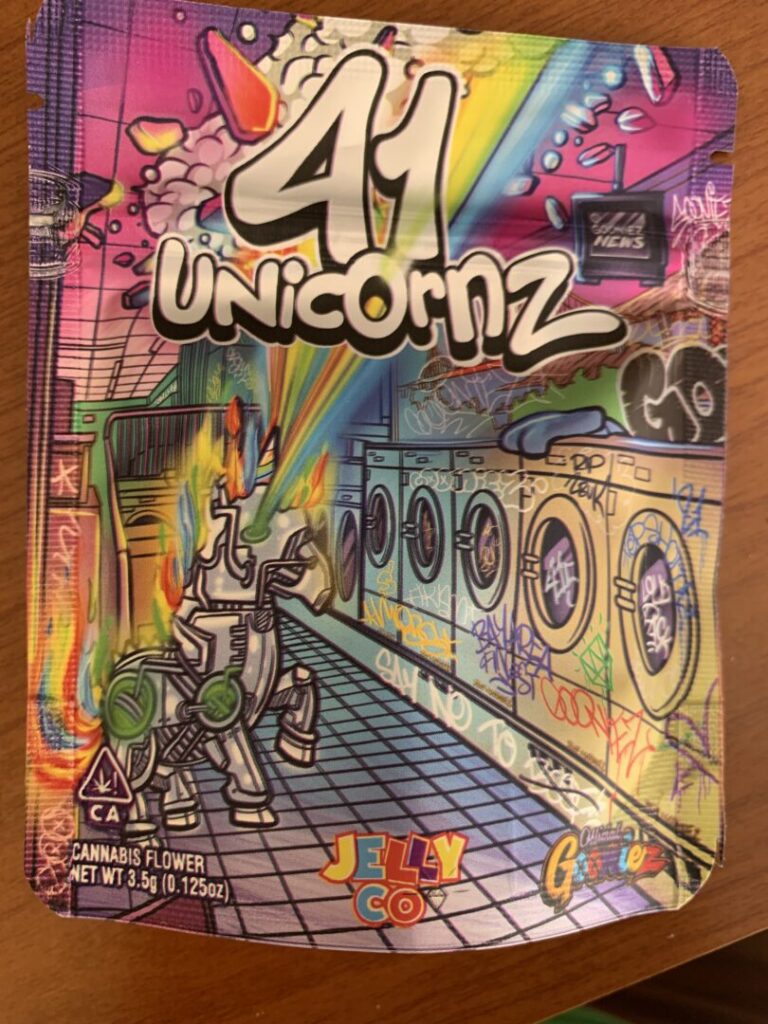

Cannabis labels further appeal to consumers with fantastic representations of mobility that contrast with the limits of working-class realities. The label for the strain “Ultra Slushers” depicts Black and brown figures flying over a cityscape, leaving rainbow trails in their wake. The package for the strain “Milky Belts” similarly features Grandpa Ted flying a colorful retro rocket into space. The bag for “41 Unicornz” combines a familiar working-class setting—a graffiti-covered laundromat—with a unicorn that blasts rainbow rays through the roof (Figure 22).

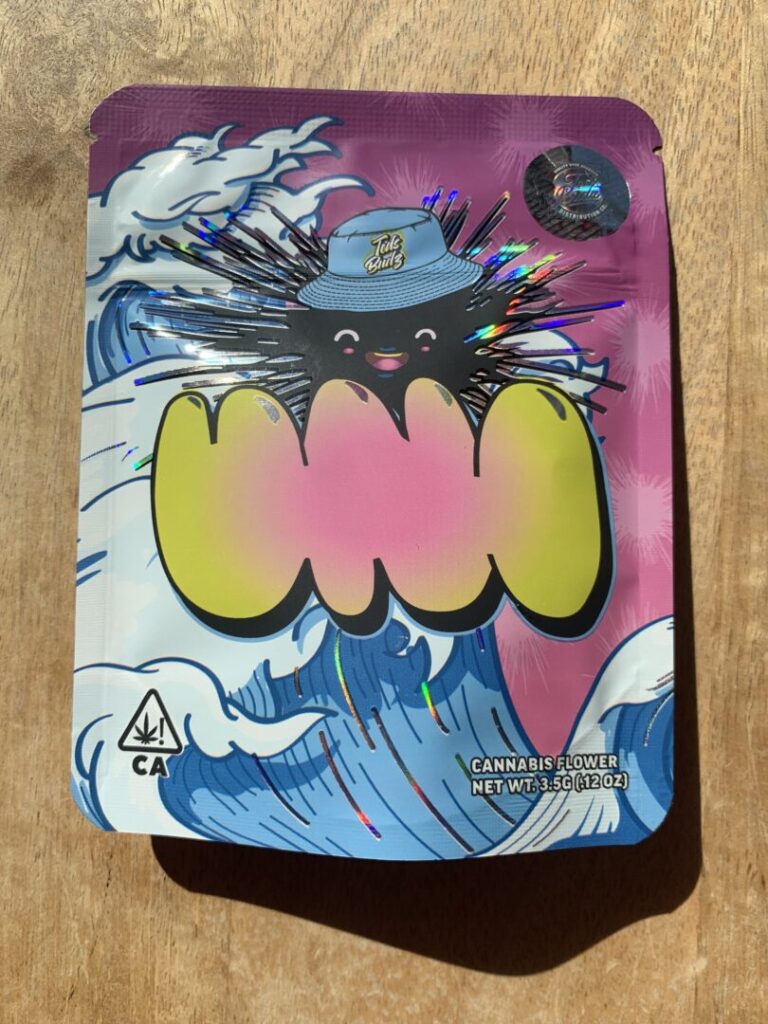

Figures 22–23. Cannabis packages with a unicorn blasting a rainbow opening out of a laundromat and a black anime sea urchin riding a wave. Photos by author.

Part of a “deep sea” series, the package for “Uni” depicts a smiling, spiny black sea urchin, wearing a blue “Ted’s Budz” hat, riding high on an ocean wave as the sun sets (Figure 23). Similarly, the bag for “Blue Shamu” features Grandpa Ted dressed as a cowboy, riding a killer whale. A few packages riff on comic book characters with superpowers of mobility such as “The Fastest Man Alive: Ted Flash,” with an image of Grandpa Ted dressed as the Flash dashing through a city street, the air pressure generated by his high velocity visible in the windblown hair and flying hats and ties of the pedestrians he speeds past; and “The Amazing Spidey-Ted,” represented by Grandpa Ted, costumed as Spiderman, swinging by a web through a city skyline.

Finally, several packages depict a romanticized Buick Grand National car, which also appears on the company’s website and other promotional material (Figure 24). In auto-dominated Southern California, such a vehicle represents freedom of movement. Lewis himself is the proud owner of a black Grand National, which he features in his videos. Working with his graphic designer and manufacturers in the downtown LA garment district, he also designs and sells a line of racing jackets. A common genre of photos on cannabis Instagram are taken from inside cars, where consumers fresh from the dispensary display their new purchases. The focus on cars as symbols and settings compliments the use of the word “gas” to describe the desirable taste, smell, and effect of cannabis strains. As Lewis confirms, Black and brown consumers in California demand a “gassy” flavor profile. Such cannabis has also been described as tasting like “jet fuel,” which, like “gas,” suggests its utopian powers of transport beyond the material limits of the here and now. In response to the challenges that working people of color face both in terms of physical mobility (the cost of transportation; racial profiling by the police) and class mobility (the stratified labor relations of contemporary racial capitalism) fantastic images of flight, driving, and even surfing entice consumers with powerful promises of freedom.

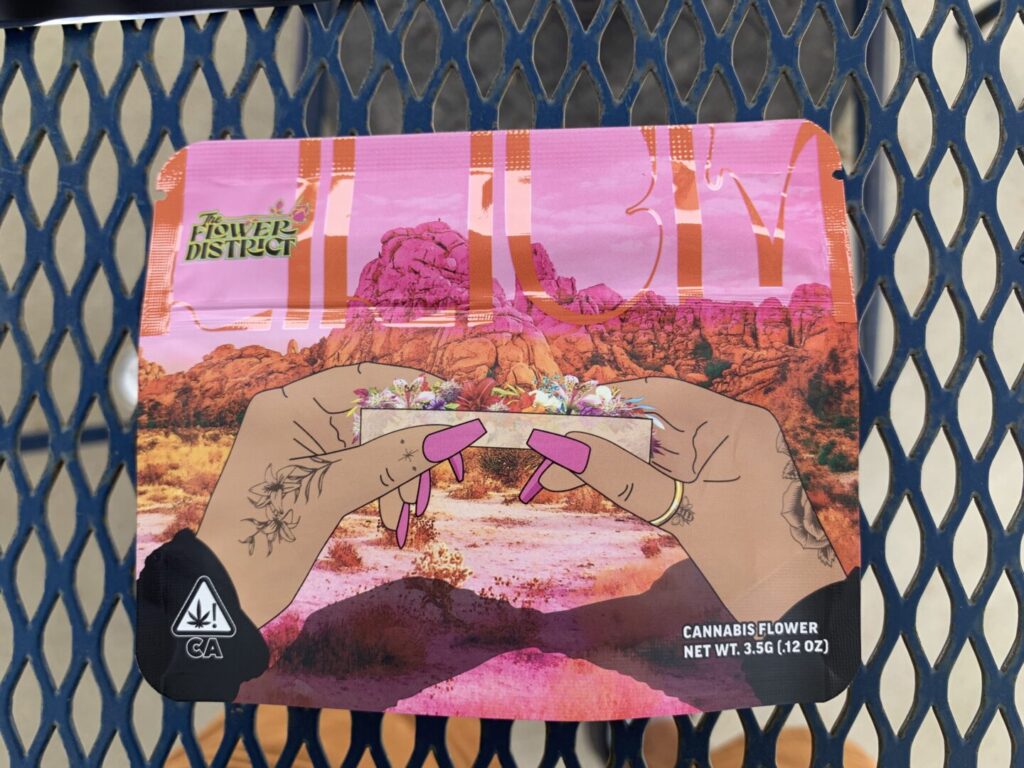

The Teds Budz related brand called “The Flower District,” is named after the Flower District in downtown Los Angeles where Latinx wholesalers and workers sell flowers harvested in California, often by Latinx farmworkers. The line is produced by Lewis’s partner, Anthony Garcia, who remembers his family’s visits there38 (Figure 25). Cannabis buds are the cured flowers of the plant, and Flower District strains were initially packed in pink bags embossed with roses and named “Primrose,” “Lilium,” and “Dahlia.” As Lewis explained in an Instagram video, the package has a unique design, with a wide opening that’s easier for hands with long nails to reach into. Flower District art reinforces this point by representing brown hands with long pink nails rolling a joint of flowers against an Inland Empire desert backdrop (Figure 26). In film studies this would be called a point of view shot since the image is from the implied vantage point of the figure rolling the joint as they look at their work.

This presentation of the point of view of a working class woman of color is replicated in the Instagram video promoting the Dahlia strain. Filmed at sunset, at the Los Angeles County Fair in Pomona, the video echoes the carnivalesque pleasures on offer at the company’s dispensary events. It follows a group of young Black, Latinx, and white women, several of whom work at Teds Budz, as they walk through the midway, play carnival games, and smoke joints on an aerial tramway and a Ferris wheel. Among the women in the video is Wallace, the Teds Budz graphic designer who designed the Dahlia mylar bag. Their movements through the fair are stitched together with repeated shots of women looking at the cannabis package, and POV shots of the package held by hands with brightly colored acrylic nails, thus doubly representing a woman-of-color gaze and inviting viewers to identify with it. Reinforcing such identifications, in the final shots a fem Latinx young person offers the camera the joint she holds in her pink nails (Figure 27).

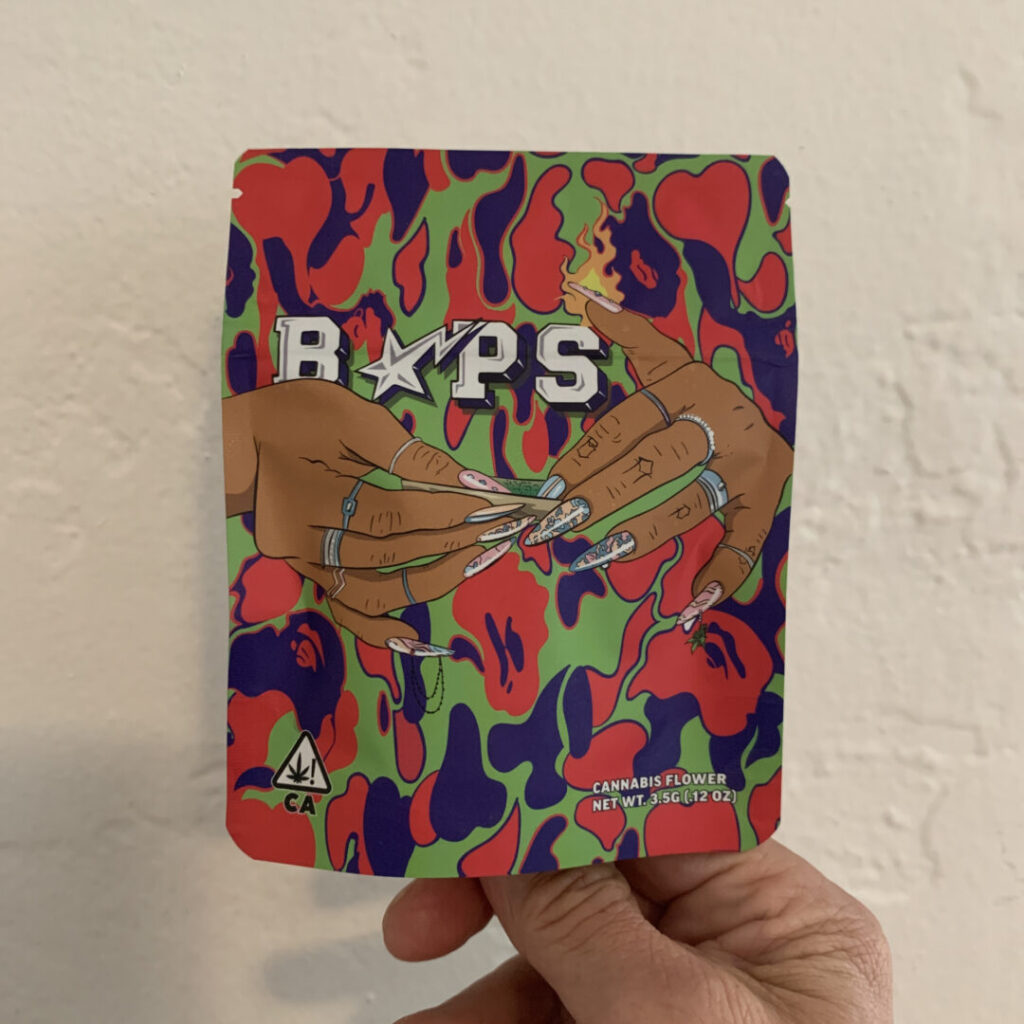

Finally, the sunset timing of the video entices with intimations of freedom. A summer sunset in the desert sky brings the relief of cooler weather but also twilight, that space in-between day and night symbolizing possibility, or what José Muñoz theorized as futurity, the open-ended desire for a world beyond the limits of the present. In all these ways The Flower District appeals to consumers by presenting a working-class woman-of-color vision of the good life. Dahlia anticipates the more recent package for another Teds Budz-distributed strain by Black Bay Area grower Cream City called “BAPS.” As the back of the package explains, BAP is an acronym for “Black American Pressure” (in canna-slang “pressure” is used to describe the effects of especially good cannabis), but it also refers to the phrase “Black American Princess” and the title of the film BAPS (1997), about Black waitresses from Georgia who seek their fortunes in Los Angeles. Ads for the BAPS cannabis strain include an artist’s image of Halle Berry in her BAPS film role, while the package features bejeweled Black hands with long acrylic nails rolling a joint (Figure 28).

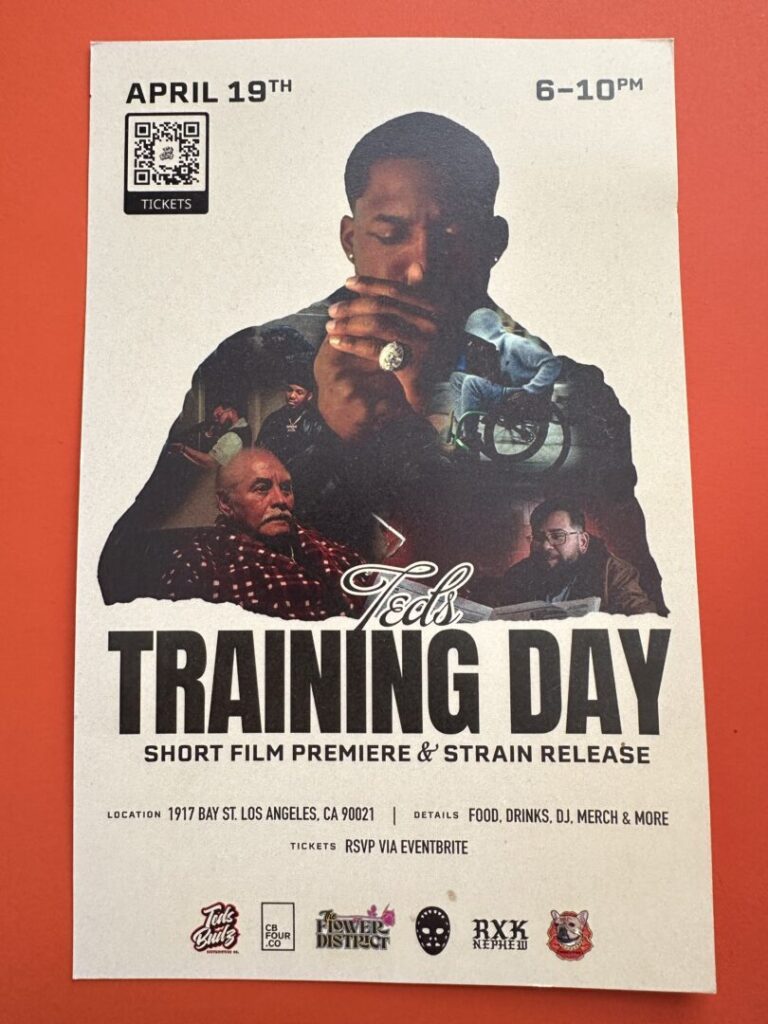

The juxtaposition of working-class life and the transcendence of its difficult or oppressive conditions further describes the promotional videos Lewis has made parodying popular movies and TV shows. In “Ted Montana,” Lewis plays a campy version of Cuban drug dealer Tony Montana from Scarface (Figure 29). In a Law and Order parody, he plays a detective investigating a case of “death by boof” (slang for bad weed). Ted returns to fighting boof in parodies of Batman and Game of Thrones (Figures 30–31). Meanwhile, a video inspired by Jordan Peele’s Get Out jokes about the difficulties of the working day with a skit about a pompous manager and featuring terrified reaction shots from workers (Figures 32). The videos are earnestly goofy, with decidedly low production values, filmed in the Teds Budz warehouse, and all roles are played by people who work there. White walls, exposed airducts, metal shelfing, packing tables, and employee lockers provide the contrasting setting for fantasy cosplay and comedy skits. Recently, Teds Budz even hosted a screening of their partial remake of the film Training Day starring Lewis, Garcia, and Garcia’s father (Figure 33). Such juxtapositions of work and pleasure, labor, and the good life, define the cannabis commodity aesthetics employed by Teds Budz.

Figures 29–32. Teds Budz parodies of Scarface, Batman, Get Out, and Game of Thrones (clockwise from upper left). Screenshots by author.

Scholars who study the history of drug use emphasize its incorporation into labor relations. Haug argues that “powerful stimulants” such as spices, tea, and coffee (I would add opium and coca) “have entered European history as instruments of merchant capitalist valorization.”39 Over time, however, western capitalism, according to Haug, required the “clear-headed bourgeois intoxication” of chocolate, tea, tobacco, and coffee. Others have drawn critical attention to drug use and colonial labor relations. Warf, for example, argues that cannabis supported British colonial power. Drawing on James Mill’s Cannabis Britannica, he argues that, from 1793 to the 1850s, the British East India Company profited handsomely from cannabis taxes and licensing fees in South Asia. In some areas, distributors were required to store cannabis in government-owned warehouses. Additionally, cannabis farmers were policed to prevent them from avoiding taxes.40 Anticipating the contemporary regulatory scheme in California, in colonial India cannabis generated tax revenues and helped anchor forms of state and corporate power.

Cannabis has also served as a painkiller, and a source of sustaining pleasure, that enables workers to work. Warf’s account of cannabis and British colonialism in the Caribbean provides a revealing lens for thinking about cannabis in contemporary California:

Drugs were important in several colonizers’ attempts to compel local populations to produce export goods vital to the world economy. Alcohol was (a) common labor pacifier in tropical plantations. In the 19th century, British authorities brought 1.5 million “surplus” laborers from India to labor-short islands in the Caribbean. Indentured Indian workers brought ganja with them to Barbados and Jamaica after the abolition of slavery there in 1834, and it was tolerated so long as sugar production did not suffer (Angrosino 2003). Ganja’s use was closely wrapped up with that of rum, so that the two drugs became intertwined in the cycle of work, debt, and poverty that characterized latifundial life on the sugar plantation, an excellent demonstration of colonial biopolitics.41

While different in so many ways, this historical example is a challenging template for understanding the contemporary context of legal cannabis in California. Historically, cannabis has oiled the wheels of state power and capitalism, providing revenue and profits; served as an alibi for state regulation and policing; and functioned as a kind of life support for laboring bodies that makes their exploitation possible. Legal cannabis has produced new jobs, but most of them are low wage work.42 At the bottom, migrant agricultural laborers are the most vulnerable to exploitation and the occupational health hazards of growing and processing cannabis.43 For workers both inside and outside the industry, cannabis dulls pain, relieves boredom, and provides a bit of pleasure.

In this regard, Teds Budz once again mirrors its working-class Black and brown consumers. When I arrive at the warehouse for our 10 a.m. interview, before we start Lewis briefly disappears saying “let me get a joint,” and he returns with a zeppelin. There’s no smoking in the warehouse, so we go out to the small entryway behind a rusted industrial screen door. I sit on a folding chair and he sits on a stool as he lights up, flicking ashes into a coffee can (Figure 34). For a moment I worry about what I will do when he passes it to me. How will I take notes and then drive back to my hotel? But that moment never comes, and he slowly smokes it down while answering my questions, pausing once to hit an asthma inhaler. When the joint was done, so was the interview. In keeping with the utopian, gifting culture of cannabis, Lewis then gave me a “Spidey-Ted” T-shirt and several mylar bags of weed. As I left I encountered a young brown woman worker from the packing room smoking a joint in the entryway. Despite stereotypes of the couch-locked stoner, in practice cannabis serves as a stimulus to work, with consumers debating which strains promote mental focus and energy for physical activity. These connections between work and cannabis are suggested by advertising. A 2020 content analysis of online product descriptions from retailers in six states (including California) found that cannabis was most often promoted for stress relief; for focus, energy, and productivity; and for pain and depression.44 The painkilling and pleasure-producing effects of cannabis enable workers to reproduce their labor power through cannabis recreation. It is similar to vehicles of transport, which also take Black and brown people to work. One Teds Budz packing room worker, for example, regularly posts Instagram videos of their drive to and from the warehouse. Transport can also be dangerous. Lewis used to drive to Oakland weekly and told me about an incident where San Joaquin Valley police confiscated his cash, cannabis, and laptop. Studying cannabis commodity aesthetics thus makes visible the contradictions between work and the good life, drawing critical attention to the gap between where working-class Black and Latinx people want to be and where they are now.

Cannabis Futurity

Cannabis sustains Black and Latinx lives and freedom dreams that draw into critical relief the material limits of the present while also incorporating Black and Latinx consumers and workers into racial capitalism. Such contradictions will remain so long as the material conditions that help produce them remain, making the abolition of racial capitalism the horizon of futurity for cannabis users and so many others. Among other things this would mean abolishing the racialized criminalization of the so-called “black market.” But in the meantime, how can cannabis culture be made less damaging and more sustaining for Black and Latinx cannabis workers and consumers?

Like other US states, California legalized cannabis on the commercial model of alcohol, whereas a variety of non-profit regimes, including state monopolies, could have been pursued instead. While it would bring its own challenges and problems, a state monopoly on cannabis sales would remove the profit motive.45 If treated like a public good and provided at lower cost, cannabis would be a more affordable support for Black and Latinx working-class lives. But since legalization, the cat is out of the mylar bag, and, recalling alcohol lobbyists, the corporate interests behind commercial cannabis have more money and hence influence over how cannabis is sold than any possible advocates for non-profit weed.

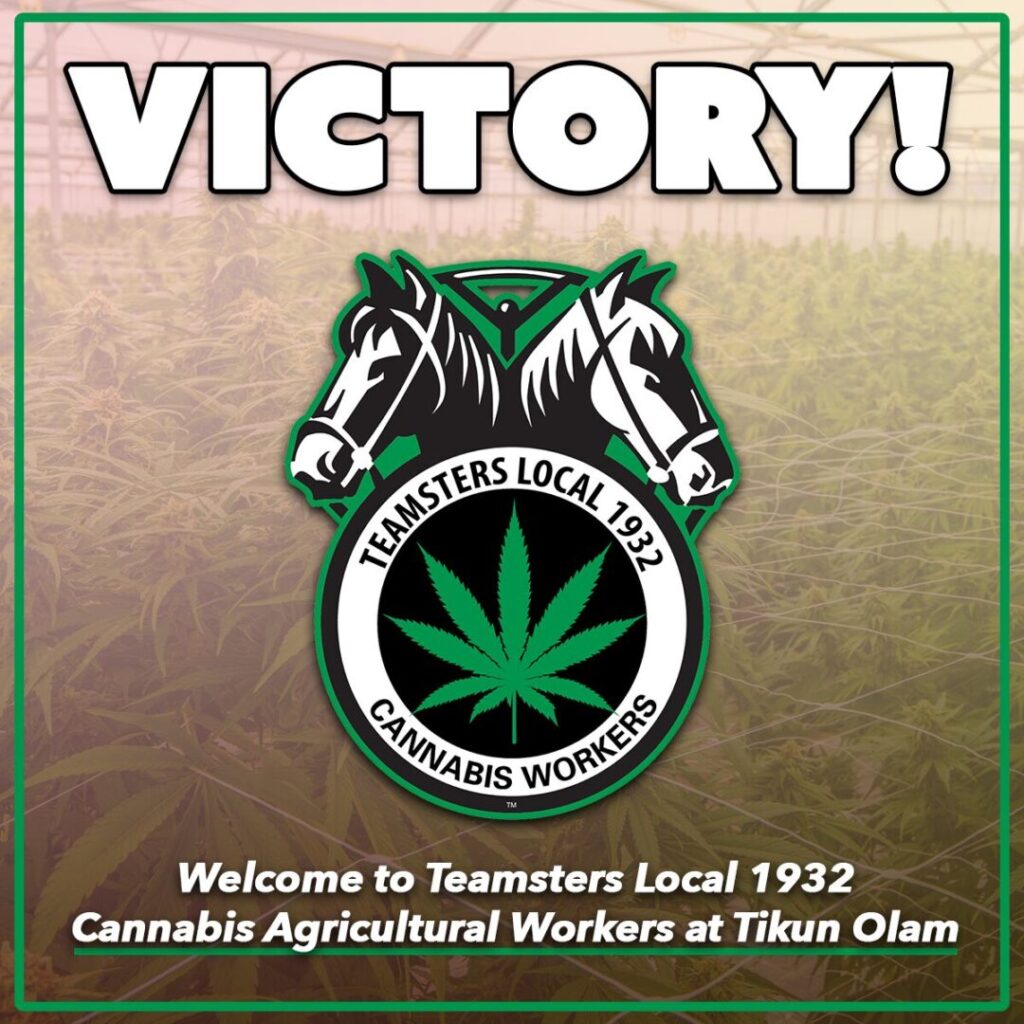

By contrast, the unionization of California cannabis workers is not a pipe dream but a growing reality. Located in California’s Inland Empire, Teamsters 1932 Cannabis Workers Union organizes cannabis agricultural workers, packing facility workers, budtenders, and delivery drivers.46 Local 1932 revises the Teamsters logo of twin horse heads above a wagon wheel by adding a cannabis leaf (Figure 35). Historically, the teamsters have organized truckers and transportation workers, and its recent success unionizing cannabis delivery drivers in pursuit of living wages and safe working conditions recalls the prevalence of cars in cannabis advertising and the desires for freedom they represent. Teamsters similarly articulate gas-powered vehicles to dreams of mobility and transcendence for racialized, low-wage workers.

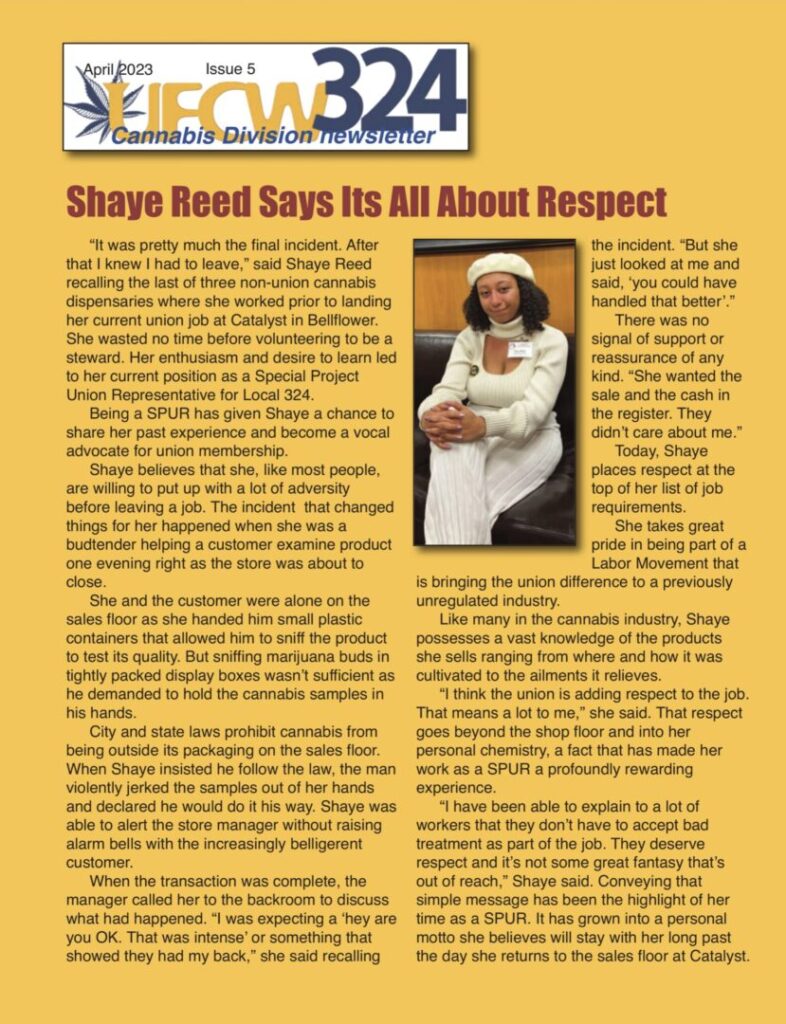

With its “Cannabis Workers Rising” campaign, the United Food and Commercial Workers have organized tens of thousands of workers in dispensaries, labs, delivery services, kitchens, manufacturing, processing, and grow facilities across the United States. The union has won contracts providing job protections, wage increases, holiday pay, retirement benefits, and safer working conditions.47 In California, hundreds of cannabis workers in Orange and Los Angeles Counties have joined the UFCW. The Union’s website page about cannabis features a woman of color worker at the South Coast Safe Access in Santa Ana who is represented by UFCW Local 324. The population of Santa Ana is over 75% Latinx, and so Local 324 is made up of large numbers of Latinx workers, including its cannabis division, and South Coast Safe Access largely serves a working-class Latinx clientele. Indeed, every UFCW Cannabis Newsletter spotlights Black and Latinx women and men who serve as dispensary shop stewards and union organizers (Figures 36–37). Local 324 has also joined the Orange County Labor Federation in hosting clinics to help people expunge records of cannabis crimes as enabled under Proposition 64. As the union website explains, “we see these efforts as an important part of addressing and changing the historical inequities and racism of the War on Drugs.”48 Whereas social equity licenses and DEI marketing do little for cannabis workers, unionization has produced tangible benefits, with wages for union jobs ranging from 10.8–32.4% higher than nonunion jobs in the industry.

Figures 36–37. UFCW 324 Cannabis Division newsletter.

Jose Muñoz suggestively developed his theory of futurity out of an examination of a union. In “The Future Is in the Present: Sexual Avant-Gardes and the Performance of Utopia,” he analyzed performances containing “an anticipatory illumination of a queer world, a sign of an actually existing queer reality, a kernel of political possibility within a stultifying heterosexual present.” Following C.L.R. James he calls such performances “the enactment of . . . a future in the present.” The title of James’s volume, The Future in the Present, according to Muñoz, “riffs on an aspect of Hegelian dialectics suggesting that the affirmation known as the future is contained within its negation, the present.” One of James’s examples is “an actually existing socialist reality in the present”: “In one department of a certain plant in the US there is a worker who is physically incapable of carrying out his duties. But he is a man with a wife and children and his condition is due to the strain of previous work in the plant. The workers have organized their work so that for ten years he has had practically nothing to do.”49 Muñoz draws on James’s account of factory workers as “social performers” in order to “read the world-making potentialities contained in the performances of minoritarian citizen subjects who contest the majoritarian public sphere.”50 The shop floor where workers partly socialize their labor in support of one another resembles the collectivist orientation of cannabis unions. Muñoz’s performance theory thus helps make cannabis unions visible as “anticipatory illuminations” of better worlds, or performances of the future in the present.51

Notes

- See Monte Staton, Brian Kaskie, and Julie Bobitt, “The Changing Cannabis Culture Among Older Americans: High Hopes for Chronic Pain Relief,” Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 29, no. 4 (2022): 382–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2022.2028728. ↩

- I build on the tradition of cultural studies research focused on the contradictions of commodifying racialized popular cultures such as music, food, and fashion. While an exhaustive survey of that extensive body of scholarship is beyond the scope of this essay, here I would emphasize my debt to Stuart Hall’s analysis of how at one and the same time, Black popular culture remains connected to everyday Black lives, desires, and fantasies while being vulnerable to co-optation and commercialization. See Stuart Hall, “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?,” Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, ed. David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen (Routledge, 1996), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203993262. ↩

- Steven W. Bender, “The Colors of Cannabis: Reflections on the Racial Justice Implications of California’s Proposition 64,” UC Davis Law Review Online 11 (2016): 12. ↩

- For the history of cannabis prohibition, see Dominic Corva and Joshua S. Meisel, “Introduction to Post-Prohibition,” in The Routledge Handbook of Post-Prohibition Cannabis Research, ed. Dominic Corva and Joshua Meisel (Routledge, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429320491. See also Curtis Marez, Drug Wars: The Political Economy of Narcotics (University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 105–222. ↩

- Barney Warf, “High Points: An Historical Geography of Cannabis,” Geographical Review 104, no. 4 (2014): 416, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2014.12038.x. ↩

- “Proposition 64: The Adult Use of Marijuana Act,” Judicial Council of California, https://www.courts.ca.gov/prop64.htm. ↩

- Corva and Meisel, “Introduction to Post-Prohibition,” 1–2. ↩

- Kaitlin Reed, “Cannabis, Settler Colonialism, and Tribal Sovereignty in California,” in The Routledge Handbook of Post-Prohibition Cannabis Research, ed. Dominic Corva and Joshua S. Meisel (Routledge, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429320491. ↩

- Bender, “Colors of Cannabis,” 13–14, and 17–18. ↩

- See Beau Kilmer, Jonathan P. Caulkins, Michelle Kilborn, Michelle Priest, and Kristen M. Warren, “Cannabis Legalization and Social Equity: Some Opportunities, Puzzles, and Trade-Offs,” Boston Law Review 101, no. 1003 (2021): 1003–41; Rebecca Brown, “Cannabis Social Equity: An Opportunity for the Revival of Affirmative Action in California,” Social Justice and Equity Law Journal 3, no. 1 (2019): 205–47; and Y. Tony Yang, Carla J. Berg, and Scott Burris, “Cannabis Equity Initiatives: Progress, Problems, and Potentials,” American Journal of Public Health 113, no. 5 (2023): 487–89). ↩

- “Cannabis Equity,” California Department of Cannabis Control, https://cannabis.ca.gov/resources/equity. ↩

- By one estimate the startup cost for a new cannabis dispensary is $240,000. Yang, Berg, and Burris, “Cannabis Equity Initiatives,” 488. ↩

- Yang, Berg, and Burris claim that 80% of cannabis businesses are white owned. Yang, Berg, and Burris, “Cannabis Equity Initiatives,” 487. ↩

- “Ciencia Labs, the Next Generation of Cannabis Brands and IP,” https://ciencialabs.com; “Humo: Where There’s Fuego, There’s Humo,” https://www.gethumo.com; Jessica MacAulay, “Humo’s Susie Plascencia on Cannabis in the Latino Community,” Clio, May 26, 2022, https://musebycl.io/higher-calling/humos-susie-plascencia-cannabis-latino-community; and “Dope Flavors Products: Dr. Che,” https://www.dopeflavorsllc.com/products. ↩

- “Monogram’s De Watson is Repping for the Dignity of Cannabis Culture,” Mary Jane, November 15, 2021, https://merryjane.com/culture/monograms-de-watson-is-repping-for-the-dignity-of-cannabis-culture; and Michelle Lhooq, “Inside Jay-Z’s Weed Lab,” GQ, April 19, 2021, https://www.gq.com/story/jay-z-monogram-cannabis-tour. ↩

- Adam Tschorn, “This Athlete’s Weed Side Hustle Turned into a Movement to Change L.A.’s Cannabis Scene,” Los Angeles Times, September 9, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/lifestyle/story/2021-09-09/how-chris-ball-went-from-professional-football-to-pot-farm. ↩

- “Mission,” Josephine and Billies, https://www.josephineandbillies.com/our-mission/ ↩

- “Queen Latifah Invests in Sixty Four & Hope, Creating Wealth for 21 Entrepreneurs from South LA,” Mary Magazine, December 21, 2021, https://www.mary-magazine.com/business/queen-latifah-invests-in-sixty-four-hope-creating-wealth-for-21-entrepreneurs-from-south-la. ↩

- Quoted by Ayoka Medlock-Nurse, Racial Capitalism and the African American Experience Entering the Cannabis Industry (Walden University, 2021), 124. ↩

- Bootleg Kev, “Berner: Cookies Clothing does 55 Million a Year,” YouTube, September 28, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RuWTlf8M2J4. ↩

- “Social Impact,” Cookies Company, https://impact.cookies.co. ↩

- Berner, quoted by Javier Hasse, “How Berner Built a Half-A-Billion Dollar Cannabis Empire, Forbes, September 16, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/javierhasse/2020/09/16/berner/?sh=660efbb7541d. ↩

- Berner415, “Cookies U,” YouTube, June 17, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DEjZhskYC6E. ↩

- “Cookies U,” Social Impact, https://impact.cookies.co/cookiesu; “Cookies Impact,” Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/cookiesimpact; “Cookies Campus,” Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/cookies_campus; “Cookies Tree Lounge,” https://www.instagram.com/cookiestreelounge. ↩

- “Cookies U,” https://impact.cookies.co/cookiesu. ↩

- Marty Otañez, “A Labor Studies Approach to Cannabis,” in The Routledge Handbook of Post-Prohibition Cannabis Research, ed. Dominic Corva and Joshua S. Meisel (Routledge, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429320491. ↩

- “Cookies Reviews,” Glassdoor, https://www.glassdoor.com/Reviews/Cookies-Reviews-E3117692_P3.htm?filter.iso3Language=eng; and “Cookies Reviews,” Indeed, https://www.indeed.com/cmp/Cookies/reviews. ↩

- Quoted by Hasse, “How Berner Built a Half-A-Billion Dollar Cannabis Empire.” ↩

- Wolfgang Fritz Haug, Critique of Commodity Aesthetics: Appearance, Sexuality and Advertising in Capitalist Society (Polity Press, 1986), 19. ↩

- “Top California Cannabis Distributors: Teds Budz,” LA Weekly, January 14, 2022, https://www.laweekly.com/california-cannabis-distributors/. ↩

- Theo Lewis interview, September 21, 2023. ↩

- Lewis interview. ↩

- Interview with Jacqueline Wallace, September 21, 2023. ↩

- California dispensaries are generally excluded from areas with high home values and tend to be clustered in low-income areas. See Chris Morrison, Paul J. Gruenewald, Bridget Freisthler, William R. Ponicki, and Lillian G. Remer, “The Economic Geography of Medical Cannabis Dispensaries in California,” International Journal of Drug Policy 25, no. 3 (2014): 508–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.12.009. ↩

- Lewis interview. ↩

- Salvador Zárate, “Migrant Labor and a Life Under Fire: A Triptych,” Living Through Upheaval, University of California Humanities Research Institute, June 2022, https://uchri.org/foundry/migrant-labor-and-a-life-under-fire-a-triptych. ↩

- Shana Klein, The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion (University of California Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203421222. ↩

- Cannabis Talk 101, “Theodore Lewis & Anthony Garcia of Teds Budz Distribution Co. | Cannabis Talk 101,” YouTube, October 18, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHscP6T-kac. ↩

- Haug, Critique of Commodity Aesthetics, 20. ↩

- Warf, “High Points,” 426, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2014.12038.x. ↩

- Warf, “High Points,” 428. See also William R. Jankowiak and Daniel Bradburd, Drugs, Labor, and Colonial Expansion (University of Arizona Press, 2003), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2rcnqn9; and Marez, Drug Wars. ↩

- Otañez, “A Labor Studies Approach to Cannabis,” 176. ↩

- Marc B. Schenker and Chelsea E. Langer, “Health and Safety of Cannabis Workers,” in The Routledge Handbook of Post-Prohibition Cannabis Research, ed. Dominic Corva and Joshua S. Meisel (Routledge, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429320491; Stella Beckman, Xóchitl Castañeda, Vania del Rivero, Anaisabel Chavez, and Marc B. Schenker, “Experiences of Structural Violence and Wage Theft Among Immigrant Workers in the California Cannabis Industry,” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 12, no. 3 (2023): 127–40, https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2023.123.014; and Otañez, “A Labor Studies Approach to Cannabis,” 176–77. ↩

- Mary H. Luc, Samantha W. Tsang, Johannes Thrul, Ryan D. Kennedy, and Meghan B. Moran, “Content Analysis of Online Product Descriptions from Cannabis Retailers in Six US States,” International Journal of Drug Policy 75 (2020): 102593, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.10.017. ↩

- Tom Decorte, Regulating Cannabis: A Detailed Scenario for a Nonprofit Cannabis Market (Archway Publishing, 2016). ↩

- “Teamsters 1932 Cannabis Worker’s Union,” https://teamsterscann.org/about. ↩

- “Cannabis Union,” UFCW, https://www.ufcw.org/who-we-represent/cannabis. ↩

- “Community Advocacy,” UFCW 324, https://ufcw324.org/cannabisdivision/communityadvocacy. ↩

- José Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009), 30, https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479868780.001.0001. ↩

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 49. ↩

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 55–56. ↩