This series of photographs tracks digital signals across nine nodes of our fiber-optic undersea cable network—a system responsible for carrying 99% of all transoceanic internet traffic. The images document cable landings in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Tahiti, sites where submarine systems come aground and become entangled in the existing movements of both humans and nonhumans. Rather than locating us in an urban landscape, “Signal Tracks” hones in on the cable system’s rural and aquatic environments, extending from breaking waves over Sydney’s beaches, to mountains where brush fires scour O’ahu’s west shore, to the habitats of endangered mountain beavers in northern California. Although on the surface these images appear absent of industrial infrastructure, the accompanying textual annotations highlight how such “natural” ecologies have been folded into contemporary digital systems.

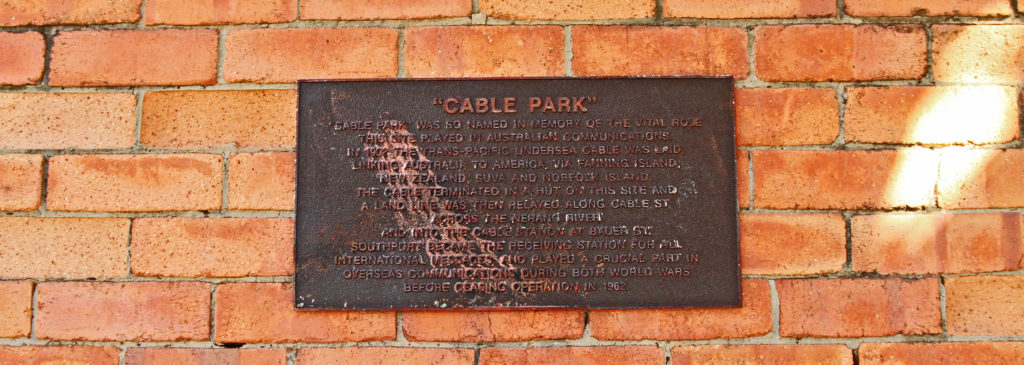

Figure 9. The cable landing at Nelson, New Zealand has been re-purposed as a campground. Inside Cable Bay Holiday Park’s reception area, an amateur archive of collected historical material documents the system’s impact. At the climax of “White Noise,” as the engineers are listening to Moses cross the Red Sea, one of the pair suggests that they should tape and analyze the sounds emanating from the depths. The second engineer resists, arguing that if they continue to listen in and happen to overhear the voice of God, this knowledge would destroy them. “We musn’t hear it,” he exclaims, “We would know for sure. It would make a worthless thing of faith” (Kilworth 514). He pulls the plug, cuts the circuit, and fires a gun at the system. Destroying the cable station, he attempts to preserve a continued faith in the world’s mysteries and a belief in the possibility of earthly transcendence. This short story conveys at least one reality about today’s cable stations: they register traces of the past that are difficult to reconcile with the transcendence networks promise to us. As Anna McCarthy and Nick Couldry have argued, “the full recognition of the materiality of space, and spatial relations, does violence to certain visions, themselves perhaps quite comforting, of what media are” (2004: 3). It is only through the symbolic destruction of this material past that we can continue to believe in the immateriality of our communications networks. Counter to this imagination, the images here suggest that by revisiting and recording the history of cable stations, we might open up a circuit of exchange between today’s systems and the colonial infrastructures that constitute their early foundations.

Works Cited

Couldry, Nick and Anna McCarthy, eds. MediaSpace: Place, Scale and Culture in a Media Age. London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

Graham, Stephen and Simon Marvin. Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition. London: Routledge, 2001.

Kilworth, Gary. “White Noise.” In Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror Volume 3, Ellen Datlow, ed.. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1990. pp. 508-16.

Scott, R. Bruce. Gentlemen on Imperial Service: A Story of the Trans-Pacific Telecommunications Cable told in their own Words by those who Served. Victoria: British Columbia, 1994.