From at least the beginnings of the eighteenth-century abolition movement, black people in Britain urged political change locally, throughout the empire, and in the United States—a presence and intellectual contribution that is too often overlooked by historians of the British left. This public critique, pronounced from speaking podiums and in newspapers, identified intersecting oppressions of racism, sexism, and colonialism that manifested on a local and global scale. Jamaican poet Claude McKay arrived in London after the end of World War I, just a few years after the Russian Revolution, a time of political flux and fears. In the face of violent attacks on people of color—black soldiers returning to American cities, and workers arriving from the colonies to British docks—McKay staked a claim for the full humanity of black people in the pages of a weekly newspaper edited by the radical Sylvia Pankhurst. McKay’s writings, facilitated by Pankhurst’s institutional interventions, pushed against dangerous race-baiting of the self-identified British left and articulated an alternate political stance. In The Workers’ Dreadnought, McKay explained the promise of nationalism for mobilizing colonized people; he discussed the symbolic role of white womanhood in perpetuating racism against blacks; and he called out the hypocrisy of white hysteria around the presence of African troops in Germany. He adamantly rejected the widely-circulating logic that color or national origin determined sexual aggression and violence, and drew attention to sexual violence against black women by colonial forces in the Caribbean. McKay articulated a set of political positions in the pages of the Dreadnought which he continued and transmuted in speeches and fiction throughout the decade. McKay’s protest in the pages of Pankhurst’s newspaper places him in a longer history of black British political engagement, denying the racist criminalization of blackness, staking a claim for the humanity of Caribbean and African migrants, and speaking back through the press to challenge and shape public opinion especially amongst the British left.

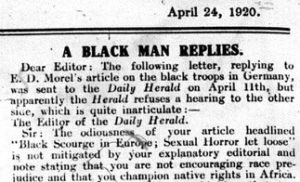

On April 24, 1920, Jamaican poet Claude McKay published a letter to the editor in Sylvia Pankhurst’s London-based newspaper, The Workers’ Dreadnought. The letter addressed the editor of a different paper, however, which McKay discussed in an accompanying note: “Dear Editor: The following letter, replying to E.D. Morel’s article on the black troops in Germany, was sent to the Daily Herald on April 11th, but apparently the Herald refuses a hearing to the other side, which is quite inarticulate.”1 The Daily Herald, edited by George Lansbury, had published an article by Edward Morel, “Black Scourge in Europe: Sexual Horror Let Loose by France on the Rhine.”2 As the headline suggests, Morel’s sensationalist article raises the alarm that French colonial troops from Africa, stationed in Germany after World War I, present a sexual threat for European womanhood. McKay, a Jamaican writer who had recently moved to London after living in the US, wrote against Morel’s racist claims about black sexuality without adhering to conservative mores or denying his sexuality. He wrote, “I, a full-blooded Negro, can control my sexual proclivities when I care to, and I am endowed with my full share of the primitive passion.” He continued, “Besides, I know hundreds of negroes of the Americas and Africa who can do likewise.” In the pages of The Workers’ Dreadnought, McKay challenged the Herald, and, more broadly, the culture of the British Left, to reject its beliefs about the “primitive” Africans.

“Why all this obscene, maniacal outburst about the sex vitality of black men in a proletarian paper?” McKay asks of the Herald. McKay calls out the hypocrisy of the socialist paper and suggests that even liberal and conservative papers are more responsible in reporting colonial conflicts. “If you are really consistent in thinking that you can do something to help the white and black peoples to a better understanding of each other, there is much you might learn from Liberal and Conservative organs like The Nation, The New Statesman and the Edinburgh Review,” McKay chides. As Robert Reinders remarked, “If this article had been written by an American racialist and had appeared in a Klan journal it might have little intrinsic historic interest. But the Herald was the leading left-wing daily in Britain, ‘at the height of its power’; and the editor, George Lansbury, was a figure of national importance.”3 Morel’s protected status in Lansbury’s publication, shielded from McKay’s criticism, suggests that the mainstream British Left was uninterested in making space for black men. Instead, McKay found a place in a different proletarian paper to publish his reply to Morel’s vitriol. In fact, according to Barbara Winslow, The Workers’ Dreadnought was “the only British socialist newspaper that had black correspondents.”4 McKay’s publication in Sylvia Pankhurst’s East London newspaper highlights the importance and singularity of the space she created on the British left for publishing dissenting opinions.

The arrival of the SS Empire Windrush to London in 1948 tends to be held as the beginning marker of black Britain, when Caribbean postwar migration began en masse and significantly changed the racial makeup of the small island nation. However, black intellectuals were participating in and protesting British culture for decades before the Windrush arrived. This expanded view of black British history is apparent in books like Black Edwardians, Black Victorians/Black Victoriana, From Scottsboro to Munich: Race and Political Culture in 1930s Britain, and others.5 McKay’s moment at Pankhurst’s newspaper comprises a lesser-known intervention in black British literature and culture. McKay used the platform of Pankhurst’s leftist weekly newspaper to argue against racist beliefs about black sexuality and the mythology of white womanhood. McKay’s intervention takes part in a long tradition of black writers in Britain protesting the criminalization of blackness. (Pankhurst also finds a place in a wider history of British antiracism, as a white woman committed to fighting racism and imperialism with access to a printing press.6)

Lansbury was an established, esteemed member of the British Left and Pankhurst was no stranger to demanding the British Left be more accountable—to women, to revolutionary, anti-Parliamentarian politics, and to people of color. This led to Pankhurst and Lansbury’s complicated working relationship—though Lansbury supplied the Dreadnought with funds for things like paper, Pankhurst did not shy from disagreeing with him publicly. While there were times she apparently suppressed some criticism of Lansbury, in this case, she promoted McKay’s protest, published under the headline “A Black Man Replies.”7

Sylvia Pankhurst had already been writing against race prejudice prior to McKay’s arrival in the pages of The Workers’ Dreadnought. She responded to attacks on black and brown sailors that arrived at the docks nearby the paper’s East London offices. In 1919, in East London as well as in other port cities in England, the Caribbean, and across the United States, race riots erupted as white people attacked men of color arriving as workers or as veterans after the first World War.8 Just as Morel believed the Senegalese soldiers in Germany would ruin European women, white British residents in the dock areas were motivated by beliefs in the sexual threat black men posed for white women. In Pankhurst’s East London neighborhood, there were multiple racially motivated attacks against men of color who arrived on the docks. One Dreadnought article from June 1919, “Stabbing Negroes in the London Dock Area,” countered that sailors of color were victims of colonialism and capitalism, exploited to fight wars and work on behalf of white capitalists.9 Therefore, the Dreadnought argued, white working class men should forge solidarity with, rather than violently attack, the sailors. Pankhurst’s paper puts forth an editorial position that consistently argues for the inclusion of people of color in the category of worker, oppressed by colonial and capitalist systems.

Circuits of transatlantic radical publications brought McKay into the orbit of Pankhurst’s newspaper. Pankhurst published McKay’s poem “If We Must Die,” on September 6th, 1919 before McKay even arrived in England. The poem, which is almost certainly his most famous poem, is a response to the race riots which set off as black soldiers returned to US cities. The introduction in the Dreadnought declared, “We take from the NY Liberator . . . these poems by Claude McKay.”10 The headline advertised the author’s race: “A Negro Poet.” McKay’s poem must have resonated with Pankhurst’s local experience of the race riots in East London. When East London and Chicago erupted in race riots, McKay and Pankhurst each took a public stand against the racist violence.

McKay lived in England from 1919 to 1920. McKay had grown up in Jamaica, and spent several years in the United States, most recently in New York, where he worked at Max and Crystal Eastman’s radical newspaper The Liberator. The Grays, American siblings with aspirations of founding a utopian society, sponsored his trip from New York to England.11 Arriving with letters of introduction for George Bernard Shaw and C.K. Ogden, and joining the communities of the International Club and a club for colored soldiers, McKay entered London’s literary, socialist, and diasporic worlds.12

McKay had grown up in Jamaica at a time when British reformers and socialists were taking refuge there.13 Walter Jekyll, a white British transplant to Jamaica, mentored him and encouraged him to write poetry that incorporated Jamaican dialect, which McKay did in his first book of poems, Songs of Jamaica.14 McKay also met Sydney Olivier, the socialist Jamaican governor at the turn of the twentieth century, through Jekyll.15 These older British men, involved with socialism and reform movements in England, were of the same generation and intellectual community as Pankhurst’s parents, who were involved in socialist politics in Manchester during her youth. McKay and Pankhurst shared an intellectual background, not only through imperial literature and history curricula, but also in their political influences. Joshua Gosciak’s work on McKay’s queer and political relationships with these British men in Jamaica and England suggests an important intellectual through-line that also connects McKay and Pankhurst, and the British suffrage and socialist politics for which she stood.16 Pankhurst and McKay were similarly influenced by nineteenth century reform movements that aimed to transform language, aesthetics, and the world.

Pankhurst had grown up in the socialist politics of Manchester, and moved to London as an art student, where she joined her mother Emmeline and sister Christabel and their militant organization the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).17 At the outset of World War I Sylvia Pankhurst split from the WSPU, when the organization aligned itself with the state’s war efforts in a bargain to get women the vote. Pankhurst, opposed to the war, and increasingly interested in class issues, founded the East London Federation for Suffragettes (ELFS). The ELFS founded the Woman’s Dreadnought, a weekly newspaper whose name invoked the type of war ship. Within a few years, the group transformed to be the Workers’ Suffrage Federation, in 1916, and after the Russian Revolution, in 1918, to the Workers’ Socialist Federation. The title of the newspaper changed as well, to the Workers’ Dreadnought, a newspaper that published international news from a revolutionary, far-left editorial standpoint. East London, where Pankhurst had lived for six years by 1920, was a diverse, working-class area, full of immigrants, with large Jewish, Irish, and Chinese populations.18 Its docks brought sailors from around the world, including the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Pankhurst’s paper embraced its location in the East End, imagining the area’s socialist future. One 1919 article on peace parties in the town of Bow reported, “The people in the poor, little streets of Bow have begun by organising children’s parties: some day they will organise the Soviets.”19

Pankhurst was an outspoken figure on and fearless critic of the British left. During the year McKay was at the Dreadnought, Pankhurst would break with Lenin and the Communist International over whether British communism should engage in parliamentarian politics. Lenin, and the newly endorsed British Communist Party, believed they should engage with Parliament. Pankhurst did not, falling further to the Left on this question. She traveled to the Soviet Union and lobbied that the position of the official British representatives to the congress should not be adopted as the Communist line.20 After her return, she exchanged letters with Lenin, which she published in her newspaper, arguing over the place of Parliamentary engagement in communist politics. Ironic, as Morag Schiach points out, that someone who worked so hard toward gaining the vote for women and working men would turn entirely away from parliamentary politics.21 Pankhurst was thrown out of the party, and her newspaper, which had been an official organ of communism in Britain, lost that distinction. Even in the memoir A Long Way from Home, in which he distanced himself from so much of his socialist and political activities of the 1920s, McKay vouched for Pankhurst’s commitment to anticolonial causes. He recalled, “she was always jabbing her hat pin into the hinds of the smug and slack labor leaders. Her weekly might have been called the Dread Wasp. And wherever imperialism got drunk and went wild among native peoples, the Pankhurst paper would be on the job.”22 Even in retrospect, at a cynical distance, McKay cannot dismiss Pankhurst’s energetic commitment to anti-colonial, activist, outsider journalism.

In his articles for the Dreadnought, McKay lays out a political project that he grappled with throughout the decade. Ideas he published in the Dreadnought resurfaced in his 1922 comments to the fourth congress of the Third Communist International, and in his fictional representations of black diasporic politics in the 1928 novel Banjo.23 In his first article for the Dreadnought, “Socialism and the Negro,” published in January 1920, McKay, a Jamaican in the metropole, a product of the empire, argues to the British Left that they ought to align themselves with anticolonial movements, just as he would again in April, in his letter to the editor. In “Socialism and the Negro,” he argues that British socialists should support anti-colonial nationalist movements.24 Noting his own interest in the Garvey movement, he wrote, “for subject peoples, at least, Nationalism is the open door to Communism.” He proposes anti-colonialism, including anti-colonial nationalism, as a most important socialist effort, and criticizes the blindness of white British socialists to this strategy, commenting:

Some English Communists have remarked to me that they have no real sympathy for the Irish and Indian movement because it is nationalistic. But, to-day, the British Empire is the greatest obstacle to International Socialism, and any of its subjugated parts succeeding in breaking away from it would be helping the cause of World Communism.25

Famously, McKay makes a very similar argument a couple of years later during the Communist International’s congress in the Soviet Union. In 1922, his foundational speech “On the Negro Question” resulted in the Communist International’s Black Nation Thesis, and a series of actions in the US South (where the Black Belt, and the site of this “nation within a nation” was to be located) through the first half of the 1930s.26 The Communist International adopted the strategy of minority nationalism to foster communism. In his 1920 article, as in his 1922 speech, McKay identifies the US South as a potential site to target for organizing.

The Dreadnought had an international range and had published reports from the Easter Rising in 1916 Dublin, as well as other accounts of anti-colonial sentiment from Ireland, India, and beyond. Indeed, an article on agricultural workers in Argentina followed McKay’s “Socialism and the Negro.” In the same issue, two of McKay’s poems appeared on a page of the Dreadnought following the article “The Colour Bar: A Cry from South Africa.” Pankhurst’s newspaper was also exceptional among left British publications for its inclusion of black writers and attention to African and African-diasporic viewpoints. So, when April arrived, and the Daily Herald published Morel’s “Black Scourge in Europe,” the Dreadnought was a natural venue for McKay’s response, especially after Lansbury had refused to publish it. McKay already had a relationship with the Dreadnought, and had already challenged the British Left to be more accountable to colonial subjects in its pages.

McKay recalls in his 1937 memoir A Long Way from Home that he began writing for the Workers’ Dreadnought after the publication of his letter to the editor of the Daily Herald—which turns out to be a misremembering, but a suggestive misremembering. In fact, McKay had been writing for the Workers’ Dreadnought for several months prior to the letter’s publication in April 1920. As Wayne Cooper and Robert Reinders report in their article on McKay’s time in London, “A Black Briton Returns,” “McKay’s account may be somewhat awry.”27 His 1937 version of the story suggests the power of the letter to the editor as a form of entry. Awry though the account may be, the version in the memoir suggests that the letter to the editor comprises a striking gesture—an interruption, a turning point—and a compelling narrative of arrival.

A letter to the editor is a public intervention. It allows readers to enter the pages of the newspaper, voice their views, and join a conversation. The letter to the editor section affords an opportunity for readers to appear in print—a distinctly modern media phenomenon, as printing technologies became less expensive, and more common. Walter Benjamin identified this moment as comprising a fundamental shift in the relationship of reader and writer—“it began with the space set aside for ‘letters to the editor’ in the daily press,” he writes, until any European could find somewhere to print their thoughts.28 “Thus,” Benjamin concludes, “the distinction between author and public is about to lose its axiomatic character.” This example of a black Briton writing back to the white British mainstream left offers an important addendum to Benjamin’s observation. (Today, the use of social media to challenge and influence mainstream news cycles offers a parallel change—a forum like Twitter offers amplification of more diverse voices with the loss of the ‘axiomatic character’ of twentieth-century journalism.) With the explosion of print in the twentieth-century, those people historically excluded from the world of letters—women, colonial subjects, black and brown people—increasingly find space to dissent.

The letter to the editor also does work for the paper in which it appears, of course. At a later moment of racialized moral panic in Britain, the authors of Policing the Crisis analyzed letters to the editor about the 1972 Handsworth mugging case.29 The authors of the chapter argue that the “principal function” of letters to the editors “is to help the press organize and orchestrate the debate about public questions.”30 McKay’s thwarted attempt to print his letter in the Herald demonstrates this selection on the part of the Herald. As the authors of Policing the Crisis note, letters to the editor “are not an unstructured exchange but a highly structured one.”31 The Dreadnought constructed its own community of news sources and subscribers, hailed especially in the ads and letters of its pages. Occasionally, the news stories themselves would also invoke the networks of activists, where Pankhurst played a prominent role, placing the readers in a direct line to German Communist and founder of International Women’s Day, Clara Zetkin, or Lenin, or the Finnish Communist Party, for instance. In others, the pages appealed to readers to subscribe, to share their papers and encourage others to read, to hang posters in news agencies. Directly below McKay’s letter to the editor, a notice announces “In order to save expense to Comrades, both in town and country, who cannot obtain the Dreadnought from a neighbouring newsagent, we have decided to reduce the rates for future subscriptions.”32 Just as Benedict Anderson identified newspapers as crucial technology to create imagined community, we can see how the Dreadnought conjured its community of readers “in town and country.”33 And that community of readers was familiar with columns that challenged mainstream socialism.

Though overwhelmingly the paper covered the presence of African troops according to white supremacist beliefs, the Daily Herald did publish an exchange of letters to the editor between Morel and a man who protested Morel’s claims. The letter of protest was lodged by Norman Leys, who explains he’s lived “for 17 years in tropical Africa, for the last three of them in company with black troops.”34 Leys protests Morel’s claims about African sexuality: “it is untrue that sexual passion is stronger in Africans than in Europeans. And it is untrue that sexual connection between an African male and European female is injurious to a European female.” Leys argues that the belief that sexual passion is stronger in Africans is “one of the great sources of race hatred” and “should never be repeated by any honest man or honest newspaper.”35 Morel writes to respond a few days later, dimissing Leys’ charge, stating that the question of “whether sexual passion is stronger in the African” is one “upon which it is possible to hold different views without flinging about charges of dishonesty.” He concludes by flaunting his credentials, among “those who have been defending the African peoples against race exploitation and race prejudice for more years than Dr. Leyds [sic] has spent in East Africa.”36

McKay’s letter to the editor was printed for the readers of the Dreadnought but made its appeal much more widely. He calls for British socialists to be more accountable to victims of empire. In his complaint to the Daily Herald, McKay questions the political commitments of a socialist paper that circulates such racist vitriol. He argues:

The stopping of French exploitation and use of the North African conscripts (not mercenaries, as your well-informed correspondent insists they are) against the Germans is clearly a matter upon which the French Socialists should take united action. But not as you have done.37

McKay agrees that the presence of these colonial conscripts is a problem—but not for the reasons Morel puts forth. This argument resonates with a moment in McKay’s novel Banjo, published at the end of the decade, in 1928. The protagonist, Ray, an African American living in Marseille, had saved a clipping of a letter to the editor. The letter argued that a Senegalese soldier who had committed murder had done so because he had been taken out of his native land: “Transplanté, déraciné, il est devenue un fou sanguinaire” (transplanted, deracinated, he became a bloodthirsty madman). The novel reflects, “it was such an amusing revelation of civilized logic that Ray had preserved it, especially as he was in tacit agreement with the thesis while loathing the manner of its presentation.”38

Similarly, in McKay’s remarks in the Dreadnought, he implicitly agrees that the presence of colonial conscripts is a problem, but totally objects to the reasoning of Morel’s argument. At another point in the novel, Ray recalls that he was in Germany when the French had black troops stationed there:

A big campaign of propaganda was on against them, backed by German-Americans, negro-breaking Southerners, and your English liberals and socialists. The odd thing about that propaganda was that it said nothing about the exploitation of primitive and ignorant black conscripts to do the dirty work of one victorious civilization over another, but it was all about the sexuality of Negroes—that strange, big bug forever buzzing in the imagination of white people.39

This remark, like the letter to the editor Ray carries with him, resonates with the opinions McKay put forth earlier in the decade in his own letter to the editor. McKay addressed those “English liberals and socialists” directly in the pages of the Dreadnought. While many of McKay’s political stances shifted during the 1920s, in Banjo, Ray faithfully echoes McKay’s own position from his time in England.

McKay reproached the Daily Herald for goading racist violence. He reports he’s been “told in Limehouse,” an East London neighborhood, “by white men, who ought to know, that this summer will see a recrudescence of the outbreaks that occurred last year”—more attacks on people of color on the docks.40 McKay again points out the hypocrisy of the Herald‘s position: “The negro-baiting Bourbons of the United States will thank you, and the proletarian underworld of London will certainly gloat over the scoop of the Christian-Socialist-pacifist Daily Herald.”

In the United States, the mythology of white womanhood, and the complicity, participation, and endorsement of white women, underwrote the terror of lynching. In Europe, the same logic was applied to condemn the presence of Senegalese soldiers in the Rhine Valley, and to attack the black and Asian sailors and workers arriving at the docks. In this worldview, white women are sexually pure, without sexual agency, and the protectors of whiteness. As Vron Ware points out in Beyond the Pale, this logic took on special valences in the British colonial context. Ware notes that “English women were seen as the ‘conduits of the essence of the race’” who “symbolized not only the guardians of the race in their reproductive capacity, but they also provided […] a guarantee that British morals and principles were adhered to in the settler community,” citing examples in India, Nigeria, and South Africa.41 Ware notes that “the degree to which white women were protected from the fear of sexual assault was a good indication of the level of security felt by the colonial authorities.”42 Clearly, this logic of fear, protection of white women, and subordination of colonized people that informed colonial policy in the Victorian era also ruled the response to the presence of Senegalese troops in Europe in this moment of insecurity after World War I, which had resulted in the loss of life of so many soldiers, and the increased mobility and visibility of soldiers of color in Europe. Like colonial officers abroad, English culture at home rallied around the purity of white women under threat from black men, in a moment of crisis.

Notably, the white women held up in 1920 were working class, impoverished, and often prostitutes. This embrace of the white womanhood of prostitutes comprises a departure from Victorian definitions of whiteness, in which working class women were less white than middle and upper class women who remained in the private realm. Radhika Mohanram explores the ways gender, race, and class came to define whiteness in the Victorian age, particularly noting the Contagious Disease Act of the 1860s, which imprisoned white prostitutes who had contracted venereal diseases, the incidence of which increased significantly when troops returned from India after the Sepoy Rebellion.43 Mohanram concludes, “whiteness was not just about racial differences, but also about the covering over of class differences in the threat of black violence”—an observation that applies even more so to this moment in 1920, when the class and occupation of the women is much less a concern than their race.44

McKay calls out imperial constructions of white womanhood and black sexual aggression, inserting himself into a long history of such protest. Ida B. Wells got run out of the US South at the end of the nineteenth-century when she argued that white women could be engaged in consensual sexual relationships with black men.45 McKay makes a related argument, introducing the possibility that black men have control over their sexual behavior, and are not exceptionally prone to violence or disease. Not only can white women choose and consent to have sex with a black man, but a black man can choose appropriate sexual encounters. Morel spread his message that “you cannot quarter these men upon a European countryside, without their women folk, without subjecting thousands of European women to willing, or unwilling, sexual intercourse with them,” but Pankhurst and McKay refused the rhetoric.46 Revealingly—”willing, or unwilling”—any kind of sexual act between a white woman and black man is equally chilling to Morel. McKay challenged this in an even more straightforward statement in 1922. He wrote in Negroes in America that women have a “duty […] to overturn the malicious assertion that their relations with colored comrades must necessarily be immoral and to show that this is a vile lie and slander.”47

When the Daily Herald published Morel’s article, they called on women to act, but not in the way McKay urges. The Herald ran an announcement stating “We hope all our readers, but especially our women readers, will give close attention to the article by E.D. Morel which we print to-day on another page.”48 Morel’s argument pivoted on white womanhood under siege, and he courted the support of white women’s organizations. One section of his article was titled “Outrage on Womanhood,” in which he spells out the links between women as bearers of whiteness and empire: “The French militarists are perpetrating an abominable outrage upon womanhood, upon the white race, and upon civilization.”49 In Morel’s letter to the editor of April 21, he urges that European women should organize to protest the presence of black troops. Morel argues in his letter that “to drag tens of thousands of primitive Africans, among whom the sexual impulse is of necessity strongly developed, from their homes in West Africa, and to quarter them, without their women folk […] to do this is to subject thousands of white women to sexual intercourse with these men.” Morel states this is “a monstrous outrage upon both races against which the women of Europe should protest on behalf of European womanhood.” And, indeed, women did take up this charge.

A few days after Morel’s article, the Daily Herald reported on the several resolutions passed by organizations to protect white women, under the title “Black Troops Terror.”50 The Central Committee of the Women’s Co-operative Guild had passed a resolution urging the British government to influence France to withdraw the Senegalese troops. The Hereford and District Trades and Labour Council lodged their protest “on the ground of morality, the safe-guarding of white women, and the purity of Europeans from the black strain.” In Wales, the Merthyr Independent Labour Party and Merthyr Peace Council planned a national campaign, the Herald reports, in response to Morel’s article. Morel’s widely reprinted pamphlet Horror on the Rhine included an endorsement by Frau Rohl, Socialist Minister of the Reichstag: “We appeal to the women of the world to support us in our protest against the utterly unnatural occupation by coloured troops of German districts along the Rhine.”51 After hearing Morel speak, the Women’s International League passed a resolution affirming, “in the interests of good feeling between all the races of the world and the security of all women to prohibit the importation into Europe for warlike purposes of troops belonging to primitive peoples.”52 White women in Europe became political agents in response to this perceived threat.

This mobilization of women’s groups stands in contrast to what took place at the Dreadnought. Sylvia Pankhurst’s anti-racist feminist project and McKay’s conception of white women’s potential role in fighting racism, articulated in an earlier article for the Dreadnought, refuses the foundational belief that white women need to be protected from black men. Pankhurst was not invested in holding up the mythology of white womanhood, with its valences of sexual purity and powerlessness. Like McKay, who had relationships with men, she didn’t subscribe to the sexual mores of her time, and would a few years later proudly have a child with Italian anarchist Silvio Corio without being married. The 1919 Dreadnought article “Stabbing Negroes in the London Dock Area” took aim at paranoia around white women’s sexuality:

Are you afraid that a white woman would prefer a black man to you if you met her on equal terms with him? Do you not think you would be better employed in getting conditions made right for yourself and your fellow workers than in stabbing a black man who would probably prefer to bring a black wife over with him if he could afford to do so; and would probably have stayed in Africa if the capitalists had left him and his country alone?53

The line of argument is not as affirming as McKay’s defense of black agency, as it relies on floating the less threatening possibility—probability—that black men would not be interested in white women or being in Europe. Nonetheless, the argument dismisses white women as a pinnacle or ideal, and mocks white anxieties around interracial relations. Pankhurst dispenses with what Hazel Carby later termed “white women […] as the prize objects of the western world.”54

Black women are absent from much of the debate around the presence of African troops in Germany. The alarmist faction that believed the African troops posed a violent, sexual threat occasionally invoked the absence of “their women folk” as reason that the “primitive Africans” were preying on white women.55 In general, the moral panic around African men in Europe neglected to consider black women as agents; rather, they were spectral figures, whose absence enabled the “sexual horror.” The role of black women in this account is entirely passive, simply a population far removed that serves to absorb the sexual activity of black men. As Carby argued in “White Woman Listen!” later in the twentieth century, white feminism failed to account for the experiences of black and brown women under racism and imperialism.56 In contrast, in his letter, McKay highlighted colonial histories in which white soldiers in the West Indies raped black women.

McKay invoked European colonial history to challenge assumptions about the moral superiority of white civilization. In fact, in his letter to the editor, McKay dismisses the premise that an entire race could be deemed “degenerate.” McKay takes aim at the logic of white supremacy, writing, rather provocatively, “During my stay in Europe, I have come in contact with many weak and lascivious persons of both sexes, but I do not argue from my experience that the English race is degenerate.” His comments incorporate rhetoric of disease and dirtiness (“I have known some of the finest and cleanest types of men and women among the Anglo-Saxon”), while dispensing with the racialization of these categories. He also rebukes Morel’s accusation that the soldiers are spreading syphilis with a counterargument he ascribes to competent medical experts: “where [syphilis] is known among blacks it has been carried thither by the whites.”

McKay had earlier considered how to use the logic of white superiority against itself. In his earlier article “Socialism and the Negro,” McKay argued that white women might be uniquely positioned to fight black oppression because of their special status under white supremacy. In a move that follows Ida B. Wells and anticipates Hazel Carby, McKay identifies the centrality of the myth of white womanhood in anti-black racism. McKay suggests that those opposed to black oppression should manipulate the valorization of white womanhood by sending white women to organize in the U.S. South:

Coloured men from the North cannot be sent into the South for propaganda purposes, for they will be lynched. White men from the North will be beaten and, if they don’t leave, they will also be lynched. A like fate awaits coloured women. But the South is boastful of its spirit of chivalry. It believes that it is the divinely-appointed guardian of sacred white womanhood, and it professes to disfranchise, outrage and lynch Negro men and women solely for the protection of white women.

It seems then that the only solution to the problem is to get white women to carry the message of socialism to both white and black workers.57

McKay argues that white women can have a particular role in challenging Southern racism. He proposes women as political agents, and, like the militant suffrage movement that Pankhurst took part in, conceives of ways that patriarchal expectations for lovely and refined white women can be used for political gain. He makes this claim while working at a socialist newspaper run by a white woman in East London. Pankhurst’s presence in East London, as editor of a radical newspaper that opposed racism and exploitation, suggests a historical role of white women, other than as symbols of or defenders of white womanhood.

McKay publishing to protest the mythology of white womanhood in Pankhurst’s newspaper has significant historical precursors. The pages of woman-edited British newspapers had previously published similar protests from black writers from the Americas. For instance, Catherine Impey’s Anti-Caste received support from Frederick Douglass, who in 1888 sent five dollars in support of her work and told her, “I think, however, that you are more needed in America than in England.”58 The publication declared that Anti-Caste “claims for the darker members of the Human Family everywhere a full and equal share of Protection, Freedom, Equality of Opportunity, and Human Fellowship.”59 When Ida B. Wells came to England, her speaking tour was promoted and documented in the pages of Anti-Caste, and Fraternity, a publication that split from Anti-Caste edited by Celestine Edwards. They published Well’s anti-lynching pamphlet “American Atrocities.” An August 1894 article from Fraternity reported, “if the women of the South were all ‘pure in heart and sound in head’ we should hear of fewer lynchings.”60 These publications, with links to the Quakers and the British abolitionist movement, organized women to advocate on behalf of racial justice, at the same time that Wells pushed them to acknowledge and address the role of white women in perpetuating racial inequality.61

McKay’s time at the Dreadnought came to an abrupt end in October 1920, when Pankhurst was arrested, tried, and served a sentence at Holloway Prison for violating the Defence of Realm Act. The Dreadnought had published “Discontent on the Lower Deck,” an article written by an anonymous British sailor, identified as S. 000 (Gunner), H.M.S. Hunter, that expressed his frustration with the navy. The sailor was a devoted reader of the paper, and McKay had previously arranged copies for distribution on the sailor’s ship.62 In “Discontent on the Lower Deck,” the sailor advocated a class-based, anti-war stance: “Stand by your class. Men of the lower deck: Are you going to see your class go under in the fight with the capitalist brutes who made millions out of your sacrifices during the war?”63 Soon after the article was published, the London police raided the Dreadnought’s office, and prosecuted Pankhurst under the Defence of Realm Act.

McKay narrates the police raid in A Long Way from Home. As the office was raided, he smuggled a draft of the incriminating article out of the office, and flushed it down the toilet. (I have always read this reported act in tandem with the drafts of poems Pankhurst wrote on toilet paper while she was imprisoned, which now have a home in an acid free archival box in the British Museum, as examples of diverging fates of the material culture of activism and protest.) McKay, according to his account in the memoir, eluded the attention of the police by playing against their prejudice:

“And what are you?” the detective asked.

“Nothing, Sir,” I said, with a big black grin. Chuckling, he let me pass. (I learned afterward that he was the ace of Scotland Yard.) I walked out of that building and into another, and entering a water closet I tore up the original article, dropped it in, and pulled the chain.64

McKay strategically effaces his selfhood in the moment, in order to escape scrutiny from the police, dispose of the incriminating article, and save the author from punishment. However, McKay was even more central than he let on in his memoir. A report from November 6, 1920 recorded the charges:

The formal charge against Miss Pankhurst was that she did an act calculated and likely to cause sedition amongst His Majesty’s Forces, in the Navy, and among the civilian population, by publishing and causing and procuring to be published in the City of London, a newspaper called the Workers’ Dreadnought, organ of the Communist Party, dated October 16th, 1920, containing articles called “Discontent on the Lower Deck,” “How to get a Labour Government,” “The Datum Line,” and “The Yellow Peril and the Dockers,” contrary to Regulation 42 of the Defence of the Realm Regulations.65

“The Yellow Peril and the Dockers” was written by Leon Lopes. McKay’s biographer Wayne Cooper notes “Leon Lopes” was very likely one of McKay’s pseudonyms.66 “Yellow Peril,” like McKay’s letter to the editor, objects to white men’s physical and verbal attacks on workers of color for their sexual relationships with white women. Like McKay’s letter to the editor and previous coverage of racial attacks perpetrated by white dockworkers, “Yellow Peril” urged white working people to see a common cause with “aliens,” “Jews,” and “Asiatic” workers: “The dockers, instead of being unduly concerned about the presence of their coloured fellow men, who, like themselves, are the victims of Capitalism and Civilization, should turn their attention to the huge stores of wealth along the water front.”67 As Barbara Winslow’s article on Pankhurst suggests, Pankhurst’s testimony during the trial strongly suggests McKay was the author: “Leon Lopez, being a coloured man—who is not a British subject perhaps—felt this keenly, and he put his letter in this paper; and I, as editor, felt he had a right to put it there and point out to the workers that unemployment is caused by deeper things than this.”68

In her testimony at the appeal, Pankhurst argued that “Yellow Peril on the Docks” and “Discontent on the Lower Decks” were not advocating looting or senseless violence, but rather were part of a scientific, rational attempt to transform society.69 Pankhurst cited what she called “standard books” that advocated a message similar to the allegedly incriminating articles, in order to show that if such books were collected in libraries without controversy and were not the object of criminal investigations then neither should her paper be. She juxtaposes her discussion of these Dreadnought articles with writing by William Morris, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and other authors and thinkers who methodically challenged the present society. Pankhurst’s approach was not legally sophisticated (as she and others noted during her own defense), but it was literary. She compiled quotations from other articles in the paper and other books in conventional libraries to show the ideas her newspaper put forth were accepted in other contexts. The newspaper posed a more urgent threat, apparently, in the eyes of the law.

The paper continued to publish during Pankhurst’s imprisonment, and for several years afterward. The Dreadnought published the full text of Pankhurst’s appeal in a special issue, and after the issue sold out, in pamphlet form. After Pankhurst was released, she turned her attentions to publishing a literary magazine, which eventually came out in two issues, in 1923 and 1924. Germinal, like the Dreadnought, published writers from all over the world, including India and South Africa, and took on an explicitly internationalist, anticolonial, and antiracist editorial position. In the 1930s, until the end of her life, Pankhurst turned her energy to Ethiopian anti-fascism and self-determination. Pankhurst founded another weekly newspaper, New Times and Ethiopia News, which connected antifascist organizing across Europe and Africa. She dedicated herself to independence in Ethiopia and Eritrea during and after World War II. Eventually, Pankhurst moved to Addis Ababa, where she was buried in 1960.70

Pankhurst was an outstanding figure but not alone among twentieth-century white British women in her participation in antiracist campaigns. In one key moment in the 1930s in Scottsboro, Alabama, nine young men were falsely accused of raping two white women; Ada Wright, mother of two of those accused, traveled to England to raise awareness of the miscarriage of justice happening in Alabama. The international organizing on behalf of Scottsboro engaged white British women like Naomi Mitchison, Vera Brittain, Nancy Cunard, and Lady Kathleen Simon. Cunard published a number of pieces related to Scottsboro in her 1934 anthology Negro, including her own essay “Scottsboro and Other Scottsboros.”71 She also organized a petition and letter writing campaign in Britain that garnered responses from writers including Storm Jameson, Rebecca West, and Hope Mirrlees.72 Even Virginia Woolf, who is not particularly known for her involvement in black diasporic politics, signed a public letter in support of the Scottsboro boys.73 These women worked alongside black British activists, including Jomo Kenyatta (then Johnstone Kenyatta), who served as a joint secretary of the Scottsboro Defence Committee, as well as members of the West African Students’ Union, the Negro Welfare Association, and the International Labour Defence London Coloured Committee. The moment of McKay working at Pankhurst’s newspaper in 1920 constitutes an early twentieth-century example of white British women confronting the violent implications of white womanhood.

London, it turned out, was not the place for McKay. McKay’s biographer Wayne Cooper and Robert Reinders’s article on McKay’s time in England reports that McKay left London shortly after Pankhurst’s imprisonment, feeling that the policing in Europe was getting out of hand.74 But perhaps the anxiety was even more personal. The central role of his article in the trial that put Pankhurst in prison may explain more specifically McKay’s anxiety around the police in London, and perhaps also his aversion to publicly claiming Pankhurst more seriously later on (dismissing her movement as “more piquant than serious”).75 Her trial and appeal, and the role of McKay’s reporting in the trial, reveals the perceived threat of the cross-fertilization of antiracism and socialism, as circulated in the pages of the newspaper.

McKay went on to the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, France, and Morocco, later in the decade. He continued to be occupied with the issue that motivated his letter to the editor in the Dreadnought. In 1922, he exchanged letters with Trotsky about the question of black troops in Europe that were “printed in Pravda, Izvestia, and other Moscow newspapers,” and which he included in The Negroes in America, a book first published in Russian translation.76 McKay highlights the importance of radical newspapers in London, describing a club to which he belonged, comprised of soldiers of color from Africa and the Americas. “I was working at that time in London in a communist group. Our group provided the club of Negro soldiers with revolutionary newspapers and literature, which had nothing in common with the daily papers that are steeped in race prejudice.”77 The Dreadnought offered alternative news for people of color in London, a city that McKay identifies, along with New York, as one of the “chief cultural centers of the West where Negroes hold mass meetings and discuss questions which interest them.”78 London would continue to be a cultural center for the African diaspora, with intellectuals including C.L.R. James, George Padmore, Una Marson, and Claudia Jones participating in newspaper projects that offered an alternative to dailies “steeped in race prejudice” in the coming decades.

Critics associate McKay with docklands—transnational, liminal spaces from which to articulate black diasporic views of the world, as he did in Banjo.79 His journalism from the docks of East London tends to be set aside (no doubt in part because he later disavowed organized socialist politics, and because Sylvia Pankhurst’s post-suffrage movement remains relatively unexamined). Nonetheless, McKay’s writings in the pages of the Dreadnought illuminate his strategies to refute racist beliefs about black sexuality and white womanhood. The pages of the Dreadnought provided a sympathetic platform to call out British labor leaders on their racism, and to offer black readers alternative analysis. He calls for those who claim to represent workers to be accountable to colonized people of color. McKay’s reply in the pages of the Dreadnought initiates an incisive protest, an instance of the empire writing back.

Acknowledgements

This article grew out of conversations with the late Jane Marcus. Funding from a Mellon Institute for Historical Research Pre-Dissertation Fellowship and a Graduate Center Doctoral Student Research award contributed to the work presented here. I also wish to acknowledge the peer reviewers whose feedback helped my revision, and editors Stefanie A. Jones, Eero Laine, and Chris Alen Sula.

Notes

- Claude McKay, “A Black Man Replies,” The Workers’ Dreadnought, April 24, 1920. ↩

- E.D. Morel, ““Black Scourge in Europe: Sexual Horror Let Loose by France on the Rhine,” Daily Herald, April 10, 1920. ↩

- Robert C. Reinders, “Racialism on the Left E.D. Morel and the ‘Black Horror on the Rhine,’” International Review of Social History 13, no. 1 (April 1968): 1, doi:10.1017/S0020859000000419. ↩

- Barbara Winslow, Sylvia Pankhurst: Sexual Politics And Political Activism, 1st ed., (London: Routledge, 1996), 128. ↩

- Jeffrey P. Green, Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain, 1901-1914 (London: Franck Cass, 1998); Gretchen Gerzina, Black Victorians/Black Victoriana (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003); Susan D. Pennybacker, From Scottsboro to Munich: Race and Political Culture in 1930s Britain (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009); Gail Ching-Liang Low and Marion Wynne-Davies, A Black British Canon? (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). ↩

- Vron Ware, in Beyond the Pale, notes that attention to white women who fought racism has been underdeveloped: “Whereas feminist historians have uncovered many examples of feminists who braved convention at home to fight to improve the lives and opportunities of women {…}, there has been little corresponding interest in British women who came face to face with the complexities of racism and male power.” Vron Ware, Beyond the Pale: White Women, Racism, and History (New York: Verso, 1992), 42. While this is less true today than when Ware first wrote this in 1992 (questions of women’s relationships to race and empire have informed recent scholarship in British modernism, for instance), this topic remains under-examined. ↩

- Pankhurst apparently suppressed McKay’s scoop that a sawmill that George Lansbury “owned or partially owned” was using scabs during a strike. Claude McKay, A Long Way from Home (New York: Arno Press & the New York Times. 1973), 78. Despite the importance of the story, and despite the Dreadnought’s general antagonism toward Lansbury’s Daily Herald and what it represented as the vehicle for mainstream British socialism, Pankhurst squashes the story. McKay surmises Pankhurst did so out of a personal allegiance to Lansbury, or because she owed some money to him. Later, when she criticizes McKay for a flattering profile of a leader of a union instead of interviewing rank-and-file members, he reflects on page 81 of A Long Way from Home, “I resented the criticism, especially as Pankhurst had suppressed my article on Lansbury.” ↩

- Jacqueline Jenkinson, Black 1919: Riots, Racism and Resistance in Imperial Britain (Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2009); Barbara Foley, Spectres of 1919: Class and Nation in the Making of the New Negro (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2003). ↩

- “Stabbing Negroes in the London Dock Area,” Workers’ Dreadnought, June 7, 1919, 1354. ↩

- “A Negro Poet,” Workers’ Dreadnought, September 6, 1919. ↩

- McKay, A Long Way from Home, 42. ↩

- Josh Gosciak, The Shadowed Country: Claude McKay and the Romance of the Victorians, illustrated edition (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2006). Gosciak also documents other links that McKay had to Britain. McKay had connections with Britain through his mentor in Jamaica, Jekyll, and Jekyll’s sister Gertrude, who facilitated the reviews of Songs of Jamaica (which included rich descriptions of nature, botanica, and landscape) in gardening magazines. Also, when McKay arrived in England, he contacted C.K. Ogden, with a letter of introduction from Walter Fuller. Ogden, in Cambridge, eventually published McKay’s volume of poetry with an introduction by I. A. Richards. This convergence of 19th century reformers, gay men, with McKay’s socialism and anti colonialism, points to another unexpected simultaneity that happens when one traces interpersonal connections. ↩

- Ibid., 53. ↩

- Ibid., 55. ↩

- Ibid., 43–44. ↩

- Gosciak summarizes these influences on page 1: “some of the dominant discourses in the late Victorian and early modern periods, such as internationalism, pacifism, the Arts and Crafts movement, decadence, Fabian socialism, and sexual rebellion.” These shared aesthetic influences may also help contextualize the traditional literary forms both Pankhurst and McKay each employed in their poetry. ↩

- Winslow, Sylvia Pankhurst; Richard Pankhurst and E. Sylvia Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst, Artist and Crusader: An Intimate Portrait (New York: Paddington Press, 1979). ↩

- John Marriott, Beyond the Tower: A History of East London (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011); Chaim Bermant, London’s East End: Point of Arrival (London: Macmillan, 1976). ↩

- “The Parties in the Streets,” Workers’ Dreadnought, August, 16, 1919, 1438. ↩

- E. Sylvia Pankhurst, Soviet Russia as I Saw It (London: “Workers’ Dreadnought” Publishers, 1921). ↩

- Morag Shiach, Modernism, Labour, and Selfhood in British Literature and Culture, 1890-1930 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 102. ↩

- McKay, A Long Way from Home, 77. ↩

- Workers’ Dreadnought, January 31, 1920. ↩

- Claude McKay, “Socialism and the Negro,” Workers’ Dreadnought, January 31, 1920, 1621. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Claude McKay, “‘Report On The Negro Question’ Speech To The Fourth Congress Of The Third Communist International, Moscow” in “McKay Essays on Race in the U.S.,” Modern American Poetry, accessed May 2, 2016, http://www.english.illinois.edu/Maps/poets/m_r/mckay/essays.htm; Robin D. G Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990). ↩

- Wayne F. Cooper and Robert Reinders, “A Black Briton Comes ‘Home’: Claude McKay in England, 1920,” Race 9, no. 1 (1967): 72; Wayne F. Cooper, Claude McKay: Rebel Sojourner in the Harlem Renaissance: A Biography (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1996), 114. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, Howard Eiland, and Michael William Jennings, Walter Benjamin Selected Writings Volume 4 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), 262. ↩

- Stuart Hall, Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order (London: Macmillan, 1978), 120. ↩

- Ibid., 120. ↩

- Ibid., 121. ↩

- Workers’ Dreadnought, April 24, 1920. ↩

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, New Edition (New York: Verso, 2006). ↩

- Norman Leys, “A Contradiction?” Daily Herald, 17 April 1920, 4. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- E.D. Morel, “Black Troops,” Daily Herald, April 21, 1920. ↩

- McKay, “A Black Man Replies.” ↩

- Claude McKay, Banjo, a Story without a Plot. (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), 277. ↩

- Ibid., 146. ↩

- McKay, “A Black Man Replies.” ↩

- Ware, Beyond the Pale, 37–38. ↩

- Ibid., 38. ↩

- Radhika Mohanram, Imperial White: Race, Diaspora, and the British Empire (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 36, http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=328378. ↩

- Ibid., 44. ↩

- Ida B. Wells, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972), 53. ↩

- Morel, “Black Scourge in Europe.” ↩

- Claude McKay and A. L McLeod, The Negroes in America (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1979), 77. ↩

- No author, “A New Horror,” Daily Herald, April 10, 1920, 4. ↩

- Morel, “Black Scourge in Europe.” ↩

- No author, “Black Troops Terror,” Daily Herald, April 16, 1920. Other coverage of this issue during this period in the Herald included “France’s Black Troops: Govt Shirks Issue,” April 15, 1920; “Black Soldiers ‘Withdrawn’ But Are Still There,” April 15, 1920. “A Semi-Ultimatum to France: British Ambassador Withdrawn from Allied Conference,” April 12 1920; “Black Peril on Rhine,” April 12, 1920. ↩

- Edward Morel, Coloured Troops in Europe: Report of Meeting Held in the Central Hall, Westminster, on April 27th, 1920 (London: Women’s International League, 1920). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Stabbing Negroes in the London Dock Area,” Workers’ Dreadnought, June 7, 1919, 1354. ↩

- Hazel Carby, “White Woman Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood” in Black British Cultural Studies: A Reader, eds. Houston A. Baker Jr and Manthia Diawara (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996). ↩

- Morel, “Black Scourge in Europe.” ↩

- Carby, “White Woman Listen!” ↩

- McKay, “Socialism and the Negro.” ↩

- Letter from Frederick Douglass to Catherine Impey, Bodleian Library of Commonwealth and African Studies, Oxford University. MSS Brit Emp S20. ↩

- Anti-Caste, John Rylands Library, Manchester University, Box 11, folder 23. ↩

- Fraternity, August 1894, 4. ↩

- Moira Ferguson, Subject to Others: British Women Writers and Colonial Slavery, 1670-1834, 1st ed. (New York: Routledge, 1992). Ferguson discusses the ties between Quaker women and abolition, rhetoric of women’s rights and its reliance on slavery discourse. ↩

- McKay, A Long Way from Home. ↩

- S. 000 (Gunner), H.M.S. Hunter, “Discontent on the Lower Deck,” Workers’ Dreadnought, October 16 1920, 1. ↩

- McKay, A Long Way from Home, 83. ↩

- “A Communist on Trial,” Workers’ Dreadnought, November 6, 1920, 1. ↩

- Cooper, Claude McKay, 123. ↩

- Leon Lopez, “The Yellow Peril and the Dockers,” Workers’ Dreadnought, October 16, 1920, 5. ↩

- Quoted in Barbara Winslow, “The First White Rastafarian,” in Robin Hackett, Freda Hauser, and Gay Wachman, At Home and Abroad in the Empire: British Women Write the 1930s (Newark, NJ: University of Delaware Press, 2009), 177. ↩

- E. Sylvia Pankhurst, “Appeal of Miss Sylvia Pankhurst against Sentence of Six Months Imprisonment {…} for Articles in the Workers’ Dreadnought.” Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst Papers, Folder 254, International Institute for Social History. ↩

- Winslow, Sylvia Pankhurst. ↩

- Nancy Cunard, Negro Anthology (London: Published by Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co, 1934), 243–268. A few years earlier, Cunard had publicly denounced her mother’s—and by extension British—racism in a pamphlet: Nancy Cunard, Black Man and White Ladyship. An Anniversary (Privately printed: Toulon, 1931, n.d., 11). ↩

- Cunard, “Scottsboro Appeal and Petition with Signatures, 1933,” n.d. Box 28, folder 6. Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. ↩

- “Scottsboro Case,” The Week-end Review, October 6, 1932, and clipped in Lady Simon’s papers at Oxford’s Bodleian Library of Commonwealth and African Studies, Oxford University. ↩

- Cooper and Reinders, “A Black Briton Comes ‘Home’.” ↩

- McKay, A Long Way from Home, 77. ↩

- McKay and McLeod, The Negroes in America, 9. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 8. ↩

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 13. Gilroy, on page 13 of the Black Atlantic: “The involvement of Marcus Garvey, George Padmore, Claude McKay, and Langston Hughes with ships and sailors lends additional support to Linebaugh’s prescient suggestion that ‘the ship remained perhaps the most important conduit of Pan-African communication before the appearance of the long-playing record’.” ↩