The body is a repository of metaphors and within its function of global exchange, its limits of fragility and destruction, the body serves as a way of dramatizing the social text. Olivier Mongin, in his important study on film and modernity, has said that there is currently an “economía de las imágenes de violencia… [en la que el sujeto] contempla una violencia imaginada en un laboratorio, una violencia in vitro que no le concierne.”1 This position, which is in dialogue with Susan Sontag’s notions on war photography in Regarding the Pain of Others, refers to media consumption of images based on the suffering of the other. The image consumed may cause pain and sometimes compassion. Yet, as images of violence are adjusted to the expectations of a market economy (which allows viewers that are sensitive to the phenomenon of violence the possibility of not having to deal with it closely), our protected emotional responses become a mechanism of convenient defense against this violence. In other words, Sontag warns us that we have become, “citizens of modernity, consumers of violence as spectacle, adepts of proximity without risk.”2

Within the economy of representation, the brutalized body has a complicated, yet privileged place. Much of the complexity that makes representations of violence move and disturb the viewer—but from far away—seems to come from the ambiguous status of the body as vulnerable and deserving of special care. This idea, though, also exists within an ambivalence regarding our contemporary understanding of the body. On the one hand, the body has more than ever acquired a status of universal protection, in large part by the declaration of the right to personal integrity as fundamental, which is in line with human rights discourses.3 On the other hand, as expressed by Judith Butler regarding the War on Terror, “some lives are grievable, and others are not; the differential allocation of grievability that decides what kind of subject is and must be grieved, and which kind of subject must not, operates to produce and maintain certain exclusionary conceptions of who is normatively human: what counts as a livable life and a grievable death?”4 This ambivalent dichotomy, in which the body is protected legally but in which certain bodies continue to be consistently and systematically violated, no doubt conditions the generation and reception of texts in the economy of images of violence.

What determines the value of a body, then, becomes the central question for the performances with which this essay engages. Piedra (Stone), by Guatemalan performance artist Regina José Galindo, deals in particular with the social abuse inflicted upon the female body. It was specifically created for the 2013 “Encuentro” of the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics in São Paolo, Brazil. Similarly, Corpos: Migraciones en la Oscuridad (Corpos: Migrations in the Dark) tackles this question as a performance piece/installation based on one particular aspect of the abused body: the trafficking of women and young girls for sexual gains. A co-production by three artists, Violeta Luna (Mexico), Mariana González Roberts (Argentina), and Rocío Solís (Spain), the piece was first presented at the Ibero-American Theatre Festival in Cádiz, Spain in 2011 and has since been presented in several countries throughout the Americas.

In the context of human trafficking and violence against women, I am particularly interested in the ways in which performance practices can become avenues for producing political expressions that, at the very least, become a form of protest and evidence for the manifestation of ideas that could otherwise remain invisible (as unspeakable horrors).5 Are theatre and performance able to aesthetically transform political ideas into creative images that lead to awareness and social action? With regard to female sex trafficking, the reality is particularly dire, as these women function in a stateless limbo where they are often regarded as “illegal migrants.” Even as most have been forcefully removed from their country of origin, they exist in systems of coerced migration for the purpose of exploiting their bodies.6 This network of modern day slavery, which controls its victims through psychological and physical violence, is tied to a culture of gendered violence and misogynistic values that global society, and Latin American society in particular, has been unable to overcome. Trafficking is a growing transnational process; the primary victims are women precisely because they are unprotected by the state. As Janice Phaik Lin Goh explains, “women are objectified and commoditized, deprived individual rights, and they are seen as an ‘anomaly’ by the state, law, and society.”7

Adding to this history of violence are neoliberal practices of commercial expansion that promote the displacement of and systematic rape and violence against women (especially indigenous women) as multinational conglomerates seek to use land and resources in Latin America for economic gain. Thus, in this constant search for wealth, as Saskia Sassen has said when talking about the “survival circuits” of the global south: “Prostitution and migrant labor are increasingly popular ways to make a living; illegal trafficking in women and children for the sex industry, and in all kinds of people as laborers, is an increasingly popular way to make a profit.”8 For the purposes of this essay, I want to consider the ways in which performance activists have engaged politically, socially, and culturally with this prevalent issue that tragically connects women (in particular) throughout the world in a web of economic exchange. Precisely because the voice of the victim is not heard through the language of the state and economic capitalism, the aesthetics of performance can provide the conceptual structures to hear those voices, even if it is dependent on something as basic as producing a moment of awareness in the spectator. Piedra, the performance piece by Galindo, allows for a more abstract reflection on the subject of violence inflicted upon women, while Corpos presents a more specific and tangible discussion of sexual violence and human trafficking. Even though both pieces deal with similar themes, in terms of the ethics of spectatorship to leverage justice they are fundamentally different. Whereas the audience of Corpos is asked to reflect on and engage the theme of human trafficking and violence against women in a prescriptive and literal sense, the spectators of Galindo’s piece can simply watch the performance, leaving the piece without a concrete space for reflection in the immediate moment.

Piedra

In Galindo’s performance the artist’s body remains motionless, covered in charcoal, like a stone. Throughout the thirty-minute performance she never moves, even as two male volunteers (fellow artists whom Galindo had previously contacted and who have agreed on the choreography of the piece) and one improvised female audience member (an unexpected participation) urinate over her still body. The performance begins when a small, thin woman (Galindo) covered in charcoal from head to toe walks through the outdoor patio where the spectators have gathered. She stops in the middle and curls into a ball on the hard floor. As she bends down and rounds her back, knees and elbows cuddled against her ribs, an assistant covers the last piece of visible skin (the soles of her feet) with charcoal. The aesthetic choice of using charcoal to cover her body is, of course, a reference to the violent abuses of the mining industry in Brazil as well as many other Latin American countries, where often the most exploited victims of this colossal industry are female laborers trapped in a structure of violence and economic ambition that affects their health and livelihood.9 Completely covered with coal, the body of the artist remains motionless, her face buried in the palms of her hands. The audience around her, who at first brought out cameras and other recording devices to capture her always-intense performances, remains quiet around her, awaiting an action from the artist. Yet, the artist remains motionless.

This series of actions forms part of her overall performance poetics regarding the suffering of the female body. In a poem she wrote as part of this performance (which is not recited, but a part of the performance dossier), she states:

Soy una piedra

no siento los golpes

la humillación

las miradas lascivas

los cuerpos sobre el mío

el odio.Soy una piedra

en mí

la historia del mundo.10

Working with these metaphors, Galindo is able to produce a very literal performance (regardless of its aesthetic abstraction) about violence and pain, humiliation and exploitation. The purpose of Galindo’s piece is quite obvious, as she explains when talking about her performance:

Sobre el cuerpo de las mujeres latinoamericanas ha quedado inscrita la historia de la humanidad. Sobre sus cuerpos conquistados, marcados, esclavizados, objetualizados, explotados y torturados pueden leerse las nefastas historias de lucha y poder que conforman nuestro pasado. Cuerpos frágiles solamente en apariencia. Es el cuerpo de la mujer que ha sobrevivido la conquista y esclavitud. Que como piedra ha guardado el odio y el rencor en su memoria para transformarlo en energía y vida.11

It is only through the figurative (and poetic) transformation of woman into stone that she can narrate the history of violence against Latin American women (and women in general). Considering the multitude of instances of violence in her own country of Guatemala, Galindo was particularly inspired in this piece by the ways in which pain can be somatized as a form of social criticism. This is especially true if one is to consider that what Galindo sees as the constant violence in her society, though directed primarily at men’s bodies, has a different dialogue when it is conducted though the bodies of women. Galindo’s performance represents the most common scenario of violence: “Cuando se hacen análisis, la cuestión es que a los hombres se les dispara siempre, y los cuerpos que han sido asesinados amanecen con un tiro de gracia. A la mujer, previamente a asesinarla, siempre se le tortura, generalmente a través de violencia sexual.”12 The bodies of women, then, suffer an additional humiliation: they are marked by rape to prove that they are a surface upon which to describe a systematic practice of pain and injustice in a failed political and social globalized project of economic expansion. In the performance, Galindo aims to represent the tension found in those moments of humiliation and to take that pain to an extreme in order to annihilate the individual and leave only a body.

As a radical practitioner of body art, Galindo uses her own body as a tool for social and political action. She has often described her work as a way of constructing a “human bridge” between people and places, oftentimes using spaces that carry a significant weight of violence and abuse. Galindo, at least for a moment, is able to resignify or denounce the actions upon these spaces through her performances, which allows for a more empathic understanding of power, life, and death. In Piedra, Galindo links a history of environmental exploitation with a colonial structure of dominance and abuse against the bodies of women. Thus, the tragic narrative of a nation (in this case Brazil, though it can be extended to many other countries) rests on the abused body of one woman. Throughout the performance, her body does not move, and ten minutes after the start a man, who appears as part of the group of people that have accumulated around the artist (though he is one of the aforementioned artists who is part of the performance), breaks off and walks toward her. He unzips his pants, pulls out his penis, and proceeds to urinate on that motionless and blackened body.

This is, obviously, a very shocking and violent image: the stream of urine draws grooves and channels down the charcoal that sticks to her body, dripping down to her face and falling off her fingers. The absolute silence around the action itself (which extends to the audience who only observes without outward expressions of emotion) forces the question of how to communicate or make visible trauma and abuse if language is taken away. As spectators of this action, we are only left with the sensorial: a communicable experience of trauma. This is an experience of pain and humiliation that elicits a sense of subordination on the part of the artist complicit with the submissive positionality of Latin American women as perceived by most of society. Galindo’s piece is problematic precisely because it re-produces scenarios of violence through a performance practice which is later justified by the reflection from the audience. Even though Galindo’s point of departure is to denounce violence through a violent act itself, the issue of spectatorial ambiguity remains. This leads to the questions: Is a horrible act represented or repeated again when it is allowed to happen without resistance—especially when witnessed by a group of people who become a “public”?

The pain and humiliation present in the performance remind us that a misogynistic society has taught us that women are conquered through emotional and physical pain or, as Veena Das explains, “pain is the medium through which society establishes ownership of individuals.”13 Thus, Piedra connects with the spectator through a voyeuristic relationship established around the action itself. We are witnesses to the pain and suffering of the artist, while the temporal demands of the performance makes us aware of the options we have as we choose to remain present or not during the piece: to stay might imply enduring, in a way, “along with” Galindo. The cruelty we are actively experiencing acts as a signifier of a Latin American reality, and the vulnerability of her body (which appears to have no agency before the actions thrust upon it) has an obvious affect upon the observers.

In Piedra the performance itself is not the artist’s body, but the action that this body allows upon it. As it lies there, exposed, it loses any form of control or agency, and this opens the way for the spectator to be exposed as well. We stand around this vulnerable body in silence, unwilling to intervene (because we are aware of the role of the audience as observer), but receiving the impact of such an action. At the same time, one must recognize the possibility of identifying with both sides, and this raises the question: if one identifies with the woman/stone while at the same time recognizing a possible identification with the man who urinates on her body, what imaginary mechanisms are mobilizing this identification (in relation to issues of abuse and power)? Does this imply competing scopic regimes that we strive to mediate to maintain a sense of morality? What is the potential for audience members to reflect on issues of accountability and justice in relation to the witnessing of violence?

In this sense, the performance constitutes a marker of that which is most horrific in society (violence and trauma), but it appears through an abstract image to achieve a different affect upon the observer: to make the audience a witness or at least allow for the possibility of questioning our reactions to the piece as a witness who is concerned with the action before them. This is in line with Giorgio Agamben’s notion of the potentiality found in the witness for the possibility of commitment and responsibility:

[T]estimony is the disjunction between two impossibilities of bearing witness; it means that language, in order to bear witness, must give way to a non-language to show the impossibility of bearing witness. The language of testimony is a language that no longer signifies and that, in not signifying, advances into what is without language, to the point of taking on a different insignificance–that of the complete witness, that of he who by definition cannot bear witness.14

Thus, at the very least, the performance brings out the possibility of responsibility from the audience as witness. As difficult as it is to gauge audience reaction in this piece, the silence, stupefaction, and clear discomfort of those around Galindo when I saw it showed a shared intentionality as we were each clearly affected by the piece and those around us shared in the same moment. Piedra forces us to face the pain of other lives, to think of another, and, as Ileana Diéguez observes, “if we think and reflect from a space of pain without being direct victims, perhaps we are realizing that under the current conditions the inability to think of ourselves or imagine ourselves separate from the victims intensifies.”15 In other words, we cannot readily choose between identifying or distancing ourselves, and this ambivalence produces the critical effect of the piece.

Ten more minutes pass by and Galindo continues perfectly immobile in the same position on the ground. A second man steps forward from the audience (again, a fellow artist who was part of the piece) and urinates onto her body. The clear lack of concern with which these men urinate on her points to the widespread apathy that is often found in regards to the safety and care of a woman’s body. This theme is also a major concern within Galindo’s artistic oeuvre. In Piedra the female body is represented as a stone precisely because both are objects conditioned (by nature and society) to withstand violent acts. Galindo chose the parallel between woman and stone precisely because she wished to negate the individual (as the act of violence does) but not the live body itself. And a stone is a natural object, which is characterized by its resilience. Even as this body in the performance is in a completely submissive position, what allows it to continue is the resilience with which it faces the humiliation and violence imposed upon it. The ease with which a man (whether it be within the performance or outside of it) is able to contaminate the female body through an apparently superficial action, such as emptying their bladder, is paralleled to the everyday violence that the female body encounters as it functions in the social order. This violence emphasizes the unconscious nature of everyday actions that drive a repetitive structural violence.

Thus, this “stone woman” is, at the same time, an ancient and natural structure (a timeless part of nature) and it performs as a disposable object of inherent exploitation. Galindo’s body becomes an emblem of disposability, as useless as a stone on the road. Even more so, this performance in Brazil carries an additional connotation: these disposable bodies also include the workers in the huge industry of coal mining, which is the largest non-renewable energy resource in the country and the leading cause of water and land pollution. Besides the environmental damages brought on by multinational corporations that seek to find ways in which to augment their economic gains by exploiting foreign lands, there is the tragedy of women being raped and killed for protesting the expansions of these conglomerates. The two issues are tied together, as women are often the primary victims of sexual violence in the efforts to conquer economic expansion.16 Piedra, by means of a simple yet poetic action, manages to capture a local and global crisis: the harmful effects of coal mining on the environment, the plight of the exploited workers, and widespread structural violence against women that economic exploitation perpetuates.

Galindo has said that the history of violence has been recorded on the bodies of women, and this notion is complicated towards the end of the performance by an additional performer. The action of men urinating on the female body aligns femininity with nature and the bodies of men with the processes of violence and exploitation. Ten minutes after the second man has urinated on Galindo’s body, a third figure steps forward. This time it is a woman who comes toward the artist, plants her legs on either side of the stone/body, and urinates. It must be pointed out that this third volunteer was an unexpected participant, as she was not a part of Galindo’s performance, but someone from the audience that decided to participate. In the original piece, a third man should have urinated on Galindo’s body, but he was unable to because of this unknown woman’s interference. The piece was carefully timed, so Galindo herself was not aware of this until after the performance, though she admits that this made it more interesting. The participation by this unknown woman reconstructs the argument around a male body perpetrating violence against a female body and at the same time implies that women are complicit in an intra-sexual violence. With this, Galindo’s criticism folds back on itself to question the ways in which women enact violence on the bodies of other women.

The unexpected participation of this woman also raises important issues regarding agency and control in the piece. As an artist, Galindo has the agency of choreographing the elements of the performance. Yet, this unscripted moment takes away her own agency as she is left to experience an instance outside of her own control. Galindo’s form of artistic agency is complicated for a single moment through the act of this woman from the audience. After a pause, Galindo slowly gets up and walks past the audience. The spectators are left behind. They watch her walk away as well as the trail of urine that she leaves in her wake. An important part of this performance is its framing: Galindo chooses to assume the position/identity of a stone at the beginning, but she is able to get up and walk away from it at the end. This action appears to indicate the strength and agency of women in spite of the violence done to them. Of course, one must acknowledge that Galindo’s performance allows for the possibility to have this violence inflicted upon her in a momentary way through her own choice, whereas women who are subject to violence do not have that form of agency and protection. Women and stones share the ability to take abuse from their environment and survive continuous wear. Galindo’s Piedra presents the images of women who suffer from an abject abuse for the purpose of reorganizing the vectors of power between the victim and the victimizer, while at the same time emphasizing the durability of the female body and spirit.

Corpos: Migraciones en la Oscuridad

This implicit pact between performer and spectator (as potential witnesses) is also a fundamental element in Corpos: Migraciones en la Oscuridad. The performance by Luna, González, and Solís is composed as a series of galleries in which different aspects of the business of sex trafficking are explored along with its monetary, personal, emotional, and psychological consequences. It functions as a mixture of performance art, art installation, audio installation, and theatre that allows the spectator to be introduced into an ethical disjunction promoted by the consumption and economic gain of trafficked sexualities. In the performance, spectators are ushered through a scripted path that leads them through several rooms. Within these rooms, viewers are presented with images, scenarios, and poetic representations of sexual trafficking. Through the simplicity of its construction, these artists are able to implicate a double subjectivity for the audience, which provokes a sense of ambivalence similar to the process found in Galindo’s piece.

At the beginning, audience members are standing in line to enter into the performance space: they are stamped on whichever part of the body they wish with the word “CORPOS.” In the first room/scene, “General Meeting for the Shareholders,” we are asked to take a seat. This becomes the conference room of the corporation CORPOS, where we are informed of our role as shareholders in one of the most successful companies in the world. From that moment on, as we travel through the different rooms of the performance space, we are framed by the fact that we inhabit them as shareholders in this company. The objective is clear: as performance artists and activists, the performers utilize the space to establish a dialogue with those violent practices that tragically connect different bodies at a global scale within a network of economic exchange. That is why it is important from the beginning that we be informed of the profits that are made from trafficking in women and how well the company/we is/are doing. We then move on to the second room, where we drink wine and toast the company’s success; we are transformed into the beneficiaries of sexual exploitation.

As we continue through the rooms that explicitly suggest different references and metaphors for human trafficking, we are disturbed by this identity we have willfully accepted as part of this suspension of disbelief. We inhabit the entire performance through this double discourse, as an audience member and a shareholder. But this double discourse also binds us together: we are not alone within the horror of the things that we are looking at and experiencing. This was one of the more interesting aspects of the installations, as audience members reacted in different ways to what we were all seeing, but were also aware of the “safety” afforded by experiencing these actions as a group. For example, one room staged the raping of a young girl: there was a pair of underwear on the floor that obviously belonged to a little girl, and one could hear a wheezing sound and see part of a mattress on the floor. The door was ajar, yet there were people who pushed it, in an attempt to see what was inside, which would mean wanting to see how this girl is raped.

This is not to say that those who tried to push the door open were simply perverse, but it helps us to understand the disturbances that the piece imposes on the audience member. Besides the (potential) desire/curiosity to see the rape, there are other possible readings for this spectator’s action. The performance, as an avenue for political expression, allows the spectator a means through which to enact and rehearse embodied awareness and a possibility for social action when confronted with different stages of sexual and gendered violence. The observer has the potentiality for acting as participant. That is to say, the audience who experiences Corpos as a performative act is pushed to question the conventional distinction between “victim” and “aggressor” as it seems ill-suited to fully explain the results of this type of violence: (1) as a simple viewer who sees these things from a place that is not frequently seen, and (2) having accepted a welcome card, being stamped, having toasted, and so on, implicated as complicit in the benefits of this trade. What seems to be at the core of the performance is a clear call to reflection on our part, because without customers and without a society that consumes people, this horror would not be possible. And, for a moment, the spectators are allowed to perform an interruption through their own actions (trying to open the door).

As the artists themselves have explained, the double discourse was a fundamental part of the performance. There is more to this than simply including the audience: it has to do with the fact that we are part of a system that more or less consciously includes us, and we share a responsibility in the existence of these horrors. As Luna explains,

Uno de los puntos fundamentales fue ver a esta mujer no como víctima sino como una sobreviviente dentro de un contexto social opresivo. Y que nosotros como espectadores sociales tenemos responsabilidad sobre esto, que cada acción, así como consumir pornografía, o seguir reproduciendo los estereotipos de género, automáticamente nos implica en esto.17

This is not to deny that in specific scenarios certain parties take on an active role in the perpetuation of sexual violence, nor is it to ignore the destructive, often deadly intentions behind such actions. Rather, in the performance one can find an effort to situate the horror of sex-trafficking within a network of conflict whose complexities are forgotten in the binary language of domination and resistance. Conceiving of human trafficking purely in terms of cause and effect—and organizing against it around the theme of victimization—oversimplifies the intricate problem of human trafficking within a globalized and modern world.

This very important issue of audience response was closely related to the artists’ recognition of the ethical connotations of representing the violence of this subject onstage. As the three artists agreed, there was a constant effort to avoid the victimization of the women whose stories they aimed to present—an effort that closely relates to what Wendy Brown contends through her concept of “wounded attachments.” Brown argues that when we organize around identity, or what she names our “wounded attachments,” we are compulsively repeating a painful reminder of our subjugation, and maintaining a cycle of blaming which continues the focus on oppression rather than transcending it. The desire to hold on to identity categories is a notion that is at the core of many contemporary political claims that radically de-historicize the experience of suffering and of harm, and in the end reproduce the spectacle of various communities as defined by the aggression that has affected them. In this way, “Persons are reduced to observable social attributes and practices defined empirically, positivistically, as if their existence were intrinsic and factual, rather than effects of discursive and institutional power.”18 The purpose of the performance is precisely to avoid such a characterization, as Mariana González Roberts explains:

Desde un principio coincidimos en que no presentaríamos casos puntuales, esas historias que son terribles la mayoría. Más bien buscamos entender que todas estas mujeres no son esta imagen que tenemos de seres que no tienen historia, que es lo mismo que les pasa a los inmigrantes, cuando dejamos nuestro país nos convertimos en “inmigrantes” nada más, cuando en nuestro país éramos alguien que tenía una vida, una historia y una serie de detalles. Ahora de repente formas parte de un colectivo. Es decir, ahora eres un inmigrante, ahora eres víctima de la violencia, ahora eres víctima de la trata.19

So instead of specific stories, the performance evokes a series of emotions centered on poetic images that refuse to define an individual who is absent from representation.

This dependence on images is obvious from the beginning of the performance. In the second room, as we finish our toasts, the table from which we took our wine glasses becomes illuminated from below and we can see a series of figures hanging under the table, followed by a woman’s face with her mouth taped off, looking straight at us. This is an intricate image on the politics of visibility. The momentary appearance of this woman does not provide us with a particular narrative text; instead we are forced to recognize the emotions she has provoked. Since the route throughout the performance space is a movement through different rooms, the piece seems to articulate a structure based not on a traditional theatrical dramaturgy, but rather on a museum dramaturgy. The space is conceived from the visual arts perspective, as an installation space, a space that is intervened in or acted upon. The artists do not inhabit the space; instead the performance itself becomes a constant intervention upon the space. Each room has its own identity, and it is up to the audience to create a narrative for each space, as the movement through the rooms becomes a journey aimed to generate a personal consciousness. A wonderful example is the third room in the piece, “Intimate Landscape.” It consists of a bed placed at an angle, a table with make-up and other discarded items, and a small closet with clothes. Each object has a recording in a very low voice that emanates from it. These objects become an extension of the absent body and the testimonial of those who are not there. In this way, the performance does not look for the morbidity that could be found around the subject of human trafficking. Rather, it proposes a series of sensations and images in relation to what happens in these horrendous situations. There is a presence/absence of the person, who does not appear, but this telling/claiming through objects can attest to the history of each particular suffering. The complex process of witnessing is further problematized as we, the audience, are prevented from “direct” contact with the “victim.” This is a particular quality of violent acts that Patrick Anderson and Jisha Menon consider: “Despite the potential for empathy facilitated by the photograph or the videotape—the sense that we, after looking, have ‘really been there’—it is the experience of suffering that is most considerably lost when images of violence inundate the visual realm, acting as surrogates for productive transnational discourse. Violence, then, acquires its immense significance in a delicate pivot between the spectacular and the embodied.”20 What appears in the performance is not a victim to be pitied in a generalized manner; instead we find a subtle beauty that shows a very painful life story through objects and actions.

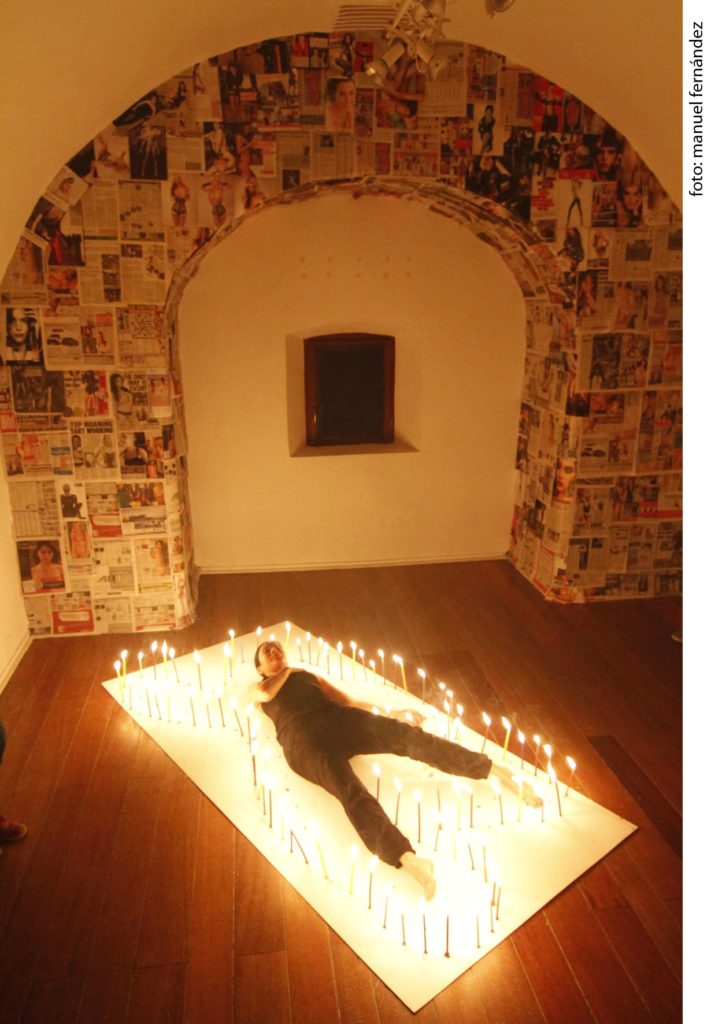

The inclusion of beauty (physically and poetically) within this representation acquires a greater purpose, as it carries great weight. The artists agreed that beauty became a crucial element that sustained them. As Rocío Solís explains: “Es un elemento que nos sostiene en el sentido de que no nos deja caer sólo en el horror del tema que se trata, sino que también nos cuenta la complejidad del ser humano, que es capaz de generar ese horror y también es capaz de generar belleza y humor.”21 For example, in the gallery titled “The Erring,” a woman (Luna) lays still on the floor surrounded by lighted candles. The candles provide her “body outline.” She suddenly stands, walks to a window, opens it, and a beautiful ocean view appears (note that this scene was only possible in the space used in Cádiz, that allowed for such a view). The walls in this room are plastered with newspapers offering grotesque and violent stories of death. Beauty is also a part of the representation of woman as object. In another room, the audience enters a space with an enormous gift-box in the middle. Upon closer inspection, we can see that it has a glass top and inside there is a beautiful woman (Solís), impeccably dressed in elegant lingerie. As an audience member, you can approach this box and observe/admire the woman inside. At the same time, a continual loop of world economic news is played throughout the room. This is the essence of human trafficking in the globalized world.

As Lydia Cacho asserts, to fully understand human sex trafficking we must acknowledge that mafias are now legal corporations, that prostitution is a successful industry, and that women and children are the primary product to be sold. The mafias that enable human trafficking are a clear part of the nation state structure, since the laws against them are disconnected from cultural changes and because the twenty-first century is experiencing a backlash against feminism. Misogyny is clearly back, strengthened and with new marketing strategies; and really, it never left in many countries, it was simply disguised in politically correct discourses.22 We are part of a global culture that promotes the objectification of people as an act of liberty and progress for capitalism. Many women live enslaved before a dehumanizing market economy, imposed as our manifest destiny, and many assume prostitution is a minor problem, ignoring that within it lays human exploitation.

It is through the perturbed nature of these instances of beauty that sexuality acquires a different meaning. In the performance, any instance of eroticized sexuality disappears, so that we are left with an empty sexuality. In the gallery “The Lines of Memory,” a young girl (Luna) appears among clotheslines, where clothes and bags filled with red liquid are hanging. She puts on a wig, smiles at the audience scattered around the room, grabs one of the bags, and proceeds to suck on it with brutal force. Her pain and discomfort at this self-inflicted action is obvious until the bag explodes and stains her white dress with the red liquid. Luna takes off the dress and moves around the room, hanging different members of the audience by their clothes and even their hair onto the clotheslines with pins, reflecting her violation, lack of freedom, and exhibition upon them. The scene is an obvious reference to the oral sex practices that are so common among child trafficking. Yet, the significance of the gesture is in the refusal to represent the practice in a literal manner; the performance does not focus on the pedophilic and erotic real event. Instead, there is a poetics to the act that visualizes a series of narrative possibilities. The images evoked in this space fit well with the next room, “Table Dance,” where a woman (González) enters, puts on a pair of red heels, and abruptly takes off her dress. She stands naked before the audience and begins to dance seductively, but in a mechanical manner, while looking at each person intensely. All the while, different testimonies from sex-trafficking victims are projected upon the wall, and by extension, her body. When this naked woman intervenes upon the space, as an image that usually evokes an eroticized sexuality, the audience reacts in the opposite manner. Her naked body is “too close” to us; she looks directly into our eyes and it seems to fill us with shame. This is very similar way to how Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick describes it: “Shame floods into being as a moment, a disruptive moment in a circuit of identity-constituting identificatory communication. Indeed, like stigma, shame is itself a form of communication.”23 As we turn our faces and we avert our eyes the audience becomes aware of the trouble with the situation, or at least of the inverted power dynamics. This causes a sense of vulnerability, which increases with the message projected upon on González Roberts’ body and the wall.

In our everyday lives, we are constantly bombarded with images that show physical violence, which clarify how we are less protected as citizens. By placing political action as its central objective and presenting the vulnerability of the body, these performances make it possible to perceive an instance of healing through the recuperation of agency in the traumatized body. Thus, for a moment we are made aware of our own vulnerability. It is true that the law, as well as the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), says many things, but actual politics and economic crises establish a different reality. Besides creating policies, none of the international organizations that we assume protect human rights (ONU, UNESCO, OTI), do much concrete action to avoid violations. It is because of this reality that theatre and performance are and will be a necessary tool to expand and share these experiences of pain and shame. These instances of performance are one of the few ways that remain in force to carry out the notion of community as defined by Ileana Diéguez, when she says: “The representations of the absences, the staging and theatrics of pain, the performativities displayed by the communitas of mourners, are all forms of action for life, symbolic practices that emerge in the public space to make others visible, striving to give them a symbolic body against all the projects of disappearance and annihilation of individuals.”24 We live our lives before a sinister and contradictory message, which pushes us to become stronger and more “independent” (as a euphemism) consumers through neoliberal politics, while we are transformed into more vulnerable and unprotected citizens, not by the law, but by a permanent state of exclusion. To leverage justice for women under these circumstances is a difficult task, but these performances do that work through their insistence on public complicity and responsibility for these crimes against women, and indeed, against humanity.

Notes

- “economy of images of violence… {in which the subject} observes an imaginary violence in a laboratory, a violence in vitro which does not concern him or her.” Olivier Mongin, Violencia y cine contemporáneo: Ensayo sobre ética e imagen (Spain: Editorial Paidós, 1994), 141-3. This and all subsequent translations are mine. ↩

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003), 111. ↩

- It is important to consider that the nature of human rights is curious, as it is often met with suspicion even as it enjoys the support from various groups across the world. This is largely due to concerns about Western power, especially in societies that were ruled by colonial powers in the West. As Mark Hannam has explained, “It has become a commonplace strategy to appeal to human rights in order to make legitimate the case for political change; such strategies are used not just by the leaders of popular movements against their own governments, but also by governments themselves seeking to justify their interference in the domestic affairs of other states.” Mark Hannam, review of On Human Rights, by James Griffin, Democratiya 15 (2008): 115. This is especially so because, despite the human rights tradition having originated in the West and being based on Western values, it claims universality. Thus, the discourses of human rights are often found at the core of violent interventions upon “under-developed” and “non-Western” nations as a challenge to their sovereignty in the name of human rights violations—even as these challenges often lead to the death of large numbers of civilians. ↩

- Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (New York and London: Verso, 2006), 46. ↩

- Although the performers in my case studies are of Latin American and Spanish descent, their pieces are created not to represent specific cultural or geographical manifestations of violence. Rather, these performances approach the topic of violence against women on a global perspective that acknowledges that these acts occur in various forms throughout the globe. ↩

- The United States’ Trafficking Victims Protection Act defines human trafficking as the “recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons by force, abduction, fraud, or coercion for forced or coerced labor, servitude, slavery, or sexual exploitation.” Quoted in “Trafficking of Women: U.S. Policy and International Law,” WeDo.com, last modified October 5, 2016,http://www.wedo.org/wp-

content/uploads/trafficking. . ↩pdf - Janice Phaik Lin Goh, “Deterritorialized Women in the Global City: An Analysis of Sex Trafficking in Dubai, Tokyo and New York,” intersection 10, no. 2 (2009): 273 ↩

- Saskia Sassen, “Global Cities and Survival Circuits,” in American Studies: An Anthology, ed. Janice A. Radway, Kevin K. Gaines, Barry Shank, and Penny Von Eschen (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), 188. ↩

- The abuses of the coal mining industry are present in various countries of Latin America, including Galindo’s own nation of Guatemala. Since Galindo creates pieces based on the history of the country where she will perform them, she chose to focus on the exploitation of the mining industry in Brazil. Regina José Galindo, interviewed by Analola Santana, October 22, 2015. ↩

I am a stone

I do not feel the blows

The humiliation

The leering stares

The bodies upon my own

The hate.I am a stone

Upon me

The history of the world. ↩- The history of humanity has remained inscribed on the bodies of Latin American women. On their bodies—conquered, marked, enslaved, objectified, exploited, and tortured—one can read the terrible stories of power and struggle that shape our past. Bodies are fragile only in their appearance. It is the female body that has survived conquest and slavery. Like a stone, it has stored the hatred and rancor of memory in order to transform it into energy and life. Regina José Galindo, “Piedra” (Performance documents from the “Encuentro” of the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics, 2013). ↩

- “When one conducts an analysis {of the situation}, the point is that men are always shot, and the murdered bodies appear the next day with a mercy shot. Women, on the other hand, are always tortured before they are murdered, and that always equals sexual violence.” Regina José Galindo, interviewed by Analola Santana, October 22, 2015. ↩

- Veena Das, Critical Events: An Anthropological Perspective on Contemporary India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995), 35. ↩

- Giorgio Agamben, Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive (New York: Zone Books, 1999), 39. ↩

- Ileana Diéguez, “Communitas of Pain: Performativities in Mourning,” (Re)Positioning the Latina/o Americas: Theatrical Histories and Cartographies of Power, eds. Jimmy Noriega and Analola Santana (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press), forthcoming. ↩

- A recent example can be found in a New York Times article that describes the gang rape of, at least, ten Mayan women in Guatemala at the hands of men who were evicting people (and setting their houses ablaze) from the village for the Canadian mining company Hudbay Mineral Inc. As the article states: “In a 2014 report, the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, a policy group in Washington, concluded that Canadian companies, accounting for fifty percent to seventy percent of the mining in Latin America, were often associated with extensive damage to the environment, from erosion and sedimentation to groundwater and river contamination. Of particular note, it said, was that the industry ‘demonstrated a disregard for registered nature reserves and protected zones.’ At the same time, the report said, local people were being injured, arrested or, in some cases, killed for protesting.” Susan Daley, “Guatemalan Women’s Claims Put Focus on Canadian Firms’ Conduct Abroad,” The New York Times, April 2, 2006, accessed July 20, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/03/world/americas/guatemalan-womens-claims-put-focus-on-canadian-firms-conduct-abroad.html?_r=0. ↩

- “One of the key points was seeing this woman not as a victim but as a survivor within an oppressive social system. And to reflect how we as viewers have a social responsibility for this. Each action we take in our everyday lives, such as consuming pornography or continuing to reproduce gender stereotypes, automatically involves us in this issue.” Analola Santana, “El registro de la memoria: una entrevista con Violeta Luna, Rocío Solís y Mariana González Roberts,” Notas de dirección, ed. Dora Sales (Cádiz: Asociación Cultural Sorámbulas, 2012), 202. ↩

- Wendy Brown, “Wounded Attachments,” Political Theory 21, no. 3 (1993): 399. ↩

- “We all agreed that we did not want to present specific cases, which we all know are horrific stories for the most part. Rather, we wanted to create an understanding that all these women are not simply victims who have no history, which is the same thing that happens to immigrants outside their country, we become ‘immigrants’ only, while before we were someone who had a life, a history and a great number of details. Now suddenly you’re part of a collective. That is, now you’re an immigrant, you are now a victim of violence, now you are a victim of trafficking.” Santana, “El registro de la memoria,” 215. ↩

- Patrick Anderson and Jisha Menon, Violence Performed: Local Roots and Global Routes of Conflict (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 5. ↩

- “We acknowledge the complexity of the human being, who is capable of generating such horror and is also able to generate beauty and humor,” Santana, “El registro de la memoria,” 216. ↩

- Lydia Cacho, Esclavas del poder, un viaje al corazón e la trata sexual de mujeres y niñas en el mundo (México: Editorial Grijalbo, 2010), 170. ↩

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke UP, 2003), 36. ↩

- Diéguez, “Communitas of Pain,” forthcoming. ↩