In the contemporary globalized world, the life stories of marginalized and vulnerable peoples play a crucial role in attempting to leverage justice. Charities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and other bodies concerned to “raise the voices” of asylum seekers, displaced peoples, and victims of abuse flood the internet and other media with written and filmed testimonies in attempts to build public awareness of their plights and support for their cases. Conversely, these voices and those who seek to advocate for them can be swiftly dismissed or fiercely derided. Often, the telling of their stories represents an opportunity to those whose fate is partly determined by the way that their lives are perceived by others to rebalance how their actions and motivations are presented. Their testimonies can help to combat the “demeaning or contemptible” picture that leads to the “misrecognition” (emphasis original) identified in the 1990s by Charles Taylor as a form of “oppression” of minority groups.1 Crucially, the practice can affect the decisions taken whether or not to grant access to legal and civic rights. In the context of live performance, as Harry Derbyshire and Loveday Hodson argue of verbatim forms, testimonies can exert affective pressures on their witnesses, triggering recognition that might influence the acceptance or rejection of a person’s claims.2

This article is focused on the performance of testimony, and the intersections of this mode of conveying life experience with established narratives and existing discourses that influence the degree and quality of recognition individuals receive as humans. As well as acknowledging their affective influence, it assumes that examining the mechanics of making performance from life stories can reveal some of the cultural and economic tensions that underlie the granting of rights upon which a safe and decent life depends. As David Michael Boje and Grace Ann Rosile indicate, storytelling and narrative representation are “powerful ways to trace the forces that push and pull people, organizations and communities.”3 In exploring the way that producers and practitioners attempt to leverage justice through the mechanics of making and telling the stories of vulnerable individuals, I will indicate how the shaping of testimonies by theatre practitioners is sometimes complicit with the globalizing tendencies of Western ideology, and particularly with narratives that tend to emphasize economic potential and a moral sense of deservingness. At the same time, I will illustrate how the ethos and practice of personal respect that informs the gathering and telling of stories by practitioners challenges new participants and audiences to recognize structural and humanitarian injustices in the contexts within which they work and live.

Specifically, this article will explore the strategies used to make and produce Seven, a multi-authored piece initiated in the USA by playwright Carol K. Mack that interweaves testimonies from seven activist women from around the world. In addition, it will address a series of Asylum Monologues produced by London-based, UK company ice&fire, which tell the life stories of individuals who have been through the UK’s asylum system. Looking at the processes whereby practitioners and producers nurture recognition of marginalized people, I argue that their attempts to speak to and with others—rather than for, about or over them—enact and model a humanitarian sense of understanding of and responsibility to others, often within contexts where structural injustices are evident. Their efforts help to establish a public sphere of the kind envisaged by philosopher Hannah Arendt, by making the voices of the silenced and stigmatized present. As Arendt writes in The Human Condition (1958), it is through “storytelling” that otherwise privatized and intimate aspects of life are given a sense of reality by bringing them into the realm of what is “seen and heard” by others.4 I argue that the establishment of such realities through the performance of life stories calls for an adjustment to the individual and collective responsibilities of those who perform and hear them.5 In addition, these testimonies encourage a practice of reflexive self-recognition among people and institutions who have the power to agitate for and ultimately to grant rights and recognition to individuals, as well as to work towards cultural change motivated by the desire to alleviate the oppression of vulnerable peoples.

The Stories of Seven and Asylum Monologues

Seven is composed of interwoven first person accounts of the lives and works to further human rights of seven women in Nigeria, Cambodia, Guatemala, Northern Ireland, Afghanistan, Russia, and Pakistan. The play originated in 2007, when playwright Carol K. Mack attended a meeting of Vital Voices Global Partnership (VVGP), a US-based NGO that advances “women’s economic, political and social status around the world.”6 The event incited Mack to contact six other US-based female playwrights who formed the female collective, Many Shining Lights. To make Seven, each writer interviewed a woman active in working for social change around the world who was recommended and sponsored by VVGP.7 With the support of the NGO, Seven premiered in 2008 at the 92nd Street Y Cultural Institution and Community Center in New York. It has since been performed over 150 times in English and in twenty-eight translations across the globe in venues that include the European Union; the Serbian, Ukrainian, and Swedish parliaments; and in many grass root contexts in Europe, South America, Africa, and South Asia.8 Of these, many productions have been undertaken by Hedda Produktion AB, a Swedish company formed by Mack’s longstanding contact Hedda Krausz Sjögren, whose methods frequently combine documentary theatre and advocacy. When produced by Hedda Produktion with the permission of the collective, Seven is presented as Seven on Tour, and is performed as a pared-down rehearsed reading which deploys non-naturalistic casting.

Seven presents the lives and work of seven women who are all, in different ways and in different contexts, actively engaged with and on behalf of other women, to improve access to healthcare, medicine, or workers’ rights, or to help find refuges from violence and trafficking. The life-story for example of Afghan doctor Farida Azizi, which inspired the production, relates how she smuggled vital medicine to housebound women under the Taliban regime. Using the testimonial form that Paul Rae argues privileges “a liberal model of the self-contained subject” as part of its rights-claiming practice, the combination of seven speakers, each with an equally valid story to tell, nevertheless implies a pluralistic and polyphonous outlook based on a bedrock of female solidarity.9 Utilizing an essential staple of feminist performance, an opening sequence in which each woman steps forward to give her name and nationality, “Hafsat Abiola, Nigeria…” and so on, the play immediately establishes a sense of the equal validity of each self-identifying speaker and her right to recognition in the eyes of witnesses assembled.10 Woven together through their common themes, the monologues perform a balancing act between individual agency and collective responsibility and action. Empowering practices of self-narration are combined with passages of consciousness-raising, which draw attention to cultural inequalities and the subordination of women: “Some people are high up and some are inferior,” comments Mukhtar Mai, an illiterate Pakistani villager whose testimony recounts how tribal elders ordered her gang rape. Mai points to the effect of this cultural injustice on “every girl” in her village who “walks in terror of what happened to me.”11 Northern Irish activist Inez McCormack’s testimony about working with women cleaners recalls her realization that people at “the powerless end…the invisible” can be part of a change that comes from “how they see themselves.”12 A sense of agency fueled by a positive self-conception is coupled with calls for an end to exploitative practices, and a calling to account for the gendered structures of male oppression. The testimony of Russian domestic violence worker Marina Pisklakova-Parker tells us that it is necessary not only to rescue or teach drowning kids to swim but to see who is throwing them into the water.13 In an act of solidarity, the whole cast joins with her in reciting sixteenth century household rules that enforce the patriarchal order: “A man should punish his wife to make her more obedient.”14

In telling these life stories, Seven avoids the connotations of passivity that have been associated with female victimology in favor of the active, self-motivated approach of the women activists.15 These are not “victim monologues,” but testimonies of female determination, strength, agency, and committed activity, often in the face of great personal danger. In presenting these women’s bravery and commitment, the stories expand the boundaries of what heroism is allowed to be, as well as appearing to reverse any sense in which the subaltern female might be “rescued” through the interventions of privilege. In Seven, women appear to rescue themselves and each other, each one experiencing a moment of epiphany which leads her to speak out against inequality and to help others fight it too. At the same time, there is an implicit appeal to the audience in the dramaturgy of the interwoven stories. As with Anna Deveare Smith’s Twilight: Los Angeles 1992, according to Alison Forsythe, a “carefully-arranged and hermeneutically-charged juxtaposition of testimonies” occurs.16 An account of the gang rape of Mai, for example, is merged with that of the more privileged Hafsat Abiola, from Nigeria, who receives the dreadful news of her mother’s death while Hafsat is studying at Harvard.17 Such moving but unsettling moments pass without overt comment, leaving the audience to witness the “gap” between the similarities and important differences in the two women’s fortunes. The play ends on the sound-effect of a phone that each woman goes to answer, and the comment from Cambodian activist Mu Sochua, that you have to keep working “until people who do not have a voice, do,” signaling the women’s ongoing commitment.18 Seven, in many ways, is an inspiration to women and to men—a breathing in of animating air that will incite further venture by its witnesses. Its stories also collectively compose a narrative model, as I explore further below, that suggests a positive and industrious trajectory of female activity.

As with the producers of Seven, the London-based theatre company ice&fire uses the testimonial form to tell what it calls “human rights stories.”19 Originally formed around Sonje Linden’s play I Have Before Me a Remarkable Document Given to Me by a Young Lady From Rwanda (2003), the company has produced a range of projects that support the creativity of and public awareness about groups such as asylum seekers. It also runs Actors for Human Rights, founded in 2006 as a network of more than 700 professional actors from across the UK who volunteer their time and skills. Tailoring its rehearsed readings by drawing from the portfolio of testimonies it has gathered, and ready to “go anywhere at any time,” the network performs Asylum Monologues in response to requests from a range of formal and informal organizations around the UK, such as schools, churches, charities, universities, workplaces, and statutory bodies. The company often collaborates with NGOs, including Amnesty International, Save the Children, Refugee Action, and Freedom From Torture, and on occasion has been asked to work with UK government departments. I have attended two versions of these readings, at Kingston Quaker Centre (2015), and at an event held to commemorate the death of Professor Lisa Jardine at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). I will also refer to a version of Asylum Monologues held at the UK Home Office in Leeds (2010).

While the narrative of women’s survival and enterprise articulated and shaped by Seven can be seen as a strand in a complex weft of competing discourses that effectively seek to “write” women’s lives, ice&fire’s monologues can be understood to intervene into a fraught narrative field—recently intensified by the so-called “migrant crisis” caused by mass migration to Europe from the Middle East and Africa. Conflicting views expressed assertively by politicians and journalists range from hostile characterizations of migrant peoples as scroungers, criminals, and terrorists, to the obverse but more supportive views of immigrants as upstanding citizens who make great economic and cultural contributions to the UK. In this febrile climate, what Janelle Reinelt calls the “promise” of documentary is certainly alluring.20 With their origins in the life experiences of suffering and displaced individuals, ice&fire’s testimonies offer not only the “absent but acknowledged reality” of documentary forms, but also seem to satisfy a desire for a more profound, human, and intimate sense of the “truth” of migrants’ lives. Politically, the performances of the testimonies align themselves with a humanitarian ethos and borderless global citizenship that attempts to counter the principles of territorial sovereignty. In performance, as I will argue below, they work within the practice and spirit of a worldly ethic of care propounded by Ella Myers that is infused by Arendt’s notion of amor mundi, in which collaborative and democratic action can align around a shared recognition of reality and understanding of issues and goals.21 Further, their telling affords and unlocks a “temporary sociality” through the phenomenological aspects of storytelling.22

At the Kingston Quaker Centre, to an audience largely composed of local volunteers, three actors told the stories of three asylum-seeking activists: Congolese teacher Willy, Cameroonian opposition party member Mary, and the well-educated Ugandan local councilor, Marjorie. At QMUL, Marjorie’s story was joined by two others: that of fourteen-year-old Lillian who was sex-trafficked from West Africa to the UK, and of Darfuri boy Adam, who fled to Europe after his parents were killed by the Janjaweed.23 In the early parts of the testimonies, physical threats were emphasized, the speakers testifying to appalling treatment such as beatings and brutal gang rape. Rather than a moment of epiphany however as in Seven, and an ensuing capacity to self-help and help others, no redemptive turning point emerges from a moment of abuse. Rather, the asylum seekers’ personal stories are about their struggles to come to terms with the lack of humane and legal recognition offered by the British authorities. As the testimonies unfolded, audience members learned of a country where “the system is killing people mentally,” where mothers with children are traumatized by dawn raids, where detention center Yarl’s Wood is a “terrible” place in which people try to “kill themselves,” and where a stick-thin new mother is discharged from hospital crying and lonely.24 “This is England,” says one of the actors, in a single and sobering line that challenges notions of Britain as a civilized and civilizing place.25 Instead, Asylum Monologues establishes a narrative of England (and the UK more generally) as a place where ordinary and/or aspirational decent people are denied not only recognition through the asylum system, but also the capacity for economic and personal agency. At the end of the testimonies there is a continuing sense of appeal, not for money or benefits, but for “protection” and “safety.” Having “lost hope,” Willy is left in the “limbo” of “a diplomatic form of torture.”26 He effectively lacks a legal status that will enable him to live as a human being, let alone contribute economically and culturally as what might be termed a laborer-citizen. These testimonies require an act of self-recognition that reverses anti-asylum discourse, and exposes the UK’s official and legal structures of recognition as morally wanting.

Globalizing Contexts

In negotiating their respective but related discursive fields, the testimonies of both Asylum Monologues and Seven intervene into wide ranging and complex geopolitical contexts. At pains to avoid running the risk identified by Gayatri Spivak of reducing subaltern women to the status of a “pious item” on a “global laundry list” Seven takes care to present women as agents.27 In so doing however it seems complicit with a narrative that conflates economic potential with moral worth (a tendency also of the narrative that supports migrants on the basis of their economic contribution).

In the online framing of the stories of women by VVGP, including those who were interviewed for Seven, the conflation of a narrative of female agency in which the quality of “leadership” is prevalent with the recognition of entrepreneurial and economic activity is especially evident. The VVGP website describes itself as the “preeminent non-governmental organization that identifies, trains and empowers emerging women leaders and social entrepreneurs around the world.” Founded by Hilary Clinton “to promote the advancement of women as a US foreign policy goal,” its mission includes being at the “forefront” of coalitions that combat human trafficking and violence against women, and to “equip women with management, business development, marketing, and communications skills.”28 In the presentation of over a hundred women “leaders” on its website, the framing of their life stories by VVGP fades into the highly regularized kinds of presentation and packaging performed by and on behalf of individuals in capitalist labor markets. Clicking on one of the “Featured Voices” links leads to Reyna from Venezuela, pictured in dynamic mode, speaking at a meeting. The caption reads, “Reyna McPeck always wanted to be an entrepreneur,” and a few paragraphs of text tell us how after having six children “her entrepreneurial spirit led her back to school.”29 Another woman, Manal Zraiq, is quoted, “I like to work 24 hours a day. Otherwise I get bored. I don’t have slack time.”30 Here perhaps, the website labors on behalf of cultural powers that recognize people’s qualities not according to a status that is perceived to be human, but according to economic utility. On every profile page, the women’s achievements and successes are catalogued, implying that recognition is conferred through the labors of self-actualization, and the women’s capacity for tireless activity. This framing of the stories by VVGP thus comes uncomfortably close to perpetuating a globalized female version of homo economicus as defined by philosopher Michel Foucault, playing into a form of “soft” power in line with the neoliberal interests of the USA and other Western powers. Following this thinking, in the practice of female “leadership” women are encouraged to conform to the culture critiqued by political scientist Wendy Brown, where “maximum individual endeavor and interest” is instituted as a practice of governance.31

Some of the contexts in which Seven has been performed live also suggest negotiations between social and economic structures which emphasize rewards and awards rather than the rights–based system of recognition advocated by humanitarian discourses. When interviewed for a Vital Voices trailer at the opening of the performance directed by Julie Taymor with “Meryl Streep and an all-star cast” at the Hudson Theatre on Broadway, McCormack remarked that she had lived in “narrow,” “hostile,” and “very unpopular” spaces, but that she “never dreamt that she would end up immortalized in a New York play.”32 Her comments suggest that the attention and structures that consolidate the status of privileged individuals in the media-driven entertainment industry might overwhelm the awareness of the feminist and humanitarian activities that the play seeks to raise. Also troubling is the potential for the appropriation of the voices and labor of the female activists to the strategies of the philanthropic activities of large corporations and powerful individuals. The DVF Awards, inaugurated at the 2010 Women in the World Summit, not only grant $50,000 to recipients to further their work, but confirm the virtue and position of fashion impresario and VVGP board member, Diane von Furstenberg. As Kelly Oliver cautions, pointing to the flaws in the Hegelian master-slave model of recognition, the practice of conferring recognition on others by the dominant group “merely repeats the dynamic of hierarchies, privilege, and domination.”33 The point is well illustrated by Abiola’s claim that Seven is an endorsement by “authorized and famous playwrights” from “the most powerful and wealthiest country in the world” that “gives new credibility to our voices…to our identity.”34 This seems a long way from the sense of dialogue and collaboration that lies behind the ethos and making of the play, and which the many women—powerful or otherwise—who have been involved in the making of many of its productions have been at pains to stress.

Negotiating Responsibilities Through Practice

Having acknowledged that the framing and staging of these testimonies can reveal broad material pressures of unequal and disciplinary global and economic structures, I want to return now to the humanitarian and strategic impulses that lie behind their constitution in the immediate contexts of their making and their live performances. As in Seven, and in common with other verbatim and testimonial pieces produced from interviews, Asylum Monologues uses thematic patterning and narrative crafting to shape the material into a whole that is satisfying aesthetically, and which also serves to mobilize the humanitarian impulses of audience members. These pragmatic aims necessitate selective editing of the material. According to current leader of Actors for Human Rights, Charlotte George, on one occasion her fears that the inclusion of comments made by an interviewee could be deemed to be “racist” led her to omit them.35 It is, of course, possible to see such selectivity as a compromise of the authenticity of the original material and an intervention too far into the “reality” that the testimony conveys. Yet the careful diplomacy exercised in such cases might also be considered as part of the responsibility taken on by practitioners who must negotiate between a sense of respect for their interviewees, and the presumed needs of audience members.36 In general, the degree to which the actual words of an interviewee are used is balanced by a politically meaningful determination to treat and represent others with humanity and trust. In some respects this is similar to the flawed but perhaps honorable aspirations of ethnographic research. The approach described by Paula Cizmar, who interviewed Pisklakova-Parker for Seven, for example, seems to coincide with the aim to achieve what Spivak calls the “intimate inhabitation” of the life of another.37 Cizmar’s multiple, thorough, and longitudinal interviews, which were conducted in English in person, by email, and by telephone, aimed to gain a much fuller understanding of her subject’s life in Russia (rather than recycle the already existing “sound bite” discourse in the press surrounding the Russian woman’s activist project).38 Notably, such thorough and respectful processes are appreciated in some policy contexts: Don Flynn of NGO Migrants’ Rights Network for example emphasizes the importance of “substantial life stories” to the development of effective policies.39

With ice&fire, interviews will last several hours, and will aim to engage with the interviewee as a “person as a whole” rather than, for example, “a person who has been trafficked.”40 Contact will often be maintained with interviewees over several years, a span of time that can reflect the wait that asylum seekers experience as part of the application and appeals process. During this time, as I was told by Christine Bacon, current Artistic Director of ice&fire, interviewees report feeling like “they are nobody, that they don’t exist really.”41 Her words echo those of Mary in Asylum Monologues, whose “story” of the dangers of staying in Cameroon was not believed by the UK authorities.42 In contrast, the ice&fire interview process implements an ethical practice of trust that appears to be absent in the treatment that asylum seekers report receiving, and which research identifies as “hostile” and “interrogatory.”43 These interviews are not only according to Bacon “cathartic” for the interviewees, but are themselves human acts of recognition. Unlike Seven, where the testimonies name and recognize women who are active in public life, ice&fire interviewees, still often undergoing the protracted processes of asylum application, often have their names changed to preserve anonymity (although some who have spoken out before will choose to be named). The giving and performance of their testimonies by these legally and emotionally vulnerable people is not a celebration of individual achievement, but an intervention into a context in which the audibility of marginalized and abject voices is heavily policed and in which the denial of recognition is an inhumane and institutionalized practice.

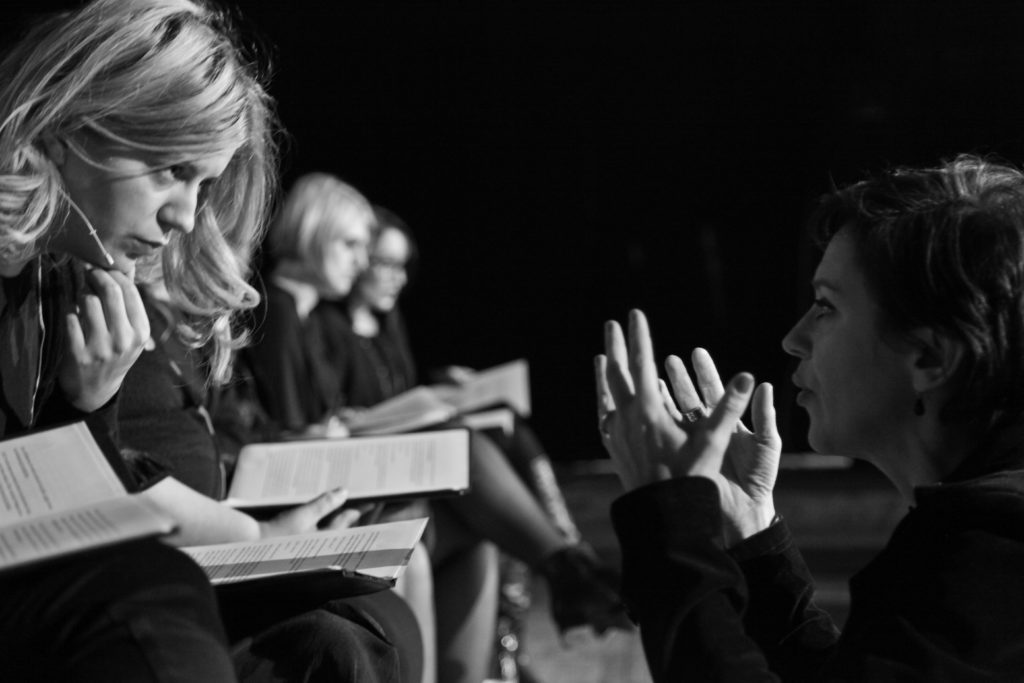

In the performance of these pieces too, there is a political commitment on behalf of performers and audiences. In discussion, Bacon told me that in her necessarily brief preparations of actors for reading the scripts, she asks them to “sink into the emotion of that moment.” This stops short of recommending the Stanislavskian processes that might encourage actors to overlay the script with their own emotional and imaginative interpretation, a tendency that tends to be strongly disavowed by actors rehearsing documentary material.44 Indeed, Bacon is concerned that actors “honor” the whole person from whom the transcripts emerge.45 Her instruction challenges actors’ reluctance to intervene in the aura of authenticity that is attached to the actual words of another living person, and provokes a deeper sense of the “responsibility towards their subject” that Mary Luckhurst observes is already heightened when actors play real people.46 Using Bacon’s process of “emotional sinking,” a humanitarian act of recognition is performed in which actors speak empathetically with rather than over interviewees as they mediate their words to audiences. When performing, Actors for Human Rights member Helen Clapp explains that she aims to act as a “conduit,” discerning and conveying the “emotional footprint” of the original speaker through the transcript.47 Clapp’s commitment was evident on the two occasions I saw her dexterously wielding the skills of her acting training to bring clarity and structure to the transcript she performed. With Marjorie’s testimony in her hands, alluding to its origin in the life experience of another human being, Clapp performed not only the words of the asylum seeker, but a rhythmic act of embodiment that might be called “transhuman.” Differences such as race, age, background mattered less than the act of recognition of another individual, her words, and her story.

This performative form of recognition can reveal more about the values and labor of the performer and her audience than the original speaker. In this case, the latter is mediated and constituted partly by taking her words from an intimate and personal conversation and making them public—an act which according to verbatim practitioner Robin Soans “confers a responsibility on an audience” and accounts for the “increased intensity” of their listening.48 During these live performances, a shared sense of connectedness is generated; audience members are brought together by a sedentary version of the “affective solidarity” that is evident according to Elaine Aston at the locally performed intersectional dance project One Billion Rising.49 Although very differently involved from the latter’s flash-mob cohort, I would argue that performers and audience members who gather at both ice&fire events and at the readings of Seven produced by Hedda Produktion, are brought together by the kind of “goal-directed” purpose identified by Aston. As she claims of participants in One Billion Rising, they share an appetite for a “story” that articulates counter-hegemonic, humanitarian and/or feminist values. To return to Arendt’s terminology, the testimonial forms I discuss here, expressed and grounded in individual, intimate, and painful realities brought into the public realm by means of “artistic transposition,” counter anti-humanitarian or neoliberal discourses that would cancel supplicants’ claims to support or asylum.50 At the readings, an enhanced sense of connectedness and responsibility is harnessed, as proceedings are carefully orchestrated to flow into a discussion session with performers and audience members. In these sessions, appropriate action is identified (relevant to the resources and interests of the local communities), and a further commitment encouraged to a public sphere governed by mutual respect and active engagement. Here the “social processes” that to Iris Marion Young make possible “a model of responsibility based on social connection” are activated through public activity and dialogue that commits to local action and humanitarian values.51

Accountabilities and Action in Professional and Public Spheres

The story-telling tactics deployed by the producers of Seven and Asylum Monologues play important roles in opening dialogue that leads to the recognition of humanitarian issues and activates changes to legal and cultural structures and practices. With Hedda Produktion, which first produced Seven in Sweden in 2008 under director-producer Krausz Sjögren, Seven on Tour has been performed in diverse locations, including Bosnia-Herzegovina, Egypt, the Ukraine, and Bangladesh. In these iterations, the “brand” developed around the project is a valuable asset, bolstering the chances of forming and strengthening the investment of a local community of stakeholders, including universities, government bodies, businesses, and charities. In these contexts, the choice of readers for the testimonies is not concerned primarily with notions of authenticity in casting, but with the leveraging of potential partners who can activate change. Workshops that precede and follow the performances have time only to make use of simple performance strategies, but also aim to make energizing and productive interventions into participants’ working practices.52 According to Cecilia Wikström, of the Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, who was one of seven female MEPs who performed Seven at the European Parliament in 2010, “being politicians, we are always on the surface of everything.…To come together and to focus on a literary text has never been done before in this House.”53 Her comments suggest a collaborative and creative disruption to the normal round of emails and meetings around a project that engages participants affectively and corporeally with the life and experience of another human being. As with the “community of interest” imagined and formed by Bacon’s ice&fire around asylum seekers, Hedda’s tactics form a constellation of parties invested in the recognition of need and of human potential, rather than a hierarchal structure that offers to rescue or reward the vulnerable individual.54

In addition to the tactic of infiltrating structures in which individuals can effect change, performances of both Seven and Asylum Monologues also contribute to a sense of a democratic and egalitarian sphere of public responsibility. At the event I attended at University College London (UCL), Seven was read by the University’s Provost and six of its Vice-Provosts as part of a series of free-of-charge events to mark International Women’s Day in 2015. After the reading of the testimonies of abuse and activism by the seven powerful male academics, young female students in the audience challenged them on the lack of female representation at the highest levels of the university, and on the prevalence of sexual abuse among students. One academic admitted that he would have to step down in order to make way for female colleagues.55 On another striking occasion in 2014, the play was performed by seven NATO generals in military uniform at the Alliance auditorium at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe. For me, watching the footage of this event is a reminder of the geopolitical, military, and territorial contexts that might otherwise be downplayed by the narrative of individual achievement that is emphasized in Seven’s testimonies.56 In my interview with Krausz Sjögren she reminded me of the ritualistic function of theatre, gathering people to discuss ethical issues and contributing to democratic accountability. It is a sentiment echoed by Annecy Hayes, Associate Artist at ice&fire: theatre “is able to move people” and “to hold people to account in one room.”57 The tactic of casting powerful individuals to read “real” life stories in front of a group of witnesses both imbues these performers with a sense of responsibility, and creates an expectation that they will take action. Further, the question and answer sessions enable audience members to go beyond the passive and limited “gallery” status they are often granted in the public sphere to become an active and participatory body of individuals who insist on the accountability of leadership.58 In many cases, such as in its campaign for lamps at bus stations so that female students can study longer in the library on Bangledesh university campuses, or in its call for policy change on gender-based violence in Ukraine and Serbia, the sustained involvement of Hedda Produktion aims to push through actual practical and cultural change that will improve women’s lives.59

Equally concerned to make change happen, ice&fire practitioners recognize that they are often invited to perform Asylum Monologues to already aware and active individuals and audiences. On certain occasions, they are able to reach and challenge people whose work administers the recognition on which the all-important legal status of asylum seekers depends. At a performance in the UK Home Office in 2010, ice&fire confronted staff with accounts of beheadings, gang rapes, and other horrific abuses suffered by asylum seekers in their home countries, as well as a testimony from Louise Perrett, an ex-Border Agency employee who spoke to the press and to a parliamentary committee.60 In this piece, the influence of wider discourses and narratives upon the treatment of asylum seekers is clear. Louise’s testimony describes how staff are trained to believe that asylum seekers are “potentially dangerous,” that “these people are probably lying to you,” and that their “responsibility” is to catch the “bogus asylum seeker.”61 According to Bacon, the forty-five minutes of discussion scheduled to follow the performance turned into ninety.62

Unsurprisingly, when the UK Foreign Office itself commissioned ice&fire to produce a script for the 2015 Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict in London it was reluctant to endorse the inclusion of a testimony from a Sri Lankan national whose application for asylum had been refused and who was held at an immigration detention center at the time of the interview. As I have argued, these monologues testify to a version of the UK as a brutalizing and hostile state, in contrast to which asylum seekers’ humanitarian standards offer desirable norms of conduct. At the same time, ice&fire monologues suggest a narrative that “saves” the UK by instantiating a humanitarian activism through which all citizens can act on the recognition of human need. A ticket collector Mary meets on a train makes calls to her colleagues to help her on her journey. When she arrives in Glasgow there is a network of people, including Margaret and Phil from the Glasgow Campaign to Welcome Refugees and Asylum Seekers, who help her evade Immigration. Another ice&fire piece, Asylum Dialogues, is specifically about surprising encounters between British citizens and asylum seekers that elicited many acts of generosity and solidarity.

As I have suggested, combined and entwined, the testimonies gathered and scripted both by ice&fire practitioners and by the makers of Seven aim to impeach dominant structures and institutions of power, suggesting alternative humanitarian counter narratives and networks. Although the stories that emerge from their interviews can sometimes enforce dominant disciplinary discourses, their methods of making suggest a dialogic and reflexive storytelling, grounded in processes that engage with and aim to honor the “whole” person whose life story is constructed. Performances help to create a public sphere that practices responsibility and encourages accountability by attending to the presence of others, and which actively infuses audiences through listening and dialogue with a sense of shared commitment to humanitarian values and actions.

In my research I have been conscious of my own efforts to balance a sense of responsibility to the practitioners who have generously supported me in writing this article, a necessary selection process that could itself lead to the misrepresentation and misrecognition of their work, my own institutionalized position of academic privilege, and the demands of scholarly practice. I offer this article, however, in a spirit of critical activism with which scholarship might usefully play a role in interrogating and rebalancing issues of local and global injustice, and which I hope contributes to an active public realm committed to the audibility of its citizens and a shared sense of responsibility to issues of global injustice.

Notes

- Charles Taylor, “The Politics of Recognition,” in Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition, ed. Amy Gutmann (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 25. ↩

- In the UK, the term “verbatim” is often preferred to “documentary” to describe a style of theatre where the exact words of an interviewed subject are reproduced. Harry Derbyshire and Loveday Hodson, “Performing Injustice: Human Rights and Verbatim Theatre,” Law and Humanities 2 (2008): 198. ↩

- David Michael Boje and Grace Ann Rosile, “Storytelling,” in Encyclopedia of Case Study Research, Volume II, ed. Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos and Elden Wiebe (Los Angeles: Sage, 2010), 899. ↩

- Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998 {1958}), 50. ↩

- See Annabel Herzog, “Hannah Arendt’s Concept of Responsibility,” Studies in Social and Political Thought 10 (2004): 39. ↩

- “History,” Vital Voices, accessed December 19, 2015, http://www.vitalvoices.org/about-us/history. ↩

- US playwrights Paula Cizmar, Catherine Filloux, Gail Kriegel, Carol K. Mack, Ruth Margraff, Anna Deavere Smith, and Susan Yankowitz interviewed Marina Pisklakova-Parker (Russia), Mu Sochua (Cambodia), Anabella de Leon (Guatemala), Inez McCormack (Northern Ireland), Farida Azizi (Afghanistan), Hafsat Abiola (Nigeria), and Mukhtar Mai (Pakistan), respectively. ↩

- See “The Countries of Seven on Tour,” Seven Women, accessed January 16, 2016, http://www.sevenwomen.se/the-project/countries. Information updated by Hedda Krausz Sjögren, e-mail to author, February 17, 2016. ↩

- Paul Rae, Theatre & Human Rights (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 16-18. ↩

- See Deirdre Heddon, Autobiography and Performance: Performing Selves (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 25; Paula Cizmar et al., Seven (New York: Dramatists’ Play Service, Inc., 2009), 13. ↩

- Cizmar et al., Seven, 21-24. ↩

- Ibid., 32. ↩

- Ibid., 37. ↩

- Ibid., 27. ↩

- See Rosemary Barberet, “Feminist Victimology,” in Encyclopedia of Victimology and Crime Prevention, Volume 1, eds. Bonnie S. Fisher and Steven P. Lab (Los Angeles: Sage, 2010), 406-408. ↩

- Alison Forsythe, “Performing Trauma: Race Riots and Beyond the Work of Anna Deavere Smith,” in Get Real: Documentary Theatre Past and Present, ed. Alison Forsyth and Chris Megson (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 142. ↩

- Cizmar et al., Seven, 28. ↩

- Ibid., 38. ↩

- “About Us,” ice&fire, accessed January 16, 2016, http://iceandfire.co.uk/project/actors-for-human-rights. ↩

- Janelle Reinelt, “The Promise of Documentary,” in Get real: Documentary Theatre Past and Present, eds. Alison Forsyth and Chris Megson, Performance Interventions (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 10. ↩

- See Ella Myers, Worldly Ethics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 87-88. ↩

- Reinelt, “Promise,” 11. ↩

- ice&fire, Asylum Monologues (performance script for Queen Mary University London, November 17, 2015). ↩

- ice&fire, Asylum Monologues (performance script for Kingston Quaker Centre, June 15, 2015). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (New York: Harvester/Wheatsheaf, 1994), 104. ↩

- “About Us,” Vital Voices, accessed December 23, 2015, http://www.vitalvoices.org/about-us/history and http://www.vitalvoices.org/about-us/about. ↩

- “Reyna McPeck,” Vital Voices, accessed January 18, 2016, http://stories.vitalvoices.org/#/detail/reyna_mcpeck. ↩

- “Manal Zraiq,” Vital Voices, accessed January 18, 2016, http://www.vitalvoices.org/vital-voices-women/featured-voices/manal-yaish-zraiq-0. ↩

- Wendy Brown, “Wendy Brown: Homo Economicus,” Interview with Sam Seder, accessed January 18, 2016, http://www.artandeducation.net/videos/wendy-brown-homo-economicus/. ↩

- “Seven–A Documentary Play (Trailer),” March 9, 2008, accessed January 22, 2016, http://www.vitalvoices.org/media/seven-documentary-play-trailer. ↩

- Kelly Oliver, Witnessing: Beyond Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), 9. ↩

- “Seven–A Documentary Play (Trailer).” ↩

- Charlotte George, “Workshop 2: ice&fire” (conference workshop, Gendered Citizenship: Manifestations and Performance Conference, University of Warwick, January 6, 2016. ↩

- See, for example, Yaël Farber’s account of her process in Theatre as Witness (London: Oberon, 2008), 19-28. ↩

- See D. Soyini Madison, Acts of Activism: Human Rights as Radical Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 24–25. ↩

- Paula Cizmar, e-mail message to author, November 24, 2015. ↩

- Dan Flynn (lecture, Lost Journeys, Queen Mary University of London, November 17, 2015). Also see Hugo Slim and Paul Thompson, Listening for a Change: Oral Testimony and Development (London: Panos, 1993), 7. ↩

- Charlotte George, Gendered Citizenship. ↩

- Christine Bacon, interview with author, Park Theatre London, December 11, 2015. ↩

- ice&fire, Asylum Monologues, Kingston. ↩

- Jo Wilding and Marie-Bénédicte Dembour, Whose Best Interest?: Exploring Unaccompanied Minors’ Rights Through the Lens of Migration and Asylum (University of Brighton, 2015), 2. ↩

- See Tom Cantrell, Acting in Documentary Theatre (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 52. ↩

- Bacon, interview. ↩

- Mary Luckhurst, Playing for Real: Actors on Playing Real People, eds. Tom Cantrell and Mary Luckhurst (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 20. ↩

- Helen Clapp, “Workshop 2: ice&fire” (conference paper, Gendered Citizenship: Manifestations and Performance Conference, University of Warwick, January 6, 2016. ↩

- Robin Soans, in Verbatim Verbatim: Contemporary Documentary Theatre, ed. by Will Hammond and Dan Steward (London: Oberon, 2008), 24. ↩

- Elaine Aston, “Agitating for Change: Theatre and a Feminist ‘Network of Resistance,’” Theatre Research International 41, no. 1 (2016): 12-14. ↩

- Arendt, Human Condition, 50. ↩

- Iris Marion Young, “Responsibility and Global Justice: A Social Connection Model,” Social Philosophy and Policy 23, no. 1 (2006): 102. ↩

- Hedda Krausz Sjögren, interview with author, Skype, November 26, 2015. ↩

- Cecilia Wikström, “Women’s Rights Take Centre Stage,” December 9, 2010, accessed January 22, 2016, http://www.europarltv.europa.eu/en/player.aspx?pid=6747ef37-fdb8-4756-882f-9e470117831c. ↩

- Christine Bacon, “ice&fire Theatre,” accessed January 22, 2016, http://iceandfire.co.uk/about-us. ↩

- Seven, performance, University College London, March 2, 2015. ↩

- “Seven the Play at SHAPE,” Seven the Play, May 7, 2015, accessed January 22, 2016, http://seventheplay.com/about-seven/. ↩

- Annecy Hayes, ‘ice&fire Theatre.’ accessed January 22, 2016, http://iceandfire.co.uk/about-us. ↩

- See Sabine Lang, NGOs, Civil Society, and the Public Sphere (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 9. ↩

- Anna Leach, “Magnificent Seven,” The Guardian, January 25, 2016, accessed March 11, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jan/25/seven-global-drama-womens-rights-violence-rape-trafficking-bangladesh. ↩

- Hugh Muir and Diane Taylor, “Border Staff Humiliate and Trick Asylum Seekers–Whistleblower,” The Guardian, February 2, 2010, accessed February 12, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/feb/02/border-staff-asylum-seekers-whistleblower. ↩

- ice&fire, Asylum Monologues (performance script for Home Office Leeds, November 2010). ↩

- Bacon, interview. ↩