“I needn’t say anything. Merely show. I shall purloin no valuables, appropriate no ingenious formulations. But the rags, the refuse—these I will not inventory but allow, in the only way possible, to come into their own: by making use of them.”

—Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

I

Although not yet a household name, Walter Benjamin had been elevated to the status of iconic figure within the American academy by the end of the twentieth century. Through his analysis of material culture, his engagement with the urban landscape, and his excavation of those revealing contradictions that find expression throughout the capitalist superstructure, Benjamin developed analytic tools that were of particular relevance to scholars in cultural studies. In her influential 1992 essay on the Passagenwerk, Angela McRobbie solidified this canonical status by casting Benjamin as an important precursor to (and ongoing resource for those working within) the field.1 But while Benjamin is now an established and canonical reference point among cultural studies scholars, and while a considerable secondary literature has emerged around his work, efforts to clarify and build upon his insights by operationalizing them have remained relatively rare.2

I view this shortcoming as being significant for two reasons. First, and from a political standpoint, the moment of danger in which we now find ourselves (a moment characterized by fascist resurgence and the collapse of liberal-democratic norms) demands not only that we grasp our condition analytically; it also enjoins us to act so that the catastrophic outcomes presaged by our present do not come to pass.3 Having confronted a similar moment of danger during his own lifetime, Benjamin developed intellectual tools for engaging in this work—and cultural studies scholars could play an important role in fulfilling the theoretical and practical tasks he bequeaths us. Second, and from the perspective of analysis, I maintain that it is solely through its operationalization that Benjamin’s intellectual project can truly be understood.4

In what follows, I substantiate these claims by providing an episodic sketch of Benjamin’s lifelong intellectual project to reveal the coherent methodology that might be derived from it. From there, I demonstrate by way of example how this method might be operationalized today. In keeping with Benjamin’s insistence that the materialist presentation of history should “purloin no valuables” nor resort to any “ingenious formulations,” I have restricted myself to the consideration of details that for many readers will already be familiar. Nevertheless, when intellectual biography is approached less as an itinerary of influences than as a procedure for contemplating the unfolding implications of a thinker’s guiding impulses, it becomes clear that (plausible distinctions between intellectual phases notwithstanding) even these mundane details can be prodded to reveal a coherent methodology that might be operationalized once understood.

II

According to Benjamin biographer Pierre Missac, already by 1984, “a general critical bibliography” comprised of secondary sources on Benjamin contained “no less than 180 pages, despite lacunae that are certainly excusable.”5 To get a true sense of Benjamin’s new cultural ubiquity, however, one must turn (as Benjamin himself might have) to a more anecdotal but undeniably illuminating realm.6 Here, one discovers that, by 2011, the fashionable practice of name-dropping Benjamin in scholarly works had become widespread enough to be made the subject of literary satire.

In “Once We Were Swedes,” Canadian author Zsuzsi Gartner mixes a solemn love story with a murder mystery, a college classroom, and impressionistic strolls through Vancouver as the city disintegrates. “It was the year the enterprising homeless constructed . . . tiny huts from purloined election signs,” begins one vignette. Inevitably, “the design world took notice, with the San Francisco-based architectural magazine Dwell running a photo essay with text by Toronto’s latest public intellectual.” Putting the finishing touches on her snapshot, Gartner concludes by recounting how the Dwell author “supplied the requisite Walter Benjamin quote from ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’” before ending with “some McLuhenesque wordplay.”7

Included in Better Living Through Plastic Explosives (a collection shortlisted, along with a work by Michael Ondaatje, for the 2011 Giller Prize), Gartner’s story serves as a useful historical marker. Edgy and acerbic, the references she marshals are nevertheless presumed to be familiar—and the satirical form only works when its target is in a position to be dressed down. But while Gartner’s riposte does much to reveal the scale and character of contemporary engagements with Benjamin’s work, the reasons underlying this development must still be determined. Here, beyond Benjamin’s literary virtuosity, his intellectual seductiveness, and his role in highlighting subject matter that would go on to become the bread and butter of cultural studies, one must acknowledge the sincerity with which Benjamin enlisted his readers as accomplices to—and therefore as active participants in—the act of discovery.

In 1934, Benjamin noted that, even as the newspaper had signaled the deterioration of bourgeois writing, it had nevertheless become a revolutionary medium in the Soviet Union, where practical considerations had abolished the distinction between author and reader.8 Adopting a similar posture in One-Way Street a few years earlier, Benjamin argued that “significant literary work” required “a strict alternation between action and writing.” Consequently, such work needed to “nurture the inconspicuous forms that better fit its influence in active communities than does the pretentious, universal gestures of the book—in leaflets, brochures, articles, and placards.” Indeed, “only this prompt language shows itself actively equal to the moment.”9

Reiterating this insight in a note added to The Arcades Project and sharpening it into a pointed maxim, Benjamin was convinced that—in assembling the material for his study—he “needn’t say anything. Merely show.”10 This showing, I argue, presupposed the active engagement of the reader-viewer, and it pertained not solely to things but to method, not solely to what but to how. The process itself was designed for emulation, and it is this methodological impulse that has continued to make Benjamin’s work so seductive. But while seduction can sensitize us to the value of a methodological approach, it can never be the means by which the methodology is itself conveyed.

Committed as he was to showing rather than saying, Benjamin did not always elaborate the premises guiding his investigations directly. Nevertheless, reviewing his output from the 1915 essay on the “Life of Students” right through to his final testament in the “Theses” of 1940 makes clear that his intellectual project was governed by (and therefore can be made to disclose) an overarching methodological coherence.11 This coherence makes it possible to operationalize and thus to extend the project itself, to emulate Benjamin not through the ornamental deployment of his insights (as frequently happens) but through the very process of thinking and doing. Still, Benjamin’s approach left much room for uncertainty. At one point, Theodor Adorno claimed that it amounted to little more than a “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts,”12 and even Benjamin once conceded that it was better described as “a trick than a method.”13 For those seeking to operationalize Benjamin, the attributes of this trick must be clarified.

III

In the introduction to their Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life, Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings propose that the enormous secondary literature on Benjamin was “notable for its lack of unanimity on any given point.” Nevertheless, they observe, many of the contributions to this literature were united in their tendency to “proceed in a relatively selective manner, composing a thematic order that usually eliminates whole regions of [Benjamin’s] work.” In an effort to correct the “distorted portrait” this approach has yielded, the authors commit to “a more comprehensive treatment by proceeding in a rigorously chronological manner, focusing on the everyday reality out of which Benjamin’s writings emerged.”14 From this perspective, they argue, “the pronounced multiplicity” of Benjamin’s output “does not exclude the possibility of an inner systematic, or of a textual consistency.”15 Here, and “regardless of theme or subject matter,” Eiland and Jennings note that, “from first to last, [Benjamin] was concerned with experience, with historical remembrance, and with art as a privileged medium of both.”16

Like Eiland and Jennings, I endorse efforts to identify the underlying coherence of Benjamin’s project while guarding against the tendency to marshal his insights in a selective fashion. Nevertheless, it should be noted that their commitment to a “rigorously chronological” corrective stands in sharp contrast to Benjamin’s own preferred approach. Indeed, through constant retrospective reevaluation and the reincorporation of prior insights, Benjamin made his own intellectual biography an affront to conventional temporalities. In contrast to the position advanced by Eiland and Jennings, Benjamin cautioned against the desire to write histories “that showed things ‘as they really were,’” since doing so meant succumbing to “the strongest narcotic of the century.”17

By constellating his own work, Benjamin demonstrated that it was possible to transform the character and significance of his earlier observations. Among his notes for the Arcades Project, he wrote, “everything one is thinking at a specific moment of time must at all costs be incorporated into the project at hand. Assume that . . . one’s thoughts, from the very beginning, bear this project within them as their telos.”18 Similarly (and despite the fact that Benjamin’s Trauerspiel study belonged to an earlier metaphysical stage that he had supposedly transcended by the 1930s), he sought to “see the nineteenth century just as positively as [he] tried to see the seventeenth century in the work on Trauerspiel.”19 He went on to add, “The book on the Baroque exposed the seventeenth century to the light of the present day. Here, something analogous must be done for the nineteenth century but with greater distinctness.”20

Given these complex overlaid temporalities, approaching Benjamin as Eiland and Jennings propose cannot help but distort the fundamental source of his project’s intellectual coherence. This coherence owes not to a catalogue of successive influences, nor to the persistence of its content and themes (experience, historical remembrance, art); instead, it arises from a methodological orientation. This method did not emerge fully formed; however, its successive development through each stage of Benjamin’s intellectual journey suggests that it is best understood not in terms of progress but actualization.21 Let’s now consider its development across various moments.

In his dissertation on “The Concept of Criticism in German Romanticism” published in 1920, Benjamin began formalizing a means by which to force objects to reveal their concretely synecdochal status. Recalling the Romantic orientation to criticism, which aimed less at invalidating contributions than at completing them by uncovering the broader reality they encapsulated and reflected, he embarked on a journey that would ultimately lead to profane illumination.22 “The Romantics’ endeavors to reach purity and universality in the use of forms,” he wrote, “rests in the conviction that, by critically setting free the potential and many-sidedness of these forms (by absolutizing the reflection bound up in them), the critic will hit upon their connectedness as moments within the medium.”23

Benjamin’s engagement with Romanticism provided a strong methodological foundation for his subsequent materialism. It’s important to recall, however, that his interest in what we might think of as synecdochal analysis was already well established by 1915 when, in his essay on the life of students, he sought to foreground those moments in which history itself seemed “concentrated in a single focal point, like those that have traditionally been found in . . . utopian images.” Such an approach was indispensible, he thought, since it helped to reveal how “elements of the ultimate condition . . . are deeply rooted in every present in the form of the most endangered, excoriated, and ridiculed ideas and products of the creative mind.” Consequently, “the historical task is to disclose this immanent state of perfection and make it absolute, to make it visible and dominant in the present.”24

Rendered though it was in a breathless metaphysical idiom, the posture that Benjamin assumed when considering the life of students both anticipated and oriented him toward the Romantic conception of reflection with which he would grapple five years later. Finally, with the analytic elaboration of the dialectical image in the work he conducted during the 1930s, his approach began to take on a strong materialist inflection. By 1940, Benjamin was convinced that, as a result of the method he had devised, it was possible to find (not only analytically but practically, not only metaphysically but materially) “in the lifework, the era; and in the era, the entire course of history.”25 For this reason, and at their threshold, analysis and struggle become inseparable. “Only for a redeemed mankind,” he observed, could the past “become citable in all of its moments.”26

If every opportunity (and, a fortiori, everything) was always and at least implicitly present in everything else, then “every second of time” could conceivably become “the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter.”27 All that was required (but this was no small thing) was the ability to acknowledge the animating desire, identify the unresolved means through which it might be fulfilled, and commit to the decision this fulfillment demanded. Only apparently paradoxical, it was through metaphysical and theological invocations of this kind (through forays into the realm of redemption and the absolute) that Benjamin strove to complete the Marxism of his time, which had subordinated its spirit of struggle and sacrifice to a mechanistic conception of progress. These efforts were not always well received, or even understood, by his peers.

IV

In his introduction to Benjamin’s collected works, Adorno admitted that his friend’s philosophy “invited misreading” because it dared the reader to “reduce it to a succession of desultory apercus, governed by the happenstance of mood and light.” Despite this perceived eclecticism, however, he maintained that “every one” of Benjamin’s insights “had its place within an extraordinary unity of philosophical consciousness.”28 Adorno never specified the precise character of the unity to which he referred; however, the propensity toward “misreading” against which he cautioned proved to be real enough. It owed not least to the fact that Benjamin’s desire to show rather than tell left him open to enlistment by rival intellectual camps, where opportunistic partisans would distort his method through the selectivity of their invocations.

Standing prominently on the side of metaphysics and theology, Gershom Scholem felt that Benjamin needed to be rescued from his Marxist readers, his friends, and even from himself. During the 1930s, Scholem even declared that Benjamin’s Marxist allegiances had blunted the latter’s most penetrating insights. He was not alone in this assessment, however, and Adorno-the-Marxist critiqued Benjamin for similar reasons. In a letter dated August 2, 1935, Adorno admonished Benjamin for de-theologizing his conception of the dialectical image in the arcades project exposé he had composed that year.29 Summarizing the problem in a letter dated November 10, 1938, Adorno wrote: “your solidarity with the Institute of Social Research, which pleases no one more than myself, has induced you to pay tributes to Marxism which are not really suited to either Marxism or to yourself.”30

Given the tensions between metaphysical-theological and Marxist interpretations of Benjamin’s work, the confluence between Scholem and Adorno’s assessments here is both surprising and suggestive. Despite their differences, both thinkers struggled to envision how their friend’s apparently divergent postures might be maintained. But while Adorno conceded that Benjamin’s theology might be complementary, if not to Marxism per se, then at least to the aims of the Institute for Social Research, Scholem would countenance no such rapprochement. From his perspective, Benjamin’s thought proceeded along two separate and incompatible tracks. And since no synthesis was possible, only one side of his friend’s “Janus face” could be saved.31 As a result of the “two-track aspect of Benjamin’s thinking, in which mystical intuition and rational thought [were] frequently only seemingly connected by dialectic,” it was obvious to Scholem that Marxism needed to be purged.32

Recoiling from what he took to be the unresolved character of Benjamin’s “Work of Art” essay, Scholem attacked his correspondent’s new “concept of aura,” which seemed to have been de-theologized. Indeed, since Benjamin had used the concept in an “entirely different sense for many years,” Scholem was dismayed to find that a “pseudo-Marxist” iteration had developed in its place. As far as Scholem was concerned, this new conception “constituted, logically speaking, a subreption” that allowed his friend to “sneak metaphysical insights into a framework unsuited to them.” It was thus to his great dismay that “Benjamin emphatically defended his orientation.”

He said that his Marxism was not dogmatic but heuristic and experimental in nature, and that his transposition into Marxist perspectives of the metaphysical and even theological ideas he had developed in the years we spent together was in fact meritorious, because in that sphere they could become more active, at least in our time, than in the sphere originally suited to them.33

Conceived in response to an aggressive interlocutor and beholden to Scholem’s paraphrase, Benjamin’s reply nevertheless suggests that he understood the relationship he had forged between metaphysics and Marxism in terms of reflection—and thus of possible absolution—rather than of rupture or subreption. Earlier metaphysical considerations had not to been abandoned in the move to Marxism; instead, they were given an opportunity to come into their own. In this way (and though he did not state it directly), Benjamin made clear that the method he had devised for absolutizing objects could be applied to epistemological standpoints as well. Forced into constellation with Marxism (its putative antonym), theology discovered the point of sublation for which it had always longed. In a similar fashion, Marxism too was saved from the deformations it suffered at the hands of those who subjected it to a catechistic recitation.

Such a resolution infuriated Scholem. In a letter to Benjamin dated November 1937, he complained that his friend’s essay on the historian and collector Alfred Fuchs had highlighted the limits of his Marxist allegiance in no uncertain terms. “It is to the detriment of your work,” Scholem winced, “that you have cast your insights before dialectical swine. . . .”

What strikes me strongly is this: Marxist insights always remain mired in methodology and never reach the realm of the factual. . . . Where the factual appears, it explodes the limit of the so-called method. . . . I would feel better without it, and I am sadly convinced: you would as well.34

Scholem’s campaign against dialectical swine continued beyond Benjamin’s death in 1940. In opposition to the new generation of militants who began rediscovering Benjamin during the post-war period, Scholem doubled down on his conviction that his friend’s work could only be understood in rarified metaphysical-theological terms. Moreover, he asserted, Benjamin’s true commitments (led astray though once they’d been) were even antithetical to Marxism. By Missac’s account, this position became so extreme that Scholem even took Benjamin’s “Theses” to be an “unqualified retraction of the errors he had committed.”35 By the 1960s, Scholem’s certainty had become absolute. “Nothing remains of historical materialism” in Benjamin’s final essay, he gloated, “except the term itself.”36

V

Scholem’s anti-Marxism led him to produce a doubtful reading of the “Theses” and of Benjamin’s work more generally.37 Nevertheless, his tirade against “dialectical swine” forces us to recall the distorted Marxism of those demagogues who furnished the backdrop against which Benjamin was writing. In his Political Report of the Central Committee to the Sixteenth Congress of 1930, for instance, Stalin confirmed that “the highest development of state power” was in fact the precondition “for the withering away of state-power.” Such a position was contradictory, he conceded, but “this contradiction is bound up with life, and it fully reflects Marx’s dialectics.” Enjoining fratricide to parade about as analysis, Stalin concluded his assessment on the following ominous note: “anyone who fails to understand these dialectics . . . is dead as far as Marxism is concerned.”38

In light of Stalin’s decree, Scholem’s misgivings about Marxism and dialectical reasoning may appear to be well founded. When applied to Benjamin’s texts, however, this same posture becomes wholesale analytic distortion. Along with downplaying Benjamin’s “heuristic and experimental” knack for forging illuminating connections (not only between disparate artifacts but whole schools of thought), Scholem also failed to appreciate the remarkable degree to which his friend had managed to foreground aspects of Marx’s own work that had become obscured by Soviet orthodoxy. Ultimately, Benjamin’s allegiance to Marxism owed neither to self-loathing nor devotion as Scholem and Adorno had respectively maintained. Instead, it arose from his impressive ability to salvage ideas within Marxism itself that had become “endangered, excoriated, and ridiculed” under the shadow cast by Stalinism.39

Rediscovering Marx through Benjamin is therefore highly illuminating. In addition to foregrounding the degree to which—by the beginning of the twentieth century—Marx had been pummeled by his vulgarizers,40 the procedure also reveals the regularity with which Marx himself generated insights that (in retrospect) cannot help but seem quintessentially Benjaminian. Among the many traces of this intriguing co-implication, perhaps the most telling is to be found in the following comments, which Marx conveyed in a letter to Engels dated March 25, 1868: “Human history is like paleontology,” he wrote. “Owing to a certain judicial blindness even the best intelligences absolutely fail to see the things which lie in front of their noses. Later, when the moment has arrived, we are surprised to find traces everywhere of what we failed to see.”

The first reaction against the French Revolution and the period of Enlightenment bound up with it was naturally to see everything as mediaeval and Romantic. . . . The second reaction is to look beyond the Middle Ages into the primitive age of each nation, and that corresponds to the socialist tendency, although these learned men have no idea that the two have any connection. They are therefore surprised to find what is newest in what is oldest—even equalitarians, to a degree which would have made Proudhon shudder.41

Predating Benjamin’s own methodological excursions by more than half a century, this single compressed passage alerts us to the ease with which Marx oriented toward Benjaminian themes like correspondence and the trace, the simultaneity of the old and the new, and the decisive moment in which revelation bursts forth. Admittedly (and when guided by orthodox conceits), this letter may seem atypical when compared to other works in the Marxist canon. Nevertheless, it reiterates insights that can already be detected in The Eighteenth Brumaire of 1852.42 And even if we accept Althusser’s thesis (which I don’t) that Marx can only be understood from the standpoint of an epistemological break dividing his early work (still beholden to German idealism) from his later materialist output,43 we must still contend with the fact that the “paleontology” letter (concerned though it was with problems of perception) was drafted one year after the 1867 publication of Capital, Volume I, Marx’s most revered “mature” text.44

VI

Benjamin’s engagement with absolutizing reflection was tied from the beginning—and as early as his essay on the life of students—to an awareness of the important role that images (whether visual or literary) played in the struggle for redemption. In “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” he proposed that images enabled people to anticipate the future by recalling traces of a mythical past whose promise had yet to be fulfilled. For this reason, he thought, actors in the present tended to develop the habit of “quoting primeval history.”45 These citations could prompt recollections of the promise inherent (but as yet unrealized) within the prior form. “Each epoch not only dreams the next,” Benjamin wrote, “but also, in dreaming, strives toward the moment of waking.”46

In the dream in which, before the eyes of each epoch, that which is to follow appears in images, that latter appears wedded to elements from prehistory, that is, of a classless society. Intimations of this, deposited in the unconscious of the collective, mingle with the new to produce the utopia that has left its traces in thousands of configurations of life, from permanent buildings to fleeting fashions.47

Analytically, such images can be used to clarify the desires that compel people to persevere. Politically, they can be mobilized to stimulate action in pursuit of those aims. However, as Susan Buck-Morss has pointed out, while “the real possibility of a classless society in the ‘epoch to follow’ the present one revitalizes past images as expressions of the ancient wish for a social utopia in dream form . . . a dream image is not yet a dialectical image, and desire is not yet knowledge.”48 In order to move from one state to the other, the attributes associated with the dialectical image must first be made clear.

In his arcades project, his essay on the concept of history, and elsewhere, Benjamin advanced a series of propositions concerning dialectical images, their characteristics, and their effects.49 Constellating fragments of matter and memory to prompt an absolutizing reflection, he imagined that such images could force people to consider how they might act upon history as such. In one early formulation, Benjamin clarified, “it’s not that what is past casts light on the present, or what is present its light on what is past; rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation.”

In other words, image is dialectics at a standstill. For while the relation of the present to the past is a purely temporal, continuous one, the relation of what-has-been to the now is dialectical: is not progression but image, suddenly emergent.50

In contrast to the wish images described in “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century” (images that refracted their profane promise through the analytic distortions of a dream state shaped by myths and visions), the dialectical image was inseparable from the recognition of the revolutionary possibility inherent in what Benjamin called “the now.” Commenting on the distinct but interrelated character of these two image forms, Buck-Morss proposed that, with the dialectical image, wish images were “negated, surpassed, and at the same time dialectically redeemed”51—which is to say: the dialectical image completes the wish image dream by exposing it to the shock of recognition. In this way, it makes both the promise and the means by which it might be fulfilled visible all at once.

By acceding to the demand the dialectical image brought in its wake, Benjamin imagined that people might come face to face with “a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past.”52 For this reason (and as early as 1929), he proposed that revolution meant discovering “in political action a sphere reserved one hundred percent for images.”53 Only from within this sphere, he thought, was it possible to address history, “the world of universal . . . actualities,” directly.54 Such an account can’t help but disclose a metaphysical provenance. But if Benjamin’s Marxism was more than a broken homage, how then should this appeal to the universal be understood?

According to Buck-Morss, Benjamin envisioned communism as a “harmonious reconciliation of subject and object through the humanization of nature and the naturalization of humanity.”55 Conceived in this way, communism is itself a project of absolution, a pathway to reconciliation made possible through the profane discovery-creation of the world’s perfect, non-contradictory identity. By collapsing the distinction between revolution and absolution, and by marshaling a reflection that augured completion, Benjamin rediscovered what Buck-Morss took to be an important “ur-historical motif” in Biblical myth. As the wish image makes clear, however, such motifs can’t simply be deployed “symbolically, as aesthetic ornamentation,” since doing so risks refurbishing the dream from which people strive to awaken. Instead, these motifs must be rediscovered “actually, in matter’s most modern configurations.”56 It is from within this realm that the dialectical image arises, and it is here that the metaphysical appeal to the universal finds its own point of sublation.

VII

Despite his invocation of carefully selected profane objects, Benjamin remained hard pressed to provide concrete examples of dialectical images that could yield the effects with which he associated the concept. Still less was he able to demonstrate how such an image might reliably be produced. Indeed, when reading the “Theses,” it’s difficult to avoid the impression that dialectical images are discovered solely by chance. But if such images are only ever haphazard discoveries upon which one stumbles “at a moment of danger” (and if, still more, they threaten after having flashed up “never to be seen again”), attempts to operationalize Benjamin may seem pointless.57

A solution suggests itself by turning to Benjamin’s treatment of “thinking,” a concept he used to denote the active, subjective moment in the reflection process. No mere contemplative act, thinking for Benjamin was an operational premise, the concrete means by which the citable elements of material history were brought into constellation. On this basis (and despite the limits he confronted with respect to his own creations), it becomes clear that, through his ongoing experiments with literary montage, Benjamin was actively struggling not only to discover but also to produce dialectical images in writing.58 In the following sketch for what would become thesis XVII of his essay on the concept of history, Benjamin makes the connection between thinking and dialectical images clear:

Where thinking comes to a standstill in a constellation saturated with tensions—there the dialectical image appears. It is the caesura in the movement of thought. Its position is naturally not an arbitrary one. It is to be found, in a word, where the tension between dialectical opposites is greatest. Hence, the object constructed in the materialist presentation of history is itself the dialectical image.59

Along with clarifying the bonds that unite thinking, construction, and the dialectical image, Benjamin’s comments also confirm that the dialectical image is marked by two discrete phases. When considered from the standpoint of its apprehension, the image is confronted as an immediate and absolute presence (and it’s for this reason that Benjamin so frequently invoked shock as an analytic category). When considered from the standpoint of its production, however, the shock of recognition reveals itself to be epiphenomenal, a salutary effect of the mediated constellation process. Observing this same duality in her own treatment of Benjamin’s project, Buck-Morss recounts how, “as an immediate, quasi-mystical apprehension, the dialectical image was intuitive. As a philosophical ‘construction,’ it was not.”60

In addition to the internal division between the moment of thinking-construction and the subsequent moment of apprehension-recognition to which it gives birth, however, the dialectical image appears to be riven once more. Here, one detects a split between the initial phase of analytic apprehension and the subsequent decision through which the image’s status is confirmed. As with Fanon, for whom “each generation must . . . discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it,”61 the dialectical image demands both the discovery of the animating desire and the subsequent fulfillment of that desire through struggle. The shorter the interval between these two phases, the more perfectly the image corresponds to Benjamin’s conception.

The secondary literature on Benjamin has thus far and for the most part ignored the centrality of the latter demand, which pertains to struggle. This may suggest that Benjamin’s mode of analysis is better suited to heuristic excitation than to insurrectionary plotting—and that, for every comrade willing to take a “leap in the open air of history,”62 there will always be another one begging to know what the hell you’re talking about. Then again (and this is the wager), perhaps the uncertainty with which we confront the dialectical image today is itself but a symptom of our ongoing struggle to wake up.

VIII

In the interest of demonstrating how Benjamin’s method might be operationalized and thus further comprehended and made actionable today, I want to fashion a constellation out of historical fragments chosen precisely because, at first glance, they may seem distant from our main point of inquiry. In addition to keeping us from becoming ensnared in a reactive posture vis-à-vis contemporary horrors, this distance shall also help to confirm the truth of Benjamin’s insight that—through careful selection and absolutizing reflection—even the most inconspicuous fragments can help bring the present into a critical state.

In assembling this construction, I have been guided by Benjamin’s methodology (though, as Benjamin maintained, it really is better called a “trick” than a method). By showing how this method can be used to guide “thinking,” I hope to demonstrate how it might be cultivated and operationalized in other contexts. In the case of this particular constellation, I pay special attention to those lingering visual traces that undermine linear conceptions of time while prompting the past to “bring the present into a critical state.” Concretely speaking, this means that the analysis leads inexorably toward the moment of decision demanded by politics. And while there may well be other ways to arrive at this point, I hope to make clear that Benjamin’s approach—once operationalized—can’t help but deposit us there as a matter of course.

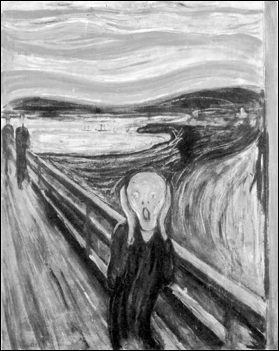

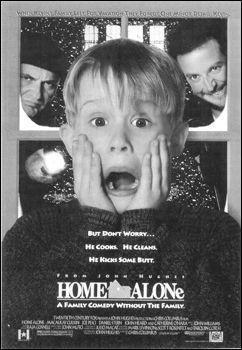

What, then, should we make of the curious historical relay that binds the Scream Edvard Munch unleashed in 1893 to the signature gesture that would launch a miserable child actor to stardom nearly a hundred years later?

Figure 1. Edvard Munch, Scream (1893) |  Figure 2. Home Alone (1990) |

It is useful to begin by considering the social and political realities to which these images give expression.63

According to art historian Øivind Storm Bjerke, The Scream positioned Munch firmly within the symbolist tradition, which he took to be “a chiefly reactionary trend within the art of the late 19th century.” Such an appraisal owed to the fact that, as a movement, symbolism “rejected modern industrialized society and looked back on the pre-industrial era with nostalgia.” Rather than “confronting contemporary social injustice” directly, the symbolists instead became a “late-Romanticist attempt to seek comfort in the idea of something original and genuine; a condition of harmony between human beings and nature, which industrialism . . . had ended.”64

To judge the validity of this account, one might recall a poetic sketch that Munch scrawled in his journal around the time he painted The Scream. Beset by turmoil, and walking by the sea one evening during “a time when life had ripped [his] soul open,” Munch saw a sun that, in setting, looked to him like “a flaming sword of blood slicing through the concave of heaven.” Indeed, the sky itself took on a hue “like blood—sliced with strips of fire” while “the hills turned deep blue” and the fjord itself became “cut in cold blue, yellow, and red.” Surrounded by this scene of “exploding bloody red,” Munch confessed to having “felt a great scream.”

And I heard, yes, a great scream—the colors in nature—broke the lines of nature—the lines and colors vibrated with motion—these oscillations of life brought not only my eye into oscillations it brought also my ears into oscillations—so I actually heard a scream.65

Such foreboding may not have been without foundation. As art historian J. Gill Holland has noted, “the supposed spot over the Oslo Fjord where the screamer stands was located above a slaughterhouse and a mental hospital, and sounds from each were said to be audible on the road above.”66 Elsewhere in his journal, Munch recounted a vivid slaughterhouse scene that seems to corroborate Holland’s apocryphal account. In a poem grimly entitled “The Smile,” Munch stands transfixed as an ox is “led in with its head half through the door so that the rear remains in the slaughter room and the head peeping out of the door into the passage.”67 At the moment of death, the slaughtered animal yields The Scream’s wild palette:

—It shines in

the white and

yellow white fat and tallow—against the powerful

red and violet blue

flesh—which drips

blood water.68

These experiences would take their toll. By the turn of the century, Munch began recounting feelings that were tantamount to being home alone in the world. In the period following his Scream, he even admitted that he had “[given] up hope of ever being able to love again.”69 Under such conditions, it was natural that his journal became a cartographic sketch of the world’s emptiness. “I walked one evening lonesome by the sea,” he recalled. “It sighed and swished among the rocks—there were long gray clouds along the horizon—it was as if everything had died—as in another world—a landscape of death.”70

Searching desperately for one real thing and recoiling from modernity’s ominous shadow, Munch’s affective posture became a textbook example of what Bjerke took to be symbolism’s reactionary anti-capitalism. Viewed from the standpoint of the present, where poor-little-rich-girl stories are more likely to elicit sneers than sympathy, suffering of this kind may now seem quaint. Nevertheless, contemporary developments have done little to invalidate—and much less to resolve—the anxieties to which Munch succumbed. By following citations and image traces in the Benjaminian fashion, we learn that The Scream Munch unleashed at the dawn of the twentieth century would go on to become one of the most frequently referenced images of all time.

According to art critic Tina Yarborough, “numerous artists” during the latter half of the twentieth century “presented, paraphrased, and made a pastiche of Munch’s art.” Taken together, these citations ensured that Munch himself would become “one of the twentieth century’s most oft-cited artists.”71 For Yarborough, “Munch’s message and its popularity” are nowhere more apparent than in the “ubiquitous appropriation” of The Scream. Back in 1895, Munch made a lithograph of the work to facilitate its reproduction. This initial act would augur countless repetitions. Today, The Scream has become “commonplace in . . . mass culture” while at the same time being “appropriated . . . by well-known artists.” As a result, the image now infuses “the realms of both high and low art” simultaneously.

The Scream in mass culture has spawned everything from television commercials . . . to political cartoons and advertising campaigns. . . . Television personality Dame Edna Everage fashioned The Scream into a dress, and the motif has even prompted published personal responses to the intellectual satisfactions derived from the “Scream Giant Inflatable Blow-up Dolls.”72

How are we to understand this proliferation? According to Yarborough, “even though [The Scream] may have begun as a naturalistic autobiographical experience, by the final painting, Munch had rejected narrative content and depersonalized its meaning.” By presaging the absolute, the image thus became “a more general investigation into the precarious conditions of individuality” under “capitalist systems of control.”73

In 1986, artist Andres Serrano exhibited a work entitled The Scream featuring “a dead coyote . . . strung up by a noose.” For Yarborough, Serrano’s image was “a primal shriek that . . . reache[d] back through America’s ugly history” even as it invoked “current border clashes.”74 In this moment, as citation gives way to connotation, the entirety of history seems to become compressed within the image frame. Indeed, in Serrano’s reprise, Yarborough found evidence that “Munch’s symbols reverberate across historical lines.”75 For this reason, and despite the dramatic contextual shift it enacts, the Serrano can be said to hold true to the substance of Munch’s original.

But this appropriation did not exhaust the citation’s range.

IX

Directed by John Hughes and released on November 16, 1990 (nearly a hundred years after Munch’s Scream), Home Alone grossed $17 million during its opening weekend and remained number one at the box office for twelve weeks straight. The film’s success owed nothing to critics, who did little to conceal their sneering contempt. According to Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly, Hughes had delivered little more than a “sadistic festival of adult-bashing.” 76 Nevertheless (or perhaps for this very reason), the movie earned $285,761,243 at the domestic box office and became the top-grossing film of the year. It remains the highest-grossing live-action comedy of all time.

The film’s opening scene invites viewers into a bourgeois home bursting with activity but bereft of connection. After being ignored and belittled by family members gathered for an impending vacation, a prepubescent Kevin (Macaulay Culkin) declaims, “this house is so full of people it makes me sick. When I grow up and get married, I’m living alone!” The scene degenerates, and Kevin yells at his mother: “I don’t want to see you again for the rest of my whole life.” Once settled in bed, his sentiment becomes a conscious, verbalized wish: “I wish I could make them all just disappear.”

Like Peter Pan before it, Home Alone derives both its tension and its dramatic appeal from the entwined agonies of bourgeois domestic boredom and the Oedipal drama. For both J.M. Barrie and John Hughes, parents are cast as ambivalent objects. Dispatched as irrelevant, they nevertheless remain sources of fantastic longing. In both stories, domestic restriction prompts wishful projection. At their threshold, the fantasies take on a life of their own. Upon discovering that his wish seems to have come true, Kevin settles into an ersatz adulthood. After passing a razor over his face in mimetic anticipation of the adult he will become, he applies aftershave and delivers the film’s canonical Scream citation. The scene is treated as comedy, and the audience is urged to forge an empathic identification with the protagonist as he struggles to learn the ropes.

At the end of his first day in the new adult role, however, Kevin has already begun regretting his wish. Sitting on his parents’ bed and looking at a family photo, he insists that he “didn’t mean it.” At this point, the film resolves the problem by changing the substance of the dream. In the end (and following his slapstick struggle with blundering adversity), Kevin manages to have it both ways—first by wishing his family away and then by wishing them back. In the interim, he gets to grow by confronting the reality his dream called into being. Transformed by his adventure, he opts in the end to keep the details to himself. At its core, Home Alone is an extreme example of wish fulfillment. The autonomy won through the struggle to transcend childhood innocence is secured even as childhood itself is reaffirmed.

When considered in constellation, The Scream’s echo in Home Alone makes us witness to an unsettling transubstantiation. In less than a century, tragedy returns to the world stage as farce. But while the latter state may seem more agreeable from an affective standpoint, the repetition should not be mistaken for resolution. Because we did not know how to overcome the problems to which Munch alerted us (because our anti-capitalism remained reactionary and Romantic), we made a joke of them instead. What remains most striking about Culkin’s Scream citation, then, is not so much that the same image—the same situational iconography—can signify two distinct and diametrically opposed contents (as might be presumed by those inclined to grant analytic primacy to the signifier), but that the content, the signified, the course of the depicted drama itself, remains ostensibly the same. Only our affective relationship to it has changed.

The transposition from existential terror to sympathetic laughter (the displacement of affect from Munch’s homunculus to Macaulay Culkin’s Kevin) speaks strongly of resignation. If laughter, as psychoanalysis suggests, is a means of diffusing tension without resolving it, then Culkin’s oblique citation is unquestionably political in its implications, if not in its intent. According to Fredric Jameson, the feeling of vertigo brought on by the modern era (the very feeling that led Munch to both hear and see his Scream) reappears under late-capitalism as “euphoria.”77 How, then, might we come to terms with the perpetual alienation to which Munch alerted us if vertiginous euphoria has itself become a desperate and compensatory source of pleasure?

Instead of resolving historical tensions, the bourgeoisie fetishistically displaces them. Instead of realizing the desires it stimulates, it binds them to the commodity form. Munch never stood a chance. And try as we might, we can’t laugh it off forever. In the end (and as Benjamin proposed in a different but parallel context), Culkin’s Scream can only be contemplated with horror.78 It alerts us not solely to the estrangement of our social reality, which is indistinguishable from Munch’s except when it is worse, but also to the cowardice of our comedic displacements—the dangers of the succor we glean from wish fulfillment.

X

Following Benjamin (though its shortcomings are my own), this constellation was produced quite by chance. Prompted by a casual observation regarding Culkin’s citation “without quotation marks,”79 I became curious about the social and economic realities to which these images gave expression. On this basis, it became possible to document the historical interconnections between their discrete moments, and to see how—through the constellation itself—the past might bring the present into a critical state. The textual evidence I marshaled to substantiate the connection was selected on a predominantly intuitive basis. As Benjamin proposed, I allowed these material fragments to come into their own by making use of them.

By outlining the methodological coherence of Benjamin’s work while operationalizing his premises to consider an illuminating case study, I hope to have shown how contemporary scholars might further the project that Benjamin began but could not complete. Munch’s Scream became distorted through the course of its historical development. But these corruptions (these moments in the medium, these traces of the image’s multi-faceted reflection) prove to be illuminating in their own right. By constellating this material, and by substituting a political for a historical view of the past, 80 we come face to face with decision.

Operationalizing Benjamin in this way reveals his work to be less enigmatic, more comprehensible, and of greater immediate use than the voluminous secondary literature seems to suggest. This outcome should be of interest to scholars who recognize that, both as a discipline and a vocation, cultural studies might amount to more than a means of interpreting the world. By acknowledging the desire for absolution underlying human history while alerting us to the limits inherent in the forms through which this striving has thus far found expression, Benjamin’s method leads inexorably toward political reckoning.

More than anything, Benjamin demonstrates how artifacts, when brought into constellation, can become the basis for a history of capitalism that is at the same time an archaeology of desire, a phylogenetic tale recounting the struggle for freedom that ends with decision in the time of the “now.” It is from here that we too must begin.

Notes

- Angela McRobbie. “The Passagenwerk and the place of Walter Benjamin in Cultural Studies: Benjamin, Cultural Studies, Marxist Theories of Art, “ Cultural Studies 6, no. 2 (1992): 147–169. ↩

- It is important to note, however, that—despite this ubiquity—there have thus far been virtually no engagements with Benjamin in the pages of Lateral. ↩

- This approach to heading off the impossible future telegraphed by our present is the thread uniting the investigations included in my Premonitions: Selected Essays on the Culture of Revolt (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2018). ↩

- There is a tendency in the social sciences to conceive of “operationalization” as a means of clarifying the meaning of a concept or devising a more concrete understanding of the phenomenon to which it refers by finding its expression in a more observable phenomenon with which it might be correlated. In opposition to this tendency, and following Benjamin’s insight that fragments of material culture only come into their own (i.e. only become comprehensible) by “making use of them,” I conceive of operationalization as a form of deliberate engagement uniting ideas and action. At its threshold, Benjamin’s injunction to force the fragments of material culture into constellation so that they might reveal their synechdochical status must be applied to the fragments of Benjamin’s work as well. Only in this way do the implications and overarching coherence of this work become evident. This process is best achieved through the course of purposeful, active investigation. ↩

- Pierre Missac, Walter Benjamin’s Passages (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995), 15. ↩

- In Convolute N of The Arcades Project, Benjamin highlighted the “necessity of paying heed over many years to every casual citation, every fleeting mention of a book.” Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, translated by Howard Elland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 470 ↩

- Zsuzsi Gartner, Better Living Through Plastic Explosives (Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2011), 43. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” translated by Edmund Jephcott in Reflections, (New York: Schocken Books, 1978), 225 ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “One-Way Street,” translated by Edmund Jephcott in Reflections, 61. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, translated by Howard Elland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 460. ↩

- In making this argument, I am not suggesting that Benjamin somehow knew at the beginning of his intellectual career what themes and approaches he would be using at its close. I acknowledge a clear periodization in Benjamin’s intellectual biography. Nevertheless, it is important to note that reducing such a periodization to a story of biographical influences is at odds with Benjamin’s own approach to historical reckoning. Consider, for instance, how, in “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” he proposed that each epoch “bears its end in itself and unfolds it—as Hegel already saw—with ruse.” It is my contention that, in order to be consistent, this insight must be applied to any periodization of Benjamin’s intellectual output as well. “Paris Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” translated by Edmund Jephcott in Reflections, 162. ↩

- Theodor Adorno, “Theordor Adorno Letters to Walter Benjamin,” Aesthetics and Politics: The Key Texts of the Classic Debate Within German Marxism (New York: Verso, 2002), 129. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,” translated by Edmund Jephcott in Reflections, 182 ↩

- Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life (Cambridge, MA: Belknap / Harvard University Press, 2014), 7. ↩

- Eiland and Jennings, Walter Benjamin, 4. ↩

- Eiland and Jennings, Walter Benjamin, 7. ↩

- Benjamin, Arcades Project, 463 ↩

- Benjamin, Arcades Project, 456. ↩

- Benjamin, Arcades Project, 458. ↩

- Benjamin, Arcades Project, 459. ↩

- Benjamin, Arcades Project, 460. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “The Concept of Criticism in German Romanticism,” translated by David Lachterman, Howard Eiland, and Ian Balfour in Selected Writings Volume 1, 1913–1926, (Cambridge, MA: Belkap Harvard, 2004), 159 ↩

- Benjamin, “The Concept of Criticism,” 158. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “The Life of Students,” translated by Rodney Livingstone in Selected Writings, 37. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” translated by Harry Zohn in Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 263. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 254. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 264. ↩

- Theodor Adorno, “Introduction to Benjamin’s Schriften” in On Walter Benjamin: Critical Essays and Recollections, ed. Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1988), 5. ↩

- Adorno, “Theodor Adorno Letters to Walter Benjamin,” Aesthetics and Politics, 111. ↩

- Adorno, “Theodor Adorno Letters to Walter Benjamin,” Aesthetics and Politics, 130. ↩

- Gershom Scholem, ed., The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem 1932–1940 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 197. ↩

- Gershom Scholem, “Walter Benjamin and His Angel,” in On Walter Benjamin, 54. ↩

- Scholem, The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, 207. ↩

- Scholem, The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, 206–207. ↩

- Missac, Walter Benjamin’s Passages, 22. ↩

- Gershom Scholem, “Walter Benjamin and His Angel,” 82. ↩

- For example, Scholem argued that, for Benjamin, “paradise is at once that origin and the primal past of man as well as the utopian image of the future of his redemption—a conception of the historical process that is really cyclical rather than dialectical.” Scholem, “Walter Benjamin and His Angel,” 83. ↩

- J. V. Stalin, “Political Report of the Central Committee to the Sixteenth Congress of the C.P.S.U.(B.),” Marxists Internet Archive, online version published 2000, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1930/aug/27.htm. ↩

- Scholars frequently describe Benjamin’s Marxism by referring to the influential role played by Bertolt Brecht and other figures in his intellectual biography. I do not dispute the value of such an approach; however, focusing on it exclusively prevents us from appreciating the intrinsic coherence of Benjamin’s intellectual development, which embraced Marxism only to further actualize it through the synthetic dynamics of reflection. ↩

- Georg Lukács provides the classic account of both this problem and the means of its possible resolution in “What is Orthodox Marxism?” History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1988). ↩

- Karl Marx, “Letter from Marx to Engels In Manchester,” Marxists Internet Archive, accessed November 21, 2020, http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1868/letters/68_03_25-abs.htm. ↩

- Indeed, Marx’s observations regarding the bourgeois revolution’s debts to “Rome reincarnate” are quintessentially Benjaminian. Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Selected Works, Volume I (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1973). ↩

- Louis Althusser, For Marx (New York: Verso, 2006 {1962}). ↩

- Karl Marx, Capital, Volume I (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1954). ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” Reflections, 157. ↩

- Benjamin, “Paris,” 162. ↩

- Benjamin, “Paris,” 148. ↩

- Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1992), 148. ↩

- Although the term does not appear in the latter work, the concept finds expression through cognates like “monad” and “true image of the past.” In line with Michael Löwy’s reading of the “Theses,” I take these terms to be synonymous. As Löwy recounts, “in a first version of {Thesis XVII} to be found in the Arcades Project, in place of the concept of the monad there appears that of the ‘dialectical image.’” Michael Löwy, Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s ‘On the Concept of History’ (New York: Verso, 2005), 132. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 462. ↩

- Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing, 146. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 263. ↩

- Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,” translated by Edmund Jephcott in Reflections, 191 ↩

- Benjamin, “Surrealism,” 192. ↩

- Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing, 146. ↩

- Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing, 146. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 255. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 460. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 475. ↩

- Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing, 220. ↩

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Press, 1963), 206. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 261. ↩

- As Benjamin outlined in his notes for the arcades project, “it is not the economic origins of culture that will be presented, but the expression of the economy in its culture. At issue, in other words, is the attempt to grasp an economic process as perceptible Ur-phenomenon, from out of which proceed all manifestations of life.” Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 460. ↩

- Øivind Storm Bjerke, “Scream as Part of the Art Historical Canon,” The Scream (Oslo, Norway: Munch Museum, 2008), 15. ↩

- Edvard Munch, “We Are Flames Which Pour Out of the Earth,” in The Private Journals of Edvard Munch: We Are Flames Which Pour Out of the Earth, ed. and trans. J. Gill Holland (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), 64–65. ↩

- Munch, The Private Journals, 2. ↩

- Munch, The Private Journals, 42. ↩

- Munch, The Private Journals, 144. ↩

- Sue Prideaux, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 152. ↩

- Munch, The Private Journals, 176. ↩

- Tina Yarborough, “The Strange Case of Postmodernism’s Appropriation of Edvard Munch,” in Edvard Munch: An Anthology, ed. Erik Mørstad (Oslo: Oslo Academic Press, 2006), 191, 193. ↩

- Yarborough, “The Strange Case of Postmodernism’s Appropriation,” 192–193. ↩

- Yarborough, “The Strange Case of Postmodernism’s Appropriation,” 192. ↩

- Yarborough, “The Strange Case of Postmodernism’s Appropriation,” 199. ↩

- Yarborough, “The Strange Case of Postmodernism’s Appropriation,” 199. ↩

- Gleiberman, Owen. “Home Alone” ew.com. https://ew.com/article/2007/07/25/home-alone-2/. ↩

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), 28. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 256. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 458. ↩

- Benjamin, “Surrealism,” 182. ↩