What is, or was, on the mind of Marley in those slow, ganja inspired, Jamaican plaints about Babylon and the march to an African Zion, is not on the minds of those who play him at parties in Chicago. Again, this is no argument against the alternative uses to which music can be put, but it does add a note of clarity about the limits of hybridity in the widely advertised, but still somewhat dubious, emergence of a world culture.

—Timothy Brennan, “World Music Does Not Exist”

Kadri Gopalnath passed away in 2019. The renowned Carnatic saxophonist’s obituary in The New York Times said that he “first heard the alto saxophone at a performance by the Mysore Palace Band, a holdover from the years of British rule that mixed Indian and European repertoire.”1 Henceforth, he brought the saxophone to South Indian classical music and influenced many Indo-Jazz musicians. I had not heard of him before he was mentioned to me by an American classmate in Buffalo, New York.

This is how music is heard: in bottomless streams. We need not step into different music venues on different nights—all bracketed by style, genre, region, and language—to listen to sounds new and unfamiliar. Nor is our familiarity with a musical tradition contingent on where our dot is on the map, though it is contingent on class, native language, and dominant second-languages. As a middle-class middle-school student in Delhi many years ago, I never listened to anything other than music from Hindi cinema, until I made friends from “better” neighborhoods who made me listen to, of all things, Owl City. Much later I would begin listening to jazz to be able to make intelligent conversation with my English degree classmates in college, and begin recollecting the many times I had heard echoes of the syncopated oddity in Bollywood music.

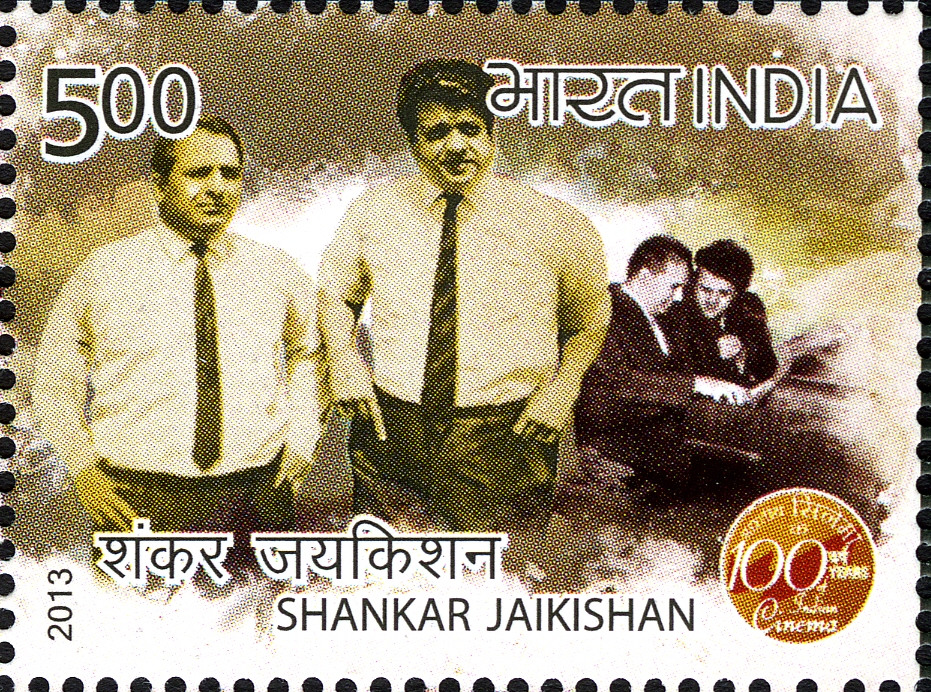

This “global imagination” is what Veit Erlmann thinks of as us reaching out beyond our immediate experiences in a gesture of understanding other contexts by transplanting and occasionally supplanting our knowledge into them.2 The album Raga-Jazz Style,3 released in 1968 by Hindi-film music composers Shankar-Jaikishan, faces this global imagination with music which comes neither from a linearity of tradition, nor from a set of rules developed in insular conditions, and not from one common historical consciousness. In this album, there is no protectionism for the Hindustani music tradition, and there is no assumption of any protectionism for jazz. It is music from nowhere because it revels in a collaborative autonomy which rejects located-ness, and because its sound is so multifariously recognizable that we cannot fixedly recognize it at all.

The album has been made freely available on deejay.de in a re-issue by Outernational Sounds.4 This is the track list for the album:

A1: Raga Todi

A2: Raga Bhairav

A3: Raga Malkauns

A4: Raga Kalavati

A5: Raga Tilak Kamod

A6: Raga Miyan Malhar

B1: Raga Bairagi

B2: Raga Jaijaiwanti

B3: Raga Mishra Pilu

B4: Raga Shivranjani

B5: Raga Bhairavi5

As can be seen here, the album has eleven short pieces, each of which is named after the raga whose melody is folded into the jazz mold. We will go into more detail about Hindustani music in some time, but for the moment let us consider, or rather catch a glimpse of, what the album does with its sources. Take the third track on the album, titled “Raga Malkauns,” which picks up one of the oldest “parent ragas”6 of Hindustani music and renders it into a sub-three-minute composition with a dominant saxophone set to the rhythm of the drums, and a short sitar and table section in the middle. The restricted length makes it into an energetic, tightly composed piece of music tinged with Latin jazz sounds; it remains melodically recognizable as Malkauns even as it is performatively transformed. I say this with Adrian McNeil’s work on Hindustani music in mind. McNeil understands a raga as an “unfolding,”7 rather than a playing out, of the composition embedded within the raga, different from most Western sensibilities of music where a composition would be an “independent bounded entity against which the concept of improvisation can be oppositionally positioned.”8 For McNeil, the bandish, which is an element of a raga and is the closest conceptually to a conventional understanding of a fixed composition within the raga, still functions like a “seed idea”9 which provides a “launching pad for creativity”10 within the scaffolding provided by the raga and therefore is still different from the “complete and intentionally bounded”11 understanding of composition in the west. The Malkauns of Raga-Jazz Style adapts the seed idea of the raga into a bound composition, simultaneously freeing it from the scaffolding of the raga and sectioning it into a neatly arranged musical track, fretting over little by way of rules and prescriptions. For me at the very least, the recognizability of the raga in the piece, reminding me of some of the longer performances of raga Malkauns I have heard in the past, soon ebbs and dissolves as it takes on a jovial, funky life of its own.

Much like this, each of the eleven short pieces in this album can be heard as examples of unfettered creativity—of that nowhere sound I mentioned earlier. But in calling Raga-Jazz Style a sound from nowhere, I am already rejecting the question which should face instances of seemingly free creative impulses: Is creativity without its own weight of history? Where does Raga-Jazz Style come from, if not from an entirely free association of ideas meant to simply create melodious music? Might it actually come from somewhere?

The possible answer we are looking for here can come from two places: first, from a study of the historical conditions which made this creative association possible. This study has a tenuous but productive relationship with what has come to be known as “global history” which puts emphasis on connections and integration rather than on a “rhetoric of ‘influence.’”12 I say tenuous because in talking about the relationship between jazz and Hindustani music in this interfusion, we do have to address, albeit in passing, the power structures which determine the “positions” taken up by both of them. Global history does not ignore such inequalities, but it does resist methods of history which study origins as being rooted in nationality, and here we begin with America and India—albeit to eventually move away from narratives of origins.

The second possibility for an answer comes from our listening of the album. As mentioned earlier, it is a collection of eleven tracks which interfuse Hindustani music with different forms of jazz. Ragas like Todi, Bhairav, and Kalavati, among others, are rendered in styles such as bebop, blues, cool jazz, swing, and waltz, for pieces which last around three to five minutes each. The arrangement combines brass instruments and the drums with the sitar, the flute, and the tabla, amid larger orchestral elements. While it is tempting to go into a formal discourse about the intricacies of each of these eleven pieces, I am here more interested in getting to the album, rather than getting into the album. What concerns me more is, for example, whether the album can be placed within the prominent tradition of Indo-Jazz at all, because it is unlike most prominent Indo-Jazz. We do know that the album follows from a then nascent tradition of Indian music transported to the West and sometimes brought back to India, which according to Peter Lavezzoli’s account is a process that begins in 1955.13 Through the respective, and eventually connected histories of Hindustani music and jazz, we can listen for the constituent sounds of “raga-jazz,” and understand their coming together to find the root of the creative impulse which composes music from the world for the world, all the while being of nowhere.

A Short History of Worldly Jazz

Universalist and ethnically assertive points of view, it must be emphasized, often coexist in the same person…. On the one hand, performers are proud to play music that inspires musicians and audiences beyond its culture and country of origin; on the other, many object to the attempts of non-African Americans to gloss over the African American cultural origins and leadership in the music through the language of equality.

—Ingrid Monson, Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction

Let me start here with something fairly obvious: Jazz is not a monolith created in Dixieland. Through a century-long history, it has shaped and reshaped itself from its vaudevillian and ragtime roots into swing, big band, bop, cool jazz, and free jazz.14 During this time, it has undergone repeated renewal by standing under varied umbrellas such as orchestral, classical, and pop, transporting and translating itself to interfuse with music from across the world. Formally, it is not a monolith.

But one can argue for a monolithic cultural root for jazz, seeing as even before the early 1900s, what would eventually become the vivacious rhythmic flair of the music had already been forced to enter the US with the slave trade, which is the moment of this narrative where framing jazz history within national boundaries is no longer possible. The rhythms which came to define the sound were consecrated in the folk memory of Black Americans in the form of field songs, honks, shouts, calls, and responses.15 To Ajay Heble, studying dissonance in jazz, it seems “odd that a music so clearly rooted in social processes, in struggles for access to representation and identity formation, should give rise to such formalist models of aesthetic analysis.”16 In one of these analyses, the constant renewal of jazz moving towards the dissonance of Charlie Parker’s bebop or Ornette Coleman’s free jazz can be heard as a desire to keep sound shocking, and to keep moving away from spaces in which it was becoming too familiar and comfortable for white audiences.17

When this music is taken away from its social rootedness and transported to fuse with African, South American, Asian, and subcontinental musical traditions, including Hindustani music, is this to be read as a history of deracination? Of a sound being made of the world against its will, becoming world music to audiences unaware of the ethnic and linguistic consciousness which informs the sounds they are listening to? After all, an understanding of world music, the academic definitions of which we will get to in a few moments, has to go beyond creative collaboration. A jazzist like Herbie Hancock too, delivering lectures on “The Ethics of Jazz” at an event introduced by Homi Bhabha, may talk of the “touch,” the “passion,” and the “feel” for sound and musical listening in jazz which have come to define an intensely spiritual ethic of composing music. But, he admits, even the creative hospitality of a jazz stage where no musician is trying to upstage or be in subservience to another is tied to issues of social justice, globalization, and neo-liberalism which give direction to the collaborative aesthetics of jazz.18 One way to think through this problem is to question whether jazz is world music at all, or better yet, to think of what world music really means.

Timothy Brennan offers a definition of world music partly offset by the title of his essay, “World Music Does Not Exist.” What he means to say with this title is that world music does not exist as an unproblematic creative space with the freedom to borrow or co-opt or sample. Instead, it is for him is a hope wherein one can conceive of “a different kind of world, free from imperial domination” where alternative models of creating and listening to music can “subvert the ideological parochialism of Euro-American popular music . . . helping to dismantle the cultural logic of Western popular music.”19 The term world music, however, as it is often commercially used, is less about understanding the world’s music and more about sounds being made to enter new soundscapes, and quite importantly, new markets.20 Understanding the world’s music is something that ethnomusicologists do, and not music companies, I would imagine. Gerry Farrell has a jocular quip about this: “World Music is fun, colorful, sexy, and saleable, whereas ethnomusicology is serious, rigorous, dull, and academic.” For him, world music is the “aural equivalent of the package holiday.”21 American Jazz in this case might as well be an established market of listening consumers where the product of Hindustani music is brought in as a passing fad until another music takes its place, much like the consumer cycle of any new-fangled product. But that means I would be contending that jazz is the big-bad-cannonball in its transaction with other musical traditions, and that it co-opts or even appropriates other musical traditions as the more powerful partner in any musical collaboration. And this is not true.

This becomes clear in two arguments by Joachim-Ernst Berendt in a piece from 1968. The first and primary contention is that jazz is by birth syncretistic in that it was the result of an “encounter” between Africa and Europe, borne out of a struggle for representation and cultural space in the American milieu.22 Second, after the Second World War, there was a breakdown of dialogue between the Black and the white man.23 The growing sense of exasperation amongst figures like Malcolm X made space for a breaking away from Christianity as several Black jazz musicians embraced Islam and took up Arabic names too, feeling a stronger comradeship not with the white American but with others who had struggled with their cultural identities through colonialism.24 Damon Phillips, in his book Shaping Jazz: Cities, Labels, and the Global Emergence of an Art Form, has another interesting observation to this end. He notes that jazz which came from “disconnected” cities, that is, cities which were not seen as centers of the music in the way New York or Chicago were, often had more appeal on account of it having more novelty25—even the market of jazz rewarded the decentering of its music. This is not to quell any and all discussion of hierarchies when jazz meets Hindustani music, but rather to demonstrate that the claim for both forms of music to meet halfway is one which is possible to make, or imagine.

Indian Jazz and the American Hindustani

Speaking of hierarchies, or the lack thereof, the first facet of the encounter between Hindustani music and jazz was still conspicuously colonial, as Warren R. Pinckney Jr.’s work suggests. Jazz in 1920s came in the form of touring bands which mostly performed for Europeans audiences in India.26 By the 1930s and 1940s, musicians from Goa and Bombay were performing regularly in spaces frequented by the educated urban bourgeoise, and it was for a time a “lucrative business” in the cities.27 This era drew to a close with Western developments in jazz leaving the Indian big-band version behind, and also with a rejection of Western cultural imports after the Indian freedom struggle.28 While a small stratum of Anglo-American listeners in Bombay kept the fledgling jazz tradition of India alive, that too withered away with most of that audience emigrating to the West.29 Jayson Beaster-Jones traces the influence of Goans in Indian Jazz to Portugese colonialism which was different from British indirect rule: “Their [Goans’] education in Western classical and international popular musics, as well as their proficiency in Western musical instruments, made them valuable contributors to the musical life of the British colonialists.”30 This confluence between India and American Jazz, which was not exactly a fusion of two musical traditions yet, set the stage for what was to happen in the 1960s.

This second facet of the encounter is much closer to the “saleable” aspect of world music mentioned earlier. It is close to 1960s when Indian music becomes a part of Western pop-culture. In an exchange effected by the demands of the market, Farrell believes that there was an audience of musicians and listeners alike who were scraping for new sounds once advanced technology made aggressive sampling of music possible.31 The sitar therefore was “dragged into the service of pop”32 and Ravi Shankar became a familiar face of this new sound for the west when “differences in musical form were no protection against the popular music world’s voracious appetite for unusual sounds.”33 Shankar’s audiences would majorly consist of jazz enthusiasts even before his techniques came to be learned and sometimes adopted without rigorous learning by Western musicians.34

From then on it was a dizzying vision of rapid cultural transactions as George Harrison began a liaison with the sitar and several short-lived pop experiments with Indian classical traditions began to find their way into the pop charts, much to the chagrin of Ravi Shankar himself who did not lay much store by the many theories of affinity between jazz and Hindustani music and thought they were overstated.35 For jazzists specifically, it was a logical move forward in their links with Islamic, Arabic, and Indian cultures.36 However, Shankar’s collaborations with jazz musicians, often outside the pop framework, set up a model for the Indo-Jazz genre, which might seem like a label under which something like Raga-Jazz Style fits comfortably.

The Shankar-Jaikishan album was not an international collaboration, but rather a group of musicians trained in Hindustani music playing with Goan jazz artists prominent in Bombay at the time. The commercial context within which a duo of Hindi film composers created an album outside of their popular film work was different from the ethos of Indo-Jazz. In Indo-Jazz, there was a move eastward as compositions tended to be set within rhythmic structures of Hindustani music37 while Raga-Jazz Style used Hindustani music melodically playing with jazz instruments within a tempo and rhythm already present in American Jazz. The album is a node in these connected histories of the two musics, but as an Indian recording of Indo-Jazz, at least at the time, it did not follow in the Indo-Jazz tradition.

Another argument which may be made to the same end concerns the market, about which Steven Feld wrote, “no matter how inspiring the musical creation, no matter how affirming its participatory dimension,” World music responds to globalization’s constant need for more markets, and for more marketable things.38 In fact, he sees world music as being complicit in the rise of “a kind of consumer-friendly multiculturalism.”39 This need for constant renewal of the musical commodity strangely works alongside what was mentioned earlier about aggressive innovation in jazz being a mode of disrupting the comfort and expectations of its white audiences. What comes to mind here is Marshall Berman’s best-known work All That Is Solid Melts into Air. In this, he finds the link between the market and aesthetic innovation. For Berman, “stability can only mean entropy, slow death, while our sense of progress and growth is the only way of knowing for sure that we are still alive.”40 Constant renewal means constant destruction and creation, and the unease of not being able to settle and not being able to stop the constant fleeting motion from one artistic innovation to another. The unease is what tells us that the art world is thriving, and the unease itself is driven by technological modernity within the framework of capital. If recording technology can drive a demand for new sounds to sample, then the collaborative aesthetic of world music and fusion is definitely taking place within the market.

Raga-Jazz Style diverges from this, in that it is commercially shrouded, almost hidden like a “collector’s item” amid the much more commercially popular film work of Shankar-Jaikishan. This is to say it did not follow in the tradition of Indo-Jazz fusion prominent at the time even when it comes to the logic of the market for which the music was being made. This still leaves for us the question, however, of what Raga-Jazz Style does to the traditions from which it does follow.

Diluting Together Raga and Jazz

Before the era of the phonograph, Hindustani classical musicians not only took inspiration from their listeners, but also improvised directly in response to their reactions. The exact sound and shape of the performance, then, was determined in part by the interaction of artist and audience.

—Mark Katz, Capturing Sound: How Technology has Changed Music

Katz’s comment on Hindustani music is a short tangent from his larger study of the phonograph and how modalities of listening changed with technological interventions in sound—and how creative practices of music changed along with it. While a protectionist attitude is thought to be characteristic of Hindustani and perhaps Carnatic traditions of Indian music, it has not kept the traditions from changing. Sarod played Ustad Amjad Ali Khan spoke about this in a recent interview:

In India, we blindly worship the convention whether it is religion or classical music. There is nothing wrong, and I also did it all my life. But tradition allows innovation. My father (Hafiz Ali Khan) who was my guru gave me liberty to go ahead with my thoughts and views.41

Such histories which are written about the onslaught of music-recording technologies, and the sea change that they brought about in the circulation and performance of music, often betray a sense of loss rather than one of anticipation. Whether we think of these changes as the dilution of a classical aesthetic or not, it is clear that technological innovation, a change in the modes of musical reception, and the changing marketability of classical sound charted the course from the courtly tradition to Raga-Jazz Style.

In a 1980 book on changes in the reception of Hindustani music in the twentieth century, Vim Van der Meer finds a link between the changing audience makeup and the slow disappearance of classical modes of performance such as Dhrupada. While clearly preferring the superior knowledge possessed by Dhrupada musicians, Meer finds that its esoteric content did not sit too well with urban audiences for whom a deep familiarity with idioms of classical music was not thought to be necessary to attend its performance.42 His analysis is fascinating in its indirect observations of audience behaviour, speaking of tea stalls outside the performance venue which would be filled up as soon as a Dhrupada singer began in the lineup of performances scheduled for the day.43 Urban middle-class audiences, distinctly knowable by how they spoke and attired themselves, would fill up both the rich social spaces of concert halls and also the cheaper open-air performances.44

Keeping this historical vignette in mind, what if we were to think about the change in the concept of the raga itself, much before it gets to Raga-Jazz Style? Meer observes that a raga was not meant to be a melodic frame. Rather, as a set of rules which were not designed to be understood literally, the emotive capability of a raga was meant to be housed within its intonation and its construction through successive phrases.45 Such a model of performance is only barely and loosely related to the improvisational model of jazz performance. McNeil goes as far as to suggest that there exists no word in any of the Indian languages which means exactly what improvisation means in English, preferring to see the boundary between fixed and unfixed material in a raga as a lot more ambiguous.46 As he points out the differences between improvisation in bebop jazz and unfolding in Hindustani music, he finds it difficult to come up with a fixed definition for ragas, and takes solace in metaphors, like the one comparing the raga to a seed which contains the possibility of the tree within it.47 It is therefore hard to come up with a suitable rubric with which we can compare the jazz and Hindustani elements of any of the eleven pieces in Raga-Jazz Style, even in terms of affect. There is some room to judge the emotive content of jazz through the spaces in which it was performed, and perhaps forward an analysis looking at the nightclub scene of small jazz venues where distracted listening has never been a problem and music is intimately part of the smoky sociability of the clubs. This cannot be compared to affect in Hindustani music without exploring at length its connection with the rasa theory, which suggests that certain ragas evoke particular and sustained moods within their listeners, and guide their performers.48 There is also the idea of performance-hours being associated with ragas, with some reserved for midnight, some other for dawn, and so on, which define the general mood of a raga. As Meer suggest, however, “the time-theory must be kept separate.” As such, “Its roots may be ritual or cosmological, but at present it is a mere custom.”49

We can but go back to Ravi Shankar’s experiences of performing Hindustani music for jazz audiences in the 1960s to find a certain disjunct in the artist’s expectations from the audience. Farrell writes that the sounds of India in conjunction with Western forms of music were viewed through a kind of beatitude.50 Therefore, performances such as Ravi Shankar’s were received through the “Western prism of a consumerist, quasi-mystical counter-culture, which had little or nothing to do with the music or its traditions.”51 Shankar himself, however, demanded a form of concentrated listening which was largely absent from his concert audiences. He was dismissive of the smoking, drinking, and drug-use which was a general characteristic of a lot of the concert venues he performed at, also perplexed at the relaxed sexual mores within which respect for the musician was put aside and music could become one part of the larger soundscape of the audience’s enjoyment.52 A remark by sitarist Nikhil Banerjee sits well here. When asked in an interview to comment on Ravi Shankar’s fusion experiments, he answered:

No comment, no comment. But I definitely didn’t like that duet with Mr. Yehudi Menuhin, East Meets West. No, I’ve heard Yehudi Menuhin many times; in Western music he’s a different giant, but when he’s playing some Indian music it is just like a child. For a stunt, it’s OK, but I really disagree, I don’t like this idea. You cannot mix up everything! It is not possible.53

Part of “You cannot mix up everything!” is what Ravi Shankar seems to have felt, though for different reasons. It must be said that his dismay is not meant to deny the presence of high seriousness in Western music, or even in American jazz specifically. Yet, it is also true that in the most popular jazz venues of the time, it was okay to be noisy.

But it was not as if concentrated listening had remained part of the marketable fabric of Hindustani music in India either, and this is where we can locate the “dilution” of a musical tradition which can then be incorporated into an album like Raga-Jazz Style. It is in the Hindi film industry that Hindustani music came to be incorporated into texts and visuals which, in a sense, was a logical continuation of the limiting of the raga to specific affective and melodic structures as discussed earlier. Jayson Beaster-Jones does a remarkable analysis of Shankar-Jaikishan’s filmic music in a section entitled “The Cosmopolitanism of Shankar-Jaikishan” in his book on Bollywood music.54 Commenting on their work in Raj Kapoor’s 1951 film, Awara, Jones notes that Shankar-Jaikishan were known for their classical roots upon which they innovated in their work for film. They had “one of the largest orchestras of the time, an innovative use of harmony and chromatic melodies (including some atonal moments reminiscent of the composer Igor Stravinsky), as well as the sounds and orchestration of Dixieland jazz,”55 a testament to their innovative outlook toward film music.

Their film compositions best exemplify the run up to Raga-Jazz Style in that their international influences were a result of their large orchestra including members from Goan dance troupes who used to perform in the nightclubs of Bombay. By the end of the 1960s, when the business of jazz clubs was no longer lucrative to the Western ethos of these Goan musicians, film music transformed from an occasional venture to a full-time career for them.56 This shift is telling because as Jones notes, “Many of these musicians had a limited understanding of the Hindi language—and often little interest in Hindi language films—but nevertheless collaborated on the composition of Hindi film songs and helped enhance their cosmopolitan repertoire.”57 There was more work to be found in the Hindi film industry than in jazz clubs.

I mentioned earlier that an album such as the one we are listening to here cannot be analyzed in the same fold as film music, because the commercial expectations of one are vastly different from the other. However, even the production of Raga-Jazz Style in 1968 comes through as a result of the lower cost of producing non-film music cassettes in the second half of the twentieth century. In fact, Jones sees Shankar-Jaikishan’s album at the beginning of a trend of Indi-pop music with which music companies tried to challenge the hegemony of film music, a movement which saw its heyday in the 1990s and continues today.58 It is still within a market that, at the time, was beginning to show the ability to support such work, that music like this is able to emerge. Once this music emerges in Raga-Jazz Style, with the promise of breaking free, it necessarily comes to be reinscribed within new rules and limited in new ways. For instance, what an interfusion with jazz does to Hindustani music is not that far off from what earlier encounters with colonial interpretation did to it. By itself, Hindustani music did not adhere to precise notational guidelines, nor could it be circumscribed within its textual descriptions. Its performance practice was always meant to be ineffable to the extent that it eludes a form of scientific control,59 while setting up controls upon which the musician can build. In saying this, I am looking at the same 1985 Nikhil Banerjee interview quoted earlier, where he talks about his discomfort with recording his music, and how he becomes “self-conscious” while recording.60 He is okay, however, with recording live-concerts, but the “minimum time should be about one hour.”61 And then there is Raga-Jazz Style, with eleven different ragas merged with jazz in album which is just over half-hour long. Obviously, this is an unfair comparison or critique to make, wherein lies the difficulty of thinking about connected histories.

We cannot say anymore that this album is a sound from nowhere. In fact, the complex and richly problematic histories leading up to the album show that it is only through an encounter with modernity, with coloniality, and with the market forces of popular music that Hindustani music comes to be incorporated and interwoven into the cosmopolitan ethos of fusion music for Shankar-Jaikishan in 1968. In its composition, the album has not severed itself from either of its constituent pasts, yet it is not the sum of its parts, and nor is it more than the sum of its parts. It might as well be unfettered, unmediated creativity. In spite of this instinct, what I have tried to do here is to offer an argument for historicity, and to say that Raga-Jazz Style does indeed come from somewhere.

Notes

- Giovanni Russonello, “Kadri Gopalnath, 69, Dies; Brought the Saxophone to Indian Music,” The New York Times, Oct. 31, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/31/arts/music/kadri-gopalnath-dead.html. ↩

- Veit Erlmann, Modernity, and the Global Imagination: South Africa and the West. (Oxford: University Press, 1999), 4. ↩

- Shankar-Jaikishan and Rais Khan, Raga-Jazz Style, His Masters’ Voice ECSD-2377, 1968, LP. ↩

- Shankar-Jaikishan, Raga Jazz Style, Deejay Audio, 2017, https://www.deejay.de/Shankar_Jaikishan_Raga_Jazz_Style_OTR-001_Vinyl__267563. ↩

- Shankar-Jaikishan, Raga Jazz Style. ↩

- Adrian McNeil, “Seed ideas and creativity in Hindustani raga music: beyondthe composition–improvisation dialectic,” Ethnomusicology Forum 26, no. 1 (2017): 120. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 119. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 119. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 124. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 124. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 124. ↩

- Laila Abu-Er-Rub et al. ed., “Introduction,” Engaging Transculturality: Concepts, Key Terms, Case Studies. (London: Routledge, 2019), xxix. ↩

- Peter Lavezolli, The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. (New York: Continuum, 2006), 1–3. ↩

- Martin Williams, The Jazz Tradition. (Oxford: University Press, 1993), 6, 40, 48, 218. ↩

- Arnold Shaw, Honkers and Shouters: The Golden Years of Rhythm and Blues. (New York: Macmillan, 1978), 3; Thomas Brothers, “Who’s on First, What’s Second, and Where Did They Come From? The Social and Musical Textures of Early Jazz,” Early Twentieth Century Brass Idioms: Art, Jazz, and Other Popular Traditions, ed. Howard T. Weiner (Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2009), 17. ↩

- Ajay Heble, Landing on the Wrong Note: Jazz, dissonance, and critical practice. (New York: Routledge: 2002), 15. ↩

- Heble, Landing on the Wrong Note, 59–60. ↩

- Herbie Hancock, “Herbie Hancock: The Ethics of Jazz | Mahindra Humanities Center,” YouTube video, posted by Harvard University, Feb. 13, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EPFXC3q1tTg. ↩

- Timothy Brennan, “World Music Does Not Exist,” Discourse 23, no. 1 (2001): 46. ↩

- Steven Feld, “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music,” Public Culture 12, no. 1 (2000): 167. ↩

- Gerry Farrell, Indian Music and the West. (Oxford: University Press, 1999), 202. ↩

- Joachim-Ernst Berendt, “Jazz Meets the World,” The World of Music 10, no. 3 (1968): 10. ↩

- Berendt, “Jazz Meets the World,” 11. ↩

- Berendt, “Jazz Meets the World,” 11. ↩

- Damon J. Phillips, Shaping Jazz: Cities, Labels, and the Global Emergence of an Art Form. (Princeton: University Press, 2013), 21. ↩

- Warren R Pinckney, Jr, “Jazz in India: Perspectives on Historical Development and Musical Acculturation,” Jazz Planet, ed. E. Taylor Atkins (Mississippi: University Press, 2003), 60. ↩

- Pinckney, Jr, “Jazz in India,” 61. ↩

- Pinckney, Jr, “Jazz in India,” 62. ↩

- Pinckney, Jr, “Jazz in India,” 62. ↩

- Jayson Beaster-Jones, Bollywood Sounds: The Cosmopolitan Mediations of Hindi Film Song. (Oxford: University Press, 2015), 77. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 169. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 169. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 172. ↩

- Berendt, “Jazz,” 9. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 177. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music,189. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 192. ↩

- Feld, “A Sweet Lullaby,” 167. ↩

- Feld, “A Sweet Lullaby,” 168. ↩

- Marshall Bermann, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air. (New York: Penguin, 1982), 95. ↩

- “Lengthy introduction of ‘Ragas’ can make them boring: Ustad Amjad Ali Khan,” Outlook, Jan. 27, 2019, https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/lengthy-introduction-of-ragas-can-make-them-boring-ustad-amjad-ali-khan/1466602. ↩

- Vim Van Der Meer, Hindustani Music in the 20th Century. (The Hague: Martinus NijhoffPublishers: 1980), 167–68. ↩

- Van Der Meer, Hindustani Music, 168. ↩

- Van Der Meer, Hindustani Music, 168. ↩

- Meer, Hindustani, 174. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 118. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 124. ↩

- McNeil, “Seed ideas,” 126. ↩

- Meer, Hindustani, 104. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 2. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 2. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 176. ↩

- Ira Landgarten, “Nikhil Banerjee Interview 11/9/85,” Raga Records, http://www.raga.com/interviews/207int1.html. ↩

- Beaster-Jones, Bollywood, 65–68. ↩

- Beaster-Jones, Bollywood, 66. ↩

- Beaster-Jones, Bollywood, 40. ↩

- Beaster-Jones, Bollywood, 76. ↩

- Beaster-Jones, Bollywood, 160. ↩

- Farrell, Indian Music, 2. ↩

- Lindgarten, “Nikhil Banerjee Interview.” ↩

- Lindgarten, “Nikhil Banerjee Interview.” ↩