[Content warning: This essay contains discussion on suicidal ideation, mania/depression, and in-depth ruminations on mental health. It contains no graphic descriptions. The section entitled “A Perilous Third Space” contains the majority of the discussion on suicidal ideation.]

Self as/and Mood Disorder

As human beings, each of us are constituted with a collage of identities. I am defined by my identity as a first-generation Asian American woman who grew up in the Mississippi Delta. I envision myself as a young academic working in interdisciplinary fields. I am a writer and artist—an introvert with a romantic appetite. Whether it be an exercise of ego or expression, we construe our identities to lend meaning to our lived experiences. That is why I also embrace my struggle of being disordered by mental health, with which I have used many words to describe (“suffer from,” “deal with,” “out of control,”) in attempts to helpfully name my cohabitation with bipolar disorder. My daily life involves constantly fencing off and regulating a condition that having control over is a survival necessity.

I have lived with bipolar II disorder (BP-II) since I was eighteen but was not properly diagnosed and medicated until I turned twenty-four. Bipolar disorder (BP) is a mood disorder and is frequently misdiagnosed as, or comorbid with, other mental health disorders, therefore complicating its treatment. Its defining feature is the mood-seesaw between depression and mania. Mania (or “hypo”-mania for BP-II) is defined by decreased need to sleep, euphoria, grandiose ideation, flight of ideas or speech, goal-driven activity, risk-taking behavior, and psychosis and hospitalization in some cases. My medication has been a regimen of anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers that treat a combination of anxiety, depression, and mania. Beyond this, lifestyle regulation—including sleep, diet, and exercise—are pivotal for staving off mental health instability. “Stability,” through these regimens, is key. But with all of the ways to manage a lifelong and “incurable” condition, sometimes circumstances still blindside you. Because while you can take melatonin, drink kale smoothies, and cut out the late night Malbec—and as you fastidiously work with psychiatrists, meditate, and philosophize about meaning—you could not anticipate that, in the middle of your first doctoral program year, you would have to gather your emotional and cerebral defenses for a pandemic that would exhaust every iota of coping.

From 2020 through 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic, a global health crisis unlike anything experienced in living memory, and the isolation of the lockdown and being confined to an apartment on the fourteenth floor of a high-rise building would compel me to think about my bipolar disorder in tandem with my lived environment in a new light. On one hand, space could connote safety and sterility; on the other, it signaled incarceration and seclusion. The pandemic’s lockdown over American households was meant to cleanly cordon off public and communal “sickness” away from domestic and intimate spaces.This experience made me realize that my long-standing clinical experience with bipolar disorder management followed an eerily similar logic of needing to constantly delineate “manic” versus “depressive” states-of-being for the very real necessity of maintaining my well-being. I noticed that adhering to such binary logics, especially in the experience of quarantine and bipolar disorder, helped me monitor those tricky mental states. I first believed that these logics of space were all compatible, but as the bipolar episodes worsened during the erratic winter of 2021—and I teetered on the razored edges of doing-good and not-doing-so-good—my belief of how mental health could be understood became more complex.

In this following reflection of my personal experience, I contemplate the idea of “third spaces,” where the slipperiness of sick vs. well; order vs. chaos; structural vs. individual; and real vs. imagined are exposed and reinvented. Third spaces became my metaphysical, intellectual, and material counter-site that gave me a way to survive those disordered days. While this is an intimate account of an individual experience of bipolar disorder, I also wonder how my personal experience might resonate with a greater collective desire to think about “well-being” beyond neatly packaged physiologies or definitions.

Lockdown: Ordering Space

A cliché—if not morbid—experience we all had was one of marinating, suffocating, wilding during the COVID-19 quarantine. Our bodies were in constant confrontation with danger and safety that has become attached to space, and the heightened familiarity or obsessive awareness of it.

Like many people during lockdown, I developed a strong desire to demarcate what was “safe” or not. Between the advice of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and my own levels of comfort for leaving the house, it became obvious to me that “space” was integral to our well-being. During this semester of graduate school, I lived alone in a sparsely but eclectically furnished, not-too-cramped, not-too-abundant apartment. My daily life, restricted to 800-square-feet of bedroom, kitchen, living room, bath, comfortably provided me with safety. When the unconscionable state of the world was reduced to this manageable breadth, it handed me back a sense of reality. Cordoned off from the outside virulence, the apartment became a functional vessel for that fantasy microcosm. It was only inside this air bubble that I could keep my bipolar disorder in check. This pursuit for normalcy manifested through my daily routines. On an average day, I wake up in the late morning and take my 600 mg of lithium and 250 mg of lamotrigine. I would wash my face in between, eat some yogurt and eggs, and sink onto the couch or the makeshift dining room work-space to read and write. The graduate student’s consciousness lived on Zoom: three hour seminars, meetings, and TA sections. Fellow students and professors lamented, and sympathized, and extended grace and caring each day. Venturing out for groceries or appointments felt precarious and illicit. Everything around me felt threatening.

During quarantine, I worked hard to regulate my medication and curb bad habits like drinking or staying up until 4:00 a.m in order to avoid the types of breakdowns I feared were nourished by my growing anxiety. I kept my spirits up with Zoom dates and dabbling in new interests with all the newfound free time we had. Graduate school and leisure were relegated to specific “zones” at home in order to maintain a verisimilitude of normal life. I went about the routines of this time in a kind of erratic haze devoid of contemplation as I was going through the motions to trudge through this school year. The constant variable I could rely on for well-being and daily consistency was the very organization of space between the inside and outside world—and also between each room and hall of my apartment into zones of work and leisure.

Disordering Space

It is common to think of space as the encapsulation of human-theorized boundaries. But space rendered as “mood” or “head”-space for me was equally real and important; transcribing bipolar disorder in inches of “depressive” and “manic” made the condition more manageable. The relationship between all these ideas of “spaces” in the months during lockdown began to stir up a sensation of “third space,” an idea which has been well theorized by scholars like Michel Foucault in his work on utopias and heterotopias, and Edward Soja in work on real, conceptual, and imagined spaces. While they worked on broad topics of cultural geography and institutional discourse, I wondered how conversations on mental illness could be tempered by similar ruminations.1 We can define “third” spaces as binaristic slippages between material and immaterial perceptions of space. We read COVID-19 spatialities—which are literally constituted by governmental policy—as the type of human-theorized space we are all doubtlessly familiar with. The abstract representations of space, such as that “mood” or “head”-space I manage mental illness through, is also still understood as “real” despite being “imagined.” When these two constitutions of space were experienced in tandem in my winter and spring, they were not as easily reconciled side-by-side.

As lockdown went on, the tedium of routine became suffocating, and the need to “perform” wellness felt contrived. Months passed slowly, quickly, then tediously to limbo again as the first spring passed. I can describe it as simply as numbness. The task of earning a PhD was suddenly Herculean—and it made me feel like a fraud, philosophizing over Zoom to a screenful of strangers in a seminar while lounging on the couch in pajamas and a hoodie. Graduate school made me feel like a failure in every possible way, and I couldn’t rest easy using the pandemic as an excuse for that lethargy. Gradually, dishes were abandoned and beds were left unmade. Whereas before I had created designated spaces for “work” on my dining room table, now books and computer cables spilled onto kitchen counters and coffee tables—even floors.

It is “easy” to feel depressed in the disorganization of an apartment when these living quarters become one’s entire existence and the outside world is interminably closed off. The apartment felt more and more oppressive for no understandable reason. Not even a hallway or curved lamp was neutral—whether it was the grating hum of the heating unit or lights that seemed to cast into a room a delusional normalcy of day and night. The physical sensation of a door handle or TV remote on my hand felt leaden. The recognizable lethargy was obvious when lying in a messy bedroom as a respite from social and academic obligation. The nightstand is a grim medicine cabinet, haphazardly organized and cold. My closet was an explosion of opened suitcases and broken hangers, and the seats of the living room sofa were sunk by hours of wine-night existential phone calls. I was bombarded by the unwanted awareness of too many small things with too much mental “fuzziness.” It reminded me of my mentally disordered college days, where my tiny dorm room functioned as the same kind of cozy, dark entrapment.

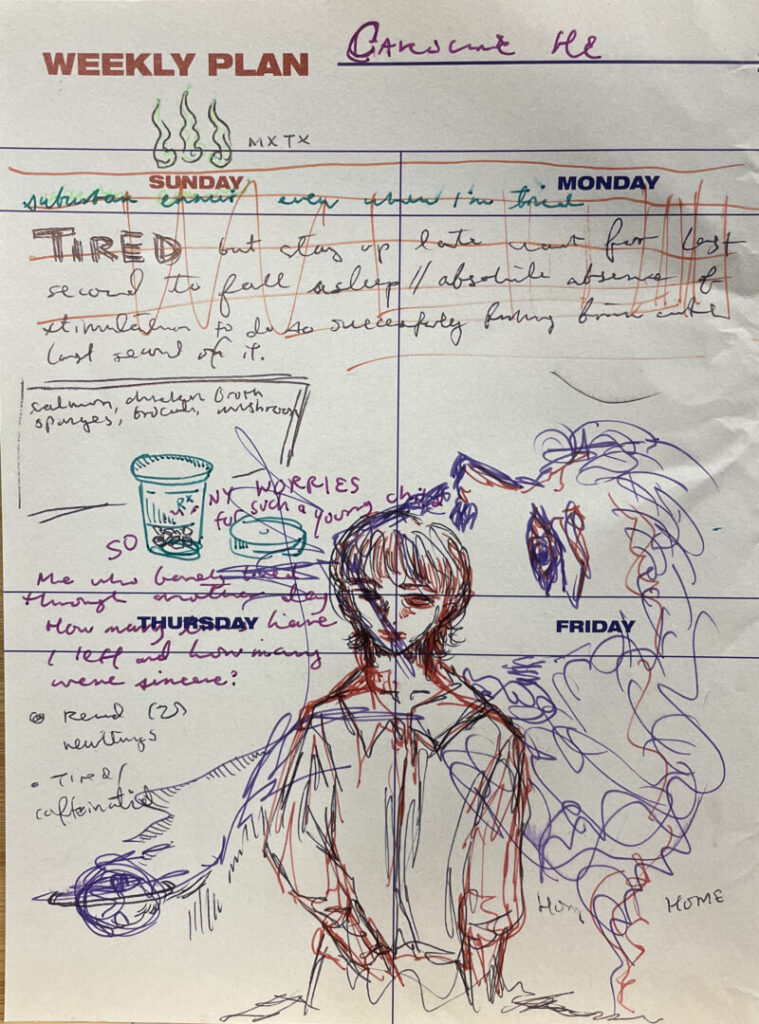

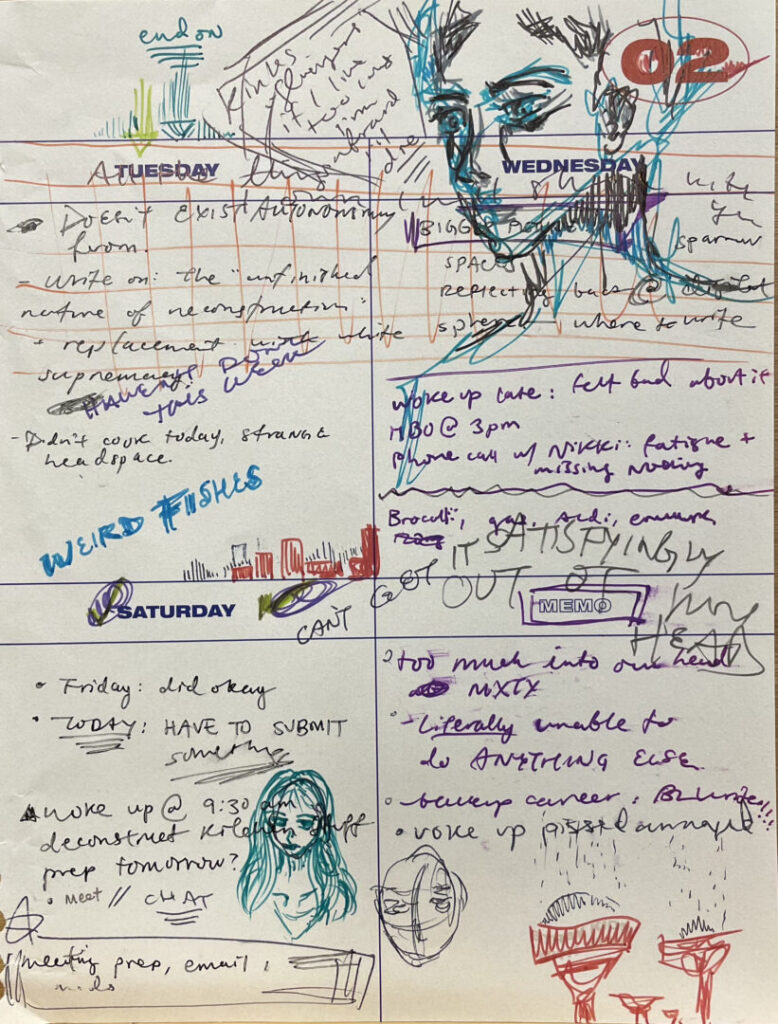

Mood States, Shapes, Spaces: Archive

I began to first find schisms of my spatialities in a daily planner I used to outline my schedules. I had a normal journal I used to write personal reflections in, but I inexplicably began to migrate to the planner for that purpose. Looking back on them now, it is interesting to note what sort of provenance is lost, especially as this type of template journal—part of just a K-pop holiday gift set—was undated to begin with. The understandings of these entries become reinterpreted in this new temporal moment of reevaluation.

Today, when I rifle through these old paper entries, I note that they are not a clean and reliable record of any particular mood-states. If anything, seeing the messiness of neatly boxed days of the months helped me gain a perceptual clarity of how I was subjectively experiencing these spaces I dwelled in during quarantine. And retrospectively, I realize that the specific ways I was organizing space as well-being was not neatly contained at all.

In the journal space, I deconstructed the neatly marked spaces of my apartment, the world, and my interiority. These deconstructions were cathartic. And, despite its chaos, it somehow made my tasks and passing days more knowable—the more disordered it became, the more I felt like the multiple filing cabinets in my brain and body were being consolidated. In organization, I see madness; in madness, I see organization.

The depressive side of bipolar disorder, unlike its euphoric cousin, is often what people seek psychiatric help for when the “good feelings” of mania subside. During depressive states, I spoke many times with my psychiatrist about medications as my moods fell flat. As the more calm and predictable state of bipolar disorder, my depression nestles like a polymer into the cracks of being buzzed or blank. In some ways, it is the easier side to manage, but the hardest to “fix”— and the most agonizing. Yet, as hopeless as this all was, the depressive cycle was familiar to me. While the unique circumstances of COVID-19 lockdown exacerbated the onset and severity, I knew that as long as I endeavored to upkeep my routines, that this episode would pass.

The manic body is shared with the depressed one. While depressive moods were most prevalent and lingering, in the intermission of darkness and gloom, I arose like a glittery phoenix in the orange juice skies. Sometimes it feels like an obvious switch turned on, and other times it is near impossible to determine when the rupture happened. Despite many years of maintenance and knowledge, the onset euphoria of it still deludes me into believing that this remarkable instant is a permanent new lease on life.

My physical sensation of mania includes a tugging at my eyes, a throttling rattle, and a background hum of suspense. It feels like when the lingering flashes and music from a loud concert follow you home. When I first slipped into a manic cycle during lockdown, the apartment came alive slowly, as if the previous oppressive hums and dings began encouraging me instead by blasting me out of bed. I arose from sleep each morning a little bit less weighed down by depressive thoughts, finding it easier to sleep five hours a night and feel pumped the next day. Slowly came the mad-dash marathon of conversations, waking hours, drinking, eating, self-aggrandizing. In past manic episodes, I used to walk miles in the snow at midnight and smoke cigarettes. In this apartment, the bedroom, once that place of respite, became one of un-sleep; what was once a tepid apartment of quarantine became one that could not contain the snap crackle pop of mania. Usually, people around you can see these symptoms, but during COVID-19, social spaces of support were confined to neatly-boxed Zoom windows.

I draw attention to the tenuous and ineffective interpretations of space that were meant to demarcate the lines of where sickness and wellness persisted. In my experience in this short span of quarantine time, my dual mood states competed and worked to dismantle each other or meld together. The scariest part of this time for me was when mania drove me to feel disconnected from reality and disconnected from my body and impulse control. When you lose that grounded-ness in the neat delineation of types of spaces is perhaps where meditating on space is least cathartic.

A Perilous Third Space

[Content Warning: This section discusses non-graphic suicidal ideation.]

I spoke of kitchen counters, dining tables, lamps, nightstands, and oppressive hallways and rooms. I talked about parsing out mania and depression as a spectrum of mental states, still physiologically treated and defined by its definitive binaries. I also spoke of the slippery organizations of all these boundaries: in this coda, I no longer distinguish between mood states. One more space, which I morbidly call the final frontier, is the last third space I want to reflect upon.

In months, perhaps a year’s time after tumbling through mood states and moments of respite, I developed a compulsive attraction to the most uncomfortable space of this quarantine apartment, beyond the warm physical walls that blueprinted my daily routine. Or rather, a unique space outside of it. In pandemic-speak, the “outside” world came to be equated with a definitive horror that can be negated by the indoors. Yet, the dual side of “outside” became a desired place of escape.

On the fourteenth floor, mine is a wrap-around railing with two deck chairs and a wooden white table; standing there, you face the western sky and are greeted with a wide expanse of forest. The balcony, hovering above the air and connected to my apartment, is horror and liberation melded together in a morbid and fatal sense—“release” and “relief.” In the biting cold wind of winter, the crisp air represents primordial and unadulterated freedom; looking up at the blue sky evokes the grandeur of space and simultaneously its absence. As one must exit the apartment to step onto it, the balcony has come to represent the “outside” world beyond the safety of quarantined boundaries. It is the sensation of freedom attached to a fear of straying too far into a horrifying world—the promise of a breath of fresh air mixed with worries of viral contamination. This is a world uncontained by walls—and that there is sweet ground that so easily ends existence. It was easy for me to see a correlation between depression and tall buildings—a thought I will leave here incomplete. But the short, delicious manic flare-up painted the balcony with newfound pizazz, soar—a pavement of anticipation that welcomes release. The way I began to read this space in the throes of mania became completely different. It paralleled how I compartmentalized space into safe physical and psychological zones—and it echoed the very breakdown of those boundaries by offering a world of different logics and of contradictory yet coexisting realities.

This third space is a space not quite inside or quite outside, not quite firmly a space of safety or danger. Not quite a respite or crisis of slow, fast, compact, and frenetic manic depressive states. It offered the safety of comfort, order, and wellness—and it was also a necessary relief from it. Thinking back, I do not think I was in real danger of harming myself. My preoccupation with that balcony was more of an analogy for making sense of scrambled spatiality and temporality as a global health crisis raged on outside. All while my privileged sanctuary posed “serene” personal reckoning with mental health. I stress the difficulty in both upholding and deconstructing notions of boundaries—as the events of these months have shown how important materially and abstractly constructed spaces are to all types of survival. But, I at least think invigorating imaginaries lie in third-ing spaces and exploring such existential-physical-intellectual slippages.

The experience of all these mental states blurring together was reflected in the very process of writing this essay, particularly toward this very last section. The somewhat disorderliness of it reflected an impulse to write about my bipolar disorder beyond binaristic or narrative structures. In reveling in and playing with this messiness, I let a lot of concrete understanding and clarity linger in the margins. And perhaps that is most fitting. I lean into what La Marr Jurelle Bruce discussed in his book How To Go Mad Without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Radical Creativity, meditating with new conceptions of “madness,” and spaces where madness can be claimed—specifically in contexts that defy social norms.2 If taboo topics like suicide and mental health can be bridged with conversations on intimate spaces and how they are linked to a collective experience, such as the inconceivable tragedies of the pandemic, then reflecting on madness and the experience of the pandemic together may offer “third spaces” of renewal previously unthought of.

Reflection: Potentialities of Space in Healing

I hope my reflection on “space” and the possibilities of different such spaces comes across as an empathetic one. Loosely drawing from some thinkers on space and time, I offer individual experiences of mental health in parallel with collective global health crises disasters, starting from just this one tale inside a single apartment complex. Third spaces are ones that dwell in the margins and complicate the production of perfect boundaries and binaries—inclinations that can be counterproductive to other possibilities of healing, restoration, and intimacy.

By late spring and summer 2021, the loosening up of COVID-19 restrictions interjected some normalcy back into my life. The freedom that accompanied it doubtlessly freed some people (like me) yet put more vulnerable communities at risk. It is a tension still being negotiated. This essay tries to add to a bigger conversation on how we rely on definitions to encapsulate some material reality of mental health. Our experiences cannot be condensed into “knowable” handbooks and protocols. And we cannot skimp on the conversation around social models of disability and larger power structures that define bodies as ill or necrotic—whether that be born from a pandemic or discussions on mental health. As Soja and Foucault have suggested, third spaces and heterotopias are inherently counter-sites. They call for a public and collectivist discussion of space—an ethos I see emerge also in communal discussions of mental health that move beyond individual spheres of intimacy.

The unfortunate side effect of post-manic/depressive haze, especially now years later, helped me accept that repair does not have to equal a clear-cut mastery over a mental condition; it can be a slow celebration of that learning process itself. Hell, even how I chose to structure this meditation is bound to unsatisfying headings that continue to confine my narrative too neatly. Nonetheless, my own meditation is exactly that: “my own.” I could not endeavor here to explore the totality of COVID-19’s effect on collective experiences of mental illness. This piece is not written to offer any neatly packaged analysis or conclusion beyond one of presenting what is one account of grappling with mental illness in the solitary, quiet, alienated confinement in an anxious COVID-19 world. I think of the “healthier” place in my mental health journey that I reside in today. The experience of that winter helped me embrace tensions in all areas of my life—instead of running away from them.

Notes

- Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 22–27, https://doi.org/10.2307/464648; Edward W. Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1996). ↩

- La Marr Jurelle Bruce, How To Go Mad Without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Radical Creativity (Durham: Duke University Press). ↩