Essay Map

Legend

The purpose of the essay map is to provide guidance for the layout of this essay. The structure of the essay is outlined above. We created a glossary to provide readers with our understanding and use of frequent terminology. This is a feature added for reader accessibility.

When we draw directly from our experiences, we provide a subheading to indicate whose experience is being shared.

A note on wording: within this essay, the “COVID-19 pandemic” will be addressed as “the pandemic” unless otherwise noted. We do not use the term “BIPOC” (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), which is commonly used in the United States. As this essay emerges from the UK context, we use the term “People of Color” or “POC.” One of the commonly used terms for POC in the UK is “BAME” (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic); however, we do not use this term. From Denise’s experience as a British East Asian person, the “Asian” within BAME is often equated with Asians who are not “yellow,” and the term has, therefore, not been representative of her experience, particularly within the pandemic.1

We originally wrote the first version of this essay in late 2021, and much has changed since then. However, we do not reflect on these changes, as the essay’s intent is to capture our experience at that time and the process of publication has been extended due to further challenges we have both faced.

1. Glossary

Vulnerability

Political theorists and gender studies scholars looking at grief and COVID-19, Zuzana Maďarová, Pavol Hardoš, and Alexandra Ostertágová explain that some lives are made more vulnerable and at risk under capitalism, which exacerbates pervasive inequalities and oppressions.2 We use this understanding as a starting point to explore our own experiences of vulnerability during the pandemic.

Ungrievability

If someone’s life is grievable, all possible measures are taken to preserve, honor, and respect such a life, and there is the acknowledgement of loss; ungrievable lives are not considered by those in power, which, as Maďarová, Hardoš, and Ostertágová discuss, is reflected in wider society.3 We felt that the ways in which those in power made decisions that lead to the preventable deaths of POC and disabled people were well encapsulated by this concept.

Embodied Belonging

We view embodied belonging as resilience. Medical anthropologists Mattes and Lang offer that finding or creating spaces and cultivating the feeling of agency and autonomy for ourselves and our bodies is a radical and often necessary act when navigating hostile environments.4

Access Intimacy

Disability justice activist Mia Mingus coined the term access intimacy and described it as: “knowing that someone else is with me in this mess.”5 This quote from Mia Mingus’ essay stood out to us both as it resonated with how we understand our friendship. We are together in navigating life’s challenges in a world that is often inaccessible.6

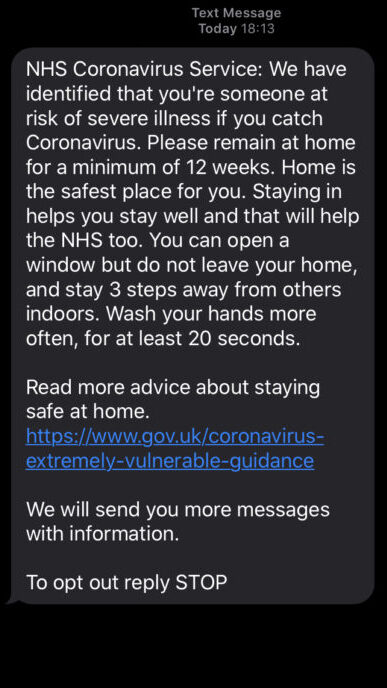

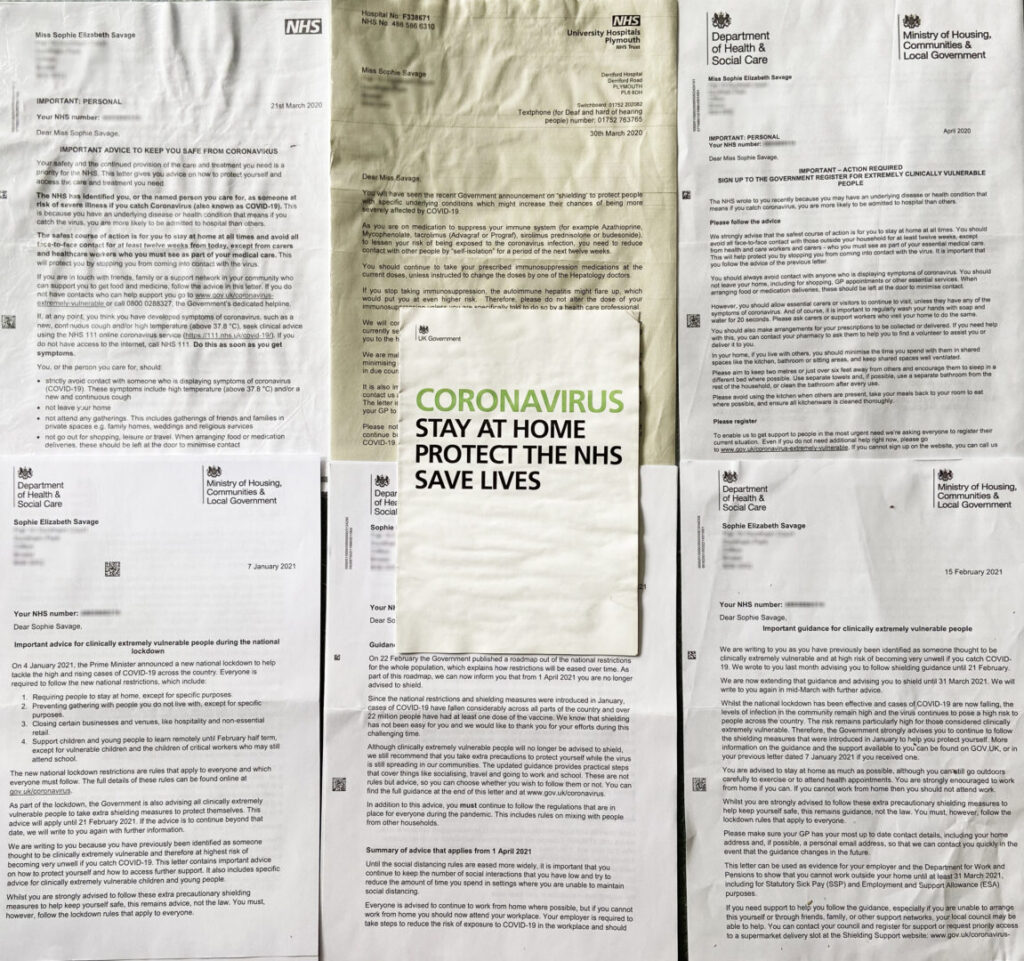

Clinically Extremely Vulnerable (CEV)

The CEV group was a term coined by the UK government during the pandemic to describe those with reduced immune systems, for example, due to organ transplants, or those with specific cancers or severe respiratory conditions.7 We use this term as Sophie was labelled as such.

Shielding

The UK Shielding program directed CEV people, like Sophie, to follow strict guidance regarding their behaviours, for example:8

- Do not leave your home

- Do not attend any gatherings

- Do not go out for shopping, leisure or travel

- Keep in touch using remote technology

- Regularly wash your hands with soap and water

- Regular medication must be delivered

- Healthcare appointments will be provided by phone, email, or online

- Planned hospital appointments will be cancelled or postponed

2. Introduction

This essay has two authors, Denise and Sophie, both belonging to communities disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Denise is from Hong Kong (HK) with chronic eczema and experience of the 2003 SARS pandemic.9 Sophie is from England and was classified as CEV due to being immunosuppressed following a liver transplant. We first met when Sophie gave a lecture to music therapy students about Disabled Children’s Childhood Studies.10 Later and through mutual friends, Denise arrived at Sophie’s thirtieth birthday party, where our conversation on identity and belonging began; we have been close friends ever since. Our homes are in Bristol in the Southwest of England.

The UK government approached the pandemic by continually prioritising the economy over safety, heralding the importance of individual choice over collective safety. This led to increased anxiety for us both, making it difficult to navigate public spaces.11 For Sophie, this has meant continual isolation and a lack of trust in the state; for Denise, this has meant a continual threat to safety and further reinforcing a sense of non-belonging. Within this neoliberal undercurrent of a lack of care, some have marched for the right to not wear a mask or engage with the vaccine programme,12 but some of us are marching, or are not able to march, for our rights to life.13

This work began as a paper presentation for the 2021 Association for the Psychoanalysis of Culture and Society online conference. The suggested conference themes, in particular, “working through COVID-19,” “ableism and the lack of recognizing a ‘non-able’ body,” and “migration and traumatic political reenactment,” resonated with our shared and individual experience of the pandemic. This early version began to explore some of the concepts mentioned in this essay, however, it felt important to expand and deepen our understanding. When we received the call for papers for this special section, it felt like an important opportunity to craft our narratives and contribute to a vibrant tapestry of crip experiences of the pandemic.

In this essay, we discuss vulnerability, ungrievability, and embodied belonging in relation to our experiences.14 By exploring the ways in which we are made vulnerable and ungrievable through systematic oppression and a pervasive sense of non-belonging, we use the concept of access intimacy to discuss our resistance and to demonstrate how we have navigated and understood the pandemic together.15 Advocating for the importance of friendship and prioritising time for practising care is at the core of our message.

Drawing on our lived experiences of ableism and racism, we reflect on internal and external processes of othering. We acknowledge our privilege of being able to stay safely in our homes, access our strong networks of care, and write this essay together. The experiences we share are painful and difficult. Being close friends, we spoke openly and honestly as we wrote, mining deep and ongoing trauma, and processing it together.

2a. Denise

My skin, and the reactions to and of my skin, are the focus of my narrative. Living with chronic eczema and being an East-Asian woman in the UK have shaped the ways I navigate life here. Drawing on my experience of eczema, I was motivated to study psychology and chose to migrate to the UK a decade ago. However, transitioning from being an ethnic majority in HK to navigating what it means to be a minority in the UK was a difficult process.

When COVID-19 became widespread in the UK, my memories of living through the 2003 SARS pandemic as a child resurfaced, leading to re-traumatisation.16 I remember the militant approach to wearing masks, daily temperature checks, and the overwhelming smell of bleach over surfaces which attacked my nose, even through the mask. The bleach imprinted a strong sensory impression and shaped my understanding of the severity of the virus.

At the beginning of the first lockdown in March 2020, I initially experienced a freeze response as I was unable to fight or flee.17 On top of wearing a mask, I wore cotton gloves because of my eczema. I consistently found myself facing racial discrimination and microaggressions in the UK because I am Asian. As the pandemic unfolded, this feeling of otherness increased. Countries in the West mocked Asians for wearing masks. Advice from the World Health Organisation described wearing face-coverings as a “cultural practice” and not scientifically proven, which was echoed by the university where I was enrolled.18

2b. Sophie

Exclusion forms the focus of my narrative, as my immune system struggles with daily life. I was born with liver disease and had a transplant as a child, meaning I was often unwell, necessitating long hospital stays. Acute illness led to periods of clinical isolation in hospital, where medical staff would only enter infrequently to take observations and provide medication or food. I have always loved learning, and I found refuge in the hospital’s schoolroom among my diverse peers navigating their own health challenges. At school, however, I was relentlessly bullied; my low attendance, appearance, and daily life were unrelatable. I had thin limbs, a swollen abdomen, and jaundiced skin; I fitted the role of “alien” whilst being alienated. The children’s liver ward felt like a place of belonging, but to belong in an institution of chronically ill and dying children with a frequent bed turnover did not bode well for establishing friendships.

This mode of being inside and outside of collective experience is familiar. At the beginning of the pandemic, I was included in the national shielding programme. Shielding differs from clinical isolation; I was not unwell and my body thrives without the daily assault on my immune system. For the first time in my life, I managed over two years without an inpatient hospital admission. Observing the growing numbers of those ill and dying through the media echoed my childhood, surrounded by children fighting for their lives.

The reality for many disabled people and shielders was remarkably different to others navigating the pandemic. I noticed some people’s choices correlated to those becoming unwell and dying, as they boasted on social media that they were “just getting on with their lives.” Few acknowledged or connected with my reality. With the growing threat to my life, I struggled with understanding those choices. I was becoming less easy to understand and understanding less.

2c. Together

We needed each other’s support to undertake this work, mirroring our need for each other throughout the pandemic. We argue that the intersectional and empathetic connection between us both represents the importance of care, empathy, and love needed to thrive during the pandemic. We demonstrate a deep reverence for each other and our trek through hostile environments, providing a counterpoint to the neoliberal structures of oppression as we find ways to live, create, and flourish.

3. Navigating the Pandemic

Together, we created our own robust support network, as we cared for and were simultaneously supported by our new chosen family here in Bristol. Our friendship is one which practices the ethos of access intimacy with continual communication, covering all realms of caregiving, working against systems of oppression, supporting each other’s professional careers, and collaborating creatively on shared projects such as the co-production of this essay.19 With access intimacy, friendship can unfold through speaking in shorthand and sharing knowing looks, which can transcend the exhausting process of trying to make yourself understood, heard, and acknowledged. We feel that the way access intimacy is perceived externally disrupts societal expectations of friendship. As we consider our relationship, we believe that friendships need to generally be held in higher regard. What we can communicate in a look could take an essay to explain, as we are demonstrating here.

We already understand each other in a deep way, so we often start our conversations at a more advanced level. Fuck the small talk, how’s your sense of self in the face of hatred or potential death is where we started. This is not specific to the pandemic. We have always been this way since Denise arrived at Sophie’s party and began to unpack Denise’s identity crisis over birthday cake.

3a. Sophie

As an immunosuppressed person who has had a liver transplant, I have always had a complicated sense of embodiment and belonging, one which is shared among other transplant recipients, as my body is a container for another’s organ that is always “other.”20 Both theoretically and biomedically, transplanted organs cannot assimilate to become “self” material, as the donor’s DNA remains.21 For me, any distinct boundaries between the self and other within my body have been permanently permeated and the clear distinctions of life and death have been subsumed. The non-self material I hold inside my body brings the possibility of survival for us both, but it also represents an immunological conflict, as my immune system battles the non-self organ, bringing the potential of a more lasting death for us both. Transplantation provides a permanent opening for housing difference, arguing for the concept of an intercorporality or hybridity. When post-human philosopher Shildrick argues that hybrids challenge normativity, I feel that this speaks deeply to my eternal preoccupation with asking “why,” particularly in consideration of established tropes surrounding common discourses of transplantation, namely spare parts surgery or the gift of life.22 This is echoed in my journeys navigating healthcare systems and in my professional life as a sociologist: challenging norms and taking a critical position is a way of being.

The internal experience of othering I have described is also reflected externally. As I was included in the national shielding programme, I received regular communications from society and the state, reminding me of how vulnerable I was and how important it was to stay inside. From December 2019, when the pandemic was more prevalent in Asia, I was already acutely aware that I might not survive. Although I felt my vulnerability and a lack of understanding from those around me from an early age, this is the first time that this was happening on a global scale. The national figures of disabled people dying due to COVID-19 really pressed into me, as I contemplated how society fails to demonstrate the value of my life whilst being reminded of the likelihood of my death.

Dominic Cummings, former advisor to the former UK Prime Minister, published photos of a whiteboard in 2021, which depicts an early plan for the governmental response to the pandemic. On it appeared the chilling question: who do we not save?23 To answer this question, the Office for National Statistics published data in November 2020, which showed that 59 percent of the people who have died of COVID-19 were disabled people.24

Being diagnosed with childhood liver disease from an early age has meant I have always had an awareness of my own mortality, however, the reality of the pandemic is quite different. Remembering the children I met and made friends with in hospital, how we learnt together in the schoolroom, played and shared meal times at the dinner table, swapping gameboy games before lights out. Many of my young comrades who, like me, were adorned with a wristband showing our hospital number, were lost. Families were devastated and those caring for us were worn down. The ongoing loss increases pressure to improve treatments and services, so more of us could have the opportunity of enjoying our childhoods and what might come after. When I read the statistics mentioned above of those dying in the pandemic due to the callous, unfeeling, and eugenicist approach from the UK government, I returned to that space of being a child in hospital, surrounded by desperate families and incredible health workers, and I despaired. The pain of losing these strangers discussed on the news was felt constantly. I spent my life grieving the children from my ward and dealing with feelings of guilt as to why I did not join them in death at a young age. Therefore I do not feel I can separate myself from these statistics, these lives that were lives, that were lived, that did happen, and that each and everyone are important and vital. Luck and privilege stand between myself and others, and I am cognisant of this every day. On one hand, the government sends messages that you are considered CEV and told to stay home and stay safe. Yet, disabled people are not always able to get access to essential care and supplies, with serious consequences demonstrated in the growing numbers of those who have sadly died from COVID. These losses are reduced to numbers, an echo of the ways in which the system recognizes us once again. The pain of this reframing of these people as ungrievable is too hard to bear.

Disabled poet and activist Karl Knights has described this disproportionate impact on the disabled population as the “daily eugenics” which he feels is becoming sickeningly “normalised.”25 During this time, the UK government imposed “Do Not Resuscitate” (DNR) measures on some disabled people; this meant they were not to be resuscitated even if there was the choice to do so, prioritising some lives over others.26

Speaking with Denise about how she feels about these DNR measures as my close friend, she reflects how horrifyingly unfair it is and how such an inhumane process was even considered. If I had died in the first wave of the pandemic when these measures were in action, Denise tells me that she can imagine feeling rage, injustice, and deep grief. In considering how my life is valued, how I would be missed, how I do matter, how I am a part of a family, a chosen family, friendships, communities, and a workplace. I do exist, I am loved, and I am grievable. To consider how many people—whose friends and loved ones feel the same as Denise feels about me—have lost their friends, weighs heavily and has affected us both profoundly. Applying DNR measures to disabled people, for most people, is truly unthinkable.

In regards to what Knights describes as “daily eugenics,”27 the application of DNR’s in combination with loss of access to essential care, long waitlists for necessary treatment, digital exclusion and social isolation, the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on disabled people is clearly argued.28

During shielding, few people acknowledged my reality, and others would frame my cautions around safety and strict adherence to guidelines as proof of paranoia and anxiety. I am an anxious person, so it is easy to link my mental health with my behaviour in all realms of life. There are many examples whereby people have framed my actions in relation to the pandemic akin to a narrative of anxiety rather than physical safety and response to a life-threatening contagion. Perhaps it is easier to gaslight a disabled person as hysterical rather than acknowledging how ableism devalues my life and places me amongst the ungrievable masses.

To be made vulnerable and ungrievable demonstrates the ways that capitalism and austerity measures marginalized lives, as someone’s “value” is based upon productivity and how individuals can service capitalism.29 The pressure to perform is paramount; a person’s value is based on their productivity and those with bodies built for endurance are prioritised over all others.30

In my attempts to navigate the dominant discourse of “uberperformance”31 and the ways in which disabled people have been made vulnerable during the pandemic, I found myself working long hours to my own detriment to demonstrate that I have value. I acknowledge here the ills of internalized capitalism as I equate my sense of self with what I am worth to the systems I serve, balancing my existence on my productivity. This immoral calculation has haunted me since birth as I have, since I was a child, had a growing awareness of the cost of my medical care and this sense of owing the state an unrepayable debt is pervasive. I can logically critique the systems of oppression and their impression on my well-being, however, there is seemingly little time to process all that is happening. Through exhaustion, I continue.

3b. Denise

During the pandemic, HK was undergoing a period of civil unrest, and the National Security Law brought in greater punitive measures around freedom of expression.32 There is a stark contrast between the reality of HK to what is reported in the international media as this period has highlighted differing views on authoritarian rule and neoliberalism.33 The reality was that freedoms were being revoked under the guise of COVID-19 safety, including the right to protest, gather, censorship and obliteration of democracy as political parties with an oppositional stance have been arrested, making HK a one-party state.34 From the historical context of British rule and the current authoritarian regime from China, people from HK have been dealing with an existential crisis of national identity.35

This crisis of identity is one I hold. In the UK, I have been undergoing a process of establishing my identity as a British East-Asian citizen: I am both from HK and British. In public spaces here, I am subjected to racism, where my identity is rejected. Conversely, HK is no longer the place that I know, nor can I return to, due to the pandemic. There is fragmentation in both places I call home, making it difficult to find belonging. Having struggled with this identity crisis for years, I began seeking others with similar narratives, who share my pains and feel out of place. I found grounding and a sense of self in developing practices that allow me to celebrate my culture, mainly in food and traditions surrounding different festivals. In this period, I lost some connections, but I also found new friends and joined networks of people navigating similar journeys. Connections old and new along with work in therapy allowed me the space to grieve for the loss of one of my homes and a pivotal sense of self.

The complexity of racism in the UK gives rise to self-doubt when experiencing anti-Asian hate.36 Within the UK, the racism, violence, oppression and othering directed at the East-Asian population is hidden; there is a lack of representation and connection to the lived experience of East-Asians residing in the UK, regardless of whether the UK is their country of origin.37 Platforms for discussion of anti-Asian hate crimes have increased since the beginning of the pandemic, providing space for working through people’s experiences of being East-Asian in the UK.38

Coming from a majority population in HK and moving to the UK as an adult, I recognized both the systems of oppression within society and racial-hate directed towards me, particularly in public spaces. As I grew up in a society where I am of the dominant race, initially I lacked the vocabulary to articulate and process my experience. I am acutely aware of the colonial history and prevailing racial discrimination from the East Asian population towards other POC. However, I grew to recognize my vulnerability in the UK and the importance of sharing my experiences for fear of my own safety.

There was a disproportionate representation of East-Asian faces within the media for general updates about the pandemic unrelated to the pandemic situation in Asia, reinforcing the idea that East-Asian people were the face of the virus and potential carriers.39 Fang and Liu discuss how terminology such as “Chinese Virus” was used often by people in positions of power, which again reinforced and fueled anti-Asian hate crimes.40 Reflecting on the growing vulnerability to hate crime at the start of the pandemic, Fang and Liu refer to incidences of feeling watched and changing their behavior, so they did not enter public spaces unaccompanied.41 They mentioned a particular incidence of being spat at, which is all the more horrifying in the context of COVID and how it is spread.42

Throughout the pandemic, I have found myself conflated with the virus. My personality and professional identities became irrelevant. When in public spaces with my face mask on, I have experienced different degrees of invasive surveillance, from peripheral observations to overt staring, distancing and tutting, making public spaces hostile. COVID-19 has been assimilated into the ensemble of racist discourse; though previously I would be called acutely racist words relating to my ethnicity in public spaces, and although verbal abuse is a common occurrence more generally for women, this intensified during the first UK lockdown. One weekend in the first month of the March 2020 lockdown, my white male partner and I were going for our state-mandated daily walk on the local high street when a car of two or three young white men drove past. They kept driving when they passed us, as the man on the front passenger seat rolled down the window, and yelled “corona corona” whilst leaning out of the window, moving his arm and fist in a circular motion to get my attention. This cowardly public attack was the first case of racial aggression towards me being related directly to COVID-19 and this frames my experience of societal perceptions of East Asians living in the UK at the start of the pandemic.

Within my care network here in the UK, no one else understood the first month of the pandemic the same way Sophie did. Sophie introduced me to Nini Fang and her work as Sophie had recognized the potential for its resonance with my experience.43 This introduction invoked a powerful response both personally and professionally, leading to further reflections in other spaces, including a music therapy conference presentation and subsequent podcast.44 Although Sophie is not Asian, there is a similar sense of being othered, reduced, and made vulnerable that cuts through our differences, whilst still learning from each other. I continually updated Sophie about what was happening in HK because we already had this instantaneous understanding of each other’s experiences. Without a potential fear of othering, prejudice, or discrimination, there was no need to foreground or preface my triggered state regarding my previous experiences of living through SARS, I knew Sophie got it.

Although I was following similar practices as Fang and Liu mentioned, by avoiding being in public spaces unaccompanied, I still experienced hate crimes.45 I was reduced to an embodiment of the virus, and I was to be blamed, avoided, and shunned. Even within virtual spaces, I faced discrimination as I encountered “microaggressions.” During an online seminar for music therapy trainees during the early months of the pandemic, an educational professional described another trainee’s zoom name as “exotic,” and jokingly asked if there was anyone “foreign” here. As it happened, I was the only trainee present who was not white and not born in England. What compounded the hurt at that time was that a “friend” on my course did not try to understand my experience as it was happening, which furthered the othering. This experience highlighted how virtual spaces exposed the undercurrent of prejudice that is always present in public spaces.46

As I live in a body with an inflammatory reaction to environmental factors, this means constant adaptation. Having an Asian body in an environment whilst being equated with “the virus” has also triggered ongoing adaptation. My sense of embodied belonging fluctuates due to the severity of inflammation which is exacerbated by stress, also fueled by the ongoing identity crisis from my fractured homes. With the continuous pandemic challenges mentioned above, there is a pervasive sense of non-belonging in the ways in which I am perceived in public spaces and how I exist in my body.

My understanding of eczema is that it is an immunological attack on myself, which complicates my feelings when experiencing racism. I am attacked by both the racist reactions from other people attacking me for my skin colour, but also my body is attacking me through inflammation and pain. Racism is never acceptable but the ongoing inflammation, breaking, bleeding, and pain due to eczema further contributes to the ways in which I am made vulnerable. Skin is the body’s barrier and one of the ways we can interact with the outside world; therefore, this immunological response to the environment, which I have to cope with daily, is magnified by the experience of racism. Being Asian while having eczema during a pandemic is an intense and dynamic experience of othering.

This reflection on internal and external processes is felt by us both and demonstrates how profoundly the concept of access intimacy characterizes our relationship: we are truly with each other in all this mess.47 As racism and ableism increase stress and othering, this depletes our well-being and sense of self. Despite belonging to various minoritized populations, our intersectional experiences of the internal and external othering are not necessarily universal, and the connection between the bodily reaction to the outside, whilst navigating immunological conflict provides anchors for a rich understanding and empathy of each other. Working against othering to create a sense of belonging and value for us both.

4. Together We Flourish

Our previous vignettes have focused on our individual experiences and the challenges we have faced regarding ableism, racism and othering, and we began discussing our mutual understanding of navigating the pandemic. For this closing section of the essay, we will be providing vignettes narrating key moments in our relationship during the pandemic and whilst writing this essay from our shared point of view. Care, as we have been arguing, is vital, so we will offer ideas around care as tenets of interdependent living, engaging with the importance of solidarity, creativity and love.48

4a. Tea, Okonomiyaki, and More Birthday Cake

Being together in the “mess” of the pandemic has been crucial at a time where we have been exhausted from having to explain our experiences and from having to be patient with others who do not have the awareness or experience to understand our reality, and constantly having to prove our value and worth in order to access daily essentials, healthcare, work and life.49 As we have been demonstrating, the concept of access intimacy encapsulates the importance of having people in your life who have a deep understanding of your experience and prioritize your access to all realms of life.

In the final edit of this essay, we were introduced to the concept of access intimacy by Theodora, one of the editors of this special edition. As we sat next to each other in Denise’s living room, holding large mugs of tea, we first read Mia Mingus’s essay on “Access Intimacy” on different laptops.50 We both read and stopped reading at the same line, which we have included in our glossary and referred back to several times during writing. As is quite common for us, we communicated through a look, and then both paused to say “this is it, this is what it is, this is our relationship.” We paused and reflected on all the mess we have been in together from the start, the pandemic in particular, which we have been processing through writing, editing, talking, laughing, and crying our way through.

With access to lateral flow tests and vaccinations, our lives have changed significantly in the different phases of the pandemic and through the writing of this essay. However, the following vignette offers insight into the intuitive attention we provide each other regarding our access needs, which gives shape to how we practice access intimacy and the sheer joy that comes from this, whilst still navigating hostile environments.51

When Sophie visited Denise in November 2021, it was the first occasion since the pandemic began for us to be together inside. We isolated and tested so this could happen—the first non-family house visit. In the kitchen, Sophie managed all the tasks involving wet hands and Denise gave clear instructions whilst taking charge of the frying. We made okonomiyaki (Osaka style savoury pancake), a cucumber salad and rice for dinner and enjoyed locally-made vegan doughnuts for dessert. It was a really special meal, we celebrated many things. There was a sense of it being a new chapter in the pandemic as we could physically be in the same indoor space. We cooked, ate together, and hugged. Being together in such a way allows us to bear the ongoing challenges of the pandemic and gives us something to look forward to in the future, enjoying our shared love—food.

We both love food; it contributes holistically to our well-being, and the choices we make around which food we eat together adds a sense of celebration and shared joy. As we both encounter reminders of non-belonging often, the practice of sharing food and the importance we place on particular foods works against this and allows us to create a space of belonging with each other.52 This practice of sharing food is not exclusive to our relationship but also to our wider support network, which has always been important to us.

In the middle of summer 2021, we climbed Pen y Fan, the highest peak in South Wales, to celebrate Sophie’s birthday with our closest friends.53 As we walked, we shared homemade cakes and stories. The members of this group are an important part of our network of care. When climbing a mountain, a goal is to climb to the summit. Similarly, this trip marks a special point at which, despite all the challenges of the pandemic, we are all still here, fully vaccinated and living a full life.

Climbing the mountain together has been key to the feeling of success and achievement. If we didn’t eat together, if we didn’t hike together, if we didn’t plan the trip together or share stories together, there would be no meaning to achieving the goal of climbing to the summit: the journey of walking up and down the summits, together, is what mattered the most.

4b. Where People Flourish: our call for growing caring networks!

Through discussing our experiences during the pandemic, we elaborate on how we are being made vulnerable and ungrievable and how the pandemic has consistently challenged our sense of embodied belonging. As a POC and as a disabled person, we have deeply political bodies and could have joined the disproportionate number of our marginalized comrades lost so far.54

Communities of care must be accessible to all and prioritise those who are marginalized.55 We recognize the need for caring communities, which create environments where people flourish and practise interdependency and access intimacy.56 Communities can organize goals addressing the growing pressures of living in an era of neoliberalism and capitalism, including, sharing resources, spaces, skills, and time to work towards mutual thriving.57 For example, the British East and Southeast Asian Network aims to promote positive representation of the East and Southeast Asian population in the UK using podcasts, providing space to share food, workshops, and training for allies.58

The concept of embodied belonging allowed us to engage with deeply felt experiences of navigating society, institutions, and systems of care.59 This process invigorates hope in reconnecting with our deeply political bodies at a time where such connection is most fragile and vital. We argue the importance of forming caring communities accessible for all and supporting existing networks in your local communities based on the concept of mutual aid, sharing resources, cooperative working, and acknowledging interdependence.60

5. Concluding Thoughts

There was so much work throughout the pandemic to keep us both healthy and to safeguard our lives and our wellbeings. The mountain climb truly began from the moment we met, and we are continually hiking up metaphorical mountains together, mountains like new diagnoses, encounters with ableism, racism, xenophobia, marriage, moving house, and celebrating milestones. The opportunities we have to share our lives with each other and our network gives us the fuel to keep going, to keep resisting, creating, and working. The strength we gain from our caring connections ensures that we are also key sources of support for each other and many others around us. The access intimacy present in our relationship gives us the much needed foundation to work and grow from. Without strong close friendships like ours, the limitations placed upon marginalized individuals like us are compounded. By resisting together, we are empowered to be central to our care networks and to connect with and support others, who have also faced othering and exclusion. Together we flourish.

6. Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the vital work of Lausan and other independent publications in HK, specifically addressing the ongoing civil unrest. The courageous work of these activists and journalists is essential in providing a richer picture of what’s happening in HK. We are aware that similar publications are being shut down, and arrests are being made, so we cannot guarantee that Lausan will still be accessible at the time of publication. 香港加油!

Notes

- Vera Chok, “Yellow,” in The Good Immigrant, ed. Nikesh Shukla (London: Unbound, 2017), 39. ↩

- Zuzana Maďarová, Pavol Hardoš, and Alexandra Ostertágová, “What Makes Life Grievable? Discursive Distribution of Vulnerability in the Pandemic,” Czech Journal of International Relations 55, no. 4 (2020): 12, https://doi.org/10.32422/mv-cjir.1737. ↩

- Maďarová, Hardoš, and Ostertágová, “What Makes Life Grievable?,” 12. ↩

- Dominik Mattes and Claudia Lang, “Embodied Belonging: In/exclusion, Health Care, and Well-Being in a World in Motion,” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 45 (November 2021): 3–12,

- Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice,” Leaving Evidence, April 12, 2017, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-and-disability-justice/. ↩

- Mingus, “Access Intimacy.” ↩

- Department of Health and Social Care, “Clinically Extremely Vulnerable Receive Updated Guidance in Line with New National Restrictions,” GOV.UK, November 4, 2020, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/clinically-extremely-vulnerable-receive-updated-guidance-in-line-with-new-national-restrictions. ↩

- NHS, “Important Advice to Keep You Safe from Coronavirus,” letter posted to Sophie, March 21, 2020. ↩

- SARS was a pandemic that extended beyond Asia, even though the severity and impact was not as prevalent in the West. However, it was reported that the Chinatown areas in New York City, for example, were deserted, as Western society equated East Asian people homogeneously with the virus. See Kim Yi Dionne and Fulya Felicity Turkmen, “The Politics Of Pandemic Othering: Putting Covid-19 In Global And Historical Context,” International Organisation 74, no. S1 (December 2020): E213, https://doi:10.1017/S0020818320000405. ↩

- Sophie Savage, “The Heaviest Burdens and Life’s Most Intense Fulfilment: A Retrospective and Re-Understanding of my Experiences with Childhood Liver Disease and Transplantation,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Disabled Children’s Childhood Studies, ed. Katherine Runswick-Cole, Tillie Curran, and Kirsty Liddiard (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2018), 41–56, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54446-9. ↩

- The Care Collective, The Care Manifesto: the Politics of Interdependence (London: Verso Books, 2020), 1. ↩

- Beth Cruse et al., “LIVE: Bristol Protests for Anti-Lockdown, NHS Pay and Palestine Solidarity Taking Place Today,” Bristol Live, May 15, 2021, https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/live-bristol-protests-anti-lockdown-5418526. ↩

- Liz Sayce, “The Forgotten Crisis: Exploring the Disproportionate Impact of the Pandemic on Disabled People,” Health Foundation, February 21, 2021, https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/the-forgotten-crisis-exploring-the-disproportionate-impact-of-the-pandemic. ↩

- Maďarová, Hardoš, and Ostertágová, “What Makes Life Grievable?,” 12; Mattes and Lang, “Embodied Belonging,” 3. ↩

- Mingus, “Access Intimacy.” ↩

- Migrants and minority populations have often been discriminated against and blamed for spreading infectious diseases, particularly during pandemics. See Zuzana Maďarová, Pavol Hardoš, and Alexandra Ostertágová, “What Makes Life Grievable? Discursive Distribution of Vulnerability in the Pandemic,” Czech Journal of International Relations 55, no. 4 (2020): 11, https://doi.org/10.32422/mv-cjir.1737. SARS was a pandemic that extended beyond Asia, even though the severity and impact was not as prevalent in the West. However, it was reported that the Chinatown areas in New York City, for example, were deserted, as Western society equated East-Asian people homogeneously with the virus. See Kim Yi Dionne and Fulya Felicity Turkmen, “The Politics Of Pandemic Othering: Putting Covid-19 In Global And Historical Context,” International Organisation 74, no. S1 (December 2020): E213, https://doi:10.1017/S0020818320000405. ↩

- Bessel Van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score (London: Penguin Books, 2015), 54. ↩

- World Health Organisation, “Updated WHO Recommendations for International Traffic in Relation to COVID-19 Outbreak,” World Health Organisation, last modified February 29, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/updated-who-recommendations-for-international-traffic-in-relation-to-covid-19-outbreak; Steve West, university-wide email to author, March 5, 2020, https://comms.uwe.ac.uk/t/2GDZ-1K2U1-0E232M8C37/cr.aspx. ↩

- Mingus, “Access Intimacy.” ↩

- Margrit Shildrick, “Staying Alive: Affect, Identity and Anxiety in Organ Transplantation,” Body & Society 21, no. 3 (2015): 31; https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X15585886/. ↩

- Shildrick, “Staying Alive,” 32. ↩

- Shildrick, “Staying Alive,” 33. ↩

- Rachel Schraer, “Dominic Cummings: What was on his Whiteboard?” BBC News, May 26, 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-57254654/. ↩

- Sayce, “The Forgotten Crisis.” ↩

- Karl Knights (@Inadarkwood), “Because living with the normalisation of eugenics every day in the UK is unbearably hard, I am once again presenting you my favourite video on the internet,” Twitter, February 24, 2021, https://twitter.com/inadarkwood/status/1364671979710734338/. ↩

- Sayce, “Forgotten Crisis.” ↩

- Knights, “Because living.” ↩

- Sayce, “Forgotten Crisis.” ↩

- Ana Bê Pereira, ”Employment, Ableism and Uber-Performance: Towards a Crip-Queer Theory of Resistance,” Queer Disability Studies Network, accessed October 6, 2021, https://queerdisabilitystudies.wordpress.com/employment-ableism-and-uber-performance-towards-a-crip-queer-theory-of-resistance. ↩

- Pereira, “Employment, Ableism.” ↩

- Pereira, “Employment, Ableism.” ↩

- Vincent Wong and JS, “Beijing’s new national security laws and the future of Hong Kong” Lausan, May 22, 2020, https://lausan.hk/2020/beijings-new-national-security-laws-and-the-future-of-hong-kong. ↩

- Lausan Collective and IZ3W, “Hong Kong’s Colonial System is Still Intact,” Lausan, October 25, 2021, https://lausan.hk/2021/hong-kong-colonial-system-is-still-alive; Zoe Zhao, “Facing Down the Hong Kong Protests’ Right-Wing Turn,” Lausan, March 28, 2020, https://lausan.hk/2020/facing-down-the-hong-kong-protests-right-wing-turn; Vincent Wong, “Where neoliberalism and authoritarianism meet,” Lausan, August 3, 2020, https://lausan.hk/2020/where-neoliberalism-and-authoritarianism-meet. ↩

- Shui-yin Sharon Yam and Hung X.L., “Hong Kong’s Mass Arrests are an Assault on Grassroots Advocacy,”Lausan, January 7, 2021, https://lausan.hk/2021/hong-kong-mass-arrests. ↩

- Edward Hon-Sing Wong, “Insurgent Politics Amid Hong Kong’s Existential Crisis,” Lausan, August 30, 2019, https://lausan.hk/2019/insurgent-politics-against-the-backdrop-of-hong-kongs-existential-crisis. ↩

- Viv Yau, “Meet Viv’s Boyfriend: Inter-racial Dating, Who’s Funnier: Jollof Rice and Noodles,” in But where are you from?, besea.n, July 18, 2021, Podcast, 01:10:00, https://open.spotify.com/episode/2c4naOWvMlwkKsMx0RKWTl?si=Nr8G-M4-RBiXGnjyOQf52Q. ↩

- Lee, “East Side Voices,” introduction to Essays Celebrating East and Southeast Asian Identity in Britain (London: Sceptre, 2022); Vera Chok, “Yellow,” in The Good Immigrant, ed. Nikesh Shukla (London: Unbound, 2017), 43. ↩

- British East and South East Asian Network, “Mission Statement,” besea.n, last modified January 29, 2021, https://www.besean.co.uk/mission-statement; Georgie Ma, “Highs and Lows of Being a British Born Chinese (BBC),” in Chinese Chippy Girl, August 7, 2021, Podcast, 36:00, https://open.spotify.com/episode/6iPcVmCiWYpLV3Ygyvpd5t/; Annie Oh, “Susie Lau aka Susie Bubble,” in Don’t Call Me “Exotic,” March 3, 2022, Podcast, 43:00, https://open.spotify.com/episode/0oyQIkI1BtOBE2ovndUyGL?si=XiKHWpvsRoSBlv2KwthLEg/. ↩

- Alexa Phillips, “‘Coronavirus Given The Face Of An East Asian Person’: Parliament Debates Racism during Pandemic,” Sky News, October 13, 2020, https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-given-the-face-of-an-east-asian-person-parliament-debates-racism-during-pandemic-12102897. ↩

- Nini Fang and Shan-Jan Sarah Liu, “Critical Conversations: Being Yellow Women in the Time of COVID-19,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 23, no. 2 (2021): 334, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2021.1894969/. ↩

- Fang and Liu, “Critical Conversations,” 336. ↩

- Fang and Liu, “Critical Conversations,” 337. ↩

- Fang and Liu, “Critical conversations,” 337. ↩

- Denise Wong and Davina Vencatasamy, “Intersectionality of Gender, Age and Being ‘Yellow’: Experiences of an East-Asian Music Therapist” (virtual poster presentation, European Music Therapy Conference, Edinburgh, Scotland, July 8–12, 2022);

Davina Vencatasamy, “Episode 71 Denise Wong,” in Music Therapy Conversations, British Association for Music Therapy, February 22, 2023, Podcast, 01:10:41, https://www.bamt.org/DB/podcasts-2/denise-wong. ↩

- Fang and Liu, “Critical conversations,” 337. ↩

- Francis Myerscough and Denise Wong, “(Un)Learning from Experience: An Exposition of Minoritized Voices on Music Therapy Training,” Music Therapy Perspectives 40, no. 2 (2022): 138, https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miac024. ↩

- Mingus, “Access Intimacy.” ↩

- The Care Collective, Care Manifesto, 57. ↩

- Mingus, “Access Intimacy.” ↩

- Mingus, “Access Intimacy.” ↩

- Mingus, “Access Intimacy.” ↩

- “Actively creating positive affective ties to place through sensorial practices such as food sharing can equally contribute to people’s sense of belonging and well-being.” Mattes and Lang, “Embodied Belonging,” 7. ↩

- Located inside the Brecon Beacons National Park, Pen y Fan is one the most popular walks in Wales and is South Wales’ highest peak (at 886 metres above sea level). The mountain is just over one and a half hours away from where we live in Bristol, and it was an easy day trip for us. See Daniel Graham, “Walk: Pen y Fan, Powys,” BBC Countryfile Magazine, published September 8, 2022, https://www.countryfile.com/go-outdoors/walks/pen-y-fan-brecon-beacons-wales. ↩

- Maďarová, Hardoš, and Ostertágová, “What Makes Life Grievable?,” 13. ↩

- The Care Collective, Care Manifesto, 37–45. ↩

- The Care Collective, Care Manifesto, 45. ↩

- The Care Collective, Care Manifesto, 46; Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, “Still Dreaming, Wild Disability Justice Dreams At The End Of The World,” in Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories From The Twenty-First Century, ed. Alice Wong (New York: Vintage, 2020), 253–256. ↩

- British East and South East Asian Network, “Mission Statement,” besea.n, last modified January 29, 2021, https://www.besean.co.uk/mission-statement. ↩

- Mattes and Lang, “Embodied Belonging,” 4. ↩

- The Care Collective, Care Manifesto, 37–45. ↩