The city is the site where people of all sorts and classes mingle, however reluctantly and agonistically, to produce a common if perpetually changing and transitory life . . . . And in the long history of urban utopianism, we have a record of all manner of human aspirations to make the city in a different image . . . . The recent revival of emphasis upon the supposed loss of urban commonalities reflects the seemingly profound impacts of the recent wave of privatizations, enclosures, spatial controls, policing, and surveillance upon the qualities of urban life in general, and in particular upon the potentiality to build or inhibit new forms of social relations (a new commons) within an urban process influenced if not dominated by capitalist class interests.

— David Harvey, Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution.1

In recent years, there has been a surge of housing rights related protests around the globe. In these struggles, residents fought against forced demolition of their homes. The fierce and at times violent protests in Korea’s Longshan, Hong Kong’s Tsaiyuan Village (菜園村), and China’s Chong Qing City offer a few examples. These discontents signal a defect in local, regional, and global methods of urban governance, which demand reconsideration and reconstitution. To safeguard individuals’ right to the city, especially the right of marginalized populations, an inclusive approach to urban government becomes vital. Aside from the introduction of Taiwan Alliance for Victims of Urban Renewal, this paper highlights two of the numerous protest artworks in Taipei’s housing rights movement: Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line.

An analysis of their nature and dynamics helps investigate the relationship between protest art and the neoliberal city. Both works combined multiple art forms for activism. Operation Little Barbarossa was a temporary, guerrilla-style urban “infiltration.” Initiated by the art collective 小ACT (Little Act), this protest artwork utilized sculpture, participatory performance, and textual information. Cooking at the Front Line, a student-run kitchen, was a long-term protest action. This initiative employed cooking, graffiti, graphic design, and photography. Although Operation and Cooking applied different approaches to art as protest, both emphasized public participation. Furthermore, both point to the importance of Participatory Art in Taiwan’s grassroots movements.

Neoliberal City

In the global, capitalist economy, cities are managed as businesses through neoliberal policies. According to Peck and Tickell, neoliberalism embodies a type of free-market economic theory. Operating on the “logics of competitiveness,” this model prioritizes market expansion and opposes all collectivist strategies.2 Trouillot further asserts that neoliberalism champions “market extremism,” as it bears the notion that the market is “not only the best, but the only reliable social regulator.”3 In Trouillot’s opinion, this idea can be used as an argument against liberal democracy. At the same time, Peck and Tickell delineate that the neoliberal theory has become “the dominant ideological rationalization for globalization and contemporary state ‘reform.'”4 Regarding neoliberalism’s effects on government and on social welfare, Bourdieu maintains that this framework erodes state organizations. This erosion, according to Bourdieu, occurs through the building up of “agents of finance, budget, militarism, and the rule of law.”5 In Bourdieu’s view, these institutions possess the potential to safeguard the interests of the dominated and those under cultural and economic disadvantage. However, there is potential in reversing this breakdown of protective mechanisms for the underprivileged. Kingfisher and Maskovsky suggest that one should treat neoliberalism “as a process rather than a fait accompli.”6 If neoliberalism is a process, then Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line attempted to subvert Taipei’s neoliberal trend through civic participation.

Taipei’s current political, economic, and cultural debates on urban renewal can be understood within the context of neoliberal policies. Manufactured in Chicago and marketed in Washington DC, New York, and London, neoliberalism was imported to Taiwan after the 1990s.7 Lee Zong-Rong, an assistant research fellow at the Institute of Sociology at Academia Sinica, explains that prior to the 1990s, Taiwan’s economic development was supported by small and medium enterprises (SMEs); however, after the 1990’s, Taiwan experienced political emancipation and economic liberalization.8 Thus began the privatization of formerly public sectors, such as telecommunications, oil, finance institutions, and financial-holding companies. Corporations that controlled these private sectors proceeded to establish close working relationships with powerful politico-economic entities. Consequently, financial enterprises began to influence government decisions through these established connections. In turn, the US-trained, neoliberal government officials encouraged the simultaneous liberalization of Taiwan’s economy and politics. Family-owned companies such as Taiwan High Speed Rail, Far East Tone, and Taiwan Mobile received privileges, thriving and expanding on exclusive opportunities.9 Lee notes that 80% of major corporations in Taiwan are now controlled by Taiwan’s network of elite families, and these corporations continue to expand unchecked due to these “abnormal” political-financial relations.10 Lee explained the politico-economic elite’s incentive to push and implement neoliberalism in Taiwan. His two-year investigation into Taiwan’s politico-entrepreneurial intermarriages indicates the intertwining of the nation’s political and economic interests. The findings reveal that Taiwan’s upper class is in fact “one big family.”11 The grip and strength of this political-entrepreneurial unit are blatant in Taipei’s urban development.

Following the economic recession of 2009, Taiwan’s socioeconomic disparities have become more prominent than ever. According to statistics from the Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, the annual income of Taiwan’s top 20 percent of richest families is 8.22 times higher than that of the island’s lowest-income families. Lee warns that unless the government “introduces relevant taxes on wealth . . . and social welfare measures,” the “one Taiwan, two societies” phenomenon would worsen.12 Regarding government regulation on property value inflation margin, Lee maintains that government regulation is essential because of the fundamental concept that land is public property. In other words, “all citizens have the right to dwell [on it].” He reports that the market is usually regulated by the government in Northern and Central European countries, and unlimited increase in housing prices rarely exists in these nations. In contrast, “there is no limit in real-estate market inflation in Taiwan.”13 Lee states that in Taiwan, financial corporations trade and speculate land to make exorbitant profits. Moreover, the government, believing that economic growth improves life quality, encourages and assists in property speculation. As a result, the unregulated major enterprises are allowed to expand ad infinitum. “The Grand Families of Taiwan” made a valid claim in stating that “there’s nothing wrong with members of these extended families supporting each other” and strategizing to advance family interests. However, the authors accurately concluded that it is necessary to consider “how these family conglomerates can be prevented from standing on the opposite side of the greater public good as they thrive and prosper in pursuit of lasting business success.”14

The two protest artworks featured in this article can be interpreted as a reaction to the unchecked corporate-governmental collaboration in land speculation and the consequent infringement of citizens’ rights to housing and public space. Through Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line, the artists and the participants exerted their right to the city. Via participatory art, among other art forms, they rendered themselves visible in the urban landscape and championed the housing rights of the professional and working class. If their actions did not defeat the waves of “privatizations, enclosures, and spatial controls” evident in the neoliberal city, as described by Harvey, they did demonstrate a new form of social relation, a “new commons” through protest art. As illustrated in later sections, their approach to the fight against “capitalist class interests” in urban renewal was at once creative, convivial, and combative.15

The birth of Taiwan’s housing rights movement occurred around the same time as the country’s neoliberalization. In 1989, close to five hundred thousand people marched to the streets due to the unreasonable spike of housing prices. On August 26, 1989, the protesters, organized by the Homeless People Alliance, spent the night on the avenue of Section 4, Zhongxiao E. Road in Taipei. One month later, the protesters camped for three days at the Cathay Insurance Headquarters on Renai Road. A wedding ceremony for a hundred homeless couples were held at Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall. The fight for affordable housing would continue in Taiwan until the present day.16

Beginning in 2007, Taipei’s neoliberal urban (re)development reached a new height. Real estate developers and the Taipei City government collaborated to create a “New Taipei.” Without the general population’s knowledge, various “urban development programs” went underway. These renewal schemes came in the name of “International Cultural Event,” “Tourism Development,” and the more recent “Four Golden Blocks Plan” and “Taipei Wall Street.” The rhetoric of these building plans, according to the Taipei City government, was to put Taiwan’s capital city on the global map. However, critics maintained that this attempt to transform Taipei’s urban landscape was, in reality, an effort to procure more land and capital by the political-economic elite. This view would be supported by a survey of urban development programs in Taipei from 2004 to 2014. During this period of “urban progress,” numerous communities across Taipei City and its peripheral districts became affected. Most of the residents in these communities came from the professional-working class. For instance, in 2009, a portion of the Lo-Sheng Sanatorium, a home for patients with Hansen’s Disease (or leprosy), was demolished despite vigorous protests and continuous negotiations by residents and their supporters.17 In central Taipei, low-income dwellers in two communities, Huaguang and Shaoxin, received court notices. In these letters, the Taiwan Ministry of Justice sued occupants living in units labeled “illegal” by officials. However, the sued parties had acquired their homes through either inheritance or legal purchase. The court notices mandated that each family self-demolish their homes. Many were ordered to pay compensation ranging from 40,000,000 to 70,000,000 NT (1,250,000 to 2,187,500 USD). The monetary compensation ordered by the court was an astronomical amount to the residents. The deadline to demolish their own homes added crushing pressure on the occupants. In other residential communities, real estate corporations persuaded property holders or their families to sign up for urban renewal programs. Often times, residents signed a contract without any knowledge of the renewal procedure. Many of them realized later that they had forfeited the right to make decisions regarding their own properties.

As a result, the marginalized residents protested. Already underprivileged, they decried the Taipei City government’s harsh and unreasonable actions. The protesters contested their homes’ forcible demolition. They pointed to the high risk of their becoming homeless. As protest and petition, residents hung banners outside their homes and rallied in the streets (figure 1). Their plight reached other citizens in Taipei and around the island of Taiwan. Soon, many concerned citizens joined in resisting the politico-economic elite’s infringement on land, property, and housing rights. They challenged the city government and supported the communities through drawings, music performances, performance art, art installations, graffiti, film, photography, art and history workshops, walking tours, and a flea market. As a result, artists, students, residents, and professionals coalesced in a national housing rights movement (figure 2).

Participatory Art Responds to Neoliberal City

Participatory art is an approach to making art that emphasizes the audience’s direct involvement.18 The audience’s active participation in the creative process is achieved through their corporeal presence. Thus, the participants’ intellectual and creative involvement also becomes critical. In many participatory artworks, members of the public contribute materials that inform the work. Within this art genre, the artist is considered as a collaborator and producer of situations, and the commodified art object is replaced by an ongoing or long-term project.19 Characterized by its public nature, social engagement, collaboration, and collective discussion, participatory art provides an inclusive environment that encourages the examination of serious social matters from creative angles. Its emphasis on social relevance and dialogue makes participatory art a compelling means of communication in the context of urban development. Among markers of neoliberal urban development, which include high-value properties, luxury housing, and cultural institutions, this art genre gives representation to marginalized citizens. Through alliance and partnership, participatory art allows artists and underprivileged residents to rally for an equal right to housing, to urban resources, and to public space in an active and creative manner.

The rise of art works that require active audience participation in the past two decades has prompted various discussions among art historians and critics. Currently, there are several theoretical approaches to participatory art. While Grant Kester and Nicolas Bourriaud champion social interaction rather than the art object itself, Claire Bishop and Hal Foster assert the importance of the artist’s intention, the artistic elements, and the work’s ability to criticize current social conditions. Additionally, Suzi Gablik’s listener-centered paradigm, Suzanne Lacy’s understanding of participatory art as metaphor, and Leonie Sandercock’s attention to “difference” and new ways of knowing are important perspectives for understanding participatory art.20

In Conversation Pieces, Kester showcases several examples of dialogical art that make conversations among participants the focus of the work. Kester argues that art critics and historians can interpret these interactions and conversations themselves as the work’s aesthetic element. Similarly, Nicolas Bourriaud places great emphasis on dialogue in art production, maintaining that the purpose of art is to connect people, to “produce empathy and sharing” and to “generate bonds.” Bourriaud’ s “relationist” theory of art maintains that the interaction, or “inter-subjectivity”, becomes the “quintessence of artistic practice.”21 Although Kester’s and Bourriaud’s observation on the conversational, intersubjective elements of participatory art is significant, other criteria, such as context (conceptual, social, and geographical), varying channels and degrees of public participation, artistic form, content, and craftsmanship, should be included to form the basis for critique.

Taking a different standpoint from Kester and Bourriaud, Claire Bishop argues that art works that seek to create friendly collaborations with public audiences risk the danger of losing the critical function so essential to avant-garde art. Bishop refers to Miwon Kwon’s work in order to contextualize her position. Kwon observes the departure of public art from “heavy metal art” (object-oriented) to a genre that considers the audience (people-centric). She notes that artists are shifting from the traditional view of public art as located in a public place towards the notion that public art includes the public. However, Bishop complains that artists take the intersubjective space created through participatory projects as the focus and as the medium of their artistic investigation, and they do so by concentrating on the relational rather than the aesthetic. For Bishop, it is essential to consider, examine, and compare such works as art. She prefers examples such as Thomas Hirschhorn’s Bataille Monument (2002), Artur Zmijewski’s The Singing Lesson II (2003), and Jeremy Deller’s Battle of Orgreave (2001), which though less aesthetically pleasing and harder to engage, challenge their audiences to think critically about issues such as identity politics, physical disabilities, and conflicts of interest. To Bishop, these artists, along with others discussed in her publication, Artificial Hell, are “less interested in a relational aesthetic than in the creative rewards of participation as a politicized working process”22

Bishop and the art historian Hal Foster both emphasize the importance of social reflexivity and artistic vigorousness for participatory art. Foster worries that the open-ended tendency in relational aesthetics may make art become formless and lose its ability to intervene in the social sphere. He asserts that art should still be able to take a stand, and to do so “in a concrete register that brings together the aesthetic, the cognitive, and the critical.”23 Similarly, Bishop recognizes participatory art’s potential to “lend support to” a larger project of equality; however, she maintains the necessity to “sustain a tension between artistic and social critiques.” Art, in Bishop’s view, should not bear the sole responsibility for devising and implementing a political project, because it is “a form of experimental activity overlapping with the world.” According to Bishop and Foster, it is insufficient to simply consider a gathering of people and their collaboration as a good in itself; collaboration must make artistic contribution as well as social inquiry.

In the essay, “Living Takes Many Forms,” Shannon Jackson reiterates Bishop’s and Foster’s emphasis that participatory art is not the “emptied, convivial party of the relational” or the “romantically unmediated notion of ‘life’ with a generalized spontaneity,” yet she affirms participatory art’s ability to function both socially and aesthetically. She affirms that participatory art can simultaneously be rigorous, formal, and conceptual when it “addresses, mimics, subverts, and redefines public processes.”24 Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at The Front Line match this description, as they not only engaged the public to think critically about the right to the city, but also reversed participatory art’s service to neoliberal urban development. Rather than aiding the neutralization of profit-oriented real estate development, these works exposed problematic urban policies through visual and performance art. And replacing top-down cultural policy tools aimed to eliminate disruptive individuals, Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at The Front Line became bottom-up interventions into existing structural dynamics.25

Lacy, considering the evaluative criteria for participatory art, contends that apart from the artist, audience, and intention of the work, the work functions above all as art, which she defines as a representational model operating as a symbol. She maintains that “perceived notions of change based on political and sociological models and those [notions] extrapolated from personal experiential reports are necessary, but insufficient” in evaluating participatory art. She argues that participatory art must be recognized as a metaphor that attempts to function simultaneously within both social and aesthetic traditions.26 In this respect, Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line could be interpreted as symbols of new forms of urban resistance, which mustered trans-social strata populations, who then dedicated themselves to interdisciplinary, long term collaboration. Artistically, both borrowed military terminologies, such as “army, infiltrate, front line,” and combined mundane objects, cultural references, and everyday acts as protest performance.

Moreover, Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line are to be contextualized within a global network of similar practices. These two works expand the scope of the currently Eurocentric discourse on participatory art.27 Together with examples such as Medical Care for the Homeless in Austria and Project Row Houses in the United States, Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line bring a critical lens to issues of housing, urban development, and the right to the city.28 They point out that regionally and globally, artists and activists are employing participatory art to counteract inequitable urban renewal. The Taipei works will serve as a window to the larger field of global activities and ramifications of contemporary participatory art.

Within Taiwan’s housing rights movement, participatory protest art played a central role in challenging profit-centered urban (re)development. As will be discussed below, Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line used diverse creative methods to garner attention and to create alternative forums for monitoring urban development. Contrary to the conflicts, divisiveness, exclusion, and a detachment from public interest that characterize Taipei’s urban renewal, the responding participatory artworks are premised on communication, collaboration, inclusion, and equality. Through interdisciplinary, trans-social strata collaborations, this coalition called upon governments and city planners to center urban development on citizens’ common welfare and living quality.

Politically, Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line are significant for Taiwan, considering the country’s colonial history. These two participatory street performance art pieces visualize the level of freedom and confidence that the citizens of Taiwan fought for and gained during the transition from the martial law period to the recent years. The oppression of freedom of speech gave way to assertive social and political expressions. The right to assemble and protest may be taken for granted in many countries, particularly in North America and Europe. However, in Taiwan this right is not a given for its citizens, for the Assembly and Parade Act, instituted in 1988 after the lifting of the martial law, still bore the “Martial Law-period mindset, mandating the application for government approval prior to any outdoor assembly or demonstration.”29 Through Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line, the artists and participants spoke out and acted with conviction, vigor, and creative thinking. And they did so without any application or concern for government approval. Instead, through interdisciplinary, trans-social strata collaborations, this coalition called upon governments and city planners to center urban development on citizens’ common welfare and living quality.

小 ACT and Operation Little Barbarossa

In 2010, controversies surrounding the Taipei International Flora Exposition prompted the art collective 小 ACT to respond with a series of participatory performance art actions. Operation Little Barbarossa was the most complex of them all. 小 ACT consisted a team of graduate art students and volunteers from three universities in northern and southern Taiwan. The fact that its members came from different regions of the country illustrated that discontent extended beyond the capital city. The 2010 Taipei International Flora Exposition, which ran from November 6, 2010 until April 25, 2011, was meant to showcase the diverse and unique flora of Taiwan and to promote international trade. However, academics and social activists criticized that this Exposition was a front for real estate speculation.30 小ACT elaborated on this critique in act 01, stating that city officials and developers used the Flora Exposition as an excuse to demolish unsightly homes, integrate land, and build new residential and commercial complexes. The “Taipei Beautiful” policy and the consequent “fake parks” were two major components in Taipei’s building policy that came under scrutiny. To support the critique, 小ACT printed an article titled “There are Plants in the Parks; There are No Houses for Citizens.”31

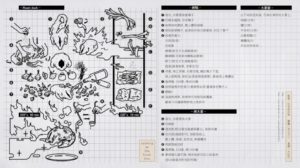

This article explained how the Taipei Beautiful policy produced temporary “fake parks” that benefit not the environment but developers (figure 3). The report indicated that more than seventy empty lots became “fake parks” under the Taipei Beautiful Series Two policy. The reason these parks were called “fake” was that in eighteen months the “useless” small lawns, devoid of any greening effect, would be converted into floor area bonus, allowing land owners and developers to build structures that are one and a half times the original legal height limit. Thus, the temporary, green patches were in effect preparatory lands for luxury residences (figure 4).

小ACT presented its own suspicion toward the Taipei Beautiful policy in a section titled “Taipei Beautiful Point-to-Point Investigation.” The collective maintained that the Taipei City government disregarded the basic principles of green landscape planning, such as bio-diversity and foundation water retention index. Rather than upholding the notion of sustainability in its efforts to create extensive green landscapes, the administration used “green aesthetics” as a catchphrase to produce numerous untended green lawns that destroy Taipei’s urban texture.32

Moreover, the zoning bonus ordinance, a regulation that grants additional floor area building allowance, enabled the demolition of existing historic structures, another disconcerting result of the Taipei Beautiful policy. For example, due to the lack of official “historic building” status, several elegant Japanese-style buildings were destroyed without restrictions.33 These buildings represent Japanese colonialism, an integral part of Taiwan’s history. Their physical disappearance eradicates important visual symbols that remind Taiwan’s people of their national history.

Though economic incentives are the apparent cause for the rapid and rampant destruction of Taipei’s unique architecture, Taiwan’s colonial history might be the primary reason for a widespread disregard for these valuable cultural assets. Ironically, although most of Taiwan’s people initially celebrated Japan’s departure and welcomed the Chinese Nationalists (KMT), they soon realized that the KMT was a militant party that intended to use Taiwan as a temporary base to retake China. The KMT’s political ambitions, its sense of cultural superiority, and a lack of genuine interest in Taiwan’s welfare precipitated the island-wide pillage and rape as well as the subsequent February 28 incident and White Terror.

Like Japan, the KMT government coveted Taiwan’s rich natural resources and labor and treated the non-Mandarin speaking population—the Taiwanese-speaking, Haka-speaking, and aboriginal groups—as inferior. Discrimination and segregation were common in professional and everyday settings. Taiwan’s people, who imagined a return to the “warm embrace of motherland,” were greatly disappointed because they not only remained “second-class citizens” but were traumatized into another silent oppression under a new military dictatorship. Historical factors may explain the government’s aggressive development schemes and its thoughtless demolition of older buildings island-wide. The KMT’s antagonism toward the Japanese colonizers and their derision of non-Mandarin speaking groups contributed to Taiwan’s current cultural identity confusion, fragmentation, and political indifference. Despite the Cultural Heritage Preservation Act, numerous fine Fujian and Japanese style residences continued to be demolished in the urbanization process of the 1900s.34

The International Taipei Flora Exposition did not enrich citizens’ cultural awareness. On the contrary, it was superficial, extravagant, financially unsustainable, and environmentally destructive. The article, “Fragrant Flowers or Lethal Weapon Iron Tribulus? The Sustainable Actions and Strategies Activated by the Unjustified,” supports this idea. In this critique by the architecture professor and member of OURs (Organization of Urban R-s), Huang Jui-mao argued against the Flora Exposition from various perspectives.35 First, Huang maintained that Taipei’s citizens had little use for the obscure, transient “fake parks,” which lack any recreational facilities or community interaction. Second, Huang reiterated that the Flora Exposition benefited only government officials and developers but was financially nonviable for Taiwan. From a marketing perspective, he pointed out that the “International” Flora Exposition, contrary to its title, targeted domestic consumers rather than international visitors.36 Thirdly, Huang suggested that in the pre-exposition preparation, the city government’s true motivation was to clean up the city’s “underdeveloped” areas and to “create stratified landscapes in order to enlarge the real estate market.” Huang criticized the Taipei City government’s developmentalism-driven urban policies and argued that the city administration could have used this large-scale event as an opportunity to advance urban infrastructural adjustment by reaching a common ground on Taipei’s urban development. Unfortunately, communication and dialogue with the general public were “non-existent”; instead, contestation for urban spaces began in full-force. Furthermore, the city’s motivation to create a “bourgeoisified urban landscape” became apparent when the officials employed the police to disperse homeless persons.37

Thus, Taipei City’s urban policy recalls the uneven urban development as discussed by Deutsche, Zukins, and Miles, who mainly refer to American examples.38 Taipei’s case demonstrates that the exclusion of the professional-working class and the further alienation of underprivileged citizens were similarly occurring in Asia. In Taipei, it is clear that the city government and associated real estate developers utilized the 2010 Taipei “International” Flora Exposition as a gateway to boost the local housing market. The simultaneous “urban development” was ineffective, detrimental, and exclusive because it overlooked public participation in urban policy-making and solely benefited the politico-economic elite.39 It is evident that the Flora Exposition was used as a cover for “urban cleanup”.40

Expressing the same concerns, 小 ACT denounced the city government’s interest-driven cultural policy by driving into the Exposition. To name their first anti-Flora Exposition action, 小 ACT took inspiration from world history. The title, Operation Little Barbarossa (小巴巴羅薩行動) came from Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s plan to invade Russia during World War II. Operation Barbarossa itself was named after Frederick Barbarossa, a medieval Holy Roman Emperor. Barbarossa means “red beard” in Italian. This name originated from the northern Italian cities Frederick Barbarossa attempted to rule.41 The name was a mark of both fear and respect. 小 ACT appropriated this German imperial title in a mocking manner to highlight its own anti-capitalist actions. Kao Jun-Honn (figure 2), the art collective’s leader, described this piece as an “urban spatial guerilla operation”.42 Operation Little Barbarossa aimed to distribute act publications. These booklets meant to inform the public about the problem of cultural manipulation for neoliberal urban development.

For Operation Little Barbarossa, 小ACT artists went to great lengths to fashion a 100 percent man-powered car, a BMW318. This delivery car was strictly modeled with a 1:1 ratio after an original BMW318 (figure 5). 小ACT chose this particular car to play a joke on the real estate development corporations, which favored the BMW318 for company transportation. Kao also noted that the choice of the BMW318 was satirical because it is also the car model preferred by gangster members in Taiwan.43 The selecting of the BMW318 contained contextual references specific to Taiwan. In this case, it mocked the country’s real estate and mafia cultures. The BMW318’s association with prestige appealed to both the crime syndicate and the commercial real estate sector. Considering this history, 小ACT seemed to imply that the existing profit-driven neoliberal urban development, championed by real estate corporations and supported by the Taipei city government, was criminal activity.

小 ACT’s dedication to its cause was evident in the time and effort they devoted to handcrafting the BMW318 vehicle. To build the car, the artists measured their BMW318 model with a precision ruler and created a blueprint on the computer. For the model car’s central structure, the artists repurposed a four-person tandem bicycle. 小 ACT members made a frame for the car by soldering two-inch angle iron to the tandem bicycle (figure 6). High-density styrofoam was then added to the frame to make the body (figure 7). The artists carved, sculpted, and sanded the styrofoam into shape, a challenging and time-consuming process. They then painted the shell black, and applied varnish to make it waterproof. Members also designed paper tires and wheels, signal lights, license plates, and the BMW logo to make the machine more realistic (figure 8). In the end, the team had no time to install the glass windows and turn signals before their planned journey.44 On a morning in November 2010, 小 ACT set out in their new BMW318 to infiltrate the Taipei International Flora Exposition. Two art students, Lai Jun-Hong (賴俊浤) and Lin Jao-Yu (林昭宇), powered the car. They pedaled from Kuandu, a northern rural district of Taipei, to Yuanshan Station, which was located in Taipei City proper. En route, they traveled along the agricultural roads of Kuandu Plain. Lai and Lin “refueled” at the Formosa Gas Station on Chengde Road, where they distributed the act booklets. At the Giant Bicycle Shop on Zhongshan North Road, they changed a flat tire. As they approached the Flora Exposition, all the intersections were guarded by police officers. At this point, the 小 ACT riders merged into the fast lane by accident at the intersection of Zhongshan North Road and Minzhu Road. The police soon came to investigate. The “drivers” explained that they were there to celebrate the Flora Exposition. The police, believing in their story, allowed them to resume their course. After much labor, 小 ACT succeeded in penetrating the Flora Exposition to disseminate their publication, act 1.

Edited by Kao, the booklet, act 1, and later act 2 and 3, examined neoliberal urban development and real estate speculation. The illustrations and writings explained why the Flora Exposition was deleterious to Taiwan’s finance, culture, and environment. Through act 1–3, 小 ACT called the public into small collective, participatory actions. Though small, these disruptive interventions possessed potential for significant ramifications. According to Kao, Operation Little Barbarossa was very successful.45 On the road, the artists did not have to make much effort to attract people because out of curiosity, they ran or rode toward the BMW318 (figure 9). The “drivers” would distribute the act booklets from within the car. Kao estimated that the team gave out two thousand copies of their publication. During this performance, the news television also continued to broadcast about Operation Little Barbarossa. As journalists interviewed 小 ACT that day, they were able to spread their message to a broader audience. The Operation Little Barbarossa video documentary shows the drivers distributing pink act 01 magazine to pedestrians, gas station workers, and people at bus stops. The documentary photographs that Kao provided depict people focused on reading the act pamphlets at the YuanShan MRT Station Plaza, which was opposite the Flora Exposition venue (figures 10 and 11). Through laborious sculpture-making and arduous, interactive performance art, as well as research and writing, Operation Little Barbarossa reached out to the citizens of Taiwan in a creative and educational manner.46

For the evaluation of Operation Little Barbarossa, Kao’s criteria for success were the completion of “infiltration” by bringing the vehicle into the event venue, the audience’s and participants’ level of enthusiasm, the dissemination of ideas, and national media attention. In terms of Bishop’s and Foster’s emphasis on social reflexivity and artistic vigorousness, Operation Little Barbarossa also met the requirements. The whimsical, handcrafted nature of the BMW car coupled with the labor intensive art-making and performance to make pertinent, well-researched information known to Taipei citizens. However, the nature of this performance made further discussions between the artists and the general public about the act magazine content implausible because of the brief contact between the two parties. The scene in figure 10, where a professor led his students in reading, with a camera recorder on a tripod in the background, appears to be more of a staged scene. Yet Bishop, referring to André Breton’s analysis of the 1921 Dada Season and deducing a “model of delayed reaction,” reminds art historians and critics to delay conclusive judgement of participatory artworks, as their significance, when not understood at the time of their occurrence or in their immediate results, may resonate in the future.47

Two parallel characteristics permeate the art of 小 ACT. On the one hand, the artists created an oppositional, battle-like quality in their works. They employed military terms like “army” and “infiltrate” to describe their activities. One the other hand, humor, irony, and even a sense of mischievousness abounded in Operation Little Barbarossa. This work was the kind of participatory art that challenged people to reconsider the social, economic, governmental, and aesthetic aspects of their everyday life. The same tone and purpose would be echoed in Cooking at the Front Line.

TAVUR

Operation Little Barbarossa provides a glimpse of the citizens’ critique of the neoliberal city in Taipei. While 小 ACT labored to bring awareness to the various issues surrounding Taipei’s profit-centered urban development, such as real-estate speculation, Taiwan Alliance for Victims of Urban Renewal (TAVUR) focused on housing rights. This organization’s efforts are exemplified by its involvement in Wenlinyuan, the most controversial demolition case in Taipei in 2010. Cooking at the Front Line, a student activist-run kitchen at Wenlinyuan, represents the cross-disciplinary collaboration in TAVUR.

It is important to mention the three central figures of TAVUR: Peng Long Shan, Huang Huiyu, and Chen Hongyin (figures 12–14). They became critically aware of Taiwan’s urban socio-spatial inequality through different avenues during the same period of time. With different roles as a resident, an art student, and a student of urban planning, respectively, Peng, Huang, and Chen converged in a forceful, unified, and momentous movement to contest urban inequality. Using a listener-centered paradigm to give voice to marginalized residents, TAVUR became a national, trans-social strata support network. The phrase “Land is not a commodity” encapsulates TAVUR’s ideals.48 Peng Long Shan, a motorbike mechanic and shop owner, became a victim of inequitable urban renewal laws when he was pressured and sued by Sen Yeh Construction Company, after refusing to join the urban revival program in his community, Yungchun. His determination to protect his family’s ancestral property, the learning of other citizen’s stories of oppression, and a strong sense of unequal treatment motivated Peng to organize The Taiwan Alliance for Victims of Urban Renewal (TAVUR) in 2010.

Huang Huiyu was a graduate student in the Department of Trans-Disciplinary Arts, Taipei National University of the Arts. During and art residency, she began to question the relationship between the arts, urban renewal, and community residents. Huang and a group of artists received space to work and exhibit in emptied buildings awaiting reconstruction in Chungjong, Chungzheng District. This area was renamed the Urban Core Arts District by the JUT Development Group. During this time, Huang observed little connection between the art creations in Urban Core and its surroundings. As she investigated, she became frustrated by the fact that information on the fate and future of this community remained unobtainable. As a result, Huang decided to create a site-specific piece about urban renewal. Besides research on urban renewal in Taiwan, Huang employed two methods common in participatory art: interview and conversation. First, she interviewed residents in Chungjong. Huang then organized two symposia that involved both the art community and residents. The symposia asked the question, “What does urban renewal mean?” Following the interviews and symposia, Huang curated a traditional group art exhibition that featured photographs of residents and her fieldwork findings. Huang raised public awareness of and complicated the dominant urban redevelopment system through these efforts.

Huang’s quest led her to a conference and a reading group on urban renewal at National Taiwan University, where she met Chen Hungyin, a graduate of Urban Studies. Having studied urban planning, Chen Hungyin became highly aware of urban renewal controversies in Hong Kong and South Korea while she was working in Korea. Upon her return to Taiwan in September 2010, Chen was shocked by the prevalence of urban renewal programs in Taiwan. After Huang and Chen met, they and several other concerned art and urban studies students visited Peng Long Shan in Yungchun in order to learn more about urban renewal at the community level. Eventually, Huang, Chen, and seven other students joined TAVUR in 2010.49

The Wenlinyuan Controversy

Beginning on December 25, 2011, passengers of the Taipei Metro could see a bright, multicolored banner affixed onto a building as they passed the Shilin Metro Station in northern Taipei (figure 15). The building was called Wenlinyuan. It belonged to the Wangs, a family that contested the forced demolition of their ancestral home. The colorful banner featured 100 small figures holding hands and a large, red and black slogan, “Home, Not for Sale and Not for Demolition.” This collage on fabric was the result of a participatory art event titled “One Hundred People Paint to Protect the Wangs.” Organized by TAVUR on the evening of December 24, 2011, this event invited the general public to Wenlinyuan to participate. The resultant protest banner with painted figures was attached to a sizable piece of fabric (figure 16). On the banner, each figure was connected by a hand to show solidarity and protection. Different signs and phrases were also inscribed on the figures, such as a dollar sign, the words, “home,” “stay,” and the phrases, “not for sale,” and “you also became the victim.” The banner was both a statement and an invitation to its viewers. It conveyed the Wangs’ and their supporters’ determination to protect Wenlinyuan from demolition. The banner also urged its viewers to learn more about the controversy by visiting TAVUR’s Facebook page. “One Hundred People Paint to Protect the Wangs” held significance because it pointed to the level of attention to and support for housing rights in Taipei, and by extension, in Taiwan. Moreover, it demonstrated increased civic engagement by youths and young professionals of Taiwan. Furthermore, participatory art became the tool to garner momentum and spread the message.

Despite the “One Hundred People Paint” banner and several protests and press conferences, Wenlinyuan was eventually forcibly demolished in the early morning of March 28, 2012. On the evening of March 27, more than 300 students and supporters gathered in front of Wenlinyuan to protect it from the anticipated forced demolition.50 Many of them lay on sleeping bags laid out on the ground, ready to resist eviction (figure 17). Others held discussions under a tent decorated with colorful figures. The front of the tent also displayed the phrases “Urban Renewal; Forced Demolition; Unconstitutional.” According to Peng, around one thousand police were sent to evict the Wangs and all those present (figure 18). After the eviction, the Wangs and their supporters returned to construct a temporary hut next to the rubbles (figure 19). However, violent eviction was not the end of the TAVUR members’ troubles. They continued to receive pressure and threats from developers. The developer Leyoung Construction Limited employed gangsters to taunt, tease, and harass the Wangs and the Alliance staff. A bulldozer parked in the demolished area continued its attempt to destroy the hut and remove the remaining rubbles (figure 20). Violent clashes occurred when TAVUR members tried to stop construction workers from building illegally. In response, student supporters took watches to guard the Wangs’ property. They also video-recorded the construction workers’ movements as evidence (figure 21).

Cooking at the Front Line

Eight months after the eviction incident and the intensive guarding of the Wangs’ land, the TAVUR student members aimed to set a different tone for Wenlinyuan. They recognized the existing sentiments of struggle and conflict, and hoped to project a warmer, more convivial and inviting atmosphere. The result was the addition of a kitchen adjacent to the temporary hut. The student staff of TAVUR decided to build a kiln. Their intention was to allow all supporters to collaborate and become acquainted with one another through this complicated process. Soon, the kitchen project, Cooking at the Front Line, began to produce savory dishes and breads in assorted shapes and flavors. These creations were shared among visitors and delivered to other communities that were struggling with eviction. Contrary to the destructive demolition and the constant conflicts that had characterized Wenlinyuan, Cooking at the Front Line produced products that could cheer and sustain residents and community members. The making and sharing of food from the Cooking at the Front Line kitchen added a softer side to the hard struggles against eviction.51

Though based in Taipei, Cooking at the Front Line‘s activism spread beyond the capital city. For example, its members traveled to various locations around Taiwan to cook for housing rights and other socially-conscious groups (figure 24). On their journeys, Front Line members exchanged stories and information with whom they encountered. To reach out to the online population, the group’s blog featured fully-illustrated recipes used in the Front Line kitchen (figure 25). Moreover, contributions from all parts of Taiwan enriched the project’s participatory aspect. Supporters and small business farmers would donate produce to express solidarity. In addition to a turkey, a duck, strawberries, and rice, these gifts included mangos produced in Chiayi (嘉義) and mailed from Tainan (台南). Sometimes, the fresh products were a thank you present from recipients of Cooking at the Front Line‘s gourmet breads. Other times, the donating parties received goods from the Front Line kitchen, which incorporated the ingredients they donated. For instance, Front Line members turned the mangos from Chiayi into jam and dried pieces before blending them into homemade nuggets. They then sent some to the mango grower in Chiayi.52 This traveling back and forth of raw ingredients and their final transformation illustrated a sense of reciprocity. This type of alternative economy stood in sharp contrast to the neoliberal framework that dominated Taipei’s urban renewal. Furthermore, the building of relationships through food and networking demonstrated the relational and practical nature of Cooking at the Front Line. The breath and depth of research required to understand different rights-related case studies showed the Front Line members’ inquisitiveness. Their ability to synthesize and imbed ideas in story-like, readable blog posts revealed their tact. Their power, creativity, and craftsmanship were attested by the successful recipe experiments and the output of quality food.53

Regarding design, artistic intention became evident in all aspects of Cooking at the Front Line. For example, bulldozer-shaped latches were crafted and fitted onto the kiln’s door. An intricate “OVEN” trademark was placed in the center of the brick arch that framed the kiln opening (figure 22). Also, each type of bread was carved with “signature patterns” that expressed the members’ creativity (figure 23). Besides the handcrafted artisan breads, the most singular aspect of Cooking at the Front Line was the outfit worn by its members (figure 24). While the clothing was typical of those worn by Taiwanese youth, a few accessories stood out. They include hats, helmet, masks, gloves, and scarves. Cute, comical adornments were often combined with edgier embellishments. For example, a female student always wore a cartoon-like mask and mitten or gloves. Her mask resembled a teddy bear’s face that was at once funny and angry-looking (figure 23). The mitten and gloves might have been worn for practicality, though they also added a sense of strength and theatricality. Another female student sported a light blue headpiece in the appearance of a soft toy dog. This gentle-looking mascot was paired with scarves that covered part of this student’s face. In the same image, a female student modeled a bright yellow mask that appeared be Pikachu’s face.54 The Pikachu, cartoon bear, and cartoon dog symbols represent the adoration of cuteness in Japanese popular culture. As demonstrated by Cooking at the Front Line, Japanese popular culture influenced Taiwan’s youth even at the university level. Meanwhile, the male student members often wore masks and scarves that concealed their faces and necks. This attire made them appear rebellious and somewhat threatening (figures 23, 24, 26–28, 29). According to the Cooking at the Front Line blog, Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos inspired this fashion choice. Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos was the nom de guerre of the Mexican Zapatista Army of National Liberation’s main ideologist, spokesperson, and de facto leader. By combining references to popular culture and history of revolution in their outfits, the Cooking at the Front Line students achieved a unique visual blend of charm and subversion.55

When photographed, the students also incorporated various kitchen tools and food items as props. This helped conceal their identity. The props, along with the outfits, created images that were at once a comical, absurd, and aggressive. A special bread peel featured an illustration of a human face (figure 26-27). Cutouts were made onto the metal plate to create a menacing expression. The face featured furrowed brows, narrow eyes, flaring nostrils, and a wide-open mouth with only a few teeth remaining. In addition to retrieving bread from the brick kiln, the bread peel can function as an offensive or defensive weapon. The students combined everyday objects with their on guard gestures to convey a determination and tenacity to fight (figure 26-27). In one photograph, five students occupy the narrow kitchen space in various positions (figure 26). Each holds a common kitchen tool as they stare directly into the camera lens. Two male students in hats and masks sit on the kitchen walls with a bread peel and blender in hand. They flank the seated female student in the bear mask, who covers a piece of rounded bread with her gloved hands. The manner in which she holds the bread could suggest protection. Another female student stands behind, as she grips a cleaver and a chopping board that could be used as an attacking knife and a shield. Further back, another student leans across the top of the kiln, seeming to claim ownership. While the height of her position is impressive, her raised leg, faux mustache, and what appears to be a pink snake, produce a farcical effect. Overall, this group photograph communicates that the chef team is serious about occupying and defending Wenlinyuan and its makeshift kitchen. The same spirit is evident in other photographs (figures 26 and 27). Two students in the front positioned tomatoes and cleaning brushes over their eyes as disguise (figure 27). The student at the back covers his face with the specially designed bread peel. Protruding horizontally from the kitchen wall, he resembles a ninja. In another, the Front Line members pose in front of the graffiti wall of the temporary hut (figure 28). This dramatic setting and the students’ poses make them appear as if they are ready for battle. Visible in the foreground are bulldozer treads and rubble. Three students stand atop or behind the sandbag wall, which is surrounded by yellow tape that signals “no crossing.” The student to the left, wearing a mask, holds out a bunch of green onions as if to challenge any intruders. The middle figure stands in defiance with hands at his waist. The one on the right squats as he displays a large pot and a colander. Their stances declare to the viewer that Cooking at the Front Line is not threatened but is prepared to keep defending citizens’ housing rights.

The visual presentations and the performative elements of Cooking at the Front Line are to be viewed as symbols and tools for urban resistance. Huang noted that their outfits, particularly the masks, served to “emphasize the sense of unity in that space of protest.” “What mattered even more were the team’s intentions and activities. Cooking and managing the kitchen provided internal healing and empowerment.”56

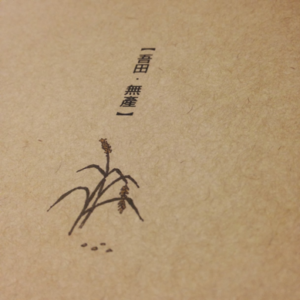

In addition to baking and cooking, students also utilized their artistic talents to design notebooks for fundraising (figure 29). The light brown color of the notebooks’ covers reminds one of earth, the land. This subject was a central concern for Cooking at the Front Line. The notebooks also include illustrations, poems, and phrases that comment on land and housing issues. There is a clever juxtaposition of sound-alike Taiwanese and Mandarin phrases captioning the small illustrations that, while obvious to those fluent in both Taiwanese and Mandarin, is lost on the non-Taiwanese speaking Chinese KMT settlers and the average Occidental reader. For example, the first half of the titles, “My house, no place,” and “My rice field, no property” are in Taiwanese, and the second half is in Mandarin. The two small drawings, one of rice plants and the other of a damaged building baring its concrete and rebar, match the two phrases and symbolize two distinct periods of Taiwan’s history: the pre-industrial, agricultural period and the wave of demolition during present-day urban redevelopment (figures 29 and 30).

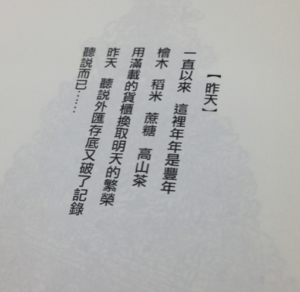

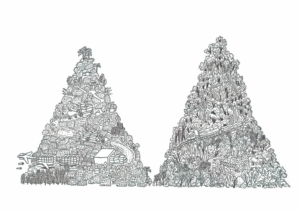

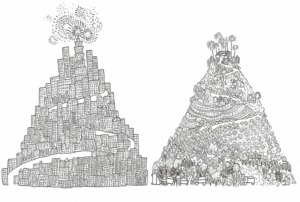

Two poems composed by the students for the notebooks further illustrate Cooking at the Front Line‘s critique of Taiwan’s contemporary values, land policy, and lifestyle. The first poem, “Yesterday,” reads: “As it has always been, every year is harvest year: cedar, rice, sugar cane, high mountain tea; exchanging containers full of goods for tomorrow’s prosperity. Yesterday, I heard we broke the foreign exchange reserves record again. I simply heard through word of mouth.” The second poem, “Today,” reads: “As it has always been, we always relinquish mountains, forests, rivers, and streams to corporations; rich farming land exchanged for concrete buildings. Parents sent to nursing homes, children entrusted to kindergartens, youthful years mortgaged to banks. We concede all limited resources until we lose our foothold.” These poems contrast two ways of lives. In the past, people made a sustainable and profitable living by working the land. In the present society, family life has become fragmented, and natural assets are exploited to cause financial hardship for many. Two detailed, black and white drawings in the notebook visualize the “Yesterday” and “Today” poems. They depict four mountains, with three representing “Yesterday” and one representing “Today” (figures 31–33).

The illustrations portray agricultural products, rice, cedar, and tea being grown and transported by plane, train, and trucks for export (figure 32 and mountain on the right of figure 33). Atop the mountain at the right side of figure 33, one can see the san ho yuan, the typical residential architecture in agricultural Taiwanese society. Beetle nut trees, common to the country, surround the living complex. In contrast, the mountain on the left side displays a mountain overtaken by high-rise buildings (figure 33). A New Year’s Eve firework display from the Taipei 101, a landmark skyscraper, crowns the mountain top. Trees exist only sparsely along the main road. The illustration of the poems deepens the understanding of the texts.

Whether through playful charm or combative stance, Cooking at the Front Line applied a unique approach to protest. Through the making and sharing of food, this group transformed a space of hard struggle, trauma, and antagonism into a softer place of creativity, nurturing, and fellowship. For members of Cooking at the Front Line, their artistic practice became a way of sharing and critical reflection. Kiln construction, packaging designs, posters, new recipes, and handmade utensils were central to a dialogue on land and housing equity. More importantly, these creative elements spurred participants to reconsider the meaning of art in everyday life. Through interdisciplinary collaboration, Cooking at the Front Line merged art and social activism with everyday acts. Social activists and supporters rallied for urban equality as they enjoyed food in a space of contestation.57

Conclusion

In the struggle against a neoliberal Taipei, its citizens persisted. Protest art became a prominent element of Taipei’s housing rights movement. Notably, jovial and contentious tones coexisted in Taiwan’s protest art and housing rights movement. Moreover, the working dynamics of Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line transcended social, cultural, and economic differences. Foremost, the participants identified as “citizens.” They exercised and defended a “right to the city” as they resisted forced demolitions of homes and communities. These citizen-activists challenged the neoliberalization of Taipei through everyday activities. Ordinary acts, such as driving and cooking, became powerful performative gestures and protest statements. Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line also drew inspiration from multiple cultures for its content and artistic expression. They reflected an appreciation of Taiwanese history and culture, as well as a knowledge of regional and global cultural trends, such as German and Mexican history, as well as Japanese popular culture.

Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line demonstrate that participatory art can produce significant social and artistic commentary while embracing its interpersonal and collective aspects. At the same time, their more nuanced and complex approaches require a broader interpretive framework. The housing rights movement in Taipei often combine concrete art objects with performances and social activities. Artistic craftsmanship and the artists’ interest in discursive, interactive collaboration are both evident, and the intention of individual works can be multi-dimensional, varied, and distinct. For instance, good will, the desire for collective action, social transformation, and an increased understanding of specific communities, as well as a critical antagonism that scrutinizes governmental policy and educates the public, all characterize Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line. These protest artworks rely on active audience participation to create aesthetically sound pieces that form powerful social critiques of past and present urban development schemes. They also illustrate a broader definition of participatory art, as a genre that not only depends on but can also be initiated by the general public.

From 2010 to 2013, participatory art played an important role in facilitating the reexamination of Taipei’s neoliberalist urban development. This artistic approach allowed artists and participants to envision, to demand, and to enact change into existing politico-economic establishments. In Taipei’s housing rights movement, the alliance of activists combined different art forms to spread the same political message: the need for more transparency, equality, and citizen participation in urban governance. The interdisciplinary and collaborative nature of Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line leads to a fluid interpretation of participatory art. They indicate that this artistic genre comprises diverse adaptations rather than a defined set of parameters. These works illustrate that conviviality and criticality can coincide in participatory art. Moreover, they affirm participatory art’s ability to agitate problematic dynamics in the (re)construction of cities in the globalized present.

Notes

- David Harvey, Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (London/New York: Verso, 2012), 67. ↩

- Jamie Peck and A. Tickell, “Neoliberalizing Space,” Antipode 34, no. 3 (2002): 380–381. ↩

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “A Fragmented Globality,” in Global Transformations: Anthropology and the Modern World (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 53–54. ↩

- Peck and Tickell, “Neoliberalizing Space,” 380–381. ↩

- Pierre Bourdieu, Firing Back: Against the Tyranny of the Market II (New York: New Press, 2003), 34–35. ↩

- Catherine Kingfisher and Jeff Maskovsky, “The Limits of Neoliberalism,” Critique of Anthropology 28, no. 2 (2008): 115. ↩

- Gordon Fletcher, The Keynesian Revolution and Its Critics: Issues of Theory and Policy for the Monetary Production Economy (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 1989), xix–xxi, 88, 189–191, 234–238, 256–261; Peck and Tickell, “Neoliberalizing Space,” 380–381; Lee Zong-Rong, “Taiwan’s Intercorporate Familial Network” (台灣企業間的親屬網路), Academia Sinica Weekly 1261 (2010). ↩

- Lee’s Chinese name is 李宗榮; Academia Sinica, or 中央研究院, is Taiwan’s most preeminent academic institution. The Chinese phrases for political emancipation and economic liberalization are 政治解放 放鬆管制. “We are Family,” interview with Lee Zong-Rong, ed. Kao Jun-Honn (Tainan: Tainan National University of the Arts, 2010), Act 03, 8. ↩

- The Chinese names for these three families are: 高鐵, 遠傳, and 台灣大哥大 respectively. ↩

- Lee, Act 03, 8. ↩

- Huang and Chang, “The Grand Families”; Lee Zong-Rong, “Taiwan’s Intercorporate Familial Network”; David Skarica, The Great Super Cycle: Profit from the Coming Inflation Tidal Wave and Dollar Devaluation (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2010), 208. ↩

- Huang and Chang, “The Grand Families of Taiwan.” ↩

- Lee, Act 03 , 8 ↩

- See Huang Ching-Hsuan and Chang Hsiang-Yi, “The Grand Families of Taiwan,” CommonWealth Magazine 462, https://english.cw.com.tw/article/article.action?id=923, December 16, 2010; also Lee, Act 03, 9. ↩

- Harvey, Rebel Cities, 67. ↩

- “1989-2014 Urban Housing Movement (Shell Less Snails Movement)” 1989–2014 都市住宅運動(無殼蝸牛運動), National Taiwan University, Graduate Institute of Building & Planning. http://www.bp.ntu.edu.tw/?p=3290, accessed October 23, 2018; 陳雅雯. 十年蝸牛路的成績單—專訪無住屋者團結組織理事長李幸長.《破週報》復刊第65期, June 25, 1999. ↩

- The Lo-Sheng Sanatorium controversy began in 1994, when Taipei City Government designated the Sanatorium premise as the building site of the future Hsinchuang MRT Maintenance Station (新莊機廠). Since then, the residents and supporting students formed Lo-Sheng Preservation Self-Help Association and Lo-Sheng Youth Alliance, respectively. These two groups rallied for the Sanatorium’s preservation, citing its historic significance, environmental risks posed by construction plan, and the housing rights of the elderly residents to remain in a familiar, convenient living space. After the partial demolition, these pro-preservation groups continued their efforts, and finally on December 22, 2016, after petitions outside The Control Yuan and The Executive Yuan, the National Development Council approved a proposal that would modify current construction plans to five fewer train tracks. This decision “gives grandpas and grandmas at Lo-Sheng hope of returning to their familiar homes.” 吳旻娟 (Wu Min Juan), 「過去的錯誤不該延續!」 樂生成功爭取重建平台 (“Mistakes from the Past Should Not Persist! Lo-Sheng Fight for Rebuild Platform a Success”), PTS News Network, December 22, 2016. Reporter’s English name and the article’s English title are the author’s translation. ↩

- Suzana Milevska, “Participatory Art: A Paradigm Shift from Objects to Subjects,” Eurozine, 2006, http://www.springerin.at/dyn/heft_text.php?textid=1761&lang=en; Rudolf Frieling, The Art of Participation: 1950 to Now (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008), 12; Claire Bishop, “Claire Bishop and Boris Groys on Participatory Art,” Tate Modern, May 1, 2009, https://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/bring-noise. ↩

- Claire Bishop, “Introduction,” in Artificial Hell (New York: Verso, 2012). ↩

- Kester, Conversation Pieces, 79; Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics; Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004): 51–79; Hal Foster, “Chat Rooms” (2004), published as “Arty Party” in London Review of Books, December 4, 2004, 21–22; and Suzi Gablik, “Connective Aesthetics: Art After Individualism,” in Mapping the Terrain, 74–87; Suzanne Lacy, “Debated Territory: Toward a Critical Language for Public Art,” in Mapping the Terrain, 171–187; and Leonie Sandercock, “The Death of Radical Planning: Radical Praxis for a Postmodern Age,” in Cities for Citizen: Planning and the Rise of Civil Society in a Global Age, ed. Mike Douglass and John Friedman, (Chichester, NY: Wiley, 1998), 423–439. ↩

- Bourriaud. Relational Aesthetics, 15, 22. ↩

- Bishop, Artificial Hell, 2. “Heavy metal art,” public art made of metal or other industrial materials, is a term that refers to traditional art objects installed in public spaces. Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 11–31; Claire Bishop, “The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents,” Artforum, 179–180. ↩

- Foster, “Chat Rooms”; Participation, 190–194. ↩

- Shannon Jackson, “Living Takes Many Forms,” in Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991–2011, ed. Nato Thompson (New York/Cambridge: Creative Time/MIT Press, 2012), 93. ↩

- In Artificial Hell, Bishop criticizes “the instrumentalization of participatory art as it has developed in European cultural policy in tandem with the dismantling of the welfare state.” She notes that the UK under New Labor (1997–2010) “embraced this type of art as a form of soft social engineering,” and mentions the critique of New Labor’s encouragement of social inclusiveness in art because “it seeks to conceal social inequality, rendering it cosmetic rather than structural.” Thus, participation for New Labor “referred to the elimination of disruptive individuals.” Bishop, Artificial Hell, 5, 13. ↩

- Lacy, “Introduction,” in Mapping the Terrain, 19–48. ↩

- The introduction and analysis of Operation Little Barbarossa and Cooking at the Front Line provide artworks outside the other authors’ current geographic consideration. The examples in Frieling’s The Art of Participation, Bishop’s Artificial Hell, and Thompson’s Living as Form, the three most recent and comprehensive examinations of participatory art, focus on the European context. ↩

- Nato Thompson, ed. Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011 (New York/Cambridge: Creative Time/MIT Press, 2012), 26–27; 249–250; 256. ↩

- Quoted from the then Minister of the Interior, Chen Wei-zen (陳威仁), as reported by Alison Hsiao, “Assembly and Parade Act Scrutinized,” Taipei Times. March 18, 2016. www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2016/03/18/2003641862. The same article stated that Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator, Cheng Li-chun (鄭麗君), re-proposed amendments to the Act after a failed final reading due to a Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) boycott. And another DPP Legislator, Lin Shu-fen, called for its abolition all together. The Assembly and Parade Act became a focus in the 2008 Wild Strawberries Movement (WSM). Active from November 6, 2008 until January 6, 2009 and as a response to this student movement argued that the Assembly and Parade Act was unconstitutional. The Movement’s staff members rallied for its immediate amendment. See Yen Chia Chi,“Wild Strawberry Movement- A Milestone of Taiwan Social Movement,” July 14, 2013. Personal blog, accessed December 17, 2018. http://kateyen.weebly.com/blog/wild-strawberry-movement-a-milestone-of-taiwan-social-movement For detailed accounts of the WSM’s emergence, see the Movement’s blog (in Mandarin Chinese), “Wild Strawberry Movement Action Satement” http://action1106.blogspot.com/2008/11/1106_7181.html The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees the right to freedom of assembly, which appears in almost all democratic constitutions. And the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, Article 12 protects people’s right to “freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association at all levels, in particular in political, trade union and civic matters” (http://fra.europa/en/charterpedia/article/12-freedom-assembly-and-association). However, from 2012 to 2015, this democratic promise of freedom to assemble has been reversed, with Quebec, England, France, Australia, Spain, Turkey, the US passing laws to make public protests punishable. Egypt, Ukraine, and Russia have outlawed protest all together. See “Countries around The World Are Revoking Freedom of Assembly,” Al Jazeera America, May 4, 2015, http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/5/countries-across-world-are-revoking-freedom-of-assembly.html ↩

- Kao Jun-Honn, ed., act 02 (Tainan: Tainan National University of the Arts, 2010), 2. ↩

- The original Chinese title for “There are Plants in the Parks; There are No Houses for Citizens” is 公園有草木, 市民沒房住. Yang Kai-wen, act 02, 4–5.The article accuses the government of selling state-owned lands’ usage rights cheaply to financial groups, which “steal” potential public spaces for future generations. Yang, the author of the article, belongs to “Take a Good Look at Taipei, Eighteen-Month Fake Parks,” a group that staged its own protests. See https://www.facebook.com/fake.park. ↩

- 小ACT sent two volunteers to investigate the incentives and commercial interests behind this policy. The volunteers surveyed ten areas that had been transformed into green spaces under the Taipei Beautiful policy. Their findings revealed that these lots, by now all owned by various firms, provided minimal public benefits, such as pedestrian passing for open space. At the same time, they had maximum potential for constructing buildings ranging from sixteen to forty-six levels. ↩

- Interview with Kao, June 23, 2012. Kao explained that according to regulations, structures that lack official historic status, like the Japanese houses, can be torn down at any moment. ↩

- The February 28 incident and the subsequent White Terror during Taiwan’s martial law period made the questioning of governmental policies taboo. For a detailed account of Taiwan’s history in cultural heritage preservation, see Lin Hui-Chun, “A General Introduction to Taiwan Cultural Heritage,” Encyclopedia of Taiwan, Taiwan Ministry of Culture, accessed July 13, 2013, http://taiwanpedia.culture.tw/web/content?ID=723#. ↩

- Huang Jui-mao, “Fragrant Flowers or Lethal Weapon Iron Tribulus? The Sustainable Actions and Strategies Activated by the Unjustified,” act 02, reprinted from Taiwan Architect Magazine (建築師雜誌), October 2010. OURs stands for The Organization of Urban R-s, a professional organization established in 1989 that focuses on urban reforms. It emerged out of the Homeless Solidarity Alliance (無住屋者團結組織) that organized earlier in the same year. According to introduction to the organization, “R-s” could stand for Re-design, Re-Plan, Re-build, Review, and Revolution. For more information on urban reform and the homeless rights movement in Taiwan, see OURs, http://www.ours.org.tw/about; Tsuei Ma-Ma Foundation For Housing And Community Services, http://www.tmm.org.tw/English/about_EN.htm; and Formosa, Tsuei Mama and Urban Reform Organization, “Grade Report for Ten Years of the Snails’ Journey: An Interview with Homeless Solidarity Alliance Chairman Li Hisng-long,” reprinted from Pots Weekly (破週報) 65, June 25, 1999, http://bbs.nsysu.edu.tw/txtVersion/treasure/tmm/M.855789194.D/M.872869045.A/M.930843686.A.html. ↩

- Huang, “Fragrant Flowers,” 13. ↩

- Huang, Fragrant Flowers, 13–16. ↩

- See Rosalyn Deutsche, “Uneven Development: Public Art in New York City,” October 47, no. 10 (1988): 45; Sharon Zukin, The Culture of Cities (Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell, 1995), 7–8; Malcolm Miles, Art, Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures (Abingdon: Routledge, 1997), 105. In the past fifteen years, aggressive government endorsed urban (re)development schemes have been rampant in Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, and Korea. The number of ineffective “revitalizations” that disregard the environment and local residents exceed positive instances. According to Kao Jun-Honn’s research, the homelessness issue is also critical in Japan. ↩

- Huang refers to primary information released by a real estate professional, providing evidence of a near 63 percent increase in housing market’s unit price (from 500,000 NT to 800,000 NT per square meter). Kao, act 02, 14. ↩

- For more ecological and economic arguments against the Flora Exposition, see Huang, “Fragrant Flowers,” 13–16, 2010. ↩

- Alexander Canduci, Triumph and Tragedy: The Rise and Fall of Rome’s Immortal Emperors (Millers Point: Pier 9, 2010), 263. ↩

- Jun-Honn Kao, 2011. “Artist Blog,” accessed September 14, 2014, http://bcc-gov.blogspot.com/2011/10/blog-post.html. ↩

- Interview with Kao Jun-Honn, June 23, 2012. ↩

- Interview with Kao Jun-Honn, June 23, 2012. ↩

- Interview with Kao Jun-Honn, June 23, 2012. ↩

- Although the protest action took place in Taipei, its video footage was later included in a group exhibition titled, “Bio Image” in Tainan, southern Taiwan. Chen Kai Huang, a conceptual artist and a professor at (currently President of) National Taipei University of the Arts, curated the show. ↩

- Bishop, Artificial Hell, 6–7. ↩

- “Sanying Tribe Self-Help Alliance Blog,” 2013, accessed September 14, 2014, http://sanyingtribe.blogspot.tw/. ↩

- For an updated list of TAVUR’s activism, please refer to its official Facebook page: “TAVUR Taiwan Alliance for Victims of Urban Renewal 台灣都市更新受害者聯盟,” https://www.facebook.com/TAVUR.tw/?tn-str=k*Fgfg ↩

- Interviews with Peng, Huang, and Chen, July 19, July 25, and September 8, 2012, respectively. ↩

- 料理最前線 is the Mandarin title for Cooking at the Front Line. ↩

- Although Cooking at the Front Line featured local produce, this initiative has no ties to Taiwan Rural Front, an agricultural movement. Later, some collaboration and exchange helped the two groups befriend one another. Online conversation between author and Huang Huiyu, September 23, 2018. For detailed accounts of the various site visits, food sources, and cooking methods, see the Cooking at the Front Line blog, February 27, March 4, April 21, and September 24 entries, http://cooking-at-the-front-line.blogspot.com/?m=1. ↩

- None of the Cooking at the Front Line members had culinary training. Three had an arts background, including two art students and a full time art practitioner. Online conversation between the author and Huang Huiyu, November 9, 2018. ↩

- Pikachu is a yellow pocket monster from Pokémon. Pokémon is a Japanese media franchise that includes video games, anime, and film. ↩

- According to Huang Huiyi, Pussy Riot may have influenced individual members; however, Marcos was the main inspiration for the collective. Author and Huang’s online exchange, September 23, 2018. ↩

- Online exchange between Huang and author, September 23, 2018. ↩

- On March 14, 2014, the newspaper Apple Daily reported that the Wangs’ second generation land owner Wang Yao De self-demolished the temporary hut and agreed to Leyoung Construction Limited’s urban regeneration scheme. “士林王家今自拆組合屋 引爆衝突,” Apple Daily, March 14, 2014, https://tw.appledaily.com/new/realtime/20140314/360027/. ↩