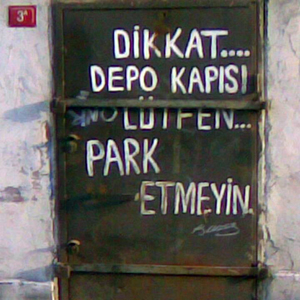

It is quite common in cities across Turkey for ordinary people to write such statements on the walls of buildings. By doing so, they communicate their requests, wishes, and sometimes their anger. What makes this one distinctive is the signature of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, sprayed below the text by an another anonymous passerby. One can run into Ataturk’s signature in different urban settings—schools, monuments, or hospitals—adorning his countless aphorisms which usually glorify the Turkish nation. Yet, never in the form of what we can call an ‘urban intervention’. Here, I am not going to delve into a discussion of how acts of detournement, such as this one, gain political significance.

What interests me in this image in relation to Alexander Dellantonio’s Urban Interventions series is that it clearly demonstrates that shared urban walls produce a sense of publicness through continuous acts of collage and decollage. Walls are contested and negotiated spaces of encounter where people communicate with each other—from their intimate feelings to agitational revolutionary slogans. This is why the powers that be want to take total control of urban space through the implementation of laws and regulations and the development of techniques and technologies designed to shorten the life of such interventionist practices. After all, public space should be planned and regulated, and it should be orderly and safe.

Political and social movements must continually claim their presence in public space, if they ever are to be seen and heard. One of the main aims of dissident movements is to occupy public space and retrieve it from the Colonisation of capital and political authorities so as make it an open space for all. In this quest for emancipation, walls appear to be one of the sites of struggle where the confrontation takes the form of graffiti, stencils, stickers, murals, posters, and the like. Yet, such inscriptions are always tainted by ephemerality. In order to counter their transient existence, activists deploy different tactics.

There is an almost forgotten tactic in the long history of flyposting. You break a couple of light bulbs, mix them with glue and then plaster your posters wherever you want them. Broken light bulbs make it difficult to remove the posters. The hope is that this practice can also deter the authorities from removing the posters. It seems like the new generation of activists and street artists have developed different strategies for prolonging their interventions, such as using durable chemicals as well as documenting them by taking photographs. The Urban Interventions series can be seen as yet another way of making street art endure.

The Urban Interventions series consist of collages of urban word—and image—scapes (posters, graffiti tags, newspapers, advertisements). The desire is to preserve the ephemeral by fixing whatever remains from the street on a manageable surface. We can read this act of preservation as a humble attempt to make sense of street politics and poetics, archiving the traces of what was once there. However, it seems to me that this urge to capture the potentially passing in such a manner misses the very politics of the street: a politics based on a constant struggle that produces alternative and unanticipated meanings. The writing on the building adorned with the signature of Ataturk is a good case in point for such struggles, where the concerns of the common clash with those of a public taboo. The everyday world confronts the official world and opens up a third level of understanding that offers an estranged vision of both of them. This clash between heterogeneous elements (and violently separated worlds-of life and arts, aesthetics, and commodities) is indeed the basic tenet of the aesthetics and politics of the collage—from Braque to Dada all the way to the works of Martha Rossler and Barbara Kruger. In such works, a dialectic between the heterogeneous parts opens up the space of the ‘interval’, which is the realm of shock and provocation, and of thought. In Urban Interventions, it seems rather like the collage form produces a homogenous and cohesive unity between the assembled pieces (tags, manifestos, leaflets, newspaper cuttings, and advertisements). The pieces suspend the act of confrontation so dear to the politics of collage in favour of representing the dissident’s voice and visuality. Theodor Adorno once criticized ‘committed art’ for bleating what everyone is already saying or at least secretly wants to hear. This is why, for him, such art runs the risk of becoming an empty slogan and preaching the converted. In a similar vein, when we see the manifesto with the title “battaglia communista” for example, our hearts may move a little faster, but it does not necessarily provoke us to think or act.

One must admit that there is something politically motivating about the Urban Interventionsseries, as it brings together bits and pieces of ‘signs’ of comrades in other parts of the world. It makes you feel like the movement is indeed everywhere. Yet, the series also shows us that we should try to find ways of making sense of our struggles beyond the limits of representation. Experimenting with creative ways of fabricating antagonisms on canvases is as revolutionary as producing them in the streets.