Introduction

In the face of the COVID-19 global health pandemic and intensifying barriers to life—isolation, poverty, loss of supports, and the devaluing of autistic lives—the Re•Storying Autism Collective (hereafter the Collective) began meeting online during the spring of 2020. The Collective is a group of autistic and neurodivergent artists, students, co-researchers, makers, and critical allies across northern Turtle Island (Canada) who gather to cultivate online autistic community, create activist art and advise on, develop, and lead research.1 Re•Storying Autism is an international research collaboration between autistic and non-autistic community members, artists, researchers, family and kin, educators, practitioners, and critical allies working for disability justice in education, broadly conceived. It is led by neurodivergent researcher Patty Douglas.2 Disability justice is a political, arts, and intellectual movement of Black, brown, queer, trans, and disabled people that “means that we are not left behind; we are beloved, kindred, needed.”3

As the pandemic began to restrict our lives, the Collective started to dream together during our monthly online meetings about making neurodivergent art and telling autistic stories that might help us connect, survive, and thrive. We found ourselves facing heightening barriers that have long marked non-normative lives for exclusion and, as philosopher Achille Mbembe tells us, even death (both figuratively and literally). Mbembe describes the late modern impulse to systemically contain individuals and groups that fail to embody the valued autonomous, productive individual as necropolitics, “new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to living conditions that confer upon them the status of the living dead.”4 It is Black, brown, poor, disabled, global South and other non-normative lives that are subjected to such living conditions. Whether through exclusion (be it from life-saving treatment during a global health crisis, or education, employment, and arts spaces), curative therapies, or murder (by our caregivers or by police), our humanity and personhood have long been denied. Through misunderstanding and distorted media tropes (such as the lost or stolen child, the savant, or autistic people as dangerous),5 our authority to tell our own stories has been questioned or forbidden.6 The pandemic laid bare these realities in the starkest of terms.

Making Outsider Art: Cultivating Crip Community through Radically Inclusive Praxis

The idea to facilitate a zine-making workshop with autistic makers emerged when Collective member Kat Singer suggested digital zines as the perfect medium to express autistic pandemic experiences and to push back against the loss of supports and community that we were experiencing. Zines (short for “magazines”) are a DIY (do-it-yourself) pamphlet-like type of art that often document experiences of marginalization and push back against power. This form of DIY publication has a low barrier for entry as it can be entirely handmade (and then photocopied or scanned for distribution) and can feature a wide range of media (pen and ink, collage, typed or handwritten text). Content comes in many forms (comics, poems, essays, illustrations etc.).7

We chose the medium of digital zines in particular for its flexibility. It gave us a way to support makers who were remote during a pandemic and who may or may not have had access to art supplies and/or artistic support for hand drawn work. A digital medium also opened ways to widely share zines through online networks (websites, online exhibits) while also retaining the possibility to print them for future in-person exhibits. The digital medium and format also align with preferred ways to be in community such as blogging and online gaming.8

During the fall of 2020, the Collective planned, organized, and facilitated a seven-week online zine making workshop series. We invited sixteen autistic makers and artists sixteen years of age and over across northern Turtle Island to artfully express and challenge the dehumanization and devastation, as well as the possibilities we/they were experiencing. This workshop series was led and facilitated by autistic members Kat Singer, Sherri Liska, and Besa Shemovski Thomas (with contributions by Steacy Easton and David Preyde), who developed and delivered a zine-making curriculum including tutorials on the artistic and technical aspects of creating a zine online. We share an image below (Fig. 1) from our zine-making curriculum to familiarize any unfamiliar reader with what a zine is, and to bring them closer to the feel of the activity that took place in our workshop in the midst of a global health pandemic.9

As the Collective planned ways to create accessible online space for participants, we identified core values that would animate the space, including radical access, flexibility, and relaxed ways of taking part. We drew inspiration from activist histories of outsider and disability arts10 as well as from disability justice, critical digital pedagogy and Relaxed Performance.11 Critical digital pedagogy puts justice at the centre of any approach. As Stommel, Friend, and Morris put it, critical digital pedagogy “reclaim[s] the critical aims of education, its questioning and reflection, its imperative toward justice and equity, and its persistent need to read the world within which it takes place, whether that’s a classroom, a livingroom, a playground or a digital device.”12 As a collective, we critically “read” the online space for radical access opportunities. Relaxed performance, a movement started by autistic community in the 1990s to welcome all bodies and open access to theatre and the arts by challenging norms such as stillness and silence during performances, also shaped the terms of our workshop space. Below is our infographic, “Accessible Online Space,” (Figs. 2–3) that we created and shared with participants. It makes our commitments and orientation to radical access concrete (see paragraph below for more on radical access). It was generated through the Collective’s many discussions of how to set the terms of online space beyond an accessibility checklist alone, and, at times, across conflicting access requirements (for example, staying on schedule versus crip time, an orientation to time that moves with the needs and desires of those present in the workshop).13

By radical access we mean that we strove to identify and eliminate barriers to access in a variety of areas—finances, technology, communication, skills, trauma, and more—through built-in supports including but not limited to covering the purchase of design software Canva Pro, paying a modest stipend to participants for their time, and providing digital downloads of all synchronous tutorials and group sessions. We also invited participants to set up one-on-one creative or supportive sessions with facilitators of their choice and embraced participants’ preferred communication styles (speaking, typing, emojis, or even none at all), intentionally creating text-accompanied, unambiguous, visually organized, yet relaxed presentations. Further, we provided suggestions and guidelines for participants to maximize the accessibility of their digital works for their viewers (e.g., image descriptions, high contrast text). Sherri Liska led the Collective’s access initiatives and wrote a guide including these elements for workshop participants.14 After the workshop series was over, we held a one-hour focus group with interested participants about how the workshop design and our efforts around radical access were experienced by participants and lived on in people’s lives. We learned that the online workshop series, by bringing autistic makers together virtually, opened unique pathways to cultivate autistic community (for some participants, this was their first time being in autistic space led by autistic people), extended disability arts/neurodivergent arts networks in Canada, and, for some participants, led to the launch of their own art exhibits.

At the same time, the radical access we worked to cultivate in our online workshop series had limits. Technological, material, and other frictions arose during the workshop series in the sense that Hamraie and Fritsch write about in “Crip Technoscience Manifesto,” where they describe “access-making as a site of political friction and contestation.”15 Despite our collective efforts, we were unable to eliminate all of the material, structural, or technological barriers makers faced. Recognizing that access is not a checklist that, once satisfied, can guarantee access for everyone in every context, we endeavoured to use moments of friction generatively and reflexively to advance disability justice. By providing one-to-one supports, pausing in the flow of the workshop to slow it down or hold space, revising our schedule, or using the private chat function during large group meetings, facilitators worked as “access doulas” to collectively bring access into being as the workshop series unfolded.16 For example, we encountered a number of technological challenges. Some makers were not able to resolve issues with Canva Pro on their own by using our video tutorials or through screen sharing during group meetings. Some of these challenges were resolved during one-to-one meetings with facilitators, but we did feel in the end that in-person options would have helped some makers to better achieve the visual effects they had in mind. This was a limit of COVID-19 and the geographic spread of our workshop series. Some makers who identified as multiply disabled also told us that even though they had been making zines for years, they almost did not sign up for the workshop because they were worried about learning Canva during a pandemic over a limited number of weeks online. So we wonder about the makers who were not there, and what other supports and options (such as sending concrete materials to people at their homes or making a greater variety of video tutorials) we could have provided. We also faced access frictions in terms of scheduling. To offer flexibility to makers who worked or had other commitments during the day, we varied meeting times to include some evening meetings. This posed challenges for others who found it difficult to adapt to a changing schedule from week to week. To find ways to navigate this, we offered one-to-one meetings at preferred times set by makers, a visual schedule well ahead of the workshop series and regular email reminders. We also had open conversations about access frictions in our large group meetings and collectively recognized access as ongoing and always incomplete.

Another access friction emerged around the legacy of whiteness in autistic identity/diagnosis and community. An autistic person of color in the workshop raised the issue of feeling uncomfortable in a group that appeared white. The lead facilitator at the time, Patty Douglas, attempted to hold space for and affirm this makers’ experience, but ultimately failed to provide a sense of belonging or access for this maker. Another facilitator also reached out through private chat, and Patty reached out by email afterwards. Ultimately, this maker chose not to complete the workshop series, reflecting our team’s failure to fully redress the legacy of whiteness in autism diagnosis, identity, and self-advocacy, despite our recruitment efforts (including specific recruitment calls for participation by autistic makers of color as both facilitators and participants) and efforts to affirm and hold space. We have reflected deeply about this moment of failure and unresolved access friction. Many autistic people of color took part in the interviews we held in parallel to the zine making workshop, and so we wonder what other barriers related to white supremacy and/or class we may have reproduced in our workshop design, whether this was the intensive time commitment required, the workshop focus, the university research ethics’ limits on participant financial compensation, the nature of our newly developing relationships with autistics of color or Indigenous autistic makers, or some other reason. Since the zine making workshop, Douglas has focused much of her research time on decolonizing stories of autism. She has formed reciprocal relationships with Māori community leaders in Aotearoa (New Zealand) and Indigenous organizations in Manitoba, Canada, and has held Re•Storying workshops (multimedia video making) on topics such as Indigenous approaches to autism identified by these communities as priorities. Like for the zine workshop, Douglas has acted in the role of holder of space and helper from the sidelines from her position as a neurodivergent university faculty member. This work, too, is always incomplete and ongoing.17

The Images

We include here images of artistic work from zines created in our online workshop series. Singer, Liska, and Douglas co-curated this collection of images with artistic and technical support from project coordinator and artist Sheryl Peters. To choose the images, we gathered in person (after COVID restrictions lifted) with physical copies of the zines, read through them together, and weighed a number of factors including aesthetic appeal, visual impact, affective content, thematic content, and representation (e.g., zines by diverse autistic makers in terms of gender and sexuality, multiple disabilities, professional artists versus first-time makers, etc.). Image descriptions were also co-created, staying as close as possible to makers’ own words offered in their artist statements. We believe the set of images we curated reflects creators’ common experiences. We group images into four themes: “COVID Isolation and Barriers”, “Masking and Unmasking During COVID-19,”18 “Humor as Resistance,” and “Autistic Community and Hope.” More broadly, the themes are also resonant with our co-analysis of thirty-five interviews held alongside the zine-making workshop with autistic makers across Turtle Island.

We invite readers to spend time with the images, descriptions, and text. In keeping with zines as outsider art and our collaborative approach, we do not perform an in-depth academic analysis here,19 although our image descriptions, informed by the work of blind scholar Hannah Thompson and blind artist Jessica Watkin on image description as its own artful practice, include interpretative and affective analytic elements.20 We invite readers to document their thoughts and feelings on a collaborative “Autistic, Surviving and Thriving” page (click on “Read More” and enter the password: zines). The questions we ask viewers to consider are artful ones often used by Re•Storying during viewing events on the project, “What is it that the makers are asking us to see, feel or sense that might be new? How do the stories touch and move us?” “If you could ask the zine maker a question, what would it be?” We also offer a gentle content warning. The images presented reflect a full range of experiences under COVID-19, from connection, celebration, and joy to pain and distress. We invite you to practice what we call a care-full neuro-crip viewing—reading slowly, skipping over pages, having a comfort item close by, reaching out to someone you trust, stimming (repetitive movements), or something else that makes you feel good.

COVID Isolation and Barriers

Isolation was a prominent theme across the zines made in our workshop series. In the set of images we curated for this section, the beholder encounters the disconnection and overwhelm of unpredictable pandemic restrictions and rapid adaptations like Zoom.

Em Farquhar-Barrie’s “Alone in the City” (Fig. 4)—unexpectedly detailed for a piece drawn in only black pen—depicts a twisted, distorted cityscape in which the artist feels lost, alone, and powerless. In the foreground, nameless and numberless buildings jut and tilt in various directions. Some have flashy, decorative, but abstract entrances; others are made of simple brick or only windows. Some are three-dimensional; some are flat. The buildings are crammed next to and in front of each other, and the features of each are dense and sketchy, evoking a sense that this city is boundless, untraversable, and impossible to comprehend. In the background, much taller office buildings fill the page all the way to the top. Densely packed with lit windows, the giants tilt and swirl, consumed by a dark whirlpool that spirals behind one lone silhouette of a person, limply floating and faceless. Above the figure, two clouds and a few sparse stars—the only remnants of a dwindling, degrading night sky—swirl, too, into the all-consuming spiral.

Farquhar-Barrie blends pen drawings and the digitally-altered versions of those drawings into a dense and complicated collage in “Zoom” (Fig. 5). The piece represents the sensory overwhelm of a Zoom environment: we are crowded, yet alone. Pen drawings of screens, each firm-handed yet sketchy, fill the page. Blank screens, screens with faces, screens with text, screens with TV static, and screens with telephone icons overlap each other, patternless and dense, some right-side-up and some upside-down, all running Zoom. The faces are indistinguishable and featureless, speaking but never emerging. Are they omnipresent? Are they not present at all? A “TV pixel” effect overlays the whole image while a “weak TV signal” effect distorts random parts. It’s as if the artist isn’t using Zoom like the others but watching their meetings, classes, appointments, and workshops play out on television—they are disconnected, unable to participate, and alone in a sea of faces.

In Mandy Klein’s “Change, Change, Change” (Fig. 6), each instance of “change” is in a different, neon color, and all of the text glows, as if it were a blinking neon sign. The choice to use neon signs—a source of sensory overwhelm for many autistic people—helps to represent that change, too, can be deeply overwhelming.

Access for autistic and disabled people during the pandemic was often not considered by decision-makers and systems.21 Makers in this section also point to how systems separated autistic and disabled students from mainstream schooling during COVID and point to the injustice of years of pre-pandemic systemic denials of flexible learning options like online education for neurodivergent students which were so rapidly made possible during COVID-19 (see Fig. 7).

The zines in this section lay bare how necropolitics was at play during the pandemic through the targeted isolation of disabled bodies and their containment to the “status of the living dead.”22

Masking and Unmasking During COVID-19

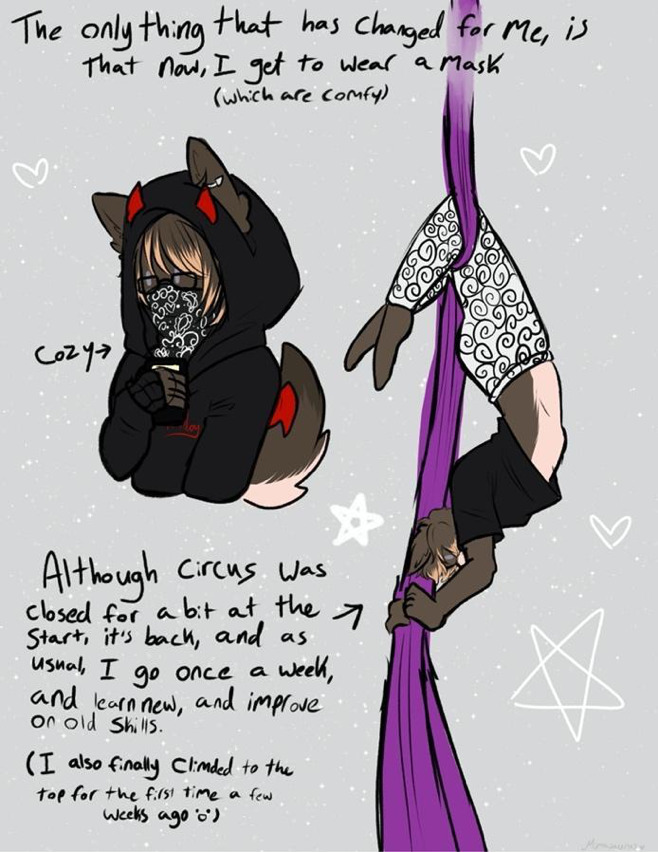

Masking is a term many autistic people use to self-describe how they/we consciously or unconsciously hide or suppress our/their unique ways of being such as repetitive movements (called “stimming”) to appear more typical and avoid stigma or discrimination. Masking is often described as painful and exhausting.23 It came up as a theme across several of the zines in layered and complex ways, pushing the conversation about disability and COVID-19 in new directions.

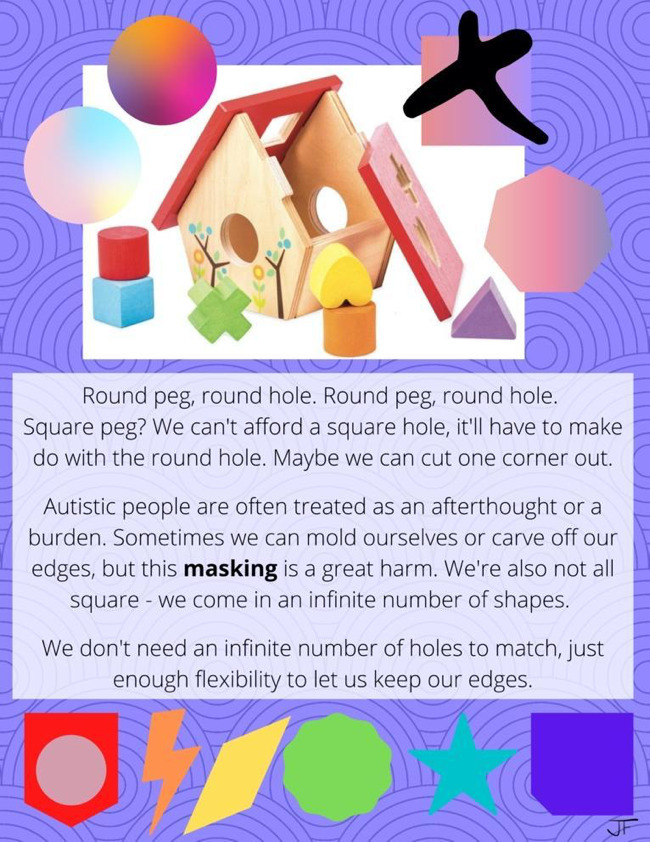

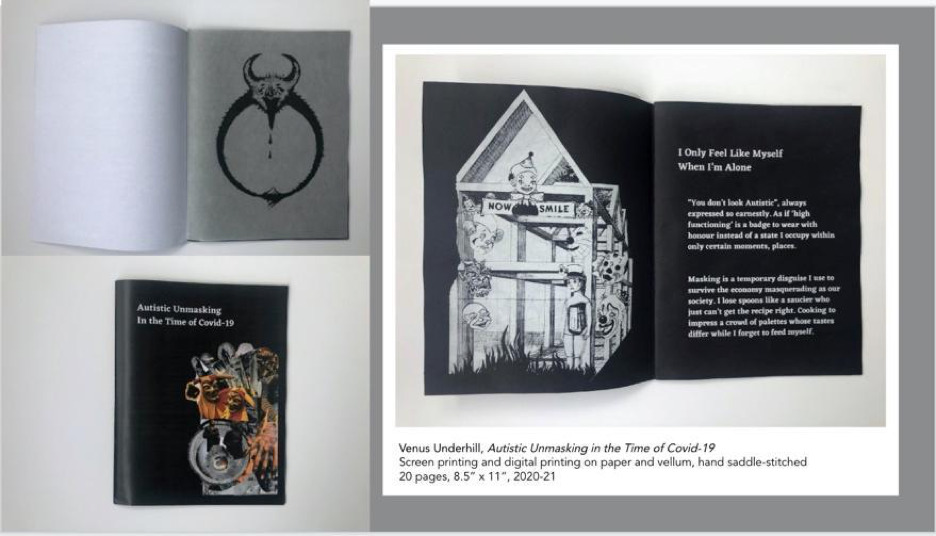

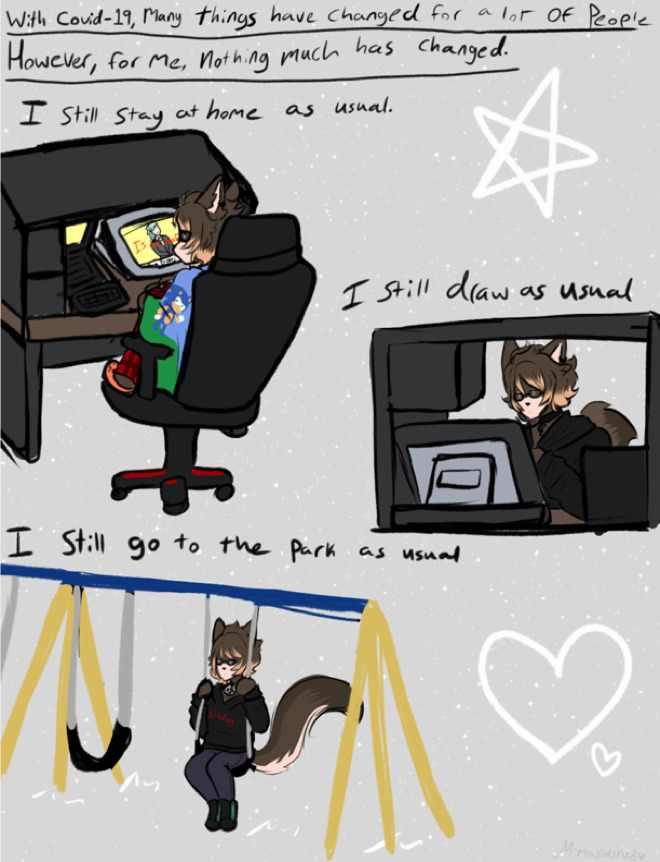

To sum up this section briefly, masking emerged in a multitude of ways across several of the zines. This plurality of articulations of masking complicates, first, assumptions around the effects of COVID-19 as solely negative or traumatic for autistic and disabled people, as in Lucabean’s assertion (Fig. 8) that “nothing much changed” and that, “The only thing that has changed for me is that now I get to wear a mask (which are comfy).” As disability justice activists point out, autistic and disabled people already hold individual and collective wisdom about how to survive and even thrive under regimes that isolate, contain, stigmatize, and marginalize those who are different.24 In some ways, COVID-19 was nothing new. As Venus Underhill articulates in Figure 9, “Covid has been isolating but masking has made me intimately familiar with isolation.” Underhill also pushes this conversation further with poetic reflections accompanying their artwork. They write, “I don’t want to preserve this diluted sense of self anymore, I’m not certain I could anyway.” Underhill seems to suggest that COVID-19 was an occasion where masking autistic ways of being could be suspended, at least for some autistic folks some of the time, given the shift to online school, work, and activities where you could turn your screen off or participate asynchronously. We do not wish to diminish, however, the pain of masking or of the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns for autistic and disabled people. Jennifer Fehr (Fig. 10) talks about the “great harm” that comes with inflexible systems and the imperative to mask embodied ways of being that are labeled autistic. In their jarring artwork, Underhill, too, alludes to the ableist imperative to mask as a kind of painful, frightening, disjointed, horror-filled “living death” (recall the image of the clown with the words “cut out” for eyes).25

Humor as Resistance

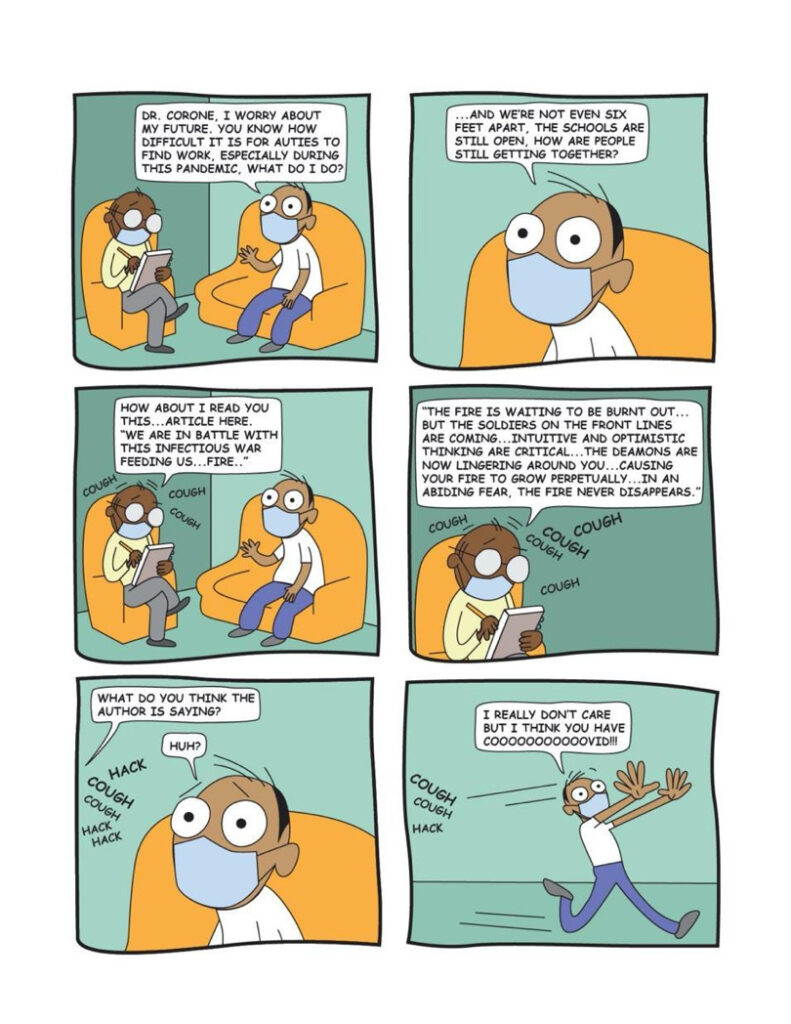

Although we share only one zine image in this section, we include humor as resistance as a theme because it was prevalent in our discussions of the zines as a collective, as well as in Rose Bisk’s comic strip (Fig. 11). Rose Bisk’s satirical artwork offers a painfully honest, larger-than-life depiction of the miscommunication that often marks encounters between professionals and autistic people, only this time, our very survival is at stake during a pandemic. The main character, the client in the scenario, rather than being other or exceptional, asks the pragmatic questions all of us asked during the pandemic about how we might find work, about social distancing and pandemic contradictions—“the schools are still open”—and what the future might hold. The professional in the scene, however, is rigidly focussed on explaining COVID-19 to the client through incomprehensible metaphor after metaphor which only serves to heighten the main character’s anxiety. The interaction in the session ends with the client exiting the scene in an exaggerated and dramatic way, and yet, the reader knows that the client is in fact the more humane, attuned, and pragmatic character. This is why the comic makes us laugh and yet it is painful, because this kind of failure of empathy is so commonly enacted by professionals with painful and life damaging effects. Through humor, Bisk in this way spotlights the dire need to attend to the humanity of autistic people during times of both crisis and the mundane.

Autistic Community and Hope

We do not offer up the theme of autistic community and hope in a naive or ideal sense. We are acutely aware that autistic community is fraught, marked by its own access frictions, hierarchies, and exclusions. For example, Tiffany Hammond, Black autistic mother of two Black autistic sons in the United States, blogs about the white supremacy of global North autistic self-advocacy and the need to expand priorities and perspectives beyond that of the autonomous, white, (often) male appearing neoliberal subject.26 Recall also from above that while the zine-making workshop was diverse in terms of gender, sexuality, and geographic location (rural, urban), it was not racially diverse in terms of leadership or participants. As described above, this in part reflects autism as an historically white, global North, and (ironically) economically privileged diagnosis/identity and the need on our project to ongoingly cultivate authentic relationships with BIPOC communities.27 We also engage hope in a critical sense to mean the hope that emerges when care and affirming embodied difference as fundamental is dispersed across a community or collective rather than located in individuals alone.28

Hannah Monroe’s zine (Fig. 12) demonstrates this critical hope and community through neighbourhood music jams during lockdown when she connected with others across social distance through music. Throughout the pandemic, Hannah tried to maintain a sense of community and meet her social needs via online paint nights. The painting shown in Figure 12 is the result of one such effort.

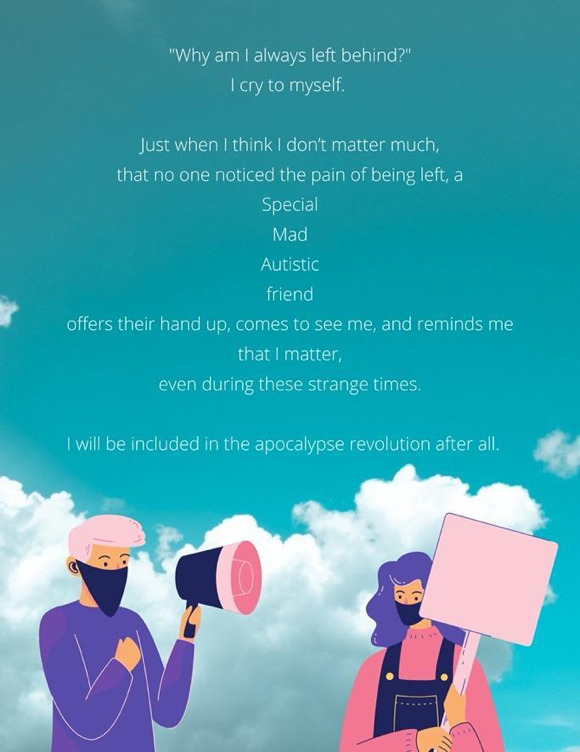

Emily Gillespie’s zine (Fig. 13) , too, enacts critical hope and the simultaneous failure and success, pain and joy, of intersectional autistic community when she writes, “Just when I think I don’t matter much, that no one noticed the pain of being left, a Special, Mad, Autistic, friend, offers their hand up, comes to see me, and reminds me that I matter, even during these strange times. I will be included in the apocalypse revolution after all.”

The zines made in our workshop series communicate lived experiences of crisis and heightening systemic and intersectional injustice. The zines also show resistance through activist art, crip community, and crip knowledges of survival (and even thriving) during crisis. They convey the forging of collective hope for radically inclusive autistic futures—what zine maker Emily Gillespie calls “The neurodivergent, Mad, accessible, Basic Income Revolution.” We believe that activist digital artmaking is a powerful way to archive, begin to theorize, feel, resist, and co-produce crip knowledge. We also believe that it allows us to dream collectively, emerging through the crisis of COVID-19.29 Activist digital zine-making opens a new, affective, and aesthetic form of resistance and creative research that calls for “forgetting” ableist capitalist colonialism and Western Enlightenment modes of subjectivity and knowledge production that target different bodies to exploit, debilitate, maim and/or eliminate.30 We use the word “forgetting” purposefully, to signal the moments and movements of creative resistance already underway in which alternate possible worlds beyond ableist capitalist colonialism surface. We contend that the zine-making workshop was one such moment; it moved us beyond the objectification and flattening of what it means to be and become human and opened a space and time to thrive together in all of our struggle, beauty, pain, and joy.31 The zine project was a gesture of hope during crisis that shows “we were here”32 and it is also a dream for future possibilities infused with crip knowledges (such as humor) and crip spacetimes (such as slowing time down and virtual community making)33 that have always been here.

What’s Next for Autistic, Surviving and Thriving?

Eleven of sixteen zine-makers took part in a follow-up initiative, working with arts educator, curator, and critical ally Tara Bursey to create exquisite physical copies of their zines. Collective members also curated an in-person and online zine exhibit that ran at Tangled Art + Disability Gallery in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, September 13–October 21, 2022. The zines in their entirety with image descriptions and artist statements based on this exhibit can be viewed on the Re•Storying Autism website.34 An open access online module focused on neurodiversity affirming approaches for scholars, educators, high school students and teachers, practitioners, clinicians, and others, using some of the zine art and more, is also underway. In addition, we are co-analyzing interviews and zines as members of the Collective to archive the making practices that provided the conditions of possibility for the cultivation of autistic community and radical access during pandemic times. Images of the printed zines appear below.

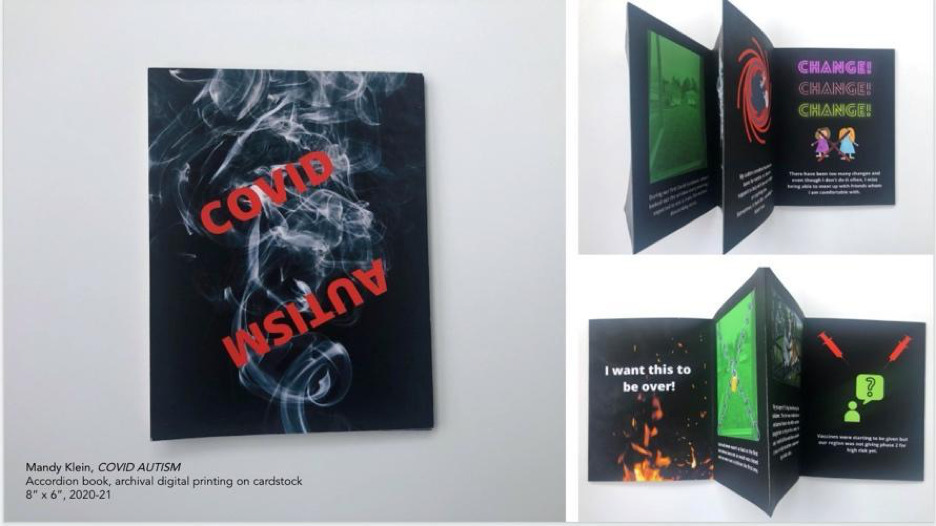

On the cover of Mandy Klein’s work (Fig. 14), the juxtaposition of “COVID” and “AUTISM” creates an unsettling effect of confusion and lack of control. The zine was printed not with flipping pages, but as a long accordion fold. This fold style not only displays the heavy impact of the content all at once, but imitates the “unwieldiness” of the autistic author trying to maintain calm routines during COVID. The “neon lights” appearance of the words helps to illustrate the author’s overwhelm: neon lights are a common source of overwhelm for many autistic people. Another visible page has a close-up photo of a sparking flame with text reading, “I want this to be over!” placed over top, suggesting that COVID has been ruinous for the author.

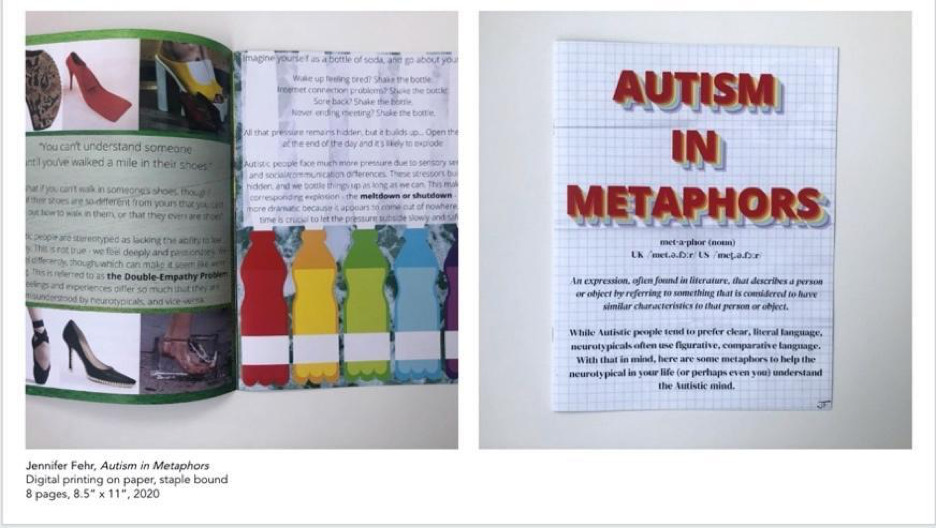

Jennifer Fehr’s Autism in Metaphors (Fig. 15) includes a dictionary definition of the word “metaphor” on its cover: “Metaphor: An expression, often found in literature, that describes a person or object by referring to something that is considered to have similar characteristics to that person or object.” The text continues on to introduce the zine’s concept: “While Autistic people tend to prefer clear, literal language, neurotypicals often use figurative, comparative language. With that in mind, here are some metaphors to help the neurotypical in your life (or perhaps even you) understand the autistic mind.” The graph paper background further represents this zine as educational material. On the first page, photos of shoes and the metaphorical phrase, “You can’t understand someone unless you’ve walked in their shoes” is used to introduce the concept of the “double-empathy problem.”35 This concept criticizes the idea that “autistic people lack empathy/understanding” and instead posits that autistic people and allistic people have such different ways of thinking that both groups often struggle to understand the other group’s feelings. The second page uses illustrated images of soda pop bottles as a metaphor to explain how meltdowns and shutdowns are like the result of shaking up a pop bottle: stressors build up pressure that must be released somewhere.

Finally, Venus Underhill’s Autistic Unmasking in the Time of Covid-19 (Fig. 16) uses horror-inspired images. On a black background cover, haunting magazine prints of doll-like, life-size clowns hover between various states of hauntingness, from humanlike and suffering to monstrous and mischievous. Peals of light obscure some of the figures, and further disturbing imagery—insects, a demon’s gnarled hand, and pointed horns—curl around the collage. Inside, a two-page spread features hand-drawn illustrations: a series of clown masks are unnervingly arranged around the doorway of a triangular building. Looking closer, readers can see the building is an optical illusion, with panels of wood crossing each other in impossible ways. To the right of the entrance stands a naked person in a top-hat, their torso cut open to reveal the panels behind them; at the top of the entrance hangs a cheery banner. Ignorant of its haunting surroundings, it reads, “Now smile.” The right side of the spread features a poem entitled, “I Only Feel Like Myself when I’m Alone.”

The process we document here—in disability justice activist Mia Mingus’ words—“leaves evidence behind” of how we have lived, loved, cared, and resisted during this time of crisis.36 This evidence also resists the creep of necropolitics, marking some bodies for the “living dead”37 and others for life exposed during the global health crisis and collectively imagines autistic futures as desirable,38 fundamental to life together and vital to us all.

Notes

- We use the term “neurodivergent” to refer to claimed identities that diverge from and disrupt what is considered neuro-normative. Neurodivergence refers to ways of being identified with labels such as autism, ADHD, brain injury and more. For more on terminology, see Nick Walker, NEUROQUEER HERESIES: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities (Fort Worth, TX: Autonomous Press LLC, 2021), 43–48; and Remi Yergeau, Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018). ↩

- For a more on the Re•Storying project, see the project website: www.restoryingautism.com. ↩

- Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018), 22. Also see the disability justice work of Sins Invalid, Alice Wong and The Disability Visibility Project, Lydia X. Z. Brown, Mia Mingus, and Syrus Marcus Ware, among others. ↩

- Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 92. Also see Lydia X. Z. Brown, “Bearing Witness, Demanding Freedom: Judge Rotenberg Center Living Archive,” Lydia X. Z. Brown, Laboring for Disability Justice & Liberation, July 15, 2021, https://autistichoya.net/judge-rotenberg-center; Margaret Gibson and Patricia Douglas, “Disturbing Behaviours: Ole Ivar Lovaas and the Queer History of Autism Science,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 4, no. 2 (2008): 1–28, https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v4i2.29579. ↩

- For more on autism tropes and the implication of mothers see Patricia Douglas, “‘As If You Had a Choice’: Autism Mothers and the Remaking of the Human,” Health, Culture and Society 5, no. 1 (2013): 167–181. ↩

- For more information on (re)storying/authoring autism see Patricia Douglas, Carla Rice, Katherine Runswick-Cole, Steacy Easton, Margaret Gibson, Julia Gruson-Wood, Esteé Klar, and Raya Shields, “Re-storying Autism: A Body Becoming Disability Studies in Education Approach,” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 no. 5 (2021): 605–622; Re•Storying Autism Writing Collective (Raya Shields, Steacy Easton, Julia Gruson-Wood, Margaret F. Gibson, Patty N. Douglas, and Carla M. Rice), “Storytelling Methods on the Move,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (online 20 April, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1563835; and Remi Yergeau, Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). ↩

- See, for example, Leah Harper, “From Ecocore to Hot Hot Hot: The Thriving Market for Sustainable Zines,” The Guardian, April 19, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2019/apr/26/from-ecocore-to-hot-hot-hot-the-thriving-market-for-sustainable-zines. ↩

- Bridget Liang, “Divided Communities and Absent Voices: The Search for Autistic BIPOC Blogs,” Studies in Social Justice 16, no. 2 (2022): 447–469. ↩

- For more about the zine-making workshop and resources created on online accessibility, see https://www.restoryingautism.com/collective. ↩

- See, for example, the Tangled Art + Disability website, https://tangledarts.org. ↩

- See Andrea LaMarre, Carla Rice, and Kayla Besse, “Relaxed Performance: Exploring Accessibility in the Canadian Theatre Landscape” (Online report prepared for British Council Canada, 2019), 1–86, https://bodiesintranslation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Relaxed-Performance-Full-Length-Report-Digital.pdf. ↩

- Jesse Stommel, Chirs Friend, and Sean Michael Morris, “Introduction: The Urgency of Critical Digital Pedagogy,” in Critical Digital Pedagogy, ed. Jesse Stommel, Chirs Friend, and Michael Morris (Washington, D.C: Hybrid Pedagogy Inc.), 4. ↩

- See www.restoryingautism.com/collective for the complete guide. ↩

- You can view this guide in its entirety here: www.restoryingautism.com/collective. ↩

- On access frictions see Aimi Hamraie and Kelly Fritsch, “Crip Technoscience Manifesto,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5, no. 1 (2019): 1–33. ↩

- For more on the concept of access doulas, a phenomenon that emerges from the work of Keith Gotkins and others in the disability justice and crip rave movement, see https://blackflash.ca/2021/09/14/access-magicians-in-cyberspace-care-as-a-festive-practice/. ↩

- On holding space as a critical ally, see L. Simpson, As We have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩

- For more on masking see below, and see Amy Pearson and Kieran Rose, “A Conceptual Analysis of Autistic Masking: Understanding the Narrative of Stigma and the Illusion of Choice,” Autism in Adulthood (March 2021): 52–60, http://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0043. ↩

- For an example of this kind of analysis, see Douglas et al., “Re-storying Autism.” ↩

- See, for example, the work of Hannah Thomspon and Jessica Watkin. ↩

- See K. Underwood, T. van Rhign, A. Balter, P. Douglas, B. Lawrence, and G. Parekh, “Covid-19, Disability and Childcare: A Disabled Children’s Childhood Approach,” Journal of Childhood Studies 46 no. 3 (2021): 16–29, https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs463202119970. ↩

- See footnote 4. ↩

- See footnote 18. ↩

- See footnotes 3 and 18. ↩

- See footnote 4. ↩

- See Tiffany Hammond on Facebook and Instagram, https://www.facebook.com/fidgetsandfries; https://www.instagram.com/fidgets.and.fries/. ↩

- See, for example, https://www.brandonsun.com/local/study-puts-indigenous-lens-on-autism-576196942.html and https://www.brandonu.ca/research-connection/article/decolonizing-stories-of-autism-in-education/. ↩

- See Katherine Runswick-Cole and Daniel Goodley, “The ‘Disability Commons’: Re-thinking Mothering Through Disability,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Disabled Children’s Childhood Studies, ed. Katherine Runswick-Cole, Tillie Curran, and Kirsty Liddiard (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave, 2018), 231–246. ↩

- Carla Rice, Andrea LaMarre, Nadine Changfoot, and Patricia Douglas, “Making Spaces: Multimedia Storytelling as Reflexive, Creative Praxis,” Qualitative Research in Psychology 17, no. 2 (2020): 222–239, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1442694. ↩

- Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

- Patricia Douglas, Carla Rice, and Areej Siddiqui, “Living Dis/artfully With and In Illness,” Journal of Medical Humanities, 41 (2020): 395–410, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-019-09606-5; Kelly Fritsch, “Cripping Neoliberal Futurity: Marking the Elsewhere and Elsewhen of Desiring Otherwise,” Feral Feminisms 5 (Spring 2016): 11–26; Nancy Loveless, How To Make Art At the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).; Alyson Patsavas, “Recovering a Cripepistemology of Pain: Leaky Bodies, Connective Tissue and Feeling Discourse,” Journal of Literary Cultural Disability Studies 8, no. 2 (2014): 203–218, http://dx.doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2014.16. ↩

- Mia Mingus, “Changing the Framework: Disability Justice,” February 12, 2011, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/02/12/changing-the-framework-disability-justice. ↩

- See Kelly Fritsch, “Cripping Neoliberal Futurity”; Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013). ↩

- “Autistic, Surviving and Thriving Under COVID-19,” Re•Storying Autism, www.restoryingautism.com/zines-1. ↩

- For more on the double empathy problem see Damian Milton, “On the Ontological Status of Autism: The ‘Double Empathy Problem,’” Disability & Society 27, no. 2 (2012): 883–887, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008. ↩

- Mingus, “Changing the Framework.” ↩

- See footnote 4. ↩

- See Kelly Fritsch, “Cripping Neoliberal Futurity”; Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip. ↩

![Gray theatre masks sit at the top inside a decorative circle, as if indicating a new chapter of an old, illustrated novel. White text below reads, “Unmasking is a conscious effort, it’s painful unpeeling the layers I’ve dawned [sic] in protection. I don’t want to preserve this diluted sense of self anymore, I’m not certain I could anyway. Forgoing my own comfort to make others more comfortable and avoid rejection, has made me hate myself. Resenting all the parts of me I can’t change. Covid has been isolating but masking has made me intimately familiar with isolation.”](https://csalateral.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/image-3.jpg)