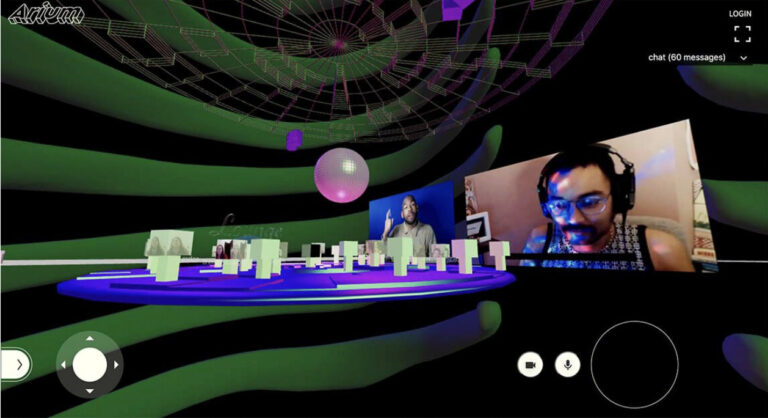

Remote Access is a disability nightlife event informed by disability history, technology, and artistry. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a collective of disabled artists and designers created an event to showcase how disabled people often participate in social life from our homes and beds. This contribution offers a living archive of the party and its evolution, as the planners created protocols for collective access through methodologies such as participatory audio description and live description of musical sound. We discuss how each new event offered opportunities for designing new practices based on disabled knowledge and expertise. As a result, the series of Remote Access nightlife parties became an ongoing opportunity to develop iterative accessibility protocols and community standards for remote/digital participation.

Keyword: crip

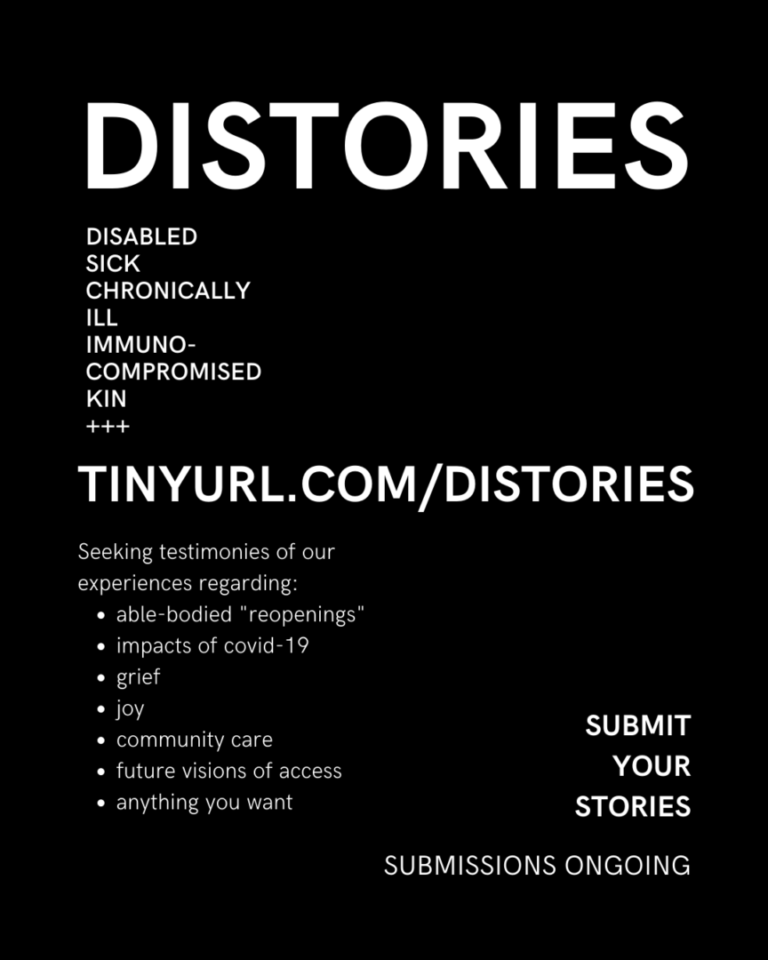

DISTORIES

DISTORIES is a small open-source and open-access Instagram zine project, gathering testimonies from disabled contributors. This project began in the context of the summer of 2021, as mask mandates and general precautions around COVID-19 were being relaxed. Each chapter of the zine is introduced by a question, framing stories and snapshots of experience as well as demands, affirmations, and dreams shared by contributors. The project was stewarded by geunsaeng ahn from September 2021 to July 2022.

Introduction: Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry

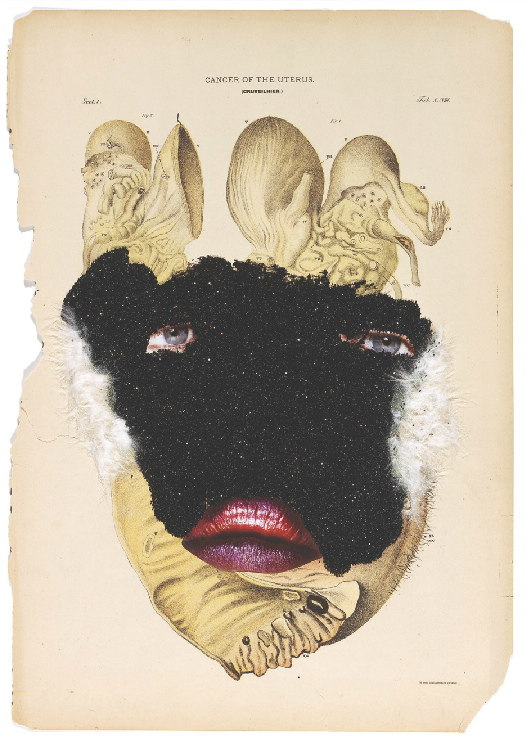

“Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry” takes up a thread from disability justice writer, educator, and organizer Mia Mingus to assemble an archive that “leaves evidence” and captures experience emergent from crip lives and life in the pandemic. The need to gather, hold space for, and preserve evidence—of our angers, our fears, our griefs, our joys, our pleasures, our communities, and our lives—has, for many of us, never felt more urgent. In this editorial introduction to the first installment of the special section of Lateral, “Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry,” we narrate project origins in response to pervasive and obfuscating crisis rhetorics, feelings of indignation, and a desire to gather and preserve evidence of crip life and crip knowledge from within the context of the pandemic. “Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry” offers a unique digital archive that brings together creative and scholarly reflections to document the experiences of disabled people during the COVID-19 pandemic. The collection includes a multimodal introductory roundtable; multimedia projects; digital renditions of sculptures, masks, fiber arts, and zines; critical interrogations of pandemic politics and policies; and theorizations of crip sociality. This editorial introduction is our brief overview and invitation for readers to travel through spacetimes, bear witness to, and be cared for by this tapestry, archive, collection.

Crip Pandemic Conversation: Textures, Tools, and Recipes

“Crip Pandemic Conversation: Textures, Tools, and Recipes,” brings together experts whose scholarship, curation, organizing and artistic work centers crip insights and creativity to reflect on the work that “Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry” undertakes. Margaret Fink, Aimi Hamraie, Mimi Khúc, and Sandie Yi each discuss how the pandemic impacted their work, and they join section co-editors Alyson Patsavas and Theodora Danylevich in discussing the tapestry’s content. Their conversation pulls out some of the most salient threads of the work: smallness, grief, care, community-building, tenderness, and pandemic coping tools. “Crip Pandemic Conversation: Textures, Tools, and Recipes” includes an unedited video recording of a Zoom roundtable session, a lightly edited text version of the conversation, and a glossary of terms that appear in the discussion, as a contextualizing access tool located at the bottom of the document. In choosing a preferred way of engaging with the content, we invite readers to consider, as the roundtable participants themselves do, how access (transcripts, zoom recordings, and captions) produces its own caring archive and knowledge-making practices.

Surviving and Thriving: Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa Dream Worlds in Animal Crossing New Horizons

As a queer, crip, genderfluid, and diasporic Pilipinx scholar-activist-educator, my ancestors, communities, and I live at the intersections of multiple sites of oppression and resistance. As someone who is sick, disabled, and neurodivergent, I experienced anxiety, depression, and chronic bodymind pain before the pandemic and even more during the pandemic. Nintendo Switch’s Animal Crossing New Horizons (ACNH) video game kept me afloat during uncertain times. ACNH opened up a whole new alternative universe for me to live in. I meditated more when escaping to my scenic and calming virtual island. I relaxed more when fishing, catching butterflies, and hearing the tranquil ocean waves crash within the game. Building my dream world within my ACNH virtual game contributed to me surviving and fostering deeper friendships with fellow sick, disabled, neurodivergent, queer, transgender, Black, Indigenous, and/or people of color (BIPOC) friends. ACNH became a safe way for us to socialize and it continues to be a source of joy for many of us. I highlight how my experiences with ACNH allowed me to cultivate queer, crip, and decolonial Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds where all beings including people, animals, land, water, and air thrive together.

Autistic, Surviving, and Thriving Under COVID-19: Imagining Inclusive Autistic Futures—A Zine Making Project

This article takes up Mia Mingus’ call to “leave evidence” of how we have lived, loved, cared, and resisted under ableist neoliberalism and necropolitics during COVID-19 . We include images of artistic work from activist zines created online during the COVID-19 pandemic and led by the Re•Storying Autism Collective. The zines evidence lived experiences of crisis and heightening systemic and intersectional injustices, as well as resistance through activist art, crip community, crip knowledges, digital research creation, and the forging of collective hope for radically inclusive autistic futures—what zine maker Emily Gillespie calls “The neurodivergent, Mad, accessible, Basic Income Revolution.” We frame the images of artistic work with a coauthored description of the Collective’s dream to create neurodivergent art, do creative research, and work for disability justice under COVID-19. The zine project was a gesture of radical hope during crisis and a dream for future possibilities infused with crip knowledges that have always been here. We contend that activist digital artmaking is a powerful way to archive, theorize, feel, resist, co-produce, and crip knowledge, and a way to dream collectively that emerged through the crisis of COVID-19. This is a new, collective, affective, and aesthetic form of evidence and call for “forgetting” ableist capitalist colonialism and Enlightenment modes of subjectivity and knowledge production that target different bodies to exploit, debilitate, and/or eliminate, and to objectify and flatten what it means to be and become human and to thrive together.

On Navigating Paranoia, Repair, and Ambivalence as Crip Pandemic Affects, Or, I’m So Paranoid, I Think Your COVID Test Is About Me

How do my “hermeneutics of suspicion” color this current crisis? In this auto-theoretical essay, I reflect upon the blend of judgment, suspicion, and paranoia that have settled into my body-mind this past year, and how these feelings shape my engagement with people, institutions, and systems. I have been taught that “judgment” is an essential aspect of immigrant and crip safety. Recently, it has become my (crip)epistemology, and I cannot decide whether this is for better or worse. On the one hand, suspicion is productive. It has kept me and my loved ones alive in a time of deliberate death. On the other, it frustrates, disrupting my capacity for connection. I check my temperature constantly, I hear the guilt in my voice when my family in India tell me they have not left the apartment in months, I spend precious time with friends calculating their risk relative to mine, I go to protests but am afraid of the consequences of my solidarity. Drawing on Eve Sedgwick’s essay on paranoid reading practices, Patricia Stuelke’s Ruse of Repair, Sianne Ngai’s work on ugly feelings, Nikolas Rose’s analyses of somatic ethics, and Mel Chen’s theory of racialized toxins, I explore the modalities that paranoia has both enabled and disabled for me. I examine my ambivalent relationship with repair—some reparative practices like mutual aid sustain queer/crip/immigrant community while others like cure constrict our lives. This piece aims to tease out the tensions latent in crip worldmaking between suspicion and generosity, public health and communal care, and paranoia and repair.

The Queer Aut of Failure: Cripistemic Openings for Postgraduate Life

I, a Mad, autistic, multiply-disabled person, began my PhD in Cultural Studies in September of 2020. I started to make my home in graduate school during the COVID-19 pandemic, fully online, and I’ve excelled, calling into question normative assumptions of in-person socialization, education, and collaboration as superior to their virtual counterparts. In this article, I reflect on the cripistemic pedagogies of failure that facilitated a neuroqueered and transMaddened transition to Zoom-based graduate life. I will also consider email, text messages, and video calls as equalizing mediums in which both formal and fugitive spaces can open for queercrip collaboration across borders, timezones, and access needs. Lastly, I will tell the stories of technological “failures” that I have experienced—miscommunications, failing internet, time delays—as generative possibilities rather than indictments of a non-normative learning. Necessarily imperfect and rife with humorous, intriguing, and profoundly human failures, as well as surprising and generative openings, pandemic education has ushered in new queercrip, transMad, ways of knowing and teaching that have uniquely benefitted me. Far from a circumscribed or lacking educational landscape, I argue, post-COVID academia is filled with pedagogical and epistemological openings, holes through which new disabled and Mad scholars, myself included, can make ourselves a beautifully imperfect home space. I invite you inside.

Roundtable: Crip Student Solidarity in the COVID-19 Pandemic

This roundtable shares the first-hand experiences of five crip, disabled, Mad, and/or neurodivergent doctoral students navigating academia in so-called Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. While we discuss and theorize our experiences of ableism, structural oppression, and inaccessibility in the academy, we also highlight the world-building experiences of solidarity that have emerged for us in crip community, and in particular among fellow crip graduate students. We consider the ways that crip students open up potential for new ways of learning and being by challenging dominant norms of academic productivity, and we also consider what is lost when these students are pushed out of academic spaces. By engaging in “collective refusal” of the conditions that harm disabled and otherwise marginalized students, new possibilities emerge for connection, community, and radical change. The virtual conversation transcribed here took place over Discord, email, and Google Docs in autumn of 2021 and early winter 2022. This piece embraces multi-tonality, that is, a range of different voices and ways of writing, speaking, and communicating. It is a conversational piece that intentionally blends varied approaches to knowledge-sharing: polemic, citationally-grounded, and personal anecdotes drawn from our diverse lived experiences. There are a number of different themes woven throughout the text, including anecdotes and personal history, solidarity, ableism in the academy, pessimism/failure, community/interdependence/intimacy, and utopia/futurity/demands for the future. While not intended to provide policy guidance or step-by-step instructions for changing academic culture, we also begin to sketch out some of our dreams for an alternative future for disabled scholars. We discuss imagined futures and possibilities, and ask, is a truly crip and/or accessible academic institution possible?

August 2020

Unemployed at the time, not visibly disabled, but having become quite unwell in the middle of a pandemic, this poem illustrates my anxious and exhausting insomnia against the caretaking labor for my youngest child. I worked to minimize the projections of stress and anxiety onto her, laboring for stillness and comfort. As Luce Irigaray states in An Ethics of Sexual Difference (1993), “Music comes before meaning. A sort of preliminary to meaning, coming after warmth, moisture, softness, kinesthesia” (168).

Crip Collectivity Beyond Neoliberalism in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower

The importance of Octavia Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower continues to crystalize, as Butler’s prescient imagining of urban California torn apart by neoliberal divestment comes to fruition. Following in the space opened up by Black feminist scholarship on Butler, the present essay examines her relevance beyond literary and cultural studies. I argue that Parable is a Black feminist crip theorization of political economy that diagnoses the disabling conditions of precarity under neoliberalism and also prescribes collectivity for crip and mad survival. Neoliberalism describes a global stage of advanced capitalism wherein governments are both incentivized and disciplined into enforcing economic policies that include privatization, deregulation, and market liberalization. As Jodi Melamed defines it, neoliberalism requires a certain kind of political governance, that puts the interests of business over the well-being of people (2011). Neoliberal governance engenders what I call “disabling contradictions,” yet the blame for conditions of precarity is deflected onto bodyminds themselves. In Parable of the Sower, Butler theorizes these disabling contradictions of neoliberal governance under advanced capitalism, drawing into focus the political economic systems that cause suffering. Parable also depicts strategies for crip and mad survival that are made possible through the conscious creation of community and networks of solidarity that counter the neoliberal state’s devaluation of bodyminds. Gathering to read and discuss the novel, rather than a distraction from the crises, furthers the emergence of crip and mad collectivities. As such, it is an urgent and timely practice for building futures for crip and mad people.

Crip Twitter and Utopic Feeling: How Disabled Twitter Users Reorganize Public Affects

Conceptually, online activism remains a divisive concept: detractors decry it as low-commitment “slacktivism,” and proponents argue that the Internet is a powerful platform for organizing. Particularly for disabled persons, the Internet provides new avenues for engagement and organizing work by allowing disabled persons in disparate places to connect with each other. While the intersection of disability activism and online activism remains underexplored, existing literature remains anchored to the notion that disabled online activism’s greatest impact is in organizing physical protests and actions. This paper scrutinizes the actual work and impact of three disabled Twitter activists, and wages an argument based on how Twitter activists make other users feel. Particularly, this paper synthesizes affect theory with Althusser’s notion of “interpellation” and revises Michael Warner’s theory of “publics” to argue that such disabled Twitter activists and their followers mutually generate networks distinguished by shared feelings (affective networks, as this paper terms them), and that these networks are constantly being renegotiated and transforming the feelings of their members. The paper makes four key interventions: first, it writes against Michael Warner’s initial reluctance to include the Internet in his theory of publics, by arguing that Twitter followings model Warner’s publics. Second, it performs close readings to describe both how Twitter users’ writings generate affective networks and what activist impact these affective networks have. Third, it identifies and describes radical optimism and the utopic work of “demanding” as constituents of Twitter users’ affective networks. Finally, this paper examines and describes how affective networks shift with each tweet, and how such writings transform the feelings that constitute those affective networks. Arguing in part from my own subjectivity as a disabled Twitter user, I contend that Twitter enables disabled users to organize their feelings according to the feelings they want to have, and the feelings they think they ought to have.

Toward a Crip-of-Color Critique: Thinking with Minich’s “Enabling Whom?”

Response to Julie Avril Minich, “Enabling Whom? Critical Disability Studies Now,” published in Lateral 5.1. Kim elaborates upon a crip-of-color critique, which has possibilities to both criticize structures that inherently devalue humans and to take action to work toward justice. Kim’s final call is to identify and act against the inequalities and harm of academic labor, urging readers to take seriously a “politics of refusal” that might help academics of color survive through alternative collectivities.