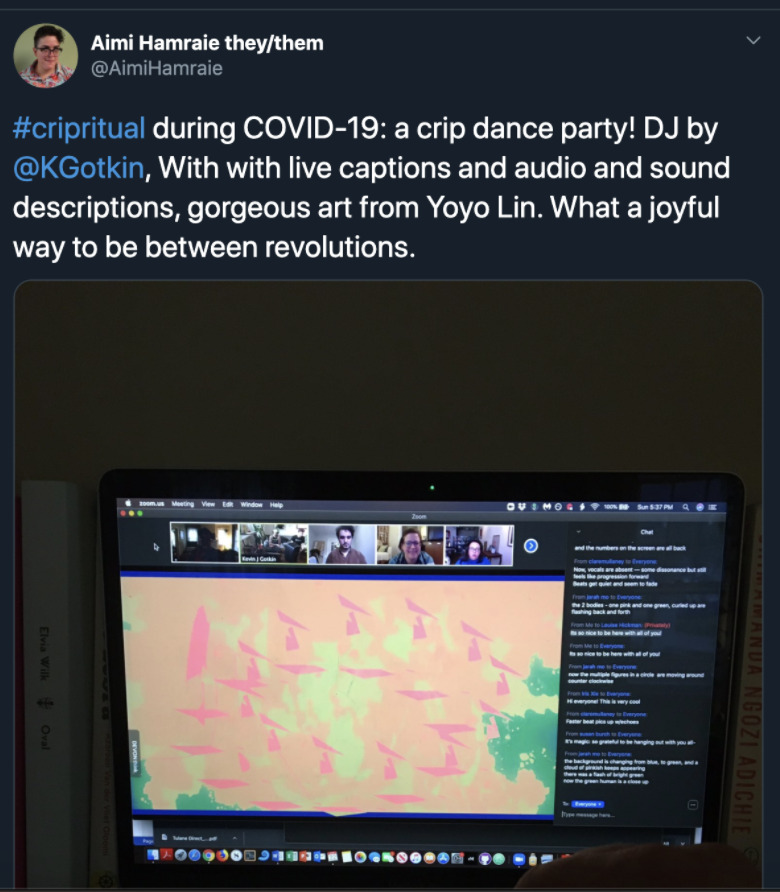

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in the United States during March 2020, there was so much fear and confusion. But as disabled people, we knew that we had to carve out space to be together, even at a distance.1 We already knew how to do this. We had done it many times. So we planned a party. It started like this . . .

March 12, 2020: a text exchange

Aimi: Hey Kevin! You’ve been on my mind.

How are you doing with all of this COVID stuff?

I’m also wondering if you know of anyone DJing crip parties online for folks to be together in this time (and whether this is something you think Critical Design Lab might want to organize)

Kevin: Thank you for checking in!

I would LOVE to organize a crip online party! Let’s totally do this!

Aimi: Let’s figure out a party time! I have Zoom pro through work and we can gather other resources together, too! <3

Kevin: I think i know how to send audio from my DJ controller to Zoom

Aimi: Awesome! Maybe we can pick a date and then find a few people to participate so you don’t have to DJ the whole timeMarch 14, 2020

Kevin: Are you around today? I could start an email thread with some folks who would be wonderful digital access doulas

Aimi: Yeah, definitely. I can send a Zoom link.

Are you making the Google doc or should I?

Kevin: I’ll start it up

Aimi: I made a page on the [Critical Design Lab] website

Kevin: Here is a participation guide: Remote Access: a crip nightlife gathering

I’m reaching out to a rad CART provider

Aimi: Maybe we can include some #CripRituals?

Kevin: woof love that

Now I’m thinking about how we could connect with mutual aid/fundraising efforts? Maybe in the participation guide?

Aimi: Yeah, that sounds great.

Kevin: okay so the audio is muuuuuch better when we use another streaming platform. Sounded great on twitter and instagram. But downside on all non-Zoom platforms is that it doesn’t really feel like a gathering.

Aimi: great, how does captioning work on insta?

Kevin: if we’re describing the DJ set only and people aren’t coming on to say hi with their audio, i think we just go with the sound describers who will use the chat to put lyrics, aesthetics, etc. and an audio describer can come into the story periodically to describe things.

Aimi: Keep me posted! I gotta plan my outfit.

Kevin: Same! I need to stage the whole DJ booth and everything!

“Remote Access: a crip nightlife event” is a disability nightlife party informed by Kevin Gotkin’s research on histories of crip nightlife, the Critical Design Lab’s disability culture protocols, and the expertise of disabled artists, such as moira williams, Yo-Yo Lin, Ezra Benus, and others. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a collective of disabled artists and designers (including Kevin Gotkin, Louise Hickman, and Aimi Hamraie) created an event to showcase how disabled people often participate in social life from our homes and beds. This event drew on knowledge and practices we already had: how to hire interpreters and CART providers, how to stream video, and how to find creative ways to meet online. We combined elements of collective access2 through methodologies such as participatory audio description3 and live description of musical sound. Gotkin conceptualized “Access Doulas” as roles that would usher participants through the party’s live DJ sets and disability arts showcases. As the broader collective (some of whose names appear in Figure 1) offered more parties, we also refined our protocols to build expansive methods of care and camaraderie. The events took on many iterations depending on the context, including Sunday afternoon gatherings, conference events, celebrations, digital worlds, and artist residencies. Each time, we incorporated new technological modes and tools. As a result, the series of Remote Access nightlife parties became an ongoing opportunity to develop iterative accessibility protocols and community standards for remote/digital participation. Whether as party organizers or attendees, we left each party with feelings of joy, gratitude, connection, and desire for reconnection. We also found ourselves with more questions about how to further extend this critical aesthetic and cultural practice through a commitment to disability justice and disability culture.

March 22, 2020: post-party text exchange

Kevin: fully crying

THE BEAUTY

Like wow

Aimi:The best! Thank you soooo much!

Such love and community

We had up to 90 people at one pointMarch 28, 2020:

Kevin: hi! Babes are still living from the party last weekend. How would you feel about planning another one? And maybe developing a program of people to share work? I know people who are interested.

Aimi: yes yes yes!!!

I live for this

In this submission to “Crip Pandemic Life,” we offer a layered archive of the unfolding exchanges, ideas, events, conversations, and protocols that shaped the Remote Access nightlife party. There is a large concentration of disabled artists and cultural producers represented, as both organizers and participants have grown out of networks of collaborators. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that there are limitations to the archive that we present here.4 In future work on the project, including the Remote Access Archive, we hope to gather impressions, documents, and other data from a broader range of organizers and participants.

Taking an approach that foregrounds available primary sources, we aim to present the reader with an immersive experience that includes text and images. Sometimes, an image or form of documentation will appear first (accompanied by an image description, per our protocols) before we explain it. As a reader, you are invited to engage linearly or move to different sections as your interests guide you.

We begin with a brief description of how the term “remote access” became meaningful for us and shaped the party as a form of ritual. We move into describing the evolution of different spaces in which we have held the party. Then, we focus in-depth on the methods of remote access, including the accessibility protocols developed for various iterations of the party. Finally, we discuss Remote Access as a reflection and practice of disability culture.

The Ritual of Remote Access

“Remote access” is a term that describes ways that disabled people create accessibility for ourselves and each other. We do this as part of a broad, collaborative disability culture, a culture that often takes shape at a distance. Remote access describes myriad media and methods of engagement. For example, it encompasses web streaming, live chats, sending letters or text messages, communicating through newsletters, and many other media, digital and analog. (The Critical Design Lab is exploring the history of this concept through the Remote Access archive). Aimi Hamraie resonated with this term during the Occupy movement while doing disability justice organizing with Occupy Atlanta. One facet of this organizing was creating accessible livestreams of General Assemblies. Later, Hamraie brought these methods to organizing with the Nashville Disability Justice Collective. But all of us have engaged in forms of remote access, increasingly so in this digital age, and often in ways that are complicated and full of friction. We have asked for remote access to school, work, conferences, and art events, and have often been told that this form of accessibility is too expensive or complicated. Even before the pandemic, we stitched together our own forms of remote access in order to be together across long distances, to feel less alone. We know that remote participation is possible–technologically and financially–and that it is also imperfect, fraught, dependent on access to money and infrastructures that are not widely distributed. We have our limits in digital spaces and online time. Many of us still face barriers to usability in these spaces. Nevertheless, remote access is an essential tool for connection and collaboration. We felt the significance of remote access when we also encountered the pain of watching the world suddenly adopt some of these practices in 2020–2021 when non-disabled people needed them, only to take them away when vaccines became available in the United States.

Remote access is part of broader “crip technoscience” practices of remote connection (Hamraie 2017; Williamson 2012), through which disabled people share knowledge about hacking and tinkering across long distances in order to generate community, often through mutual aid.5 Specifically, by using a party as the basis of crip, Deaf, blind, chronically ill, and neurodivergent design iteration, we found generative opportunities to show the protocols that already exist in disability culture, as well as to create new ones that were inconceivable before the pandemic. We sought to document the protocols and practices of remote access in order to counteract the current refusal of distanced options (and the attendant forgetting that such options were widely used in the early pandemic years). In documenting remote access in this way, we hope to clarify its role in the tapestry of crip pandemic survival and thriving.

Remote access is a crip ritual, repeated and re-iterated within disability culture. When we create opportunities for remote participation, play, and community, we not only create more inclusive spaces, but also often end up with unexpected practices or material forms. Since March 2020, each Remote Access party has been the site of emergent accessibility practices, which we will describe in more detail in the next section. Each party begins with a participation guide, the first of which was created by Gotkin and disabled scholar and artist Louise Hickman, with some help from Hamraie, in 2020.6 The participation guide provides a Zoom link, timetable of activities and presentations, accessibility information, links to relevant files (such as the participation cards discussed later), and other tools for taking part in the party.

Each time we host and produce one of these parties, we immediately find ourselves repeating rituals of access-making, rituals of disabled cultural production, and rituals of community expansion. In a July 2020 party called “Remote Access: Witches ‘N’ Glitches,” held at the Allied Media Conference (AMC), we created an explicit ritual container for disability culture. For many conference attendees, the party was their first exposure to disability culture. This was despite the fact that one of several early sites for the articulation of disability justice concepts took place through Creating Collective Access, an intervention into the AMC space in 2010.7 Staging Remote Access within the AMC’s first all-digital conference allowed us to hold a pocket of disability culture outside of the conference’s normative time and space. We marked this space through an opening invocation by Hamraie, which has now become a feature of most of the parties:

We welcome you to the crip ritual of Remote Access, a way to celebrate and be together that emerges from crip culture. We’ll start by creating a container for our party by imagining our spaces glowing with pink and purple light. Imagine your space as a bright dot on a map of the night sky. When we zoom out, your bright dot appears scattered across a landscape of other dots, with lines connecting them until multiple concentric circles of purple and pink light form. They shimmer. And within that shimmering, we charge up our circles with elements of crip power.

We call in the power of CRIP ACCESS: crip as refusing normalcy. Access as the flow of radical love and hospitality. Crip access as the element of facilitating belonging together for all of us and refusing to leave any of us behind. Crip access as flexible, ingenious, creative, and world-changing.

We call in the power of CRIP RAGE. Crip rage as non-compliance, the fire of crip protest, the smash of sledgehammer against sidewalk, of body against inaccessible building.

We call in the power of CRIP HUMOR. Crip humor is irreverent, taboo, biting, political. Crip humor as turning the gaze back onto Ableds. Crip humor as a cornerstone of crip ritual.

We call in the power of CRIP SLOWNESS. Crip slowness as valuable methodology and technology. Crip slowness as focusing away from ableist futures toward the pleasures and value of the present. Crip slowness as a way to move and a way to know.

We call in the power of CRIP PLEASURE. Crip pleasure as the joys emerging only from crip culture. Access intimacies, shared skills and stories, accessible potlucks, mutual aid networks, extended kinships, and access as love.

With this invocation, we asked participants to imagine reaching out to others on the Zoom screen, connecting across time and space as disabled people often have in our uses of remote access. We also invited play and stimming, alongside dancing.

In these and other rituals, we found that access-making is not merely translational; it is also playful. For example, to document and capture the energy of the Witches ‘N’ Glitches party, artist moira williams created collaged drawings of presenters (Figure 5), while other artists, such as Maya Suess, drew their own representation of moira’s performance of a spell (Figure 6). These visual representations (and their descriptions) captured the energetic connections between participants and disabled artists showing their work. Transmitted across digital space, these analog forms of representation were emergent within the party space itself. That is, rather than being pre-planned forms of access, participants reached for them as improvisational tools that may or may not appear in future protocols.

Spaces of Remote Access

Over the last two years, Remote Access has been hosted in a number of digital spaces. In this section, we review how the evolution of the party reflected the constraints and opportunities that these spaces provided for developing accessibility protocols. In doing so, we hope to convey the open-ended, experimental sensibility of access-making that characterizes the project.

Initially, Kevin Gotkin (also known as DJ Who Girl) had practiced online DJing through livestreams on Twitter and Instagram. As they began imagining the Remote Access party, however, these platforms were inadequate for providing accessibility, let alone providing a feeling of being in a party space with other people. The party planners chose Zoom as an alternative platform because it allowed the layering of sound and images with their descriptions, participant chatting, and ways of seeing and being seen on the screen. While making this choice, we were aware of the inadequacies of this platform compared to alternatives such as Google Meet, which some participants and access doulas (particularly Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing people) preferred for access to meeting settings. Both platforms underwent many updates, with new features added periodically as the pandemic unfolded. They each had varying degrees of reliability in terms of video speed and audio quality. Each of these platforms also had its own approach to showing captioning and allowing ASL interpreters to be “pinned” on the screen. New accessibility methods opened up within Zoom when organizers, who included both hearing and Deaf/HoH people, experimented with appropriating some of the new features for other (accessible) ends. For example, Gotkin and Hickman found that the new language translation channel (for providing audio translations of Spanish or French, for example) could be used for live audio descriptions, which participants could play over the music. Kevin also figured out how to connect his DJ tools to Zoom and override the platform’s tendency to even out bass notes or background noise.

As the party became more popular, we were asked to put on events for conferences, such as the Society for Disability Studies meeting (April 5, 2020 and April 20, 2021). At the in-person version of this conference, the “SDS dance” is an acclaimed site for disability nightlife, a fabled disability cultural space that often serves as the highlight of the academic disability studies year. Accounts of the SDS dance often offer it up as a material example of how disability culture, identity, and community take shape for participants, both those who identify as disabled and those who identify as non-disabled.8 In taking the SDS conference online due to the pandemic, the conference organizers worked with Remote Access to reproduce this experience in digital space. Participants and access doulas (such as Margaret Louise Fink, shown in Figure 7) approached the event as a festive occasion for connecting across long distances. The SDS Dance: Remote Access edition built on the in-person event’s celebration of disability choreography, commitment to fashion as expression, and celebratory music by bringing these into a virtual space where additional accessibility practices (including image and sound description, as well as the option to participate from home or bed) were available to participants. In these ways, Remote Access extended the forms of disability design experimentation that were already part of the SDS dance into the emergent remote disability spaces of the pandemic.9

While Zoom remained a preferred platform for the Remote Access party, new technologies and the ingenuity of disabled artists built upon this platform to afford additional experiences of sociality. Artist Yo-Yo Lin, working with Gotkin, designed the GlitchRealm using the three-dimensional digital platforum Arium. Partygoers could participate either through Arium or through Zoom, and the Zoom screen (with ASL interpreter and live captioning) appeared within Arium on the “dance floor” (Figure 8). Partygoers in the GlitchRealm navigated the space with live avatars. They were greeted by access doulas as they moved through designated areas within the 3D space, such as the dance floor, karaoke room, and quiet space. These areas were all labeled and participants could reach them using keyboard keys. A unique feature of Arium that reproduced some elements of a party experience was that the sound volume would increase when an avatar moved closer in proximity to one of these spaces or to another avatar, giving the experience of being in a live space (Figure 9). Those of us preferring more intimate spaces could visit the karaoke room (facilitated by moira) (Figure 10) or the quiet/Spoonie space, where the music was not audible. Also inside the GlitchRealm were works of art by disabled artists, such as Finnegan Shannon’s blue benches asking participants to sit and rest (Figure 10).

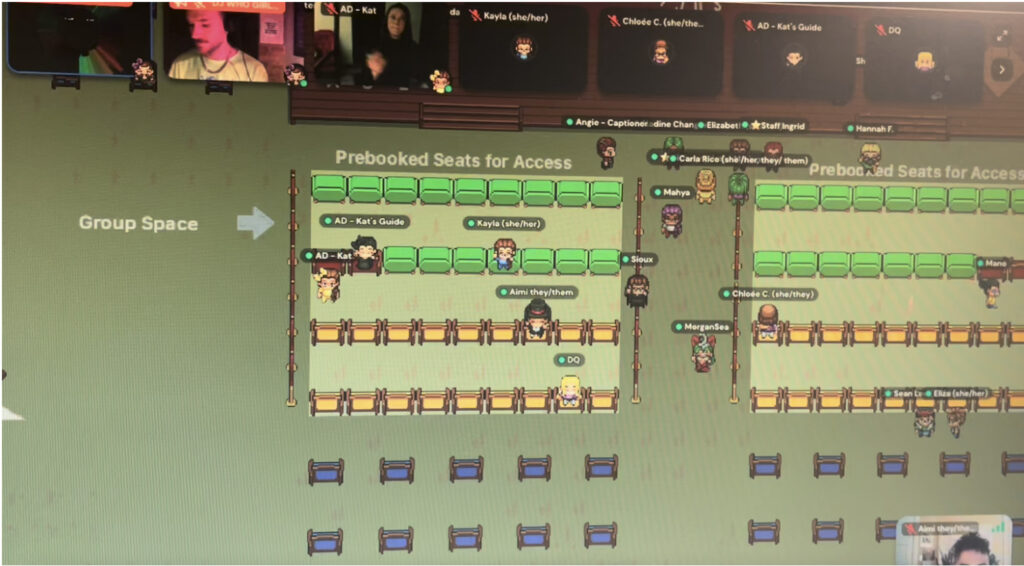

Another party was held in a virtual conference platform called Gathertown, which is a video game-like space (Figure 11). Unlike the GlitchRealm, Gathertown is a two-dimensional digital space. The avatars are self-fashioned using a menu of fashion and appearance choices. They navigate through the space using arrow keys and keyboard shortcuts allow them to appear to be dancing. In this version of the party, which celebrated the Practicing the Social Conference at the University of Guelph (held online from January 20–22, 2022), the DJ and access providers appeared at the top of the screen, but the usual Zoom functions were not available. Access doulas provided image descriptions of the look and feel of Gathertown and helped participants navigate the space.

On July 11, 2021 another iteration of Remote Access took place within a hybrid container, with both remote virtual and in-person options for participation. The Remote Access Disability Cabaret and Dance Party (or “barge party”) was held on an accessible barge in New York City. Participants and organizers gathered at The Waterfront Museum in Brooklyn, New York to celebrate extended comment deadlines for New York City’s cross-disabled communities concerning the local Comprehensive Waterfront Plan. Specifically, partygoers were celebrating the addition of a nearby accessible public bathroom, along with an accessible barge (which served as a party boat) (Figure 12). This party in early July 2021 coincided with New York City’s reopenings after periods of pandemic lockdown. Designing a hybrid party was more complex than simply following the protocols for a remote party in physical space, however. Even more complicated was a hybrid party centering cross-disability access and culture. Organizers were concerned about addressing partygoers’ anxieties about being in-person again. The task was to cocreate abundant and flexible access that could afford participants a cohesive social experience.

The barge party took water as its theme. This theme built on the celebration of accessibility on New York City’s waterfront by also imagining “water intimacy,” an extension of Mia Mingus’s concept of “access intimacy.”10 moira williams had developed ongoing water intimacies as a focus of their work through the Works on Water exhibition and arts organization Culture Push’s Tending the Edge. These existing collaborations around the theme of water enabled the party’s celebration of accessible waterways to tap into a network of interested celebrants. The party was rich with people willing to collectively support access, and to experiment with different options for access and socializing across time, space and technology.

The Waterfront Barge Museum’s expansive size, multiple large open doors, secluded inlet with a large dock and bench-filled park were ideal in that the space architecturally supported both COVID-19 and accessibility protocols. In total, there were four performances (two in-person and two remote), as well as one video screening. For example, presenter BI3ssing Oshun Ra joined via Zoom (Figure 14). Each performance was projected into Zoom and was displayed on a large screen in the barge space. Access doulas helped both remote and in-person participants navigate the party. In- person access doulas identified themselves by wearing orange (“access”) sashes covered in black and white checked pins with colorful feathers (Figure 13), whereas online access doulas used a black and white access doula virtual background (right lower corner in Figure 15).

The in-person experience offered multiple access points. Eight access points spread across the barge and dock. Several were small cozy areas with an access doula in attendance. Another was a larger, texture-filled, and cozy, chill crip fringe stim joy space offering pillows and swimming pool inflatables for comfort and multiple ways for sitting, stretching out, or curling up. Two access doulas also wandered and mingled throughout the party. One access doula facilitated engagement between in-person and remote partygoers via a large screen, a camera, and laptop. Each provided audio description, basic barge information and Participation Guides. Participation Guides included accessible directions, an onboard access points map, non-alcoholic drink recipes, and ideas for stim fringe joy. The guides also helped participants understand how to interact between platforms, connect with online attendees via Zoom on their phone, and sign up for access doula duties.

Remote partygoers experienced forms of access available in previous remote parties, as well as new experiences of access, including interacting across platforms. These experiences included direct conversations with DJ WhoGirl (Kevin Gotkin), moira williams, and Clarinda Mac Low, the access doula who coordinated engagement across platforms. Access doulas greeted and chatted with participants on Zoom and shared information about the barge and the surrounding neighborhood. At one point, sound qualities were disrupted between the remote and in-person party during a video screening. Because of the parties direct interactions between online and in-person partygoers along with the access and communication support provided by the online access doulas, moira and Clarinda acknowledged and corrected the sound glitch immediately. The video resumed with moira reading the transcript aloud for both in-person and online partygoers, relieving any kind of tension between formats and partygoers experiences. The immediate and momentary stop to negotiate access for and with the online partygoers ultimately added to everybody’s experience as being part of the party and supported (see “Chat excerpt”). Maya Shah and Alberto Jiménez served as roaming live-streamers wandering throughout the party and performances with an iPad describing what was going on and activated connections between remote and in-person partygoers. Shah’s and Jiménez’s descriptions addressed the weather, sounds, and smells along the waterfront for remote partygoers. In-person partygoers used their own devices to contribute to these descriptions as well.

Whether completely remote or hybrid, Remote Access participants experienced accessibility as a commitment, an attitude, a flexible and adaptable set of practices, and as a way of designating spaces for disability culture outside of normative space and time. As a result, organizers found that opportunities emerged for cross-disability solidarity, emergent practices, and abundance. In the next section, we explore the methods and protocols of Remote Access in greater depth.

The Methods of Remote Access

The Remote Access party is a media production that has developed through many iterations and accordingly represents an evolving array of accessibility practices. Participants and access doulas enact some of these practices within the party itself, while organizers prepare some of them behind the scenes. Each party begins with a participation guide, which outlines the accessibility information, policies, and procedures. The guide also calls for volunteer “access doulas” who will help participants navigate the space. These participation guides developed progressively, with additional protocols and procedures added before new parties. Remote Access protocols integrate standard and predictable forms of access with emergent practices. From the beginning, every Remote Access party has included American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation, live captioning, and image descriptions. In addition to these better-known elements of access, the parties have also developed a number of other methods of access-making. Below, we outline the central roles and elements that we found most important in defining our party protocol.

Access Doulas

Although the parties emerged from Gotkin’s DJ practice and Critical Design Lab protocols, party organization quickly became a collective endeavor of “Access Doulas,” disabled and non-disabled people who took on the work of facilitating access in real time. The concept of doula-ing names access as a type of care that needs attending-to, a commitment to access-making through a temporal duration, and a type of labor that can be practiced and cultivated. Kevin thought of the term “access doula” in early party-planning as an extension of other doula practices, including birth, death, and HIV doulas. Within the party, access doulas take on roles such as helping with audio and sound description, guiding participants in the space, answering questions, and offering technical and emotional support.

The access doula model is based on mutual aid principles related to “collective access.” 11 For example, while organizers may aspire to encourage participatory forms of access-making, we also recognize that there are differences in the quality of access afforded by professionalized disability access providers (such as CART and ASL providers, and between Deaf and non-Deaf ASL interpreters) as compared to participants who may want to transcribe text in the chat or who may want to contribute ASL but are not fluent signers. There are also differences between practices (including CART and ASL) that have established norms of practice and those that are more emergent, including artistic approaches to sound description or participatory image description. In addition, the parties serve as a space for aestheticizing various forms of access (such as in Figures 5 and 6).

Thus, in attending to access as a form of labor, we wanted to define the concepts of “access” and “labor” as broadly as possible. At the same time, we faced a paradox. As a priority, we wanted to ensure fair compensation for this labor. This priority came up against the party’s commitment to do-it-yourself (DIY) forms of access, which we had originally adopted as a gesture of disability resourcefulness when we had limited access to money or technical resources. In terms of DIY access, we wanted access labor within the party space to be a seedbed for collective access, something that participants could take with them into other spaces or future parties. In addition to all of these commitments to more equitable access labor, we sought to redefine the labor of participation, particularly in a very Zoom-saturated time, by incorporating neurodivergent protocols for signaling capacity for participation (such as through participation cards that moira developed, explained further below).

As organizers, we have taken the opportunity to understand access labor as a seedbed for organizing toward more skilled access doula-ing practices. For example, when participants sign up for access doula roles, they are also invited to continue to participate as party organizers. As a result, Remote Access has developed a party structure that retains the institutional and technical memory of emergent access practices, but is ultimately non-hierarchical and horizontal in terms of distributions of power. Organizers make arrangements behind the scenes, while participants both receive and produce expansive disability culture-informed forms of access. Together, they participate in collective and embodied responses to music, art, and sociality. As organizers, we have watched transformative processes emerge as party attendees co-witness and co-participate in processes that we understand as crip technoscience, participatory cultural abundance, crip celebratory resistance, and public political agency. In the coming sections, we focus on two emergent practices–sound description and participation cards—that are still developing within the Remote Access space.

Sound Description

Because Remote Access is a dance party with live DJ sets, sound description has emerged as an important method for conveying music in multiple accessible formats. Descriptions of sound include lyrics, the sonic qualities of singing, beat and rhythm, and mood. During the parties, sound descriptions are often offered in the chat, as well as in a separate document. Creating sound descriptions requires pre-planning and coordination amongst artists, access doulas, and access providers. For example, Kevin Gotkin (DJ WhoGirl) produces descriptions along with their DJ set, in cocreation with other access doulas, before the party. These descriptions are shared ahead of time with the ASL interpreter and CART provider to help them prepare. During the party, the sound descriptions are entered into the Zoom chat, in addition to being made available via Google Doc to participants. The table below shows an example:

| DJ SET #1 | ||||

| CLOCK TIME (ET) | FILE TIME | TRACK | LYRICS | DESCRIPTION |

| 8:00 | 00:00 | “4T Recordings” by Four Tet x “A Spell for the Present Moment” by Beverly Glenn Copeland | Open the way inside youThe universe is your only breathSurrender to the present momentWhat’s coming now is all that’s leftMany rivers flow through usMany creatures become usMany storms change the journeyThe dirt keeps calling us home Open the way inside youThe universe is your only breathSurrender to the present momentWhat’s coming now is all that’s leftSeed the soil within youYou drumbeatYou shimmering leafListen for the sound of sunlightLive a life that’s worth your grief Open the way inside youThe universe is your only breathSurrender to the present momentWhat’s coming now is all that’s left | There’s a song and a spell. Mid-bass tones stretch, no beat just yet. There’s a voice that cuts through, sounds like a child’s voice maybe. Then Beverly Glenn-Copeland’s spell. The vocals in the background are like a dawn. The aesthetic is contemplative, soft, gentle. This is not what the club is usually like! This is more meditative. Birdsong. More echoing vocal riffs. Staccato notes that warp and climb, out of tune but in a playful way. |

The Remote Access protocol around sound description is also emergent, taking on qualities similar to Bojana Coklyat and Finnegan Shannon’s Alt-Text as Poetry method. In Coklyat and Finnegan’s approach to image description, visual media are not simply straight-forward or objective phenomena. Instead, the ways that a describer understands an image based on their own positionality shapes the aesthetics of the description. This also means that describers can play with the aesthetics of image description, effectively writing poetry. Beyond objective descriptions of sound, Remote Access organizers have taken a poetic approach to sound description. For example, access doula and digital media scholar charles eppley has developed methods of sound description based on their work as a professional sound describer. Party organizer and participant Margaret Fink provided this assessment of the sound descriptions:

I’m deaf and/but I am also a sound user who enjoys music, even if my experience might not be the same as a hearing person. The sound descriptions charles offered were so cool. I remember being drawn to them with relish and curiosity, because they both mapped onto and gave some additional detail/specificity to what I was hearing. I love that [they] attended to the vibe of the music, and I also super appreciated the way [their] very finely-calibrated genre and sound descriptors offered some of the ambiance of the music that might come from cultural context. So I liked knowing that something was an avant-funk cover of a Lady Gaga song, or if the percussion sounded tinny or like it scattered and disappeared. These are all made up memories but capture some of the delight of the sound descriptions.

In other words, sound descriptions integrate both technical and sensory elements to convey the mood, tempo, and feel of the music. Access doula Teresa Suh layers on additional description based on experience with sound description. For instance, at one Remote Access event held as the session “Choosing Ourselves and Each Other: Queer Disabled Legacies, Desires, and Dreams” of the Disability Futures Symposium (July 19, 2021), eppley and Suh each described Phantazn’s “Sweet Sweet Abyss (Vocal Dub).” The descriptions read as follows:

charles: Skeletal yet bouncy syncopated rhythm with murky kick drum, tinny high-hats and soft synth pads; tempo about 130 bpm. Slurred lyrics “let me take you on a journey” contrast the sharp beat, which is lifted up by a glitchy, stretched-out vocal sample acting as a crescendo to a beat drop. Stabbing short synths and syncopated handclaps, punctuated by choppy vocal samples, give this an electro funk feeling. Throughout the song, the beat repeatedly falls away as an ethereal androgynous voice murmurs below, before picking back up to a groove, complemented now by a ravey breakbeat sample. This makes me feel like I’ve had a couple of Red Bulls that haven’t really kicked in yet.

Teresa: A muddy kick and tinny high-hats create a syncopated, strutting rhythm. Overlays of synths softly swell in the background as a voice begins to speak about “a journey” in an ethereal tone. The sound of a sustained harmonic cry emerges out of the ethereal tones, crescendoing into a beat drop. A repetition of short rhythmic synths form a breakbeat. A voice maintains the rhythm of the synths but adds an echo that creates the sense of temporal disorientation. The voice is fragmented into multiple voices. Sounds like we are making our way in hyperspeed in space watching ourselves get split into multiple dimensions, transcending into a space that is not material.

When offered in the chat to participants, the combination of the two descriptions exemplifies collective or participatory audio description method, similar to the image description methods offered by Kleege and Wallin and Coklyat and Finnegan.12 Participatory description involves iterative (and multi-person) descriptions that layer upon one another. In extending principles of image description to sound, access doulas are revealing potentially cross-disability methods of exchange and meaning-making. Across these methods, the labor of producing access is distributed amongst collectives while the objectivity of singular descriptions is not taken for granted as an objective representation of the media described. Instead, description emerges as a tapestry or cacophony of representations. In the case of describing a DJ set, where music and sounds are also layered in complex ways, participatory descriptions by access doulas and party participants mirror the form of the mixed audio content, as well.

Because DJ sets are pre-designed, they lend themselves well to pre-description by access doulas. By contrast, williams facilitated karaoke sessions enabling partygoers to learn and practice description in real time. Each karaoke session focused on two or three songs. Access was not already built into these sessions. Instead, the short and spontaneous karaoke sessions were intentionally crafted to invite cross-disability participation in visual and audio description. Participants described these elements both in the chat and aloud (which was then captioned). The karaoke sessions thus became a playful distribution of labor amongst participants, whereas the access-rich DJ sets were pre-scripted in their descriptions. We watched as access was spontaneously cocreated, an emergent strategy shared between party participants.13 In these unscripted karaoke spaces, experimental access took shape by co-witnessing one another’s access needs, in addition to recognizing our own access needs. Thus, partygoers were offered the opportunity to shift from attendee to active access-maker and provider.

Participation Cards

When people attend parties, they may have different levels of desire for interaction with other people. Some people may want a lot of interaction, while others may want none or may only want to interact with people under certain conditions. In neurodivergent spaces, participation cards are actual cards that are worn like buttons or badges. They are a tool that has been developed to communicate differences in desire for social participation. Building on the tradition of participation cards developed by neurodivergent people in social spaces, moira created Remote Access Participation Cards (Figure 15) as virtual backgrounds that participants could download for parties and/or use elsewhere. Each card offers participants a way to express their level of desired social interaction directly and with ease. Our three Participation Cards are green (“Sososo up for chatting and hanging!”), yellow (“OOO only if I know you!”) and red (“Hmmm not feeling it right now”). The level of social interaction a partygoer is up for is explained by the black text across the top of the card along with the color of the card. Image descriptions with a brief how-to are located on a readable Google Doc in a folder with the downloadable cards. The Participation Card folder is hyperlinked in all our Participation Guides following the Witches ‘N’ Glitches party. Access Doulas are also identifiable by a black, gray, and white Access Doula Card, which is also designed for color blindness. The Access Doula card reminds participants that added support is available. This includes access doulas who, from time to time, need support from other access doulas with negotiating access, as well.

Remote Access Participation Cards invite multiple opportunities for shifting crip social desires and emotions. Partygoers can swap out Participation Cards according to how much or little interaction they desire. A brightly colored abstract leopard print “Just for fun! Make it your own!” card, invites participants to make their own participation card and use it as they like (Figure 16). Participants describe their background images/cards during the party along with providing visual descriptions of themselves.

Participation cards build on neurodivergent access methods to recognize the need for expressing and receiving information about emotional and/or physical access needs in shared spaces. These cards allow participants to be together without neurotypical demands for interaction becoming party norms. Although they are visual elements, their interaction with other accessibility protocols (including written and audio description) makes them into potent tools for cross-disability solidarity.

For williams, who created the participation cards, these tools bear resemblances to the practice of land acknowledgement. Participation cards recognize that the virtual landscapes through which remote access takes place are contested, just as the physical spaces and lands we work within daily are contested. As williams (who is Indigenous) writes in their Territorial Land Acknowledgement, both virtual and physical spaces are built on continued legacies of slavery and settler colonialism.14 While participation cards and Land Acknowledgements themselves do not change these legacies, they are emergent practices that add considerations of consent and negotiation to how party participants interact within the space and one another. Collectively acknowledging the histories of the lands, the support systems that sustain us, and the ways we have come to them is to commit to the on-going process of turning ourselves towards cross-disability and across justice solidarity—this is not something we set at the beginning of an event and move on from. Rather, it is the way we emerge and cocreate across justices together.

Remote Access and Disability Culture

Remote Access invited collaborations across disability experiences, culminating in a cross-disability cultural space. These spaces continue to be significant as the pandemic rages on and opportunities for remote participation are nevertheless taken away. To better understand the significance of spaces for remote access (particularly for immunocompromised people), we invited collaborator Megan Bent to record some reflections on Remote Access. These reflections were recorded on February 2, 2022 and are transcribed below.

I participated in my first Remote Access nightlife event at the Witches’N’Glitches party in the summer of 2020. I was invited by a then- acquaintance and now dear friend, moira williams. Being immunocompromised, I had been at home since March (and still remain at home now almost two years later). As many in the pandemic I had been on numerous Zooms as means of connection but this event, Witches’N’ Glitches, went somewhere else, somewhere deeper, more joyful, and more connective than any online event I had been to. It was centered in crip magic and I felt the invitation to be there as myself as I needed to be, which was new and radical for me. Since then, it has been Remote Access events that have fed and nourished my soul through this pandemic. It has been meaningful to grow closer to my crip community and to experience access intimacy for the first time in my life. To move from being an attendee to access doula and helping to plan and coordinate remote access events (crip karaoke!!!) in the future. It has been disappointing to watch online events and accessible options disappear in the summer of 2021 as calls for a return to “normalcy” grow louder (which, I have a lot of thoughts on that word for another time). But that has just increased my resolve to work to continue creating remotely accessible joy and access intimacy for our crip community. I am truly grateful for those who led the way like moira and Kevin, and not only for the joy and community it’s brought to my life, but also the ways in which it has radically changed my own understanding of access needs and how creating access is a pivotal part of equity, inclusion, safety, leadership, and creativity.

– Megan Bent

The emphasis on disability culture and joy pervades the way that participants comment on Remote Access in private conversations with organizers. Until this point, we have not made a systematic attempt to gather feedback from party participants. In the context of a party, however, distributing a survey could create social or access barriers, distracting from the celebration itself. A more organized planning collective is emerging to address these issues and to solicit feedback about how accessibility measures are working for participants.

Since 2020, the organizers have developed Remote Access as a series of party spaces, gathering opportunities, and access protocols for creating disability cultural spaces that are available across long distances. We have endeavored to make space for emerging practices that address our access needs as we come to understand them in their complexity and change. We have made disability culture the central reference for our methods. Our primary goal has been to invite cocreation in collective access-making. As the party continues to develop through further iterations, our focus on disability and crip community remains central, while we continually seek to expand the boundaries and technologies shaping how we enact joy and pleasure within our communities.

Notes

- The authors identify as disabled and as part of disability culture. williams is an Indigenous, queer, and multiple disabled person. Hamraie is disabled, neurodivergent, trans, and SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African). ↩

- Mia Mingus, “Reflections from Detroit: Reflections On An Opening: Disability Justice and Creating Collective Access in Detroit,” INCITE Blog, August 23, 2010, http://inciteblog.wordpress.com/2010/08/23/reflectionsfrom-detroit-reflections-on-an-opening-disability-justice-and-creatingcollective-access-in-detroit/; Aimi Hamraie, “Designing Collective Access: a feminist disability theory of Universal Design,” Disability Studies Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2013). ↩

- Georgina Kleege and Scott Wallin, “Audio Description as a Pedagogical Tool,” Disability Studies Quarterly 35, no. 2 (2015). ↩

- As this was not a research project with formal surveying and data collection, our archive emerges from material traces and process documents, such as images, text messages and voice memos, transcripts of sound and image descriptions, and other unintentional documentation left behind with each iteration of the party. The organizing team for Remote Access has had a fluid, expansive, and decentralized quality, often blurring the lines between organizer and participant as partygoers are invited into the organizing process during and after each event. The team has included a wide range of disabled people, some of whom identify politically with disability and some who do not. This range includes neurodivergent, physically disabled, Deaf/Hard of Hearing, and chronically ill people, including multiply-marginalized (queer, BIPOC, and working class) people. In this paper, we do not identify individual peoples’ relationships to disability other than our own due to privacy concerns raised by multiply-marginalized disabled participants, who are uniquely at risk of racialized profiling, losing benefits, and medical bias if their identification with disability is made public. ↩

- Aimi Hamraie, Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017); Bess Williamson, “Electric Moms and Quad Drivers: People with Disabilities Buying, Making, and Using Technology in Postwar America,” American Studies 52, no. 1 (2012): 5–29. ↩

- Kevin Gotkin, Louise Hickman, Aimi Hamraie, with the Critical Design Lab, “Remote Access: Crip Nightlife Participation Guide,” March 2020, bit.ly/RemoteAccessPartyGuide. ↩

- The concept of disability justice has been further articulated beyond Creating Collective Access. For example, the performance art collective Sins Invalid, co-led by Patty Berne, wrote the “Ten Principles of Disability Justice.” Patricia Berne, Aurora Levins Morales, David Langstaff, and Sins Invalid, “Ten Principles of Disability Justice,” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 46, no. 1 (2018): 227–230. ↩

- Simi Linton, Claiming Disability: Knowledge and Identity (New York: NYU Press, 1998). Kevin Gotkin, “Crip Club Vibes,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5, no. 1 (2019): 1–7; Sami Schalk, “Coming to Claim Crip: Disidentification with/in Disability Studies,” Disability Studies Quarterly 33, no. 2 (2013). ↩

- adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2017). ↩

- Mingus, “Reflections from Detroit.” ↩

- Hamraie, “Designing Collective Access”; Mingus, “Reflections from Detroit.” But in this sense, it also raises important questions of “access labor” for us.[12. Louise Hickman, “Transcription Work and the Practices of Crip Technoscience,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5, no. 1 (2019): 1–10. ↩

- Kleege and Wallin, “Audio Description as a Pedagogical Tool”; Bojana Coklyat and Shannon Finnegan, Alt-Text as Poetry workbook, 2020, https://alt-text-as-poetry.net/ ↩

- brown, Emergent Strategy. ↩

- moira williams, Territorial Land Acknowledgement, Google Doc, 2019, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1YejoMRvDagKDoXtcyCdGJ652JdGbSUVpg1s9T38lphk/edit. ↩