In response to Zamora and Jäger’s intellectual history critique of my original essay, I reiterate the methodological necessity of grounding a historical study of basic income in a Marxist framework that considers both the organic and conjunctural. This approach illuminates the complexities of basic income as common sense under capitalism while illustrating the limits and opportunities for Left organizing around the idea of basic income.

Responses

UBI as a Tool for Solidarity: A Response to Richard Todd Stafford

I am examining UBI in order to imagine a more egalitarian democracy under capitalism through the redistribution of national wealth that all labor, paid and unpaid, create. I maintain that the redistribution of capital through a UBI cannot be completely dismissed; however, the key would be to remain dedicated to emboldening individual economic agency through bottom-up initiatives while battling for infrastructural changes in a governmental, top-down fashion.

Historicizing Basic Income: Response to David Zeglen

This piece argues that Basic Income is, and has never been, a simple “common sense” or “spontaneous” idea for those who want to struggle against poverty. In fact, it but the product of a profound shift in how we thought about the social question since the late 19th century. A shift that, by the mid-sixties, made cash transfers and the price system the main tool when thinking about redistribution against collective provision or more state-centered approaches.

Response to Lindsey Macdonald’s “We are All Housewives: Universal Basic Income as Wages for Housework”

What types of subjectivities and political actors are emerging around calls for UBI? Lindsey Macdonald’s article, “We Are All Housewives,” eloquently speaks to the concept of universality, while also situating socialist-feminist demands for UBI within specific activist traditions. I pose questions about the distinctions between different socialist arguments for UBI and the political groups that advocate for its implementation: first, what are the differences between autonomist and feminist proposals; and, second, how might we distinguish and evaluate organizations that are fighting for a feminist-socialist UBI?

Naturally Radical? A Response to Kimberly Klinger’s “Species-Beings in Crisis: UBI and the Nature of Work”

In this response to Kimberly Klinger’s “Species-Being in Crisis: UBI and the Nature of Work,” John Carl Baker ties Klinger’s analysis to past Marxist debates about human nature and contemporary appeals to human nature by a resurgent US left. While sympathetic to the idea that UBI speaks to a human desire for free productive activity, he critiques the notion that UBI necessarily illuminates the exploitative wage relations of capitalism. Baker proposes that regardless of the validity of Marxist conceptions of human nature, it is the materialist analysis of social relations that must take primacy in any examination of UBI or similar left policy prescriptions.

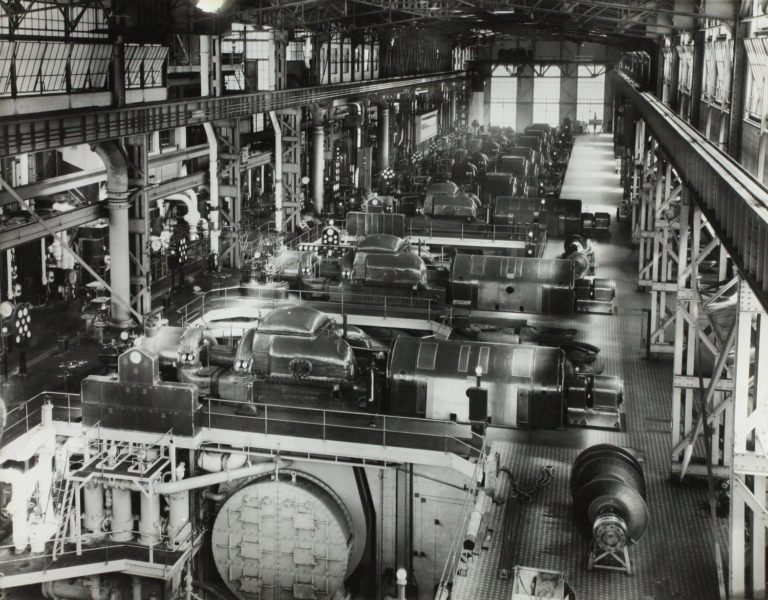

Response to Caroline West’s “From Company Town to Post-Industrial: Inquiry on the Redistribution of Space and Capital with a Universal Basic Income”

This reply critically analyzes the concept of “solidarity” in Caroline West’s account of the role that a Universal Basic Income (UBI) could play in Central Appalachian re-development. I argue that a robust structural form of “solidarity” would necessarily play an essential role in formulating a political bloc capable of implementing an ambitious project like a UBI. In addition to this implicit role of a structural form of solidarity that can connect various communities and constituencies together into a powerful political bloc, Caroline West also articulates an important role for highly local forms of community and solidarity in this region’s transformation. Given the two distinct ways that “solidarity” functions in her account, I raise questions about how the formal features of a UBI relate to both its local and more structural forms.

Toward Alternative Humanities and Insurgent Collectivities

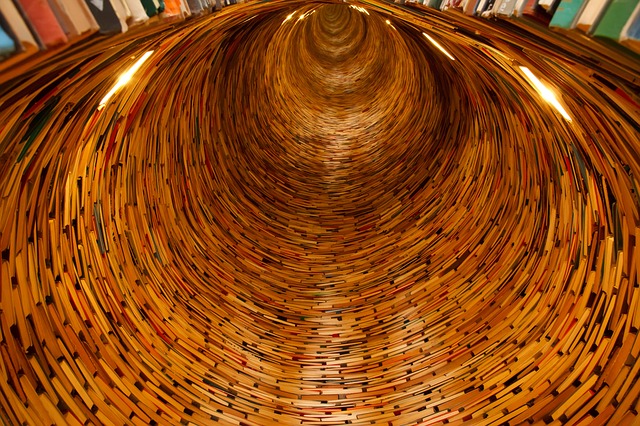

Introduction to Part II of the forum, Emergent Critical Analytics for Alternative Humanities. Here, emergent scholars respond to essays by J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Julie Avril Minich, and Jodi Melamed, each of whom elaborated on the alternative possibilities of dealing with the legacies of settler colonialism, new materialisms, disability, and institutionality in Part I, published in Lateral 5.1.

Ongoing Colonial Violence in Settler States

Response to J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, “A Structure, Not an Event: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity,” published in Lateral 5.1. Jafri articulates how a critical race feminist/queer lens makes possible thinking that sees the repetitions of racialized, gendered, sexualized colonial violence.

The Times of Settler Colonialism

Response to J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, “A Structure, Not an Event: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity,” published in Lateral 5.1. Gniadek approaches settler colonialism via questions of time—asking When is settler colonialism?—which reveals how narratives of national belonging tend to operate, as narrative confrontations that facilitate violence throughout and across time.

Thinking with Melissa Gniadek and Beenash Jafri

In “The Times of Settler Colonialism,” Melissa Gniadek urges me to go beyond the formulation of settler colonialism conceived as a problem of space. She pushes to further consider how Wolfe’s theorization of settler colonialism as structure (not an isolated episode) to examine “not only how histories of invasion do not stop, but also how…

Exploring the Promise of New Materialisms

Response to Kyla Wazana Tompkins, “On the Limits and Promise of New Materialist Philosophy,” published in Lateral 5.1. Shomura mediates upon the promise and possibilities that new materialisms affords in its attentiveness to the material.

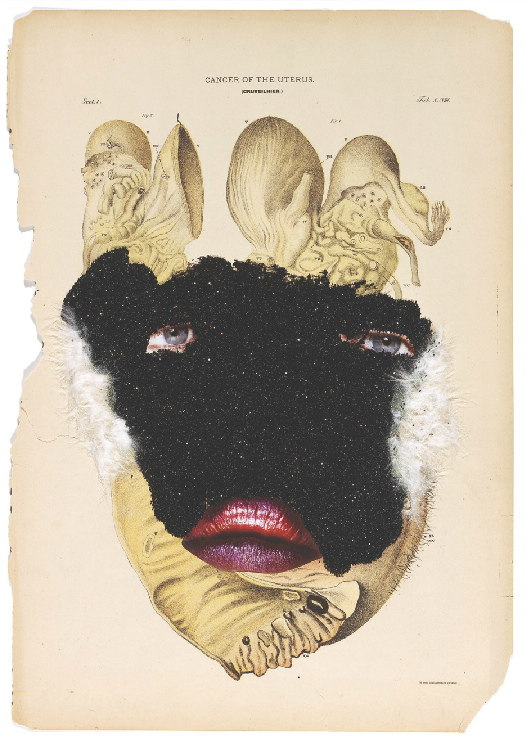

Rematerializations of Race

Response to Kyla Wazana Tompkins, “On the Limits and Promise of New Materialist Philosophy,” published in Lateral 5.1. Huang reassesses the methodological implications of new materialisms by grappling with renewed attention to form in literary studies to articulate the varying processes by which racial difference becomes elided, rematerialized, and remade.

Response to Michelle N. Huang and Chad Shomura

I am very grateful to Michelle N. Huang and Chad Shomura for their extensive engagement with my short and rather off-the-cuff thoughts on the limits and possibilities of new materialism. Their detailed and thoughtful responses extend and flesh out the work that I started to do in my original essay, taking my bullet-pointed aggravation with…

Critical Disability Studies as Methodology

Response to Julie Avril Minich, “Enabling Whom? Critical Disability Studies Now,” published in Lateral 5.1. Schalk calls for a shift in thinking that directly affects action and discusses creating classroom experiences that help students to critique intersecting social structures in their everyday encounters.

Toward a Crip-of-Color Critique: Thinking with Minich’s “Enabling Whom?”

Response to Julie Avril Minich, “Enabling Whom? Critical Disability Studies Now,” published in Lateral 5.1. Kim elaborates upon a crip-of-color critique, which has possibilities to both criticize structures that inherently devalue humans and to take action to work toward justice. Kim’s final call is to identify and act against the inequalities and harm of academic labor, urging readers to take seriously a “politics of refusal” that might help academics of color survive through alternative collectivities.