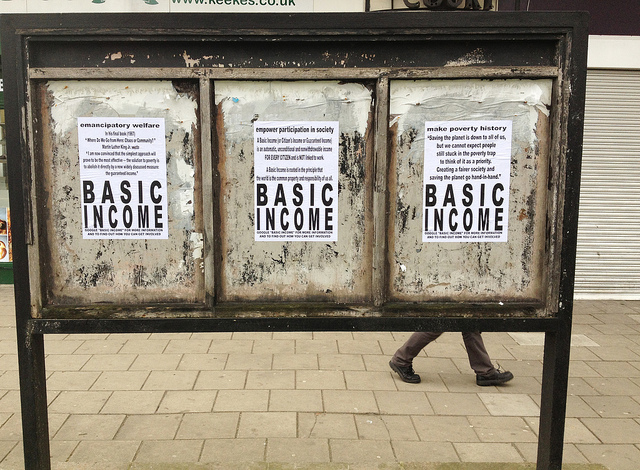

Basic income is an idea almost as old as capitalism itself, appearing very early in the course of its historical development. The emergence of the idea of a basic income in the first few centuries of capitalism’s development in England became inextricably linked to economic crisis. Unsurprisingly, interest in basic income plans have resurfaced yet again in the post-2008 conjuncture. Current debates about basic income often invoke the framework of a morality play about personal responsibility, work ethic, and frugality that obfuscate organic features of the capitalist social formation, such as economic crisis. Therefore, this forum returns to the Marxist approach to answer the persistent questions that basic income provokes, and to help enlarge the Left debate on basic income that exists on the margins of public discourse.

Universal Basic Income

Edited by David Zeglen

Basic income is an idea almost as old as capitalism itself, appearing very early in the course of its historical development. Unsurprisingly, interest in basic income plans have resurfaced yet again in the post-2008 conjuncture. Current debates about basic income often invoke the framework of a morality play about personal responsibility, work ethic, and frugality that obfuscate organic features of the capitalist social formation, such as economic crisis. Therefore, this forum returns to the Marxist approach to answer the persistent questions that basic income provokes, and to help enlarge the Left debate on basic income that exists on the margins of public discourse.

Basic Income as Ideology from Below

Most Left critiques of basic income assume a model of “false consciousness” on the part of basic income advocates. These critiques do not account for how desires for a basic income may also come from the material inversion of social relations that occurs under capitalism. Considered from the vantage point of fetishism and common sense, basic income demands appear rational rather than the product of false consciousness, which in turn informs how the left should organize “good sense” to build a hegemonic bloc.

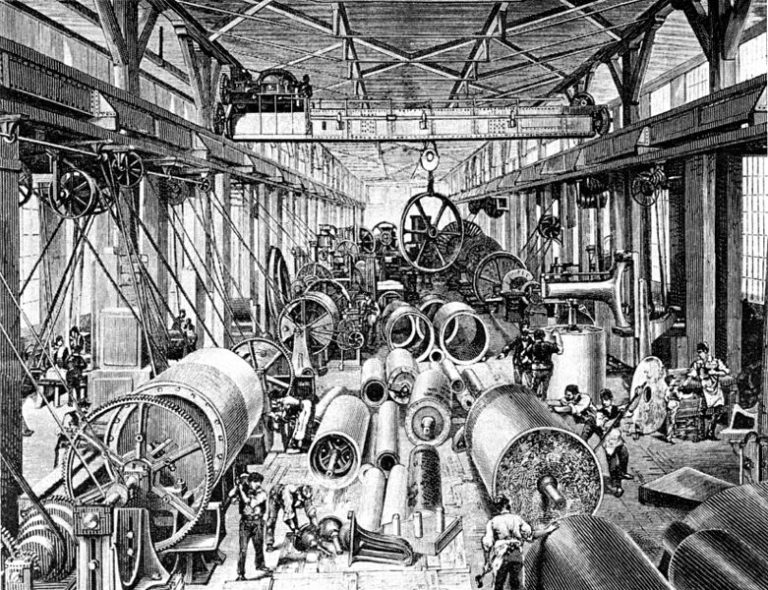

Species-Beings in Crisis: UBI and the Nature of Work

Marx famously argued that labor, under capitalism, alienates humans from not only the products of their labor, but from their very nature. Further, capitalist labor presents a “double freedom” for the worker that is, of course, anything but free: the freedom to either work for an exploitive boss, or to refuse, and starve. UBI would seemingly allow for way out of such a conundrum, but would it also open the door to allow humanity to regain their status as “species-beings”? I explore the idea of UBI as presenting an opportunity for meaningful work and a subversion of the logic of capital. Does UBI indeed grant workers more freedom, or does it merely contribute to the continued denigration of social relations under capital?

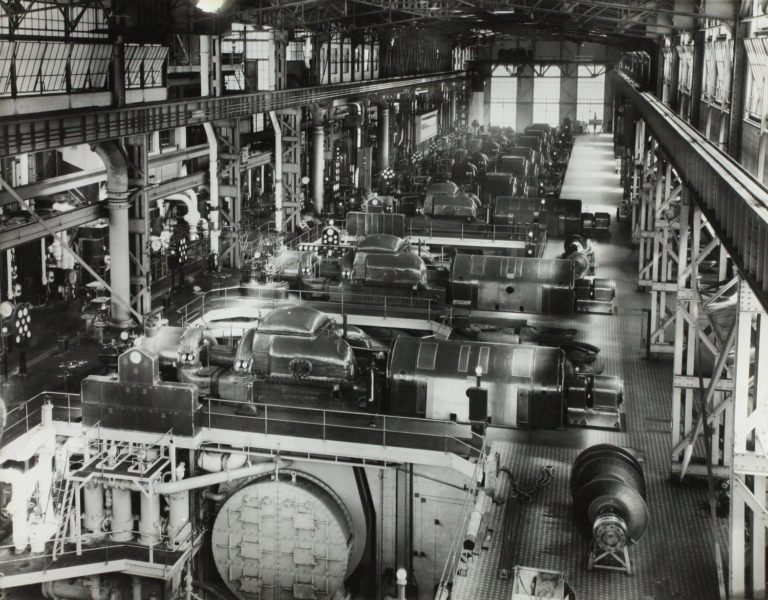

From Company Town to Post-Industrial: Inquiry on the Redistribution of Space and Capital with a Universal Basic Income

This paper considers what effects a universal basic income could have on disrupting social and economic inequality in the tensions of urban/rural divide. She frames her inquiry on the political economy of land and labor in the collapse of coal industry “company towns” and its structural aftermath in Central Appalachia.

We are All Housewives: Universal Basic Income as Wages for Housework

This paper proposes to orient contemporary debates over universal basic income (UBI) to broader social theory in the Marxist and Marxist-feminist traditions. Drawing on theories of labor decommodification, market socialism, and social reproduction, as well as more public-facing debates over policy, the purpose of this analysis is to better clarify the stakes a burgeoning left politics might have in pursuing the demand for UBI. Following key justifications put forward by chief proponents of the Wages for Housework movement for pursuing seemingly impractical, impossible, and politically ambiguous demands, I argue that UBI is best treated as a political perspective with both reactionary and revolutionary undercurrents. Urging caution, not dismissal, I refute more conventional economic analysis leading to common refrains against UBI, and suggest possible ways to bend UBI toward more explicitly socialist aims.

Responses

Historicizing Basic Income: Response to David Zeglen

This piece argues that Basic Income is, and has never been, a simple “common sense” or “spontaneous” idea for those who want to struggle against poverty. In fact, it but the product of a profound shift in how we thought about the social question since the late 19th century. A shift that, by the mid-sixties, made cash transfers and the price system the main tool when thinking about redistribution against collective provision or more state-centered approaches.

Response to Lindsey Macdonald’s “We are All Housewives: Universal Basic Income as Wages for Housework”

What types of subjectivities and political actors are emerging around calls for UBI? Lindsey Macdonald’s article, “We Are All Housewives,” eloquently speaks to the concept of universality, while also situating socialist-feminist demands for UBI within specific activist traditions. I pose questions about the distinctions between different socialist arguments for UBI and the political groups that advocate for its implementation: first, what are the differences between autonomist and feminist proposals; and, second, how might we distinguish and evaluate organizations that are fighting for a feminist-socialist UBI?

Naturally Radical? A Response to Kimberly Klinger’s “Species-Beings in Crisis: UBI and the Nature of Work”

In this response to Kimberly Klinger’s “Species-Being in Crisis: UBI and the Nature of Work,” John Carl Baker ties Klinger’s analysis to past Marxist debates about human nature and contemporary appeals to human nature by a resurgent US left. While sympathetic to the idea that UBI speaks to a human desire for free productive activity, he critiques the notion that UBI necessarily illuminates the exploitative wage relations of capitalism. Baker proposes that regardless of the validity of Marxist conceptions of human nature, it is the materialist analysis of social relations that must take primacy in any examination of UBI or similar left policy prescriptions.

Response to Caroline West’s “From Company Town to Post-Industrial: Inquiry on the Redistribution of Space and Capital with a Universal Basic Income”

This reply critically analyzes the concept of “solidarity” in Caroline West’s account of the role that a Universal Basic Income (UBI) could play in Central Appalachian re-development. I argue that a robust structural form of “solidarity” would necessarily play an essential role in formulating a political bloc capable of implementing an ambitious project like a UBI. In addition to this implicit role of a structural form of solidarity that can connect various communities and constituencies together into a powerful political bloc, Caroline West also articulates an important role for highly local forms of community and solidarity in this region’s transformation. Given the two distinct ways that “solidarity” functions in her account, I raise questions about how the formal features of a UBI relate to both its local and more structural forms.