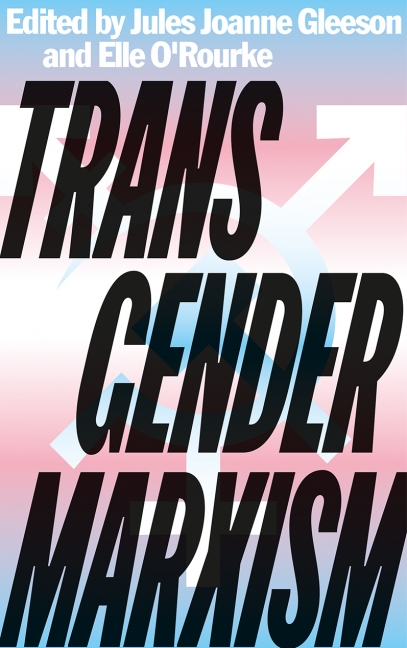

Transgender Marxism is a provocative and groundbreaking union of trans studies and Marxist theory. Exploring trans lives and movements, the authors delve into the experience of trans survival and movement solidarity under capitalism. They explore the pressures, oppression, and state persecution faced by trans people living in capitalist societies, and their tenuous positions in the workplace and the home. The authors give a powerful response to right-wing scaremongering against “gender ideology.” Reflecting on the relations between gender and labor, these essays reveal the structure of antagonisms faced by gender non-conforming people within society. Looking at the history of trans movements, Marxist interventions into developmental theory, psychoanalysis, and workplace ethnography, the authors conclude that in order to achieve trans liberation, capitalism must be abolished.

Keyword: Marxism

Back to Basics with Labor-Power: The Problem of Culture and Social Reproduction Theory

Ted Striphas recently called for a return to the “problem of culture” within cultural studies. This is a political as much as a methodological provocation: “culture” became an object of analysis among mid-twentieth century scholars in dialogue with Marxist accounts of ongoing political crises. Taking a cue from this past, this essay rethinks culture in relation to the ongoing crisis in social reproduction via Social Reproduction Theory (SRT). Within some Marxist feminist currents, “social reproduction” refers to the reproduction of labor-power, Marx’s term for the capacity to work sold on the market in exchange for wages. Marxist feminists have theorized such matters at length via their analyses of the practices undergirding the reproduction of labor-power. SRT is not unfamiliar to cultural studies scholars, but those engaged with it tend to explore the representation of socially reproductive practices within culture rather than the ways culture itself contributes to labor-power’s reproduction. This is unsurprising. Historically, the field has discussed labor-power in terms of its circulation rather than its reproduction, detailing culture’s role in reproducing social systems. Drawing upon Michael Denning’s “labor theory of culture,” recent work in SRT, and Marx, I argue that culture functions in a socially reproductive capacity within the logic of capitalism. In doing so, it casts cultural struggle as a form of social reproduction struggle at the intersection of labor-power’s reproduction and that of the society that requires it. This essay constructs a systematic account of culture’s socially reproductive function before using it to consider its historical expression in the current moment.

1986—The Marxist Disciplining of the Cultural Studies Project

Since its infancy, the pluralistic tendencies of the cultural studies project denied methodological and procedural consistency and resisted any disciplining of cultural studies as an attempt at authoritarian policing. Over the course of the 1980s, cultural studies continued to spread beyond the United Kingdom to Australia and the United States, initially, and the rest of the world soon thereafter. Movements towards the bridging of the longstanding divisions between fact and interpretation—between the social sciences and the humanities—under the sign of a principled approach to cultural democracy saw the Althusserian Marxism characteristic of earlier cultural studies scholarship expanded by way of a critical re/engagement of the works of Gramsci. This period of ideological critique allowed for a bold intellectual, political commitment to the re/conceptualization of culture as a site of class struggle, hegemonic formation, and structural signification. Particularly, the year 1986 saw major strides in this direction with the publication of monumental manuscripts by Stuart Hall, Ernesto Laclau, and Chantal Mouffe.

Review of Culture and Tactics: Gramsci, Race, and the Politics of Practice by Robert F. Carley (State University of New York Press)

In Culture and Tactics: Gramsci, Race, and the Politics of Practice, Robert Carley brings a wide array of theoretical and empirical study to make the claim that Antonio Gramsci was a critical race theorist, that Stuart Hall’s important theoretical contributions like articulation are necessarily Marxist to bring structure and agency, long “opposite ends” of the sociological spectrum together in dialectical terms, for one to build a foundation for his original theories. He does so too when uses Gramsci’s and his own work on race and ethnicity in early twentieth century Italy to bring light to the ideological aspects of today’s social movements of race and class. In doing so through his various methodologies, he introduces his theory of ideological contention to explain who social movement organizations organize their tactics and how those tactics influence how groups organize, or practice ideology. His theory of aporetic governmentality, built of the foundations of Michael Foucault and Eduardo Bonilla Silva elucidate the process of institutional racism and how is manifests at the cultural and individual level, bringing a much needed Marxist lens to the issues of race, class, and social movement theory. Carley succeeds in achieving an interdisciplinary work that encompasses the areas of research needed for scholarly work that not only analyze, but create innovate theories that add to the multiple fields of research.

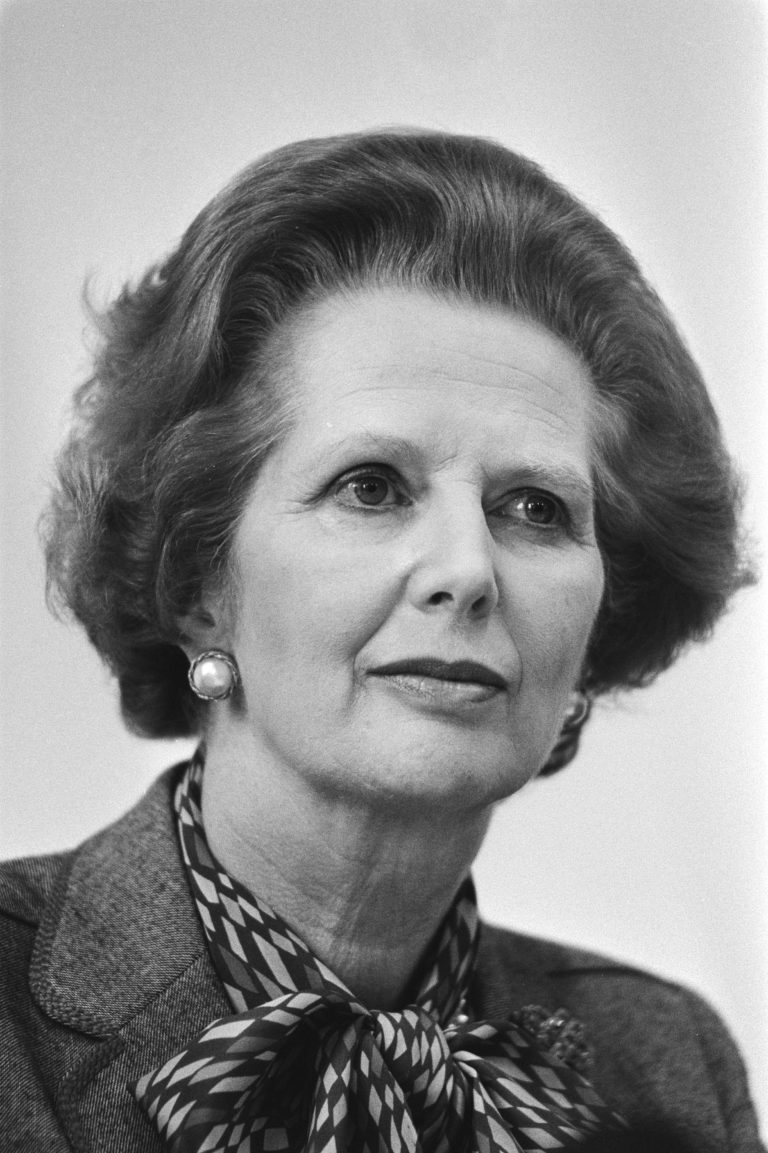

1988–The Crisis in Marxist Cultural Theory

1988 signaled a major year for cultural studies with the publication of several significant texts: The collection of essays Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, the essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” by Gayatri Spivak, and The Hard Road to Renewal, Stuart Hall’s book on Thatcherism. Despite these texts’ divergent purposes, themes, and theories, they can be productively read together for their unique contributions to Marxist cultural theory. In the decades preceding their publication, a resurgence in scholarship devoted to Marxism had emerged, as scholars grappled with both its internal issues as well as its increasingly apparent insufficiency to explain current social formations. As Grossberg and Nelson explain in the introduction to Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Marxism was “paradoxically at once undergoing a renaissance of activity and a crisis of definition.” In this essay, we elucidate how each text contributed to cultural studies and particularly highlight how each intervened on this redefinition of Marxism.

Review of The Cultural Production of Intellectual Property Rights: Law, Labor, and the Persistence of Primitive Accumulation by Sean Johnson Andrews (Temple University Press)

Sean Johnson Andrews’ new book is a timely critique of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) from a critical Marxist perspective. But the true goal of this work goes much deeper into tracing the history of the cultural foundations of the liberal state, private property laws, and labor relations, or what he calls the “reified culture of property.” Regarding the latter, Andrews argues that IPR are only the latest manifestation of this culture. It is an invention functioning like a bandage to hold together the privileged status and power of the capitalist property-owning elite, a power inevitably hemorrhaged by the twin processes of digitization and globalization. In fact, the very existence of IPR, he contends, exposes the fundamental flaws of neoliberal capitalism, presenting us with a unique opportunity. Starting with an examination of IPR, he works backwards to critically interrogate the ideology developed around problematic notions of value creation and the division of labor which both lie at the very heart of the culture of property.

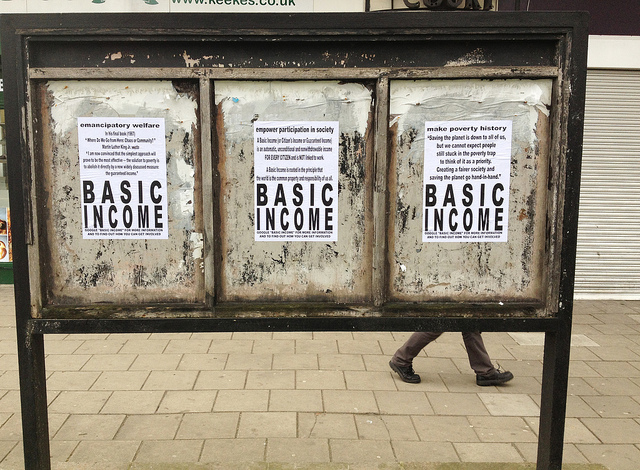

Naturally Radical? A Response to Kimberly Klinger’s “Species-Beings in Crisis: UBI and the Nature of Work”

In this response to Kimberly Klinger’s “Species-Being in Crisis: UBI and the Nature of Work,” John Carl Baker ties Klinger’s analysis to past Marxist debates about human nature and contemporary appeals to human nature by a resurgent US left. While sympathetic to the idea that UBI speaks to a human desire for free productive activity, he critiques the notion that UBI necessarily illuminates the exploitative wage relations of capitalism. Baker proposes that regardless of the validity of Marxist conceptions of human nature, it is the materialist analysis of social relations that must take primacy in any examination of UBI or similar left policy prescriptions.

Dance, Real Estate, and Institutional Critique: Reconsidering Glorya Kaufman’s Dance Philanthropy in Los Angeles

Glorya Kaufman, a philanthropist with a keen interest in dance, has given significant financial resources in recent years to support dance at universities and theaters in Los Angeles. Kaufman’s dance patronage is enabled by a fortune amassed by her late husband. Along with Eli Broad, Donald Bruce Kaufman co-founded Kaufman & Broad in 1957, which became a major purveyor of housing subdivisions in the United States and abroad. In this article, I contextualize Kaufman’s philanthropy within the processes that generated her wealth and the economic role that suburbanization played in the post-war period. In distinction to celebratory narratives that extol patronage for dance, a Marxist analysis of Kaufman’s philanthropy reveals the material connections between concert dance and real estate development. By de-obscuring the source of Kaufman’s wealth, I show how dance funding is bound up in the history of white flight, urban redevelopment, and real estate schemes in Southern California. Practices of institutional critique might prove useful for rethinking Kaufman’s gifts and the political functions of dance patronage.

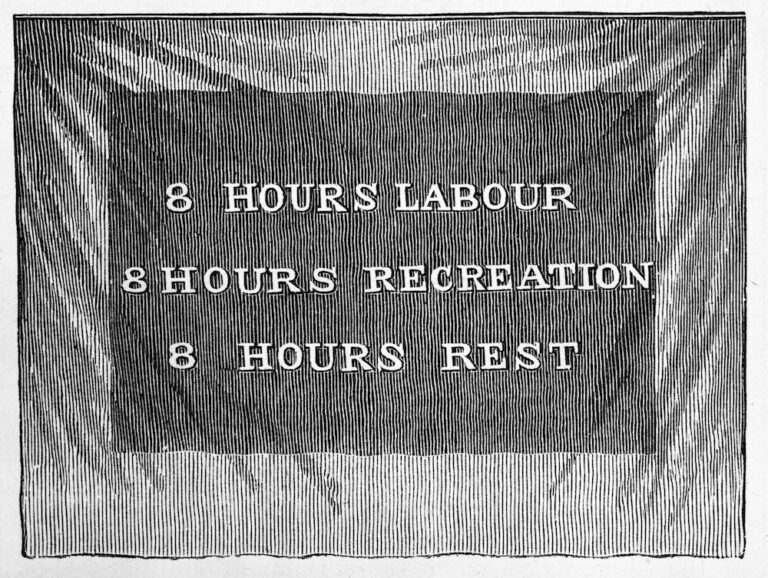

Introduction: Political Economies of Basic Income

Basic income is an idea almost as old as capitalism itself, appearing very early in the course of its historical development. The emergence of the idea of a basic income in the first few centuries of capitalism’s development in England became inextricably linked to economic crisis. Unsurprisingly, interest in basic income plans have resurfaced yet again in the post-2008 conjuncture. Current debates about basic income often invoke the framework of a morality play about personal responsibility, work ethic, and frugality that obfuscate organic features of the capitalist social formation, such as economic crisis. Therefore, this forum returns to the Marxist approach to answer the persistent questions that basic income provokes, and to help enlarge the Left debate on basic income that exists on the margins of public discourse.

We are All Housewives: Universal Basic Income as Wages for Housework

This paper proposes to orient contemporary debates over universal basic income (UBI) to broader social theory in the Marxist and Marxist-feminist traditions. Drawing on theories of labor decommodification, market socialism, and social reproduction, as well as more public-facing debates over policy, the purpose of this analysis is to better clarify the stakes a burgeoning left politics might have in pursuing the demand for UBI. Following key justifications put forward by chief proponents of the Wages for Housework movement for pursuing seemingly impractical, impossible, and politically ambiguous demands, I argue that UBI is best treated as a political perspective with both reactionary and revolutionary undercurrents. Urging caution, not dismissal, I refute more conventional economic analysis leading to common refrains against UBI, and suggest possible ways to bend UBI toward more explicitly socialist aims.

Review of The Social Life of Financial Derivatives: Markets, Risk, and Time by Edward LiPuma (Duke University Press)

Edward LiPuma outlines a sociohistorical theory of the market that positions derivatives trading as initiating a new form of capitalism. The book also confronts the narratives that the financial sector tells itself about the causes and aftermath of the financial crisis, revealing the social relations that underpin the entire enterprise. LiPuma exposes the wild-seeming speculation of hedge fund managers and traders as a rationale that disappears the social aspect of its own ritual induction and relational mode of production and reproduction. An understanding of the social underpinning of financial markets, LiPuma hopes, can lead to a politics of “just optionality” where the same methods for betting on securitized commodities (assets made liquid) like housing mortgages can be transferred into wagers that further the collective good. For Marxists, LiPuma has an urgent message: existing theories of the market are incomplete without an understanding of how financial capital, led by derivatives trading, has transformed the means by which capital reproduces itself.

Editors’ Introduction: Marxism and Cultural Studies

Cultural studies as a discipline and intellectual practice is deeply indebted to Marx, even as the field of cultural studies has contested, revisited, and updated Marx’s work. This issue points to a number of resonant threads currently active under the umbrella of cultural studies and opens possibilities for historical mapping of the many and varied aspects of marxist thought, in and out of the academy. The authors in this issue direct us toward and augment our understanding of the multi-faceted and inextricable links between questions of capital and questions of race, class, and gender power that have been the focus of US research in cultural studies especially within the past thirty years. In this issue, we continue and expand our editorial emphasis on the role of cultural studies in explaining and challenging the ongoing, intersectional significance of material power relations.

Decommodified Labor: Conceptualizing Work After the Wage

A way to think labor after finanancialization, decommodifed labor refers to an emptying out of the same wage relation that nonetheless continues to structure our lives. “Working hard or hardly working” needs a new conjunction: in an age of decommodifed labor, one finds oneself working hard and hardly working. I suggest that decommodified labor offers cultural critics a form for isolating labor today that takes account of its relation to the wage, that may assist in periodizing the capital-labor relation, and that also highlights financial change alongside labor’s durational necessity under capitalism.

Imagined Immunities: Abjection, Contagion and the Neoliberal Debt Economy

This paper addresses the pervasiveness of contagion as a structure of feeling by putting Maurizio Lazzarato’s biopolitics of indebtedness in dialogue with Roberto Esposito’s insight that debt is the very condition of both community and its dialectical opposite, immunity. Where Esposito does not sufficiently engage the role of financialized or neoliberal capitalism within the contemporary crisis, Lazzarato develops a Marxian account of debt that complements Esposito’s “immunitarian biopolitics,” revealing it as an intrinsically capitalist one, and allows us to ground it in contemporary power structures through Marx’s figure of M-M’.

Marxism, Cultural Studies, and the “Principle Of Historical Specification”: On The Form of Historical Time in Conjunctural Analysis

Karl Korsch identifies in Marx’s work what he calls “the principle of historical specification,” the way in which “Marx comprehends all things social in terms of a definite historical epoch.” This work is concerned with this idea and its instantiation in contemporary social theory. With this paper I hope to show how the principle of historical specification has been interpreted within the Birmingham tradition of cultural studies, paying specific attention to (1) the form of historical time implicit in the concept of a “conjuncture,” and (2) the logic of historical periodization that follows from a “conjuncturalist” approach to historical research. I argue that a conception of plural temporality is central to the mode of historical analysis associated with the Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies.