This one is called “Circular Economies and Sustainable Strategies”

As a matter of fact this one is called “Let’s face it, we’re all screwed”

Although I think my mum would call this one “Shushshshshs … I’m trying to chill”

In the realm of kaleidoscopic bananas,

where politicians ride on hovercrafts made of recycled yogurt containers,

and trees grow upside down with roots reaching for the sky,

I see a bulldozer

In a time where elephants roam on stilts

and donkeys sprout wings to soar through the skies,

shadows morph into gargoyles

whispering secrets and conspiracy theories

that defy reason,

I see a bulldozer

Rivers run crimson with the ink of bureaucratic decrees,

mingling with the tears of astonished citizens1

I stretch my arms out in front, bend forward, take a breath, and dive. Muffled voices. Warped mirrors. Turn left. I see a bulldozer. Turn right. I see dust. I consciously activate an altered state of consciousness (a delirium?). I see an arm. [pause] I wonder how I can contribute to thinking with bodies and political economies; at a time when thousands of bodies are on the streets—in refuge, in hiding, in resistance, in protest, in rubble.

A sense of confusion opens new doors, not to the right thing but to something. Something worth momentary chasing. Chasing. Chasing a body. [breathe] I think of my body as a freelance artist, as a migrant, as a traveller, as the precarious type with no pension, no private health insurance, no safety net whatsoever, as the diversity. [Don’t complain. Don’t complain.] Then I think of how much I hate to think of myself and my body as these categories. Then I think “but hate is a strong word.” Then I remember I forgot to say that the poem above is something I wrote for the music and poetry nights I co-run, co-host, co-perform, co-everything with musician Pouya Ehsaei called From the Lips to the Moon. I wrote and performed this poem in July 2023, when a video of an Israeli bulldozer erasing a street in Jenin in the occupied West Bank went viral, at least in my circles and my world of algorithms.2

Now, in October 2023, the media say “a war” has started. Had a war not started when the bulldozer wiped out that street? Or when a cultural centre was bombed a few years back,3 or when another village was turned into a checkpoint or when that child was trembling with fear or when masses of people were expelled from their homes 75 years before?4 Settler colonialism is “a structure not an event.”5 It’s a process.

I cut off my thoughts.

Redirect. Redirect. Blink. Switch. Where were we? Political economies.

Blink.

I switch my mind to the precarity of running art events such as From the Lips to the Moon in the UK. Of the time and energy spent in writing funding proposals, of the horror (pardon my language) that is the Arts Council England project grants application, which when I last applied to and after a resubmission received it, I swore to myself I will never do this to myself, my body, and my psyche again. But I did—in what seems to me as the crumbling financial landscape of the UK art scene, I had to. Colonial turned neoliberal logics lead to constant cuts in arts and culture funds. Similar logics justify the scaling down or closure of arts and humanities courses across UK universities, further distressing the arts community.6 Meanwhile, a headache I’ve been suppressing intensifies. Intensifies. I see my head growing: horns, thorns, eyes, other eyes, pain, worms, worms.

I am a monster, a giant, an arsonist

I am a scissor, a catchphrase, a pain in your ears

I’m a robot, a potato, with saffron and salt

I’m a terrified soul

“I’m a loc’d out gangsta, set trippin’ banger”

I’m a rock rock rock rock rock in my bones

I’m a bee in the wild, craving flowers and love

I’m a suitable choice,

I’m a diversity token, a potential promise

I’m a global talent, an endorsable shite

I’m a doctor of art, if anyone gives a fuck7

Before moving to the UK, as a young artist living and working in Iran, I never made work about my identity. I hardly ever thought about it. I wasn’t brown. I wasn’t foreign. I made performances and wrote about the everyday, the randomness of things heard on the radio and on the streets, the noises of mixing soil with screws, knots and bolts, about my city, about a person lost on the street, about the banality of politics. In the absence of a financial support system for the arts, I wasn’t seen in categories. I didn’t have to explain every artistic choice I made via the colour of my skin or the heritage of my parents or the culture of the carpets. But after migrating to the UK, the distance from home pushed me to create work that was also reflecting, playing with, and subverting my home. Later, through the funding systems of the UK I learned, or tried to learn—sometimes managed, sometimes failed—how to present and fit myself into boxes of diversity, queer, and community, to be conscious of being “the exotic one” as and when needed while trying hard to be anti-exoticization in my work and my thinking. I have succumbed to describing my work and myself through the labels of BAME, SWANA, MENA, POC, BIPOC, minority, Global Majority, Global South, etc. while continuing to practice ways of staying fragmented, nonsensical, and illusive—just as I perceive the world to be.

The constant push towards educating and preaching through the arts, towards finding conclusions, and towards giving manifestos, pressures the imagination. It pressures the possibilities of seeing art by “labelable bodies” (is that a term?) out of these labels. Of seeing other ways of thinking. Other ways of expressing, of moving, of reading. Ways of being otherwise. This pressure kills the in-between space—a space which can be more generative than the space of clarity. Under this pressure, the multiplicities of thoughts and methods; of homes or homelessness; of the lack, absence or reshaping of a sense of belonging’ of the loudness of the surroundings, the smells, the noise, the noise, the distances, the personal, the forgotten, the layers under layers under layers are disregarded in order to shape clear lessons around diversity and inclusivity. But clarity at what cost? Clarity in what shape? For which reality? From whose eyes? For whose pockets? In her book Woman, Native Other, Trinh T. Minh-ha questions the value of correct and clearly-written language—a language of conclusions and closures. For her, clarity aims to “impose order” and communicate “an unambiguous message” creating a power structure that teaches good behaviour through correct language.8 Many “labelable bodies” are pressured to educate others through their art, to be clear, and to be a messenger of a faraway land. But I find more compassion and togetherness in pauses, lapses, open-endedness, blanks, mistakes, lapses, questions, doubts, lapses, echoes. In the confusion.

The experience of becoming a labelable body erases the complexities of the person and reduces them to symbols. Some embrace, cherish, and even monetize this “becoming symbol” process.9 Others challenge it, question it, resist it, or disregard it. The latter would have a lower chance of survival in the art market. In the absence of official censorship, which I lived with in Iran, in the UK I feel the pressure, from art institutions and funders, to fill in the gaps they, and I, see in the healthcare system, immigration system, political system, economic system, education system, employment system, and social security system. And to live up to the image of a symbol—an expectation in which I happily fail.

For those who roam

For those who crossed

For those who resist

For the children touching rubble

For the peace killed every day, on every street

For the pomegranates of your cheeks

Where does the road take us

In what sea

To which port10

In 2021, I spent three months as resident artist at the archives of the United Nations Office at Geneva. My work was around absorbing and responding to the archive via the body. I mostly focused on the documents in the League of Nations archives on Palestine during the British Mandate time. Not conducting historical research per se but exposing myself to miles and piles of administrative documents and seeing how they would land on my body as I touched the papers, as I read words some of which I now assume to be lies.

1924” as observed by the author. Document courtesy of the United Nations Archives at Geneva, photo by author.

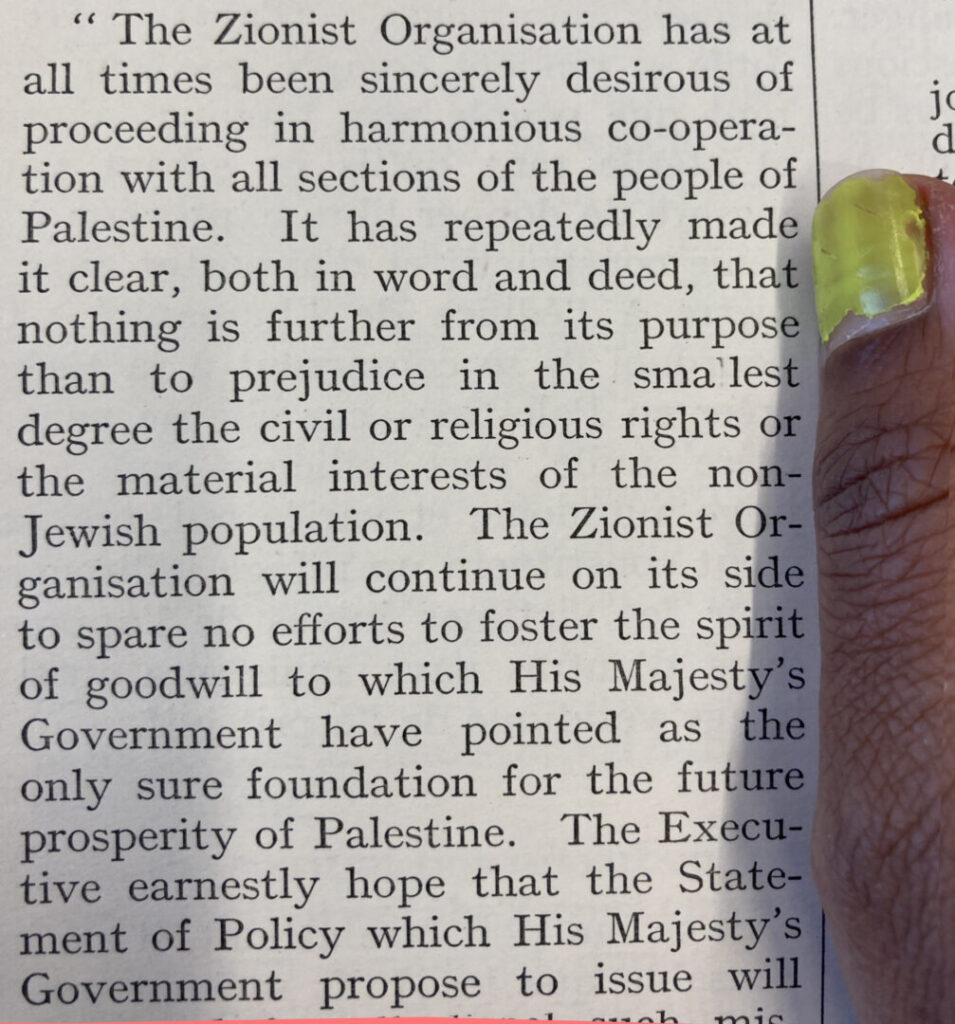

I turn the pages. Day after day. Various correspondences with the Zionist organization.11 Reports on colonization and farming.12 Petitions. Letters. A newspaper celebrating the Jewish Palestine pavilion at the New York World’s Fair (1939).13 A letter with details of torture, murder, and bombardment of houses of Palestinians (1939).14 Photos of UN buildings shelled in Suez city in the 60s,15 a market in Gaza (1959),16 a street view in the old city of Jerusalem (1978),17 a girls’ school in Gaza (1990).18

“The archive,” writes Azoulay, “is first and foremost a regime that facilitates uprooting, deportation, coercion, and enslavement, as well as the looting of wealth, resources, and labour.”19 There, turning the pages and taking steps around the UN office, I wondered how I could allow all this well-documented imperialism, colonialism, propaganda, and what seems to me the failure of international law, to sink into my body—or seep out? How do I sit with evidence of systemic settler-colonialism?20 Or how do I move with these?

The poem above is an excerpt from something I wrote mixing my words with the lyrics of favourite Palestinian songs I collected from my friends from Gaza and their mothers. I read the full text at a performance/intervention I did inside the UN office in Geneva—dancing, moving, walking around Palais des Nations. In the conference halls, meeting rooms, and corridors in between the making of significant political decisions, a camera person and I moved. Micro dances in a place where all body movements are prescribed by the institution. Where most people seem to be temporary acquaintances. Where huge X-ray machines and walls can pop up in a day in the middle of the hallway, change your route, and be gone the next day. This one-hour, semi-clandestine performance was broadcast live on Instagram.

While I was at the UN, my friend Zahid from Gaza was staying at a UN camp on a Greek island awaiting an asylum decision. He told me about the hours and days he waited by the gate of the camp just to be let in. The violence of the inspectors. The mind games. The heart breaking state of the camp after a long and very difficult journey. “Tara habibti, I have so much to tell you. They took my clothes, my power bank, and told me that I should leave my phone or break its camera.” He had chosen to break the camera. The image on our video call was bizarre, cracked, hazy, unrecognizable.

I stop here.

Breathe.

Change the subject.

My phone is flashing.

October 2023. A few notifications. “I have heard back from Mana, she is safe,” “Athar is also safe, her house has been destroyed.” “Zahid’s house destroyed. Anbar’s house destroyed.” These are real people—I have changed their names—who had real homes which are now cavities in the earth.

November 2023. I hear that Zahid and other friends have lost up to 40–50 people each in their families. How is it that we can even say forty–fifty? When do we lose count? When do individuals stop to matter? When do they become a mass? And here I am, trying to memorialize this loss. And Christina Sharpe’s questions echo in my head: “How do we memorialize an event that is still ongoing? […] how does one memorialize the everyday? How does one […] ‘come to terms with’ (which usually means move past) ongoing and quotidian atrocity?”21 Then I wonder how many more people will die in the duration of a peer-review process? How outdated are we by the time we all agree on every word to be published? Or do the continued repetitions of similar actions and the ongoing upholding of similar structures—of oppression, colonization, annexation, and bombardment—render any concerns around the passing of time and further repetitions irrelevant and once again normalize “the situation”?

December 2023. I look at the photos of burnt documents and filing cabinets, broken shelves, a bombarded building, and read the news of the destruction of the central archive of Gaza municipality which was host to “thousands of historical documents.”22

Didn’t I say change the subject?

I change the subject. Grasses grow in abundance in Oklahoma. “Among the state’s 19 endangered or threatened species of wildlife in 2003 were three species of bat […], bald eagle, whooping crane, black-capped vireo, red-cockaded woodpecker, Eskimo curlew, and Neosho madtom.”23

Instagram post on Day 154 of Mishandled Archive, June 4, 2017.

the rivers will flow again. swing.

and the lizards will learn how to swim again. swing.

and from hot ashes tall trees will grow. swing.

and smiling women will throw flowers on their heads. swing.

no mourning. swing.

no pile of broken arms, legs, in the wasteland. swing24

I invite the audience to swing. Hold their arm up, hang their body from it, and swing. The project is called Mishandled Archive. A year of dispersing family photos and documents in public places and making dances for each act of dispersal. Every day. 365 days. 2017. Later accumulating into one large scale performance, in theatres and outdoors, in parks.

“Forget about the heat that killed the baby, swing, forget about the thirst.”25 Your arm lifts you up. Gravity pulls you down. A step to the left. A step to the right. The trees start to move. Muscles around the lips start to contract. Smiles start to appear. Other smiles start to appear. Bodies start to rearrange. One arm at a time. The landscape is rearranged, one body at a time. No pile of broken arms, legs, in the wasteland. The image of limbs, bodies, dust-covered hair, eyelashes, and clothes found in a mass grave in southern Tehran after a massacre of political prisoners in 1988 keeps coming forward in my vision.26 I try to push it back. Swing.

On day 154 of Mishandled Archive, in a photo placed on a tree, a two dimensional woman, (dead?,) black and white, is looking at the children playing in the park decades after losing her daughter. Cause of death: dehydration. But we swing. We swing to move on. We swing to activate. We swing to turn loss into movement, into togetherness, into waves, into change, one limb at a time. A few hours, or a day later, this photo will fall. Or it will be taken by the wind, or a child. But in its momentary collision with some children in North London, it creates a new story to tell and a new way of telling the story of the woman running to find a doctor in the scorching sun for a child who will die soon. The loss generates connections and imaginations. The loss makes us move. Two decades after the 1988 massacre in Tehran, state sponsored bulldozers flattened parts of the cemetery, of the mass grave, for trees to be planted. To suppress the bones and the memories, to deny the past. They make a park but I see a bulldozer.

Notes

- Tara Fatehi, excerpts from a poem written for and performed at From the Lips to the Moon (2023). ↩

- Brian Osgood, Umut Uras, Zena Al Tahhan, and Farah Najjar, “Jenin Updates: Palestinian Deaths Rise, Israeli Raid Continuing,” Aljazeera, July 3, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/liveblog/2023/7/3/jenin-attack-live-israel-kills-eight-palestinians-tensions-high. ↩

- Maha Hussaini, “‘Art Is a Form of Resistance’: Israeli Air Strikes Destroy Gaza Cultural Centre,” Middle East Eye, August 11, 2018, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/art-form-resistance-israeli-air-strikes-destroy-gaza-cultural-centre. ↩

- For more on the expulsion of Palestinians see Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oneworld Publications, 2007). ↩

- Patrick Wolfe, Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event (Continuum, 1999), 2. ↩

- Some of the UK universities that have cut or downsized art and humanities departments are University of Roehampton, Goldsmiths, Kent, East Anglia, and Queen Mary. ↩

- Tara Fatehi, excerpts from a poem written for and performed at From the Lips to the Moon (2023). ↩

- Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other ( Indiana University Press, 1989), 16–17. ↩

- For example see Shohreh Shakoory’s critique of the exhibition of the works of Shirin Neshat as a symbol of Iranian women during the Woman, Life , Freedom movement in Iran. Shohreh Shakoory, “Representation of Disobedient Bodies: A Critical Reading of Shirin Neshat’s Visual Language,” NO NIIN Magazine 16 (2023), https://no-niin.com/issue-16/representation-of-disobedient-bodies-a-critical-reading-of-shirin-neshats-visual-language/index.html. ↩

- Tara Fatehi, excerpts from a poem performed as part of In Observance (2021) a performative intervention at the United Nations Office at Geneva. The poem is a collage of Tara’s words and the lyrics of a few Palestinian songs. ↩

- “The British Mandate for Palestine—Various Correspondence with the Zionist Organisation,” United Nations Library & Archives, Geneva, 1924–1926, https://archives.ungeneva.org/the-british-mandate-for-palestine-various-correspondence-with-the-zionist-organization. ↩

- “The Establishment in Palestine of the Jewish National Home: Memorandum Submitted by the Zionist Organisation to the Secretary General of the League of Nations for the Information of the Permanent Mandates Commission,” United Nations Library & Archives, Geneva, 1924, https://archives.ungeneva.org/the-establishment-in-palestine-of-the-jewish-national-home-memorandum-submitted-by-the-zionist-organization. ↩

- The Jewish Daily Forward, June 4, 1939, United Nations Library & Archives, Geneva. ↩

- Jamal Husseini, “Letter to the President of the Permanent Mandates Commission, The League of Nations,” in “Palestine – Protestations against the British White Book,” United Nations Library & Archives, Geneva, 1939, https://archives.ungeneva.org/palestine-protestations-contre-le-livre-blanc-britannique. ↩

- “A view of OP MIKE in Suez City, 17 April 1973,” photograph, UN Truce Supervision Organisation in Palestine (UNTSO), from United Nations Library & Archives, Geneva. ↩

- “A market in Gaza, April 1959,” photograph, United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF), from United Nations Library & Archives, Geneva. ↩

- John Isaac, photographer, “Old City of Jerusalem, 12 April, 1978,” photograph, from United Nations Library & Archives, Geneva. ↩

- John Isaac, photographer, “Girls’ School in Gaza, December 1990,” photograph, from United Nations LIbrary & Archives, Geneva. ↩

- Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Verso, 2019), 169–70. ↩

- For a look at the use of the settler colonial analytic in Palestine, see “Israel’s Illegal Occupation of Palestinian Territory, Tantamount to ‘Settler-Colonialism’: UN Expert,” UN News, October 27, 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/10/1129942; and Brenna Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah, “Acts and Omissions: Framing Settler Colonialism in Palestine Studies,” Jadaliyya, January 14, 2016, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/32857/Acts-and-Omissions-Framing-Settler-Colonialism-in-Palestine-Studies. ↩

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, 2016), 20. ↩

- Nadda Osman, “Israel-Palestine War: Israeli Forces Destroy Central Archive of Gaza City,” Middle East Eye, December 7, 2023, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-palestine-war-israeli-forces-destroy-central-archive-gaza-city. ↩

- Read more on the flora and fauna of Oklahama at “Flora and Fauna—Oklahoma,” City-Data.com, 2024, https://www.city-data.com/states/Oklahoma-Flora-and-fauna.html. ↩

- Tara Fatehi, excerpt from a text for the performance Mishandled Archive (2019). ↩

- Tara Fatehi, Mishandled Archive (LADA, 2020), 97. ↩

- For a history in Farsi and photographs of Khavaran cemetery, see Monireh Baradaran, “Tarikh-e Tasviriye Khavaran az 1360 ta Emrooz” {A visual history of Khavaran from 1981 to today}, BBC, May 3, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/persian/blog-viewpoints-61623750. ↩