Lateral’s Theory Thread offers essays that critically explore the relationship of carceral and educational institutions—but not as alternatives to one another as often has been assumed in various kinds of social activism. The authors of these essays, Sora Han, David Stein, Shana Agid, Gillian Harkins and Erica R. Meiners, assume the tightly knotted interrelationship of prisons and schools and instead address the question posed by Han: is there something, being affirmed in the identity or identification as a “prison abolitionist” today?

Theory

Abolition: At Issue, In Any Case

Toward what does the “prison abolitionist” identity or identification strive? This thread is organized primarily around Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s essay, “The University and the Undercommons: Seven Theses.” And we think there is not a better place to begin staging the relation between abolition and that to which we refer as “teaching”, with all the compromised valences such work can carry given the state of the educational system today. Indeed, as if to answer the above question about whether there is something affirmed by prison abolitionism, Moten and Harney seem to answer “yes”, there is something. In this essay, I would like to explore this “yes” as it emerges in Moten and Harney’s essay, and how it might unfold in how we imagine our engagements with law.

Making Anyway: Education, Designing, Abolition

This essay aims to raise some provocations and questions about the practice of attempting to teach abolition in universities and colleges that are embracing the notion of the duty of the university to the “community,” and pursuing the deep institutionalization of “civic engagement” curricula and programs, all while offering the promise of an opportunity to “do good” (and do well – i.e., still get a job).

Full Employment for the Future

Who deserves what types of entitlements? On what grounds? In this moment of rampant and structural joblessness, there is an increasing critique of universities for their failure to create appropriate routes to employment for their graduates who are borrowing increasing sums of money to attend. Do these good students, who make, what President Obama has dubbed “good choices,” deserve jobs? If so, why only them? Or, with the extreme wealth of the U.S., should these good students, along with the bad, and everyone else, be entitled to a job or income? And what do employment rates for undergraduates have to do with the university anyway?

Beyond Crisis: College in Prison through the Abolition Undercommons

This thread explores inter-relationships among institutions of higher education and prisons. We focus in particular on teaching and learning – the hallmarks of college in prison programs – as they relate to research and administration within and across universities/colleges and prisons. Our aim is to contribute to broader structural thinking about how we can work in college in prison programs most ethically and in ways that contribute to prison abolition within and across campus and prison settings.

Introduction: In Search of Digital Feminisms

Edited by Katherine Behar and Silvia Ruzanka, In Search of Digital Feminisms includes five essays and the editors’ introduction that suggests we play with the shift from surfing to searching to what is fast becoming the offer, if not the intrusion, of piles of unrequested information. But In Search of Digital Feminisms is not an exercise in melancholia, longing for better digital days now past or for lost feminist horizons. It is a search, having already arrived at a destination, a before and an after all at once, the lost origin that always points to the work of an originary mediation or modulation, if not digitization. In other words, these are not anti-technology works; these are works seeking rather to find ways to creativity and multiplicity in identity and practice that can be an intervention into the contemporary scenes of feminisms and the digital. Although primarily offered as texts, the works that follow point to the need to make theoretical interventions a matter of practices, a matter of interactive mediation, a doing, if not a doing with others.

Ungoogleable: In Search of Digital Feminisms

We begin our search for digital feminisms with the following terms: an acknowledgment that “search” represents an ambition which must fail. Siri’s failed searches only scratch at the surface that Siri is.

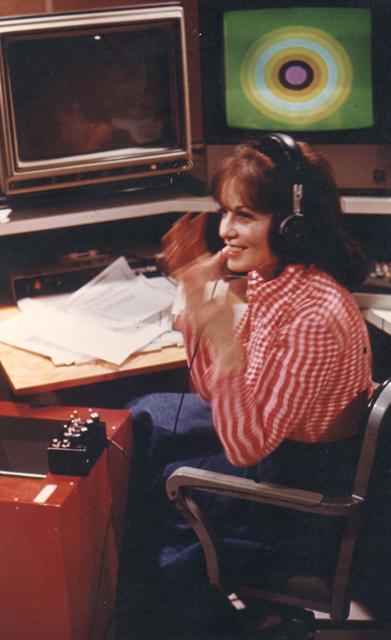

“Up for Grabs”: Agency, Praxis, and the Politics of Early Digital Art

In its infancy, digital art was, as artist and writer Anne M. Spalter enthusiastically put it, “up for grabs.” But how did women artists overcome the fallacy that computer technology was inherently masculine? And why did computing become a kind of sanctuary for some women artists? I will show that the indeterminacy and flux that permitted freer agency, was reflected in the computing field as a whole. Over time, anti-computer sentiment, which affected all artists using the medium, would prove so pervasive that it often eclipsed the sexism later suffered by women.

In Search of Digital Feminisms: Digital Gender & Aesthetic Technology

What is it that influences girls’ choices of new technology? How is digital creativity affected by gender norms? “Digital Gender & Aesthetic Technology” aims to make visible females as creative developers of the Internet and new technology, through interviews with students, artists, project managers, and entrepreneurs. The prevailing social norms appear to be reflected on the Internet as “digital gender norms,” where girls and boys prefer apparently different communication tools. While working with the question of “digital gender,” I have developed the hypothesis of “Aesthetic Technology,” namely that girls often have an artistic approach towards technology. Girls mainly learn technology for a personal reason, planning to create something once they have learned the technique, and their goal often have aesthetic preferences. The question of girls “becoming technical,” is more complicated than one might first think, in relation to gender. Even though young girls are often just as interested in technology as young boys are, it is difficult for them to keep or adapt their technical interest to normative femininity in their teens. Another problem is that expressions of technical competence or innovation, which do not correspond to the predominant male norm, might be hard to recognize. Females who study within the field of creative digital technology often begin their career by struggling with questions of equality, instead of just practicing their profession.

BOT I

“BOT I” is a radical monologic mash-up of autobiographical material from Pilar’s childhood in a computing family and her passions for and against technology, cut in and through the texts of Samuel Beckett’s “Not I” and Isaac Asimov’s I Robot. This article includes the script of the performance Pilar presented at the Radical Philosophy Association Conference in Eugene, Oregon on November 13, 2010 and images from a 2011 performance. Ruthless in its refusal of all gentility and tact, and insistent in its feminist critique, Pilar’s script reveals the blind spots that capitalist techno-culture reserves for ethics and the body.

Meditations on the Multiple: On Plural Subjectivity and Gender in Recent New Media Art Practice

In this text I revisit a multi-venue exhibition I co-curated with Susan Richmond, a professor of Art History at Georgia State University and independent curator Cathy Byrd. “Losing Yourself in the 21st Century” explored how contemporary women artists articulate notions of gendered subjectivity through new media in a social context where notions of a singular and stable self are constantly undermined through the now widespread negotiation of multiple identities that people experience online. We developed a blog that was utilized as a call for participation for the exhibition and also as a platform through which we could engage in dialogue with the artists and for the artists to respond to each other’s work. The blog also served as a particularly useful tool for a feminist project such as Losing Yourself, as it afforded transparency to the collaborative curatorial process. We selected thirteen artists to feature in exhibitions at the Welch Gallery at Georgia State University in Atlanta (October–December 2009) and Maryland Art Place in Baltimore (February–March 2010). The artists included were Ali Prosch, Susan Lee Chun, Katherine Behar, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Amber Hawk Swanson, Noelle Mason, Saya Woolfalk, kate hers, Shana Moulton, Amber Boardman, Stacia Yeapanis, Renetta Sitoy, and Milana Braslavsky.

In Search of a www.analogfeminism.net: Starting with Three Contrarian Concepts via Mother-Daughter Machines to Come

Analog feminism (AF) and digital feminism (DF) are two sides of the same coin; or, multiple twin sisters joined at the hip. Skating from René Descartes to Kara Walker, she asks us “to go gray between zeroes and ones.” Reverting from the digital to its ancestral digit, a finger, Lee uses text and textuality to point out a multiplicity of directions, all of which refrain from a directive. In a series of “posts” negotiating, inheritance, reference, and influence, the daughter searching for the mother returns to sender. Whatever the case, we, or at least one of us, are here to focus on and fly with what’s left uncoordinated in—and connecting—all that’s (to be) digit-alled in the evolving idioms of feminist discourses.

Introduction: Theory and Method

The Theory and Method Thread of Lateral launches its first publication with two essays, one by John Mowitt of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at University of Minnesota and one by Jared Sexton, Director of African American Studies, School of Humanities at University of California Irvine. Together their essays along with responses by Christina Sharpe of American Studies at Tufts University, Adam Sitze of Black Studies and Law, Jurisprudence and Social Thought at Amherst College and Morgan Adamson of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at University of Minnesota, all take theory to one of the most pressing, worldly and yet intimate, of issues faced by each of us, whether working in and/or outside the academy: that is, the conditions of study, or studies, in the University.

The Humanities and the University in Ruin

Mowitt’s essay puts before us in terms of work or, as Mowitt puts it, ‘re: working’ the work of study, scholarship, and research under the contemporary conditions of ‘biopolitical contol’ or neoliberal structural adjustment of the academy. Mowitt warns against reducing the issue of study to complaints of poor pay and poor working conditions and therefore holds the issue of the labor of study on a fine line between the refusal of the work of study altogether and the insistence on simply enjoying the study that we are required to do or paid to do. Mowitt is not denying the poor conditions under which so many of us work for insufficient pay in and outside the University; he rather is warning us about moving too quickly off the fine line between refusal and enjoyment of the required or paid work of study. He is arguing instead for the value of study as a labor of the negative. Mowitt then takes some elegant last moves to turn this return to the labor of the negative into the work of affirmation, thought affirming itself; he thereby moves beyond the dialectic and the Euro-centric Hegelian tradition of progress to affirm instead the immanent unfolding of mindfulness or thoughtfulness, an unfolding of an affective labor that bears within it the in-excess of measure, the yet-incalculable excess of the current calculability of value. This makes the re: working of study not merely a matter of the human or the humanities but of the technical/human medium we fast are becoming, and which we are coming to know we always have been, as has the University.

Response to “The Humanities and the University in Ruin”

In his response to Mowitt, Morgan Adamson sharply reminds us that working conditions and remuneration for work, not to mention layoffs, hiring freezes and slashing of benefits, certainly are pressing concerns. Offering a quick survey of some of the horrid details of the work expected of research assistants in science labs, Adamson also softens the distinction implied in Mowitt’s focus on the humanities as against the sciences.