Abstract This article discusses the sociocultural context in South Korea, which has intensified anti-refugee racism especially since 2018, with the arrival of Yemeni refugees fleeing the war. Park Kyungjoo describes how dual racism encompassing institutional racism and what he calls “citizen-protecting” racism shapes the current conditions of anti-refugee sentiment in South Korea. First, South Korea implemented a refugee act in 2013, in its attempt to catch up with what it perceived as a “global standard.” However, unstable bureaucratic barriers as well as budget cuts and underutilization have left refugee applicants in an inhumane condition and resulted in a perpetually low refugee recognition rate. This is worsened by anti-refugee groups’ “citizen-protecting” racism, which was fueled by the center-left government’s failure to clearly protect refugee rights while strengthening the social safety net for the Korean public. Mobilizing Islamophobic, racist discourses about refugees, these anti-refugee groups, ranging from church groups to politicians, while hard to identify as a singular force, act based on a common interest in right-wing nationalism and the protection of Koreans. Park Kyungjoo calls for multidimensional solutions involving structural changes, institutional changes, and curricular changes in public education, to help the country challenge the current concept of citizenship and democracy.

들어가며

한국사회에서 난민에 대한 인종주의적 차별은 2018년 500여명의 예멘난민이 제주도에 입국한 이후 본격화 되었다. 이것은 매우 큰 변화였다. 국제사회에 난민권리의 보장을 공식적으로 표현했던 90년대 초반과 2013년 당시에는 이와 같은 집단적 반대를 한국사회 어느 곳에서도 찾아볼 수 없었기 때문이다. 물론 2018년 이전에도 외국인혐오와 함께 난민에 대한 편견과 차별의 시선은 존재했지만, 이러한 인식흐름들이 전체 사회에 영향을 미치거나 사회의 위험으로 관찰된 적은 없었다. 반면 2018년 5월의 풍경은 사뭇 달랐다. 사실상 난민에 대한 권리를 보장하지 말자는 국민청원에 70만 명의 국민들이 동의한 것을 시작으로, 난민의 존재와 권리에 대한 집단화 된 부정이 2018년 하반기까지 뜨겁게 이어졌다.

코로나 이후, 그때와 같은 집단화 된 차별과 반대의 흐름은 등장하지 않고 있지만, 난민에 대한 제도적 배제나 차별의 논리는 계속되고 있다. 재난지원금에서 난민을 배제한 일이나 아프가니스탄 지역의 난민들에게 ‘특별기여자’라는 호칭을 통해 ‘난민인정 없는 비호의 경로’를 창설한 사건은 최근의 주요 사례이다. 전자가 지구적 재난의 상황에서도 작동되는 한국사회의 난민에 대한 노골적 차별을 보여준다면, 후자는 국가에 대한 기여와 능력의 여부를 비호의 조건으로 연결시켰다는 점에서 정교화 된 난민차별을 보여준다. 후자가 문제시 되는 것은 난민집단 내부의 차등화를 전제하기 때문이다.

이 글은 한국사회의 난민차별을 주도하고 있는 두 집단, 즉 한국정부와 반-난민세력의 인종주의에 대해 기술할 것이다. 난민에 대한 인종주의는, 그들이 난민이기 때문에 가해지는 폭력이자, 같은 이유로 인해 사회적으로 용인되고 문제시되지 않는 폭력을 의미한다. 위 집단들의 인종주의는 방법과 가치의 차원에서 제도와 ‘국민보호’를 매개한다는 점에서 제도적 인종주의와 국민보호의 인종주의로 규정될 수 있을 것이다.

제도적 인종주의

배경: 난민협약과 난민법의 문제점

90년대 초반 난민협약의 가입을 시작으로 한국에도 난민보호제도가 시작되었다. 하지만 이것은 난민보호에 대한 정부의 깊은 철학에 기초한 것이라기보다, 한국을 국제화하는 과정에서 도구적으로 활용된 측면이 컸다(한국 정부는 이 시기 이러한 실천을 글로벌 스탠다드라고 불렀다). 이러한 배경 때문에 구체적인 난민권리 보호에 대한 큰 그림은 마련되어 있지 않았다. 가장 기본적인 난민인정 절차의 신속성, 투명성, 공정성이 제도화 되지 않았고, 난민신청자의 생계 및 난민인정자의 복지 역시 체계적으로 보장되지 않는 등의 문제점들이 드러났다. 이 시기 가장 큰 문제는 난민심사제도가 출입국관리법 내부에서 운영되었다는 것이다. 이것의 한계는 분명했다. 즉 출입국 관리의 논리가 난민권리를 압도할 가능성이 상례적으로 존재한 것이다. 법 위상학적 차원에서 보면 이것은 국제법이 국내법의 논리에 의해 축소되거나 제한되는 것을 의미했다. 그리고 2013년 시행된 난민법은 독립된 인권법으로 분화되었지만, 이와 같은 한계와 문제점들을 여전히 안고서 시작된 측면이 있다.

난민법을 구상하고 제정할 당시 시민사회가 지적한 대표 문제들은 다음과 같았다.

①출입국항 난민신청에 관한 조항(난민법 제6조)

②간이절차 규정(난민법 제8조 제5항)

③인도적 체류자와 난민신청자 처우 규정 미비(난민법 제39조-제44조).

이에 대한 우려는 난민법 시행 이후 거의 곧바로 현실이 되어 나타났다. 먼저, 출입국항 공무원들의 행정남용을 막기 위해 만들어진 간이심사는 실질적인 심사가 되어 난민들의 심사기회를 박탈하는 결과를 가져왔다. 공항난민들은 이러한 제도의 산물이다. 다음으로, 한국정부는 2014년 시리아난민들을 기점으로 인도적 체류자에 대한 허가를 늘렸지만, 이것은 이들에 대한 다양한 취업기회나 기초생활보장을 전혀 마련하지 않은 상황에서 진행한 일이었다. 따라서 많은 수의 인도적 체류자들은 자구책을 발휘해서 살아가야 했다.

위 사안들을 개정하기 위해 2015년부터 ①출입국항 제도를 개선하는 안 ②인도적 체류자의 처우를 개선하는 안 ③난민심사과정에서 당사자의 권리보장을 강화하는 내용 등의 개선안이 다수 발의된 바 있다. 하지만 이러한 시도는 2015년 테러방지법의 제정을 정당화 하는 논리에 난민에 따른 국가안보의 위협 등이 동원됨에 따라 통과되지 못했다.

낮은 인정률

한국정부의 출입국(국경)관리의 논리가 국제법이 정한 권리를 제약하는 상황의 대표적인 지표는 낮은 난민 인정률을 들 수 있다. 이것은 OECD국가들과의 비교를 통해 보다 분명히 파악된다. 선진국으로서 한국정부의 이러한 실천을 뒷받침하는 것은 남용적 난민, 허위 난민, 가짜 난민 등의 담론이다. 정상화 되지 않은 난민제도는 쉽사리 모든 걸 난민의 탓으로 돌린다. 하지만 난민들은 국제사회에 대한 한국정부의 약속만을 믿고 이곳을 찾아왔을 뿐이다. 다음 표에서 드러나듯이, 낮은 인정률은 한국정부가 약속을 이행하지 않고 있다는 명백한 증거이다.

정상화 되지 않는 난민심사제도

한국정부의 난민심사체계는 여전히 정상화 되어 있지 않다. 심사적체가 심각하며, 신청자 대비 담당 공무원의 수가 턱없이 적다. 또한 절차상의 정의들이 무너지는 사건들이 계속 발생되고 있다. 한국정부는 초기부터 심사적체를 해소하기 위한 방안들에 노력을 기울였다. 하지만 이것은 심사체계의 조건들을 확충하고 정상화하는 것이 아닌 속도를 높이는 방법으로 진행되었다. 정부가 찾아낸 답은 ‘신속심사유형’을 분류하여 이 유형에 속한 신청을 빠르게 불인정하는 것이었다. 하지만 이 유형에 대한 정부의 분류기준에는 문제가 많았다. 대표적인 난민사유에 해당되는 신청(족장승계, 컬트 등)과 기준을 명확히 세울 수 없는 남용적인 재신청 등이 포함되어 있었기 때문이다.

속도를 통해 심사적체를 해결하려고 한 한국정부의 기조는 다수의 재 신청자를 양산했고, 심지어 법무부 내부에서는 다수의 난민신청자들의 난민면접조서가 조작되는 인권침해 사건이 벌어지기도 했다. 국가인권위원회와 난민인권센터는 1-2천 건의 조작을 추정하고 있다.

공항난민, 인도적 체류자, 재신청자

위의 언급처럼 공항난민, 인도적 체류자, 재신청자는 모두 정상화 되지 않은 한국 난민제도의 산물이다. ①공항난민은 한국정부에 의해 난민신청의 권리를 박탈당한 형상이며, ②인도적 체류자는 한국정부의 난민인정 우회 전략이 낳은 애매모호한 지위이다. ③재신청자는 한국정부의 낮은 비호의지를 온몸 그대로 드러내는 존재들이다. 이들에 대한 종합적이고 장기적인 복지계획은 존재하지 않는다. 한국에서 난민인정을 받지 못한 난민들은 복지 대신 정부의 정책공동화가 만든 (언제든 종료될지 모르는) 불확실한 대기시간을 부여받는다. 그들은 이 안에서 자구책으로 하루하루를 연명해나가고 있다.

생계비의 낮은 지출과 예산삭감

난민인권센터는 긴 시간 한국 법무부의 난민예·결산을 모니터링 해왔고, 최근 3-4년 간의 지출들에 심각한 미-지출이 있었다는 것을 발견했다. 이 모든 것은 그들이 “난민이기 때문에” 가능한 일이었다고 생각한다. 2022년 기준 한국의 난민예산은 37억 원이고, 이 가운데 한해 1년 동안 집행된 예산은 약 27억원이었다(전체예산의 74%). 관련하여 최근 4년간의 난민예산의 평균집행률은 69%이다([표-3]).

| Year | Budget Execution Rate |

| 2019 | 98% |

| 2020 | 78% |

| 2021 | 56% |

| 2022 | 74% |

코로나19의 영향으로 2020년부터 2022년까지 지난 3년간의 난민예산 집행은 전반적으로 저조했다. 그나마 2022년은 2021년에 비해 20%가량 높은 예산 집행률을 나타냈지만, 코로나 이전의 평균치를 회복하지 못했다. 난민예산은 ①난민인정심사 ②난민신청자 처우 ③출입국외국인지원센터 ④재정착난민 ⑤연수/회의참석을 1차 분류로 삼고, 이에 근거해 2차 분류와 3차 상세분류로 구조화되어 있다. 이 중에서 가장 낮은 집행률을 나타낸 것은, 난민신청자들의 유일한 권리예산인 ‘처우’항목이었다(35%). 2021년에도 ‘난민신청자의 처우’는 가장 낮은 집행률을 나타낸 바 있다(11.5%).

| Year | Budget | Expenditure | Execution Rate |

| 2020 | 931,497,000 | 575,200,000 | 61.8% |

| 2021 | 931,497,000 | 108,040,000 | 11.6% |

| 2022 | 931,497,000 | 325,171,000 | 35% |

처우예산의 저조한 지출은 처우 예산 중 많은 부분을 차지하는 생계비예산의 미 지출 때문이다([표-5]참고). 코로나로 인해 신청이 감소했다면, 다른 방법을 마련해서라도 어려움을 겪고 있는 난민신청자들을 돌보았어야 한다고 생각한다. 여러 어려움들을 감안하더라도 이와 같은 지출상황은 명백히 비합리적 행정이자 업무실책이라 판단된다.

| Year | Budget | Expenditure | Execution Rate |

| 2020 | 839,362,000 | 546,000,000 | 65.0% |

| 2021 | 839,362,000 | 52,000,000 | 6.2% |

| 2022 | 839,362,000 | 247,186,000 | 29.4% |

| 2023 | 710,120,000 | in progress | in progress |

국민보호의 인종주의

한국사회의 반 난민세력을 특정 하는 것은 매우 어려운 일이다. 그들은 특정 보수단체이기도 하고, 이슬람에 대해 적대적인 기독교이기도 하며, 국가를 보호하기 위해 애쓰는 ‘애국자’이자, 표를 얻기 위한 정치집단이기도 하다. 이들의 다양한 얼굴만큼이나 이해관심 역시 하나로 응축될 수는 없을 것이다. 그럼에도 반 난민세력의 주장은 일정정도의 공통된 기반위에서 형성되었고, 이글은 ‘국민보호’라는 핵심어로 그것을 관찰하고자 한다.

“국민을 보호해야 한다.”

반 난민세력들에게 난민들은 국민들의 생명과 국가안보에 위협이 되는 존재, 즉 테러리스트들로 규정된다. 근거는 가짜뉴스가 재현한 유럽의 풍경들이다. 한국 반 난민세력의 서구중심주의를 관찰할 수 있는 맥락이다. 따라서 이들에게 난민협약과 난민법은 국민의 생명을 해치는 나쁜 법일 뿐이다. 국제법적 규정과 필요성은 국민의 생명을 보호해야 한다는 주장 아래 모두 폐기 된다. 이들의 주장에 따르면, 난민은 박해를 피해 한국에 온 것이 아닌 테러를 저지르기 위해 온 것이 된다. 난민에 대한 악마화의 전형이다. 이제 국민의 생명과 난민권리를 보장하는 일은 제로섬관계에 놓인다. 즉 이들에게 정의로운 국가란 국민의 권리를 우선하고, 생명을 증진하는 일을 해내는 국가이며, 이러한 국가는 곧 난민법을 폐지하고 난민을 내쫓는 국가인 것이다.

난민 문제에 대하여 상대적으로 거리가 먼 대한민국이 이것을 다루는 것에 대해서는 과연 실효성이 있는지가 의문이 듭니다. 또한 현재는 불법체류자와 다른 문화마찰로 인한 사회문제도 여전히 존재합니다. 그렇기 때문에 구태여 난민신청을 받아서 그들의 생계를 지원해주는 것이 자국민의 안전과 제주도의 경제활성화에 기여할 수 있는지 심히 우려와 의문이 드는 바입니다.

이들은 왜 한국에 왔을까요? 예멘은 이슬람원리주의자들인 무포와 남부 알카에다의 분쟁과 함께 일반 시민단체들도 테러를 일삼는 내전 상황입니다. 언론은 말합니다. 이슬람 원리주의자들과 알카에다, 테러리스트는 소수라고. 과연 그럴까요? (중략) 이제 그들은 모두 문을 닫았습니다. 국민의 생명과 안전을 지키기 위해 말입니다. 얼마 전 주변에 아이에스에 가입을 권유한 난민신청자가 구속되었습니다. 제주예멘인들 사이에 칼부림이 일어났으며, 어떤 예멘인은 정신분열증으로 이송되었습니다. 이들이 우리의 안전을 위협하는 사람들이 아닙니까?

제주의 예멘인만 문제되는 것이 아니다. 인천·부산 등 육지로 입국한 예멘인도 217명에 이른다. 이들은 도대체 어디에 있는가. 정부는 이들의 소재를 파악하고 있는지 묻는다. 예멘만 문제가 아니다. 이집트인 난민신청자도 630명에 이르는 것으로 드러났다. 예멘, 이집트 모두 테러조직의 근거지라는 것은 공지의 사실이다. 국민의 불안과 위험을 정부가 외면한다면 국민은 스스로 자신을 지킬 수밖에 없다. 피해자는 결국 평범한 국민이기 때문이다. (중략) 국민들은 지치고 두렵습니다. 개정안으로 국민을 우롱하고 속이지 말고 난민법을 즉각 폐지하시길 바랍니다. 이것이 국민들이 원하는 것입니다. 그래서 여러분과 함께 이렇게 외치고 싶습니다. 우리는 개정이 아닌 폐지를 원한다. 난민법을 즉각 폐지하라. 유럽의 선례가 우리의 미래를 보여줍니다. 독일은 난민법에 상세한 규정을 두었지만 난민범죄가 가장 많이 일어나는 나라 중 하나입니다. 영국과 프랑스는 다문화주의의 실패를 선언했으며, 메르켈 또한 마찬가지였습니다. 아직 늦지 않았습니다. 난민법을 폐지할 것을 다시 촉구합니다.

“무슬림의 폭력으로부터 우리나라 여성들을 보호해야 한다.”

반 난민세력의 국민보호는 보다 구체적으로, 여성에 대한 보호로 재현된다. 이것은 크게 2가지의 이유 때문이다. 먼저, 2018년 당시 한국사회에는 여전히 여성에 대한 폭력이 일상적으로 작동했지만 그에 대한 처벌이나 문제화는 활발히 이뤄지지 않았다. 반면 한국사회가 여성에 대한 폭력을 대대적으로 가시화하고 전체사회의 문제로 설정하는 경우는 그것이 국가의 위기와 연결될 때이다. ‘일본군 위안부’ 문제가 대표적이다. 여성문제가 그 자체, 즉 하나의 독립적인 문제로서 다뤄지지 않고 국가의 문제로 흡수되어 제기되는 구조이다. 다른 하나는 2014년 ‘강남역 여성혐오살인사건’ 이후 한국사회에는 페미니즘에 대한 지지와 반대가 동시다발적으로 커진 바 있는데, 반 난민세력이 사회의 이러한 흐름을 활용했다고도 볼 수 있을 것이다.

유럽의 수많은 나라들이 그들을 받아들여 얼마나 잔혹한 범죄에 노출되고 피해가 희생자가 되었습니까? 피해자는 여성과 아이들이 대부분이었습니다.

아직도 명예살인이 이루어지고 여성을 함부로 여기고 학대하는 이슬람의 여성인권에 대하여 문화적 상대주의라며 온정을 말하십니까? 히잡과 브로카를 착용하지 않은 여성은 강간해도 좋다는 문화를 받아들일 수 있겠습니까?

그들에게는 풍습이 있어요. 건강한 20대, 30대, 40대. 20대는 80프로 이상입니다. 그 사람들이 문화가 어떤건지 알고 있으시죠. 종교도 알고 있으시죠. 여자를 뭐라고 생각합니까. 노예, 성노예, 그리고 그들이 어렸을 때부터 배워온 것, 아버지에게 할아버지에게 배워온 것, 여자는 때려, 성노예 시켜, 알라신을 위하여 목숨을 바쳐! 이런 교육을 받고 있는 사람들입니다.

반 난민세력들의 이와 같은 주장에 영향을 받은 것인지 정확히 확인할 수는 없지만, 당시 복수의 페미니스트 중 일부그룹은 반 난민세력과 유사한 입장을 내놓기도 했다. 반면 온라인플랫폼에서는 난민을 반대하는 입장과 찬성하는 입장을 두고 남성청년들이 논쟁을 벌인 바 있다. 한국의 평화학자 정희진은 이에 대해 다음과 같이 적었다.

“지금 남성 주도의 인터넷 커뮤니티에서는 <한국 여성 보호=난민 반대>와 <난민이 못된 한국 여성을 강간해야=난민 찬성>입장이 싸우고 있다.”

“‘진짜난민’만을 보호해야 한다.”

반 난민세력의 난민반대 주장은 난민 자체를 부정하는 식으로 전개될 수 없었다. 따라서 그들은 반대를 위해 다음과 같이 전제를 바꾼다. “한국에 들어온 난민들은 모두 가짜난민이다.” 이러한 전제만이 국민의 생명과 자신들의 인도주의적 정당성을 함께 보호할 수 있는 유일한 방법이기 때문이다. 이를 위해 온갖 인신공격, 피해자다움의 강요, 도덕적 비난, 나아가 국제법적 지식 등이 동원된다. 대표적인 주장들은 다음과 같다. ①그들은 테러리스트이거나 취업을 위해 온 경제적 이주민이지 진짜난민이 아니다. ②건장한 젊은 남성난민이 어떻게 진짜난민일 수 있나? ③가족들을 고향에 두고 자신들만 피난해온 사람들은 진짜난민일리 없다. ④내전은 난민협약에서 인정하는 난민사유가 아니다.

반 난민세력의 가짜난민에 대한 주장은, 그들이 상상하는 진짜난민의 모습을 어렵지 않게 추정할 수 있게 한다. ①그들은 연약하고 무해해야 한다. ②누가 보더라도 분명한 폭력과 피해를 입은 취약하고 아프고, 가난하고, 위험하지 않은 아동이나 여성, 노인의 모습을 하고 있어야 한다. ③착하고 예의도 발라야 한다(도덕적으로 올바른 모습이어야 한다). ④내전 같은 상황이 아닌 5가지 대표적 난민사유에 꼭 들어맞는 박해를 겪어야 한다. 진짜난민만을 보호하겠다는 주장은 일면 인도주의를 담고 있다.

하지만 이러한 인도주의는 언제든 치안으로 바뀔 수 있다는 점에서 치안 관점만큼이나 위험하고 문제적이다. 불쌍하고 착하고, 위험하지 않아야만 ‘인간대접’을 해주겠다는 건 애초부터 그를 인간으로서 인정하지 않겠다는 것/혹은 언제든 인간다움을 제한시키겠다는 것과 같은 의미이다. 착한 인종주의가 나쁜 인종주의와 맞닿고, 인도주의가 ‘치안’의 다른 이름인 이유다.

지금의 난민신청자들은 가족은 고향에 놔두고 자기 몸만 빠져나왔습니다. 이분들이 난민입니까?

대부분 2-30대의 건장한 남성들입니다. 그들은 스스로 언론인터뷰를 통해 전쟁을 피해왔으며 일을 해 돈을 벌고 싶다고 했습니다. 또한 무리를 지어 대규모로 들어왔으므로 이들은 입국심사과정에서 송환되어야 마땅한 이들입니다. 그러나 정부는 이들을 대한민국으로 입국시켰습니다. 언론과 정부에게 묻습니다. 이들이 난민입니까? 이들은 난민이 아닙니다. 취업목적의 경제적 이주민이며, 정치적 박해를 피해온 난민이 아니라 내전의 피난민입니다. 유엔난민협약을 따를 때에도 이들은 난민이 아니며, 난민법상 난민도 아닙니다. 이를 알고 있으면서도 이들을 입국시키고 이들을 난민이라고 거짓 선전하는 이유는 무엇입니까? (중략) 국민들의 생명과 안전, 행복을 누릴 권리가 파괴되고 있습니다. 불안해 잠을 이루지 못하는 국민들이 늘어나고 있습니다. 우리는 정치적 박해를 받는 진정한 난민을 거부하는 것이 아닙니다. 브로커와 결탁하고 취업을 위해 난민신청 후 받는 지원금을 위해 체류의 수단으로 난민신청을 하는 가짜난민을 우리는 결코 수용할 수 없는 것입니다. (중략) 지금 언론은 국민의 목소리를 반영하고 있지 않습니다. 중립을 지키지 않고 가짜난민을 진짜난민이라고 거짓말을 합니다. 언론은 감성에 빠져있지만 우리는 깨어 진실을 말해야 합니다.

“우리의 이익을 보호해야 한다”: 기독교의 선교경쟁과 정치세력의 난민문제 정치화

반 난민세력의 핵심 구성원들 가운데 빼놓을 수 없는 집단은 기독교와 정치인들이다. 이들의 공통점 중 하나는 국민보호의 외피를 두른 채 자신들의 이익을 주장하고 있는 점이다. 즉 난민들로부터의 국민보호를 앞세우며 기독교는 교세확장을, 정치는 득표와 지지율을 올리고자 하는 것이다.

한국의 기독교는 장기간 무슬림에 대한 공포와 선교 관련 경쟁심을 드러내왔고, 이러한 흐름은 2018년 당시 집단적인 난민반대로 표출된 바 있다. 관련하여 한국 기독교에 대한 사회학적 연구들은, 기독교의 호모포비아적 실천을 실추된 사회적 명예와 정당성 확보, 즉 선교와 교세확장 전략으로 파악하고 있다고 말한다. 기독교의 난민반대 역시 이와 같은 맥락 위에서 설명이 가능할 것이다. 난민에 대한 기독교의 인종주의적 태도는 위에서 설명한 인도주의와 치안의 태도를 모두 담고 있다.

현재 난민에 대해선 동정심과 경계심이 공존한다. 성경적 가르침대로 동정심에 무게를 실어야 하겠지만 경계의 시선도 우리가 품어야 한다고 본다. 경계의 시선을 안정적 기조로 표현하고 싶다. 안정적 기조와 인도주의적 정신을 6:4정도의 기준을 갖고 가는 게 좋다고 생각한다.

-소강석 목사(새에덴교회)

재난을 통하여 견고하던 이슬람의 땅이 흔들림으로 무슬림난민들이 주께로 돌아오고 있다. 유럽이 무슬림이민자들의 사회통합에 겪고 있는 어려움이 한국교회에 경각심을 주고 있는 것도 사실이지만, 무슬림난민들의 수용, 통합, 선교는 ···· 교회의 사명이다. 난민들이 늘어날 것이다. ···· 예멘난민들을 제주도로 보내주신 것은 한국교회의 난민수용과 선교역량 강화를 위해 하나님께서 내리신 연습문제요, 예방주사가 아닐까?

-이호택 대표(피난처)

2018년 예멘난민들의 입국과 그에 따른 전체사회의 위험의식은, 난민문제에 대한 정치세력들의 태도 역시 바꾸어 놓았다. 이것을 난민문제의 정치화라고 부를 수 있을 것이다. 2018년 이전까지 이주민문제에 관한한 우파들의 입장은 시혜에 가까웠다. 한국 최초의 이주민 출신 국회의원과 난민법의 발의가 모두 동일한 우파정당에서 나왔다는 것은 이에 대한 중요한 지표이다. 하지만 2018년 이후 한국의 우파는 유럽의 극우들과 같이 난민문제를 하나의 정치 전략으로 활용하기 시작했다. 그렇다면 한국의 중도파는 어떨까? 중도파는 난민문제를 최대한 건드리고 싶지 않아 한다. 난민들의 권리박탈과 고통은 이와 같은 정치지형에서 발생 및 강화되는 것이다. 모든 정치세력은 전체사회의 위험의식을 득표로 연결 짓는 이해집단이기 때문이다. 아래는 2018년 당시 난민법 폐지 및 개악 안을 발의한 국회의원들과 그들의 주요 주장을 정리해 놓은 것이다.

<Place Table 6 here (no caption; for the Korean section only)>

결론: 난민에 대한 인종주의를 줄이기 위한 해결방법

구조적 해결

한국사회의 난민에 대한 인종주의는 97년 이후 장기화 된 경제적 불평등과 성차별의 구조에서 비롯된 국민들의 공포와 불안을 배경으로 한다. 이러한 배경 위에 ①예멘난민들의 입국 초기, 난민인권을 분명하게 옹호하지 못한 정부와 법무부 ②득표와 기회주의에 함몰된 정치세력(우파는 난민반대, 중도파는 침묵) ③반 난민세력과 ④정치세력에게 기생하며 자극주의를 추구하는 언론 등이 공동으로 참여한 합작품이다. 따라서 살인적인 한국사회의 여러 불평등문제들을 해결하는 것이 우선적인 과제라고 생각한다. 하지만 현재 한국사회는 이와 정반대로 가고 있다. 윤석열정권은 집권 초창기부터 노동조합에 대한 노골적인 탄압과 함께 부자감세를 이어갔고, 최근에는 사회적 안전과 약자들을 위한 복지예산을 전면적으로 삭감한 바 있다.

제도적 해결

현재 한국의 국회에는 재 신청자에 대한 적격심사와 권리제한(신청자의 ID카드를 압수하고, 취업을 금지하는 등)을 골자로 하는 난민법 일부개정안이 계류되어 있다. 이것을 저지하는 것이 시급하다. 재신청자는 정상화 되지 않은 난민심사제도의 산물이며, 이들의 생존권을 정부가 임의로 제한하는 것은 인권과 국제법을 위반하는 행위라는 점을 분명히 할 필요가 있다. 나아가 규범이자 실질적인 처벌 및 구제의 법안으로서 차별금지법이 제정되어야 한다. 난민들의 권리를 보장하기 위한 여러 법·규범적 자원들의 연쇄를 확장해나가는 일이 필요할 것이다. 난민인권센터는 짧지 않은 기간 난민법 개악 안에 대한 반대의 실천들을 모아왔다. 이 과정에서 반복적으로 확인한 바는 난민법이 국내 정치변동과 국내의 법적 논리에 크게 종속되어 있다는 점이었다. 따라서 한편에서는 한국사회에 국제법의 규범을 강화하는 실천이 필요하고, 다른 한편에서는 국내 법 내부의 중심주체로서 국민개념을 이주민과 난민 등을 포괄하는 개념으로 확장하는 실천이 요구될 것이다.

교육적 해결

사회의 교육은 다른 사회적 기능들이 정상적으로 작동할 때 그제야 진가를 발휘할 수 있다. 하지만 이러한 조건은 쉽게 만들어지지 않을 것이다. 따라서 난민에 대한 인종주의를 줄여나가기 위해서는 짧지 않은 시간동안 교육에게 많은 기대를 걸어야 할지도 모른다.

교육적 해결을 위해 크게 2가지의 제안을 하고자 한다. 첫째, 시민이 경험한 폭력과 상처를 구조적인 문제로 이해하는 것을 돕는 교육이 필요하다. 한국의 교육은 입시지식에 대한 열기와는 상반되게 시민의 일상으로서 취약성, 상처, 손상, 아픔, 빈곤 등을 해석하는 지식·교과생산에는 큰 열의를 보이고 있지 않다. 난민에 대한 차별뿐 아니라 사회 전반의 폭력성, 이질적인 것을 견디지 못하는 문화를 극복하기 위해 이와 같은 지식교과를 공교육 내에서 다루는 일은 매우 시급한 교육적 과제일 것이다.

둘째, 민주시민교육의 활성화가 필요하다. 윤석열정부의 지속적인 가치폄하와 공격에도 민주시민교육은 윤리나 일반사회 등의 과목들에서 분화된 교과로 자리잡아가고 있다. 하지만 한국의 민주시민교육은 ①국민·도덕교육과 ②지구화시대의 시민교육이라는 2가지 갈림길 위에 서있다. 지구화시대의 시민교육은 지구화시대의 정의(Justice)를 기준으로 구성되어야 한다. 이와 같은 정의(Justice)는 국민과 시민의 동일성(국민=시민)을 문제화하고, 일국적 차원을 넘어서는 폭력과 평화의 문제를 실천주제로 끌어안는다. 한국의 민주시민교육이 국민·도덕교육으로 기울지 않기 위해서는 지구적 정의의 차원들을 교육적으로 주제화 하는 공교육 안과 밖의 노력들이 필요할 것이다. 난민인권은 이에 대한 더할 나위 없이 좋은 교육의 내용이자 교육목적이 될 수 있다. 내년부터 난민인권센터도 청소년 대상의 난민인권교육팀의 운영을 통해 지구적 정의의 실천으로서 민주시민교육을 만들어가고자 한다. 한국의 교육자들이 이 부분을 사명으로서 감당해주기를 바랄 뿐이다.

Introduction

Racist discrimination against refugees in South Korean society has become prevalent since the arrival of over five hundred Yemeni refugees on Jeju Island in 2018. This response was a major change. There was no such collective opposition to refugees in the early 1990s or in 2013 when South Korea officially announced its commitment to protecting refugee rights to the international community. While prejudice and discrimination against refugees had existed along with xenophobia before 2018, refugees were neither considered a danger nor seen as affecting the whole society. The landscape changed in May 2018, however. Seven hundred thousand citizens signed a petition opposing the guarantee of refugee rights. This was followed by the heated collective denial of the existence and rights of refugees, which continued into the latter half of 2018.1

While the post-COVID-19 era has not seen the same level of collective opposition to and discrimination against refugees, there remains institutional exclusion and discriminatory practices. Some of the recent notable cases include refugee exclusion from COVID-19 relief subsidies and creating an “asylum path without refugee recognition,” in which Afghan refugees were treated as “special contributors.” While the former example highlights the clear discrimination against refugees in South Korea even during times of global crisis, the latter demonstrates a more nuanced form of discrimination. This form of discrimination considers a person’s competence and ability to contribute to the country a prerequisite condition for granting asylum. The latter is problematic because it presupposes hierarchization within refugees.

This essay discusses racism by two groups leading discriminations against refugees: the South Korean government and anti-refugee groups. By “leading discriminations,” I mean to suggest that these groups 1) play a leading role in producing knowledge and problems that are discriminatory and 2) give points of references and legitimacy as a basis for discrimination as a knowledge structure. Racism against refugees also refers to acts of violence committed against refugees as well as tolerated and unquestioned by the society, solely because they are refugees. In this context, I define government racism as institutional racism and anti-refugee groups’ racism as a form of “citizen-protecting” racism. These two forms of racism involve institutions and the concept of “protecting citizens” in their respective values and methods of operation. In other words, protecting South Korean citizens equals protecting the values only important to the citizens.

Institutional Racism

Background: Problems of the 1951 Refugee Convention and Refugee Act

By joining the Refugee Convention (also known as the Geneva Convention), South Korea established its refugee protection system in the early 1990s. However, this was not a well-thought-out approach so much as an instrumentalization for increasing the country’s visibility on the international stage (the move to which was referred to as the “global standard” by the South Korean government). This meant that the government had not established a comprehensive plan for the specific protection of refugee rights. The most basic elements of refugee recognition procedures such as expediency, transparency, and fairness were not institutionalized. More problems began to surface including the systemic failure to protect asylum seekers and asylees’ livelihoods and welfare. The biggest issue, however, was that the refugee status determination procedures were conducted under the Immigration Act. Its limitation was clear: Immigration control may always already supersede refugee rights. In other words, from a legal topological view, domestic law had priority over international law, reducing or limiting its influence and implementation. While the 2013 Refugee Act of South Korea has become an independent human rights law, its implementation did not address these limitations and problems.

During the drafting and legislation process of the 2013 Refugee Act, South Korean civil society pointed to several major issues including 1) Provisions regarding applications filed at ports of entry and departure (Refugee Act Article 6); 2) Provisions regarding simplification and/or omission of screening procedures (Refugee Act Article 8, Paragraph 5); and 3) Lack of provisions regarding treatment of humanitarian sojourners and refugee applicants (Refugee Act Articles 39~44).

Just as activists had feared, the implementation of the Refugee Act did not work. First, the simplified screening at the ports of entry, originally intended to prevent administrative abuse by officials, turned into a de facto refugee status determination interview. As a result, refugees were denied the opportunity for a proper interview. Airport refugees are the product of this system. Second, while the South Korean government increased the number of permissions for humanitarian sojourn following the cases of Syrian refugees in 2014, it was done without guaranteeing the sojourners different job opportunities or basic living security. Consequently, many humanitarian sojourners had to fend for themselves.

To address these issues, several amendment bills have been proposed since 2015. These include plans to improve the port of entry and departure system, to strengthen the protection of applicants’ rights during the refugee status determination procedures, and to treat the sojourners more humanely. However, these plans were never passed, as the justification for legislating the Act on Counterterrorism for the Protection of Citizens and Public Safety in 2015 considered refugees as a threat to national security.

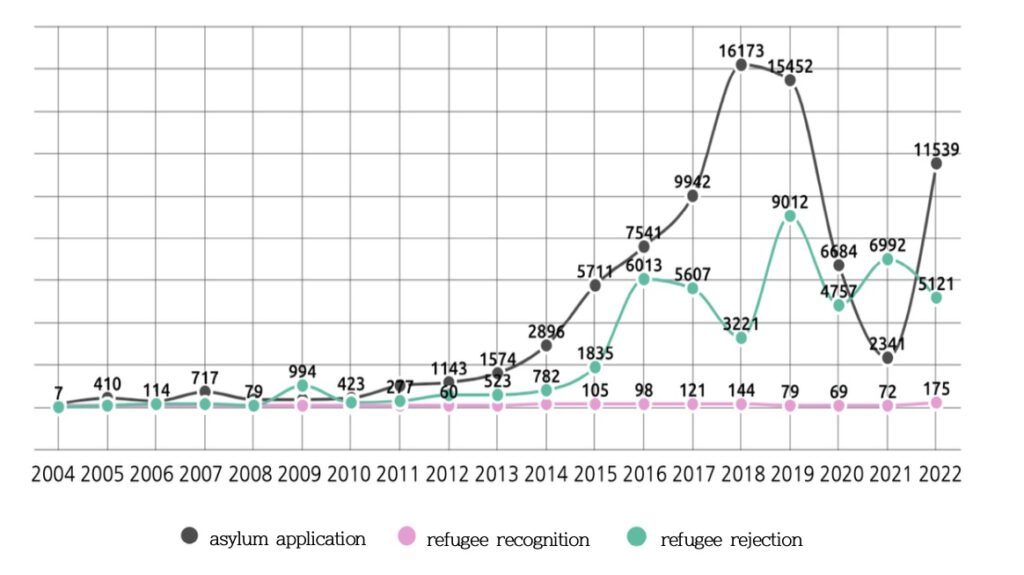

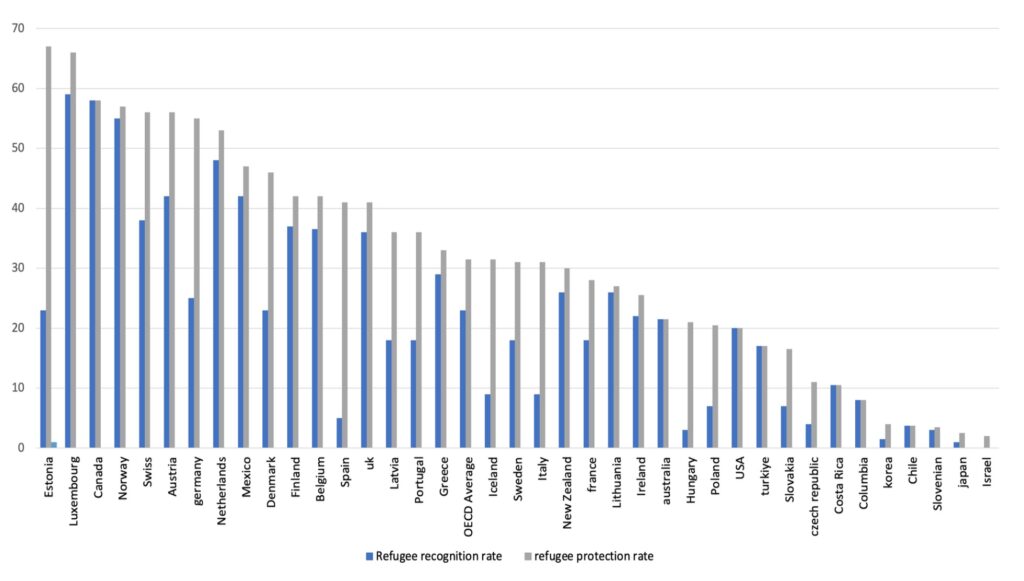

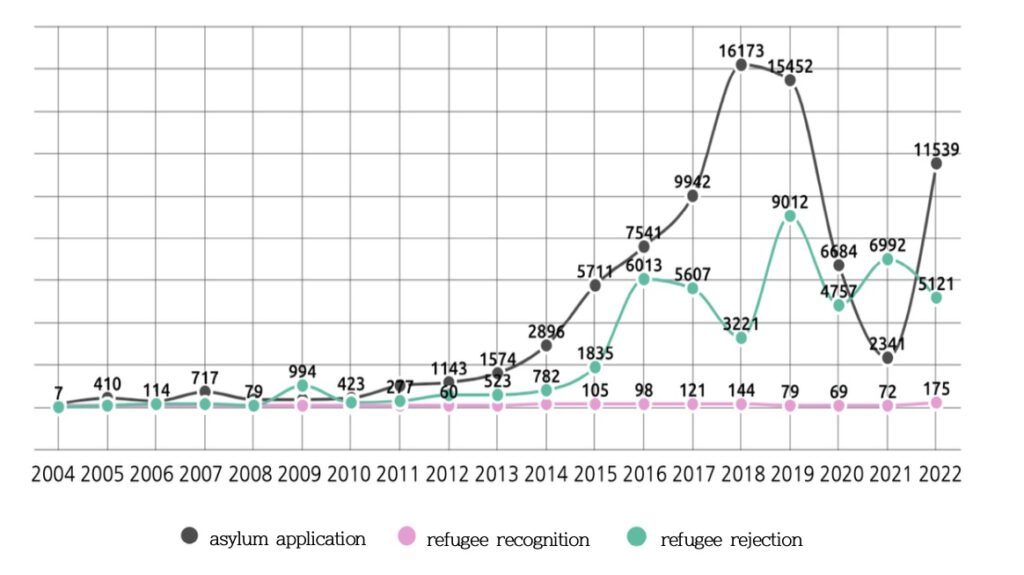

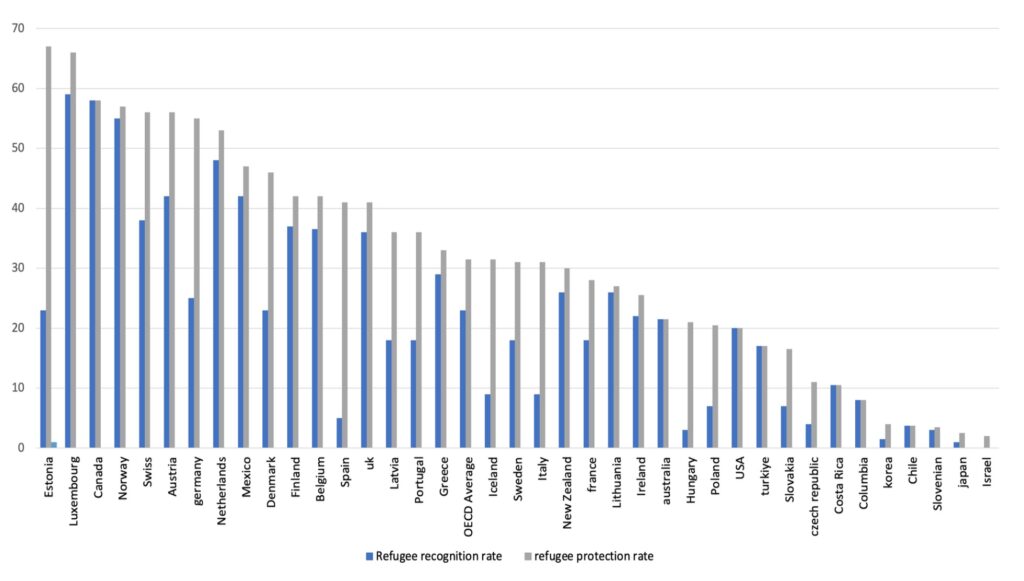

Low Recognition Rate

The low rate of refugee recognition in South Korea indicates that the government’s approach to border control imposes significant limitations on rights protected by international law. This problem can be captured more clearly through comparisons with other OECD countries. South Korea, which positions itself as a developed country, justifies its low recognition rate by portraying refugees as individuals who misuse the system, make false claims about their status, and lie about their situation. However, what has brought refugees to South Korea is precisely South Korea’s promise to the global community. The low recognition rate, as Figures 1 and 2 indicate, clearly shows that the government is not keeping its promise.2

Unstable Refugee Status Determination System

The South Korean refugee status determination system is still unstable. The backlog is very large and the ratio of the applicants to the officials in charge is extremely unbalanced. Cases of procedural injustice continue to occur. The South Korean government has made efforts to decrease the backlog. However, instead of expanding and stabilizing the terms of the determination system, the government has simply tried to hasten the process by creating the “expedited review category,” which is meant to screen the applications that can be rejected more quickly. Its classification criteria have serious issues of inconsistency: They fail to distinguish internationally justifiable asylum applications from the ones that are resubmitted over and over again despite the fact that they are rejected based on the eligibility requirements.

Therefore, the government’s resolution to the backlog issue, which was an expedited process, has actually resulted in even more reapplicants, so much so that there was a case of multiple falsified refugee interview records within the Ministry of Justice, which was a clear violation of human rights. The National Human Rights Commission of Korea and NANCEN estimate that there are between one thousand and two thousand cases of record fabrication.

Airport Refugees, Humanitarian Sojourners, and Reapplicants

South Korea’s unstable refugee system has created airport refugees who are denied the right to apply for refugee status by the government; humanitarian sojourners whose status is uncertain due to the South Korean government’s strategy of bypassing the recognition of refugee status; and reapplicants, who are a clear indication that the government is not willing to protect them. There is no comprehensive long-term welfare plan for these individuals. In this situation where there is no clear policy, refugees who have not been granted asylum are given a waiting period instead of welfare. This waiting period can end suddenly and without warning. During this period of uncertainty, individuals must live on their own on a day-to-day basis.

Insufficient Subsidies and Budget Cuts

According to NANCEN’s monitoring of the Ministry of Justice’s refugee budget and settlement, the budget has been significantly underutilized in the past three to four fiscal years. I believe this is all because the budget is for “refugees.”3 As of 2022, South Korea’s budget for refugees is 3.8 billion won (approximately 2.9 million US dollars), of which 2.8 billion won (approximately 2.1 million US dollars) was expended in that fiscal year. As seen in Table 1, it was 74% of the total budget. The average execution rate of the refugee budget over the past four years is only 69%.

| Year | Budget Execution Rate |

| 2019 | 98% |

| 2020 | 78% |

| 2021 | 56% |

| 2022 | 74% |

Due to the pandemic, the execution of the refugee budget has been generally poor for the past three years, from 2020 to 2022. While the budget execution rate in 2022 was about 20% higher than in 2021, the number is nowhere close to the pre-pandemic average. The budget for refugees is primarily divided into five main sections: refugee status determination procedures, subsidies for refugee applicants, Immigration Reception Center, refugee resettlement, and training and conference attendance. These five sections are then subdivided into smaller, more detailed categories. Among these, the section with the lowest execution rate (35%) is the “subsidies for refugee applicants” section specifically designed to protect the refugee rights. The execution rate for the same budget was also the lowest (11.5%) in 2021.

| Year | Budget | Expenditure | Execution Rate |

| 2020 | 931,497,000 | 575,200,000 | 61.8% |

| 2021 | 931,497,000 | 108,040,000 | 11.6% |

| 2022 | 931,497,000 | 325,171,000 | 35% |

The reason for this underspending relates to the underspending of the aid budget for sustenance, which makes up a significant portion of the subsidies budget, seen in Table 3. If the number of subsidy applications decreased during the pandemic, the government should have taken proactive steps to support the applicants facing difficulties. Given various challenges, this underspending is a result of administrative failures and inadequacies.

| Year | Budget | Expenditure | Execution Rate |

| 2020 | 839,362,000 | 546,000,000 | 65.0% |

| 2021 | 839,362,000 | 52,000,000 | 6.2% |

| 2022 | 839,362,000 | 247,186,000 | 29.4% |

| 2023 | 710,120,000 | in progress | in progress |

“Citizen-Protecting” Racism

It is rather challenging to clearly identify the anti-refugee forces in South Korea. They range from conservative groups, anti-Islam Christian groups, self-proclaimed “patriots” wanting to protect the country, or political parties aiming to secure votes. Their interests are as diverse as their appearance. Nevertheless, their anti-refugee arguments are, to some extent, still formed on a common ground: the idea of “protecting Korean citizens.” This section discusses various aspects related to this idea, in which I include various quotes from anti-refugee rally speeches and statements I collected in 2018.

“The citizens must be protected”

Anti-refugee forces define refugees as terrorists who pose a threat to citizens’ lives and national security, primarily based on disinformation about Europe. This is where we see how Korean anti-refugee forces have become Western-centric. For them, the Refugee Convention and the Refugee Act are harmful to citizens. They dismiss international legal regulations and their necessity, claiming that protecting citizens takes priority. According to anti-refugee groups, refugees come to South Korea not to escape persecution but to commit terrorism. It is a common way to demonize refugees. They see the protection of citizens’ lives and the guarantee of refugee rights as a zero-sum game. For them, a just country should prioritize its citizens’ rights and values of their lives, which justifies repealing the Refugee Act and removing refugees from its borders. On the National Petition of South Korea website and on YouTube, comments claimed,

I am not sure if South Korea can effectively handle the refugee issue since it’s less relevant to the country. In addition, there still are social problems caused by illegal immigrants and cultural differences. That is why I have serious concerns and doubts about whether accepting refugee applications and supporting refugees have anything to contribute to safety of Korean nationals and economic revitalization of Jeju Island.4

Why are they here? Yemen is amid a civil war. Islamic fundamentalists, Al-Qaeda, and even regular NGOs are carrying out terrorist attacks. The media says Islamic fundamentalists, Al-Qaeda, and terrorists are a minority. Is that really true? Now they are all closed to protect the lives and safety of the citizens. Just the other day, the authorities arrested a refugee applicant who had been recruiting IS members among those around him. There was a stabbing incident involving Yemenis in Jeju. One Yemeni was sent to a hospital for schizophrenia. Aren’t these the ones who are threatening our safety?5

The problem is not limited to Yemenis in Jeju. As many as 217 Yemenis arrived on the mainland through ports of Incheon and Busan. Where are these people now? I ask whether the government knows where they are. Yemen is not the only issue. There are as many as 630 Egyptian refugee applicants. It is a well-known fact that both Yemen and Egypt are home to terrorist organizations. If the government ignores the citizens’ anxiety and the danger they think they are in, the citizens are left to protect themselves. The victims here are the ordinary citizens, who are exhausted and scared. Stop fooling and deceiving us with amendments. Repeal the Refugee Act immediately. That is what citizens want. I want us to raise our voice together and say: We want repeal, not amendment! Repeal the Refugee Act immediately! Europe’s precedents provide insights into our future. While Germany has detailed provisions in its refugee law, it has one of the highest rates of crimes committed by refugees. The UK and France have declared that multiculturalism has failed, and so did Angela Merkel. It is not too late. I urgently call for the repeal of the Refugee Act.6

“We must protect our women from Muslim violence”

Anti-refugee groups’ claim to protect citizens specifically concerns protecting women. This is largely due to two reasons. First, while everyday violence against women was still prevalent in 2018, there was no active punishment or acknowledgment of the problem. On the other hand, the only time when South Korea does make violence against women exceptionally visible as a general social problem, it is when it is related to a national crisis. The issue of Japanese military “comfort women” is a perfect example. It is a structure which does not treat women’s issues as stand-alone, but instead as part of the nationalist agenda. Another case in point is the simultaneous surge in both support for and opposition to feminism following the misogynistic “Gangnam Station Murder” case in 2016, which was exploited by anti-refugee groups to support their cause. At the anti-refugee protests and on YouTube channels, participants claimed,

How many European countries open to refugees have victimized their citizens to atrocious crimes? Most of the victims were women and children.7

How can you still speak of embracing cultural relativism, when women’s human rights are violated in Islam through honor killings, maltreatment, and abuse? Can you endorse a culture that thinks it is acceptable to rape women who do not wear hijab or broka [sic]?8

They have customs. [Refugees are] healthy people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. People in their 20s make up over 80 percent. You know what their culture is like, don’t you? You know what their religion is, right? What do they think of women? Slaves, sex slaves. And what have they learned since childhood? What have they learned from their fathers and grandfathers? Beat women up, make them sex slaves, and sacrifice your life for Allah. This type of education is what those individuals receive.9

Although it is difficult to verify how much impact these claims have made, some South Korean feminist groups shared similar views at the time.10 At the same time, young male online users debated on social media platforms whether to reject or accept refugees regarding their positions on women. Feminist peace studies scholar Jung Hee-jin described, “The male dominant internet community shows a clash between the anti-refugee position of ‘protecting Korean women’ and the pro-refugee position of calling for ‘misbehaving Korean women to be raped by refugees.’”11

“Only ‘real’ refugees should be protected”

However, anti-refugee groups’ claims could not necessarily deny the existence of refugees themselves. As a result, they also revised their argument to make sense of their anti-refugee sentiment: “All refugees arriving in South Korea are fake.” They consider this the only way to justify the legitimacy of their “humanitarian” cause with the pretense of protecting the lives of the citizens. To support this premise, they use ad hominem attacks, stereotypes of victimhood, moral condemnation, and their knowledge of international law. In general, they argue 1) They are either terrorists or labor migrants whose actual purpose is to find work; 2) Healthy young men must not be real refugees; 3) Real refugees must not have left their families behind and escaped on their own; and 4) Civil war is not a good enough reason for granting asylum and is not recognized by the Refugee Convention. Figures 3 and 4, screenshots of texts sent during the refugee rights protest in August 2018 to a refugee activist working with NANCEN (Refugee Rights Organization) contain racist, Islamophobic hate speech.

Anti-refugee groups’ claims clearly illustrate what they believe real refugees should look like: They should be weak and harmless. They should clearly appear as sick, poor, and vulnerable victims of obvious violence, especially as children, women, or elderly people.12 They should be nice and respectful; in other words, they should be morally upright. They must have experienced persecution that meets the five fundamental criteria for refugee status not including civil wars. Such anti-refugee groups’ claims are believed to be “humanitarian,” because they claim to protect real refugees no matter what.

However, this claim to humanitarianism is as dangerous and problematic as the security discourse since it can always turn into a discourse about policing for security at any given moment. More specifically, this means that humanity is given only when refugees are nice, pitiable, non-threatening, denying their humanity from the start and limiting their humanity at any moment. This is why anti-refugee groups’ claim to “good racism” is contiguous to “bad racism” and “humanitarianism” is synonymous with “policing.” Anti-refugee protests and YouTube channels have claimed the following:

Current refugee applicants came alone leaving their families behind. How are they refugees?13

They are mostly fit and strong men in their 20s and 30s. They said in media interviews that they fled wars, that they want to work and earn money. They arrived in large groups and should have been repatriated during the immigration process. However, the government allowed them to enter South Korea. I ask the media and the government. How are these people refugees? They are not. They are labor migrants seeking to find jobs. They are not fleeing from political persecution but from civil wars. They are recognized neither by the UN Refugee Convention nor by the Refugee Act. Despite knowing all of this, why did you let them in and spread misinformation that they were refugees? Citizens’ rights to life, safety, and happiness are being destroyed. An increasing number of people are losing sleep because they are scared. We are not rejecting real refugees who are fleeing political persecution. It’s just that we can never accept fake refugees who collude with brokers and apply for refugee status to gain employment and subsidies. The media fails to accurately convey the voice of the people. They have abandoned objectivity and lied about fake refugees being real. We should wake up to tell the truth while the media is drowning in its sentimentality.14

“We must protect our interests”: Christian Evangelism and Politicization of Refugee Issues

Church groups and politicians are among the key players of anti-refugee forces. What they have in common is that they advocate their interests under the guise of protecting citizens. In other words, church groups try to broaden their influence while politicians try to secure votes and increased approval ratings.

For a long time, Christianity in South Korea has been hostile to Muslims and considered them missionary rivals, which imploded into anti-refugee actions in 2018. Sociological studies on Korean Christianity help us contextualize this phenomenon. Church groups have used homophobic practices as a strategy for missionary works and expansion of their influence, which will help them regain social honor and legitimacy for failing Korean Christianity. Church groups’ anti-refugee sentiment can be understood in the same vein. More specifically, their anti-refugee racism incorporates both the humanitarian and policing approaches I discussed earlier. For instance,

Currently, sympathy and vigilance coexist for refugees. While we should have more sympathy following the biblical teachings, we should also be vigilant. To be vigilant means to value stability. It’s preferable to maintain a balance between the desire for stability and the humanitarian spirit, aiming for a 6:4 ratio.15

Muslim refugees are returning to the Lord as the once solid land of Islam is shaken by disaster. The challenges Europe has been facing in integrating Muslim immigrants are worrisome to Korean churches. Nevertheless, it is the church’s mission to accept, integrate, and evangelize Muslim refugees. The number of refugees will rise. Isn’t sending Yemeni refugees to Jeju Island God’s plan to test us, prepare us to accept refugees and strengthen our capacity to evangelize?16

The collective sense of danger spreading across the entire Korean society following the entry of Yemeni refugees in 2018 has also changed political stances. I call this politicization of refugee issues. Until 2018, the conservative right-wing stance on migration was largely patronizing benevolence. This was clearly demonstrated by the fact that the first migrant legislator and the first proposal to a refugee bill both originated from the same conservative right-wing party. Since 2018, however, the South Korean right wing has exploited refugee issues as a political strategy like the European far-right. South Korean centrists, in comparison, prefer not to address refugee issues as much as possible. Therefore, the deprivation of refugee rights and the suffering experienced by refugees are produced and intensified in this political landscape, because all political parties and organizations are interest groups prepared to exploit public concern to secure votes. A number of conservative right-wing legislators proposed the repeal and retrogressive revision of the Refugee Act. Here, I introduce some of their main arguments.

Cho Kyong-tae proposed to repeal the Refugee Act and to excise every provision that includes the term “refugee” from the laws such as the Medical Benefit Act, the Framework Act on Treatment of Foreigners Residing in the Republic of Korea, the Immigration Act, and the Administrative Procedures Act, stating that the goal is to resolve the social conflict surrounding refugee recognition by repealing the Refugee Act. Kim Jin-tae proposed to only allow applications at the South Korean embassies, consulates, and diplomatic offices abroad and to permit entry to verified refugees only. He proposed to remove all definitions of humanitarian sojourners and refugees seeking resettlement, while calling for redefinition of refugees as those specifically recognized as refugees after the screening process. If there is a valid reason for an individual to be suspended or excluded from the screening process, they should be deported since the Refugee Convention does not exist to protect refugee applicants. Kang Seokho proposed a pre-screening process, in which the first-round review should be done within three months and the following appeals review is also done in three months. He argued that, the pre-screening process is meant to improve the fairness and efficiency of the refugee status determination process by expediting the review process and withdrawing applications if an applicant exhibits behavior that is inconsistent with their application. Lee Un-ju proposed welfare cuts for recognized refugees and removal of provisions for living expenses and education for refugee applicants. She also proposed an expedited process of conducting the initial review within two months and the appeals review also within two months, which requires refugee applicants to be housed in designated facilities under the supervision of the Minister of Justice until a final decision is reached. She claimed that the extended review period and unrestricted movement prior to the final decision raise the risk of illegal stay and criminal activities. Countermeasures are necessary. Song Seog-jun also proposed an expedited process of a three-month initial review and a three-month appeals review. Ham Jin-gyu proposed to cut the ninety-day time limit for filing an administrative lawsuit to sixty days, while also proposing that applicants who filed appeals should have only thirty days. Finally, Yoo Minbong proposed to restrict refugee applicants to a designated area of soujourn within the government’s jurisdiction. If an applicant violates this term, they may be imprisoned up to one year or charged a fine of up to ten million won (approximately ten thousand US dollars). Yoo maintained that it will be challenging to control refugee applicants if they are allowed to move around freely, which will increase illegal stays and criminal activities.

Conclusion: How to Combat Racism Against Refugees

Structural Solutions

Anti-refugee racism in South Korea stems from the public fear and anxiety shaped by long-term gender discrimination and economic inequality since the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. It is also a collaboration between multiple actors, including the government and the Ministry of Justice, which failed to unequivocally defend refugee rights during the arrivals of Yemeni refugees, opportunistic politicians preoccupied with votes (primarily the anti-refugee right-wing and the silent centrist), anti-refugee groups, and the media, which appropriated political discourses to profit from sensationalism. While refugee activists’ top priority is to eliminate extreme inequality, South Korea is unfortunately moving in the opposite direction. Since the beginning of the Yoon Suk Yeol administration (2022– ), we have been seeing suppression of trade unions, deep tax cuts for the rich, and most recently, sweeping cuts to social safety nets and welfare budgets for the less privileged.

Institutional Solutions

At present, a proposed amendment to the Refugee Act is under consideration in the National Assembly, which seeks to introduce eligibility reviews for reapplicants and impose certain restrictions on their rights including confiscation of a reapplicant’s ID and an employment ban. It is urgent and important that activists must block this proposal. We must make clear that reapplicants are a result of an inadequate review system and that the government’s arbitrary restriction on their rights to survival is a violation of human rights and international law. This also calls for the passing of the comprehensive anti-discrimination bill, which has been tabled and under consideration for over a decade, for improving ways to provide remedies and enforce appropriate penalties where necessary. This requires enriching the network of legal as well as everyday resources for the refugee rights. The organization I’m part of called NANCEN has been accumulating information and practices for some time against the retrogressive amendment of the Refugee Act. In the process, we have repeatedly witnessed that the effectiveness of the Refugee Act relies heavily on shifts in domestic politics and the judicial logic. Therefore, on the one hand, it is necessary to emphasize on the importance of international law in South Korea; on the other hand, it is also necessary to broaden the concept of citizenship within domestic law to include migrants and refugees.

Educational Solutions

Education can only be effective when all other social institutions operate properly. However, this is also not as easy as it sounds. This means that we may need to place a significant, long-term emphasis on education, hoping to eliminate anti-refugee racism.

To that end, I want us to consider two things. First, we need education that helps citizens understand violence and trauma as structural problems. South Korean education, while invested solely in college placement exam preparations, has not placed as much importance on producing knowledge and curriculum that help us understand how vulnerability, injuries, harm, pain, and poverty are part of our everyday lives. I believe that this is an urgent task for public education, which must help us change the culture where South Korea is becoming more violent and more intolerant towards diversity and inclusion, including for refugees.

Second, we need to strengthen curriculum on democratic citizenship. Despite the current administration’s undermining of and attacks on democratic citizenship, it is nevertheless becoming a distinct and important subject separate from the general curriculum on ethics and social studies. Educating democratic citizens in South Korea is now at the crossroads of whether to prioritize national and moral education over citizenship education in the global era. Citizenship education in the global era must reflect on the principles of global social justice. Global social justice challenges the ways in which citizenship is limited to nationality, incorporating transnational issues of violence and peace as important praxis. To ensure that democratic citizenship education does not lean toward national and moral education, it is important to build the curriculum based on a wide range of subjects related to global social justice. Learning about refugee rights are great teaching objectives and can be perfect for global social justice curriculum building. In 2024, NANCEN will run an outreach team specializing in refugee rights education, which serves youth groups by promoting democratic citizenship education to practice global social justice. It is my wish to see more South Korean educators embrace this task as their important mission.

Notes

- Leading up to the anti-refugee movement in May 2018, a series of national candlelight rallies had taken place beginning in the second half of 2016, protesting political corruption and demanding the impeachment of then-president Park Geun-hye. The last rally took place in April 2017, when there was a clear prospect of regime change by candidate Moon Jae-in. The concept that defined the mindset, perceptions, and actions of South Koreans during this period was national sovereignty. Every speech at every rally cited Article 1 Paragraph 2 of the Constitution: “The sovereignty of the Republic of Korea shall reside in the people, and all state authority shall emanate from the people.” The emphasis on the nation fostered a strong sense of unity among the people, eventually leading to the impeachment of Park Geun-hye. The emphasis on the nation was repeated in May 2018, which shared the energy and anticipation experienced from the impeachment protests. National sovereignty was understood as prioritizing the interests of nationals. Many South Koreans have adopted this belief as a framework for their thinking and perception, leading to the practice of collective self-protection and exclusion of others. That is what I call “post-May 2018 racism against refugees,” which I discuss throughout. Therefore, racism against refugees takes a form of collective defense mechanism by those who protested Park Geun-hye but felt that they were not respected as the members of the nation (especially in terms of their socioeconomic status or representations of gender) under the new presidential administration. Racism against refugees may also be understood as South Koreans’ retaliation against the government based on their mistrust and frustrated expectations. In fact, the anti-refugee group-led rallies have time and again featured the anti-government rhetoric deploring the government for abandoning its people, and that South Koreans must protect themselves. According to the UNHCR’s 2021 refugee perception survey, the Korean respondents showed that they could be more welcoming towards refugees if they have a greater pride as citizens of a “developed” country as well as stronger trust in the fairness of the judicial system and the South Korean society. ↩

- NANCEN Statistics Institute, “Refugee Status in Korea,” NANCEN Refugee Rights Center, accessed August 6, 2023, https://nancen.org/2344; Jang Young Wook, “Nanmin yuipgwa sahoegyeongjejeok yeonghyanggwa jeongchaek gwaje” (The Socioeconomic Impact of Refugee Influx and Policy Challenge), Global Issue Brief 9 (2023): 34. ↩

- For the refugee related budget and expenditure of the Ministry of Justice, see https://nancen.org/2330 and https://nancen.org/2331, accessed November 9, 2023. ↩

- National Petition of South Korea, https://www1.president.go.kr/petitions/269548, unavailable as of November 2023. ↩

- People’s Action for Prioritizing the Nationals (Formerly Joint Action Against Refugees), “Official Live Broadcast of the Second Anti-Refugee Rally at Gwanghwamun,” Seoul, Korea, streamed live on July 14, 2018, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/live/kVQ0upSKDXY?si=-U7UtLITmoG1r8We, accessed September 27, 2023, unavailable as of November 2023. ↩

- Lee Dae-woong, “Yemen nanmin ‘burinjeong’edo imsi cheryu gyeoljeong, gungmindeul buran haeso jochi isseoya” (Yemeni Refugees “Unrecognized” But Given Permission to Stay Temporarily; Measures to Relieve Public Anxiety Necessary), Christian Today, October 17, 2018, https://www.christiantoday.co.kr/news/316888. ↩

- People’s Action, “Second Anti-Refugee Rally.” ↩

- People’s Action, “Second Anti-Refugee Rally.” ↩

- I Am Peter, “Why They Are Against Yemeni Refugees,” July 2, 2018, YouTube, https://youtu.be/UnyTeJqn0jE?si=p1ttSkQOcjM6Ex3f. ↩

- South Korean feminist critique of anti-refugee positions was published in an edited volume titled Feminism Without Borders, whose title cites Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003). Sunhye Kim, et al., Gyeonggye Comneun Peminijeum {Feminism Without Borders} (Seoul: Waon, 2019). ↩

- Jung Hee-jin, “Nanminboda jagungmin anjeon?” (Safety of Korean Nationals over Refugees?), The Kyunghyang Shinmun, July 24, 2018, https://www.khan.co.kr/opinion/column/article/201807242025005#c2b. ↩

- For instance, there was a widespread claim in 2018 that those who wear Nike and use iPhones cannot be refugees. ↩

- I Am Peter, “Why They Are Against Yemeni Refugees.” ↩

- People’s Action, “Second Anti-Refugee Rally.” ↩

- Pastor So Kang-suk of the Sae Eden Presbyterian Church, quoted in Kim Jin-young, “Yemen nanmin satae…‘iseulam’gwa ‘indojuui’saieseo” (Yemeni Refugee Crisis: Between ‘Islam’ and ‘Humanitarianism’), Christian Today, https://www.christiantoday.co.kr/news/314058, accessed Sep 27, 2023. ↩

- Lee Ho-taeg, President of the Refuge pNan: Christian NGO Aiding Refugees, quoted in Lee Ho-taeg, “{Siron} jeju yemennanmin, gyohoeneun eotteoke hal geosinga?” (Yemeni Refugees in Jeju: What Should the Church Do?), Kidok Shinmun, https://www.kidok.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=110170, accessed September 27, 2023. ↩