Filmed and edited by Pafsanias Karathanasis. Research by Pafsanias Karathanasis and Yannis Kallianos.

Introduction

To walk this narrow path, one’s pace must be hesitant, yet confident. Both qualities are necessary for carrying out the balancing act needed to stay safe. This is the narrow underground median strip that separates the two sides of Moustoxidi street, in central Athens. Despite the fact that it can be considered unsafe, this passage is used regularly as many people, especially during the night, consider it safer to cross than the square above.

This observation leads us to the main argument of this paper. Since the pandemic erupted, Protomagias (First of May) Square, which is situated above Moustoxidi street, has transformed into an “affective infrastructure”1 formative of care. During the first lockdown, Protomagias Square began to be swarmed with people.2 Almost instantly, it transformed from a space that was mainly used by local and often marginalized communities, and considered by some unsafe after dark, to one that accommodated numerous people of all ages and of different cultural backgrounds. Soccer, cricket, boxing, walking, running, and other physical activities occupied a major part of the square. The space was also used for discussions, hanging out, drinking in small groups, singing and dancing in semiprivate parties or at impromptu concerts, and even political events like assemblies and discussions. Being one of the few public open spaces in this densely built area of the center that remained accessible during the lockdown, it hosted simultaneously a variety of collective and individual everyday practices. Even though the square is of moderate size, the diverse activities that took place there did not exclude each other, but rather formed a sense of collective everyday togetherness; a way of being in public space that was reconstituted around notions, affects, and practices of care. Eventually, it made possible an essential social and “affective practice”3 of balancing between two harmful situations; between the danger of being infected or infecting others, and the danger of being isolated. It transformed into a safe(r) space where care, which as Gabriela Cabaña, drawing on David Graeber,4 argues is “any labor that is directed at maintaining or enhancing another’s freedom,”5 could be exercised.

In this paper, we approach care as a “social capacity and activity involving the nurturing of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life.”6 Within this context, care has been strongly associated with public space as a way to create a “sharing infrastructure” that advances “mutual support.”7 Such a perspective draws attention to the infrastructural qualities of public space, to the ways in which its materiality, along with its everyday relational and processual dynamics, are interrelated with “the movement or patterning of social form,”8 and thus have the capacity to be co-formative of “how affinities take shape, or not.”9. It also points to the fact that infrastructural materialities, such as public spaces, can “mobilise” affect and “feelings which can be deeply political.”10 Here, we argue that certain forms and modalities of care during the pandemic have been inflected by the material, affective, socio-cultural, and political registers of public space. It is through the different material and emotional manifestations of sociality and solidarity which have emerged in the square that particular forms of care have been made possible. Such a labor of care, as we demonstrate, has not only alleviated the effects of the pandemic and the strict measures which have been imposed to control it, but has also helped people to collectively renegotiate their positioning in the city. Our intervention is based on our own experiences of frequenting the square before and during the pandemic crisis. By choosing to include in our contribution not only photographs, but also a video, we present a perspective that renders more intelligible the visual, acoustic, intimate, and affective forms of everyday care. Following the sensory approach, that is central in current visual ethnography,11 our observational video “travels” through the different places of the square, during day and night, to allow the viewer to get a sense of the space and the unfolding multiple practices of care.

Athenian Public Space in Never-Ending Trouble

The COVID-19 pandemic erupted in Greece during the last days of February 2020. Within a month, very strict measures had already been employed by the Greek government, and they led to the closure of public educational institutions, restaurants, shops, and so on. On March 23, a complete lockdown was imposed that restricted all “non-necessary” movement. This was enforced through strict and extended policing and surveillance that also entailed the obligation to indicate, through SMS or a “movement permit form,” the reason and the details for each movement under threat of high fines. Within the context of this pandemic juncture, public spaces reemerged as critical sites of sociopolitical antagonism. Reenacted in accordance with ideas of “social distancing,” the governance and policing of public spaces have been reconfigured in light of their recasting as potentially contagious places.12The term “social distancing” has been criticized for sustaining and reinforcing existing inequalities and exclusions, as well as for the potentially threatening political consequences that it entails.13 Although such processes further intensify the biopolitical aspect of urban governance and planning, in Athens (the right to) public space has constantly been in trouble and under threat.14 This is evidenced by both past and present urban development and surveillance projects, and by the increasing attempts to privatize and gentrify areas of the city, especially after the Athens 2004 Olympic Games and the eruption of the 2010 economic crisis.15

In Athens and in Greece more generally, the privatization of public space has been strongly associated with the rise of commercial “third spaces” that often occupy large parts of it. According to Setha Low and Alan Smart, “third spaces are commercial establishments such as bars, restaurants, gyms, malls, barbershops, and other places frequented between work and home.”16 Commercial “third spaces” rapidly grew to become mainstream sites for meeting up, socializing, and performing the modern self, thus, in a way, replacing the traditional coffeehouse (kafeneio)—which is an exclusively male space.17

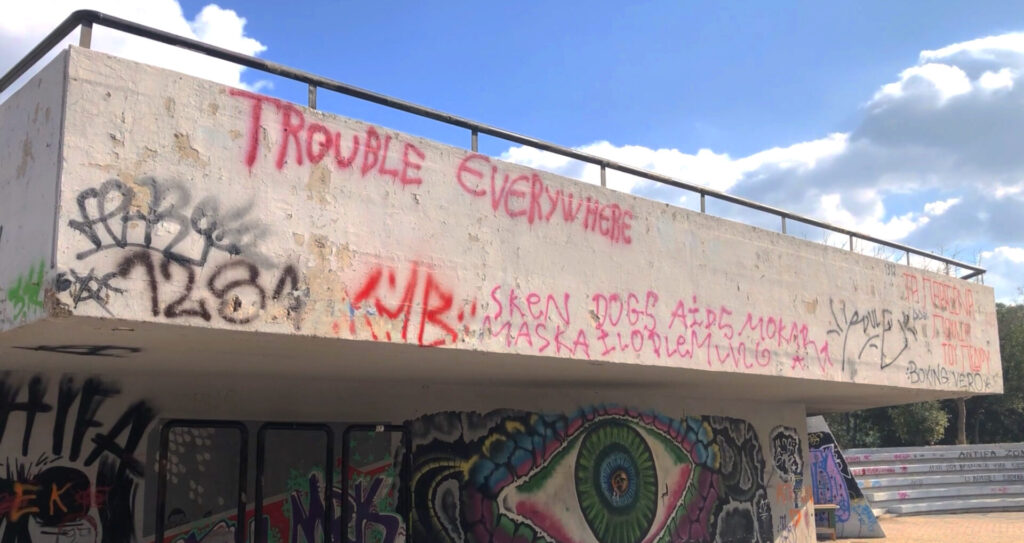

The last two decades have also been marked by important attempts to reclaim public space in the everyday, away from institutionalized politics. Hence, the city has seen the emergence of critical collective practices associated with the right to public space, such as mass demonstrations, occupations, guerrilla gardening, graffiti, and various local and neighbourhood initiatives. This urban legacy has been co-formative of the practices which emerged during the pandemic at the Protomagias Square. Contrary to official and state narratives that impose social distancing, these everyday activities put forward an understanding of public space as an infrastructure of care, through which existing dominant forms and norms of sociality and interaction could be challenged and transformed.

Protomagias Square: A Critical Public Space

Protomagias Square sits between the Pedion tou Areos (PtA), the largest park in central Athens, and the former Evelpidon Military Academy complex, which now includes the main court of justice, the Hellenic National Defence College (HNDC), and a grove (alsos Evelpidon). After its redevelopment in the 1980s, Moustoxidi street was moved underground and Protomagias Square was constructed. In the pre-COVID era, apart from a crossing and a bridge, the square was mainly used by migrants and youth to hang out and play dominoes or cricket, and as an open space for kids to play in. During the first lockdown, Protomagias Square remained as one of the few public open spaces in downtown Athens. The massive increase in the number of people using the square, and thus in recreational, physical, and other activities, is also associated with the shutting down of all “third spaces” and with the temporary closure of the neighbouring park. This change in the square’s use reflects an essential need for social interaction, emotional support, and for being (in and) part of a social public arena during the pandemic. It is within this context that Protomagias was reenacted as an “affective infrastructure” that became a critical point of reference. During this period, it was regularly full of people who used it in a variety of ways. Eventually, during the summer, it became a meeting point for the wider metropolitan center.

To understand the kind of care that public space can engender, we approach Protomagias as a constellation of diverse but co-constitutive socio-spatial and affective forms, relations, and processes. These made possible a kaleidoscope of activities that resulted in the blending of different sounds, movements, smells, and other affective dynamics, thus creating a sense of intimacy and togetherness that permeated collective use of space. This, in turn, produced a public arena through which the anxiety, self-isolation, and uncertainty generated by the pandemic and its management could be confronted.

We identify three main spaces in the square in which such everyday activities take place: First, there is a wide-open area that occupies the largest part of the square. This area is separated between a higher level, situated in front of the HNDC, and a lower level next to a private café and one of the entrances to the park. Over the past years, the higher level has been regularly used by Pakistani and Afghan migrants as a cricket field. The lower level is mainly the site where kids play and ride their bicycles. Moreover, between these two levels there is a small skateboard and bicycle ramp, which is also systematically used by youth.

Second, and towards the southern end of the large open space, sits a Platanus (plane tree) in the middle of a square-built bench. For some years, it has kept a community of Albanian migrants company. They gather under its shade to play dominoes, drink beer, and discuss, thereby creating a self-organized communal space.18 Moreover, this community has assembled a considerable number of upcycled chairs and tables over the course of the years. While, during the day, these are used by the community, at night various other groups and people who frequent the park also use them to gather around to drink, eat, or even celebrate important personal events.19 This Platanus constitutes part of a shared “affective infrastructure” which gives rise to diverse socialities that do not exclude each other, thus becoming formative of critical spatiotemporal arrangements of care during the pandemic.

The third site is a small amphitheatre (theatraki) made out of concrete that is used for a variety of purposes. Apart from being a space of gathering, celebration, or casual discussion, the theatraki has also been used for political assemblies and events. This is also due to the fact that several grassroots political groups and collectives have been deprived of their usual gathering spaces. In this way, the theatraki has been playing an important role in facilitating the continuation of unmediated political grassroots action during the pandemic.

Public Space: A “Matter” of Care

The various everyday collective practices at play in Protomagias Square offer important insights into the ways in which the socio-material and affective dynamics of public space have been shaping forms of care during the pandemic. By providing a place in which to be together, and in which to participate in the production of inclusive and unmediated practices, the square has transformed into a safe(r) space where affective manifestations of interdependence and sociality have helped to collectively (re)negotiate and alleviate everyday fears and anxieties. Care, then, as an everyday practice and capacity to “maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’” towards collective well-being,20 has been woven into fragile socio-spatial and affective forms of being and acting in public space.

Here, we identify at least two main interconnected and interdependent qualities of care inscribed in the square: self-care and care for each other. The first is embodied in the practices that people manifest into caring for themselves. Physical exercise or even just the state of being in public space constitute part of such care. Second, care for each other is evident in the various ways in which parents, friends, dog owners, and those belonging to wider social networks act as caregivers. By regularly maintaining their social ties, and by offering emotional support, they also sustain the well-being of all those who form part of their everyday social networks, neighborhood, and affinities. Such forms of caring have also been enacted via everyday practices of socio-spatial and material repair and maintenance. The mending of chairs, tables, and other shared materialities surrounding Platanus, is an important indication that issues of care “also take shape in the environments we inhabit and move through.”21 Moreover, practices concerning the care for each other are also strongly demonstrated in political practices that challenge authoritarianism, injustice, and everyday exclusions. Assemblies, concerts, and other political events in solidarity with migrants, offer care by imagining and creating inclusive spaces, as well as by actively supporting people in need. They represent an important quality of care as “the expression of solidarity versus charity” that is “mobilized as a response to neglect or catastrophe.”22 These two forms of care point to its capacity to be shared and manifested “according to the demands of the situation.”23

Overall, these public and plural materialities, visibilities, and affective forms of care, which have been generated through public space, have been crucial during the pandemic. They constitute critical “affective care relations” that “co-create others relationally in a non-alienating, non-exploitable way.”24 Crucial is the fact that, throughout the day, one practice was replaced by or overlapped with another, without impeding their reemergence. This helped foster the development of social connections and ties in public space, not by simply not-excluding, but by actively nurturing the “breadth, depth, and textures of sociality” through the production of a communal, public, and shared “social infrastructure”25 Instead of implying a single homogenous community, however, these practices of care signify the emergence of (plural) social and collective potentialities that are shaped, articulated, and manifested around the dynamics of the communal in public space. Here, we draw on Gautam Bhan, Teresa Caldeira, Kelly Gillespie, and AbdouMaliq Simone’s conceptualisation of the collective as “plural and not necessarily agreed upon: it is just shared in its contradictions, ambiguities, multiplicities, and partialities.”26 Practising care in Protomagias Square became part of a need and a demand. This public enactment of care in the square comprises part of an everyday ongoing collective and affective labor of co-curating the balancing act of staying safe between contagion and isolation. Entailed in the conceptualisation of public space as infrastructure of care is the potential for the engendering of alternative and “different ideas of publicness,”27 which in times of social distancing have proven to be ever more crucial.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mattijs van de Port, Andreas Chatzidakis, Saskia Fischer, and Ioanna Manoussaki-Adamopoulou for their very useful suggestions. We are also thankful to the editors of this forum and the anonymous reviewers for providing insightful and constructive comments.

Notes

- Lauren Berlant, “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34, no. 3 (2016): 414, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989. See also Hannah Knox, “Affective Infrastructures and the Political Imagination,” Public Culture 29, no. 2 (2017): 363–84, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-3749105. ↩

- The first lockdown in Greece began on March 23 and lasted until May 4, 2020. While this paper was being written, another national lockdown was imposed on November 7, 2020, which from early May 2021 began to be gradually lifted. ↩

- Margaret Wetherell, Affect and Emotion: A New Social Science Understanding (London: Sage, 2012). ↩

- David Graeber, “The Revolt of the Caring Classes,” Grande conférence, Collège de France, March 22, 2018. ↩

- Gabriela Cabaña, “The Irruption of Care, or Facing a Pandemic in Times of Revolution. Covid-19,” Fieldsights, 2020, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/the-irruption-of-care-or-facing-a-pandemic-in-times-of-revolution. ↩

- The Care Collective (Andreas Chatzidakis, Jamie Hakim, Jo Littler, Catherine Rottenberg, and Lynne Segal), The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence (London: Verso, 2020), 5. ↩

- The Care Collective, The Care Manifesto, 51. ↩

- Lauren Berlant, “The Commons,” 393. ↩

- Angela Mitropoulos, Contract & Contagion: From Biopolitics to Oikonomia (Brooklyn, NY: Minor Compositions, 2012), 116. ↩

- Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 333, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522. ↩

- Phillip Vannini, ed., The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video (London and New York: Routledge, 2020). ↩

- In March 2020, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis stated that “we are at war with an invisible enemy.” Newsroom (2020). “Μητσοτάκης: Είμαστε σε πόλεμο, ο εχθρός δεν είναι ανίκητος,” Kathimerini, March 17, 2020, accessed October 10, 2020, https://www.kathimerini.gr/politics/1069606/mitsotakis-eimaste-se-polemo-o-echthros-den-einai-anikitos. (Accessed 10 October 2020). Such discourses further complicate and problematize the ways in which we position ourselves and we relate to others in public space. ↩

- For a critical analysis of the political ramifications of the term social distancing, see Giorgio Agamben, “Social Distancing,” Autonomies, April 7, 2020, http://autonomies.org/2020/04/giorgio-agamben-social-distancing. ↩

- Here we draw on Papataxiarchis’s understanding of trouble as “a multi-dimensional trope that allows the simultaneous consideration of many different facets—economic, social, political, ideological, mental/psychological—in the production of antagonism.” Evthymios Papataxiarchis, “Pragmatism against Austerity: Greek Society, Politics, and Ethnography in Times of Trouble” in Critical Times in Greece: Anthropological Engagements with the Crisis, edited by Dimitris Dalakoglou and Georgios Agelopoulos (New York: Routledge, 2018), 230. ↩

- The Olympic Games and economic crises have been critical for reshaping cities around the world. For the case of Athens, see Stavros Stavrides, “Athens 2004 Olympics: An Urban State of Exception which Became the Rule” in Mega-Events and the City: Critical Perspectives, edited by Carlos Vainer, Anne Marie Broudehoux, Fernanda Sánchez, and Fabrício Leal de Oliveira (Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital Editora, 2017); Georgia Alexandri, “Planning Gentrification and the ‘Absent’ State in Athens,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42, no 1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12566. ↩

- Setha Low and Alan Smart, “Thoughts about Public Space During Covid-19 Pandemic,” City and Society 32, no. 1 (2020): 1-2, https://doi.org/10.1111/ciso.12260. ↩

- Herzfeld Michael, The Poetics of Manhood. Contest and Identity in a Cretan Mountain Village (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), 52; see also Evthymios Papataxiarchis, “Ο κόσμος του καφενείου. Ταυτότητα και ανταλλαγή στον ανδρικό συμποσιασμό,” in Ταυτότητες και φύλο στη σύγχρονη Ελλάδα: ανθρωπολογικές προσεγγίσεις, edited by Papataxiarchis Evthymios and Paradelis Theodoros (Athens: Kastaniotis Publications, 1992). ↩

- For a visual ethnographic study of this community, see Christina Divari, Dimitra Tsiourva, and Olympia Exarchou, The Domino Effect” (Athens Ethnographic Film Festival, 2015), https://www.ethnofest.gr/film/the-domino-effect. ↩

- Several birthday parties were celebrated during the summer under the Platanus tree, using the same tables and chairs. ↩

- Berenice Fisher and Joan C. Tronto, “Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring” in Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives, edited by Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson (Albany: State University of New York, 1990), 40. ↩

- The Care Collective, The Care Manifesto, 45. ↩

- Hi‘ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart and Tamara Kneese, “Radical Care: Survival Strategies for Uncertain Times,” Social Text 38, no. 1 (2020): 7, https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-7971067. ↩

- Ashraful Alam and Donna Houston, “Rethinking Care as Alternate Infrastructure,” Cities 100, no. 102662 (2020): 7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102662. ↩

- Kathleen Lynch, Manolis Kalaitzake, Margaret Crean, “Care and Affective Relations: Social Justice and Sociology,” The Sociological Review 69, no. 1 (2021): 58, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120952744. ↩

- Alam Latham and Jack Layton, “Social Infrastructure and the Public Life of Cities: Studying Urban Sociality and Public Spaces,” Geography Compass 13, no. 7 (2019): 1, https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12444. ↩

- Gautam Bhan, Teresa Caldeira, Kelly Gillespie, and AbdouMaliq Simone, “The Pandemic, Southern Urbanisms and Collective Life,” Society and Space, December 13, 2020, https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/the-pandemic-southern-urbanisms-and-collective-life. ↩

- Latham and Layton, “Social Infrastructure,” 4. ↩