Much of the rhetoric around racialized discrimination in Israel centers on Israeli Jewish treatment of Palestinians. These divisions between Israeli Jews and Palestinians are often rooted in an imaginary homogenous Israeli Jewish population in opposition to a distinctly “other,” and equally homogenous, Palestinian population read as different racially (Arab), religiously (Muslim, despite a significant Christian population), and culturally (through an Orientalist lens). However, an examination of the experience of Mizrahi1 Jews can be instructive as to the ways that racism and Zionist white supremacy function within Jewish Israeli society—through a hegemonic Israeli Jewish identity rooted in Ashkenazi2 identification and experiences.3 As sociologist Ronit Lentin has demonstrated, Israel’s settler colonialism is implemented in a racialized fashion both with regard to the Palestinians and the non-Ashkenazi/white Jewish populations across Palestine and Israel.4 With this in mind, this article considers the video work Eye and Heart, by Israeli Jewish artist of Yemeni descent Leor Grady, as well as another series of works in his exhibition Natural Worker. These works address the marginalization, erasure, and exile of Yemeni Mizrahi Jews in Israel. In the video work, Grady highlights how, in its absorption into Israeli folk dance, traditional Yemeni dance has been uprooted from its site of origination and “whitewashed.” Considered alongside other works in the exhibition, Grady makes clear how this cultural appropriation fits into a broader Israeli erasure of the Yemeni Jewish history and presence in Israel. While Mizrahi society in Israel has been discussed by scholars such as Yehouda Shenhav, and Mizrahi confrontations with Ashkenazi hegemony in the arts have been discussed in the context of literature and film by scholars such as Ammiel Alcalay, Kfir Cohen, Hannan Hever, Yochai Oppenheimer, and Ella Shohat, this conversation is largely absent from English-language publications on the contemporary fine arts.5 In this article, I argue that Grady’s work demonstrates the contemporary legacy of historical discrimination against and erasure of Yemeni Jews in Israel, and specifically how this discrimination manifests in culture and the arts. Eye and Heart, which features dance, points to the continued impact of early Zionist dance instructors and choreographers who instrumentalized the position of Mizrahi Jews as both Middle Eastern and Jewish to make a connection between the new Israeli cultural identity they were forming, largely from Eastern European immigrants, and the land of historic Palestine. This new Israeli cultural identity whitewashed Middle Eastern cultural elements, from the arts to culinary influences, to help build the image of the new Israeli Jew—an image that always had a white face, even as Israeli demographics reflected a growing Mizrahi majority.6

Eye and Heart is a single-channel video projection about three and a half minutes long that displays two shots of a theater side-by-side (Figure 1).7 Each view includes dancers performing on a black stage in front of black curtains.8 On the left, there are two young men, each dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, all in black. One plays a metal “drum,” a large olive oil tin, creating the beat for the second man’s dance.9 While the percussionist remains standing as the other man dances, the dancer maintains a body positioning mostly turned toward the musician, engaging with him as a partner in the dance. This partnering of dancer and musician is emphasized further by their matching outfits. In contrast, on the right, two different dancers appear on the stage, shirtless, dressed in gold and silver leggings respectively. The two dance together—sometimes physically touching one another, joining hands, other times performing the same moves and steps in unison or complementary moves that respond to each other. The musician, who appears again in the same black clothing, is ignored by the two dancers. The dancers only engage with each other, not the source of their music.

While all three of the dancers are performing movements rooted in Yemeni folk dance, there are distinct differences in how the dances appear. In addition to the engagement, or lack thereof, with the musician, there is a connectedness between the dancer in black and his movements that articulates a genuine knowledge and understanding of the moves he makes, while still exuding an improvisational feel. While he does smile at times, there is a seriousness in his performance—the smile crawls across his face as he looks to the musician, connecting his moves with the percussion. The dancers in silver and gold however, move playfully, smiling, and in some moments almost appearing to laugh. There is a silliness to parts of the dance that portray a distinct lack of seriousness, or at least lack of training in or connection to the specific moves they are performing. They appear to be playing with/at the dance, rather than performing it. The dancers’ differing appearances, beyond just their outfits, hint at the reasons for the contrast in performances.

While the dancer in black has dark skin and black hair, the dancers in silver and gold are light skinned, with lighter brown hair—one of them sporting a “man bun.” The dancer in black, Evyatar Said, is Yemeni, and while not trained as a dancer, he, as Grady puts it, “simply holds his history in his body as a reflection of the [Yemeni] community he grew up in.”10 For the video, Grady asked Said to improvise his dance, and the result is the performance recorded on the left. The dancers on the right in gold and silver on the other hand are professionally trained modern dancers. While one, Matan Daskal, is Ashkenazi, the other, Adi Boutrous, is a Christian Arab, though he has noted that people do not visually “read” him as Arab.11 As such, these dancers appear as visual representations of the hegemonic Ashkenazi culture, in contrast to the Mizrahi Yemeni one represented by Said. Additionally, as “modern” dancers, they embody an Ashkenazi/European notion of modernity, positioned in contrast to non-European “tradition,” such as the Yemeni dance performed by Said.

For Daskal and Boutrous’s performance, Grady had them watch YouTube and home videos of Yemeni dance and asked them to “extract Yemeni movement phrases” in performing their “modern” dance.12 When watching the two dances simultaneously, similar gestures and movements indicate that there is a common source material, but what is also made clear is what is lost from the movements in the “modern” dancers’ variation (Figure 2). In Said’s version, the movements appear intentional, purposeful despite their improvisational nature. Said performs them with conviction. In Daskal and Boutrous’s version, similar movements are loose, whimsical—the fact that the dancers are improvising, or “making it up as they go along,” is much more evident. This “watering down” effect that comes from the appropriation of Yemeni culture is also indicated in the choice of the gold and silver leggings worn by the modern dancers—a “‘nod’ to Yemeni embroidery and jewelry-making tradition, [worn] as a way to express [the dancers’] way of appropriating.”13 In the contrasts presented both in terms of appearance and performance, the effects of appropriation on Yemeni dance and culture are articulated.

The creation of a distinctly Israeli culture was imperative in the early formation of the Jewish state. As part of this cultural development, Israeli folk dance took shape. As anthropologist Marie-Pierre Gibert has noted, “Israeli Folk Dance was literally created in the 1940s as a tool for the cultural—and largely political—construction of a ‘new’ Israeli culture.”14 This new cultural identity was rooted in a rejection of European influences—connected with a place of Jewish persecution—and an embrace of “Middle Eastern” influences that legitimized their presence in Palestine.15 In terms of dance, this manifested in the appropriation of indigenous Palestinian dances, such as the dabkeh, which were seen as vestiges of biblical culture that had remained unchanged in the land of Palestine—ready for reclamation or “salvage” by Zionists and subsequently early Israelis.16

With a greater influx of Mizrahi Jews after the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, in particular from Yemen, this cultural appropriation shifted towards Yemeni influences. Much like the claims that Palestinian culture was in fact an indigenous biblical culture frozen in time waiting for reclamation by Zionists in Palestine, the presence of Yemeni (and other Mizrahi) Jews in the region allowed for Jewish claims of presence and connection to the region of the Middle East.17 Ultimately, this Mizrahi Jewish influence was foregrounded over any Palestinian one. As dance scholar Nicholas Rowe remarks, by the early 1950s, prominent Israeli folk dance instructors and choreographers “discuss the ‘rich’ and ‘vibrant’ contributions of the Yemeni Jews and give only passing mention to a vague influence of the more ‘monotonous’ ‘Arab’ dabkehs.”18

This is not to say that this crediting of Yemeni influence was something that was a prominent feature of the Israeli folk dance that adopted it. Mizrahi cultural difference from hegemonic European Ashkenazi Jewry created a problem—while the Yemeni Jews were seen as “authentic,” they were also seen as “backwards” in contrast to European modernity.19 As such, elements of Yemeni culture were appropriated to serve the creation of an “indigenous” Israeli cultural identity, but these influences, and well as the histories of these Yemeni Jewish populations, were subsequently erased and elided to preserve an Ashkenazi dominance. This can be seen in statements by later generations of choreographers and dancers who asserted that Israeli folk dance was something that purely arose from Israeli makers. As one choreographer remarked in the 1970s: “We have the reality that we have created something from nothing.”20 Grady’s video references this erasure of Yemeni influence in Israeli folk dance through the two “modern” dancers who perform without any recognition of the Yemeni musician who creates the music to which they move. Additionally, their performance of a “modern” version of the Yemeni step gestures to the hegemonic culture which places non-Ashkenazi influences and peoples as rooted in the past, and Ashkenazi appropriation of the culture and land as a modernizing project.

The exploitation of Yemeni Jews, when helpful to the Ashkenazi-dominant Zionist cause, and subsequent elision of them, was not limited to the cultural sphere. Yemeni Jewish immigration to Palestine occurred from the late nineteenth century. At various points, this immigration was even encouraged by the Zionist leadership, as they realized they could bring in Yemeni immigrants to take the place of Palestinian Arab agricultural laborers. Using Mizrahi labor was more ideal, they believed, because it promoted a Jewish dominance of the labor force, while still allowing for a profit, as these workers could be paid less than Ashkenazi laborers.21 The Yemeni Jews were in fact referred to as “natural workers”—individuals whose bodies and lifestyles suited the labor, had no other sources or talents for income, and required less to be satisfied.22 This description of Yemeni Jews serves as the title for Grady’s exhibition in which Eye and Heart was displayed. The perception that as natural workers Yemenis are without art, culture, poetry, and dance, serves as the framework his exhibition rejects.

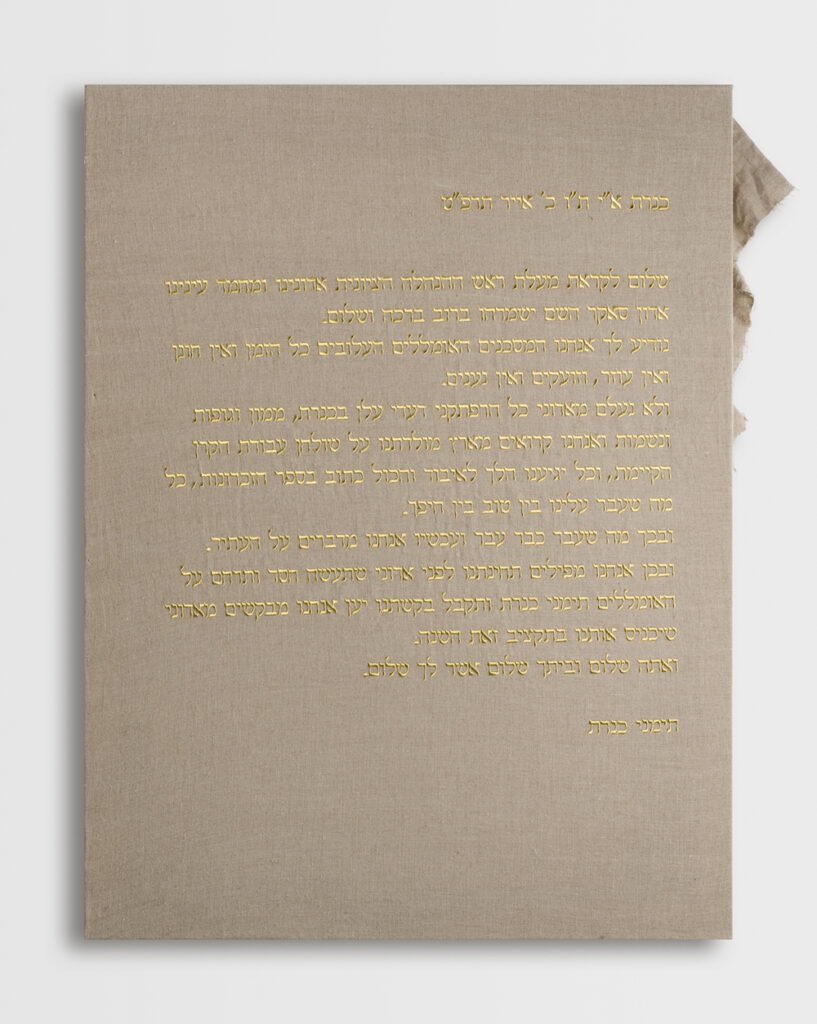

While Eye and Heart demonstrates the appropriation and erasure of Yemeni culture from Israeli culture, another series of works in Natural Worker illustrates the erasure of Yemeni presence from certain parts of the land of Israel, as well as from its history. Among a number of canvases displayed leaning against the gallery walls are four large-scale linen canvases embroidered with Hebrew in gold (Figure 3). The text on these works are transcriptions of four letters, correspondence Grady selected from an assortment he discovered written by early Yemeni Jewish immigrants to the Kinneret (also known as the Sea of Galilee or Lake Tiberias). Dated between 1912 and 1930, the letters consist of complaints to leaders and institutions in charge of the Jewish settlements in Palestine at the time.23 While the letters document frustrations with the lack of support these Zionist institutions were providing, Grady notes in particular the polite, even poetic way that they were written.24

This population of Yemeni Jews had arrived in Palestine in 1912. A year later, a group of new Ashkenazi settlers was given the land to form an agricultural cooperative.25 While the two groups lived side-by-side amicably for a time, by the late 1920s, a scarcity of land and resources, in particular water, resulted in the Ashkenazi settlers petitioning Zionist institutions to resettle the Yemeni population.26 Ultimately, and in spite of letters such as the ones included in Grady’s exhibition, the Yemeni Jews were moved to Rehovot (near Tel Aviv) in 1930 and made to bear witness to their erasure: as they departed, they watched the Ashkenazi settlers already begin to work their land.27 Grady gives this erased history of the Yemeni presence in the Galilee, and the pre-Israeli state Zionist organizations’ disregard for the needs and desires of this population, a place of prominence, not only through increasing the scale of these letters by embroidering them on large stretched linen canvases roughly four-by-three feet in size, but also in using gold thread. The gold, a symbol of luxury, high-status, and a reference to Yemeni craftwork, elevates these letters and the history they tell to a place of honor they never received.28

The letters, which tell the history of the Yemeni experience in, and expulsion from, the Kinneret, also make present voices that have been absented from the histories of early Zionist Palestine and the Israeli state. As Grady notes, in the history of writings about the Kinneret, it is Rachel the poet (Rachel Bluwstein) who is known and associated with the region. Rachel, an Ashkenazi immigrant, spent relatively little time in the Kinneret when compared with the Yemeni population; however, her history and writings are well-known today in Israel, and her association with the Kinneret is solidified through her poem of the same name. On the other hand, the legacy of the Yemeni Jewish population in the Kinneret is not recognized, in spite of the fact that they retain a deep connection to it.29 As Grady has noted, in Yemeni neighborhoods in Rehovot to this day, there are palm trees that were brought from the Galilee, tombstones shaped like the sea, and sand brought from its shores to be placed on graves, even generations later.30 Grady draws out the poetic nature of the Yemeni letters in order to place them in contrast to Rachel the poet. In so doing, he highlights whose history gets told, and whose does not. Rachel embodies the Ashkenazi Zionist ideal, in particular through her use of Ben Yehuda Hebrew. This new modern Hebrew was to become the national language of the new Israeli state, in contrast to the Biblical Hebrew that the Yemeni Jews used (in addition to Arabic). As such, and in spite of the Yemeni history in the area, Rachel and her poetry are centered in the history of the Galilee and early Zionist national formations.31

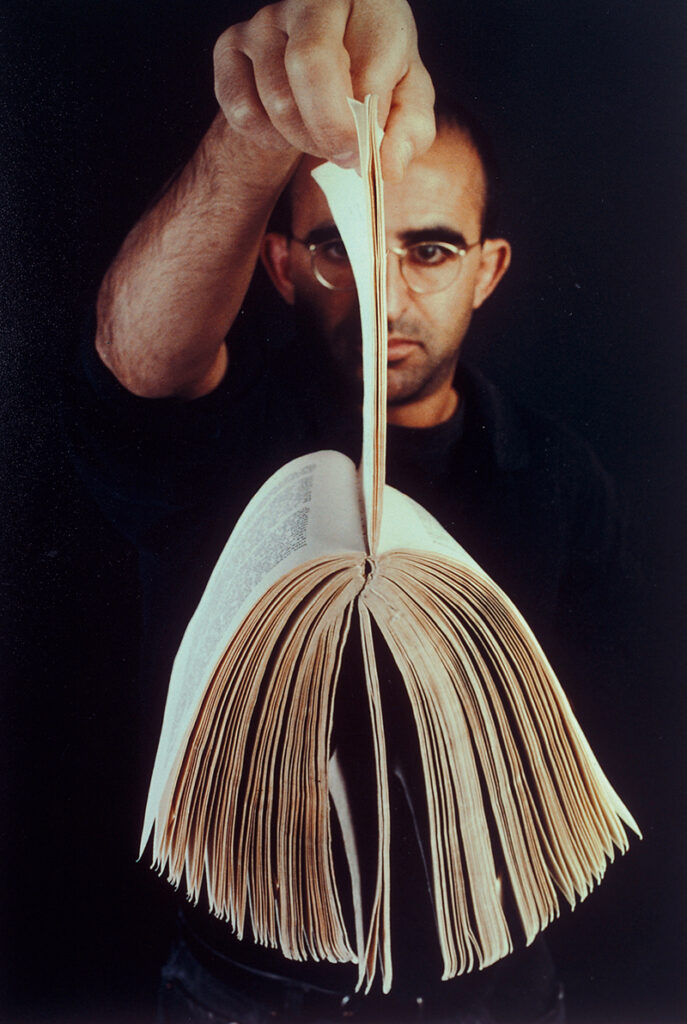

While Grady’s work highlights the erasure of Yemeni presence in the Galilee from Zionist Israeli history, this sort of erasure is one that is pervasive when it comes to the Mizrahi community, and which has been remarked upon in works by other Mizrahi artists.32 Meir Gal highlights the erasure of Mizrahi history in his work Nine Out Of Four Hundred (The West And The Rest) (Figure 4).33 The work is comprised of an image and accompanying text. In the image, what the artist refers to as a “photo performance,” Gal holds up the official Israeli textbook on the history of the Jewish people used by high school students, including the artist, in the 1970s.34 He clasps the book, holding it up between his fingers by a handful of pages, allowing the thick text to splay out on either side, the two halves appearing like drooped wings, weighted down by the heft of the remaining pages.35 Gal is holding onto the book by the nine pages that make up the discussion of non-European contributions to Jewish history included in the text. As noted in the title, this is only nine out of the four hundred pages that make up the tome. The remaining pages, as indicated by the subtitle of the work, comprise the majority of this history—that of European/Ashkenazi Jews. As Gal notes in the text that accompanies the image, his “intention is to put an end to the speculative character of the argument whether or not Mizrahim have been discriminated in Israel.”36 Grady’s exhibition too highlights that this is a history that continues to be erased.37 The impact of the historical erasure that Grady’s letter canvases bring to the fore is evident in the resultant textbooks that are used in Israeli schools, featured in Gal’s work, and the continued influence on Israeli arts and culture, made evident in Grady’s Eye and Heart.

Despite the fact that Mizrahi Jews make up half of the population in Israel, Ashkenazi identity, history, and claims to culture continue to dominate.38 From the start, the Zionist project was an Ashkenazi one, only utilizing Mizrahi labor and culture as best served it. As Middle Eastern studies scholar Joseph Massad has noted, “The Zionist movement’s European identity was asserted from the outset in its classic texts. Theodor Herzl declared that the Jewish state would serve as ‘the portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.’ When discussing Jewish immigration, he spoke only of European Jews.”39 Discrimination against Mizrahi Jews was also clear from the early stages of immigration to Mandate Palestine and later Israel. In addition to being relocated like the Kinneret Yemeni settlers, Mizrahi arrivals to Israel were placed in poor conditions upon arrival, many of them being directed to transit camps, a liminal site that often became a multi-year residence. At the same time, Ashkenazi immigrants were given former Palestinian homes.40 Meanwhile, Mizrahi immigrants were also subjected to humiliating and dangerous “cleansing” procedures—such as the use of DDT to “disinfect” immigrants, and the practice of “kidnapping . . . hundreds of Yemeni children from transit camps in Israel and giving them to childless Ashkenazi couples for adoption.”41 Mizrahi immigrants were given poorer land, fewer social services, and lower wages; gaps in salary, employment, and education between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi Israelis persist to this day.42 Likewise, governmental support has favored Ashkenazi lifestyles, as cultural studies scholar Ella Shohat has highlighted: “The government . . . subsidizes certain basic dietary staples, one of them being European-style bread; the pita favored as a staple by both Sephardim [here used interchangeably with Mizrahi] and Palestinians, meanwhile, is not subsidized.”43 At all levels of Israeli society, government, and culture, an Ashkenazi dominance prevails at the expense of Mizrahi, as well as Palestinian, populations.

Leor Grady’s video work Eye and Heart and the letter canvases exhibited in Natural Worker make clear the cultural and historic influences of the Yemeni population on the Israeli state and formation of Israeli national identity. They also highlight how Yemeni culture and history has been appropriated and elided. In the relationship Grady sets up between the cultural appropriation of Yemeni dance into Israeli folk dance, embodied by his video, and the erasure of the historic Yemeni presence in the Kinneret, articulated in his embroidered linen letters, the artist demonstrates how Israel’s national identity and contemporary reality rest on a persistent erasure of its Yemeni (and more broadly, Mizrahi and Arab) influences.44 As the works highlight, the formation of the new Jewish state and a national Israeli identity centered around a European (white) Jewish identity, despite this formation’s reliance on non-Ashkenazi labor and culture.

In considering the white European roots of Ashkenazi hegemony in Israel, and taking into account the white supremacy that dominates in the English-speaking world (the primary audience for this article), it is impossible to ignore that the white supremacy that exists in the these regions (Europe, the United States, and Canada) is also distinctly anti-Jewish. However, while this aspect of Euro-American white supremacy does not manifest in the context of Israel, the rhetoric from the founders and historical leaders of the Zionist movement and the history of Ashkenazi treatment of Mizrahi Jews in Israel makes clear the racialized nature of the Zionist project.45 It is not incidental that, for example, American alt-right white nationalists cite Israel as an example of the “ethno-state” that they seek in the United States.

It must also be noted that the racist discrimination against Palestinians in Israel is not limited to the Ashkenazi Jewish population. In fact, as anthropologist Smadar Lavie has shown, while the Ashkenazi population tends to vote for the “Left” in Israel, the Mizrahi majority population overwhelmingly votes for right-wing politicians.46 This tendency appears to be rooted in a desire to gain greater power within the Israeli context through affirming Jewish religious affiliations over racial Arab ones, something into which the right-wing parties feed. Right-wing government investment in the lower-class communities of the Mizrahi population, as well as support of its culture “as long as it [Mizrahi culture] avoided connecting its own Arabness with that of the Palestinians” has contributed to this support.47 Anecdotally, Mizrahi Israelis have noted that those who have been able to integrate themselves into Ashkenazi culture, in sacrifice of any Arab identification, have most been able to benefit from improved status within Israel.48

In a 2019 opinion piece for Al Jazeera, Tony Greenstein, a British anti-Zionist Jew and founder of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, compared the Mizrahi population to the poor white population in the United States—while they are oppressed by the dominant (white) population, they displace this frustration onto an alternative scapegoat, encouraged by the right wing—African Americans and Latinx individuals in the US, and Palestinians in Israel.49 While Greenstein uses the comparison of Mizrahi Jews to the poor white population in the United States to argue that the Jewish nationalist project is Jewish-supremacist, rather than white supremacist, I contend that in the context of Israel, these go hand-in-hand. The Mizrahi population’s desire to distinguish themselves from the Palestinian population and improve their position is a desire for proximity to power in Israeli society—a position rooted in white Ashkenazi identification. Within the context of Israel, Ashkenazi hegemony references a distinctly ethnic/racial identification—it is rooted in white supremacy. The historic entrenchment of Israel’s national identity in Ashkenazi (white European) superiority and dominance is important to draw out, as Leor Grady’s work does, in order to understand the roots of the Zionist state, and the nuances in which racist practices manifest throughout Israel and the Palestinian Territories. In the face of more overt instances of racial discrimination in arenas like policy, the arts and cultural appropriation can appear to be less urgent sites of intervention. However, as Grady’s exhibition Natural Worker makes clear in the inclusion of Eye and Heart alongside the letter canvases, the arts and culture are spaces where the legacy of more overtly discriminatory policies can insidiously manifest. The erasure of these histories and cultural influences both serve to create and reaffirm a notion of Israeli identity that is rooted in Ashkenazi whiteness, perpetuating an Ashkenazi white supremacy in Israel that allows for racially discriminatory policies to persist.

Acknowledgements

This article was made possible through the support of research assistance provided by Jinan Abufarha through the UROP (Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program) at the University of Michigan, and generous conversations via Skype and email with Leor Grady. My thanks also to the anonymous reviewers, Anne Marie Butler, SJ Crasnow, and Forum Editor Rayya El Zein for their feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Notes

- Of Middle Eastern descent. ↩

- Of (largely Eastern) European descent. This excludes Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, who are classified as Sephardic Jews. Sephardic and Mizrahi are sometimes used interchangeably, and sometimes Sephardic is associated with a set of differentiated (from Ashkenazi) religious practices rather than ethnic affiliation. For robust discussions of the histories, usages, and differentiations between these terms, and others that have been used, see Sami Shalom Chetrit, Intra-Jewish Conflict in Israel: White Jews, Black Jews (London: Taylor & Francis, 2009); Harvey E. Goldberg, “From Sephardi to Mizrahi and Back Again: Changing Meanings of ‘Sephardi’ in its Social Environments,” Jewish Social Studies 15, no. 1 (2008): 165–188; Smadar Lavie, “Introduction,” in Wrapped in the Flag of Israel: Mizrahi Single Mothers and Bureaucratic Torture, revised ed. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 1; and Ella Shohat, “The Invention of the Mizrahim,” Journal of Palestine Studies 30, no. 1 (Autumn 1999): 5–20. ↩

- In the United States, a related but different manifestation of the dominance of Ashkenazi (white) Jewishness as the presumptive Jewish identity is referred to as Ashkenormativity. Other non-Ashkenazi Jewish populations could also serve as examples of the varied ways racism manifests within the Jewish population and government of Israel, perhaps most notably the Ethiopian Jewish population. For a discussion about this population, see Uri Ben-Eliezer, “Multicultural society and Everyday Cultural Racism: Second Generation of Ethiopian Jews in Israel’s ‘Crisis of Modernization,’” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31, no. 5 (2008): 935–961; Steven Kaplan and Hagar Salamon, “Ethiopian Jews in Israel: A Part of the People of Apart from the People?” in Jews in Israel: Contemporary Social and Cultural Practices, ed. Uzi Rebhun and Chaim Isaac Waxman (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2004); Nissim Mizrachi and Hanna Herzog, “Participatory Destigmatization Strategies among Palestinian Citizens, Ethiopian Jews, and Mizrahi Jews in Israel,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35, no. 3 (2012): 418–435; and Durrenda Ojanuga, “The Ethiopian Jewish Experience as Blacks in Israel,” Journal of Black Studies 24 , no. 2 (December 1993): 147–158. ↩

- Ronit Lentin, Traces of Racial Exception: Racializing Israeli Settler Colonialism (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018). ↩

- For a social history of Mizrahi Jews in Israel see Yehouda Shenhav, The Arab Jews: a Postcolonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006). On literature, see Ammiel Alcalay, After Jews and Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993); Kfir Cohen, “Mizrahi Subalternity and the State of Israel: Towards a New Understanding of Mizrahi Literature,” Interventions 16, no. 3 (May 4, 2014): 380–404; Hannan Hever, “We Have Not Arrived from the Sea: a Mizrahi Literary Geography,” Social Identities 10, no. 1 (2004): 31–51; and Yochai Oppenheimer, “Mizrahi fiction as Minor Literature” in Contemporary Sephardic and Mizrahi Literature: A Diaspora, ed. Dario Miccoli (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2017). On film, see Ella Shohat, Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989). ↩

- While the majority of the world’s Jews are white/Ashkenazi, the majority of these reside outside of Israel, while the majority of Mizrahi Jews, who make up the minority of the world Jewish population, live within Israel—making up half of the population there. Recently, imagery coming out of Israel has become more inclusive of Mizrahi faces. However, the motivations behind this, to refute international (especially American) claims that Israel is white supremacist/racist/settler colonial through a demonstration that the population includes non-white Jews, has been criticized as “Mizrahi-washing.” For a longer discussion of this, see Lihi Yona, “Mizrahi-Washing: The New Face of Israeli Propaganda,” +972 Magazine, June 25, 2020, https://www.972mag.com/mizrahi-washing-hasbara-israel-propaganda. ↩

- The first time this work was shown was as a two-channel video installation. Since then it has been shown with the two dances side-by-side as a single channel video. Email from Grady to the author, March 4, 2020. ↩

- The dances were filmed at the Inbal Dance Theater in Tel Aviv. ↩

- Grady notes that historically, Yemeni Jews avoided the use of “real” instruments as a way to mourn the destruction of the biblical temple, instead using found objects, such as the olive oil tin. Email from Grady to the author, December 4, 2019. ↩

- Since the making of the video, Said has become much more interested in dance, and now gives workshops on modern Yemeni dance. Email from Grady to the author, December 4, 2019. ↩

- Gili Izikovich, “This Israeli Arab Artist Doesn’t Want to Be Labeled ‘The Arab Choreographer,’” August 27, 2018, Ha’aretz https://www.haaretz.com/life/MAGAZINE-please-don-t-label-this-israeli-arab-artist-the-arab-choreographer-1.6415739. ↩

- Skype conversation between Grady and the author, November 22, 2019, and email from Grady to the author, December 4, 2019. ↩

- Email from Grady to the author, December 4, 2019. ↩

- Marie-Pierre Gibert, “The Intricacies of Being Israeli and Yemenite. An Ethnographic Study of Yemenite ‘Ethnic’ Dance Companies in Israel,” Qualitative Sociology Review 3, no. 3 (2007): 104. ↩

- Nicholas Rowe, “Dance and Political Credibility: The Appropriation of Dabkeh by Zionism, Pan-Arabism, and Palestinian Nationalism,” Middle East Journal 65, no. 3 (Summer 2011): 364–366. ↩

- This notion of a culture frozen in time unchanged is also a common colonialist framework imposed by colonizers on the culture of the colonized—seen as “primitive” and “backwards” in contrast to the colonizers’ “modernity.” Rowe, “Dance and Political Credibility,” 365. ↩

- The 1950s in particular brought Mizrahi Jews to the new state of Israel, from “places such as Morocco, Libya, Egypt, Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, Bulgaria, former Yugoslavia, and India.” Note that the definition of Mizrahim can include not only Jews from Arab countries in the Middle East and North Africa, but also Turkish, Persian, South Asian, and Balkan Jews. Lavie, “Introduction,” 1. ↩

- Nicholas Rowe, Raising Dust: A Cultural History of Dance in Palestine (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 89. ↩

- Sivan Rajuan Shtang, “Strange Bouquet—on Leor Grady’s Works,” in Leor Grady: Natural Worker, trans. Sivan Raveh (New York: Sternthal Books, 2018), 24. Exhibition catalogue. ↩

- Rowe, Raising Dust, 90. ↩

- Gershon Shafir, “The Meeting of Eastern Europe and Yemen; ‘Idealistic Workers’ and ‘Natural Workers’ in Early Zionist Settlement in Palestine,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 13, no. 2 (1990): 176–77. ↩

- Skype conversation between Grady and the author, November 22, 2019, and Shafir, “Meeting of Eastern Europe and Yemen,” 180. ↩

- Email from Grady to the author, January 2, 2020. ↩

- Skype conversation between Grady and the author, November 22, 2019, and email from Grady to the author, January 2, 2020. ↩

- Gabriel Piterberg, “Domestic Orientalism: The Representation of ‘Oriental’ Jews in Zionist/Israeli Historiography,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 23, no. 2 (1996): 140. ↩

- Piterberg, “Domestic Orientalism,” 140. ↩

- Piterberg, “Domestic Orientalism,” 140. ↩

- Ouzi Zur, “Tel Aviv Art Show Shines Spotlight on the Rejects of the Zionist Consensus,” January 14, 2017, Ha’aretz, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/culture/.premium-art-show-shines-spotlight-on-zionist-consensus-rejects-1.5485396. ↩

- Skype conversation between Grady and the author, November 22, 2019. ↩

- Skype conversation between Grady and the author, November 22, 2019. ↩

- Skype conversation between Grady and the author, November 22, 2019. ↩

- While Grady focuses on this particular moment in Yemeni Jewish history in Israel, it is one of a series of significant moments in this history. Two other particular moments worth noting are Operation Magic Carpet (1949–1950) when forty-nine thousand Yemeni Jews were brought to Israel and the “Yemenite Children Affair” when large numbers of Yemeni, Mizrahi, and Balkan Israeli children (officially at least one thousand, with some speculations of as many as 4,500) went missing. ↩

- My thanks to Leor Grady for introducing me to this work. ↩

- Meir Gal, “Nine Out Of Four Hundred (The West And The Rest) 1997,” https://www.meirgal.com/#/nine-out-of-four-hundred-1997. ↩

- Gal, “Nine Out Of Four Hundred.” ↩

- Gal, “Nine Out Of Four Hundred.” ↩

- Gal, “Nine Out Of Four Hundred.” The full text that accompanies the image to comprise the work is reproduced here:

Since the establishment of Israel we have heard mostly from and about its European (Ashkenazi) Jews. Numerous books and articles have depicted the State of Israel as a country which has successfully managed to bring together people of different ethnic origins. Unfortunately, these publications have created a perception that is far from the realities non-Ashkenazi groups have had to endure. Mizrahim (Jews of Asian and African origins, and Arab Jews, commonly referred to as Sephardim) who have written extensively about the discrimination against Mizrahim in Israel and who have documented the history of Mizrahi resistance have been censored and criticized. To this day, Mizrahi activists in Israel are marginalized and often excluded from public positions and funding.

The official textbooks on the history of the Jewish people used in Israeli schools are dedicated almost exclusively to the history of European Jewry. For decades the Ministry of Education systematically deleted the history of Jews who came from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. These books helped establish a consciousness that the history of the Jewish people took place in Eastern Europe and that Mizrahim have no history worthy of remembering. The origins of this policy date back to the mid 1800’s to the Ashkenazi treatment of the Mizrahi diaspora prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. Both Jewish European communities as well as the Jewish Eastern European leadership in Palestine (and later in Israel), categorized non-European Jews as backward and primitive. Cautionary measures in the form of selective immigration policies were enacted in the 1950’s in order to reduce the “dangerous Levantine influence” of non-European cultures on the new Israeli entity.

Mizrahim historically suffered no contradiction between being a Jew and an Arab simultaneously. The advent of Zionism and the establishment of the Israeli State drove a wedge between Mizrahim and their origins, and replaced their Jewish – Arab identity with a new Israeli identity based on European ideals as well as hatred of the Arab world. From the moment of their arrival in Israel, Mizrahim were forced to deny their Jewish-Arab identity which they had held for centuries in Arab countries and in Palestine. The inevitable outcome was an irreconcilable Mizrahi denial of its own past which gradually evolved into self-hatred. The severe racial conflict within Israel, its resulting class division as well as its impact on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, is absent from most discourse on Middle Eastern history and politics.

The book shown in the photograph is the official textbook of the history of the Jewish people in recent generations that was used by high school students (including myself) in the 1970’s. The nine pages I’m holding are the only pages in the book that discuss non-European Jewish history. Hence the title: Nine Out of Four Hundred (The West and the Rest). My intention is to put an end to the speculative character of the argument whether or not Mizrahim have been discriminated in Israel. Today the Ministry of Education continues to erase the history of its non European Jews despite the fact that they comprise more than half of the Israeli population. This is only one example of how the State of Israel continues to minoritize its non-European majority. - Lavie, Wrapped in the Flag of Israel, 1. ↩

- Interestingly, as Massad goes on to note, Algerian Jews were included in Herzl’s definition of European Jews. Joseph Massad, “Zionism’s Internal Others: Israel and the Oriental Jews,” Journal of Palestine Studies 25, no. 4 (Summer 1996): 54. ↩

- Massad, “Zionism’s Internal Others,” 56–57. When Mizrahi immigrants were given permanent homes in former Palestinian housing, oftentimes multiple families were placed into the same home under the assumption that these were their typical living conditions. Ella Shohat, “Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of its Jewish Victims,” Social Text 19/20 (Autumn 1988): 18. ↩

- Massad, “Zionism’s Internal Others,” 56–57. For more on transit camps, see Orit Bashkin, Impossible Exodus: Iraqi Jews in Israel (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017), 8–9. ↩

- Yona, “Mizrahi-Washing.” ↩

- Shohat, “Sephardim in Israel,” 22. ↩

- While the experiences of various Mizrahi populations upon arrival to Israel have been different, and the difference in their experiences important to note, since the 1980s, Mizrahi as a collective term has been utilized productively to think about these collective, while differentiated, experiences in contrast to those of Ashkenazi Jews in Israel. As Sami Shalom Chetrit has noted, “The new self-coined term, Mizrahim, heard since the early 1980s together with the appearance of a new Mizrahi political discourse, is mainly a social-political term, based to a lesser degree on ethnic origins. The starting point for those calling themselves Mizrahim is a view of Israeli society in terms of economic and cultural oppression of non-Europeans by Europeans in general, and of Mizrahim by Ashkenazim in particular.” Chetrit, Intra-Jewish Conflict, 40. Taking this into consideration, it is worthwhile examining Grady’s work through both the lens of the historical context of the Yemeni experience in Israel, and particularly the Kinneret, as well as the broader contemporary realities (effected by their historical roots) of Mizrahi Jews in Israel more broadly. ↩

- There are differences in how Mizrahi Jews are racialized and classed depending on their country of origin as well. For more on this, see Bashkin, Impossible Exodus, 5–13. Though as Bashkin also notes, these various Mizrahi communities also have shared/parallel experiences. ↩

- Smadar Lavie, “Mizrahi Feminism and the Question of Palestine,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 7, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 65–66. For more about the history of Mizrahi involvement in electoral politics in Israel see Sami Shalom Chetrit, “Mizrahi Politics in Israel: Between Integration and Alternative,” Journal of Palestine Studies 29, no. 4 (2000): 51–65.

It is interesting to note that, according to Grady, the Yemenis in Rehovot, the descendants of the Kinneret Yemeni population, still traditionally vote Labor (center-left). Skype conversation between Grady and the author, November 22, 2019. ↩ - Lavie, “Mizrahi Feminism,” 68. ↩

- “Israel’s Great Divide,” Al Jazeera World, July 13, 2016, https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/aljazeeraworld/2016/07/israel-great-divide-160712124159372.html. ↩

- Tony Greenstein, “Why Israel is a Jewish, not a White Supremacist State,” Al Jazeera, February 7, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/israel-jewish-white-supremacist-state-190207100801951.html. ↩