Frederick Douglass described the notion of a sovereign subject as a “contradiction in terms” and an absurdity. “When sovereignty becomes subject,” he argued, “it ceases to be sovereignty.”1 Hannah Arendt came to a similar conclusion a century later, claiming that the idea of a sovereign subject is not only absurd, but attempts to enact it are prone to violence. For this kind of subject, she argued, freedom can be “purchased only at the price of the freedom, i.e. the sovereignty, of all others.”2 This was certainly true of the sovereignty Douglass subjected to critique, namely, the popular sovereignty championed by White slaveholders, who conceived of their freedom as the logical entailment of Black subjugation.

Douglass’s and Arendt’s critiques provide useful insights into notions of freedom and security popular within US gun culture, i.e. freedom as radical independence and personal security as the elimination of vulnerability.3 With the politicization of US gun culture since the 1970s, it has become commonplace to view individual freedom and security as dependent upon or even synonymous with the reclamation of traditionally defined sovereign powers, including the power over life and death (vitae necisque potestas).4 Today, individual and popular sovereignty are increasingly invoked as justifications for armed vigilantism, reminding us of some of the darkest periods in US history, when extra-legal violence was regularly employed to sustain the private tyranny of racialized rule.5

I have divided my discussion into two parts. In the first, I outline the ways in which the exercise of popular sovereignty is a social relation of rule that often involves extra-legal forms of violence. These practical forms of rule regularize unequal levels of vulnerability and security among various groups, which in turn enable juridical normalization. In the second part, I address how the sovereign subject, thought to be at the root of popular sovereignty, is conceptually contradictory and practically self-defeating. Conceptually, popular sovereignty emerges only at the moment of its alienation, i.e. retroactively, thus making the project of recuperating the sovereign subject an infinitely receding and ultimately unfulfillable promise. In practice, attempts to return to a supposed pre-political condition of personal sovereignty in order to secure individual freedom has involved dismantling precisely the social conditions that enable such freedom in the first place.6

Popular Sovereignty and Lawless Violence

Frederick Douglass’s critique of the sovereign subject is found in his speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Bill (1854). In that speech, he passionately opposed the bill’s empowerment of local Whites to determine whether slavery would be allowed in the Kansas and Nebraska territories. At the time, this decision-making power about slavery had become synonymous with popular sovereignty, despite the public critiques of detractors like Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.7 Of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, Douglass wrote, “The sovereign right to make slaves of their fellowmen if they choose is the only sovereignty that the bill secures.”8 This critique was informed by a deep commitment to what Douglass took to be true popular sovereignty, namely, the “right of the people to establish a government for themselves,” and it had two parts.9 First, Douglass rejected the association of popular sovereignty with White rule and slavery, for it excluded Black participation in the sovereignty of “the people.” Second, he thought the White supremacist interpretation of popular sovereignty relied on a conceptual contradiction, namely, the sovereign subject. I take up Douglass’s conceptual argument and its contemporary relevance in the next section.

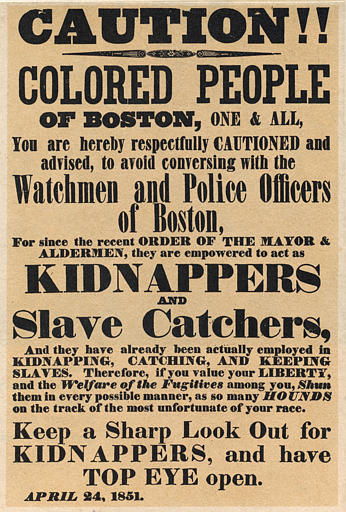

Douglass’s critique of the association of popular sovereignty with slavery begins with a consideration of law and, in particular, his claim that there has never been a state or federal law that established slavery in the United States. There existed innumerable legal regulations, of course, but the institution itself was never legally established. “It is now, and always has been,” he says, “a system of lawless violence.”10 This encourages us to, as Orlando Patterson later advocated, consider slavery as a “relation of domination rather than as a category of legal thought,” and thus to inquire how sovereignty manifests in relations of rule beyond the law.11 In support of his claim, Douglass alluded to a statement by James Murray Mason, the Virginia Senator and author of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. When a critic of Mason’s bill proposed an amendment requiring, upon capture, evidence of the legality of slavery in the state from which the enslaved person escaped, Mason was left without a defense. He replied that “no such proof can be produced,” for he was “not aware that there is a single State in which the institution is established by positive law.” Moreover, he added, “no such law was necessary for its establishment.”12

Mason was relying on an assumption that White rule was simply a fact of the social order, prior to any legal categorization or regulation. Although Mason sought to naturalize White rule, it was of course the result of sustained coercion and brutality. The creation of the practical conditions to which a juridical norm can later be applied, is an example of what Carl Schmitt called the “absolute form” of exception that characterizes sovereign power.13 We could interpret the “system of lawless violence” Douglass referred to as such an absolute form of exception, regularizing social relations and thus engendering the iterability necessary for legal norms to take hold. One is reminded here of the South Carolina Regulators of the 1760s, whose “lawless methods,” wrote historian Richard Maxwell Brown, “had achieved their end, paradoxically, in the establishment of law and order.”14

One type of regularity produced by these extra-legal forms of racialized rule is increased precarity and vulnerability to violence on the part of those subject to domination. The historian J. M. Opal describes the need of Whites in antebellum America to “find sovereignty where the law did not reach” and this “promise of greater sovereignty” was “directly tied to the enhanced misery of black and native peoples.”15

Their enhanced sovereignty required both the degradation of others and a certain kind of chaos in the nation at large: the daily freedoms for some to go armed, to seize lands, to vote, to take offense, and to threaten; the daily demands on others to retire, to hide, to bear quietly, and to forgive.16

Mason’s Fugitive Slave Act is an instance of this phenomenon insofar as it magnified the already disproportionate epistemic authority of Whites, particularly of White men.17 By legally recognizing the claim of a White person to any Black person as their fugitive property, without documentation, the Fugitive Slave Act formalized the epistemic authority of Whites to render Black communities vulnerable to arbitrary violence. “Each and all of us [has been] reduced to the mercy or discretion of any white man in the country,” wrote Martin R. Delany, Douglass’s coeditor at the North Star newspaper.18

The pursuit of White sovereignty as social domination beyond the law also manifested in a variety of exclusionary economic practices, private militias, and vigilante patrols.19 After the Civil War, unofficial police forces were created to enforce economic benefits for Whites, while communities of color were routinely subject to intimidation and violence by organized gun clubs and voluntary militias, sometimes referred to as “mutual aid clubs.”20 These White vigilante groups, including most famously the Ku Klux Klan, were explicitly dedicated to suppressing Black freedom, disarming Black groups, and in general producing a condition of increased Black vulnerability.21

The experience of vulnerability is inseparable from the social conditions that enable our freedom and security. We are all fundamentally vulnerable insofar as our identities are constituted through relations of social recognition beyond our individual control and those identities are physically embodied, hence exposing us to potential harm. However, groups experience vulnerability unequally, because the level of risk to which we are exposed depends in part on our social location within relations of rule.

Despite the indelible human condition of vulnerability, the desire of the sovereign subject is to assert complete control over these forms of exposure, to withdraw from social interdependencies that render it vulnerable, and to vigilantly police the newly drawn boundaries of a radically independent self. “The sovereign subject,” writes Judith Butler, “poses as precisely not the one who is impinged upon by others, precisely not the one whose permanent and irreversible injurability forms the condition and horizon of its actions.”22 This task of preempting one’s own injurability comes at the cost of the other’s freedom, for the conditions and possibilities of their actions must be determined by the will of others.

The Sovereign Subject as Contradictory and Self-Defeating

The myth of the sovereign subject is that the complete elimination of such vulnerability is possible, that the assertion of this control enables true freedom, and that such freedom existed at one point in the past, namely, before the powers of the sovereign subject were alienated to others. The freedom said to be regained through the reclamation of sovereignty is understood as independence from influence exercised beyond the self-legislative and coercive capacities of the subject. Like the lord in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, who initially and mistakenly sought freedom through the subjection of the other (i.e. the bondsman), the pursuit of this freedom shifts violability and heteronomy to others.23 “Such a sovereign position,” wrote Butler, “not only denies its own constitutive injurability but tries to relocate injurability in the other as an effect of doing injury to that other and exposing that other as, by definition, injurable.”24

The desire to become an inviolable subject fuels the disavowal of the social norms and relations that simultaneously make us vulnerable and form “the condition and horizon” of our actions. If we cannot accept the vulnerability associated with the social conditions that enable our action and thus our freedom, and we cannot extract ourselves from them, then the authoritarian impulse to assert one’s will over these conditions—including the wills of others—soon presents itself. The attempt to achieve inviolability through detachment thus turns into the construction of a private form of rule performed upon and through the bodies of others. Whether or not such rule becomes legally recognized, it represents the substitution of one form of mutual dependency, which is relatively stable and mutually enabling, with another, more destabilizing and coercive kind.

Douglass’s conceptual critique of this purported sovereign subject is informed by the seemingly paradoxical nature of popular sovereignty itself, namely, that sovereignty emerges at the moment of its alienation from the people. “When what was future becomes the present,” writes Douglass, “it ceases to be the future and so with sovereignty and subjection, they cannot exist at the same time in the same place, any more than an event can be future and present at the same time.”25 The subjects in whom sovereignty originates cannot simultaneously possess sovereign power, for this power only arises after the collective act of consent. In other words, the constituent power of the people to create sovereignty, i.e. to authorize the rule of others, is not itself sovereign power. “The people are a sovereign which cannot exercise sovereignty,” wrote Joseph de Maistre.26

To clarify the distinct moments of this relation, it is helpful to distinguish the power to constitute from the power to command, not unlike the way Cicero distinguished the power of the people (potestas in populo) from the authority (auctoritas) of the Senate.27 This does not, however, completely capture the logic at work here. Jacques Derrida has, for example, demonstrated how a unidirectional understanding of the present and future, like the one Douglass holds, fails to comprehend the multidirectional nature of this constituent power: It produces both the sovereign and, retroactively, the people. In the signing the US Declaration of Independence, for example, the people also constitutes itself as a subject capable of such authorization. The people, wrote Derrida, “does not exist, before this declaration, not as such. If it gives birth to itself, as free and independent subject, as possible signer, this can hold only in the act of the signature. The signature invents the signer.”28

The fundamental conceptual problem with the sovereign subject is, according to Douglass’s critique (with a Derridean addendum), that it fails to recognize sovereignty and subject as emergent properties and thus falls prey to the fallacy of division. It tends to view political sovereignty as the aggregate of individual sovereign powers, like Abraham Bosse’s famous seventeenth-century frontispiece for Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan in which the body of the sovereign is composed of a multitude of individuals. From this perspective, political sovereignty is merely an aggregation and thus disaggregation would result in a multitude of sovereign subjects. The Executive Director of Gun Owners of America, Larry Pratt, recently put it this way: “the way for Americans to regain the sovereignty that has slipped unconstitutionally into the hands of our rulers, is for Americans to once again carry guns.”29 Sovereignty could then be exercised immediately as self-rule, often viewed as true freedom, rather than mediated through a collective fiction—“the people”—that unequally distributes command and subjection.

Douglass rightly called this notion of sovereignty an absurdity and although there is a long American tradition of conflating sovereignty and freedom, not distinguishing them is perilous. Arendt argues that the association of freedom and sovereignty is “the most pernicious and dangerous consequence” of the long and problematic identification of political freedom and free will.30 Freedom as free will is divorced from acting in the world with others and becomes fully internalized, immaterial.31 Freedom as sovereignty is only achievable through the subjection of others, for sovereignty is the power of command, the power to make and enforce laws “without any dictation or interference from any quarter,” as Douglass described it.32 “If it were true that sovereignty and freedom are the same,” Arendt concludes, “then indeed no man could be free, because sovereignty, the ideal of uncompromising self-sufficiency and mastership, is contradictory to the very condition of plurality.”33 Rather than reclaim freedom, the pursuits of the sovereign subject result in the active denial of freedom and security for others and, in a self-defeating turn, for itself as well.

Conclusion

The more passionately one identifies with an abstract notion of freedom, such as free will, the less likely one is to be socialized through mutually recognized norms that enable relations of trust and practices of social cooperation. The dilemma of the sovereign subject is that an armed retreat into the self in pursuit of sovereignty undermines these social conditions of freedom. Indeed, Arendt goes so far as to claim: “If men wish to be free, it is precisely sovereignty they must renounce.”34 Moreover, the attempt to shore up the boundaries of the self to ensure non-interference produces a highly agitated and vigilant disposition that is perpetually suspicious of others. Enemies abound when shared norms are rejected as unwelcome constraints, and the boundaries of the political community extend no further than one’s silhouette. Sovereign power, wrote Alexander Hamilton, brings with it “an impatience of control that disposes those who are invested with the exercise of it to look with an evil eye upon all external attempts to restrain or direct its operations.”35 Although sovereign citizens are the most extreme example of this unending self-defensive posture, the insatiable desire for “absolute protection” can be found throughout contemporary gun culture, from Stand Your Ground to, most significantly, the landmark case District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), which for the first time interpreted the Second Amendment as guaranteeing an individual’s right to possess a firearm for self-defense.36

It is hardly surprising that Richard Hofstadter, who famously penned an account of the paranoid style of American politics, was an early and astute observer of the NRA’s resistance to gun control legislation. In 1970, Hofstadter ended his American Heritage article titled “America as a Gun Culture” with a question: “One must wonder how grave a domestic gun catastrophe would have to be in order to persuade us [to accept regulation]. How far must things go?”37 Approximately fifty years later, we can answer with confidence that no gun catastrophe, no matter how grave, could ever weaken the resolve of aspiring sovereign subjects to possess such means of coercion. Indeed, the most spectacularly violent and devastating consequences of its own commitments appear only as evidence of the necessity of the sovereign subject’s goal, which is neither physical safety nor political freedom, but the protection of extra-legal forms of rule that render the lives of others more precarious.38 If, however, intimidation, coercion, and private tyranny are what result from the actions of the sovereign subject, resistance to them is justifiable in the defense of freedom, and not only, as is most common, for reasons of public health or personal safety. It might then be productive to rephrase Hofstadter’s question from a half century ago: Since the threat to freedom posed by the sovereign subject of US gun culture is so grave, how far should a countermovement be willing to go to stop it?

Notes

- Frederick Douglass, “The Kansas-Nebraska Bill speech, November, 1854,” in The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass: Volume II, Pre-Civil War Decade, 1850–1860, ed. Philip S. Foner (New York: International Publishers, 1950), 330. ↩

- Hannah Arendt, “What is Freedom?” in Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought (New York: Viking Press, 1954), 164. ↩

- According to a recent study, three-quarters of all gun owners—of whom the largest demographic is White men—believe their right to own firearms is essential to their personal freedom. Half of all gun owners believe firearms are important to their identity. Pew Research Center, “America’s Complex Relationship With Guns,” June 2017, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/06/22/americas-complex-relationship-with-guns/. The NRA Executive Vice President, Wayne LaPierre, spoke to the increased saliency of absolute security in his famous “good guy with a gun” speech: “The only way to stop a monster from killing our kids, is to be personally involved and invested in a plan of absolute protection.” “Transcript: Statement by National Rifle Association’s Wayne LaPierre, Dec. 21, 2012,” MassLive, last updated March 24, 2019, https://www.masslive.com/news/index.ssf/2012/12/transcript_statement_by_nation.html. ↩

- In Harvest of Rage, Joel Dyer observes that “anti-government behavior in Rural America,” by which he meant the Posse Comitatus, Christian Identity adherents, and right-wing militias of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, “is becoming increasingly tied to the idea of the sovereignty of the individual.” Joel Dyer, Harvest of Rage: Why Oklahoma City is Only the Beginning (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997), 174. The growing sovereign citizens movement today, which continues this tradition, seeks to reclaim so-called natural sovereignty by renouncing their legal personality and (often violently) resisting law enforcement or engaging in terrorism. Many so-called sovereign citizens retain the anti-Semitic and racist beliefs of the movement’s Posse Comitatus and Christian Identity origins, while their ideas about individual sovereignty have influenced the Oklahoma City bombers, the armed standoff at Cliven Bundy’s ranch in Nevada in 2014, the armed standoff led by Cliven Bundy’s sons, Ammon and Ryan, at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon in 2016, as well as contemporary militias such as the Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters. On the Posse Comitatus, see also Daniel Levitas, The Terrorist Next Door: The Militia Movement and the Radical Right (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2002) and James Coates, Armed and Dangerous: The Rise of the Survivalist Right (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 104–122. For the influence of the sovereign citizen movement on the Bundys, see J.J. MacNab, “Context Matters: The Cliven Bundy Standoff,” Parts 1–3,” Forbes, April 30, 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jjmacnab/2014/04/30/context-matters-the-cliven-bundy-standoff-part-1. The association of firearms and individual sovereignty has made its way into NRA talking points and more mainstream media as well. In the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, Andrew P. Napolitano claimed the “right of the people to keep and bear arms is . . . a hallmark of personal sovereignty,” and Dan Baum wrote in Harper’s Magazine that firearms are “the ultimate emblem of individual sovereignty.” Andrew P. Napolitano, “The Right to Shoot Tyrants, Not Deer,” Washington Times, January 10, 2013, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/jan/10/the-right-to-shoot-tyrants-not-deer/, and Dan Baum, “On Gun Control and the Great American Debate Over Individualism,” Harper’s Magazine, May 17, 2013, https://harpers.org/blog/2013/05/on-gun-control-and-the-great-american-debate-over-individualism. Perhaps the most explicit incorporation of these associations into theology can be found in the Rod of Iron Ministry, also known as the World Peace and Unification Sanctuary, founded by pastor Hyung Jin Moon, the son of Rev. Sun Myung Moon. Pastor Moon has made individual sovereignty—represented by crowns of bullets and the carrying of AR-15s (a.k.a. the “rod of iron”)—central to the Rod of Iron Ministry’s theology and ceremonies. A Washington Post Magazine story by Tom Dunkel reports Pastor Moon exclaiming “Look at all these crowns of sovereignty!” at the sight of his congregation. “One tenet of the Sanctuary Church,” Dunkel writes, “is that all people are independent kings and queens in God’s Kingdom—a kind of don’t-tread-on-me notion of personal sovereignty.” Tom Dunkel, “Locked and Loaded for the Lord,” Washington Post Magazine, May 21, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/style/wp/2018/05/21/feature/two-sons-of-rev-moon-have-split-from-his-church-and-their-followers-are-armed/. See also Southern Poverty Law Center, “Anti-LGBT Cult Leader Calls on Followers to Purchase Assault Rifles,” February 9, 2018, https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2018/02/09/anti-lgbt-cult-leader-calls-followers-purchase-assault-rifles. ↩

- “The principle of vigilantism,” writes Richard Slotkin, “is the assertion of a privilege of extralegal violence in a social setting where some form of law already exists.” Richard Slotkin, The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization, 1800–1890 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 136. ↩

- For a Foucauldian reading of the sovereign subject as armed citizen, see Jennifer Carlson, “States, Subjects and Sovereign Power: Lessons from Global Gun Cultures,” Theoretical Criminology 18, no. 3 (2013): 335–353. Carlson’s account of why sovereignty has “exceeded the confines of the state” focuses, however, solely on the state’s inability to satisfactorily address high crime rates (345). For excellent analyses of the role gendered experiences of vulnerability play in motivating concealed carry, see Angela Stroud, Good Guys with Guns: The Appeal and Consequences of Concealed Carry (University of North Carolina Press, 2015) and Caroline Light, Stand Your Ground: A History of America’s Love Affair with Lethal Self-Defense (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017). ↩

- Abraham Lincoln publicly ridiculed the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, Lincoln Stephen A. Douglas, for thinking that he “discovered that the right of the white man to breed and flog niggers in Nebraska was popular sovereignty!” Abraham Lincoln, “Portion of a Speech at Edwardsville, Illinois,” in Abraham Lincoln: Political Writings and Speeches, ed. Terence Ball (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 66. For an insightful history of the meaning of popular sovereignty in the United States, see Daniel T. Rodgers, “The People,” in Contested Truths: Keywords in American Politics Since Independence (New York: Basic Books, 1987), 80–111. ↩

- Douglass, “The Kansas-Nebraska Bill,” 330–31. ↩

- Douglass, “The Kansas-Nebraska Bill,” 329. ↩

- Douglass, “The Kansas-Nebraska Bill,” 326. ↩

- Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982), 334. ↩

- Washington Union and Intelligencer, August 19, 1850, cited in Douglass, “The Kansas-Nebraska Bill speech, November, 1854,” 326–327. See also William Goodell, “Different Views of the Constitution and of the Legality of Slavery,” in Slavery and Anti-Slavery; A History of the Great Struggle in Both Hemispheres; With a View of the Slavery Question in the United States, 3rd ed. (New York: William Goodell, 1855), 563–582. ↩

- “The exception appears in its absolute form when a situation in which legal prescriptions can be valid must first be brought about.” Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. George Schwab (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 13. ↩

- Richard Maxwell Brown, The South Carolina Regulators: The Story of the First American Vigilante Movement (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 111. ↩

- J. M. Opal, Avenging the People: Andrew Jackson, the Rule of Law, and the American Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 225. ↩

- Opal, Avenging the People, 225. ↩

- For an analysis of the specifically patriarchal relations of “the sovereign subject (sujet souverain),” see Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2010). For compelling arguments that sovereignty is itself masculinist, see Bonnie Mann, Sovereignty Masculinity: Gender Lessons from the War on Terror (Oxford University Press, 2014) and Wendy Brown, Manhood and Politics: A Feminist Reading in Political Theory (Rowman & Littlefield, 1998). ↩

- Martin R. Delany, “Detroit, Michigan, July 14, 1848,” in Martin R. Delany: A Documentary Reader, ed. Robert S. Levine (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 114–115. ↩

- See Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 203–220. See also Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Doubleday, 2008). ↩

- Hadden, Slave Patrols, 206. ↩

- “The idea of the ‘sovereignty of the people,’” writes historian Richard Maxwell Brown, gives “an ideological and philosophical justification and an awesome dignity to the brutal physical abuse or killing of men.” Richard M. Brown, Strains of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 56. ↩

- Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2009), 178. ↩

- As Simone de Beauvoir writes, “each consciousness seeks to posit itself alone as sovereign subject. Each one tries to accomplish itself by reducing the other to slavery.” Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 52. ↩

- Butler, Frames of War, 178. ↩

- Douglass, “The Kansas-Nebraska Bill,” 330. ↩

- Joseph de Maistre, The Generative Principle of Political Constitutions: Studies on Sovereignty, Religion and Enlightenment (New York: Routledge, 2002), 93. ↩

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, “On the Laws,” in On the Commonwealth and On the Laws, ed. James E. G. Zetzel (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 168. ↩

- Jacques Derrida, “Declarations of Independence,” in Negotiations: Interventions and Interviews, 1971–2001, ed. Elizabeth Rottenberg (Stanford University Press, 2002), 49. See also Edmund S. Morgan, Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988) and Rodgers, “The People.” ↩

- Larry Pratt, “Transfer of Wealth,” News with Views, March 15, 2007, https://www.newswithviews.com/Pratt/larry76.htm. ↩

- Arendt, “What is Freedom?” 164. ↩

- The ideal of freedom, writes Arendt, “became sovereignty, the ideal of a free will, independent from others and eventually prevailing against them.” Arendt, “What is Freedom?” 163. ↩

- Douglass, “The Kansas-Nebraska Bill,” 330. ↩

- Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 234. ↩

- Arendt, “What is Freedom?” 165. ↩

- Alexander Hamilton, “The Federalist No. 15,” in Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist Papers, ed. Ian Shapiro (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 77. ↩

- See Chad Kautzer, “Self-Defensive Subjectivity: The Diagnosis of a Social Pathology,” Philosophy and Social Criticism 40, no. 8 (2014): 743–756. ↩

- Richard Hofstadter, “America as a Gun Culture,” American Heritage 21, no. 6 (1970), https://www.americanheritage.com/content/america-gun-culture. ↩

- See Robert Gooding-Williams, “Fugitive Slave Mentality,” New York Times, March 27, 2012, https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/27/fugitive-slave-mentality/. ↩