In the summer of 2019, a new polemic emerged around the seemingly inexhaustible topic of Islam in France. During a meeting of the summer school held by la France insoumise—a left-wing populist party—the philosopher Henri Peña-Ruiz argued that one had the right to be Islamophobic (“on a le droit d’être islamophobe”).1 Peña-Ruiz subsequently defended this statement, claiming that “it is not racist to attack (s’en prendre) a religion, but it is racist to attack a person because of their religion.” His comments were part of a broader argument about the very nature of racial discrimination itself: racism, he claimed, was discrimination of people for what they are, not for what they believe. Therefore, critiques of Muslims as a group—like critiques of atheists—were permitted, even if one could not reject individuals because of their faith. Unlike homophobia, he argued, Islamophobia does not target people for an essential element of their identity but represents a legitimate critique of a corpus of ideas. If it may seem shocking for a leftist to uphold Islamophobia not only as permissible, but as a right which must be defended, understanding this statement requires a longer reflection on the intersection of racial and religious categories in France.

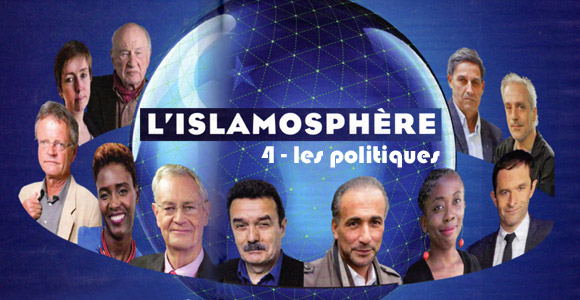

The image of a planetary network of people immediately brings to mind the global conspiracy once attributed to Jews. As Sandrine Sanos has written, “both Jews and Muslims have, in different ways, been “saturated” by an embodied identity from which republicanism demanded they must free themselves.”2 Moreover, in the leftist imaginary, revolution and emancipation are necessarily secular. Peña-Ruiz’s argument, which constructs a strict partition between race (as skin color or appearance) and religion (as personal belief or theology), effectively forecloses any dialogue on anti-Muslim discrimination that borrows from the tools of anti-Black racism. Similarly, the discourse on “Islamo-gauchisme” (awkwardly translated as “Islamic-Leftism”) has become a common insult wielded against those on the left whose allegedly pro-Islamic sympathies, evident in their critique of Islamophobia, make them the unlikely bedfellow of terrorists. Once again, (legitimate) anti-racist commitments are assumed to occupy a different analytical space from discussions on the place of Muslims in the French Republic.3

In the United States, a particular anti-racist commitment rooted in ontological approaches to race also highlights the political dangers of placing discussions of Islamophobia alongside anti-Black racism. Scholars who espouse Afropessimist approaches, such as Frank B. Wilderson III, view Blackness as coterminous with slavery and social death, arguing that anti-Blackness cannot be analogous to other forms of racism. By defining Blackness as a transhistorical ontology, they also locate this particular form of racism outside historical time since “one cannot know a plentitude of Blackness distinct from Slaveness.”4 Stated differently, the hope for the restoration of native land—present in the emancipatory horizons of current-day Palestinians, colonized Algerians, as well as other postcolonial subjects—are necessarily foreclosed to the Slave. The “ruse of analogy,” Wilderson writes, “erroneously locates Blacks in the world.”5 This framework makes a distinction between anti-Blackness and anti-Black racism; while it acknowledges that racisms can be compared, it views anti-Blackness as a singular phenomenon that has structured the modern world and that is, unlike other forms of discrimination, based on an ontological difference rather than the drive to exploitation. Thus, even revolutionary subjects like Palestinians are complicit with anti-Blackness in that their humanity depends on black suffering.6 In addition to eliding the historical links between anti-colonial revolution and anti-racist struggle, this analytical approach also risks positing Muslim Arabs and Black Africans as “incommensurate ontologies.”7

In both the French and American cases, historical circumstances have conditioned a specific reluctance to thinking about anti-Black and anti-Muslim racial projects together. In the US, the experience of chattel slavery remains the paradigm for understanding the dehumanizing effects of racism. In France, on the other hand, postwar attempts to erase the lexicon of race have led to the adoption of a Republican color-blindness. Both approaches raise deeper questions: Is it possible to consider Islam as the basis of a racial project, or has it merely operated as a marker of personal belief? When we speak of Blackness, are we referencing an epistemology that structured racial binaries? Or should the concept be reserved for the bodies that have been defined as Black by dominant schemes of racial classification?

My point in this article is not to call for comparison or to determine a hierarchy of suffering, but rather to think relationally about how anti-Muslim racism was “tied to extra- and trans-territorial conceptions and expressions” that “circulate[d] in wider circles of meaning and practice.”8 Colonial officials drafted techniques of rule based on an international circulation of ideas about racial difference and governance. Structures of anti-Black racism were articulated alongside (and sometimes against) anti-Muslim racism. The French colonial army, for example, often contrasted the docile African to the savage Arab. The years following decolonization, which in many ways signified a global struggle for racial equality, saw creative borrowings of racial categories and anti-racist strategies; Asian youth movements in Britain adopted Blackness as a political identity in the 1970s and 1980s, for example.9 While it may be jarring for French Republicans to accept that discrimination against Muslims, much like anti-Semitism, should occupy the terrain of anti-racist struggle, Algeria’s colonial history demonstrates how Islam exceeded the frame of personal conviction and formed the basis of a political and economic project. If analogizing American discussions centered on chattel slavery risks universalizing a geographically-specific understanding of race and racism, this article seeks to elucidate shifting ways Blackness has been understood and lived outside of the United States.

French Republican colorblindness and American investments in Blackness as a transhistorical ontology both foreclose the possibility of thinking historically about how anti-Muslim racism might be elucidated by studies of Blackness. In contrast, this article argues for a recovery of a more capacious, and indeed relational, understanding of Blackness by analyzing the “racial regime of religion” constructed in French Algeria and revisiting the work of Frantz Fanon.10 When scholars in the US invoke Fanon’s writings to establish the “absolute dereliction” of Blackness, they insist on an analytic divide between the native and the Slave. Yet Fanon’s work borrowed from his experience of anti-black (epidermal) racism in France as he theorized the Manichean system of settler colonialism in Algeria, where the French state did not treat Islam as a question of individual faith or belief. Instead, religion formed the basis of the exclusionary legal, social, and economic binary of settler colonialism. Both as a lived experience and a mode of governance, meanings of Blackness varied dramatically as they circulated among Martinique, mainland France, Algeria, and the United States. Stretching these reflections even further, this article suggests that thinking about how racial binaries structure political projects based on religion helps shed new light on questions of sectarianism and personal status laws in the Middle East.

***

It may seem counterintuitive to argue that anti-Muslim discrimination constituted a racial project in French Algeria. Yet much like anti-Semitism, the line between religion and race is more porous than the secularizing myths of colonial modernity suggest. For example, early debates on colonization flirted with the options of exterminating, assimilating, or relocating the native population, invoking comparisons between the Arabs of Algeria and the indigenous populations of the United States. The physician Eugène Bodichon argued that native Algerians would experience “self-genocide” upon contact with European.11 In contrast, the Arabophiles who surrounded Napoleon III dreamed that the noble features of the Arab race would complement France’s technical prowess and create an “Arab Kingdom.” In 1870, the Third Republic reasserted a civilizing mission claiming that the progress of native subjects would occur through their adoption of French cultural mores rather than evolution within their own cultural milieu. This albeit rough sketch of the different modalities of race-thinking highlights the shortcomings of speaking of a blanket “racialization” of the Muslim population, even within one particular colonial territory. Instead, it is imperative that we account for the specific ways that racial characteristics were imparted on Muslim bodies at particular moments.

While Islam became a marker of absolute difference in the late nineteenth century, earlier histories of slavery under the Ottoman Empire point to how religion, as well as anti-Blackness, were central to the distinction between free and enslaved peoples. In the context of the Atlantic world, Blackness was synonymous with slavery as the condition of “social death,” a status that Orlando Patterson defines by gratuitous violence, natal alienation, and general dishonor.12 Unlike Wilderson, Patterson uses this notion to describe common features of various systems of bondage rather than associating it narrowly with skin color. Yet the distinctiveness of Mediterranean slavery have led some historians to argue that this term does not capture the status of enslaved populations in North Africa.13 Moreover, even scholars in the Black radical tradition such as Cedric Robinson reject that slavery in the Mediterranean established a singular link between Blackness and enslavement.14 In North Africa, corsairs engaged in so-called “white” slavery that targeted Europeans for economic and military motives while relying on a discourse of religious difference.15 Christian boys, often from the Balkans, were enslaved and formed an elite corps of janissaries after conversion to Islam. Other enslaved Christians worked in the grueling domains of construction and sometimes rowed the corsair galleys. These forms of bondage existed alongside the trans-Saharan slave trade, making the question of whether Blackness was synonymous with enslavement a heated debate among historians of the region.16 These arguments in no way deny the existence of anti-Black racism in pre-colonial North Africa, but rather highlight how skin color was conjugated alongside other factors such as religion, social standing, language, and ethnicity. It is therefore problematic to transpose Wilderson’s understanding of social death—where skin color is synonymous with an ontological absence—to Mediterranean histories of slavery.

The French colonization of Algeria provided a link between the “old” colonies in the Atlantic world, which were based on slavery, and the “Second Empire,” which divided humanity into the categories of citizen and subject.17 In Algeria, it was not skin color that foreclosed access to citizenship (and the attendant economic and legal advantages), but rather religion. According to the 1865 Senatus Consulte, Algerian Muslims and Jews were required to renounce their personal status, which applied religious law (as understood by the French) in order to apply for French citizenship. This exclusion was also based on the conviction that Islamic norms of gender and sexuality—particularly polygamy—were incompatible with the French Civil Code.18 Yet five years later, Algerian Jews were offered citizenship en bloc (except in the Southern territories under military rule), and in 1889, non-French Europeans were offered French citizenship. Berbers, who were often seen as more “civilized” than Arabs in colonial ethnologies, were nevertheless denied citizenship on the basis of Islam.

A racial binary based on religion made Islam the unassimilable object for the French body politic. The legal status of Muslims dictated their access to citizenship, property, and survival.19 They were subjected to a number of legal and economic exclusions ranging from the indigenous code of 1881, which outlined a number of infractions that were only punishable when committed by Muslims, to the so-called “Arab tax” through which the natives disproportionately financed their own occupation. It is important to reiterate that being Muslim was not a question of individual belief or religious practice—and even conversion to Christianity did not attenuate the effects of these legal structures. This suggests that discrimination against Muslims was not necessarily, as Peña-Ruiz’s claims, a function of what one believes but rather operated in a similar fashion to racism, which is based on unchangeable physical features (“what one is”).

***

Many works in the canon of theorizing Blackness emerged from the multiple iterations of the color line debated by both colonized and black intellectuals during decolonization. A prime example of this is found in the work of Frantz Fanon, the philosopher, psychiatrist, and anti-colonial militant from Martinique who wrote about his experience of racism in France before departing for Algeria, where he ultimately supported the FLN (National Liberation Front) and became a key ambassador of the Algerian revolution in sub-Saharan Africa. His two most celebrated works, Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth, analyze his experiences as a Black man in France and the struggle against settler colonialism in Algeria, respectively. In the introduction Black Skin, White Masks, he highlights that Blackness in France is experienced differently by Caribbean people and Africans. Unfortunately, this insistence on historical context and the various instantiations of Blackness is obscured by the translation of “l’expérience vécue du noir” as “the fact of blackness ” in English. Borrowing from Jean-Paul Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew, Fanon’s depiction of Blackness is fundamentally relational; even when defined as a lack of ontology, he specifies that this is only the case because of the white gaze (“Le Noir n’a pas de résistance ontologique aux yeux du Blanc”).20

This brief Fanonian detour helps us interrogate how anti-Blackness might be used to study other forms of racism—rather than be partitioned off from colonial structures. It is telling that Fanon notes that when dealing with the police in France, it is worse to be Arab than to be from Martinique.21 Another example of such an inversion is William Gardner Smith’s 1963 novel The Stone Face, which describes the October 17, 1961 massacre of Algerians based on his firsthand observations. The protagonist, Simeon, is at first puzzled to find that Arabs consider him “white” after his arrival in France. He later comes to realize that “the Algerians are the n*g**** of France.”22 James Baldwin made the same observation after his time in France.23 In these accounts, Blackness is depicted as historically contingent and necessarily relational, something that confirms Michelle Wright’s observation that the fact of being black “cannot be located on the body because of the diversity of bodies that claim Blackness.”24 Indeed, there are important continuities in Fanon’s two best-known works, despite their different objects of analysis. In detailing the binary aspects of the colonial world in The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon refers the reader back to Black Skin, White Masks in a footnote, telling us that he has already explained the “mechanism of this Manichean world.”25

At the end of his life, Fanon opted for Algerian nationality, distancing himself from his native Martinique. While sympathetic to the Négritude moment that was in part founded by his former teacher Aimé Césaire, he ultimately disagreed with its commitment to a preexisting black essence. Instead, he adopted Algeria as a homeland, a country whose national identity was based on an Arabo-Islamic culture rather than Blackness. For Fanon, the difference between the two colonial territories was political: while leaders in Martinique, including Césaire, supported postwar reforms that granted the old colonies the status of French departments, Algerian nationalists had waged a violent war of decolonization against any vestiges of French influence. During his time in North Africa, Fanon pressed for a continental and political (rather than narrowly racial) articulation of pan-Africanism, challenging leaders who he saw as too accommodating to France.26 His personal trajectory thus suggests that he saw Blackness as a space of political struggle against various forms of European racisms, including settler colonialism, rather than a transhistorical paradigm based on slavery. In this regards, Fanon’s engagement with African and metropolitan realities made it impossible to define Blackness only in relationship to the historical experience of bondage. In contrast, Wilderson argues that “even as Settlers began to wipe Indians out, they were building an interpretive community with ‘Savages’ the likes of which Masters were not building with slaves.”27 Like Native Americans, Algerians were clearly colonized and not enslaved—an important historical difference. Yet Fanon’s writings, which combine insights as to the functioning of racial formations in the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa, can also be read as a warning against the temptation to straightjacket the multiple meanings of Blackness in the singular experience of chattel slavery.

After independence, a number of Algerian intellectuals criticized Fanon for his elision of Algeria’s Arabo-Islamic culture and his debt to Western thought.28 The Algerian nation state, echoing colonialism’s racialization of religion, insisted that Islam was an indelible marker of Algerian identity that was not reducible to religious belief. As the Tripoli Congress of May 1962 stated, “Islam, stripped of all the excrescences and superstitions that have smothered or corrupted it, is to find expression in two essential factors in addition to religion as such: culture and identity.” The nationality law of 1963 once again made Muslim personal status the crux of national belonging. It stipulated that only those whose father and paternal grandfather came under the jurisdiction of Muslim personal status could become citizens. Europeans who had lived in Algeria for generations were forced to apply for citizenship on a case by case basis.

***

The need to create a unitary national identity in Algeria after 1962 refashioned the meaning of Islam as well as indigeneity. The regime tended to view Berbers, who inhabited the region before the Arab conquest, as a linguistic and ethnic force of separatism.29 In the 1960s and 1970s, Algeria adopted the mantle of Pan-Arabism as well as Pan-Africanism, a stance that sometimes led to tensions between African identity, which was often synonymous with Blackness, and its positioning in North Africa, which looked to the Middle East. Algeria used its international fame as the “Mecca of Revolutions” to address questions of anti-Blackness internationally despite the region’s uneasy history of slavery. This was epitomized when the 1969 Pan-African Festival, held in Algiers, brought together radicals from around the world—including Miriam Makeba from South Africa (who eventually took Algerian nationality) and Eldridge Cleaver from the United States—in Algiers. In her performance, Makeba sung in Arabic, proclaiming, “I am free in Algeria” (ana hurra fil-djazayir) while also noting also that “the time of slavery is over” (intaha ‘asru al-‘abid).

Miriam Makeba Singing at the Pan-African Festival in Algiers, 1969. “Miriam Makeba chante en Algérien,” posted by Mabrouk Ali, July 22, 2018.

Eldridge Cleaver fielding questions from Algerians in the 1970 documentary, Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther, 1:10:29.

Yet despite this revolutionary past, and the Algerian government’s attempts to position the country as a leader on the African continent in recent years, there is no doubt that anti-Black racism is rampant in the country. This was most recently evidenced around the denigration of Khadija Ben Hamo, who was crowned Miss Algeria in 2019.

The long-standing notion that darker North Africans are part of a “diaspora” of slaves, rather than fully North Africa, has fed an uptake in anti-Black racism that accompanied the refugee crisis and the rise in sub-Saharan immigrants.30 The fact that anti-Black racism exists in a country that once used anti-racism as a stamp of international revolutionary legitimacy should not lead us to conclude that this form of violence is timeless or irrational. Instead, it should compel us to interrogate the shifting and even contradictory operations of race in the post-colony.31

The ways in which religious divisions structured imperial belonging played a key role in the subsequent construction of nation-states, which tended to incorporate (or suppress) religious, ethnic, and/or linguistic distinctions in the service of consolidating a national identity.32 Thinking about the intersection of racial and religious categories also allows us to revisit discussions on sectarianism, which Ussama Makdisi describes as “the deployment of religious heritage as a primary marker of modern political identity.”33 To the extent that the designation of sects has become a “technology of recognition,” religious belongings became a matter of state governance in the Middle East.34 This has led certain groups—such as Maronite Catholics in Lebanon—to transform their Christian identity into “a racialized worldview,” as Ghassan Hage has argued.35 In India, the British transformed the existing caste system into a rigid set of categories that overlapped with physical markers as well as religious hierarchies. Rather than taking for granted the partitioning of ethnicity and religion from race, we might follow the shifting bases used by empires to interpellate their subjects and revisit the criteria on which they determined sameness or difference. Postcolonial sectarianism might therefore be read as an afterlife of the regimes of religion constructed by empire rather than a trace of anachronistic modes of belonging. Instead of an analytical certainty, the tendency to posit a stark divide between race and religion should be seen as part and parcel of the secularizing myths of modernity. In discarding the commonly-held assumption that religion merely signifies transcendental concerns, we can instead turn our attention to how it was used as a form of statecraft that assigned bodies with meanings and structured access to political, economic, and social capital. In many cases, such as the French empire, this process occurred in relation to the maintenance of anti-Black structures. Techniques of objectification, understandings of racial hierarchies, and even vocabularies of dehumanization circulated among imperial territories, so that without posing an equivalence, we can view the establishment of racial regimes of religion alongside the drive to objectify Black bodies. Rather than representing incommensurable forms of oppression, both forms of racism generated common strategies of objectification as well as shared imaginaries of liberation.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Sandrine Sanos and Marc Matera for their feedback on this piece.

Notes

- Jacques Pezet, “Qu’a dit Henri Peña-Ruiz sur « le droit d’être islamophobe » lors de l’université d’été de la France insoumise?” Liberation, August 26, 2019, https://www.liberation.fr/checknews/2019/08/26/qu-a-dit-henri-pena-ruiz-sur-le-droit-d-etre-islamophobe-lors-de-l-universite-d-ete-de-la-france-ins_1747363. ↩

- Sandrine Sanos, “The Sex and Race of Satire: Charlie Hebdo and the Politics of Representation in Contemporary France,” Jewish History, 32 (2018): 36–37. ↩

- Muriam Haleh Davis, “Racial Capitalism and the Campaign against “Islamo-Gauchisme” in France.” Jadaliyya, August 14, 2018, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/37858/Racial-Capitalism-and-the-Campaign-Against-“Islamo-Gauchisme”-in-France. ↩

- Frank B. Wilderson, Afropessimism (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2020), 217. ↩

- Frank B. Wilderson, Red, White and Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 37. ↩

- Wilderson, Afropessimism, 15. ↩

- Frank B. Wilderson, introduction to Afro-Pessimism: An Introduction, ed. Frank B. Wilderson (Minneapolis: racked & dispatched, 2017), 12. ↩

- David Theo Goldberg, “Racial Comparisons, Relational Racisms: Some Thoughts on Method,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32, no. 7 (2009): 1273. ↩

- Anandi Ramamurthy, Black Star: Britain’s Asian Youth Movements (London: Pluto Press, 2013). ↩

- I expand on this term in my book manuscript on racial capitalism in Algeria, forthcoming with Duke University Press. ↩

- Benjamin Brower, “Rethinking Abolition in Algeria. Slavery and the ‘Indigenous Question.” Cahiers d’études africaines 3, no. 195 (2009): 805–828. ↩

- Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1982). ↩

- Gillian Weiss, Captives and Corsaires: France and Slavery in the Early Modern Mediterranean (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011), 20. ↩

- Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983; repr., Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 16. ↩

- Another instance of race and slavery that deserved renewed attention is the Arabian Peninsula. See Faisal Abu Al-Hasan, “Al- ʿansuriyya wa tārīkh tijāra al-rizq fī shebah al-jazīra al-arabīya,” available online at https://thmanyah.com/5758, accessed on 8 September 2020. ↩

- Yacine Daddi Addoun has claimed that bondage in Ottoman Algeria did not necessary follow racial logics. Yacine Daddi Addoun, “Abolition de l’esclavage en Algérie: 1816–1871” (PhD diss., York University, 2010), 253. ↩

- Jennifer E. Sessions, By Sword and Plow, France and the Conquest of Algeria (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011). ↩

- Judith Surkis, Sex, Law, and Sovereignty in French Algeria, 1830–1930 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019). ↩

- Despite the colonial state’s convictions that Berbers were ethnically distinct from Arabs, they, too, were excluded from French citizenship based on Islam. Muslim Algerians did not receive French citizenship until 1958. ↩

- Frantz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1952), 89. ↩

- Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs, 73. ↩

- William Gardner Smith, The Stone Face: A Novel (1963; repr. Chatham, NJ: Chatham Bookseller, 1975), 105. ↩

- James Baldwin, “The Black Scholar Interview: James Baldwin,” The Black Scholar 4, no. 4 (December 1973–January 1974): 39. ↩

- Michelle M. Wright, Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 3. ↩

- Frantz Fanon, Les damnés de la terre (1961; repr. Paris: La Découverte, 2002), 44. ↩

- See Fanon’s “The Stooges of Imperialism,” which is directed at the African leaders who supported the French Community, a French proposal to African colonies for political association. Alienation and Freedom. Frantz Fanon, Alienation and Freedom, trans. Steven Corcoran, ed. Robert J. Young and Jean Khalfa (London: Bloomsbury Academic 2018), 661–66. ↩

- Wilderson, Red, White & Black, 46. ↩

- Mohamed El-Milli, “Fanon wa al-Fikra al-Gharbiya,” Thaqāfa 1 (March 1971): 10–25. Abdelkader Dheghloul, “Frantz Fanon: L’ambiguité d’une idéologie tiers-mondiste” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Paris 5 University, 1971). ↩

- Berber identity has continued to be contentious during the ongoing Hirak movement in Algeria. ↩

- Hisham Aïdi, “National Identity in the Afro-Arab Periphery: Ethnicity, Indigeneity and (anti)Racism Morocco,” POMEPS 40 (June 2020). ↩

- Muriam Haleh Davis, “Race and Decolonization in the Maghreb,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, forthcoming. https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory. ↩

- Under the Ottoman millet system, Greeks were defined by religion rather than nationality or language. As a result, Greek Muslims were defined as Turks during the population exchange of 1923. Benjamin Thomas White, The Emergence of Minorities in the Middle East: The Politics of Community in French Mandate Syria (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), 27. ↩

- Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 7. ↩

- Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism; Maya Mikdashi, “Sex and Sectarianism: The Legal Architecture of Lebanese Citizenship,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 34, no. 2 (2014). ↩

- Ghassan Hage, “White Self-racialization as Identity Fetishism: Capitalism and the Experience of Colonial Whiteness,” in Racialization: Studies in Theory and Practice, ed. Karim Murji and John Solomos (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). ↩