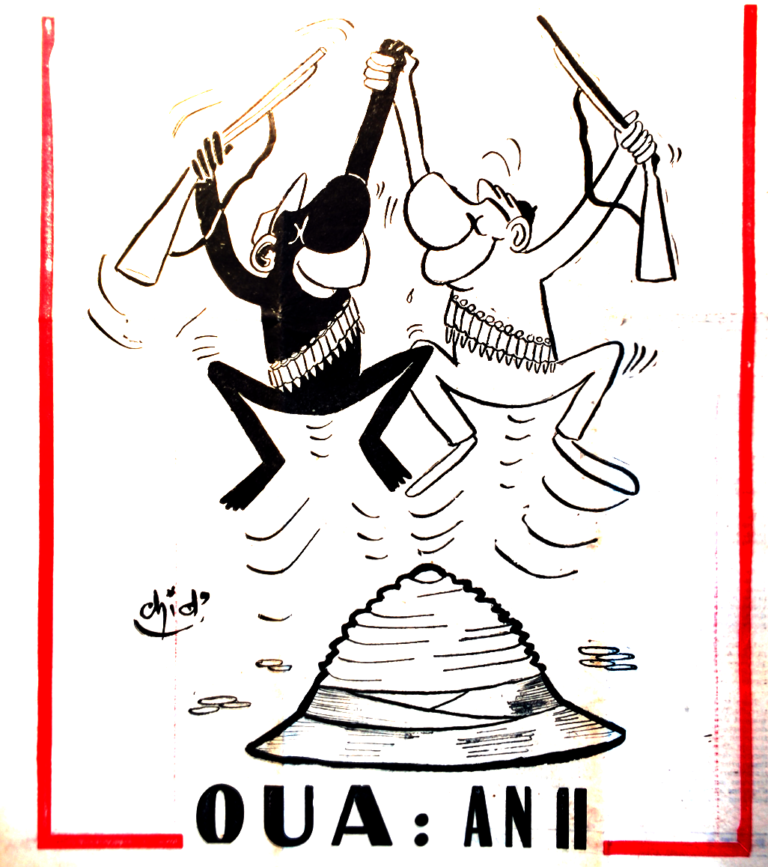

This entry asks what it means to mourn the loss of the state as a vehicle for revolutionary liberation. State power was indeed authoritarian, and global solidarity in the era of the Third World Movement of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s was superfluous, but it still meant something to people then and now. Losing it was felt. In this piece, I revisit the 1967 Arab defeat against Israel known as al-Naksa (the resounding setback) within the context of the Third World movement and its influence on global solidarity in the ensuing decades following 1967. I focus on the loss of Egypt’s position as an anti-colonial leader after the 1967 war and subsequent death of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970. Egypt, once a bastion of revolutionary anti-colonial fervor at the nexus of Pan-Arab and Pan-African imaginaries, and a hub of the historic Third World, became radically realigned with the Global North under Anwar Sadat. I argue that the fate of the Egyptians, Palestinians, Arabs, and of anti-colonial global struggle each became unlinked and siloed as individual struggles. It is not just Arabs or Egyptians or Palestinians who were defeated, it was a whole anti-colonial ethos. How do we mourn the loss of the state as a vehicle for liberation, for Palestinians, for Arabs, for Africans, and for the post-colony?

Keyword: Algeria

On Remembering Le premier festival culturel panafricain d’Alger 1969: An Assembled Interview

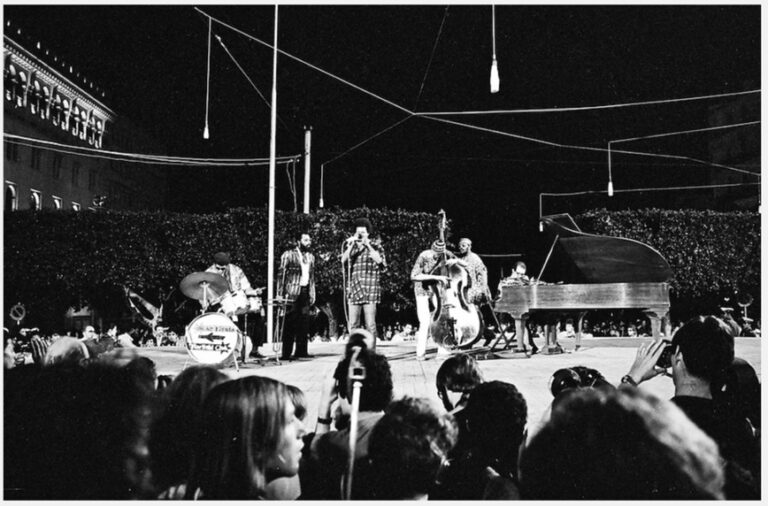

This assembled interview centers both Elaine Mokhtefi and Le premier festival culturel panafricain d’Alger 1969 (PANAF), a festival which she organized and attended as a part of the Algerian Ministry of Information, noting it as an exemplary instance of the power of performance at the nexus of political ideology, activist history, and the subsequent nostalgia for that era of liberation. It is equally an attempt to overcome a distant relationship to each, reflecting on the potential of oral histories to open up new pathways through the past. This history—of entangled international relations negotiated under the guise of a festive performance, a complicated trajectory of global politics which culminated in a remarkable event of celebration and solidarity—remains understudied, a footnote to more “political” concerns of Third World agendas, decolonial reorderings, and capitalist critiques. Yet through Mokhtefi’s testimony, interwoven with searching tendrils of archival detail, we can see that this festival was not a superficial exaltation in extravagance, but a pivotal moment in foreign affairs. More importantly, through her personal history, we can trace the central role that women played in these politics, if often unacknowledged. Edited in 2020, it also counters the pejorative label of non-essential labor applied to most cultural activities during the contemporary pandemic response to COVID-19.

“Incommensurate Ontologies”? Anti-Black Racism and the Question of Islam in French Algeria

In recent years, scholars and activists in France and the United States have questioned whether discrimination against Muslims constitutes a form of racism. In France, some on the left have claimed that religion is a category of belief and therefore should remain separate from discrimination based on skin color or other physical characteristics. In the United States, Afropessimist approaches insist on the specificity of anti-Black racism, rooted in the historical difference between the native and slave. This article, by contrast, argues that race and religion should be studied relationally and highlights how being Muslim exceeded the frame of personal conviction in colonial Algeria, where religious identity was the basis of a political and economic project that were constructed in their wake. The works of Frantz Fanon are particularly instructive in this regard, as he insisted on viewing Blackness as fundamentally relational and also drew on his analysis of anti-Black racism in mainland France to understand the dynamics of settler colonialism in Algeria. The porous line between religious and racial categories also sheds light on discussions of sectarianism in the Middle East more broadly, as colonial regimes irrevocably shaped the contours of the nation-state that were constructed in their wake. Postcolonial sectarianism inherited the intimate relationship between race and religion constructed by empire.