Black popular culture cultivates ideas of futurity and the posthuman that regularly draw on the quotidian experience of Black lives. Through the lens of performance, I examine how artists use embodiment to create speculations of blackness, specifically through the figure of the posthuman that resists, moves beyond, and problematizes ideas about what it means to be human. I closely read the performances of three individuals: comedian and actor Cedric the Entertainer (Cedric Kyles), rapper Missy Elliott (Melissa Elliott), and rapper and model Megan Thee Stallion (Megan Pete). These three performers explore speculative notions of Black life through embodied performance practices. These artists’ movement forms draw from everyday, largely working-class Black experiences that have long been signified as ghetto, ratchet, and hood. Their effectiveness at interrogating Black speculation occurs by pulling overt themes of futurity into their embodied performances, which together deliberate about something beyond the present.

This discussion has two overarching and central points. First, Black popular culture provocatively draws from everyday Black life and performances for ideas about futurist speculations. I extend Mark Dery’s early observation that Afrofuturism “must be sought in unlikely places, constellated from far flung points.”1 Dery’s point here was that Afrofuturism does not have a single focal node but instead can be found in spaces as varied as the examples he gives: the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jimi Hendrix, Lee Scratch Perry, and George Clinton, together with films like Brother from Another Planet (1984) and Born in Flames (1983). I also take inspiration from Kodwo Eshun’s statement that references diversities that point toward Black everyday practices: “It is difficult to conceive of Afrofuturism without a place for sonic process in its vernacular, speculative, and syncopated modes. The daily lifeworld of black vernacular expression [and…] these histories of futures passed must be positioned as a valuable resource [for Afrofuturism].”2 Building on Dery and Eshun’s observations, this discussion explores examples of the various places where Black futures can be produced and enjoyed—within embodied performance practices. Black popular culture’s compelling force, in this regard, is its capacity to draw on a futurity that is often cultivated in “the daily lifeworld” of Black peoples. Second and relatedly, Megan, Missy, and Cedric utilize futurist notions that include both Black humanism and its more subversive counterpart, posthumanism, to reclaim a centrally agentive subjectivity through what are ghetto, ratchet, and hood sensibilities. These performers put forth speculative blackness that refuses the parameters of respectability to express notions of defiance, joy, freedom, sexual desire, and pleasure.

The performances I discuss here have characteristics of both early Afrofuturism scholarship and newer discussions. Initial scholarship focused on, among other topics, how artists and writers work through the racist dichotomy within science fiction that pits Black people as antithetical to progress and technology.3 Within this negotiation, the rearticulated Black subject as an actor of technology often appeared through the figure of the robot, cyborg, alien, or other posthuman that negotiated anti-blackness, capitalist exploitation, slavery, and colonial exercises.4 According to Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E. Jones, a later twenty-first century “Afrofuturism 2.0” has proliferated due to internet practices, social media, and the widespread virtual circulation of cultural production. Afrofuturism 2.0 has used these technologies to rethink a “Black identity [that reflects] counter histories[, …] deep remixability, neurosciences, enhancement and augmentation, gender fluidity, posthuman possibility, [and] the speculative sphere.”5 Missy Elliott’s “She’s a Bitch” music video (1999) and Cedric the Entertainer’s performance from The Original Kings of Comedy (2000) both articulate Afrofuturism 2.0 impulses of seeing futurity through gender and class analyses, while capturing and playing with early themes of computer technologies and space travel. Megan’s 2020 performances following the murder of George Floyd also contribute to this boundary-pushing by incorporating sexual freedoms and pleasure into notions of Black futurity. These three performers exemplify Martine Syms’s discussion of “mundane Afrofuturism,” which resists overly done figures of aliens and space travel and favors “an emotionally true, vernacular reality.”6 Syms argues that mundane Afrofuturism resists racial capitalism partly through the “rituals and inconsistencies of daily life[, which] are compelling, dynamic, and utterly strange.”7 Though Missy and Cedric specifically negotiate the alien and space-traveling figures that Syms seeks to discard, they use everyday Black performances to challenge the stability of these tropes. My objective, hence, is to offer additional considerations to both Afrofuturism scholarship and the performances of these artists by putting embodied performance practices, especially those that are commonplace, as central to analyses. I identify how these reoccurring embodiments of ghetto, ratchet, and hood are not just quotidian but also radical, thereby emphasizing the need to see the common as a subversive site for political intervention.

André Brock (2020) writes about people’s everyday digital cultural practices in “Black Technoculture and/as Afrofuturism,” and demonstrates that Black cyberculture engages in compelling and innovative ideas of speculative politics that embrace the often outcast, disregarded, and unappreciated quotidian expressions of Black life and Black futures. Brock, like Syms, also sees mundanity as ripe for meaning-making. For him, the “mundane digital discourses” of Black Twitter, Instagram, and other platforms theorize about Black futurities by engaging with the “post-present.”8 Black technoculture reconceptualizes the principles of Black cultural survivability through digital mediums, which amounts to futurist articulations and arguably offers a more profound and relevant conception of Afrofuturism than its traditional versions. Brock asserts that well-known examplars of Afrofuturism, such as Sun Ra, George Clinton, Janelle Monáe, Kool Keith, OutKast, DJ Spooky, Octavia Butler, and Samuel Delany, often do not account for the common practices of Black life. Brock’s focus is the less registered versions of futurity that occur within technoculture and that make space for those subjectivities of blackness that are additionally ignored or excluded, like among queer, working-class, and femme people. Brock sees the formal productions of Afrofuturism as expressly intentionalized for audience consumption and different than everyday Black digital practices. Inspired by Brock’s discussion, I contend that Cedric, Megan, and Missy draw on everyday blackness to put forth notions of futurity. Even though their wealth and status at least partly remove them from the day-to-day grind of most people’s lives, their citations are from vernacular Black culture, which charges these performances with meaning.

I locate the everyday performances of hood, ratchet, and ghetto as examples of Black humanism as well as posthumanism. In much of Afrofuturist thought, the posthuman is the figure that rejects the category of the human as defined through white liberal humanism and its relationship to an always-denigrated blackness as opposition to and as a way to determine whiteness.9 Black posthumanism can involve a rejection of Black humanism because of the dead-end notion of the human; consider Kodwo Eshun’s statement, “posthumans [owe] nothing to the human species.”10 Posthuman enunciations reconstruct relationships with machines, which for Black people has been historically burdened. Hershini Bhana Young comments in discussing Afrofuturist artist John Jennings: “Rather than only recognizing that slavery rendered black bodies into units of capitalist exchange and mechanisms of labor, the post-human renders more productive the relationship between human, race, and technology.”11 Through this lens, the posthuman can be the cyborg, the space traveler, the robot, or the alien. Kodwo Eshun describes how the alien emerges from processes of alienation, and thus, Black people might be considered quintessential aliens: “the idea of slavery as an alien abduction […] means that we’ve all been living in an alien-nation since the 18th century.”12

Popular culture has simultaneously embraced a humanism that has asserted Black people as human, rejecting Enlightenment discourse. In “Feenin’: Posthuman Voices in Contemporary Black Popular Music,” Alexander Weheliye examines how the Black voice and its sonorous qualities create notions of the posthuman. Through reading ’90s R&B and its use of the vocoder, he concludes that this music has not abandoned Black humanism. For these reasons, he argues Black humanism and post-humanism in music are not necessarily at odds. “Instead of dispensing with the humanist subject altogether,” Weheliye writes, “these musical formations reframe it to include the subjectivity of those who have had no simple access to its Western, post-Enlightenment formulation, suggesting subjectivities embodied and disembodied, human and posthuman.”13 Though Weheliye finds these two figures in “constant and dynamic tension” in Black music at times, I argue that the performances I analyze for the most part seamlessly intermingle human and posthuman characteristics.14

Black humanism and posthumanism do similar work. The Black posthuman that rejects anti-blackness emerges out of Black humanism, which also defies the same racist legacies. Within popular culture, there is a shared political project that both embark on: to affirm the Black subject. However, I contend that the posthuman, due to its defiance and rejection of what the human is, offers more radical momenta and interventions. Rather than force itself into a category that is built on Black abjection, it forges a new one. The power behind these pieces of cultural production comes when the posthuman puts pressure on and fuses with the energies of Black humanism, and both emergences can simultaneously occur within a singular performance. Performances of ratchetness, hood, and ghetto are examples of the power from both humanism’s affirmation of Black people’s right to self-sufficiency and determination and the posthuman’s rejections of a fraught idea of humanity.

So I depart from André Brock’s contention that quotidian blackness in digital cultures is unconcerned with engaging with notions of the posthuman: “banality and everydayness of Black Twitter, or other spaces where ratchet digital practice is enacted, re-invests futurity into present uses of the digital, rather than in faintly possible Black cyborg or Black magical futures.”15 I expand contemporary definitions of the posthuman and argue that what Brock calls “ratchet digital practice” can contain elements of the posthuman that are fundamental to cultivating radical spaces of freeness. The performances of the posthuman I examine are a part of everyday blackness, and additionally, they are also powerful ways Black people negotiate their way out of exclusion and abjectness.

The posthuman figure not only departs from and challenges white humanism’s creation of blackness, but it also problematizes the neoliberal humanist figure, homo economicus. Here, I draw from Justin Adams Burton, who considers how free market economics shape ideas of humanity by structuring the human and the human’s worth through their relationship to work and readiness and willingness to labor productively. In Posthuman Rap, Burton examines hip hop subgenres like trap and crunk and understands that while both may engage with labor and economies, these musics offer departures from the neoliberal self as bound to defining the human through notions of work. Of the rap duo Rae Sremmurd, Burton writes, “partying in their queer club, refusing to produce and reproduce, to work the way they’re supposed to, [they] arrive at an antireproductive postwork futurity.”16 Pulling Burton and Brock into conversation with each other, I read embodiments of ratchet and ghetto and other everyday performances of blackness—that are often read as nonproductive and thus lacking value—as examples of posthumanism rooted in a radical blackness and futurist politics, even while they contain Black humanist qualities.

Missy, Megan, and Cedric defy neoliberal constructions of the human, and they also, relatively speaking, benefit from the same economic system they critique. Each has acquired wealth throughout their careers and has, at least in part, beneficial relationships with corporate machines.17 Missy has a net worth of 50 million USD, Megan 14 million, and Cedric 25 million.18 Therefore, while each artist’s work reveals an understanding of Black cultural and communal spaces, most likely and at least partly informed by the majority Black lower-working-class settings from which they come, this should not overshadow their present wealth and their relationships to capitalism.19 Their privileged location within commercial culture reminds us that Black popular culture can offer critical yet complicated spaces of interrogation.

More Brilliant than the Moon

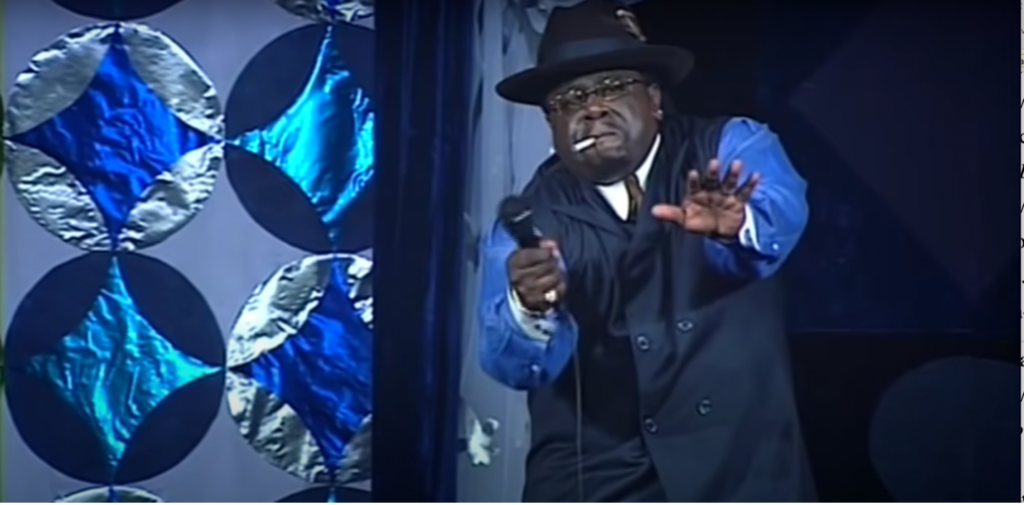

The Spike Lee-directed The Original Kings of Comedy featured Cedric the Entertainer alongside comedians Steve Harvey, D. L. Hughley, and Bernie Mac.20 In 2001, it received nominations for an NAACP Image Award and the Chicago Film Critics Association Award, and inspired spin-offs like The Queens of Comedy and The Original Latin Kings of Comedy. During the live performances recorded and played in movie theaters across the country, every element of Black life was up for grabs, including differences with white people, work habits, intimate relationships, family, and children. At times, the performances included using, quite troublingly, misogynoir, ableism, and queer antagonism as devices for jokes and punchlines.

Most noteworthy was the last two and a half minutes of Cedric the Entertainer’s routine, where he created a setting of speculative moon travel for Black people. Cedric’s performance emerged within a trend beginning from the mid-1990s and extending to the early 2000s, where a series of films highlighted Black people as central in futurist, alien, and otherworldly narratives beginning with Space Traders (1994) and its HBO reproduction, Cosmic Slap (1994). As Ytasha Womack notes, films like Independence Day (1996), Men in Black (1997), Enemy of the State (1998), The Blade Trilogy (1998, 2002, 2004), and The Matrix (1999) all additionally contributed to this trend.21 In 2024, actor and comedian Katt Williams propelled this skit back into the spotlight when he accused Cedric of stealing from his earlier 1998 BET Comic View performance.22 According to an unearthed video, Cedric seems to have used Williams’s skit of riding in a Cadillac convertible to assemble his vision of Black space exploration.23

Cedric begins the skit by acknowledging that Black people might not have the financial wherewithal to manufacture avenues for such a sojourn and proclaims that if white people abandon earth for the moon, “Dammit, we comin’ to the moon!” His production of this scene is indexed by the racist tragedy that white folks “think they just gon’ leave us here on earth,” illustrating an argument that Black people’s opportunities to travel, in this case, are carved out of taking advantage of what white people are easily able to forge. Cedric troubles the notion of white flight. Beginning in the 1950s, white flight to suburbs and exclusive parts of cities defined neighborhoods, schools, and employment opportunities before gentrification became the dominant practice that described the shifting community compositions that impacted Black people. In reality, gentrification has existed in the United States since at least the mid-twentieth century, and white flight continues to this day.24 Within this post-earth setting, Black people will have adapted to a society that continually abandons them, and a Black future, according to Cedric, will still have white people fleeing blackness. Cedric seems to have recognized the direction of space travel. A mere twenty years after his speculations, a “billionaire space race” is in full swing, with Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Richard Branson’s Virgin Group, and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin in competition to develop space tourism using private vessels.25 Since 2020, each of these companies has accelerated ambitions to offer wealthy consumers several options to leave the planet temporarily. To travel on SpaceX’s ship to the International Space Station, a ticket costs 55 million USD; a brief 1.5 hours on Virgin Galactic is 450,000 USD; and Blue Origin’s 10-minute flight to space and back will cost 500,000 USD.26

Cedric’s skit accurately predicts that racial capitalism will seep beyond the borders of the earth’s atmosphere, and he responds by depicting a relatable Black working-class ghettocentric aesthetic to celebrate Black futurity. Challenging the attachments of white wealth to mobility, Cedric proclaims, “We’ll be right behind y’all in spaceships with Cadillac grills!” This line is a sure nod to George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic’s Mothership Connection (1975), where the group used space travel and spaceships to reconfigure slave ship economies into ideas of survival and transcendence. Clinton describes, “I was a big fan of Star Trek, so we did a thing with a pimp sitting in a spaceship shaped like a Cadillac, and we did all these James Brown-type grooves, but with street talk and ghetto slang.”27 George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic’s funk music effectively argued for Black people’s place within space technologies amid a longer tradition that pitted Black embodiment and white technology in opposition. J. Griffith Rollefson writes, “Parliament produces its P-Funk by hyper-amplifying, cloning, and otherwise electronically replicating the funk. […] Furthermore, their profoundly successful engagement with technology and technological discourses of progress helped to destabilize the fallacious dualism of white technology and black soul.”28 Like Clinton, Cedric also uses ghetto sensibilities to join this travel on his own terms. He grabs a stool and sits inside his imaginary spaceship. Tugging his trousers up slightly to ready himself to hit the gas pedal, he turns the key and moves his foot in downward motions to imitate stepping on the gas. This point is where one finds similarities with Katt Williams’s performance. We hear music as an engine turns over in preparation for his travel. With sound technology assisting him, he turns the huge imaginary wheel of his rocket.

Cedric’s performance draws on ideas of the posthuman that resist the ways society disciplines people into obedient workers where wealth and success measure humanity. It should be clear—Cedric can barely afford to fly off to the moon, but he does anyway. He sits back, grooves to music, grins widely, and is in no rush whatsoever: “Nigga just rollin’, one headlight out, tags be all wrong.” As he readies himself on the stool, he sees the rocket through Black perspectives, proclaiming that Black people have no problem driving such a machine because of its similarity to a ’72 Deuce and a Quarter (also known as a Buick Electra). The crowd cheers wildly at this reference as they prepare for his departure. He presents himself as what Burton would describe as the “exception to neoliberal humanism” and is viewed as unworthy of flying because he does not portray himself as an idealized worker. Burton explains that those who fail to be a prototype of marketplace success face “biopolitical consequences,” such as “increased surveillance and detainment; [and] physical removal from things like healthy food, clean water, education, and other resources that can be the difference between poverty and subsistence.”29 Burton’s example here is Black men who are killed by police, as they are “removed from the right to live,” and it is easy to see Cedric’s character through the lens of a similarly undeserving Black figure.30

Perhaps unintentionally, Cedric speaks back against a portion of Steve Harvey’s earlier act and confirms that Black people have a right to access outer space regardless of economic access and societal exclusions. This part of The Original Kings of Comedy is portrayed as an impromptu interaction between Steve and random audience members. Right before the intermission, a group of seemingly cis men sitting in the front row walk out of the arena with Steve asking where they are going and taunting them for leaving. Then he asks the audience to hand him one man’s expensive-looking leather coat and puts it on, which summons cheering and laughter from the audience. After the show resumes, Steve returns to the stage, stating, “Hey, playa, I knew you was gonna come back, hee, hee […] left something [his coat]! Wit’ yo’ cool ass!” Steve calls him a thug and exclaims, “They told me backstage your name Boogie.” Steve asks Boogie what he does for a living, and Boogie states, “computer school.” Steve responds, “Computer school?? Hmmm,” with a mocking side-eye. Steve then says, “Come on now. I asked you what you do for a living, and the answer that popped into your head was computer school. Let me rephrase the question. How do you earn money?” Boogie answers, “computer technology,” with Steve retorting after looking off into the crowd judgmentally, “I know we shouldn’t say this to one another as Black people, but you CAN’T spell motherfucking ‘technology’!” Steve continues, “Know good and hell well your ass ain’t into nothing TECH-NI-CAL. You shouldn’t even judge a book by its cover, but there’s nothing about you that says ‘computer’ or ‘school.’” The back and forth between them continues, with the crowd rolling over in laughter, and finally, Steve ends the section supposedly “outing” Boogie as someone from the streets. The point here is made. Boogie wears baggy pants, sunglasses, and a beanie cap and performs a type of unaffected coolness even when talking to the famous Steve Harvey. For this, Steve leans into a historic trope of Black people as not being innovators within technology, as well as the erroneous neoliberal notion about economically moral uprightness, and turns it into hilarity, refusing to imagine Boogie as a Black man who can express a hood subjectivity and work in the field of technology.

Cedric’s performance resists the confinement that Steve places Boogie in and embodies a Black person with access to space travel technologies. The moment when Cedric admits he has not fixed his busted headlight or renewed his registration tags both challenges neoliberal humanity and reveals the day-to-day lives of many cash-strapped people. Even facing limited resources, he maintains his right to travel to the moon, renouncing the idea of neoliberal personhood through his ongoing proclamations that he will still be space trekking unfazed and styled despite any actual economic barriers.

Cedric the Entertainer’s proffer of a posthuman rejection of homo economicus powerfully sets the foundations for how he affirms his humanness through his elation about his journey. He seizes the right to the category of the human by centering his joy, exemplifying what Alexander Weheliye describes as “denaturalizing the human” while “laying claim to it.”31 Similar to George Clinton’s celebration of ghettocentricity, Cedric displays pleasure as he listens and jams to the 1980 funk song “Cutie Pie,” smokes a cigarette, and honks, smiles, and waves to others on his way to the beyond. His reference to George Clinton and groove to “Cutie Pie” draws on funk music’s otherworldly sonic qualities to create space travel rooted in a Black aesthetic tradition that fits within hood sensibilities. Cedric’s performance and affect perfectly demonstrate what Mark Anthony Neal terms a “post-soul aesthetic.” Neal argues that popular culture in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, including films and music, departed from the rhetoric of civil rights and Black power as they navigated a world of “deindustrialization, desegregation, [and] the globalization of finance communication,” among other forces.32 Neal describes how the often-criticized figures that appear in popular culture, like “the nigga, queer, crackhead, or baby mama,” are fundamental to notions of a Black community and exemplify a “post-soul condition” that thrives on “folk sensibilities.”33 The Original Kings of Comedy was released in 2000, with Cedric aptly embodying the figure of the nigga that Neal describes as someone with a comfortable knowledge of both everyday life and his place within a larger social system, which works to “deconstruct the most negative symbols and stereotypes of black life via the use and distribution of those very same symbols and stereotypes.”34

Cedric’s words, gestures, and smirks illustrate how this Black cultural sensibility can be made humorous through its relatability to everyday life. The Black audiences in the film are shown laughing, shouting in affirmation, nodding their heads, standing up and pointing toward the stage, and participating in other methods of resonating with his story because perhaps they, too, relate to disavowing social and economic violence with a joy-centered freedom. Simone C. Drake and Dwan K. Henderson argue that Black performers defy the notion that they must appeal to white people who buy and support their work, instead stating that “the disruptive trope of blackness in the twenty-first century often weds resistance to pleasure, not for the white audience but for the Black audience in need of catharsis.”35 Cedric’s reliance on hood performativities and US Black linguistic aesthetics effectively excludes white people from being easy consumers of his stage act, as they are instead the hinge upon which the joke is made funny. He digs at white people’s profound truth that too much Black proximity—Black neighborhoods, Black people, blackness—is pervasively undesirable and detestable. Calling out this reality, Cedric exclaims that their travel will not provide the convenient comfort of leaving the tragedies of the earth behind them.

Sighting in the Abyss36

Missy Elliott has had more consistent and explicit Afrofuturist themes in her work compared to Cedric the Entertainer and Megan Thee Stallion.37 The song and music video “She’s a Bitch” dropped in 1999. Years later, Missy performed it in the opening for the 2017 VH1 Hip Hop Honors Awards, which that year highlighted the “game changers” of 1990s hip hop. In 2023, rapper BIA released the song, “I’m that Bitch,” which sampled from “She’s a Bitch” and included the song’s very familiar Timbaland adlibs, as well as sci-fi-inspired costumes, maintaining the song’s longevity and its futurist afterlives. Jasmine A. Moore examines Missy’s music, reminding us that her themes of Afrofuturism are hers but also influenced by director Hype Williams and producer and longtime friend Timbaland. Specifically, Moore focuses on Missy’s use of the monstrous, “the weird,” and the “uncanny” in the music as part of a “visual horror aesthetic [that] operates as a transformative dance with fear to usher in forms of play and pleasure.”38 Moore contends that “She’s a Bitch” exemplifies “reverberative memory,” a process that resists temporal linearity through sonic remixing and visual elements while also referencing past Black women’s musical traditions, which work to elicit powerful Black futures.39 The song centers on her lyrics as a boast rap, a defiant assertion that she rules the hip hop game, and the musical instrumentations are fast paced, simplistic, and repetitive. We hear the recurring announcement, “She’s a Bitch!,” throughout the song. In an interview, Missy discusses how this song is her response to the very real conditions of a music industry whose gatekeepers have been and still are (cisgender) men:

Music is a male-dominated field. Women are not always taken as seriously as we should be, so sometimes we have to put our foot down. To other people that may come across as being a bitch, but it’s just knowing what we want and being confident.40

While her use of props and settings are visually stunning presentations of what the future could look like, Missy’s performance is perhaps more compelling because she relies on everyday performances of blackness to create her speculations. Her performance of the posthuman provides the powerful grounding of her also-compelling Black humanist embodied practices. The video is shot inside a technological setting or an “imagined computer mainframe.”41 She performs defiant, confident posthuman robotic moves, merging blackness and technologies not at odds but in cohesion. Her self-assured robotic style works to serve as her response to the industry’s attack on her humanity. The robot departs from the penultimate speculative figure of the idealized capitalistic laborer, where racialized it contains traces of the slave, and into a usable cultural formation of hip hop blackness. From the 1970s robot dance (and its iterations beyond that period) to Black women adopting machinic qualities in hip hop performances, the figure has been recast as a techno-posthuman celebration of style that rebuffs anti-blackness.42 Missy twists and distorts the body in stiff yet rhythmic and stylistic yet mechanized ways, which acknowledges society’s grip on the Black body and plays with the spaces between freedom and compliance, and between technology and the body. Her performances of the robot, which were and have been part of Black hip hop movement practices, push back against André Brock’s contention that “blackness is neither posthuman nor interested in being so.”43 The robot dance is both posthuman and quotidian, and therefore, Brock’s idea that “posthuman, technophilic Black futures envisioned by Afrofuturist artists and scholars are removed from everyday life” might not apply to Missy’s stage performance.44 The robot, like so many other Black dances, is rooted in the sociality of and interactions within Black everydayness, and a part of Missy’s effectiveness in “She’s a Bitch” is drawing on formations of this engaging blackness.

Missy conjures notions of the posthuman to make herself a purposefully unintelligible and unknowable figure. Her robotic moves conjoin with her fusion of the masculine and feminine. In the video, she struts toward the camera and juts her arms, evoking Black masc gesturing. Other times, she moves and touches herself seductively and ever so slightly, dancing in front of femme dancers dressed in risqué outfits. Elliott Powell’s analysis of Missy Elliott includes what he terms “a musical aesthetics of impropriety,” an organization of sonic characteristics that scrap normative markers entrenched in respectability, decorum, and decency. Seeing Missy as one who holds queer politics in her work, Powell writes that her music exemplifies “Black queer potentiality outside the traditional evidentiary logic of verifiable, hard, and proper proof that often undergird attachments to the politics of recognition.”45 He points out that Missy has yet to comment on her sexuality, thus refusing the moral policing and surveilling by larger society to which Black people remain subject. These dodgy and shifty practices also occur in her embodied gendered performance practices, where she assumes the right to access any available performances of Black genders within hip hop. In the video, Missy often refuses to look straight at the camera, and when she does, it is menacing and protective, again departing from traditional feminine gesturing. At one point, she flips her hair in front of one eye, limiting the viewer from the pleasure of her eye contact and refusing surveillance from the very cameras capturing her music video. Her performances feel very human, bodily, and banal, and additionally evoke posthuman ideas of a fundamental refusal to fold into a disciplined biopolitical subjecthood. Her stances and gestures are expressive practices that long exist within Black communities and are part of a broader everyday set of embodiments that compel us to relinquish a humanity tethered to policing practices rooted in anti-Black racism and move forward a prospect where the blurring of Black (queer) genders can be gestures of survivability and futurity.

In Missy’s video and again in the 2017 performance, blackness is the prioritizing element of the posthuman. In the video, it is her stunning use of Black skin, where she and her dancers, who are all Black, present themselves as darker-skinned, what Jasmine Moore calls “inky blackness.”46 In one of her outfits, Missy appears in black, with large dark lenses covering her eyes. The tops of the lenses are outlined in white diamond-like jewels. In the video, the color white only seems to exist so that viewers can see the use and variations of black. Whiteness exists as the shine of the leather, the glint of the jewels, and the color of her teeth as she displays her defiant facial features and dodgy gazes. Her darkened skin blends into her clothing, which also blends into the checkered black background. Missy walks through her sanitized, shiny, black tunnel while donning a cape that flaps behind her. At times, she struts, dances, and wraps her hand over her head, conjuring Black masculinity and never breaking from her gait through the tunnel. In the 2017 live performance, Missy recreates the video with symmetric backgrounds and dancers, adding stage props like graffitied buildings. Again, Missy and her dancers are as Black as their shiny machinic outfits. Blackness, especially the choice to be blacker, is a defining feature of Missy’s Afrofuture.

I read these aesthetic decisions as posthuman and through Burton’s contention that neoliberal humanism renders “identity politics” obsolete in favor of capital-maximizing logic where all are invited into a fabricated multiracial setting if one conforms to marketplace ideologies. Building from Jared Sexton, Burton notes that neoliberal humanism espouses a post-race multiculturalism, whereby blackness, or “anyone still clinging to a racialized group identity[,] is considered out of step, backwards, antagonistic, racist.”47 Missy’s aesthetic choice to present herself and her dancers as blacker in both performances deserves our attention, especially in a pop culture setting where musicians standardize their music to appeal to broad audiences and Black rappers (and even at times Missy herself) incorporate lighter-skinned, racially ambiguous, and white performers and musicians into their lineup. Here, Missy constructs a compelling and forceful Afrofuture where blacker blackness combines with everyday corporealities.

Missy uses commonplace Black performativities within her rehearsed routines, which fashion a space of informality that works symbolically to divest from disciplining institutions. In the live performance, she recreates a moment in the video where she and her dancers rise out of oceanic water and continue their routine. Though Missy has never stated as such, this water scene invokes Drexciya, a Detroit-based electronic music duo. In their 1997 album, The Quest, the group details how Drexciya is the name of a past sub-Atlantic oceanic place where lived the descendants of pregnant, kidnapped, and sold Africans who were thrown from slave vessels. Drawing on the fact that babies live in amniotic fluid, the story goes that the babies of the discarded had learned to survive underwater and built a society away from the treacheries of the plantation system. Kodwo Eshun notes Drexciya “speculates on the evolutionary code of black subjectivity,” and it is through a frame of survivability that they envisaged this album, as well as a later one, entitled Grava 4 (2002), that laid claim to the right to space travel.48 In the video and performance, Missy and her dancers emerge from the water with costumes with alien-like spikes on their heads. They rise on a huge M-shaped platform as if they had survived subaqueous settings. Importantly, Missy’s dance movements make undersea living an imagined part of quotidian blackness. When they come to the water’s surface, she continues dancing in the same composed, cool, and unperturbed manner. Like in many of her routines, Missy appears to never try too hard when she dances; she moves with just enough energy to give shape to the routine, though her dancers have lively and sharp crispness with their steps. Missy dances with control and style, and her gesturing is recognizable and relatable as she presents this routine as everyday Black movements. She knows the choreography but will only do so much labor. This refusal to work too hard is an instrument of an embodied posthuman Black futurity that conveys a sense of knowing how to survive, knowing how much to give and what to hold onto.

Missy flings the statement “She’s a Bitch!” into her sonic space, only to repeatedly scoff at the insult by pulling it into her track and sucking all the pathologizing force out of it. Her rhythmic and robotic dance moves, which fold effortlessly into gender fluidity, and her refusal to be a locatable subject bring posthumanist qualities to bear with her humanism, producing an almost indistinguishable mix of embodied radical blackness.

Go Get a Late Pass49

Megan Thee Stallion delivered two performances in the wake of the atrocious 2020 viral recording of white police officer Derek Chauvin crushing Black man George Floyd to death: 1) The pre-recorded performance for the BET Awards in July of 2020, and 2) the Saturday Night Live (SNL) show in October 2020.50 In both performances, Megan leverages the visualities and embodiments of futurity and posthumanity. Megan’s performances of ratchet and hood hold both human and posthuman qualities. For the BET performance of “Girls in the Hood” (2020) and “Savage” (featuring Beyoncé) (2020), she presents herself in a dry, postapocalyptic desert landscape that appears dystopic and desiccated, a remarkably familiar scene given our current climate crisis. She and her dancers twerk and throw it back on a rudimentary stage with graffiti art of raised fists and a Black Lives Matter sign in the background. At the end of the video, someone from her crew drives her into the horizon on a futuristic and militaristic vehicle. “Is this the present? Or is this the Afrofuture?,” are questions that plague this performance. As tobias c. van veen notes about Public Enemy’s 1988 intro “Countdown to Armageddon,” where they exclaim “Armageddon been in effect,” meaning “total cultural destruction and dehumanization had already happened,” that is, under the institutions of slavery.51 Nothing is more apocalyptic and world-ending than the human trafficking operation across the Atlantic and the ensuing brutality of slavery. According to van veen’s reads on Public Enemy, we have been living out the “end of the world” for many years now; we are already in a dystopia. Like so many Afrofuturist projections that serve a dual purpose of interrogating and critiquing the present while offering up a reality beyond this one, Megan Thee Stallion’s landscape collides the present and future.

Figures 3 & 4. Screenshots of Megan Thee Stallion in her 2020 BET Awards Performance of “Girls in the Hood” and “Savage” Remix and in her 2020 SNL Performance of “Savage” Remix.

Ratchetness, through embodied booty dancing like twerking and her signature “Aaahhh!,” is an articulation of everyday Black futurity centered on pleasure. While Missy Elliott creates an expressivity that shirks gendered boxes, Megan Thee Stallion uses performances of sexual desire read as explicitly feminine. Her declaration “Aaahhh!” where she sticks her tongue out, subtly tilts her head, and smirks suggestively with one side of her lip slightly raised, is a performance of sexual pleasure. Megan’s vocal utterance with her tongue elicits the sounds of someone supposedly gagging when giving oral sex to a person with external genitals.52 She makes the gesture frequently, including performing on stages and in music videos, posing for pictures, and when approached in public, which makes regular her self-defining right to sexual pleasure as a cis Black woman. She uses the performative utterance flexibly in her raps, and often alongside the declaration “gaggin’,” such as in the intro to the “Savage” remix during the BET performance: “I’m a savage, attitude nasty/ Talk big shit, but my bank account match it/ Hood, but I’m classy, rich, but I’m ratchet/ Haters kept my name in they mouth, now they gaggin’, Aaahhh!” Megan and her dancers transition into a choreographed dance that includes seductive glances toward the camera while rhythmically shaking their booties and thighs.

Like Missy Elliott and Cedric the Entertainer, the core of Megan’s speculative pronouncement is her embodied performance practices. L. H. Stalling moves us toward thinking about ratchetness as a futurist practice, though she stops short of naming futurity or Afrofuturism.53 In analyzing the role that hip hop strip club culture plays in queer desire and anti-respectability politics, Stallings fits Black ratchetness into Robin D. G. Kelley’s Freedom Dreams, quoting this line from his work, “Surrealism recognizes that any revolution must begin with thought, with how we imagine a New World.”54 To imagine something different, Stallings notes that Black strip club culture both “undoes” and “creates new performances” of genders and sexualities, thereby enabling participants to divert from the ways society orders Black bodies.55

Ratchetness and twerking exist within the spectacular and the quotidian, the human and the posthuman. While these expressivities are given a platform within commercial hip hop culture, they are a part of the ordinary and everyday practices that many Black femmes, trans and cis women, and trans and cis girls employ to celebrate joy, agency, and freeness. Kyra Gaunt informs us that twerking originated from New Orleans hip hop scenes, and since it spread around the country and globe, Black girls (and those of other races) have taken to the internet to display their skills. Specifically, Gaunt explores “the bedroom culture of YouTube twerking and strip club p-popping” where “twerkers back that thang up into the webcam.”56 Gaunt’s discussion is similar to Jasmine Johnson’s, who calls these movements “flesh dances,” ones that blur “the boundaries between sex and dance and between public and private acts.”57 Since Gaunt’s study, we can include platforms like Instagram and TikTok, where trans and cis girls and other queer Black performers capture and circulate their skills. Gaunt and Johnson’s conversations encourage us to think about dances in homes, on sidewalks and blocks, and in dance clubs that are not always captured by recording devices.

Many scholars discuss ratchetness and twerking in the context of a salvaged and rearticulated humanity. Aria S. Halliday argues that twerking is an intimate, pleasurable act that allows participants an awareness of the self and the world around them. “The act of Black girls collectively twerking, as a cipher in multiplicitous gyrations and gluteal muscle isolations, becomes an avenue to know the world from one’s own body, to know who you are, because of how your body moves.”58 Gaunt, as well as Halliday, regards the twerk as one of many US examples existing within a long tradition of similar Afrodiasporic dances that is an intentional and skilled practice and “a complex spectrum of stylized and rhythmically-timed gestures.”59 More expansively, Bettina Love explores how working-class Black queer youth deploy ratchetness in their everyday lives to address precarity, silence, and marginalization. Love writes that ratchetness is a lens or “methodological perspective that recognizes and affirms the full humanity of Black queer youth for their sexual desires, multiple identities, economic status, style of dress, language, [etc.].”60 The humanness that Halliday and Love encourage us to acknowledge through ratchetness and the twerk is a recaptured one, occurring when people turn away from the forces that define notions of humanity through narrow registers of whiteness. Twerking is an embodied practice that exists within a long history of diasporic expressiveness, a sophisticated cultural method of producing meaning, and a process of calling attention to the category of the human through its fleshy, seemingly confrontational, sensual Black style.

Ratchetness and twerking, while rooted in notions of Black humanity, harness fundamental elements of the posthuman to forecast Black futures. As we see with Cedric’s masculine hood performativities, ratchetness is “the performance of the failure to be respectable,” according to Stallings.61 To build on Stallings, Black respectability politics do not just prostrate to a whiteness paradigm but also to a neoliberal insistency that one’s body must be productive in service of seemingly common-sense neoliberal logic. The refusal to be respectably Black and thus respectably biologically reproductive and respectably neoliberally productive opens a space where Black people articulate pleasure and joy as a way of imagining another present and future through creating a dissociated humanity via posthumanist embodied gestures. The term twerk comes from “to work” or “to werk,” and even though the dance is really about workin’ that thang or workin’ that dick more specifically, it is also a set of movement forms that exist within a society where laboring is the most important thing a person can do.62 Therefore, twerking exists in broad reference to and within the concept of what it means to work and how that work is tied to and extends from heteropatriarchy. As he does Rae Sremmurd’s trap and crunk convergence, Burton might call twerking a type of “postwork.” He contends, “The rap duo turn the club into a posthuman vestibule, a space that reconfigures work so that it operates, as [Sylvia] Wynter envisions, outside of dominant ideas of what it is to be human.”63 Though I do not think it is entirely possible for the duo’s club scene to “[vibrate] queerly out of earshot of neoliberal humanism,” as Burton notes, this analysis does lay bare how artists use their bodies to resist conscriptions in favor of pleasure and leisure.64 Megan’s ratchet embodiments similarly hold queer features. From performing at the 2023 LA Pride in the Park music festival to rapping about her attraction to (cis) women and sexually scissoring with Cardi B in performances, Megan has affirmed that her ratchet embodiments can be queered.65 André Brock cautions that the posthuman within Afrofuturist productions is restrictive, not allowing for movement outside of respectability paradigms: It is “an embodiment that Blackness is denied via hyper-visibility, hyper-sexuality, and deviant morality.”66 However, Megan moves against this fixity and generates a corporeality rooted in the celebration and public display of sexual pleasure as a basis for her musical interventions and, in so doing, pushes back against the figure of the laboring, productive body.

Megan Thee Stallion’s twerk politics and a present-future dystopic setting are, therefore, not strikingly disparate. Instead, both the performances of ratchetness and dried-up futures help to tell a common narrative of Black permanence that withstands campaigns of violence, whether social, economic, or environmental. Megan’s performance is compelling and generative because it is situated within the everyday lives of Black femmes, queer people, women and girls, and anyone else who might twerk, shoring up the ways that many express their bodies in willful defiance of the disciplinary regimes that act in their lives.

In her SNL performance, Megan echoes refrains from Black Lives Matter activists who steadfastly reject calls from all corners of US society to protest police violence in palatable and receptive ways that cater to white people’s feelings and comfort.67 The SNL setting for her humanist and posthumanist embodiments differed significantly from the desert landscape of the BET Awards, as the SNL stage backdrop included techno-abstract black and white symmetrical moving shapes that gave futuristic vibes, which also matched the outfits of Megan and her dancers. Megan used this stage and song to frame a conversation about the need to protect Black women by using the story of Breonna Taylor and, in so doing, argued that Black people are owed humanity. To set this scene, in September of 2020, Kentucky’s then-Attorney General Daniel Cameron orchestrated what appeared to be a sham hearing about whether to prosecute the officers who shot Breonna Taylor in her sleep during a no-knock raid at the wrong house earlier that year in March.68 Interrupting the performance halfway in are the sound of gunshots and the sight of bullet holes in the background that tear away at the abstract shapes coursing through the setting in much the same way bullets tore into and through Breonna Taylor’s body. We then hear excerpts from Malcolm X’s famous 1962 speech at the funeral service of Ronald Stokes, whom the LAPD killed, as well as activist Tamika Mallory’s September 2020 affirmative avowal that Daniel Cameron “is no different than the sellout negros who sold us into slavery.” The bullet holes appear on the screen behind the performers as they stand readied and still. Malcolm X’s words include, “the most disrespected […], unprotected […], neglected […] person in America is the Black woman”; “Who taught you to hate the texture of your hair, the color of your skin […], the shape of your nose?”; “Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your hair to the soles of your feet?” After this, it transitions into Mallory’s proclamation. As these words audibly interrupt the music and dancing, Megan and the other performers stop dancing and face the crowd, putting their fists up repeatedly in punch-like motions. “SAVAGE” appears on the backdrops, and blood flows from the bullet holes behind them.

Megan Thee Stallion is a victim of violence herself, as rapper Tory Lanez shot her in the foot after a party in July 2020, just a few days after her BET performance and a few months before her SNL performance. The iniquitous misogynoirist criticism she received online after the incident marked her body as ungrievable and unworthy, as Nikki Lane notes in her appropriately titled piece “Ratchet Black Lives Matter,” serving yet another reminder that Black people, and in this case, women, are not afforded humanity.69 Megan was likely healing from her bullet wounds as she delivered this SNL performance.

Megan’s corporeal twerk serves as a response to violence done against Black women. Before I firm up this point, it is critical to point out that the word “SAVAGE,” and not “RATCHET,” appears between Malcolm X’s and Mallory’s words, a statement of how Megan perhaps perceives the limits of ratchetness in activism. We cannot overlook how the song and much of Black vernacular has recast “savage” from ideas of wild and untamed to fierce, unabashed, and unafraid. Still though, while savage and ratchet may both subvert and resist, the use of savage in place of ratchet here coincides with Megan and the dancers’ notably muted twerking on this SNL stage compared to her BET performance and at other appearances and in music videos. The choreography, which included some toned-down twerking, did not contain the same emphasis on rhythmically moving flesh as other performances. Despite these features, the twerking and other butt-popping moves on the SNL stage assert that ratchetness can be a political critique. Megan and her dancers pair synchronized booty pops and hair whips in the same space as Black fists and calls for justice for Breonna Taylor, conveying a robust sensibility about how Black femmes and others can assume the right to dissent on their own terms. Megan’s acknowledgment that Breonna Taylor died because of extrajudicial state violence without much accountability highlights the disposability of Black life in these dystopic times. Moving herself through these traumas becomes “an embodied practice of controlling a marked body” that “[finds] pleasure at the site of racial and gendered injury.”70 Furthermore, ratchetness resists the human as homo economicus and protests Black death, thus serving as a regular deployment of posthuman futurity. Megan maintains ratchetness as a communicative method, betraying the notion that Black femme bodies must fall in line to be read as legible and worthy of life and dignity.

Ratchet Black Futures

The performances I discuss have engaged with the future to leverage critiques of the present, citing the everyday techniques Black people use to posit futurity. The ways these performances are tied to the present while speculating about a beyond makes André Brock’s term “post-present” an applicable description for Missy, Megan, and Cedric’s stage skits, as they are about what happens here and now and what might happen next and there.71 However, these iterations of Black futurity do not mean that every performance always holds radical and futurist characteristics. Twerking, for instance, has long been sucked into the machinations of popular culture and social media where non-Black people participate in the dance, mock it, or otherwise engage in the discourse surrounding the movement style. In the case of this discussion, it is Black performers that convey Black futurity, which is a concept always contingent on the performers’ intentionality and context.

Megan, Missy, and Cedric stake a claim to Black humanity, one that becomes powerful, defiant, and subversive especially when coupled with posthuman characteristics. These practitioners use everyday Black corporealities to challenge and combat Black people’s exclusion from the category of the human. In these cases, the posthuman cannot shed its human origins, just as Black gestures, dances, and movements cannot exist outside of a neoliberal racial capitalist context, reminding us that notions of futurity are tethered to and emerge out of the tragedies of the present. Nonetheless, it is the potency of posthuman enunciations that gives force to the also persuasive Black humanist gestures. Considering how performers use their bodies provides a deeper conceptualization of the critical significance of popular culture in Black life and the various productive spaces of commonplace Black radicality and futurity.

Notes

- Mark Dery, “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose,” South Atlantic Quarterly 94, no. 4 (1993): 182. ↩

- Kodwo Eshun, “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 2 (2003): 294, https://doi.org/10.1353/ncr.2003.0021. ↩

- Dery, “Black to the Future”; Alondra Nelson, “Introduction: Future Texts,” Social Text 71, no. 2 (2002): 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-20-2_71-1. ↩

- Ruth Mayer, “‘Africa as an Alien Future’: The Middle Passage, Afrofuturism, and Postcolonial Waterworlds,” Time and the African-American Experience 45, no. 4 (2016): 555–66; Michelle-Lee White Keith Piper, Alondra Nelson, Arnold J. Kemp, and Erika Dalya Muhammad, “Aftrotech and Outer Spaces,” Art Journal 60, no. 3 (2001): 90–91, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2001.10792080; Kodwo Eshun, “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 2 (2003): 287–302. ↩

- Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E Jones, Afrofuturism 2.0 (Lexington Books, 2015), x. ↩

- Martine Syms, “The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto,” Rhizome, December 17, 2013, https://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/dec/17/mundane-afrofuturist-manifesto. ↩

- Syms, “The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto.” ↩

- André Brock, “Black Technoculture And/as Afrofuturism,” Extrapolation 61, no. 1–2 (2020): 13. ↩

- Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction (Verso, 1998); Hershini Bhana Young, “Twenty-First-Century Post-Humans: The Rise of the See-J,” in Black Performance Theory, ed. Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita Gonzalez (Duke University Press, 2014); Tiffany Barber, “Cyborg Grammar?: Reading Wangechi Mutu’s Non-Je Ne Regrette Rien through Kindred,” in Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness, ed. Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E. Jones (Lexington Books, 2016). ↩

- Eshun, More Brilliant than the Sun, 07{113}. ↩

- Young, “Twenty-First-Century Post-Humans,” 48. ↩

- Eshun, More Brilliant than the Sun, A192. See also Mark Sinker, “Loving the Alien/in Advance of the Landing,” The Wire, February 1992; Dery, “Black to the Future”; Ytasha L. Womack, Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture (Lawrence Hill Books, 2013). ↩

- Alexander G. Weheliye, “Feenin’: Posthuman Voices in Contemporary Black Popular Music,” Social Text 20, no. 2 (2002): 39, https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-20-2_71-21. See also Marlo David, “Afrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Popular Music,” African American Review 41, no. 4 (2007): 695–707, https://doi.org/10.2307/25426985. ↩

- Weheliye, “Feenin’,” 30. ↩

- Brock, “Black Technoculture,” 18. ↩

- Justin Adams Burton, Posthuman Rap (Oxford University Press, 2017), 127. ↩

- Among other attributes, Cedric stars on the CBS sitcom The Neighborhood, and Megan Thee Stallion is an ambassador for the makeup company Revlon and is signed to Jay-Z’s Roc Nation, whose parent company is Live Nation Music. See Ivie Ani, “Megan Thee Stallion Is Officially Signed to Roc Nation ,” OkayPlayer, n.d., https://www.okayplayer.com/news/megan-thee-stallion-signs-to-roc-nation.html; “The Neighborhood (Official Site) Watch on CBS,” CBS, n.d., https://www.cbs.com/shows/the-neighborhood/; “Revlon Announces Megan Thee Stallion as Newest Global Brand Ambassador,” PR Newswire, August 6, 2020, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/revlon-announces-megan-thee-stallion-as-newest-global-brand-ambassador-301107720.html. Missy Elliott has worked with Elektra Music of Warner Music Group, and her label, The Goldmind, Inc., formerly under Elektra, is currently under Atlantic Records, also of Warner Music. See Billboard Staff, “Warner Combines Atlantic, Elektra Labels,” Billboard, March 31, 2004, https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/warner-combines-atlantic-elektra-labels-1440867/amp/; Bethany Bezdecheck, Missy Elliott (Rosen Pub, 2009). ↩

- Josh Rodgers, “Despite Earning $150K for ‘Barbershop,’ Cedric the Entertainer Admits It Bolstered His Career,” Yahoo Finance, February 23, 2023, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/despite-earning-150k-barbershop-cedric-205654188.html; In Touch Staff, “She’s a ~Savage~! Megan Thee Stallion’s Net Worth Is Major — Just like Her Rise to Music Fame,” Yahoo Entertainment, August 8, 2023, https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/she-savage-megan-thee-stallion-102056182.html; Katie Peterson, “Missy Elliott’s Net Worth: The Queen of Rap’s Massive Career,” Music In Minnesota, July 7, 2023, https://www.musicinminnesota.com/missy-elliotts-net-worth. ↩

- Missy Elliott is from Portsmouth, Virginia, Cedric the Entertainer grew up in Berkeley, MO, and Megan Thee Stallion’s mother raised her in the South Park area of Houston, Texas. These places were majority Black and working class when these performers were young (and still are). ↩

- The Original Kings of Comedy (Paramount, 2000). ↩

- Womack, Afrofuturism, 6–8. ↩

- Jonah Valez, “Katt Williams Revives Beef with Cedric the Entertainer over Allegedly Stolen Joke,” Los Angeles Times, January 4, 2024, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2024-01-04/katt-williams-cedric-the-entertainer-joke-theft. ↩

- dell22619, “Comic View Katt Williams,” YouTube, July 11, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9ty7Hes9WA. ↩

- Alana Semuels, “White Flight and Segregation,” The Atlantic, July 30,2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/07/white-flight-alive-and-well/399980/; Zawadi Rucks-Ahidiana, “Racial Composition and Trajectories of Gentrification in the United States,” Urban Studies 58, no. 13 (2020): 2721–41. ↩

- Jacob Silverman, “The Billionaire Space Race Is a Tragically Wasteful Ego Contest,” The New Republic, July 9, 2021, https://newrepublic.com/article/162928/richard-branson-jeff-bezos-space-blue-origin.

- Ayman Miazi, “Want to Go to Space? Here’s How Much SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic Cost,” Predict, September 25, 2022, https://medium.com/predict/want-to-go-to-space-heres-how-much-it-costs-4f8e6874f00b; William Harwood, “Blue Origin Resumes Passenger Flights, Carries Crew of Six and 90-Year-Old Aerospace Pioneer to Space – Spaceflight Now,” Spaceflightnow.com, 2024, https://spaceflightnow.com/2024/05/20/blue-origin-resumes-passenger-flights-carries-crew-of-six-and-90-year-old-aerospace-pioneer-to-space/. ↩

- Nettrice R Gaskins, “Deconstructing the Unisphere: Hip-Hop on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe,” in Meet Me at the Fair: A World’s Fair Reader, ed. Celia Pearce and Bobby Schweizer (ETC Press, 2014), 158. ↩

- J. Griffith Rollefson, “The ‘Robot Voodoo Power’ Thesis: Afrofuturism and Anti-Anti-Essentialism from Sun Ra to Kool Keith,” Black Music Research Journal 28, no. 1 (2008): 100. ↩

- Burton, Posthuman Rap, 30. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Weheliye, “Feenin’,” 27. ↩

- Mark Anthony Neal, Soul Babies: Black Culture and the Post-Soul Aesthetic. (Routledge, 2013), 2–3. ↩

- Neal, Soul Babies, 10. ↩

- Ibid., 120. ↩

- Simone C. Drake and Dwan K. Henderson, Are You Entertained?: Black Popular Culture in the Twenty-First Century (Duke University Press, 2020), 6. ↩

- “Sighting in the Abyss” is the name of a Drexciya song from the 1995 album, Aquatic Invasion. ↩

- Cameron Cook, “Missy Elliott Changed the Future on ‘Supa Dupa Fly,’” Vice, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en/article/43dpnj/missy-elliott-changed-the-future-on-supa-dupa-fly; Yohance Kyles, “Missy Elliott among Black Futurists Celebrated in the Little Simz-Narrated ‘Afrofuturism’ Series,” AllHipHop, April 21, 2017, https://allhiphop.com/features/samaan-ashrawi-missy-elliott-little-simz-afrofuturism-dust; R. A. Herukhuti, “Missy Elliot: Afronaut,” AfrikaIsWoke, October 1, 2022, https://www.afrikaiswoke.com/the-supa-dupa-fly-afrofuturism-of-missy-elliot/; Jasmine A Moore, “Freaks and B/Witches,” Liquid Blackness 7, no. 1 (2023): 28–43, https://doi.org/10.1215/26923874-10300456. ↩

- Moore, “Freaks and B/Witches,” 30. ↩

- Ibid., 28–29. ↩

- Emily Reily, “20 Years Ago, Missy Elliott’s ‘She’s a Bitch’ Video Redefined What Hip-Hop Could Look Like,” MTV, 2024, https://www.mtv.com/news/qenf3y/missy-elliott-shes-a-bitch-20-year-anniversary. ↩

- Moore, “Freaks and B/Witches,” 35. ↩

- Dery, “Black to the Future”; Robin James, “‘Robo-Diva R&B’: Aesthetics, Politics, and Black Female Robots in Contemporary Popular Music,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 20, no. 4 (2008): 402–23, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-1598.2008.00171.x; Tricia Rose, “A Style Nobody Can Deal With: Politics, Style and the Postindustrial City in Hip Hop,” in Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture, ed. Tricia Rose and Andrew Ross (Routledge, 2014). ↩

- Brock, “Black Technoculture,” 18. ↩

- Ibid., 23. ↩

- Elliott H. Powell, “Getting Freaky with Missy,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 33, no. 3 (2021): 149, https://doi.org/10.1525/jpms.2021.33.3.145. ↩

- Moore, “Freaks and B/Witches,” 34. ↩

- Burton, Posthuman Rap, 57. ↩

- Eshun, “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism,” 300. ↩

- This is a line from Public Enemy’s intro, “Countdown to Armageddon,” on the 1988 album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. ↩

- Megan Thee Stallion, “Megan Thee Stallion – Girls in the Hood & Savage Remix Performance {BET Awards 2020},” YouTube, July 1, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XJiirJIwXQ; Megan Thee Stallion, “Megan Thee Stallion – Savage Remix {SNL Live Performance},” YouTube, December 29, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTpilDQXYr0. ↩

- tobias van veen, “The Armageddon Effect: Afrofuturism and the Chronopolitics of Alien Nation,” in Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness, ed. Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E. Jones (Lexington Books, 2016), 65. ↩

- Zachary Wallmark, “Analyzing Vocables in Rap: A Case Study of Megan Thee Stallion,” Music Theory Online 28, no. 2 (2022), https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.28.2.10. ↩

- L. H. Stallings, “Hip Hop and the Black Ratchet Imagination,” Palimpsest: A Journal on Women, Gender, and the Black International 2, no. 2 (2013): 135–39, https://doi.org/10.1353/pal.2013.0026. ↩

- Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Beacon Press, 2002), 193. ↩

- Stallings, “Hip Hop and the Black Ratchet Imagination,” 138. ↩

- Kyra Gaunt, “YouTube, Twerking & You: Context Collapse and the Handheld Co-Presence of Black Girls and Miley Cyrus,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 27, no. 3 (2015): 249. ↩

- Jasmine Johnson, “Flesh Dance: Black Women from Behind,” in Futures of Dance Studies, ed. Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebecca Schneider (University of Wisconsin Press, 2020), 159. ↩

- Aria S. Halliday, “Twerk Sumn!: Theorizing Black Girl Epistemology in the Body,” Cultural Studies 34, no. 6 (2020): 882, https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1714688. ↩

- Gaunt, “YouTube, Twerking & You,” 248. ↩

- Bettina L. Love, “A Ratchet Lens: Black Queer Youth, Agency, Hip Hop, and the Black Ratchet Imagination,” Educational Researcher 46, no. 9 (2017): 540–41, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189×17736520. ↩

- Stallings, “Hip Hop and the Black Ratchet Imagination,” 136. ↩

- Gaunt, “YouTube, Twerking & You,” 247, 253. ↩

- Burton, Posthuman Rap, 101. ↩

- Ibid., 108. ↩

- Taylor Henderson, “Megan Thee Stallion Hints at Her Bisexuality (Again) in New Freestyle,” Pride, August 23, 2021, https://www.pride.com/celebrities/2021/8/23/megan-thee-stallion-hints-her-bisexuality-again-new-freestyle; Carmen Phillips, “Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion Are Scissoring,” Autostraddle, September 8, 2023, https://www.autostraddle.com/cardi-b-megan-thee-stallion-scissoring-bongos-music-video; CSW Digital Team, “Mariah Carey and Megan Thee Stallion Headlining LA Pride in the Park 2023,” LA Pride, March 28, 2023, https://lapride.org/mariah-carey-and-megan-thee-stallion-headline-la-pride-in-the-park-2023/. ↩

- Brock, “Black Technoculture,” 16. ↩

- Titilayo Rasaki, “From SNCC to BLM: Lessons in Radicalism, Structure, and Respectability Politics,” Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy (2016): 31–38. ↩

- Irene Oritseweyinmi Joe, “Probable Cause and Performing ‘for the People,’” Duke Law Journal Online 70 (2020): 138–60. ↩

- Nikki Lane, “Ratchet Black Lives Matter: Megan Thee Stallion, Intra‐Racial Violence, and the Elusion of Grief,” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 31, no. 2 (2021): 293–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/jola.12323. ↩

- Johnson, “Flesh Dance,” 167, 155. ↩

- Brock, “Black Technoculture.” ↩