I

The political moment in which we find ourselves is marked by danger. The rise of far-Right and straight-up Nazi movements around the world (not to mention the ascent of populist nationalists to elected positions in numerous countries, including the United States) demands a return to those modes of decisive reckoning that became unfashionable during the years when intellectuals and savvy cultural producers proudly called themselves “postmodern.” This is easier said than done, however, since it’s harder to extract oneself from a situation than it is to stumble into it. In light of this difficulty, the observations that follow oscillate between sweeping overview and tentative prescription. For even as our moment demands agenda-setting initiatives to confront the hegemonic bids of xenophobes and bigots, these initiatives must begin by working through the impasse that arises from the postmodern deterioration of our collective capacity to experience shock.

Coinciding with the advent of fascism in the 1930s, Walter Benjamin began devising a mode of materialist analysis and action that foregrounded the promise he associated with those images he called dialectical. These images were significant, Benjamin felt, for their capacity to shock viewers into recognizing their historic responsibilities and, consequently, for depositing them before the decision demanded by politics. In this way, and far from being its representational refraction, the image presaged an unmediated encounter with the world and a “leap in the open air of history.”1

Although Benjamin sometimes seemed hard pressed to provide concrete examples of such images,2 I have argued elsewhere that compelling visual approximations can be found among the popular monumental artworks that arose in response to fascist ascent during the 1930s.3 In particular, Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads (1933) and Picasso’s Guernica (1937) disclosed strong correspondences with Benjaminian themes including the relationship of fragment to whole and the decision befalling the viewer in a flash of shocking realization. To be sure, these images did not produce the cessation of happening that Benjamin had hoped for. Nevertheless, they remain useful models when considering how Benjamin’s concept might be operationalized.

Since Benjamin’s final essay on the concept of history and his subsequent suicide on the French-Spanish border, both the dialectical image and its enigmatic implications have yielded a vast secondary literature—most of which, as Benjamin biographer and friend Pierre Missac once noted, succumbed to “unsatisfying” and even “absurd” modes of commentary.4 Whatever the limitations of this literature might be, however, the fundamental question remains: what is its value—or, indeed, the value of its most prized concept, the dialectical image—today?5 What can a concept, which presumed that shock had self-evident revelatory power, contribute to the struggle against fascism at a time in which shock is no longer shocking?

I would like to make some suggestions regarding how Benjamin’s concept might be refurbished to address dynamics he could not easily have anticipated. These dynamics are primarily epistemological and are best understood in relation to what Fredric Jameson once called “the cultural logic of late capitalism.”6 Because we are now habituated to these dynamics, they strike us (if they strike us at all) as being for the most part unremarkable. Consequently, it has become difficult to evaluate the significance of the transformations they signaled, or to remain cognizant of the degree to which (for instance) they enabled Trump’s ascent.7 In order to proceed, it’s therefore useful to return to postmodernism’s primal scene to become reacquainted with its epistemological dimensions. Further, by reevaluating the visual strategies that arose in response to that scene, we can determine how they might be of use when working to refurbish the dialectical image to address the political dangers we now confront.

Despite working in different mediums and proceeding in antithetical ways, I argue that Mark Lombardi and Cindy Sherman can serve as useful reference points in this regard. I focus on these artists specifically because of their canonical status and because they are likely to be familiar even to those who did not live through the period in question or who opted to remain indifferent to the problems of visual culture. Specifically, I argue that Lombardi and Sherman’s work suggests how seduction might serve not as a substitute for shock, but as a concrete strategy for revitalizing our capacity to experience it under late-capitalist conditions.8

However, while Lombardi and Sherman provide useful clues for determining how we might move beyond our present impasse (in which the capacity for decisive action has been muted by the conceits of a postmodern epistemology that aestheticizes shock and diminishes its revelatory power), evaluating their output from the standpoint of Benjamin’s concept can’t help but reveal certain inadequacies. Nevertheless, by considering their work in tandem and imagining what it might yield in synthesis, it is possible to envision how these inadequacies might be surmounted. It’s on the basis of such a synthesis, I argue, that the program for a new political art of the kind called for by Jameson might be developed.9

And it is toward this aim (and in opposition to the ominous shadows cast by the unendurable present) that we must now proceed. To begin, I review Benjamin and Jameson’s overlapping but distinct analyses of images and shock to show how they might orient us to the challenges we confront. From this foundation, I analyze the work of Mark Lombardi and Cindy Sherman to reveal their common engagement with seduction. After cataloguing the strengths and weaknesses of these contributions, I conclude by proposing how their insights might be synthesized in the interest of revitalizing Benjamin’s dialectical image under late-capitalist conditions. Although the practice-based implications of these findings remain to be determined, the effort is justified by the likelihood that, as Benjamin once put it, they will “improve our position in the struggle against fascism.”10

II

According to Benjamin, history decayed into images.11 From this insight, he developed a theory and strategy for alerting readers to both the promise and the perils that marked their moment. Gathered together in “Convolute N” of The Arcades Project and finding their most desperate expression in his famous essay on the concept of history, Benjamin’s explorations of the dialectical image remain both enigmatic and highly suggestive when imagining how movement actors might take hold of the visual field today. For Benjamin, dialectical images arose where social relations began to crystallize around their point of greatest tension. “To thinking belongs the movement as well as the arrest of thoughts,” he proposed in one entry filed in “Convolute N.”

Where thinking comes to a standstill in a constellation saturated with tensions—there the dialectal image appears. It is the caesura in the movement of thought. Its position is naturally not an arbitrary one. It is to be found, in a word, where the tension between dialectical opposites is greatest.12

Along with the young Marx, who noted in a letter to Arnold Ruge that “the world has long dreamed of possessing something of which it has only to be conscious in order to possess it in reality,”13 Benjamin thought that—by revealing how people’s wish for happiness (and, at its threshold, for absolution) inevitably reached an impasse within capitalism’s material culture—desire’s persistence could be made to alert us to the revolutionary promise laying dormant in every situation.14 And, once it became clear that identification with the existing world corresponded more to its unrealized promise than to its manifest form, Benjamin imagined that people might embrace modes of action that, to his mind, were equivalent to “splitting the atom.”15 When coupled with the profane reckoning provoked by the dialectical image (a reckoning that enjoined the viewer to consider how—this time, and concretely—their dreams of happiness might finally be fulfilled), Benjamin envisioned that the explosive energy unleashed when desire was decoupled from the inadequacy of its posited resolution might become revolution’s driving force.

In contrast to the ambivalence of the wish image, which tended to refract its profane promise through the analytic distortions of the dream state, Benjamin held the dialectical image to be inseparable from the recognition of the revolutionary possibility inherent in the time of “the now” through which it emerged. Commenting on the distinct but interrelated character of these two image forms in her classic exegetical treatment of his work, Buck-Morss proposed that, with the dialectical image, wish images were “negated, surpassed, and at the same time dialectically redeemed.”16 Here, the dialectical image provides a means of “completing” the wish image’s dream of liberation by exposing it to the shock of recognition—by making both the promise and the means by which it might be achieved visible all at once.

By acceding to the demand the dialectical image brought in its wake, Benjamin imagined that people might come face to face with “a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past.”17 For this reason (and as early as his 1929 essay on surrealism), he proposed that revolution meant discovering “in political action a sphere reserved one hundred percent for images.”18 Only from within this sphere was it possible to address history, “the world of universal . . . actualities,” directly.19

Analyzing Benjamin’s work, Buck-Morss observed that the dialectical image was composed of two discrete but interrelated moments—one mediated and analytic, and one immediate and revelatory. Further, she proposed that, “as an immediate, quasi-mystical apprehension, the dialectical image was intuitive [and prone for this reason to produce shocking realizations]. As a philosophical ‘construction,’ it was not.” Indeed,

Benjamin’s laborious and detailed study of past texts, his careful inventory of the fragmentary parts he gleaned from them, and the planned use of these in deliberately constructed “constellations” were all sober, self-reflective procedures, which, he believed, were necessary in order to make visible a picture of truth that the fictions of conventional history writing covered over.20

The practical and pedagogical implication here is that moments of shocking realization might be produced and not merely discovered. Owing to our current impasse and to the multiplication of catastrophes that mark our age, committing to such a construction and orienting toward the “picture of truth” it yields seems more urgent than ever. Nevertheless, any effort to devise a dialectical image that neglects to consider the significant epistemological transformations that have taken place since the 1930s is bound to fail. It’s therefore necessary to transpose the epistemic premises underlying Benjamin’s conception into our contemporary, late-capitalist register. Practically speaking, this means coming to terms with the way that the unendurable present has altered our relationship to images and history—and to the experience of shock itself.

III

In his pioneering analysis of the cultural logic of late capitalism, Fredric Jameson acknowledged that, despite evident connections between the postmodern sensibilities of the 1980s and those that sometimes found expression in the high-modernist period known to Benjamin, people at the end of the twentieth century had become separated from that era by a kind of epochal break. For Jameson, this break corresponded to the dramatic transformations that multinational capitalism produced in the relationship between culture and economy during the 1960s.21 If, in the past, culture—and, in particular, visual culture—was at least formally distinguishable from the market (and if this position allowed cultural producers to formulate critical responses to dynamics arising from the economic base), the same could less easily be said by the time Jameson’s text appeared.

The problem was compounded by the fact that, in addition to culture’s economic subsumption, late capitalism prompted a transposition that led history to find expression through the register of style.22 Indeed, for Jameson, postmodernism was inseparable from its “imitation of dead styles.”23 At its threshold, this dynamic meant that the past itself was transformed, and that it came to take on the characteristics of a “stylistic connotation, conveying ‘pastness.’”24 Consequently, Jameson feared that the “retrospective dimension” required to guide “any vital reorientation of our collective future” seemed to be in danger of dissolving into a “multitudinous photographic simulacrum.”25 While Benjamin maintained that history decayed into images, Jameson alerted us to a new situation in which the two categories had become increasingly difficult to distinguish.

Written though it was at the height of our collective preoccupation with postmodern themes and implications, Jameson’s assessment is now more relevant than ever. Between the vortex of meme culture, the perils of “fake news” (both real and imagined), and the far Right’s uncanny ability to repurpose even the rainbow flag (a sign whose fixity seemed unassailable), it may even seem that we are now more postmodern than ever.26

How, then, should we orient to this scene? One might begin by striving to recapture the euphoric deconstructive chaos that marked postmodernism’s ascent—but here we must be cautious, since (as Jameson noted) the movement’s anti-systemic excesses were often encouraged by a market desperate to revitalize the waning magic of the commodity form. Acknowledging the spirit of refusal that sometimes found expression in postmodern culture, Jameson was nevertheless forced to conclude that the genre’s “own offensive features—from obscurity and sexually explicit material to psychological squalor and overt expressions of social and political defiance, which transcend anything that might have been imagined at the most extreme moments of high modernism—no longer scandalize anyone and are not only received with the greatest complacency but have themselves become institutionalized and are at one with the official or public culture of Western society.”27

Corroborating this perspective a decade later, art critic Hal Foster went so far as to suggest that the critical artist working under postmodern conditions tended to become as much a “subcontractor” to the despised system as they ever were its “antagonist.”28 Thus it was that, in a brave new world partitioned into niche markets, defiance became a hot commodity while irony and kitsch became preferred compensations for the waning use value of commodities. Rehearsing these arguments here can’t help but alert us to the degree to which, like postmodernism itself, they too have become banal. Still, and despite our habituation, both the dynamics and their consequences have grown increasingly acute. It suffices to recall Milo Yiannopoulos’ boastful proclamation that being pro-Trump was “the new punk” to realize the extent to which this is the case.

IV

Although Benjamin had anticipated the subsumption of culture to the commodity form, he only witnessed the process in its germinal—high modernist—phase.29 Now that the process is complete (or nearly complete), it’s evident that one of the central premises upon which the dialectical image relies has become less stable. If, in “Convolute N,” Benjamin stated that his goal was to uncover “the expression of the economy in its culture,”30 the challenge today is reading the “expression” of one sphere in another when the distinction between them has become—at best—purely formal.

Responding to this unprecedented indistinction, Jameson concluded that ideas derived from “Benjamin’s account” were now “both singularly relevant and singularly antiquated.”31 In order to address the challenges associated with this new terrain (challenges which have only grown more acute since Postmodernism first appeared), Jameson sought to devise a “cognitive map” suitable to a world whose coordinates had become distorted by late capitalism’s contractions of space-time. Homologous in some respects to Benjamin’s dialectical image, the cognitive map Jameson sought to devise was meant to yield “a situational representation [of] that vaster and properly unrepresentable totality which is . . . society’s structures as a whole.”32

Confronted with the task of representing the “properly unrepresentable” totality, Jameson noted that the cultural products of the postmodern era—though often assembled through pastiche, and frequently devolving into apologias for global exploitation—could also be read as “particular new forms of realism.”33 From this vantage, the critical task involved determining how to map “a new and original historical situation in which we are condemned to seek History by way of our own pop images and simulacra of that history, which itself remains forever out of reach.”34 Although the cultural logic of late capitalism made it seem impossible to access the signified directly, Jameson wagered that its dimensions—its spatial and temporal coordinates, its mass and density—might still be read off of its signifying trace.

In practical terms, the collapse of the distinction between culture and economy enjoins us to elaborate epistemic habits and visual strategies that do not rely—as all previous avant-gardes have done—on the critical distance afforded by their prior separation. Since, as Jameson noted, it’s impossible to “return to aesthetic practices elaborated on the basis of historical situations and dilemmas which are no longer ours,” we must find ways of updating (completing) our high-modernist strategies by tempering them in the crucible of cultural indistinction.35

In Postmodernism, Jameson never got much further than calling for such a project. Instead of concrete propositions, he provided a series of useful but vague guidelines: “the new political art (if it is possible at all) will have to hold to the truth of postmodernism, that is to say, to its fundamental object—the world space of multinational capital.” But while he remained short on specifics, Jameson had no doubts regarding the project’s urgency. Indeed, since—in his view—an art of this kind would allow us to “grasp our positioning . . . and regain a capacity to act and struggle” in a context hitherto marked by “confusion,” the stakes were very high.36 The same remains true (has become more pressing still) today.

How, then, might the dialectical image be transformed to address the cultural logic of late capitalism? How can Benjamin’s concept—which emphasized shock as though it had self-evident revelatory power—be reconfigured to work at a moment in which shock is no longer shocking? I propose that the dialectical image might be salvaged by supplementing its shock with an aesthetic-epistemological seduction capable of reconnecting viewers to the now-lost referent. In order to reveal how such a seduction might practically be achieved, it is now time to consider the work of Mark Lombardi and Cindy Sherman. Despite their obvious differences, these two artists played a central role in devising strategies and motifs for addressing the postmodern condition. Moreover, in struggling with its epistemic demands, they produced images that echoed aspects of Benjamin’s conception while simultaneously enlisting seduction to address the historical lacunae we now confront. By returning to postmodernism’s primal scene, I propose that we might find a point from which to trace a line of flight beyond our current impasse.

V

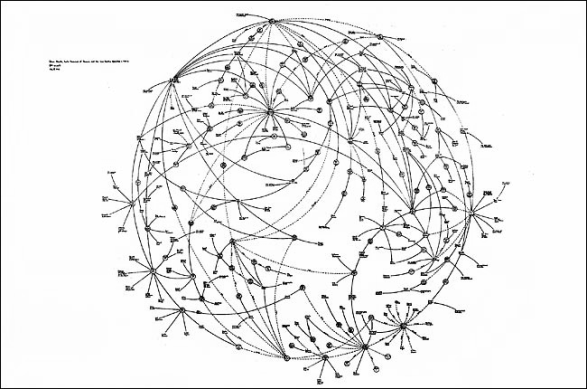

Like Benjamin, neo-conceptual artist Mark Lombardi was preoccupied with collecting and organizing information in the interest of illuminating revelation. Between 1994 and his death by suicide in 2000, he also developed a novel representational strategy that suggested an intriguing visual approximation of Jameson’s cognitive map. After a career that saw him shuffle between stints as a reference librarian, a curator, and a researcher, Lombardi began producing works in which data collection and the analysis of social relations congealed into “narrative structures.”37 Taking financial scandals, business deals, and shady connections between corporate and political interests as his starting point, he devised “delicate filigree drawings that map . . . the flow of global capital.”38

In an artist statement from 1997, Lombardi described how he assembled these narrative structures by using “a network of lines and notations . . . meant to convey a story, typically about a recent event . . . like the collapse of a large international bank, trading company, or investment house.”39 Motivated by the desire to “explore the interaction of political, social and economic forces in contemporary affairs,” his approach was strongly reminiscent of Benjamin’s efforts to “assemble large-scale constructions out of the smallest and most precisely cut components.”40 “Working from syndicated news items and other published accounts,” said Lombardi, “I begin each drawing by compiling large amounts of information about a specific bank, financial group or set of individuals.”

After a careful review of the literature I then condense the essential points into an assortment of notations and other brief statements of fact, out of which an image begins to emerge. My purpose throughout is to interpret the material by juxtaposing and assembling the notations into a unified, coherent whole. . . . Hierarchical relationships, the flow of money and other key details are then indicated by a system of radiating arrows, broken lines and so forth. . . . Every statement of fact and connection depicted in the work is true and based on information culled entirely from the public record.41

Like Benjamin, Lombardi strove to make the scattered fragments of daily life intelligible. After his death, his holdings were found to include “14,500 index cards with information on the subjects of his investigations, all drawn from publicly available sources.”42 This compulsive collecting neatly echoed Benjamin’s own habits while struggling to illuminate the nineteenth century through the Paris arcades. And so, while there are many intriguing biographical connections between Lombardi and Benjamin (connections that culminate in their respective deaths by suicide), it’s clear that their methodological connection is still greater.

To give but one example: in his unpublished manuscript addressing the history of panoramic painting (a subject to which Benjamin devoted a section of his “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century”), Lombardi remarked upon how, in struggling to give an account of the world, “the historian is reduced to random glimmerings obtained via shards, scraps and bits of ephemera to begin the reconstruction.”43 Although he did not cite Benjamin directly in this context, the sentiment clearly echoes Benjamin’s contention that, methodologically speaking, the arcades project’s goal was to make the “rags, the refuse” of everyday life “come into their own . . . by making use of them.”44

Given this confluence, it’s not surprising that Lombardi curator Robert Hobbs tended to describe the artist’s work in Benjaminian terms. According to art critic Eleanor Heartney, Hobbs was “immediately impressed” with the “sheer beauty” of Lombardi’s work, which used “the delicacy of the curving lines” to delineate the “abstract force fields created by the global movement of money.” By Heartney’s account, Hobbs designated these works “variously as webs, rhizomes,” and (notably) “constellations.” But alongside such revealing designations (and this is decisive for understanding the work’s importance for our purposes), Hobbs also declared that Lombardi’s creations were nothing short of a “mental and visual seduction.”45

Like Hobbs, cultural journalist Ryan Bigge was also taken by the conjunction of analytic clarity and seduction in Lombardi’s work. Indeed, as far as Bigge was concerned, the artist’s mastery of the curved line recalled nothing so much as the “simple yet seductive contours of latitude and longitude” even as they revealed the “vicious circles” of global capitalism itself.46 Pitched somewhere between art appreciation and art criticism, comments like these should not be mistaken for an analysis of epistemic premises. Nevertheless, in their very formulation, one begins to detect the means by which seduction might return us to the shock of recognition.

VI

For Bigge, Lombardi’s genius owed to his ability to “make [the] abstract movements of capital concrete and comprehensible.”47 Nevertheless, the constructive principle upon which these narrative structures were based ensured that the image’s comprehensibility was never instantaneous. Instead, it was achieved by oscillating between critical distance and engaged proximity. Seduced by the promise of discovering the work’s meaning, the viewer is literally compelled to sway back and forth. As Bigge recounts it, “the density” of Lombardi’s images required the viewer to “take a number of steps backward, since the facts can easily overwhelm the piece’s beauty.” Indeed, it was “only from a distance” that the work could be “seen, rather than read.”48 Still, density is seductive in its particularity; the viewer, now retreated to a point from which the whole is perceptible, is overtaken by the urge to dive back in.

Because its particular content remains indeterminate when contemplated from a distance that would allow the viewer to consider the beauty of the whole, Lombardi encouraged a process of analytic engagement that moved the viewer (now seduced) to fixate once again upon its constellated components. Like falling from heaven and breaking the cloud cover, the viewer is drawn through the aesthetic realm to confront the shocking implications of the depicted scene; however, even here, neither the beauty nor the conceptual coherence of the totality are eclipsed (since the viewer, overwhelmed, is compelled to step back and begin the process anew). By prompting this alternation in vantage points, Lombardi achieved through formal means an effect comparable to the one that stereoscopy achieves for vision and dialectics achieves for epistemology.

Along with their success in holding true to what Jameson called “the world space of multinational capital,” Lombardi’s images also coincide with Benjamin’s premises for the dialectical image, where historical fragments are brought together in illuminating constellations. However, whereas Benjamin produced stereoscopy through the montage of the historical citations themselves,49 Lombardi achieves this same effect through modulations in the epistemic position of the viewer—and it is through this process that seduction is activated.

Which is not to say that montage plays no role in Lombardi’s oeuvre, though his works certainly do not amount to montage in the conventional sense. Drawn in pencil and on one surface, they stand in sharp contrast to those early twentieth-century works assembled from multiple sources and aimed at yielding generative discord. Nevertheless, when considered from an epistemological and not a purely formal perspective, it’s clear that Lombardi did bring discrete fragments into combination in illuminating ways. Constellating lines trace social relationships between fragmented and discontinuous nodes and, in the process, forge a new socio-spatial proximity (a new cognitive map) giving form to the “world space of multinational capital.” If, in the past, montage enabled artists to illuminate the trans-local and trans-temporal dimensions of the social through the assemblage of discontinuous objects, Lombardi revitalized this strategy by conceptually distilling these objects to their most primitive formal notation.

As a result, and in contrast to the kind of shock yielded by montage during the early twentieth century,50 Lombardi’s seduction revealed how the epistemic promise that Benjamin attributed to shock might be revitalized by subverting its contemporary aestheticization. By showing how capitalism’s trans-local organization becomes possible through concrete and localized points of relay, his work even suggests how we might begin to take history itself to be the object of a collective, redemptive labor process. For these reasons, and as an approximation of the new “political art” called for by Jameson, Lombardi’s work should be considered an important reference point for anyone hoping to produce dialectical images today. Still, when measured against the demands that Benjamin associated with his concept, it becomes clear that this work ultimately falls short.

To understand why, it’s necessary to consider how Lombardi’s narrative structures depict a world of objectified relations in which the viewer herself is never directly implicated. Because the composition’s constellated references do not pass through the viewer, they organize no implicated point from which to engage. As a result, even as Lombardi’s images provoke forms of analytic reckoning that are consistent with the dialectical image, they are not likely to yield the forms of decisive action that Benjamin also sought.

According to Hobbs, “Lombardi wanted . . . to pry people loose from habitual ways of thinking, so that they would look anew at their world and find far-ranging connections where none were thought to exist.”51 And this undoubtedly happens; however, while Lombardi’s viewer can look on with amazement or gnawing disgust as the trans-local relations of capitalist exploitation take on a concrete form, the images themselves organize no space for engagement. Since the narrative recounted by Lombardi’s structures is already whole (since, unlike in Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads, there is in fact no contradiction to resolve), efforts to “complete” the scene through decisive action become superfluous.

At best, Lombardi’s representational strategy fosters outrage at capitalist impunity. At worst, it becomes a machine yielding smug satisfaction. For while his formal-conceptual objectifications make the world visible in its trans-local, constellated totality, the price of that objectification is that—like a weather pattern—the world itself begins to seem like a pre-social, reified form that might be contemplated from some untenable Archimedean point (and though the seduction might bring you close, you will never become implicated in the constellation itself). Standing outside the depicted scene, the viewer is implicitly exonerated. And since the viewer is extrinsic to the drama, the drama itself is doomed to remain a distorted representation of the social. For this reason (and along with Brecht, who made the same observation in a different but parallel context), we must insist: “the present-day world can only be described to present-day people if it’s described as capable of transformation.”52

VII

How might the political-epistemological lacunae at the heart of Lombardi’s work be addressed? In order to answer this question, it is useful to revisit the work of Cindy Sherman, an artist whose images are in some sense a perfect antithesis to Lombardi’s neo-conceptualist experiments. Working in photographic self-portrait, Sherman gained notoriety for her uncanny ability to reveal the precise means by which narrative fictions come to organize perception. In so doing, she also illuminated important aspects of the social that would remain overlooked by Lombardi’s global networks. Because Sherman was among those artists who—starting in the 1970s—began actively exploring embodiment and site-specificity, this corrective function should be understood as deliberate.

Indeed, as art historian Hannah Westley recounts, the “move to reground art” during the period in which Sherman’s work first appeared was considered “urgent” by artists confronting “the serial objects of minimalism, simulacral images of Pop and demonstrations of conceptual work” that had presaged Lombardi’s own constructions two decades later.53 In contrast to Lombardi’s precursors, Sherman used her work to highlight how the postmodern subject came to be marked by what seemed like an irreconcilable conflict between representation as an all-consuming social-indexical system and those nebulous aspects of Being that refused encapsulation. It therefore followed that her work embraced the “return to the body and the social, to the abject and the site-specific” that marked the art of that era.54

In her Untitled Film Stills, shot between 1977 and 1980, Sherman produced self-portraits that—through changes in composition, costume, lighting, and tone—effectively demonstrated that “subjectivity” was primarily a representational accomplishment. By mining the archive of established film genres and personae while maintaining a consistent presence at the center of each image, she revealed the degree to which the cultural logic of late capitalism had subordinated the ontological question of Being to the more malleable register of style. Based on this premise, Sherman’s works should seem whimsical; however, viewers and critics alike have agreed that their actual effect has been far more unsettling. Why is this so?

When considered as a series so that both the range of Sherman’s deliberate filmic citations and her constant presence at the center of each image become explicit, the Untitled Film Stills begin to appear dialectical. By mobilizing representational norms unmoored by concrete referents while—at the same time—maintaining a consistent presence in each image, Sherman intensified the tension between simulacrum and self-portrait by actualizing both simultaneously (it is a montage, but one of superimposition). In these images, two discrete ontological premises coexist but are never resolved. Occupying each image in a way that suggested a “more” (a beneath or beyond that exceeds representational capture), Sherman effectively staged a conflict between representation and Being.

According to art critic Peter Schjeldahl, by taking “the movie fiction of a character observed in vulnerable solitude as the departure point for an exploration, in depth, of vulnerability itself,” Sherman seduced viewers into confronting the “shock of deep recognition”—an experience that, for Schjeldahl, was “not altogether agreeable.” On this basis, he located “the drama” in Sherman’s work “in the abyss between matter and mind, object and subject.”55 Initially imperceptible, this point—this “abyss”—is gradually revealed through the staged antagonism of antithetical ontological premises. Initially, representation subsumes (seems even to constitute) Being. But if this is true, then what is this unsettling thing, this remainder that escapes symbolization?

On first blush, the Untitled Film Stills accord with the feminist desire to interrogate the representational norms that organize and maintain feminine status. By citing works of low-culture and transposing them into the realm of fine art (as Duchamp and Warhol had done before her), Sherman exposed them to forms of scrutiny they may previously have escaped. But despite these formal, stylistic, and genre-specific citations, Sherman remained the clear subject-object of her work. By downplaying her status as creator while remaining a consistent (though consistently malleable) presence throughout, she discovered a means of turning the viewer’s encounter into one of “quasi-mystical apprehension.”56 Indeed, like Benjamin before her, Sherman confirmed that effective social criticism “needn’t say anything. Merely show.”57

But while the Untitled Film Stills were exceptionally compelling as a critique of representational norms, they did not yet constitute an explicit critique of representation as such. If, as art critic Norman Bryson once put it, postmodernism was characterized by the “absorption of reality within representation,” the challenge confronting those unwilling to remain trapped in the prison house of signs first involved uncovering the means by which representation had come to seem like an “apparently enclosed order” with “no fire escape.”58 Only then does a jailbreak become conceivable. The Untitled Film Stillspointed to this challenge; however, they did not resolve it.

VIII

It’s therefore not surprising that Sherman’s subsequent work became explicitly concerned with the point at which representation fails. In her centerfold images of the 1980s, this search led her (still the subject-object of her work) to depict women posed in accordance with the genre conventions of the pornographic pinup. Like the Untitled Film Stills before them, these works made representational norms their object of scrutiny. At the same time, however, Sherman gestured toward the unrepresentable by mobilizing a look of distracted focus, which suggested either an enormous inside or an enormous outside that stubbornly refused encapsulation within the image frame. What Sherman “sees” remains inaccessible to the viewer, who is forced to confront not only her own scopophilic prying but also the implications of that realm (in her, in me, in the work, in the world) that escapes symbolization.

By the mid-1980s, and as a logical extension of her previous experiments (and as a forerunner to the Whitney’s famous showcase of 1993), Sherman began exploring death and that zone of abjection marked by indistinction.59 This work closely echoed themes elaborated by Julia Kristeva in Powers of Horror. For Kristeva, the significance of abjection could be attributed to the fact that it “draws me toward that space were meaning collapses.”60 Moreover, like the seductions of Lombardi’s stereoscopy, Kristeva found that “the time of abjection is double” since it’s marked by a “veiled infinity” (an abyss, in Schjeldahl’s terms) even as it heralds “the moment when revelation bursts forth.”61 Once again, the viewer succumbs to seduction’s sway.

Derived from and associated with Lacan’s account of the Real (that thing which escapes symbolization and thus produces unsettling effects), Kristeva’s abjection also shares an important conceptual homology with Benjamin’s dialectical image. Indeed, Benjamin was endlessly preoccupied with the moment when revelation “bursts forth” (it is the moment of “quasi-mystical apprehension,” of shock, to which Buck-Morss alerted us). As in Kristeva, this moment obtains when the “veiled infinity” of empty, homogenous time (the time of mythological histories told from the standpoint of “progress”) is sundered.62 Consequently, for Benjamin, “the dialectical image is an image that emerges suddenly, in a flash” and that, through revelation and the decision it demands, makes the past citable in all its moments.63

It therefore followed that, for Benjamin, the desire for redemption was stimulated by recollections of an existence prior to the fall.64 Similarly, Kristeva proposed that the experience of abjection arises when the subject discovers “that all its objects are based merely on the inaugural loss that laid the foundations for its own being.”65 This is politically significant, since the unsettling experience of lack also forces us to consider the precise profane dimensions of the missing piece. At its logical conclusion, the experience of lack opens onto political decision, and to the possibility of committing to an act that might surmount the inaugural loss, which—through abjection—can now be perceived directly.

Rendered though they are in the language of theoretical abstraction, such connections allow us to begin appreciating the properly Benjaminian dimensions of Sherman’s work. While Benjamin highlighted the political significance of the corpse in the German “mourning plays” of the seventeenth century, Sherman’s images from the mid-‘80s revealed how the corpse could likewise be used to illuminate dynamics particular to late capitalism.66 Indeed, her work from this period managed to see the corpse, not only from the outside, but also (as Benjamin had suggested with respect to Baudelaire) “from within.”67

But while these Benjaminian associations suggest that, through her work, Sherman managed to combine scopophilic seduction with bludgeoning shock in pursuit of profane illumination, her images, like Lombardi’s, remain ambivalent. This is because the viewer contemplating Sherman’s abjection is confronted with the shock of recognition (of the remainder that draws us back to the scene of indistinction—but now we return with consciousness intact) only after passing through the seductions of abjection, the seductions of the car crash we can’t (can’t help but) look at through our fingers. Indeed, under postmodern conditions, the abject is encountered first and foremost as an aesthetic conceit, which would be fine, or even advantageous, if it weren’t for the fact that Sherman’s seduction is itself ambivalent.

On the one hand, it seems to prepare the viewer for a shock from which it’s impossible to distance one’s self. Here, as in Lombardi, seduction reveals itself to be an important factor in the elaboration of a contemporary dialectical image—though, through her engagement with the Real, Sherman surpasses Lombardi by implicating the viewer in the depicted scene. On the other hand, however, this same seduction has shown signs of being susceptible to an easy aestheticization, which renders the experience wholly commensurate with the cultural logic of late capitalism. Such aestheticization is incompatible with the dialectical image and its demands.68

To get a sense of how far we’ve fallen, it suffices to recall how for curator Magrit Brehm—and in keeping with postmodernism’s fetishistic embrace of depthlessness and its allergy to what (following Jameson) we might think of as hermeneutic modes of social-intellectual engagement—the subject of Sherman’s “Disgust” series was “not the moldy food but the designed surface” itself.69 Indeed, in Brehm’s account, disgust operates first and foremost as “an artistic experience.”70 Though always in danger of being undone by the Real, Brehm’s comments reveal the extent to which postmodern epistemology is capable, through aestheticization, of representationally subsuming even abjection. And as irreducible Being is reduced to the stylistic conceits of the image surface, the ontological stereoscopy that gave Sherman’s work its depth and dialectical force becomes flat; as a result, the image becomes decoupled from the historical anchor that would allow us to conceive it metonymically.

Perhaps it was inevitable. After all, even Kristeva noted that—with the publication of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (a Benjamin favorite)—abjection began to seem “fashionable.”71 Channeled into the symbolic just as capitalism began to rob experience of all gravity (and here we might recall Jameson’s contention that postmodernism heralded the “waning of affect”72), abjection has paradoxically become a means of re-infusing depthless and undifferentiated lives with something resembling significance. At a moment when many commodities have been deprived of all but the representation of their past use values, the Real has become a hot commodity. And the more the encounter with the Real came to mark the last reliable verification of Being (and here we need only to recall those pornographic genres promising real tears, or those successful businesses specializing in slum tourism), the more likely it became that abject art would degenerate into a provocation whose ultimate effect is the reaffirmation of the status quo.73

IX

Through their innovative uses of montage and the modulations in perspective they provoked, Lombardi and Sherman devised visual strategies that coincided with many of the analytic premises outlined by Benjamin in his consideration of the dialectical image. And while the representational strategies they deployed were in some senses antithetical, both artists used modes of visual seduction to reactivate shock’s epistemological force while subverting its contemporary aestheticization. At the same time, their distinct (but similarly incomplete) conceptions of the social meant that neither Lombardi nor Sherman produced images that rose to the level of Benjamin’s concept (a problem which, to be fair, Benjamin struggled to address as well). Still, we must ask: if Lombardi’s narrative structures fell short by over-objectifying the social and imagining that it could be envisioned from some untenable Archimedean point, and if Sherman’s self-portraits missed the mark by relinquishing abjection before connecting the corpse to the world from which it arose and to which it is related as a kind of metonymic encapsulation, is it possible that—through the synthesis of these artists’ greatest insights—these shortcomings might be surmounted? Given the stakes of our present and the conditions under which we now operate, it is an experiment worth considering.

To prepare the ground for such a synthesis, it’s useful to begin by recalling that, despite their differences, both Lombardi and Sherman made use of seduction to reactivate shock. Following their lead, we can therefore imagine that, today, the dialectical image must refuse to become visible all at once. If, as Buck-Morss proposed, such images were comprised of two discrete modes of engagement (with one related to its concrete and mediated production and the other to its quasi-mystical apprehension), the contemporary context demands that the process of production become an aspect of what is finally recognizable. Today, the dialectical image must be processual and marked by duration. Seduction initiates the process; the payoff is the shock. It is the shock of recognition, but it must still and forever be wrested from the dangerous likelihood of its aesthetic subsumption.

But while seduction can reactivate shock, it’s clear that, in and of itself, seduction is not enough. The lacunae in Lombardi and Sherman’s work enjoin us to find means of overcoming the limits of their respective visualizations of the social. This might be achieved either through the constellation of their respective strategies or by devising new representational approaches that combine their epistemic premises in some greater unity (saturated with tension though yet it may be).

X

In Postmodernism, Jameson never got further than outlining a series of general guidelines for the development of a new political art capable of addressing the epistemological challenges posed by late capitalism. Through our return to postmodernism’s primal scene and our consideration of canonical works by Mark Lombardi and Cindy Sherman (works that are not normally considered together in the fields of art history or art criticism), we have pushed this project forward by pointing out the important role that seduction—and, in turn, process and duration—can play in helping to revitalize the dialectical image to address the challenges we now confront. As the wreckage accumulates around us and habituates us to the echoes of our own outrage, recovering our capacity for shock will become increasingly important. It is my hope that these observations have provided some useful guidelines for achieving this aim.

Notes

- Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 261. ↩

- By speaking primarily about the dialectical image’s potential effects, Benjamin did little to clarify the means by which such an image might consciously be produced; still less did he provide an extensive catalogue from which one might infer its provenance, character, or composition. The problem becomes explicit when we consider how, in the “Theses,” Benjamin suggested that the French Revolution’s identification with the Roman Republic allowed Robespierre to lay hold of “a past charged with the time of the now which he blasted out of the continuum of history.” On first blush (and despite the narcotizing effect of its poiesis), such an account seems plausible. But claiming that this resonant myth was a dialectical image required that Benjamin overlook the fact that Robespierre’s Roman burlesque operated primarily as a compensation for the bourgeois revolution’s inadequacies. As is well known, this was Marx’s take on the matter. Despite the inevitable lack of heroism in bourgeois society, he recounted, “it nevertheless took heroism, sacrifice, terror, civil war . . . to bring it into being.” Consequently, the revolution’s architects and gladiators ransacked “the classically austere traditions of the Roman republic” to gather “the ideals and the art forms, the self-deceptions that they needed in order to conceal from themselves the bourgeois limitations of . . . their struggles.” Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Selected Works, vol. 1. (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1973), 399 ↩

- AK Thompson, “Matter’s Most Modern Configurations: Rivera, Picasso, and Benjamin’s Dialectical Image,” in Premonitions: Selected Essays on the Culture of Revolt (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2018), 133. ↩

- According to Missac, already by 1984, “a general critical bibliography” comprised of secondary sources on Benjamin contained “no less than 180 pages, despite lacunae that are certainly excusable.” Given the general character of this secondary literature, Missac invited his reader to consider “why studies of Benjamin are often unsatisfying and even ‘absurd’ and then look at how one can avoid the dangers that even a cursory analysis of such studies reveals.” It is in part to this task that the current project is dedicated. Pierre Missac, Walter Benjamin’s Passages (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995), 15. ↩

- Given the enormity of the literature, it is beyond the scope of this investigation to review it in any systematic way. As a result, I have limited myself to drawing upon the work of Susan Buck-Morss who, in my estimation, remains the most valuable secondary source on Benjamin’s oeuvre. This is especially true with respect to her exegetical treatments. Beyond this, I have followed Missac’s lead by returning to Benjamin’s texts to see what they might reveal when considered under our new, imperiled circumstances. ↩

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991). ↩

- The past few years have witnessed heated debates online and in the popular and alternative press about postmodernism’s role in helping to secure Trump’s victory. See, for example, Michiko Kakutani, “The Death of Truth: How We Gave Up on Facts and Ended Up With Trump,’ The Guardian, July 14, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jul/14/the-death-of-truth-how-we-gave-up-on-facts-and-ended-up-with-trump, and Aaron Hanlon, “Postmodernism Didn’t Cause Trump. It Explains Him,” The Washington Post, August 31, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/postmodernism-didnt-cause-trump-it-explains-him/2018/08/30/0939f7c4-9b12-11e8-843b-36e177f3081c_story.html. ↩

- As a concept, seduction played an important role in postmodernism’s theoretical development. Indeed, Jean Baudrillard’s Seductionbecame an important reference point in the elaboration of postmodern critiques of logocentrism, which facilitated the capacity to countenance indeterminacy and celebrate play. While my use of the concept is in some respects adjacent to Baudrillard’s, it should go without saying that I do not succumb to the latter’s presupposition that action at the level of the signifier is the only game in town. Instead, seduction is invoked here as an invitation to embark upon modes of investigation that maintain the presupposition of a tangible reality or meaning beneath or behind the image, the sign. Jean Baudrillard, Seduction (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991). ↩

- According to Jameson, “the new political art (if it is possible at all) will have to hold to the truth of postmodernism, that is to say, to its fundamental object—the world space of multinational capital.” By his account, meeting this representational challenge would allow us to “begin to grasp our positioning as individual and collective subjects and regain a capacity to act and struggle which is at present neutralized by our spatial as well as social confusion.” Jameson, Postmodernism, 54. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 257. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 476. ↩

- Benjamin, Arcades, 475. ↩

- Quoted in Benjamin, Arcades, 467. ↩

- Indeed, as Benjamin put it, “every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter.” Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 264. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 463. ↩

- Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project(Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991), 146. ↩

- Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” 263. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,” in Reflections (New York: Schocken Books, 1978), 191. ↩

- Benjamin. “Surrealism,” 191. ↩

- Buck-Morss,The Dialectics of Seeing, 220. ↩

- Jameson,Postmodernism, 5 ↩

- It is significant to note that—in The Arcades Project—Benjamin actively distinguished the study of images, which he took to be the substance of historical knowledge, from the study of style. Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 462. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 18. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 19. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 18. ↩

- Appropriations of the rainbow flag by the “alt-right” began to be noticed in 2016, with the Nation reporting on how “street artist Sabo and his Unsavory Agents claimed responsibility for a spate of guerilla posters . . . featuring the Gadsden flag’s rattlesnake (Tea Party), laid over a rainbow flag (LGBTQ), with the hashtag “#shootback” (anti-gun control).” Since then, the rainbow flag has been incorporated into an extensive array of rightwing memes, which interpret its discrete bands of color as a metaphor for national distinctness and purity. Ian Allen, “‘Alt-Right’ Is Not a Thing. It’s White Supremacy,” The Nation, November 23, 2016, https://www.thenation.com/article/alt-right-is-not-a-thing-its-white-supremacy/. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 4. ↩

- Hal Foster, The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 60. ↩

- Considering newspapers that included feuilletons on their front page alongside the news of the day, Buck-Morss highlights Benjamin’s engagement with the fact that, in the nineteenth century, “the line” between “political fact and literary fiction” became incredibly thin. But while he anticipated how the “oppositions in which we have been accustomed to think may lose their relevance” and sought to develop an appropriate corresponding pedagogical strategy, even Benjamin would have been hard pressed to divine the extent of culture’s current economic subsumption. Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing, 140. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 45. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 51. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 49. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 51. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 25. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 50. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 54. ↩

- Eleanor Heartney, “The Sinister Beauty of Global Conspiracies,” in Defending Complexity: Art, Politics, and the New World Order (Lennox, MA: Hard Press Editions, 2006), 85. ↩

- Heartney, “The Sinister Beauty,” 83. ↩

- Mark Lombardi, “Artist Statement,” 1997, www.pierogi2000.com/flatfile/mlavailable3.html. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 461. ↩

- Lombardi, “Artist Statement.” ↩

- Heartney, “Sinister Beauty,” 85. ↩

- Ryan Bigge, “Making the Invisible Visible: The Neo-Conceptual Tentacles of Mark Lombardi,” Left History 10, no. 2 (Fall 2005): 133. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 460. ↩

- Robert Hobbs, Mark Lombardi: Global Networks(New York: Independent Curators International, 2006), 84. ↩

- Bigge, “Making,” 128. ↩

- Bigge, “Making,” 128. ↩

- Bigge, “Making,” 128–129. ↩

- The organization of material in “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” for instance, sees Benjamin pairing historical figures with elements of material culture. Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Reflections (New York: Schocken Books, 1978). ↩

- Skeptical of its potential, Georg Lukács nevertheless conceded that montage was “capable of striking effects, and on occasion can even become a powerful political weapon. Such effects arise from its technique of juxtaposing heterogeneous, unrelated pieces of reality torn from their context.” Finally, he thought, “a good photomontage has the same sort of effect as a good joke.” Georg Lukács, “Realism in the Balance,” in Aesthetics and Politics, by Adorno et al. (London: Verso, 2002), 43. ↩

- Hobbs, Mark Lombardi, 41. ↩

- Bertolt Brecht, “Can the Present-Day World be Reproduced by Means of Theatre?” in Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic(New York: Hill and Wang, 1992) 274. ↩

- Hannah Westley, The Body as Medium and Metaphor (New York: Rodopi, 2008), 179. ↩

- Westley, The Body, 179. ↩

- Peter Schjeldahl, Cindy Sherman: Centerfolds (New York: Skanstedt Fine Art, 2003), 35. ↩

- Sherman has deliberately refused to even inscribe her works with particular titles, which is the artist’s due. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 460. ↩

- Norman Bryson, “House of Wax,” in Cindy Sherman: 1975-1993(New York: Rizzoli International Publishers, 1993), 222. ↩

- The Whitney Museum, Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art: Selections from the Permanent Collection (New York: The Whitney Museum, 1993). ↩

- Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 2. ↩

- Kristeva, Powers, 9. ↩

- Throughout “Convolute N,” Benjamin makes several attempts to distinguish his conception of history from the one pervasive among bourgeois historians seduced by the myth of progress. In one such entry, Benjamin states, “the concept of progress had to run counter to the critical theory of history from the moment it ceased to be applied as a criterion to specific historical developments and instead was required to measure the span between a legendary inception and a legendary end of history. In other words: as soon as it becomes the signature of historical process as a whole, the concept of progress bespeaks an uncritical hypostatization rather than a critical interrogation.” Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 478. ↩

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 473. ↩

- Benjamin, “Paris,” 148. ↩

- Kristeva, Powers, 5. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama (London: Verso, 2009). ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Central Park,” in The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 163. ↩

- Indeed, such aestheticization cannot help but strike us as a faint echo of the fascist aestheticization of politics against which Benjamin warned in his essay on the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. ↩

- Magrit Brehm, Ahead of the 21st Century: The Pisces Collection (Hatie Cantz, 2002), 9. ↩

- Brehm, Ahead, 8. ↩

- Kristeva, Powers, 20. ↩

- Jameson, Postmodernism, 10. ↩

- Similarly, Hal Foster has noted that while pop art may have sought to “use mass culture to test high art,” the overwhelming effect was instead to “recoup the low for the high, the categories of which remain mostly intact.” Foster, The Return of the Real, 60. ↩