The Japanese Relocation, a short propaganda film created by the US Office of War Information in 1942, ends with a long, panning shot of the Manzanar relocation camp. The camera slowly pans to the left, unfurling seemingly endless rows of barracks in the middle ground and the peaks and valleys of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the background (Figure 1).1

Providing voice over to the scene, Milton Eisenhower, the director of the US War Relocation Authority (WRA) at the time and the brother of Dwight Eisenhower, asserts that US incarceration of people of Japanese descent sets world standards in the treatment of “people who may have loyalty to an enemy nation.”2 In so doing, he claims the US balances the concerns of national security with the “principles of Christian decency” that can be the model for all.3 Eisenhower’s phrasing is revealing in its tortured attempt to avoid the most salient social and legal problems of incarceration for the US public at the time. Note how stating “people who may have loyalty to an enemy nation” avoids direct acknowledgment of the racial dimensions of incarceration since the suspicion of disloyalty, sabotage, and espionage disregard citizenship status.4 Note also how invoking “principles of Christian decency” elides the problem of the constitutionality of Japanese incarcerations, which did not become legally justified until the notorious Korematsu v. United States case in 1944.5

Yet these inconsistencies and tensions are quickly elided by the film’s central claim about the so-called Japanese relocation: the camps are “pioneer Communities.”6 The closing shot only reaffirms such an argument. The sublimity of the mountains and desert plains attests to a raw natural world that tests the mettle of would-be pioneers. Or, as Eisenhower explains, the “land is raw, untamed but full of opportunity.”7 Such a formulation repeats the central narrative trope of US frontier mythology—the unbounded land signals an unlimited horizon of progress.8 Indeed, Eisenhower leans into this progressive frontier narrative when he describes the film’s account of Japanese incarceration as a “prologue to a story that is yet to be told.”9 Of course, this rehearsal of American frontier mythology is not the same as its nineteenth-century predecessor. For one, the pioneers adventurously staking their fortune in the raw lands of the frontier are not the white mountaineers of the nineteenth century. Second, the closing of the continental frontier has opened onto an oceanic horizon in the twentieth century. Last, the ends of the frontier are not material progress and civilizational expansion but political and social inclusion. If one is not to take the pioneering framing to be simply government propaganda, then how is one to understand this revision of frontier mythology, particularly its racial imaginary? How does it mediate the complex US imperial and domestic racial politics of the emerging American century?

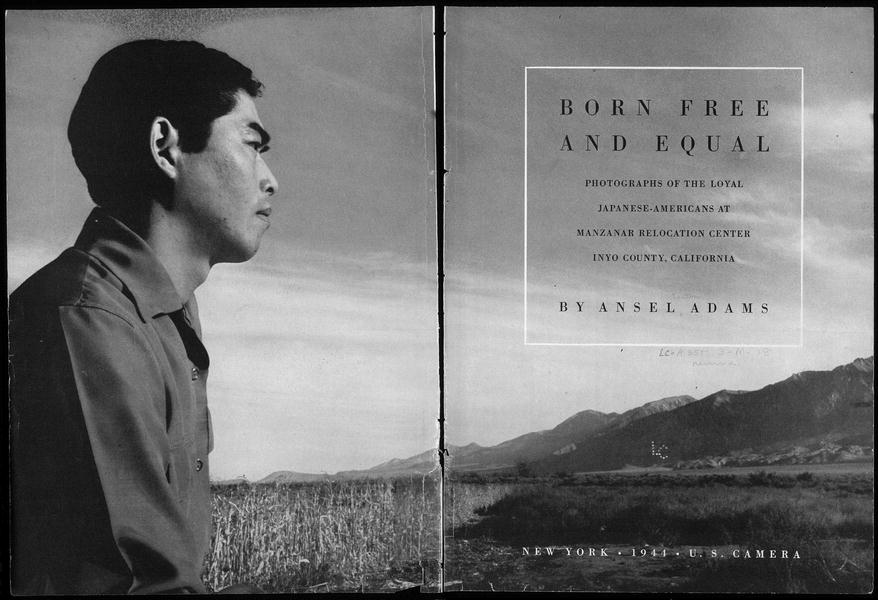

This article answers these questions by examining the role of landscape in the visual and narrative representation of Japanese incarceration in Ansel Adams’s Born Free and Equal (Born Free).10 Specifically, by analyzing the way it both draws upon and reworks what art historian Albert Boime calls the magisterial and reverential gaze,11 I argue that Born Free revises the thematic and visual trope of US frontier mythology to articulate a US racial liberal “structure of feeling” in the American century.12 Born Free oscillates between landscapes and portraits to establish an aestheticized account of frontier nature. In so doing, it forges a vision of racial democracy that can simultaneously “Americanize” the Japanese body and universalize US global Power.13 In other words, like the much lauded all-Japanese American 442nd Infantry Regiment, the 100th Infantry Battalion, the all-African American 332nd Fighter Group, and the 477th Bombardment Group, Born Free’s aestheticized frontier positions the minoritized Japanese body as a national icon that testifies to the racial liberal values of the US, and thus can authorize American (neocolonial) power globally.14

Japanese Incarceration and Imperial Landscape

Within popular US historical memory, the history of Japanese incarceration—if remembered at all—is seen as an exceptional domestic event of wartime panic that has no relation to US histories of US colonialism. Yet, the history of Japanese incarceration was deeply tied to the inter-imperial dynamics between the US, Japan, and Great Britain across the Pacific. Indeed, the bombing of Pearl Harbor, which led to the infamous Executive Order 9066, was an attack that was neither exclusively in Hawaii nor only in the US Pacific colonies. It was part of Japan’s inter-imperial strategy across the Pacific Rim, which included both US colonies and British colonies like Hong Kong, Malaya, and Singapore.15 Thus, it is unsurprising that the incarceration of people of Japanese descent was not exclusively a US phenomenon; Canada and Australia pursued similar policies. Though not acknowledged by the national public, the US imperial investments in the Pacific was certainly on the minds of political and military leaders at the time. Indeed, as historian Daniel Immerwahr notes, FDR’s infamy speech had initially included the Philippines alongside Hawaii as places of paramount national concern after the attack but was later relegated to the longer list of other territories attacked by Japan.16 In so doing, Hawaii was discursively incorporated into US national boundaries while the Philippines was tossed among other foreign colonial places. Such revisions reflect connections between US imperial life abroad and domestic (racial) order at home, particularly the domestic political calculations deemed necessary to galvanize national publics towards war.

Furthermore, the colonial underpinnings of Japanese incarceration were not only the result of the United States’ supposedly anomalous imperial adventures abroad after the 1890s; critically, they were continuous with longer US histories of settler colonial expansion. Hence, as Native studies and Asian American studies scholars have recently shown, the practices of Japanese incarceration drew upon and intersected with the carceral practices and geographies of longstanding US settler colonialism.17 Nothing exemplifies this better than how the location of so-called relocation centers and isolation centers were placed on Native lands such as the Poston Relocation Center, Gila River Relocation Center, and the Leupp Isolation Center. Predictably, there was administrative and personnel overlap and crossover between the War Relocation Administration (WRA) and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). For instance, John Collier, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, advocated for the Poston Relocation Center, which was run by his office. Moreover, Dillon S. Myer, the Director of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) for the much of its existence, later became the Commissioner of Indian Affairs during which time he led the Indian termination policy.

Historical amnesia of the colonial underpinnings of Japanese incarceration is not simply the effect of their tertiary position within popular historical narratives of WWII but an effect of the logics and ideology of US colonialism itself—both earlier settler expansion and overseas imperial ambitions. According to historian Alyosha Goldstein, US colonial practices of the eighteenth and nineteenth century were characterized by an “incorporative” logic.18 US dominion over acquired territory was rationalized as building an “empire of and for liberty” through the assumption of eventual statehood of land and the extension of citizenship to subject populations.19 After the 1890s, US colonial practices were governed by an “unincorporative” logic.20 US dominion of overseas territories was understood to be temporary in the service of training subject populations in the democratic ways of self-government à la the “white man’s burden.”21 As different as these logics seem to be, Goldstein importantly observes that “the doctrines of territorial incorporation and unincorporation each professed to affirm the benevolent intent of US dominion while justifying particular strategies for territorial acquisition and control.”22

Japanese incarceration was precisely drawn into the “unincorporative” logic of US colonialism to the extent that their treatment is supposed to emblematize the beneficence of the US to the rest of the world. This is perhaps best seen in the way that practices of incarceration changed after 1943. As historian Takashi Fujitani shows, the state and military rationales and the logistical aims of incarceration shift from a racially exclusionary practice to a racial liberal assimilative project. Such a quick about face on the matter does not demonstrate the US state’s progressive moral development. Rather, Fujitani convincingly shows that the practice of incarceration indexes the simultaneous and competing rationalizations and strategies of the US state’s total war regime as it both dealt with the internal pressures of managing resources and mobilizing populations as well as encountered competing imperial projects in the Pacific and emergent postcolonial geopolitical actors. Hence, during the initial exclusionary operations of incarceration, a central military fear was that people of Japanese descent would foment resentment and revolution in US racialized minority communities, particularly African American communities, in direct alliance with the Japanese imperial state. This was due to Japan’s propaganda campaign that positioned themselves as the “champions of the darker races” of the world, which connected the status of US racialized minorities with racialized colonial subjects across the world.23 Yet, people of Japanese descent were not exclusively coded as a transnational threat to the domestic racial order. Later, they were elevated as “loyal Japanese Americans” and became a potent ideological symbol of the US as a multiracial democracy to counter Japanese propaganda and to court emerging postcolonial nations under the aegis of Pax Americana in the post-war global order.

Such patriotic representations of Japanese Americans and benevolent representations of incarceration were crafted through a carefully managed process by the US state. As historian Jasmine Alinder explains, the military prohibited incarcerated people of Japanese descent from photographing the assembly centers and relocation camps.24 (However, some were able to sneak in cameras). At the same time, through the WRA’s photography section, the US state hired photographers to document the whole process but censored images that were seen to undermine the US.25 Furthermore, the Office of War Information created propaganda films about incarceration and distributed them widely through the War Activities Committee of the Motion Picture Industry. Later, however, these restrictions were relaxed and the camps allowed visitors, such as Ansel Adams, to bring cameras and provided photography studios for the incarcerated people. These, of course, were still heavily managed by the state, particularly restricting photography of the barbed wire fences and guard towers of the camps.

Yet, censorship was not the only means of regulating the representation of Japanese incarceration towards US colonial interests, more mundanely and perhaps more insidiously, was the way that these representations (such as The Japanese Relocation that I began with and, as I will show, Adams’s Born Free) drew upon longstanding visual conventions of landscape art and cultural codes of frontier mythology to rationalize these policies. In other words, they are part a tradition of what visual cultural theorist W. J. T. Mitchell calls “imperial landscapes.”26 By this concept, Mitchell challenges common understandings of landscape as a genre of painting in art history to, instead, broaden and re-contextualize landscape as a “multisensory medium” in the repertoire of colonial representational practices.27 Importantly, Mitchell notes that the representational scope of imperial landscape does not just extend to the foreign colonized lands: “it is [also] typically accompanied by a renewed interest in the re-presentation of the home landscape, the ‘nature’ of the imperial center.”28 In other words, imperial landscaped rationalized colonial projects by representing not only foreign lands as in need of civilization but also domestic lands as a site of imperial identification. Asian American studies scholar Iyko Day extends Mitchell’s theorization by elaborating the racial logics of imperial landscapes.29 More specifically, she convincingly shows how romanticized visions of Western landscapes in the 1920s and 1930s (like Ansel Adams’s oeuvre) were indicative of romantic anticapitalist logics of settler colonialism. They were not only a nostalgic response to the rise and development of capitalism, but also functioned as sites of white settler colonial identification that simultaneously naturalized settler claims to land and erased Native existence and dispossession.

Yet, the imperial landscape of Japanese incarceration does not simply accept whole cloth the visual conventions of earlier US imperial landscapes. They are modified in ways that index the unincorporative logics of twentieth-century US colonial practices. In particular, they draw upon and revise what art historian Albert Boime calls the “magisterial gaze” and the “reverential gaze.”30 Characterized by a downward high-angle visual perspective, the magisterial gaze was a visual trope that united multiple schools of nineteenth-century US landscape painting and indexed a “sociopolitical ideology of expansionist thought” that undercut the natural world.31 In contrast, the reverential gaze was visual trope of European landscape painting characterized by an upward low-angle visual perspective and indexed sociopolitical ideology of nationalist thought. As I will show, the imperial landscape of Japanese incarceration draws upon both visual tropes as way to address the ideological and racial demands of the emergent geopolitical vision of an integrated Pacific that will come to dominate the American century after the war.

Americanizing the Japanese Body and Universalizing US Global Power

In the fall of 1943, after prompting from his longtime friend Ralph Palmer Merritt from the Sierra Club, Ansel Adams went to Manzanar, California, and photographed the lives of incarcerated people of Japanese descent.32 Located between the Sierra Nevadas and Death Valley, Manzanar proved to be an ideal location for Adams as he was all too familiar with the area. What emerged out of this project was a short booklet that documented camp life and Adams’s own reflections on Japanese incarceration.

What is striking about Born Free is the way Adams used the opportunity to combine his own interest in nature photography with documentary photography. The prominence of both has led scholars to find a frontier subtext in Born Free.33 For instance, Asian American visual culture studies scholar Elena Tajima Creef writes, “In the logic of Adams’s narrative, the Japanese Americans are fortunate to have been transported to the desert where they can be transmuted by the landscape and disciplined through the camp’s self-sustaining work into productive citizens.”34 Like the wilderness of the nineteenth-century frontier, the “desert wasteland” is subjected to human control through Japanese labor and thus brings civilization where putatively there was none.35 In the process, however, the Japanese American is made anew. The struggle with the brutal conditions of nature strips the Japanese American qua frontier pioneer of their cultural past—or perhaps, in this case, racial past—and transforms them into, to quote from Turner himself, “a new product that is [Japanese] American.”36

Such a reading of Born Free’s frontier subtext is certainly accurate. However, I would suggest that it does not fully capture the ideological role of frontier imagery since it pivots on the notion of the dignifying and transformative effect of work. Indeed, even though Adams himself implicitly draws upon it throughout Born Free,37 he forwards a very different relationship between the Japanese body and frontier nature as the booklet’s central aim, which he describes in the Forward:

For many years I have photographed the Sierra Nevada, striving to reveal by the clear statement of the lens those qualities of the natural scene which claim the emotional and spiritual response of the people. In these years of strain and sorrow, the grandeur, beauty, and quietness of the mountains are more important to us than ever before. I have tried to record the influence of the tremendous landscape of Inyo on the life and spirit of thousands of people living by force of circumstance in the Relocation Center of Manzanar.38

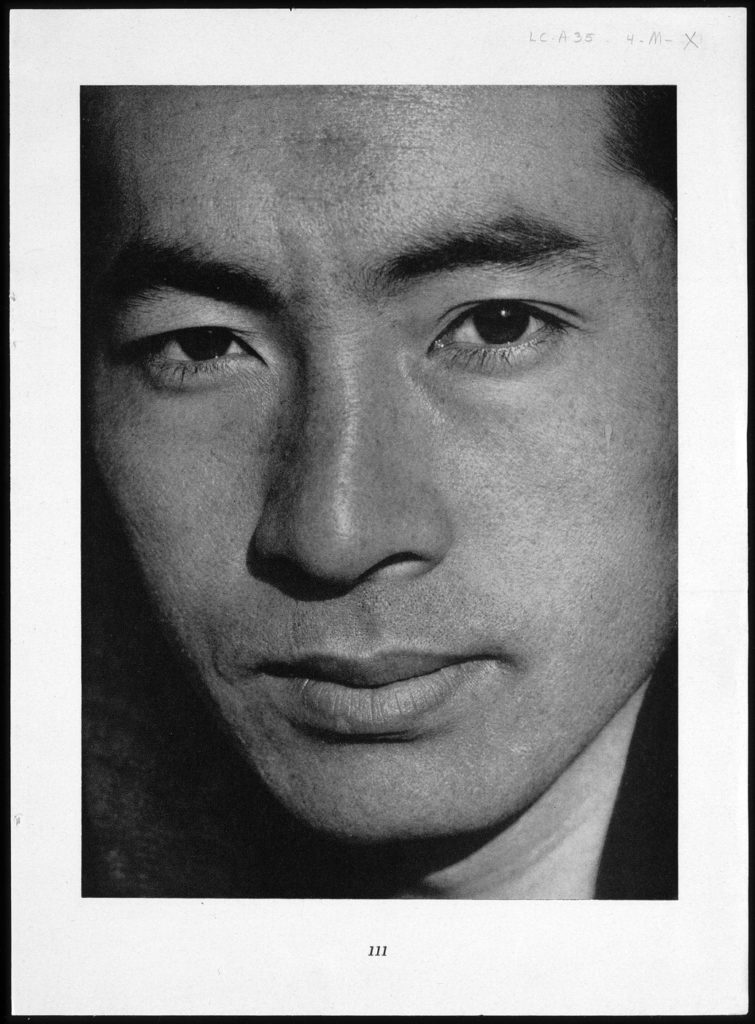

In highlighting the “natural scene[’s . . . ] claim [on] the emotional and spiritual response on the people,” Adams is thus interested in capturing the aesthetic experience of frontier nature for the incarcerated people of Japanese descent.39 Born Free’s opening image visualizes precisely this aesthetic relationship (Figure 2).40 The two-page photograph contains a profile of a Japanese American man staring contemplatively on one side, and the burgeoning crescent of a mountain range on the other. Situated in the foreground of the frame, the Japanese American man dominates the image, endowing him with a stately quality. His majesty is further fortified by the camera’s slight upward angle that places the viewer in a reverential position. In effect, Adams has visually elevated the Japanese American man, if not greater than, at the very least, equal to the splendor of the mountains. Yet, this monumentalizing does not show the Japanese American man working away on the soil, struggling against nature; rather, he is sitting and staring off toward the distant mountains. Indeed, like looking up at a mountain, the upward angle of the photograph directs the viewer to look at its peak, the man’s face as he looks out into the distance. In other words, rather than the dignifying and transformative effect of work and the commanding power of human labor on the natural world, the photograph illustrates an act of aesthetic contemplation and reverence through the experience of the natural sublime.

This aesthetic encounter, I suggest, encapsulates Born Free’s organizing visual grammar—specifically the link between its portraits and its landscapes—as a scene of the aesthetic experience of frontier nature. In this way, my reading of Born Free builds on Thy Phu’s analysis of landscape ideology in detention photography of Japanese incarceration.41 However, I would like to historically specify her claim by situating the aesthetic appeals to frontier nature in Born Free as part of the racial liberal project to transform notions of American identity as racially inclusive. Adams’s aestheticism towards natural landscapes is unsurprising. As Jasmine Alinder points out, Adams had long self-identified as an aesthetician and sincerely believed in the social significance of aesthetic experience of nature.42 But what is the social and political significance of aesthetic experience in the context of Japanese incarceration in WWII? As I will show, this aestheticizing of frontier nature and the Japanese body as well as linking them together through an aesthetic vision not only offers an account of the Americanization of the Japanese American that parallels and reinforces the one that pivots on the dignifying effects of work. More significantly, the aestheticism offers an imaginative position beyond history that can performatively redefines American identity and belonging as inclusive of racial difference. Put differently, Born Free’s visualization of aesthetic experience gives visual form to racial liberal structure of feeling since its appeal to an experience of transcendence identifies the Japanese body with romantic frontier landscape to erase their “alienness” and thus indigenize them as one among many other settlers in a racial liberal US.43

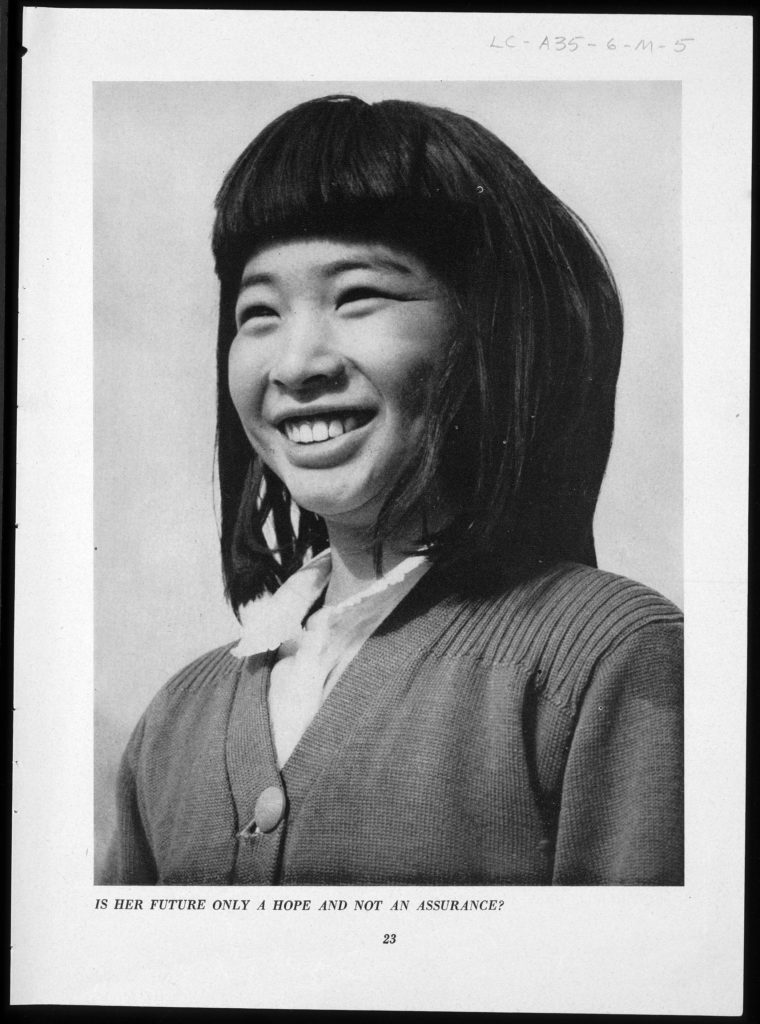

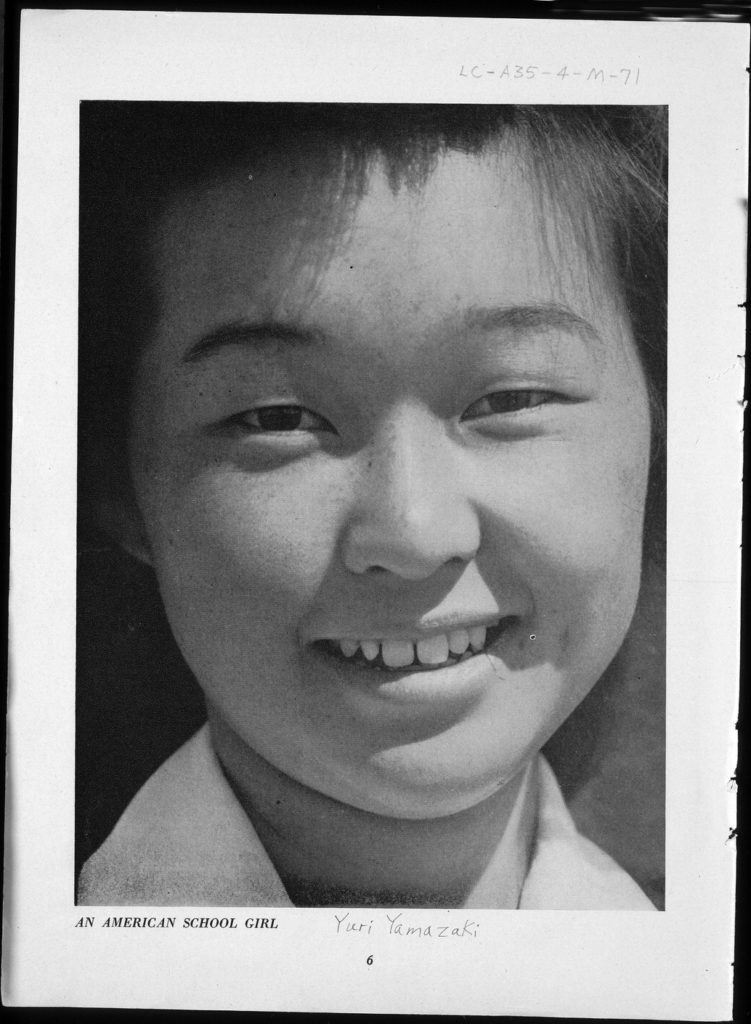

Born Free’s portraits are striking in their strong close-ups of the face. Such direct attention explicitly counters the numerous racist caricatures of people of Japanese descent that were circulating throughout the US visual public sphere at the time.44 Indeed, as Creef observes, Born Free’s first couple of portraits largely feature school-age Japanese American girls (Figures 3, 4, 5).45 Through their dress and hairstyles, the portraits encode them within the US visual idiom of innocent white girlhood and thus attenuate the threat of racialized Japanese masculinity. However, Adams’s gender choices do more than familiarize people of Japanese descent as non-threatening. Adams’s composition had a more specific aesthetic project in mind—one that fed into the normalization of Japanese Americans to the US public. Adams explains this project in his “note on photography”:

I have felt strongly that most sociological photography is unnecessarily barren of human or imaginative qualities; a professional idiom has developed which in its stark realism often defeats its purpose. In this undertaking I felt that the individual was of greater importance than the group; in a sense each individual represents the group in a most revealing way. I also feel that a consistently oblique approach to people weakens the impact of their personalities. Hence most of the heads are photographed looking directly into the lens and therefore directly at the spectator.46

Here, Adams raises a stylistic and philosophical objection to what he calls “sociological photography.”47 Stylistically, sociological photography decenters individual personality and thus, philosophically, obscures the “human or imaginative qualities” of people.48 Even though Adams criticizes this “stark realism,” it is does not mean Adams is not also working within his own “professional idiom” in Born Free.49 Indeed, as Thy Phu notes, Adams self-consciously photographed his Japanese American subjects as if they were sculpted natural objects akin to the mountains themselves to elicit a merger between portrait and landscape.50 This landscape style hinges most notably on both Adams’s zone system technique, which “produc[es] the desired range of negative densities at the moment of exposure,” and his modernist compositional eye towards simplified geometric forms.51 This style of photography is best illustrated in Adams’s iconic images of cloud banked skies, moonlit deserts, or enormous geologic formations. Such renderings, however, are less about the natural world per se than the role that it plays in human life. In particular, these natural objects form a visual idiom to capture epiphanic aesthetic experiences of the sublime.52 In this regard, the individual that Adams describes is a specific romantic conception in which aesthetic experience unifies man with the natural world.

Such an aesthetic ideology works at two levels at the same time in Born Free. It makes the Japanese American body more mountain-like while also making the mountains more human-like. As quasi-mountains, the portraits are meant to be gazed upon with reverence as the viewer is subtly placed below the eye akin to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European landscape paintings. Furthermore, Adams’s portraits carefully attend to the tonal gradations and contrasts to highlight sculpted facial features such as the dimple dips and the line curvatures of the cheeks, the subtle shadows that follow the jawline, and the dramatic tonal and textural contrast of the hairline (Figures 3, 4, 5). Such photographic detailing communicates more than the smiling facial gestures of the subject to instead elevate the Japanese American face as a noble national icon. Yet, like the opening photography, the aestheticizing of the face does not only liken it as a natural aesthetic object, but also, the face becomes a viewing subject in its own right. Hence, the low-angled shots of the portraits also direct the viewer’s gaze upward toward the implied line of sight of the subject. As Adams explains in his “note on the photography,” such head shots are intended to stage a direct encounter between the viewers and the photographed subject. Yet, as these initial portraits of young Japanese American girls make clear, the portraits’ implied line of sight also signifies aesthetic vision. Indeed, the subjects are positioned in either three-quarters or two-thirds views (Figures 3, 4, 5), and thus, the portraits have the young girls looking out into the distance.

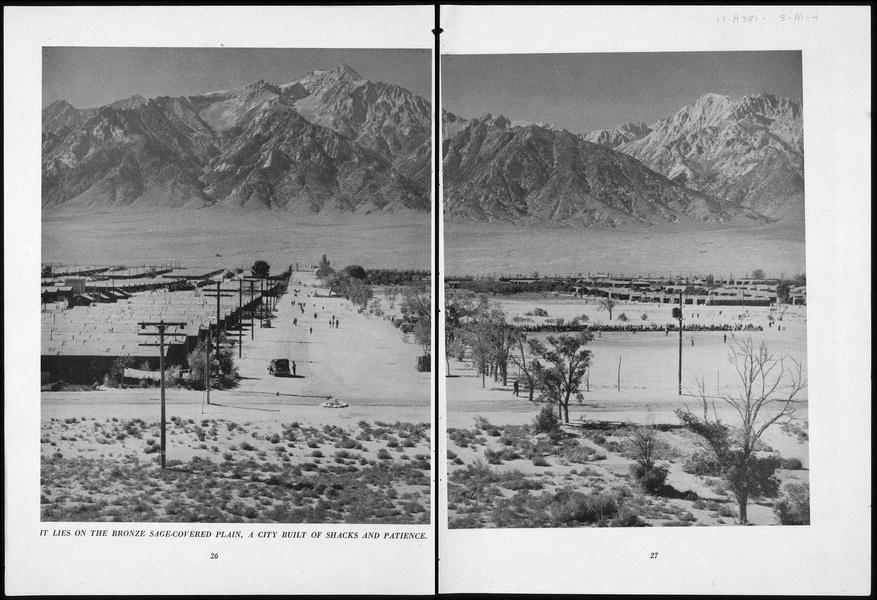

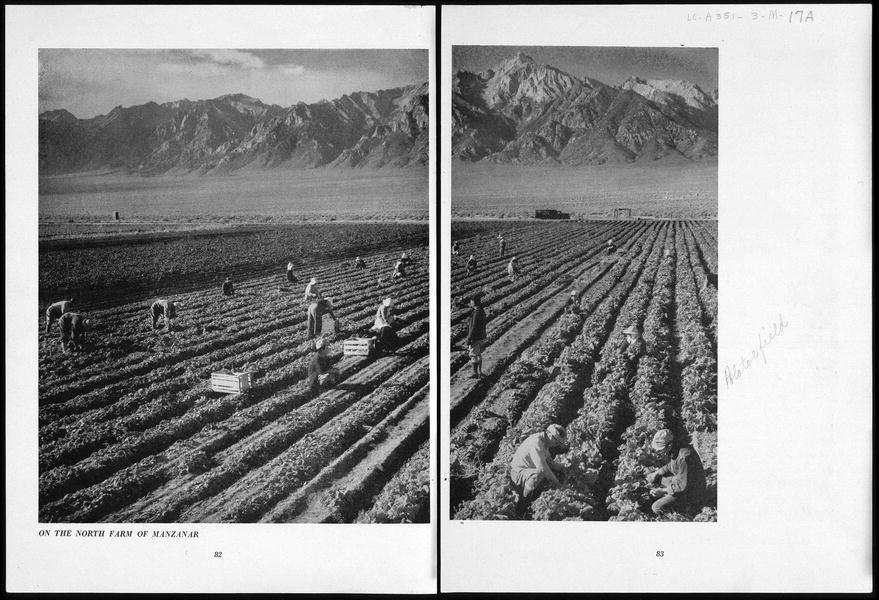

But at what are they looking? It is, of course, frontier nature. Hence, Born Free’s landscape photographs continue this visual motif of aesthetic gazing—reverential and magisterial alike. Like earlier projects, Adams inserts several photographs of the Sierra Nevadas in Born Free that draw upon his characteristic zone system to represent the natural sublime. These large two-page photos visualize a romantic drama of nature through the contrasts and subtle shifts in the tonal gradations of light in the image. On the one hand, Adams draws upon the familiar semiotics of the American frontier. He writes, “The huge vistas and the stern realities of sun and wind and space symbolize the immensity and opportunity of America—perhaps a vital reassurance following the experiences of enforced exodus.”53 Indeed, the photographs rehearse the civilizational expansion of earlier landscape imagery—from the expansive housing to the agricultural productivity. Such imagery thus concretizes Eisenhower’s description of the camps as pioneer communities by framing them within the visual tropes and conventions of the frontier.

Yet, the privileged vista of Adams’s eye is not the rolling wilderness but the majesty of the mountains.54 A case in point are the two photographs that prominently feature both the mountains and the camps (Figures 6 and 7).55 Asian American visual culture studies scholar Thy Phu reads these photos as Adams’s claim that “the camp functioned . . . in harmony with nature.”56 Yet, I would suggest that this harmony has less to do with a pastoral vision of humanity’s organic connection to the natural world than with the sublimity of humanity’s tiny scale compared to the enormity of the mountain. That is, rather than positing a physical connection between the human world of the camp and the natural world of the mountains, the photographs underscore a kind of distance between them. In Figure 6, the horizontal spread of the barracks marks the outer boundaries of the camp, which outlines the natural boundaries of the desert horizon. Indeed, the central road that runs perpendicular to the barracks leads to the photograph’s vanishing point that sits under the mountains. Figure 7 similarly plays with horizontal and vertical lines. The neat diagonal columns of row crops spread horizontally across the lower and middle registers of the picture plane. Yet, they do not extend upward; they are notably cut off by the road and the dessert horizon. In this way, both photographs emphasize the insurmountable physical distance of the mountains from the human world of the camps.

Additionally, the photographs stress the difference in scale between the natural world of the mountains and the human world of the camps. This is most evident in Figure 6 as the human figures are mere dots with hardly any recognizable human form. In this way, the photographs suggest that the mountains come not only to dwarf human actors and built environments, but they also are removed from the reach of human activity altogether. Yet, the reverse cannot be said. If the human world cannot touch the mountain, the sheer size of the mountains overcomes the distance from the human world. The mountains themselves thus lord over the camps from on high with their line of sight, watching imperiously the tiny actions of humans below.

Though the mountains may be beyond the reach of human labor, they are not beyond the reach of aesthetic contemplation. Hence, the mountains or rather the mountains’ positionality take center stage, more so than the camps themselves. Indeed, the vertical and diagonal lines of the photographs (e.g. the road in Figure 6 and the crop rows in Figure 7) do not simply direct the viewer’s gaze toward the mountains; they specifically direct it to their highest peak. Thus, like Born Free’s portraits, the mountains are not only a natural aesthetic object to behold, but they are also an aesthetic positionality from which to imagine. As an aesthetic positionality, the mountains offer a temporal frame to understand the national significance of the camps. This notion is best captured when Adams states

When all the occupants of Manzanar have resumed their places in the stream of American life, these flimsy buildings will vanish, the greens and flowers brought in to make life more understandable will wither, the old orchards will grow older, remnants of paths, foundations and terracing will gradually blend in the stable texture of the desert. The stone shells of the gateways and the shaft of the cemetery monument will assume the dignity of desert ruins; the wind will move over the land and the snow fall upon it; the hot summer sun will nourish the gray sage and shimmer in the gullies. Yet we know that the human challenge of Manzanar will rise insistently over all of America—and America cannot deny its tremendous implications.57

Here, Adams implicitly analogizes Japanese American re-entry into the “stream of American life” with the disappearance of the built environment and the resurgence of natural wildlife, in that both are supposed to be the return to the natural order of things.58 Yet, given Adams’s final line, it would be inaccurate to claim that the Manzanar simply fades away to be forgotten. Its “human challenge” holds “tremendous implications” for the US.59 Clearly, the challenge is the democratic contradiction of the political and social inequality of race. Thus, the passage points to two distinct temporal framings of Manzanar. The first suggests that Manzanar is fundamentally anomalous to the natural course of things. Or, in Adams’s words, Manzanar is just a “detour on the road” to “citizenship” for the Japanese American.60 The second implies the opposite social and temporal condition; Manzanar is representative of, and thus marks a turning point in, the course of things. The United States’ response to the challenge of Manzanar will serve as the template to respond to the endemic problem of race in the nation. Or, as Adams states, “The treatment of the Japanese American will be a symbol of our treatment of all minorities.”61 These contradictory socio-temporal interpretations can be reconciled only by offering a transcendent position that stands outside of them. Enter the mountains. For Adams, their sublimity does not only come from their physical size, but also from their very durability. Indeed, throughout Born Free, Adams contrasts the permanence of the mountains with the transience of the camps. From their transcendent geo-historical viewpoint, the contradictory temporal views of Manzanar are resolved as an episode in the spasmodic movement of national progress. As Adams writes, “At Manzanar, in the presence of the ancient mountains, another tragic episode of history struggles for solution.”62

When taken together, Born Free’s portraits and landscapes form two halves of the same scene of aesthetic contemplation. The Japanese body faces not just the viewer directly but also reverentially upward to the mountain. In turn, the mountains are imputed their own line of sight, magisterially peering to the Japanese American onlooker. They thus posit a transcendent position beyond the human scene of the camps, for which the Japanese body simultaneously looks upon and embodies itself through its visual identity with the mountains. Furthermore, the viewer is also invited to identify with the incarcerated Japanese Americans through their shared activity of looking. That is, the incarcerated Japanese Americans look at the mountain; the viewer looks at the photographs. Yet, more than this, the appeal is reinforced further since strewn intermittently throughout Born Free are two-page spreads of mountains set in the backdrop of an expansive sky. Thus, the viewer is tied to incarcerated Japanese Americans not simply by the act of looking but by the act of looking at the sublimity of frontier nature. Taken together, the visual grammar of Born Free (i.e. the way the photographs collectively direct a recognition of the mutual experience of the natural sublime between incarcerated Japanese Americans) enables the cultural and political recognition of not only a new national personage—the Japanese American—but the Unites States’ national character as racially democratic.

Conclusion

Born Free ends with a portrait that is perhaps the clearest expression of this mid-century US racial liberal structure of feeling (Figure 9).63 Unlike nearly all other portraits, the last is an extreme close-up of the face. The hairline and neck are practically cropped out. Importantly, it is shot at eye level. Thus, the viewer is no longer reverentially positioned below; instead, the viewer is made to directly face the subject, Hirata. His facial expression, moreover, is ambiguous. Unlike prior portraits, he is not inviting the viewer with a smile. He is also not disabusing the viewer with anger. Instead, the portrait frames Hirata to be intensely staring at the viewers, piercing them with his eyes.

Symbolically, then, the final portrait operates quite differently from the rest. All the photographs, portraits, and landscapes alike sought to normalize the Japanese American for the viewer. On the one hand, they straightforwardly enfolded the Japanese body into recognizable visual categories of Americanness. On the other hand, as I have argued, their visual grammar sought to transform those visual categories into a liberal democratic vision through appeals to the sublimity of frontier nature. The final portrait, on the other hand, does not prompt recognition; it demands more from the viewer. Though not expressed in anger, Hirata’s gaze is a call for responsibility—not as an indictment for culpability but as an imperative to respond with political action.

In this regard, then, the final portrait is less a break from the prior photographs than their culmination. Indeed, as historian Jasmine Alinder notes, Adams was purposeful in the ordering of the images, especially with this closing portrait of Yuichi Hirata.64 Part of this ordering is the way that work becomes an organizing rubric since many of the portraits are grouped together by profession. But another one has been a developmental structure. As noted before, the initial portraits are of young girls, and, as the booklet proceeds, the portraits shift to mainly adult men. Such development linkage is reinforced further since the first portrait of Yuri Yamazaki has the same formal composition as the final one (Figure 8).65 In so doing, the portrait of Harata marks the narrative entry of the Japanese American as a moral-political agent in Born Free, one who is not simply recognized but who can now act morally and politically to press rights claims. Ideologically, however, the stakes of the portrait’s moral and political demand is not so much the well-being of Japanese Americans or the historical injustice of their wartime incarceration, but the future of the US as a racially liberal democratic society that can take moral leadership in the unfolding postcolonial order of the American Century.

Notes

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation (Washington: War Activities Committee of the Motion Picture Industry, 1942), Film. ↩

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation. As historian Roger Daniels points out, incarceration is a better term than internment to describe what happened to West Coast Japanese Americans in 1942 since the vast majority were US citizens. Roger Daniels, “Words Do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans,” in Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century, ed. Louis Fiset and Gail Nomura (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2005), 190–214. Also, for clarification, when discussing the historical people who were incarcerated, I will refer to them as “people of Japanese descent” due to their varied citizenship status and historically complicated self-identification. When discussing their visual representation, I will refer to them as “Japanese Americans” ↩

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation. ↩

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation. ↩

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation. ↩

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation. ↩

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation. ↩

- As historian Greg Grandin observes, the term “frontier” diverged from the term “border” by the end of the nineteenth century. Rather than a fixed geographical line, frontier “suggest{ed} a cultural zone or a civilizational struggle, a way of life” (116). In such a context, Frederick Jackson Turner’s great contribution was “to embrace the unsettledness of the concept” by elaborating and multiplying the meanings of the frontier while, at same time, channeling them into a simple explanation of American development (116). Turner’s account was so compelling that it achieved common sense in not only elite circles, but also in the US public sphere at large. For more, see Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2019), 116.. ↩

- US Office of War Information-Bureau of Motion Pictures, Japanese Relocation. ↩

- Ansel Adams, Born Free and Equal: Photographs of Loyal Japanese-Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center, Inyo County, California (New York, NY: US Camera, 1944). ↩

- The reverential and magisterial gaze refers to opposing visual tropes and compositional orders that have shaped the landscape tradition of northern Europe and the US, respectively. In the reverential gaze, the implied line of sight moves up, whereas, in the magisterial gaze, the line of sight moves down. Boime reads these visual tropes to index different ideological formations. For more, see Albert Boime, The Magisterial Gaze: Manifest Destiny and American Landscape Painting 1830–1865 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 20–23. ↩

- Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1977), 128–135.“Structure of feeling” comes from Raymond Williams to describe an inchoate and pre-semantic formation. ↩

- My argument aligns with others in Asian-American studies that have noted the role that discourses about Asia and Asian-Americans play in mid-century US visions of an integrated Pacific world. Colleen Lye, America’s Asia: Racial Form and American Literature, 1893–1945 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005) and Christine Hong, “Illustrating the Postwar Peace: Miné Okubo, the ‘Citizen-Subject’ of Japan, and Fortune Magazine,” American Quarterly 67, no. 1 (March 2015): 105–140. ↩

- Racial liberalism describes an official US anti-racist discourse and ideology that became dominant in the middle of the twentieth century. Under a racial liberal view, racism is fundamentally understood as a psychological and moral issue of white prejudice deracinated from the history and organization of social, political, and economic life in the US. Its cultural and political ascendency was keenly tied to the global political and economic dominance of the US after WWII. Jodi Melamed, Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism. (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). ↩

- For a comparative analysis of US and Japanese imperial formations in the Pacific during World War II, see Takashi Fujitani, Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War II (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2011). ↩

- Daniel Immerwahr, “How the US has Hidden its Empire,” The Guardian, February 15, 2019. ↩

- For a brilliant theorization of the way that the national incorporation of Japanese Americans draw them into the project of native erasure, see Jodi Byrd, “Killing States: Removals, Other Americans, and the ‘Pale Promise of Democracy,’” in Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism, (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 185–220. For an account of the Leupp Isolation Center, see Lynne Horiuchi, “Spatial Jurisdiction, Historical Topographies, and Sovereignty at the Leupp Isolation Center,” Amerasia 42, no. 1 (2016): 82–101. For an account of the Gila River Indian Community, see Karen J. Leong and Myla Vicenti Carpio, “Carceral Subjugations: Gila River Indian Community and Incarceration of Japanese Americans on Its Lands,” Amerasia 42, no. 1 (2016): 103–120. ↩

- Goldstein, Formations, 14. ↩

- Goldstein, Formations, 15. ↩

- Goldstein, Formations, 16. ↩

- Goldstein, Formations, 16. ↩

- Goldstein, Formations, 16. ↩

- For an extended account on African American’s view of Japan and China during World War II, see George Lipsitz, “‘Frantic to Join . . . the Japanese Army’: Black Soldiers and Civilians Confront the Asia-Pacific War,” in Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific War(s), ed. Takashi Fujitani, Geoffrey White, and Lisa Yoneyama (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 347–377. ↩

- Jasmine Alinder, Moving Images: Photography and the Japanese American Incarceration (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009). ↩

- See Linda Gordon and Gary Okihiro, eds., Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008). ↩

- W. J. T. Mitchell, “Imperial Landscape,” in Landscape and Power, 2nd Edition, ed. W. J. T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2002), 14. ↩

- Mitchell, “Imperial Landscape,” 14. ↩

- Mitchell, “Imperial Landscape,” 17. ↩

- Yet, as Day notes, such logics rests on a triangular relation of Native, Settler, and Alien positionality. For a fuller elaboration, see Iyko Day, Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 73–114. ↩

- Boime, The Magisterial Gaze, 21. ↩

- Boime, The Magisterial Gaze, 5. At this point, Boime’s argument on the deep ideological linkage between US landscape and (settler) colonial practice is uncontroversial. Indeed, textbook accounts of US landscape paintings regularly point to their connection with the manifest destiny of the frontier. Yet, accounts of the US imperial landscape have rarely move beyond the nineteenth century. In large part, this truncated history has to do with the decline in landscape painting. Landscape, however, did not disappear from US visual culture in the twentieth century. Rather, as Mitchell notes, the rise of modernism displaced landscape from its central position in fine art, but its conventions penetrated mass visual culture to such an extent that landscape achieved the status of visual common sense. Landscape hence became ubiquitous, the ephemera of mass visual culture like advertisements, postcards, and amateur art. In this article, part of my aim is to extend this history into the twentieth century. ↩

- Alinder, Moving Images, 45–52. ↩

- Alinder also finds a pioneer subtext to Born Free. However, she reads it as way of framing the post-interment dispersal of Japanese American to the East. For such a reading, see Alinder, Moving Images, 64–66. ↩

- Elena Tajima Creef, Imaging Japanese America: The Visual Construction of Citizenship, Nation, and the Body (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 36. ↩

- Creef, Imaging Japanese America, 36. ↩

- Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” in Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner: “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” and Other Essays, ed. John Mack Faragher (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 33. ↩

- See Creef, Imaging Japanese America, 13–70. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 7–9. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 7–9. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 3. ↩

- Thy Phu, “The Spaces of Human Confinement: Manzanar Photography and Landscape Ideology,” Journal of Asian American Studies 11, no. 3 (October 2008), 337–371. ↩

- Alinder, Moving Images, 46. In this sense, Born Free is less a break from Adams’s longstanding concern over natural aesthetic than an opportunity to put this concern into social and political practice. ↩

- In this way, Born Free offers a useful counterpoint to Day’s analysis of the landscape photography of Jin-me Yoon and Tseng Kwong Chi. For Day, Yoon’s and Chi’s landscape photography disidentifies with masculine white settler colonial personifications of land by parodying its visual convention as the backdrop to the “asiatic body.” Born Free, on the other hand, illustrates how such a technique does not guarantee critique. Indeed, Born Free sets the asiatic body in nature in order to incorporate people of Japanese descent into the project of US colonialism. ↩

- For an account on the anti-Japanese racist visual culture at the time, see Creef, Imaging Japanese America; Linda Gordon and Gary Okihiro, introduction to Impounded, 1–10; Alinder, Moving Images, 52–55; and Katherine Stanutz, “Inscrutable Grief: Memorializing Japanese American Internment in Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660,” American Studies 56, no. 3 (2018): 47–68. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 23; 30; 59. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 112. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 112. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 112. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 112. ↩

- Phu, “The Spaces of Human Confinement,” 355. ↩

- Deborah Bright, “The Machine in the Garden Revisited: American Environmentalism and Photographic Aesthetics,” Art Journal (Summer 1992): 62. ↩

- Bright, “The Machine in the Garden Revisited,” 62. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 9. ↩

- Middle-class whiteness has long characterized notions of pristine nature in general and mountains in particular in US racial imaginaries. For a more general account on the relation of whiteness and mountains, see Richard Dyer, White: Essays on Race and Culture (London: Routledge, 1997). For an account on the US relation of middle-class whiteness and landscape, see Martin A Berger, Sight Unseen: Whiteness and American Visual Culture (Berkeley: University of California, 2005); Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California, 2016). ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 26–26; 82–83. ↩

- Phu, “The Spaces of Human Confinement,” 334. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 25–29. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 25. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 29. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 25. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 104. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 22. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 111. ↩

- Alinder, Moving Images, 71. ↩

- Adams, Born Free and Equal, 6. ↩