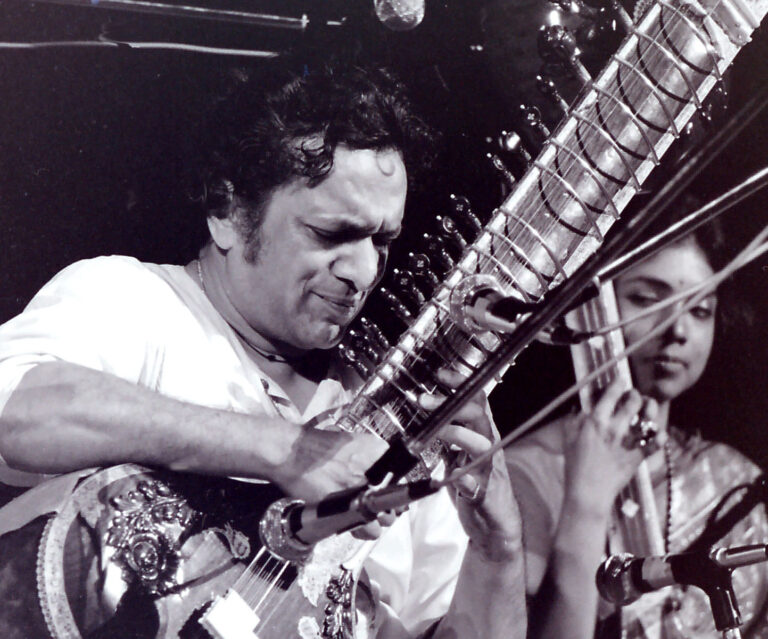

When Pandit Ravi Shankar began performing for Western audiences in the 1960s, his collaborative instinct for the meeting of Hindustani music and jazz was challenged by what he described as “shrieking, shouting, smoking, masturbating, and copulating” audiences of “strange young weirdos,” according to Mick Brown writing for The Telegraph. We can only imagine the debates of high and low art which were fought between Shankar and George Harrison, Bud Shank, or even Tony Scott, who were few of his many collaborators from the West. Caught between its original referent and its appeal to learned style, jazz (with its roots in African-American history) is placed at the center of debates about authenticity, gatekeeping, and located-ness. Once something like “world music,” composed through collaboration, fusion, and re-sampling, enters a space not used to any of the styles mixed into this world of music, it creates unique soundscapes. Ethnomusicologist Martin Stokes, writing “On Musical Cosmopolitanism,” looks at the course of sounds through the world to think of music “as a process in the making of ‘worlds,’ rather than a passive reaction to global ‘systems'” (6). The world created is never an unproblematically imported ambience. A jazz club anywhere in the world does not always correspond to Dixieland, or Chicago, or New York, nor does it reveal the influence of Black labor-songs, vaudeville, or ragtime. This is where an album like Indian composer duo Shankar-Jaikishan’s Raga-Jazz Style (1968) becomes interesting, compressing 11 ragas from Hindustani music into curt pieces corresponding to different, morphed forms of jazz. By looking at the history of the circulation of interfused styles of jazz in America, Goa, Bombay, and mainstream Hindi cinema, this paper examines the material conditions of creativity, and attempts to inscribe this global creative collaboration of forms into a connected history of jazz and Hindustani music.