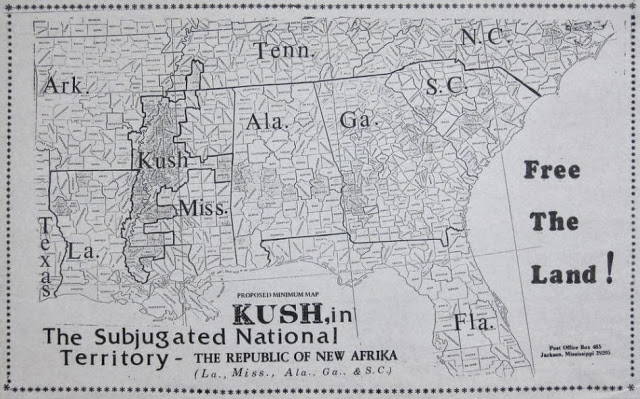

In 1968, the world was changing. New nation-states were forming as former colonies revised relationships between Africa, Asia, and the “West.” Some fought hard for their liberation, and some were still fighting. From Vietnam to Zimbabwe, bloody struggles against racist settlers and western capital clarified the tenacity of white supremacy and imperialism. Other nations were “peacefully” exchanging white political leadership for parties and personalities rooted in local soil. All excited the US Black left who welcomed the changes as the ideal condition for Black liberation. Among them were activists who, beginning in March 1968, decided to pursue the creation of an independent Black nation-state that would occupy land in the Deep South. Considering Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, and Georgia as the rightful territory of their Republic of New Afrika, those who championed independence sought to replicate the apparent successes of Tanzania and other newly formed states, while contributing to the complete overthrow of western hegemony. This contribution explores the theory of the New Afrikan struggle for land and independence. It considers how New Afrikans negotiated their African ancestry and colonized status with their distinctly North American position within geopolitics. In asserting their right to self-determination, New Afrikans complicated the meanings of captivity and Third World solidarity in ways unique to the Black Power era. Even as they built on their predecessors from the African Blood Brotherhood, UNIA, and even the CPUSA, New Afrikans helped to frame their era’s political ideas in a manner that continues to guide projects of international liberation and solidarity.