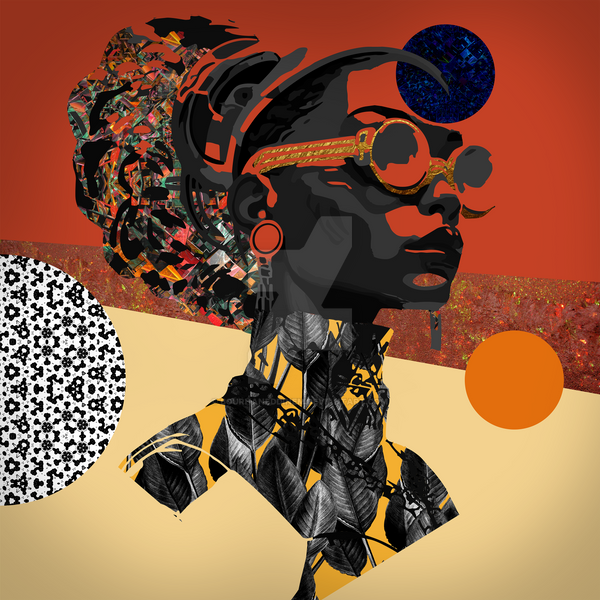

Black popular culture draws on everyday Black experiences to create ideas of futurity. There are well known examples of Afrofuturism, such as the Black Panther films, as well as the music of George Clinton, Sun Ra, Janelle Monáe, and Erykah Badu, which offer profound versions of Black futures. In addition to these essential examples, some artists are not always explicitly named as such and incorporate robust conceptions of futurity and speculation into their work. This article examines the performances of Missy Elliott, Megan Thee Stallion, and Cedric the Entertainer. It argues that through their embodied performance practices that cite Black life, they create persuasive critiques of the present and move forward ideas about the future. In addition to using futuristic settings and themes, their embodiments work to put forth compelling ideas of speculation. These artists employ notions of the posthuman, a speculative figure that interrogates the category of the human through embodied gestures, dances, and other movement styles. The examined performances challenge notions of respectability established through white norms and neoliberal disciplinary mechanisms that police and harm Black bodies and render them outside of humanness. Specifically, Missy, Cedric, and Megan’s performances are rooted in concepts like ghetto, ratchet, and hood, which push back against US society’s notions of the human as defined through the respectable laboring body that is also read through the standard of whiteness. The twin dynamic of the human and posthuman provide critiques of the historic and layered expansiveness of anti-blackness while also centering Black people’s joy, pleasure, desire, and freedom. As such, these performances proffer notions of the present and future, the human and the posthuman. The force and effectiveness of these artists’ performances reside in how they draw from the everyday ways Black people articulate ideas of radical futurity.

Keyword: performance studies

Introduction

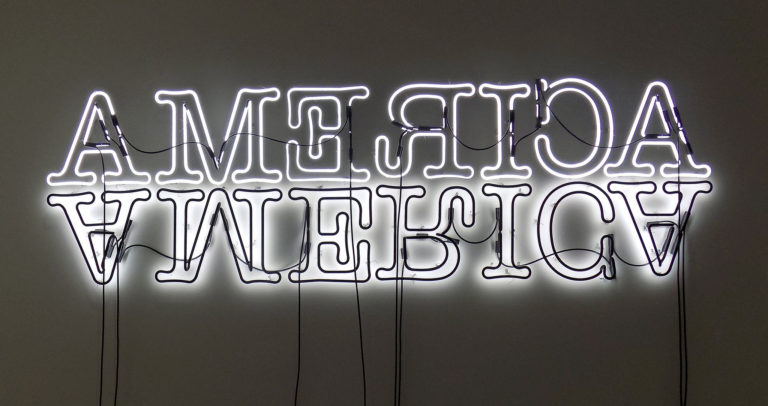

Gwyneth Shanks discusses the scope of Not a Trump Issue, which privileges resistant actions that are never reducible to nor fully concerned with the Trump Administration’s policies and actions. In the wake of the Administration’s tacit and overt support of white supremacist and sexist ideologies, deregulation, global climate change denial, and attempts at voter suppression and the criminalization of communities of color, “Not a Trump Issue” questions how radical, anti-racist, feminist scholars, artists, activists, and educators can enunciate their own forms of resistance. The issue privileges actions that are engaged with surfacing deeper historical structures of inequity or dispossession; the issues at stake for the authors in “Not a Trump Issue” is not not Trump nor our political present, but always already our collective pasts.