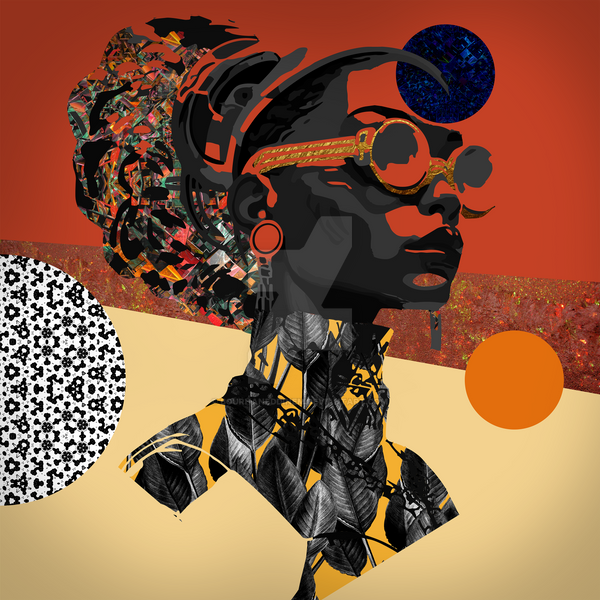

Black popular culture draws on everyday Black experiences to create ideas of futurity. There are well known examples of Afrofuturism, such as the Black Panther films, as well as the music of George Clinton, Sun Ra, Janelle Monáe, and Erykah Badu, which offer profound versions of Black futures. In addition to these essential examples, some artists are not always explicitly named as such and incorporate robust conceptions of futurity and speculation into their work. This article examines the performances of Missy Elliott, Megan Thee Stallion, and Cedric the Entertainer. It argues that through their embodied performance practices that cite Black life, they create persuasive critiques of the present and move forward ideas about the future. In addition to using futuristic settings and themes, their embodiments work to put forth compelling ideas of speculation. These artists employ notions of the posthuman, a speculative figure that interrogates the category of the human through embodied gestures, dances, and other movement styles. The examined performances challenge notions of respectability established through white norms and neoliberal disciplinary mechanisms that police and harm Black bodies and render them outside of humanness. Specifically, Missy, Cedric, and Megan’s performances are rooted in concepts like ghetto, ratchet, and hood, which push back against US society’s notions of the human as defined through the respectable laboring body that is also read through the standard of whiteness. The twin dynamic of the human and posthuman provide critiques of the historic and layered expansiveness of anti-blackness while also centering Black people’s joy, pleasure, desire, and freedom. As such, these performances proffer notions of the present and future, the human and the posthuman. The force and effectiveness of these artists’ performances reside in how they draw from the everyday ways Black people articulate ideas of radical futurity.

Keyword: popular culture

Cannaboom: Race and Labor in California Cannabis Cultures

Encouraged by state requirements for prepackaging, Black and Latinx producers and distributors of legal cannabis in California have developed novel, symbolically and socially significant forms of marketing. Black and Latinx cannabis industries have developed their own “commodity aesthetics,” using product packaging, live events, and social media to entice buyers with a combination of beautiful sights, smells, textures, signs, and symbols that represent the contradictions of working-class Black and Latinx life in contemporary California. Black and Latinx cannabis popular cultures combine images of freedom and transcendence with depictions of the low wage jobs that many Black and Latinx people work. This is because, rather than an impediment to work, cannabis consumption is a kind of support for or accessory to labor. Many consumers use cannabis to dull the tedium and pain of labor and to sustain them throughout the workday. This essay provides a critical overview of Black and Latinx cannabis marketing in California, and its targeting of working-class consumers of color. While I discuss several examples, my central case study is the successful Black and Latinx cannabis distributor Teds Budz. I draw on interviews, ethnographies of live cannabis events, and visual studies of cannabis packages and social media, arguing that seemingly “escapist” qualities in cannabis culture critically foreground the material limits of the world from which Black and Latinx workers are trying to escape. Cannabis commodity aesthetics, I conclude, promise people of color an exit from the drudgery of work that can also tighten their ties to low wage jobs.

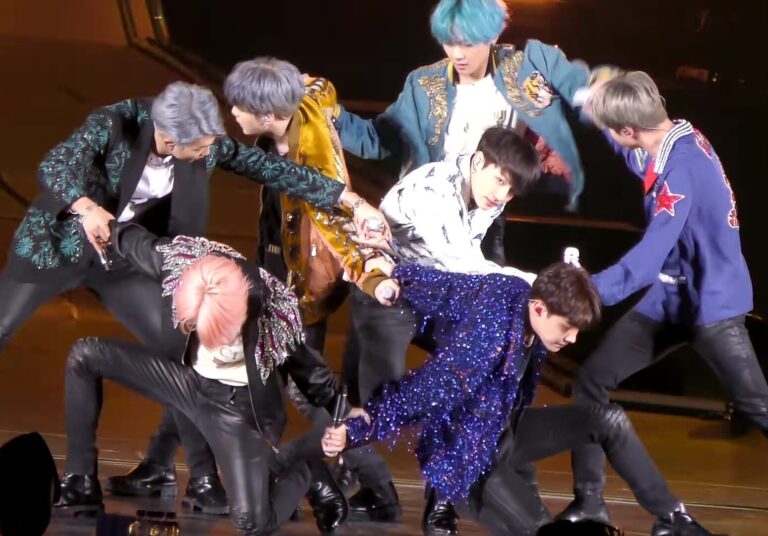

BTS and the Labor of Techno-Orientalism

This article makes the case that the discourse around K-pop supergroup BTS and their fans—known as ARMY—marks an intersection between techno-Orientalism, the abstraction and demonization of Asian labor, and Korea in the US imperial imaginary. BTS exemplifies what I suggest is a contemporary form of Asian racialization that emphasizes the Asian figure as embodying a series of seeming contradictions between the synthetic/mechanistic and the undeveloped/primordial. BTS reveals the ways that these threads of racialization do not contradict but rather complement each other, explaining how narratives marveling at the group’s technical proficiency/synchronicity/productivity can exist side by side with suggestions that their musical output is the result of a labor that is denigrated because it is perceived as being mechanized, abstract, and devoid of the qualities of artistry and creativity exclusively associated with Western modernity.

Surviving and Thriving: Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa Dream Worlds in Animal Crossing New Horizons

As a queer, crip, genderfluid, and diasporic Pilipinx scholar-activist-educator, my ancestors, communities, and I live at the intersections of multiple sites of oppression and resistance. As someone who is sick, disabled, and neurodivergent, I experienced anxiety, depression, and chronic bodymind pain before the pandemic and even more during the pandemic. Nintendo Switch’s Animal Crossing New Horizons (ACNH) video game kept me afloat during uncertain times. ACNH opened up a whole new alternative universe for me to live in. I meditated more when escaping to my scenic and calming virtual island. I relaxed more when fishing, catching butterflies, and hearing the tranquil ocean waves crash within the game. Building my dream world within my ACNH virtual game contributed to me surviving and fostering deeper friendships with fellow sick, disabled, neurodivergent, queer, transgender, Black, Indigenous, and/or people of color (BIPOC) friends. ACNH became a safe way for us to socialize and it continues to be a source of joy for many of us. I highlight how my experiences with ACNH allowed me to cultivate queer, crip, and decolonial Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds where all beings including people, animals, land, water, and air thrive together.