Introduction

My queer, crip, and genderfluid Pilipinx ancestors dreamed of a world where our intertwined communities and I can expand into the endless possibilities of our authentic selves, communities, and worlds of rest, joy, and connection. My ancestors and I are queer, crip, and genderfluid as we actively resist constructed and imposed scripts for living placed on us by society. In this essay, I share how I and many queer, transgender, genderfluid, neurodivergent, chronically ill, disabled BIPOC struggled to survive before the pandemic and during the pandemic. Nintendo Switch’s Animal Crossing New Horizons became a venue for me and my multiply marginalized friends to connect and find routine gentleness and softness within the game when doing our best to survive in a society that continues to disregard multiply marginalized people. As our chronic pain, depression, illnesses, and anxieties intensified, we built comfy and cozy community together in and out of ACNH with our friendships centering consent and social distancing. We engaged in playful and diverse queer and crip neurodivergent communication defying constructed and imposed expectations for compulsory communication. We reveled in queer and crip friendships which defied constructed norms for in-person-only friendships in and out of the game. We met each other’s access needs in the ways we could. Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds were built when we practiced the decolonial Pilipinx Kapwa “Self in the Other” praxis where we rooted ourselves in interdependent connection with all beings on earth in a sustainable manner in and out of the game.1 We dreamed of Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa worlds where all have access to interdependent and sustainable self and community care.

Ancestors, Community, and Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa

Background

Content note: colonial violence and multiple systemic oppressions

Why is the comfy and cozy community found within ACNH critical for multiply marginalized people? I will discuss how my sick, disabled, neurodivergent, queer, transgender, genderfluid, and femme Pilipinx ancestors and communities survived and continue to survive multiple forms of colonial and systemic violence. Cultivating alternative dream worlds of possibility-making and relaxing into our fullest and most authentic selves in Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice interdependent community is what my ancestors dreamed of.

Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa centers how my ancestors and communities continue to resist and dream of alternative worlds where all beings thrive and are fully valued, loved, and taken care of, because as colonized peoples, we do not always have access to dignity and respect. During the late 1800s in the Philippines, my great-grandfather’s family actively protested and resisted Spanish and U.S. colonial violence and thus my mother’s clan was eliminated. My great-grandfather was one of two brothers who survived and who were taken in, hidden, and adopted by another family. My great-grandfather was separated from his brother and told to never to share who he really was and where he came from in order to protect himself. This story of my great-grandparent is one of many rarely written stories of resistance to racist and ableist colonization as colonizers do not consider BIPOC to be intelligent, capable, and worthy of living.

My father’s parents, my grandparents, who raised me and my siblings, survived WWII in the Philippines. Their Lucban village was burned down by Japan’s imperial soldiers, and they were forced to hide and live in the forest. My grandma gave birth to my uncle in the forest without a medical doctor and without medical care. In order to survive and with false promises of a path to U.S. citizenship, my grandfather fought alongside U.S. soldiers. What my grandparents went through is one of a multitude of rarely documented stories of BIPOC who continue to resist state-sanctioned imperialist violence.

Growing up in the Philippines, my parents experienced ongoing colonization and imperialist U.S. military occupation of the Philippines along with the dictatorship of the Marcos regime. The Philippines and its more than 182 Indigenous tribes continue to experience systemic poverty and destruction of Indigenous peoples’ bodyminds, waters, air, and lands due to colonization, imperial wars, and neoliberal profit-over-people mentalities and actions found throughout education, healthcare, leadership, and work systems. My parents thus immigrated to the United States searching for dreams of freedom and a better life, yet only to be met with broken dreams of systemic discrimination, hostility, poverty, and anti-Asian violence. The stories of my immigrant parents are one of the many rarely widely-shared stories of Asian immigrants within the US.

Fast forward to today, I am a freshly minted Ph.D. and higher education Queer Crip Pilipinx scholar-activist-educator. It was not an easy journey for me to survive yesterday, survive today, and survive tomorrow. It was difficult for me to graduate with my doctorate degree as a queer, genderfluid, neurodivergent, and chronically ill disabled person of color as I am not supposed to be here today living my fullest and authentic self with interconnected communities who are naming and challenging multiple interconnected systems of oppression. Our collective communities are not supposed to be here today. Yet, we, as a collective of survivors and dreamers, are resisting, surviving, and thriving.

As a scholar-activist-educator, I practice Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa of interdependent and sustainable communities fostered within my teaching and activism because the systems I navigate and survive everyday were never meant for me and my multiple interconnected communities as they were built to erase and minimize us. I align Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa with the tenets of Indigenous land- and culture-back decolonization as interdependent and sustainable communities challenge the built-in and ongoing systems and structures of colonization found throughout every aspect of our society as shared by Indigenous scholar, J. Kēhaulani Kauanui.2 Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa dreams the disability justice tenet of interdependence brought forth by Patty Berne, Aurora Levins Morales, and Sins Invalid (2018) into fruition as all beings are interconnected and need each other to survive.3 Following the wisdom and leadership of Indigenous and two-spirit scholars such as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa honors how the liberation of all people is bound with the liberation of BIPOC peoples, water, air, and land.4 As Black feminists Aph Ko and Syl Ko share, the freedom of all beings is needed including honoring the freedom of BIPOC peoples and animals as interconnected.5 Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa is decolonial, queer, and crip, as it resists constructions of who is worthy of life, dignity, and respect as all of us, especially those multiply marginalized and impacted directly by systems of oppression, deserve access to quality and sustainable care, community, rest, and joy.

Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa and Youth Learning through Youth Popular Culture Animated Storytelling

Youth learning and youth popular culture are spaces where Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds are needed and, simultaneously, where they manifest. As children, my siblings and I were inevitably exposed to historical and systemic anti-Asian violence when learning of and witnessing Pilipinx ongoing histories of oppression and resistance. My family grew up in a low-income, majority BIPOC, and highly policed neighborhood where BIPOC were criminalized and pitted against each other. Our house was robbed, trashed, and vandalized multiple times. Anti-Asian slurs were yelled at us at our school and neighborhood. My siblings and I knew what systemic racism, classism, and ableism were and we knew the divisions constructed between our interconnected communities as we experienced them, lived them, and felt them before we learned textbook definitions of systemic interconnected oppressions. My mom, who worked two low-wage jobs, shared with me how her supervisor and coworkers treated her as less intelligent, less capable, and less worthy. My dad worked multiple low-wage jobs and struggled to maintain employment before becoming disabled. The racism and ableism my family and I experienced during my youth was not an individual occurrence; it was systemic—built into the fabrics of our societal systems.

It was not until college that I learned I come from a lineage of Pilipinx people in which women, transgender, genderfluid, and queer people led communities who actively resisted colonization and who continue to resist colonization, imperialism, and neoliberalism today.6 It was not until later during college, at student of color conferences, when I learned how violence and trauma from historical and ongoing oppressions lead to the physical, health, and mental health illnesses and disabilities found within myself, my family, and greater diasporic Pilipinx communities today.7 Settler colonization brought forth systemic cis-hetero-sexist-racist-ableism that me, my family, my ancestors, and my interconnected communities continue to resist.

My writing, research, and activism showcase how youth learning and youth popular culture spaces can serve as venues where we refuse oppressions placed upon our multiple communities and where we dream decolonial, queer, crip, and disability justice worlds of infinite possibilities. What if youth learned about the fullness and richness of our distinct, yet shared, histories of collective resistance? What if youth learned directly from the dreams and wisdom of sick, disabled, neurodivergent, queer, nonbinary, and transgender BIPOC communities? What if every single being on earth including our animal, water, air, land, earth, and plant siblings had access to abundant care, rest, joy, dignity, respect, and community?

Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa through ACNH

As I struggled to survive before the pandemic and during the pandemic, I found the youth learning and youth popular culture world of ACNH to be a place where I found myself resisting multiple oppressions and dreaming themes of a world my ancestors and communities long for: a world of routine gentleness and softness; a world of comfy and cozy community; a world of queer and crip friendships; a world of playfulness of communication; a world of interdependent and interconnected relaxation. These themes found within ACNH showcase Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa worlds where we thrive in decolonial, queer, crip, and disability justice interdependent connection and sustainable community.

Routine Gentleness and Softness

The cis-hetero-sexist-racist-ableist world settler colonization brought forward is neoliberal as it prioritizes profit over people, individual achievement, private wealth accumulation, and disconnection over community wealth and relationship-building to transform systems. Before the pandemic and especially during the start of the pandemic, I experienced major depression, anxiety, PTSD, and OCD which aggravated my autoimmune illness, chronic bodymind pain, and other health disabilities. It was a struggle to get out of bed, remember to take medications, connect, and maintain spoons to feel hopeful enough to get through the day to tomorrow. I felt overwhelming sorrow and despair, and I was disconnected from myself and from those around me.

Fortunately, a loved one shared ACNH with me. During this difficult time, ACNH allowed me to experience the bountiful possibilities of Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds of interdependent and sustainable community found within the youth learning and youth popular culture animated storytelling realm of ACNH. At this very moment, time, and place, ACNH was the joy and playfulness in community connection I was yearning for. I thrived in the routine softness and gentleness found with animal ACNH friends within the game and with friends in real life playing the game. Routine softness and gentleness aligns with Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds of interdependent and sustainable community as it is the settling in and expanding into co-created routines which invite ease into our lives as we share our authentic selves in relation with others. ACNH became an alternative universe for me and many chronically ill, neurodivergent, depressed, anxious, and disabled friends to connect in virtual and real worlds of interdependence and sustainable community care during a time of increasing disconnection and despair.

Routine gentleness and softness within ACNH includes animal ACNH friends checking in with us every day. They share, “What’s up? I miss you. Have you eaten a good meal lately? What are your favorite foods? What are your favorite hobbies? Do you like green, oolong, or black tea?” Checking in and showing up for each other in the ways we can is a way we can cultivate queer and crip sustainable worlds which refuse society’s individual productivity mandates which lead to disconnection and isolation. Friend check-ins during turbulent times mean everything, especially when they are check-ins from adorable frog, deer, and elephant ACNH friends. In addition to animal ACNH friends, my friends in real life checked in on me and asked, “How are you feeling? Need anything today? Want to visit my island today? Need any fruits, bells, and other items?” Friends in real life checking in on each other and asking if we need anything in real life and in the game is queer and crip resistance as our world encourages individualism and isolation over community connection and collective care. My animal ACNH friends, friends in real life, and I cultivated routine gentleness and softness with each other, encouraging each other to eat, drink water, enjoy tea and coffee, rest, and play during a time of growing uncertainties. We swapped homemade banana bread, honey cake, chocolate chip cookies, brownies, sourdough bread, fruit tarts, apple crisps, Hawaiian chocolates, and more both in real life and within the game.

Routine softness and gentleness in the game includes animal ACNH friends sharing their love for fishing, catching bugs and butterflies, museum-going, boat-riding, digging for treasures on the beach, and visiting local shops. They expressed excitement over sharing space with other animal ACNH friends and friends in real life visiting within the game. This routine gentleness and softness of everyday joyful connections and community experiences disappeared during the pandemic. It became even more stressful to visit beaches, museums, and local shops. Enjoying slices of life experiences within the game during a time when our everyday routines halted was life-giving and a breath of fresh air.

Routine gentleness and softness found within ACNH supported my chronically ill, neurodivergent, and disabled self as I was able to have more routine and structure in my life through the game. As a neurodivergent person, I depend upon routines which assist me in surviving and thriving every day. Since the pandemic disrupted my daily routines, it was refreshing to find routine expectations and structures of gentleness and softness within ACNH. I enjoyed designing my island in a routine, orderly, and artistically pleasing fashion as I aligned my apple, orange, peach, and cherry trees to form bountiful fruit orchards in a recurring pattern. I cherished the routine of changing seasons and the structured expectations of holidays and celebrations within the game.

Routine gentleness and softness found through community wealth was promoted throughout the game as anyone can shake trees for bell currency within the game. ACNH animals and I shared gifts daily which satisfies my neurodivergent desire to express my appreciation of friends through gift giving. This dream world of community wealth centered within the game supports Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice interdependent and sustainable communities of care as we have been taught individualism, scarcity, and fear thinking to be the expected way of being. Within ACNH, we live in a world of routine gentleness and softness where community wealth is the norm. My Pilipinx ancestors and interconnected communities support gift giving as a form of community wealth and care. Sharing our fish, butterflies, bugs, art, fashion, homes, and gardens with each other in the game allowed us to manifest Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice dream worlds of routine softness and gentleness where we share, play, and rest together in interdependent and sustainable communities of care settling in and expanding into our authentic selves in relationship with each other.

Comfy and Cozy Community

During pandemic times, ACNH supported a comfy and cozy community. Comfy and cozy communities grant us unlimited permission to rest, to settle in, and to expand into our authentic selves in relation to others near and far. Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice interdependent and sustainable communities of care and connection is found within comfy and cozy cultures. I often do my best to support and foster comfy and cozy cultures within my life, friendships, activisms, and teaching since our settler colonial cis-hetero-sexist-racist-ableist and neoliberal world promotes fast-paced living, productivity, stress, and feelings of inadequacy. A comfy and cozy community fostered within ACNH allowed me and my animal ACNH friends and friends in real life to relax and settle into our unapologetic neurodivergent, chronically ill, disabled, transgender, non-binary, queer, femme, and BIPOC selves in community with others. We reveled in sharing our love for our special interests together, comfy and cozy, often while wearing our pajamas lounging on our sofas and beds. Queer, crip, and femme of color disability justice activists such as Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha center how sofas and beds are worlds as they cultivate crip dreams for futures which grant people boundless access to quality basic needs of rest and community connection where all access needs are prioritized and met.8

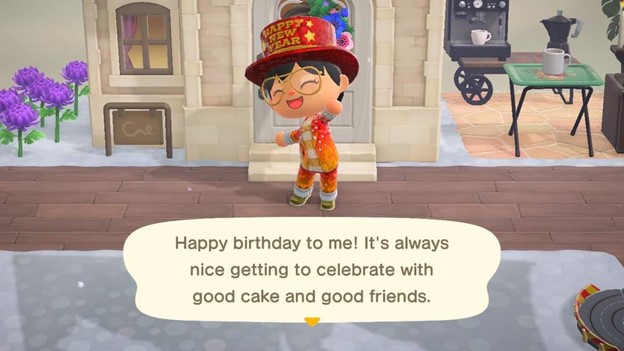

Comfy and cozy community took place when my animal ACNH friends and friends in real life celebrated our birthdays together within the game and in real life. Birthdays can be lonely and a time when anti-disabled, anti-transgender, anti-queer, and other traumatic memories of unsupportive family and friends can resurface. Celebrating birthdays with supportive chosen family and friends both within ACNH and in the real world can cultivate new comfy and cozy rituals of appreciation and joy for our multiply marginalized communities who are often not granted respect and dignity in society. ACNH became a space where my multiply marginalized communities and I can celebrate our existence and friendship with ease. With ACNH, I am never alone or forgotten on my birthday when my animal ACNH friends surprise me with a birthday party, cupcakes, and a pinata. In addition to the game, friends in real life shared strawberry cupcakes, veggie lumpia, veggie pancit, and gifts in a socially distanced manner. ACNH created a space for us to laugh and enjoy a comfy and cozy community where we expressed gratitude and bliss over the creativity of our decolonial and disability justice islands of interdependence. We shared our neurodivergent special interests centering our expansive love for Studio Ghibli, Hello Kitty, Pokémon, anime, and animated storytelling. Comfy and cozy community granted us permission, time, and space to relax within the game and in real life, in virtual and socially distanced community.

Queer and Crip Friendships

Queer critical race feminists such as Karma Chávez share how play is queer when we live in a world that does not invite us to play and connect with each other in deeply intimate ways so that we may collaborate together to challenge and transform systems.9 Queer crip of color feminists such as Shayda Kafai share with us how queer and crip play found within crip kinships, crip friendships, crip intimacies, and crip centric liberated zones is resistance when our society does not center and validate the vast and immeasurable community building of multiply marginalized disabled people.10 According to queer and two-spirit Indigenous scholars, queer actively refuses colonial norms of constructed binaries and expectations breaking down the walls built between communities.11 Queer of color scholars center how queer movements create alliances, friendships, and coalitions with those who resist oppressive systems of living.12

Queer crip of color feminist critiques from Sami Schalk and Jina Kim further connect queer, feminist, and crip of color communities together who challenge harmful status quo systems used to divide our communities and instead prioritizes multi-issue movements which actively links communities and issues together as inseparable.13 Disabled and queer Asian American scholars such as Mimi Khúc names the systemic unwellness of our lives operating in built to be broken education and societal systems and institutions.14 Access intimacy brought forth by Mia Mingus centers the urgency for our access needs to be intimately known and met through our active listening, education, and cultivating of care with chosen family and friends.15 My multiply marginalized friends and I found queer and crip play to support access intimacy friendships within and outside of ACNH. My animal ACNH friends and friends in real life cultivated accessible and crip kinship friendships where we were patient and playful with each other ensuring our access needs were and continue to be met.

In and out of the game, our community of friends practiced routine gentleness and softness when we paused and slowed down when one was not feeling well. We understood when one couldn’t communicate that day or for days to months. We asked how we can support each other in the ways we can. We called each other nicknames of fondness to promote neurodivergent camaraderie of reveling in the intricacies of the brilliance of creating words which match ourselves and our feelings best. Since I asked my animal ACNH friends to call me Pikachu and Scorbunny as they are my favorite Pokémon, I invited my friends in real life to call me nicknames of endearment as well. Animal ACNH friends called me Anak as it means child in Pilipinx Tagalog, a term of love. Queer and crip friendships fostered in and out of ACNH showcase Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice worlds of interdependence, crip kinship, and access intimacy which actively protest and refuse worlds and systems of productivity, isolation, and disconnection.

Playfulness of Communication

Crip kinship and friendship took place within ACNH and in real life when animal ACNH friends and friends in real life engaged in playful and accessible communication including non-verbal, kinesthetic, visual, and artistic communication in a socially distanced manner revolving around our special interests. Neurodivergent leaders of color center the critical need for neurodivergent people to access multiple forms of communication access and moments and spaces of rest in order to minimize sensory overload.16 Non-verbal communication access is encouraged in and out of the game as we chatted with each other through the text feature of the game and through text messaging and social media chats on our phones and laptops. We did our best to foster neurodivergent-friendly environments which minimized meltdowns. We turned down the volume and brightness of our game if needed. We lay down and covered ourselves in comfy and cozy blankets. We rested. We created islands friendly to our neurodivergent needs of playful communication and filled with creative themes related to our special interests. Playful communication is intertwined with visual and artistic communication as we witnessed the creativity of each other’s islands without needing to talk out loud or type chat in the game.

Friends in real life visited each other’s islands and drew art on each other’s bulletin boards to communicate with each other in a playful, creative, and artistic fashion. We shared our art worlds of forests, seashores, and ocean views. Crip kinship and friendship supports accessible and playful communication in a socially distanced and consent-based manner, depending on if we have enough spoons that day to engage in interactive community together. Our friendships are not forced, with clear boundaries shared if we have time and energy to play or chat that day. Crip kinships and friendships unapologetically center our special interests and love for cute and adorable things and experiences without shame, minimization, and erasure. We playfully communicate in a socially distanced manner during uncertain pandemic times. ACNH allowed us to settle into and expand into our authentic selves in relation to our interconnected communities and in alignment with Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice worlds of crip centric liberated zones of sustainable and interdependent community care.

Interconnected and Interdependent Relaxation

ACNH supported relaxation and meditation with interconnected and interdependent communities inside and outside of the game. Ocean waves crashing on our sandy beaches calmed us as uncertainties regarding the pandemic grew. Planting, growing, and caring for our flowers with friends soothed us during unstable times as we connected over our appreciation for the nature-based aesthetics of the game. Interconnectedness and interdependence took place in and out of the game as we checked in and played together. ACNH became a reflection of what our multiply marginalized communities crave for in this world: Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice dream worlds of interconnected, interdependent, and sustainable communities of care.

Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa in Youth Learning and Popular Culture

Queer and chronically ill BIPOC feminists such as Audre Lorde imagined dream worlds where marginalized people can rest, settle, and feel at home with their authentic selves and chronically ill and queer bodies.17 For example, Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa dreamed of internally imagined and externally realized worlds where interconnected communities break down constructed borders built between us.18 ACNH is an inwardly imagined and outwardly manifested dream world where queer, crip, neurodivergent, chronically ill, disabled, and BIPOC people in relation to animal, plant, earth, water, and air beings thrive. It is a Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa decolonial and disability justice world of queer and crip rest and joy with sustainable communities of interdependent care and connection.

Those of us who live at the margins of society seek a world where gentleness and softness is routine, a world where we relax into our authentic selves in comfy and cozy community, a world of neurodivergent, queer, and crip friendships, a world of interconnectedness and interdependence, relaxation and meditation, where we thrive in moments of rest and joy. Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds are what my ancestors, communities, and I long for past, present, and future. Our society has much to learn from the leadership and wisdom of youth learning and youth popular culture animated storytelling as they are portals to community building and learning together. These Queer Crip Pilipinx Kapwa dream worlds of interdependence and sustainable communities of care bring us back to Ngọc Loan Trần’s call for our multiply marginalized communities to call each other in.19 It is critical for all people to build collective systems and sustainable worlds of care where beings are called in, cared for, and not pushed out. Disabled and queer BIPOC scholars, healers, and activists such as Aurora Levins Morales remind us how our interconnected and interdependent communities continue to engage in multi-issue movements locally and globally as we dream and manifest healing and liberation together.20 Our inseparable, interconnected, and interdependent communities need each other for our survival and for thriving in our collective dreaming, care, rest, and joy together.

Notes

- Katrin De Guia, Kapwa: The Self in the Other: Worldviews and Lifestyles of Filipino Culture Bearers (Pasig City, PH: Anvil, 2005). ↩

- J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, “A Structure, Not an Event”: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity,” Lateral 5, no. 1 (Spring 2016): https://doi.org/10.25158/L5.1.7. ↩

- Patty Berne, Aurora Levins Morales, and Sins Invalid, “Ten Principals of Disability Justice,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 46, no. 1 (2018): 227–230, https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2018.0003. ↩

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩

- Aph Ko and Syl Ko, Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters (Brooklyn, NY: Lantern Books, 2017). ↩

- Leny Strobel, Babaylan: Filipinos and the Call of the Indigenous (Santa Rosa, CA: Center for Babaylan Studies, 2010). ↩

- E. J. R. David, Brown Skin, White Minds: Filipino-/American Postcolonial Psychology (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing Inc., 2013). ↩

- Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018). ↩

- Karma Chávez, Queer Migration Politics: Activist Rhetoric and Coalitional Possibilities (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013). ↩

- Shayda Kafai, Crip Kinship (Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021). ↩

- Qwo-Li Driskill, Chris Finley, Brian Joseph Gilley, and Scott Lauria Morgensen, Queer Indigenous Studies: Critical Interventions in Theory, Politics, and Literature (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2001). ↩

- Cathy Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” in Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology, ed. E. Patrick Johnson and Mae Henderson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 21–51; E. Patrick Johnson and Mae Henderson, eds. Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology; Jose Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009). ↩

- Sami Schalk and Jina Kim, “Integrating Race: Transforming Feminist Disability Studies,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 46, no. 1 (2020): 31–55, https://doi.org/10.1086/709213. ↩

- Mimi Khúc, “Making Mental Health through Open in Emergency: A Journey in Love Letters,” South Atlantic Quarterly 120, no. 2 (2021): 369–388, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8916116 ↩

- Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy: The Missing Link,” Leaving Evidence, May 5, 2011, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link. ↩

- Lydia X. Z. Brown et al., All the Weight of Our Dreams: On Living Racialized Autism (Lincoln, NE: Dragon Bee Press, 2017). ↩

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, rev. ed. (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007). ↩

- Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, 4th ed. (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2015). ↩

- Ngọc Loan Trần, “Calling In: A Less Disposable Way of Holding Each Other Accountable,” Black Girl Dangerous: Amplifying the Voices of Queer and Trans People of Color, 2013, https://www.bgdblog.org/2013/12/calling-less-disposable-way-holding-accountable/. ↩

- Aurora Levins Morales, Kindling: Writings on the Body (Cambridge, MA: Palabrera Press, 2013). ↩